Context and Policy Issues

Alcohol, cannabis, and other substances, [such as stimulants (cocaine, amphetamines), opioids, and sedatives] are among the substances that are the most commonly misused in Canada.1 This misuse can lead to short- and long-term dependence, disability, mental health issues, and social problems.1 At least 20% of alcohol is consumed at a level considered to be high-risk drinking.2,3 The prevalence of cannabis use among the general Canadian population was 12.3% in 2015, and approximately 10% of those who used cannabis developed a cannabis use disorder.4,5 While not necessarily representative of misuse, in 2013, approximately 22.0% of Ontario adults participated in gambling on a weekly basis, with lottery purchase being the most common.6–8 It is estimated that 2.5% of adults in Ontario participate in gambling at a level that is moderately or severely problematic.9

Despite the positive impact that mental health and addiction services can have in reducing problematic substance use and addiction problems, overcrowded programmes, time restraints (i.e. time out of ones day to travel to and participate in treatment), financial barriers, and fear of stigma, are a few of the barriers to accessing traditional face-to-face care, particularly in rural areas. Interventions for the treatment of problematic substance use and gambling usually include psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing (Ml), behavioral self-management (BSM), and personalized normative feedback (PNF).10 E-therapy, using information technology such as internet- and mobile-based interventions to deliver these psychosocial interventions, has been introduced as a treatment option with the hope of improving access to treatment, reducing time constraints, and reducing costs.11,12 In general, these treatment modalities include structured self-help using online written materials, and/or audio/video files for the participant to use without assistance (pure self-help), or with assistance from therapists by phone, video or emails (therapist-guided). Therapist guidance can be synchronous (the therapist and the patient are speaking or interacting in real time), or asynchronous (the communication is not in real time).

As e-therapies have the potential to increase access to care, it is important to understand their effectiveness. This Rapid Response report aims to reviewthe comparative effectiveness of therapist-guided e-therapy interventions versus other options for the treatment of adults with substance use disorders and other addictions.

Research Question

What is the clinical effectiveness of e-therapy for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders and other addictions?

Key Findings

Evidence on e-therapy for the treatment of substance use disorders and other addictions was from a small number of systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Findings consistently showed that therapist-guided e-therapy was superior to no treatment and wait list in reducing alcohol consumption or cannabis use, and the effect was small. Therapist-guided e-therapy was found to be equivalent to no treatment and wait list for patients with gambling addiction. With respect to substances, evidence was limited to the treatment of problematic alcohol and cannabis use and it is therefore unclear if the results generalize to the misuse of other substances. The evidence on gambling was limited to those who participated in online video poker.

Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including Medline via OVID, PsyclNFO via OVID, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials. The search was also limited to English language documents published between Jan 1, 2013 and May 23, 2018.

Rapid Response reports are organized so that the evidence for each research question is presented separately.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2013. Studies that examined e-therapy in general without separating therapist-guided and pure self-help strategies, or studies that examined pure self-help, were excluded. Trials that were included in a reported SR were excluded. Smoking cessation was not included in this review.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included systematic reviews (SR) and clinical trials were critically appraised using the AMSTAR II,13 and Downs and Black14 instruments, respectively. Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

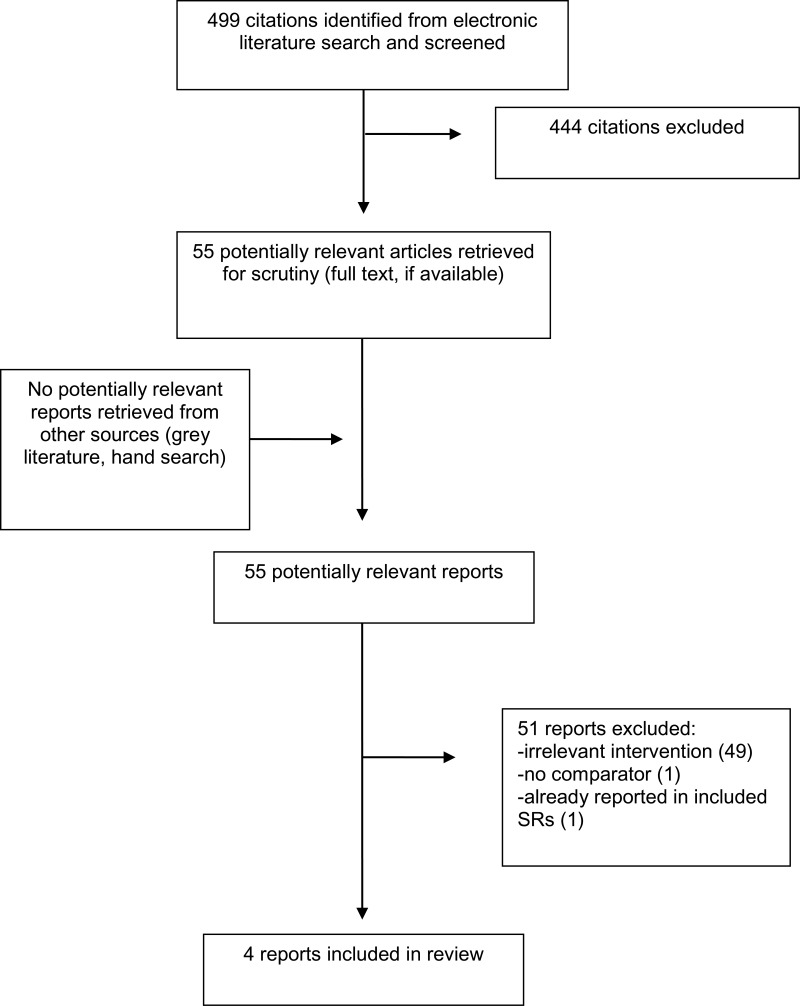

A total of 499 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 444 citations were excluded and 55 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. No potentially relevant publication was retrieved from the grey literature search. Of these potentially relevant articles, 51 publications were excluded for various reasons, while four publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of Study Characteristics

A detailed summary of the included studies is provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Two SRs with meta-analysis15,16 and two clinical trials17,18 were included in the review. One SR performed literature search until 2013 and included four relevant RCTs (total 16 studies),15 one SR performed literature search until 2012 and included four relevant RCTs (total 10 studies); the range of dates of the literature searches were not reported.16 Both included clinical trials are single center, unblinded randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Country of Origin

One SR was performed in the Netherlands, Canada, UK and Germany,15 and one in Australia, the Netherlands, and Germany.16 One RCT was performed in France17 and one in Switzerland.18

Patient Population

One SR included 5,612 adults with high-risk alcohol use,15 and one SR included 4,125 participants of all ages with cannabis addiction or abuse.16 One clinical trial included 1,122 adults with online gambling problems who did not seek treatment,17 and one clinical trial included 308 adults with cannabis addiction.18 No studies involved people with comorbid mental health conditions. None of the included studies examined a military, paramilitary, or veteran population.

Interventions and Comparators

One SR compared e-therapy (web-based interventions based on CBT, Ml, trans-theoretical model of change, and PNF) to no treatment (assessment only, wait list, or alcohol information brochure).15 One SR compared e-therapy (computer and internet-based interventions based on CBT and Ml) to no treatment (assessment only, wait list).16 One RCT compared internet-delivered CBT with therapist guidance to wait list (synchronicity not specified),17 and one RCT compared web-based interventions based on CBT, Mi, and BSM (therapist guidance was synchronous).18

Outcomes

The difference in alcohol consumption after treatment between the two groups was reported on in one SR15 and the difference in cannabis use between the two groups in another SR.16 One clinical trial reported the difference from baseline in gambling severity using Problem Gambling Index Score (PGSI - a reduction in score means lower levels of problem gambling) and attrition rate after 6 weeks of treatment,17 and one clinical trial reported difference from baseline in frequency and quantity of cannabis use and attrition rate after 3 months of treatment.18

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Details of the strengths and limitations of the included studies are summarized in Appendix 3.

The included SRs15,16 provided an a priori design and performed a systematic literature search; procedures for the independent duplicate selection and data extraction of studies were in place, a list of included studies and characteristics were provided, a list of excluded studies was not provided. Quality assessment of the included studies was performed and used in formulating conclusions, and publication bias was assessed in both SRs. Both SRs were based mainly on clinical trials which were heterogeneous with respect to the interventions examined (e.g., components and length of e-therapy, amount and type of therapists support), which may affect the accuracy and reliability of the findings.

The included clinical trials17,18 were RCTs, the hypotheses were clearly described, the method of selection from the source population and representation were described, losses to follow-up were reported, main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings were clearly described, and estimates of random variability and actual probability values were provided. Both trials performed calculations to determine that the trial was powered to detect a clinically important effect. Patients and assessors were not blinded to treatment assignment in both trials which may have impacted the objectivity of the outcomes assessments. Overall, the included studies had good internal validity; their external validity was limited to people with alcohol, cannabis, and non-treatment seeking poker gambling addiction.

Summary of Findings

Details of the findings of the included studies are provided in Appendix 4.

What is the clinical effectiveness of e-therapy for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders and other addictions?

One SR examined the efficacy of internet-delivered interventions for alcohol addiction.15 The difference in alcohol consumption between the e-therapy with therapist guidance and no treatment groups at the post-treatment follow-up was statistically significant (with the e-therapy group having less consumption) and the effect of guided e-therapy was found to be small. The authors concluded that internet-delivered interventions were effective in reducing alcohol consumption and that the effect was small.

One SR16 and one RCT18 examined the efficacy of e-therapy for cannabis addiction. The SR16 found that the difference in cannabis consumption between the e-therapy with therapist guidance and no treatment groups at the post-treatment foiiow-up was statistically significant (with the e-therapy group having lower consumption) and the effect of guided e-therapy was found small. The authors concluded that internet interventions appeared to be effective in reducing cannabis use. The RCT found that guided e-therapy reduced cannabis use on average by one day per week, and the difference was statistically significant, and 23.7% of participants in e-therapy with guidance completed treatment.18 The authors concluded that web-based interventions were an effective alternative to no treatment or wait list.

One RCT examined the efficacy of e-therapy for the treatment of gambling addiction.17 The reduction in PGSI score at post-treatment versus baseline was similar in the guided e-therapy group and the no treatment group. The reduction from baseline was larger in the pure self-help e-therapy than in the group with guidance. However, a limited number of participants completed the post-treatment PGSI; the drop-out rates were 97.3 in the group with guidance and 83% in wait list group. The authors concluded that there was lack of significant difference in efficacy between e-therapy and no treatment, and that guidance could have adversely affected those who had not sought help.

Limitations

Evidence on therapist-guided e-therapy for the treatment of adults with substance use disorders was based on a small number of SRs and RCTs. The accuracy of estimates from SRs was affected by the heterogeneity in the e-therapy treatments, lack of details on the components of e-therapy strategies, and undetermined amount and type of therapist support (e.g., telephone, email). Together with the lack of details on synchronicity of therapist contact in the included SRs, this is a major limitation that affects the precision of the findings. In most studies, the use of a waitlist as a comparator instead of an active treatment comparator might have led to an overestimate of the treatment effect of e-therapy. Since the included studies either did not include or did not perform subgroup analyses based on a military, paramilitary, or veteran population, the generalizability to this population is unclear. Additionally, it is unclear whether the results of the studies generalize to a population using substances other than cannabis or alcohol, as they were the only substances examined in the included studies.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Limited evidence from the included studies showed that therapist-guided e-therapy reduced problematic alcohol consumption or cannabis use, and that the effect was small. Therapist-guided e-therapy was found to be equivalent to no treatment and wait list for patients with gambling addiction, however the drop-out rate was high, and authors concluded that guidance could have adversely affected those who had not sought help. The accuracy of the evidence on the clinical effectiveness of guided e-therapy was affected by the heterogeneity in the e-therapy treatments and lack of consistency in amount and type of therapist support. A narrative review of SRs on problematic alcohol use agreed that more research on the impact of different levels of guidance is needed to clarify its optimal effect.19 In agreement with our findings, Internet interventions in general (without guidance status specification) were also found to have a small but significant effect compared to no treatment in reducing alcohol, opioid, cocaine, amphetamine, and methamphetamine use in various SRs.20,21

While this review did not do an in-depth search or analysis of cost-effectiveness studies, some cost information was identified, and from a healthcare provider perspective, e-therapy plustreatment-as-usual (TAU) with a counsellor’s involvement was found to be likely to be more cost-effective than TAU alone.22 With the threshold for cost-effectiveness generally based on the healthcare budget available, the generalization of these findings to a Canadian context is limited.

The majority of studies on e-therapy for the treatment of substance use disorders examined the efficacy of the intervention in general, they did not separate therapist-guided from pure self-help, and were therefore not included in our review. While it is likely that therapist-guided e-therapy interventions are effective, larger comparative RCTs with consistent reporting would further confirm the clinical effectiveness of therapist guided e-therapies for the treatment of substance use disorders and other addictions.

References

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Aronson

M. Psychosocial treatment of alcohol use disorder. In: Post

TW, editor. UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017

Jun

22 [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from:

www.uptodate.com Subscription required.

- 4.

- 5.

Gorelick

D. Treatment of cannabis use disorder. In: Post

TW, editor. UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2018

Feb

15 [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from:

www.uptodate.com Subscription required.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

Kampman

K. Approach to treatment of stimulant use disorder in adults. In: Post

TW, editor. UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2018

Mar

23 [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from:

www.uptodate.com Subscription required.

- 11.

Cunningham

JA. Addiction and eHealth. Addiction. 2016

Mar;111(3):389–90. [

PubMed: 26860243]

- 12.

- 13.

- 14.

- 15.

Riper

H, Blankers

M, Hadiwijaya

H, Cunningham

J, Clarke

S, Wiers

R, et al. Effectiveness of guided and unguided low-intensity internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e99912. [

PMC free article: PMC4061051] [

PubMed: 24937483]

- 16.

Tait

RJ, Spijkerman

R, Riper

H. Internet and computer based interventions for cannabis use: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013

Dec

1;133(2):295–304. [

PubMed: 23747236]

- 17.

Luquiens

A, Tanguy

ML, Lagadec

M, Benyamina

A, Aubin

HJ, Reynaud

M. The efficacy of three modalities of internet-based psychotherapy for non-treatmentseeking online problem gamblers: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016

Feb

15;18(2):e36. [

PMC free article: PMC4771930] [

PubMed: 26878894]

- 18.

Schaub

MP, Wenger

A, Berg

O, Beck

T, Stark

L, Buehler

E, et al. A web-based selfhelp intervention with and without chat counseling to reduce cannabis use in problematic cannabis users: three-arm randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015

Oct

13;17(10):e232. [

PMC free article: PMC4642392] [

PubMed: 26462848]

- 19.

- 20.

- 21.

Tofighi

B, Nicholson

JM, McNeely

J, Muench

F, Lee

JD. Mobile phone messaging for illicit drug and alcohol dependence: a systematic review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017

Jul;36(4):477–91. [

PubMed: 28474374]

- 22.

Murphy

SM, Campbell

AN, Ghitza

UE, Kyle

TL, Bailey

GL, Nunes

EV, et al. Costeffectiveness of an internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: data from a multisite randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016

Apr

1;161:119–26:-26. [

PMC free article: PMC4792755] [

PubMed: 26880594]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

View in own window

| First author, Year, Country | Objectives

Intervention

Comparators

Literature Search Strategy | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Number of Studies Outcomes |

|---|

| Riper,15 2014, Germany, Netherlands, Canada, Australia | Objectives: “…Internet interventions for curbing adult alcohol misuse have been shown effective. Few meta-analyses have been carried out, however, and they have involved small numbers of studies, lacked indicators of drinking within low risk guidelines, and examined the effectiveness of unguided self-help only. We therefore conducted a more thorough meta-analysis that included both guided and unguided interventions” (p 1)

Intervention: web-based interventions based on CBT, MI, trans-theoretical model of change, and PNF.

Comparators: no treatment (assessment only, wait list or alcohol information brochure)

Literature search strategy: “We conducted literature searches up to September 2013 in the following bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, CINAHL, PUBMED and EMBASE, using key words and text words” (p 2) | “Randomised controlled trials were included that (1) compared a web-based intervention with a control group (in an assessment only, waitlisted or alcohol information brochure control condition); (2) included a low-intensity self-help intervention that the participant could perform on a computer or mobile phone, with or without guidance from a professional; (3) assessed alcohol drinking behaviour in terms of quantity consumed as a primary outcome measure; (4) studied adults aged 18 or older; (5) included alcohol drinkers who exceeded local guidelines for low-risk drinking” (p 2) | Studies not fulfilling exclusion criteria | 16 RCTs (4 RCTs with therapist guidance)

Efficacy:

Effect size of intervention on level of alcohol consumption at post treatment, using AUDIT or FAST score

- -

Therapist-guided - -

Pure self-help (findings not reported in this review)

|

| Tait,16 2013, Australia, Netherlands, Germany | Objectives:“…the aim of this review and meta-analysis was to assemble evidence on the effectiveness of computer and Internet-based interventions in decreasing the frequency of cannabis use and to provide an estimate of the magnitude of that effect” (p 297)

Intervention: computer and internet-based interventions based on CBT, MI

Comparators: no treatment (assessment only, wait list)

Literature search strategy:

“In September, 2012, we searched Medline, PubMed, PsychINFO (1806–2012) and Embase (1980–2012). The search terms were (substance related disorders or addiction, or abuse, or dependence or illicit) and (cannabis or marijuana or marihuana or hashish) and (Internet or web or online or computer or CD ROM) and (prevention or treatment or intervention)” (p 297) | “Studies were included in the metaanalysis if they (1) applied a randomized controlled design, (2) tested the effect of an Internet or computer-delivered intervention (either with or without additional therapeutic guidance) aiming at prevention, indicated prevention or treatment of substance use, (3) reported cannabis use as (one of) the outcome measure(s) and (4) provided usable data to perform the meta-analysis” (p 297) | Studies not fulfilling exclusion criteria | 10 RCTs (4 RCTs with therapist guidance)

Efficacy:

Effect size of intervention on level of cannabis use at post treatment, using different measures of cannabis use.

- -

Therapist-guided - -

Pure self-help (findings not reported in this review)

|

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Identification Test; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; FAST = Fast Alcohol Screening Test; MI = motivational interviewing; PNF = personalized normative feedback; RCT = randomized controlled trial

Table 3Characteristics of Included Clinical Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Year, Country | Study Design Objectives | Intervention Comparators | Patients | Main Study Outcomes |

|---|

| Luquiens,17 2016, France | RCT

“The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of three modalities of Internet-based psychotherapies with or without guidance, compared to a control condition, among problem gamblers who play online poker” (p 1) | Computer-delivered CBT program emailed weekly by a trained psychologist with personalized guidance

No treatment (wait list) | 1122 adults with PGSI score ≥5 who did not seek treatment

- -

301 with e-therapy with guidance - -

264 wait list - -

557 email or CBT book without guidance (findings not reported in this review)

| Efficacy: Difference from baseline in PGSI score at 6 weeks

Attrition rates |

| Schaub,18 2015, Switzerland | RCT

“To test the efficacy of a Web-based self-help intervention with and without chat counseling—Can Reduce—in reducing the cannabis use of problematic cannabis users as an alternative to outpatient treatment services” (p 1) | Web-based self-help intervention, in combination with or without tailored chat counseling, based on CBT, MI, and BSM

No treatment (wait list) | 308 adults

- -

114 e-therapy with guidance - -

93 wait list - -

101 e-therapy without guidance (findings not reported in this review)

| Efficacy: Difference from baseline in frequency and quantity of cannabis use at 3 months

Attrition rates |

BSM = behavioral self-management; CBT = cognitive behaviour therapy; MI = motivational interviewing; PGSI = Problem Gambling Severity Index; RCT = randomized controlled trial

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses using AMSTAR II13

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Riper15 |

|---|

a priori design provided independent studies selection and data extraction procedure in place comprehensive literature search performed list of included studies, studies characteristics provided quality assessment of included studies provided and used in formulating conclusions assessment of publication bias performed conflict of interest stated

|

list of excluded studies not provided heterogeneity across trials in e-therapy programs (content, lengths, amount and types of therapist support)

|

| Tait16 |

|---|

a priori design provided independent studies selection and data extraction procedure in place comprehensive literature search performed list of included studies, studies characteristics provided quality assessment of included studies provided and used in formulating conclusions assessment of publication bias performed conflict of interest stated

|

list of excluded studies not provided heterogeneity across trials in e-therapy programs (content, lengths, amount and types of therapist support)

|

Table 5Strengths and Limitations of Randomized Controlled Trials using Downs and Black14

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Luquiens17 |

|---|

randomized controlled trial hypothesis clearly described method of selection from source population and representation described loss to follow-up reported main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings clearly described estimates of random variability and actual probability values provided power calculation to detect a clinically important effect performed

|

|

| Schaub18 |

|---|

randomized controlled trial hypothesis clearly described method of selection from source population and representation described loss to follow-up reported main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings clearly described power calculation to detect a clinically important effect performed estimates of random variability and actual probability values provided

|

|

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Author’s Conclusions

Table 6Summary of Findings of Included Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Author’s Conclusion |

|---|

| Alcohol use |

|---|

| Riper15 (systematic review) |

|---|

Difference in alcohol consumption between e-therapy and no treatment at post-treatment (effect size ga)

Therapist-guided (data from 4 studies)

g = 0.23 (small effect); 95% CI 0.05, 0.41

(Adherence rate was not reported for interventions with therapist guidance) | “Internet interventions are effective in reducing adult alcohol consumption and inducing alcohol users to adhere to guidelines for low-risk drinking. This effect is small but from a public health point of view this may warrant large scale implementation at low cost of Internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse” (p 1) |

| Cannabis use |

|---|

| Tait16 (systematic review) |

|---|

Difference in cannabis use between e-therapy and no treatment at post-treatment (effect size ga)

Therapist-guided (data from 4 studies)

g = 0.17 (small effect); 95% CI 0.07, 0.26 | “Internet and computer interventions appear to be effective in reducing cannabis use in the short-term albeit based on data from few studies and across diverse samples” (p 295) |

| Schaub18 (RCT) |

|---|

Change in number of cannabis use days per week compared to baseline (mean)

Therapist-guided: 1.4; 95% CI 0.07, 0.61; P 0.02

Change in number of cannabis use days per week compared to wait list (mean)

Therapist-guided: 1.0; 95% CI −0.07, 0.47; P 0.03

23.7% of participants in e-therapy with guidance completed treatment | “Web-based self-help interventions supplemented by brief chat counseling are an effective alternative to face-to-face treatment” (p 1) |

| Gambling |

|---|

| Luquiens17 (RCT) |

|---|

Difference in PGSI score at post-treatment compared to baseline (mean; SD)

E-therapy with guidance: −1.64 (3.9)

Wait list: −1.32 (3.1)

(in the email group without guidance, the difference from baseline was larger than in the group with guidance; statistical significance not reported)

Dropout rate

E-therapy with guidance: 97.3%

Wait list: 83% | “Guidance could have aversively affected problem gamblers who had not sought help. Despite the lack of significant difference in efficacy between groups, this naturalistic trial provides a basis for the development of future Internet-based trials in individuals with gambling disorders” (p 1) |

- a

Effect size g = difference between groups in post treatment alcohol consumption score/SD; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; CBT = cognitive-behavior therapy; PGSI – Problem Gambling Severity Index score; SD = standard deviation

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

e-Therapy interventions for the treatment of substance use disorders and other addictions. Ottawa: CADTH; 2018 May. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.