NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-.

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].

Show detailsOVERVIEW

Introduction

Vigabatrin is a GABA derivative that is used in combination with other agents as therapy of refractory complex partial seizures and as monotherapy for infantile spasms. Vigabatrin is associated with a paradoxical decrease in serum enzyme levels during therapy, explained by its direct inhibition of aminotransferase activity. Vigabatrin has not been convincingly linked to cases of clinically apparent liver injury, but was linked to a fatal case of Reye syndrome in a child with severe developmental delay.

Background

Vigabatrin (vye ga' ba trin) is a vinyl derivative of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) that acts as a competitive inhibitor of GABA transaminase. Vigabatrin prevents the breakdown of GABA and thus may increase GABAergic, neuroinhibitory activity. Vigabatrin has been shown to be effective in reducing seizure activity as add on therapy in patients with refractory partial onset seizures. It was available in other countries for more than a decade before it was approved for use in the United States in 2009. Current indications include as adjuvant therapy in patients with refractory complex partial seizures and as monotherapy for infantile spasms in children ages 1 month to 2 years. Vigabatrin is available in tablets of 500 mg and as a powder for oral solution generically and under the brand name Sabril. The typical initial dose is 500 mg twice daily, with subsequent increases to a recommended average dose of 3000 mg daily in adults and 2000 mg in children 10 to 16 years of age. Doses for children with infantile spasms are weight based. Side effects may include fatigue, somnolence, nystagmus, tremor, blurred vision, memory impairment, mood changes, confusion and weight gain. Rare, but severe adverse events include visual loss, visual field constriction and retinal dysfunction, for which reason vigabatrin is available only through a restricted program that requires prospective ophthalmologic monitoring.

Hepatotoxicity

In controlled clinical trials, addition of vigabatrin to standard anticonvulsant therapy was reported to cause an immediate and marked decrease in serum enzyme levels that could be reproduced by simply mixing vigabatrin with plasma. In some instances, markedly raised serum ALT levels were found to rapidly fall into the normal range with treatment. Vigabatrin inhibits GABA transaminase and is thus suspected of also being an inhibitor of alanine and aspartate aminotransferase, accounting for its unusual effects on liver associated enzymes. In prelicensure clinical trials, there were no reports of serum enzyme elevations during treatment and no instances of clinically apparent liver injury. After its general availability, however, there have been isolated case reports of severe liver injury and hepatitis associated with vigabatrin use. The onset of injury was 3 to 10 months after starting vigabatrin and was largely hepatocellular. One case resulted in rapid death from liver failure and a second worsened despite stopping and ultimately required a course of immunosuppression with prednisone and azathioprine (Case 1). Thus, clinically apparent liver injury from vigabatrin may occur and can be severe, but is rare.

Likelihood score: D (possible rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

Vigabatrin is an amino acid derivative and is metabolized by many tissues in the body. It is unlikely to be directly hepatotoxic and is not reported to cause drug-drug interactions. Instances of liver injury from vigabatrin are likely to be due to hypersensitivity.

Outcome and Management

Patients who have developed serious hypersensitivity reactions to aromatic anticonvulsants such as phenytoin, carbamazepine and lamotrigine have later tolerated therapy with vigabatrin without recurrence. The structure of vigabatrin would suggest that it does not share sensitivity to other anticonvulsant agents.

Drug Class: Anticonvulsants

CASE REPORT

Case 1. Acute hepatitis attributed to vigabatrin.(1)

A 25 year old woman was found to have abnormal liver tests 10 months after starting vigabatrin for partial onset seizures. The serum bilirubin was minimally raised (2.0 mg/dL), but ALT values were 10 times and AST 8 times the upper limit of normal (Table). Vigabatrin was continued, but several weeks later she developed symptoms of fatigue and nausea and repeat blood testing showed persistence of the liver test abnormalities. Vigabatrin was stopped and she was referred for further evaluation. She denied a history of liver disease, alcohol abuse or risk factors for viral hepatitis. She was not taking other medications and denied use of over-the-counter drugs or herbal supplements. Physical examination was unremarkable and showed no fever or rash. Tests for acute hepatitis A, B and C were negative as were tests for EBV and CMV infection. Autoantibodies were not detected. Imaging of the liver by ultrasound was normal. A liver biopsy showed panlobular hepatitis with hepatocellular necrosis and inflammatory infiltrates of lymphocytes and eosinophils. Plasma cells and neutrophils were not prominent and there was no fat or fibrosis. Despite stopping vigabatrin, she continued to worsen and serum bilirubin rose to 4.1 mg/dL and prothrombin index fell to 54%. Because of the worsening and the possibility of autoimmune liver injury, prednisone and azathioprine were started, but blood tests had already showed evidence of improvement. Thereafter, she improved rapidly, and she was asymptomatic and all tests were normal one month later. The immunosuppressive therapy was gradually tapered and was stopped after 4 months. In follow up 8 months later, all liver tests remained normal.

Key Points

| Medication: | Vigabatrin |

|---|---|

| Pattern: | Hepatocellular (R ratio=6.6) |

| Severity: | Moderate (jaundice and hospitalization) |

| Latency: | 10 months |

| Recovery: | 2 months (with prednisone and azathioprine therapy) |

| Other medications: | None |

Laboratory Values

| Time After Starting | Time After Stopping | ALT* (U/L) | Alk P (U/L) | Bilirubin* (mg/dL) | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 months | 0 | 35 | 0.6 | On therapy | |

| 10 months | 0 | 400 | 2.0 | ||

| 10.5 months | 0 | 440 | 125 | 2.4 | Vigabatrin stopped |

| 1 week | 1680 | 4.1 | |||

| 11 months | 2 weeks | 1200 | 3.0 | Prednisone started | |

| 3 weeks | 640 | 2.2 | |||

| 1 month | 45 | 1.3 | |||

| 1 year | 2 months | 35 | 0.7 | ||

| 4 months | 30 | 0.6 | Prednisone stopped | ||

| 2 years | 1 year | 30 | 0.5 | Asymptomatic | |

| Normal Values | <40 | <125 | <1.2 | ||

- *

Estimated from Figure 1 and converted to U/L based upon default normal values.

Comment

A woman with partial onset seizures developed evidence of acute hepatitis 10 months after starting vigabatrin. She was taking no other medications and had no risk factors for viral hepatitis. Medical evaluation revealed no evidence for other forms of liver disease, and a liver biopsy was compatible with drug induced liver injury. Because of concerns over the severity of the injury and the possibility of an early autoimmune hepatitis, prednisone and azathioprine were started, but blood tests showed evidence of improvement even before these medications was started. In follow up, she was able to stop the immunosuppressive regimen without recurrence of injury, strong evidence against autoimmune hepatitis. This was a fairly convincing case of vigabatrin induced liver injury. The absence of other reports may merely reflect the fact that the drug is rarely used, particularly as monotherapy. Vigabatrin is approved in the United States, only as adjunctive therapy to be used with other anticonvulsant agents for partial seizures in adults. Its serious adverse events (particularly retinal) have limited it more wide scale use. Why a simple GABA derivative would cause liver toxicity is unclear. Despite the absence of signs of hypersensitivity, the most likely explanation is immunologic.

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Vigabatrin – Generic, Sabril®

DRUG CLASS

Anticonvulsants

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

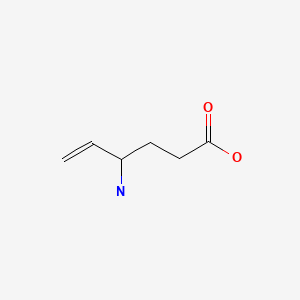

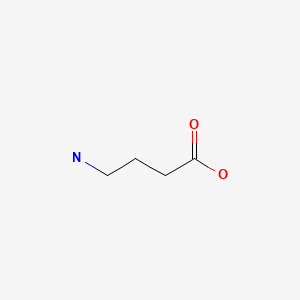

CHEMICAL FORMULAS AND STRUCTURES

| DRUG | CAS REGISTRY NO. | MOLECULAR FORMULA | STRUCTURE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vigabatrin | 68506-86-5 | C6-H11-N-O2 |

|

| GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid) | 56-12-2 | C4-H9-N-O2 |

|

CITED REFERENCE

- 1.

- Locher C, Zafrani ES, Dhumeaux D, Mallat A. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2001;25:556–7. [Vigabatrin-induced cytolytic hepatitis] French. [PubMed: 11521114]

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 31 July 2020

Abbreviations used: SJS/TEN, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Kaplowitz Zimmerman HJ. Anticonvulsants. In, Zimmerman, HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999: pp. 498-516.(Expert review of anticonvulsants and liver injury published in 1999 before the availability of vigabatrin).

- Pirmohamed M, Leeder SJ. Anticonvulsant agents. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013: pp 423-42.(Review of anticonvulsant induced liver injury; vigabatrin is not discussed).

- Smith MD, Metcalf CS, Wilcox KS. Pharmacology of the epilepsies. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp. 303-26.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Remy C, Beaumont D. Efficacy and safety of vigabatrin in the long-term treatment of refractory epilepsy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;27 Suppl 1:125S–129S. [PMC free article: PMC1379691] [PubMed: 2757903](Among 254 patients with refractory seizures treated with vigabatrin for an average of 23 months, “there was some alterations in liver transaminases” including a 30-50% decrease in ALT).

- Ben-Menachem E, Persson L, Mumford J. Long-term evaluation of once daily vigabatrin in drug-resistant partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1990;5:240–6. [PubMed: 2116964](Among 35 patients with refractory partial onset seizures treated with adjunctive vigabatrin for up to 3 years, there were no changes in routine chemistry laboratory tests “that were considered to be clinically significant”).

- Browne TR, Mattson RH, Penry JK, Smith DB, Treiman DM, Wilder BJ, Ben-Menachem E, et al. Multicenter long-term safety and efficacy study of vigabatrin for refractory complex partial seizures: an update. Neurology. 1991;41:363–4. [PubMed: 2006001](Among 66 patients with refractory seizures who received vigabatrin as add on therapy for 5-72 months, there were no abnormalities in laboratory studies).

- Tartara A, Manni R, Galimberti CA, Morini R, Mumford JP, Iudice A, Perucca E. Six-year follow-up study on the efficacy and safety of vigabatrin in patients with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;86:247–51. [PubMed: 1414241](Among 25 patients with partial onset seizures with a favorable response to adjunctive vigabatrin therapy and who were continued on treatment for 2-6 years, “there were no significant changes in standard…blood chemistry…tests” and no serious adverse events or need for discontinuation due to liver injury).

- Cocito L, Maffini M, Loeb C. Vigabatrin in chronic epilepsy: a 7-year follow-up study of responder patients. Seizure. 1993;2:301–7. [PubMed: 8162400](Among 35 adults with epilepsy treated with vigabatrin as add on therapy for refractory epilepsy, 23 were continued on drug in an extension study, among whom there were “no significant effects” on any of the routine laboratory tests).

- Williams A, Goldsmith R, Coakley J. Profound suppression of plasma alanine aminotransferase activity in children taking vigabatrin. Aust N Z J Med. 1994;24:65. [PubMed: 8002862](Among 12 children [ages 2 to 17 years] with poorly controlled seizures who were treated with vigabatrin, serum ALT levels decrease in all 12, from 13-72 U/L to 0-26 U/L, perhaps due to inhibition of alanine and aspartate as well as GABA transaminase).

- Kellermann K, Soditt V, Rambeck B, Klinge O. Fatal hepatotoxicity in a child treated with vigabatrin. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;93:380–1. [PubMed: 8800351](3 year old boy with developmental delay and seizures treated with phenobarbital developed fever and coma 3 months after the addition of vigabatrin [bilirubin not given, AST 54 rising to 577 U/L, ammonia 214 μmol/L] and progressive coagulopathy leading to death in 3 days, autopsy showing massive necrosis without fat, although mitochondrial changes suggested Reye syndrome).

- Williams A, Sekaninova S, Coakley J. Suppression of elevated alanine aminotransferase activity in liver disease by vigabatrin. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:395–7. [PubMed: 9727187](In a 16 month old boy with Alpers syndrome, severe developmental delay and liver disease, addition of vigabatrin to standard anticonvulsant therapy was followed by day 15 by a 91% decrease in ALT [247 to 18 U/L] and 19% decrease in Alk P levels [into the normal range], effects that could be reproduced in vitro, by addition of vigabatrin to plasma).

- Bruni J, Guberman A, Vachon L, Desforges C. Vigabatrin as add-on therapy for adult complex partial seizures: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study. The Canadian Vigabatrin Study Group. Seizure. 2000;9:224–32. [PubMed: 10777431](Among 111 patients with refractory partial onset seizures who were treated with vigabatrin or placebo for 36 weeks, there were “no clinically significant abnormalities” of laboratory test results).

- Guberman A, Bruni J. Long-term open multicentre, add-on trial of vigabatrin in adult resistant partial epilepsy. The Canadian Vigabatrin Study Group. Seizure. 2000;9:112–8. [PubMed: 10845734](Among 97 patients with refractory partial onset seizures who had completed participation in a placebo controlled trial and were continued on vigabatrin for up to 1 year, there were marked reductions in serum ALT, and no patient had a liver related serious adverse event or had to discontinue therapy because of liver injury).

- Locher C, Zafrani ES, Dhumeaux D, Mallat A. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2001;25:556–7. [Vigabatrin-induced cytolytic hepatitis] French. [PubMed: 11521114](25 year old woman with partial onset seizures developed acute hepatitis 10 months after starting vigabatrin [bilirubin 2.0 rising to 4.1 mg/dL, ALT 10 rising to 45 times ULN, Alk P 1.5 times ULN), ultimately treated with prednisone and azathioprine and improving rapidly, but able to stop all immunosuppression several months later without relapse: Case 1).

- Galindo PA, Borja J, Gómez E, Mur P, Gudín M, García R, Encinas C, et al. Anticonvulsant drug hypersensitivity. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2002;12:299–304. [PubMed: 12926190](Among 15 patients with cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to anticonvulsants [9 accompanied by liver test elevations] which were caused by carbamazepine [n=8], phenytoin [5], lamotrigine [4], phenobarbital [4], valproate [1] and felbamate [1], two patients later tolerated vigabatrin without recurrence).

- Björnsson E. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiepileptic drugs. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:281–90. [PubMed: 18341684](Review of the hepatotoxicity of anticonvulsants; no discussion of vigabatrin).

- Camposano SE, Major P, Halpern E, Thiele EA. Vigabatrin in the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a retrospective chart review of efficacy and safety profile. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1186–91. [PubMed: 18479386](Among 84 children treated with vigabatrin for infantile spasms or partial onset seizures or both, side effects were uncommon and usually mild, leading to discontinuation in only 3 children, all 3 for psychiatric symptoms).

- Vigabatrin (Sabril) for epilepsy. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2010;52(1332):14–6. [PubMed: 20208475](Concise summary of mechanism of action, clinical efficacy, adverse events and costs of vigabatrin shortly after its approval for use in the US mentions the serious adverse events of retinal dysfunction, intramyelinic edema and suicidal ideation as well as the common adverse events of anticonvulsants such as headache, fatigue, pain, ataxia, dizziness, somnolence, weight gain, depression and alterations in behavior, mood and thinking; no mention of ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

- Walker SD, Kälviäinen R. Non-vision adverse events with vigabatrin therapy. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2011;(192):72–82. [PubMed: 22061182](Review of the common adverse events of vigabatrin therapy does not mention ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

- Gaitatzis A, Sander JW. The long-term safety of antiepileptic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:435–55. [PubMed: 23673774](Review of the long term safety and adverse event profile of anticonvulsants mentions that valproate and felbamate can cause liver failure, but does not mention hepatotoxicity of other anticonvulsants).

- Drugs for epilepsy. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2013;11:9–18. Erratum in Treat Guidel Med Lett 2013; 11: 112. [PubMed: 23348233](Concise review of indications and side effects of anticonvulsants; vigabatrin is approved as add on therapy of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in children and adults; discussion of adverse effects does not mention hepatotoxicity, but mentions that vigabatrin is a mild inducer of CYP 3A4).

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419–25. [PubMed: 23419359](In a population based study of drug induced liver injury from Iceland, 96 cases were identified over a 2 year period, but of the 96, none were attributed to vigabatrin).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al. United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1340–52.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, 40 [4.5%] were attributed to anticonvulsants, but none to vigabatrin).

- Vidaurre J, Gedela S, Yarosz S. Antiepileptic drugs and liver disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;77:23–36. [PubMed: 29097018](Review of the use of anticonvulsants in patients with liver disease recommends use of agents that have little hepatic metabolism such as levetiracetam, lacosamide, topiramate, gabapentin and pregabalin, levetiracetam, being an "ideal" first line therapy for patients with liver disease because of its safety and lack of pharmacokinetic interactions).

- Drugs for epilepsy. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59(1526):121–30. [PubMed: 28746301](Concise review of the drugs available for therapy of epilepsy lists vigabatrin as being available only through a restricted distribution program because of concerns about retinal toxicity; no mention of hepatotoxicity or changes in ALT levels).

- Borrelli EP, Lee EY, Descoteaux AM, Kogut SJ, Caffrey AR. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis with antiepileptic drugs: An analysis of the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Epilepsia. 2018;59:2318–24. [PMC free article: PMC6420776] [PubMed: 30395352](Review of adverse event reports to the FDA between 2014 and 2018 identified ~2.9 million reports, 1034 for SJS/TEN, the most common class of drugs being anticonvulsants with 17 of 34 having at least one report, those most frequently linked being lamotrigine [n=106], carbamazepine [22], levetiracetam [14], phenytoin [14], valproate [9], clonazepam [8] and zonisamide [7]; no mention of vigabatrin).

- Somoza EC, Winship D, Gorodetzky CW, Lewis D, Ciraulo DA, Galloway GP, Segal SD, et al. A multisite, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of vigabatrin for treating cocaine dependence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:630–7. [PubMed: 23575810](Among 186 adults with cocaine dependency treated with vigabatrin or placebo for 13 weeks, abstinence rates were similar [7.6% vs 5.3%] as were adverse event rates, although one vigabatrin treated subject developed acute hepatitis [specific data not provided]).

- Jackson MC, Jafarpour S, Klehm J, Thome-Souza S, Coughlin F, Kapur K, Loddenkemper T. Effect of vigabatrin on seizure control and safety profile in different subgroups of children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1575–85. [PubMed: 28691157](Among 103 children treated with vigabatrin with electronic medical record follow up data, seizure frequency decreased by at least half in 73% of children while 20% of children had adverse events, the most common being visual changes [8.5%]; no mention of ALT abnormalities or hepatotoxicity).

- Ohtsuka Y. Efficacy and safety of vigabatrin in Japanese patients with infantile spasms: Primary short-term study and extension study. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;78:134–41. [PubMed: 29190579](Among 13 Japanese children with infantile spasms treated with vigabatrin, 8 [62%] had a 50% or greater decrease in seizure frequency and none had a serious adverse event or peripheral visual defect reported).

- Hussain SA. Treatment of infantile spasms. Epilepsia Open. 2018;3 Suppl 2:143–54. [PMC free article: PMC6293071] [PubMed: 30564773](Review of the clinical features, natural history and therapy of infantile spasms, the most common form of epilepsy presenting in the first year of life, vigabatrin being a first line therapy which is limited by concerns of retinopathy and MRI evidence of central nervous system toxicity associated with long term use; no mention of hepatotoxicity or ALT elevations).

- Cano-Paniagua A, Amariles P, Angulo N, Restrepo-Garay M. Epidemiology of drug-induced liver injury in a University Hospital from Colombia: Updated RUCAM being used for prospective causality assessment. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:501–7. [PubMed: 31053545](Among 286 patients with liver test abnormalities seen in a single hospital in Colombia over a 1 year period, 17 were diagnosed with drug induced liver injury, the most common cause being antituberculosis therapy [n=6] followed by anticonvulsants [n=3, 1 each due to phenytoin, gabapentin and valproate]).

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Vigabatrin with hormonal treatment versus hormonal treatment alone (ICISS) for infantile spasms: 18-month outcomes of an open-label, randomised controlled trial.[Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2...]Vigabatrin with hormonal treatment versus hormonal treatment alone (ICISS) for infantile spasms: 18-month outcomes of an open-label, randomised controlled trial.O'Callaghan FJK, Edwards SW, Alber FD, Cortina Borja M, Hancock E, Johnson AL, Kennedy CR, Likeman M, Lux AL, Mackay MT, et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018 Oct; 2(10):715-725. Epub 2018 Aug 29.

- Review Vigabatrin for infantile spasms.[Pharmacotherapy. 2011]Review Vigabatrin for infantile spasms.Pesaturo KA, Spooner LM, Belliveau P. Pharmacotherapy. 2011 Mar; 31(3):298-311.

- A lack of clinically apparent vision loss among patients treated with vigabatrin with infantile spasms: The UCLA experience.[Epilepsy Behav. 2016]A lack of clinically apparent vision loss among patients treated with vigabatrin with infantile spasms: The UCLA experience.Schwarz MD, Li M, Tsao J, Zhou R, Wu YW, Sankar R, Wu JY, Hussain SA. Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Apr; 57(Pt A):29-33. Epub 2016 Feb 23.

- Review Vigabatrin.[Ann Pharmacother. 1993]Review Vigabatrin.Connelly JF. Ann Pharmacother. 1993 Feb; 27(2):197-204.

- OV329, a novel highly potent γ-aminobutyric acid aminotransferase inactivator, induces pronounced anticonvulsant effects in the pentylenetetrazole seizure threshold test and in amygdala-kindled rats.[Epilepsia. 2021]OV329, a novel highly potent γ-aminobutyric acid aminotransferase inactivator, induces pronounced anticonvulsant effects in the pentylenetetrazole seizure threshold test and in amygdala-kindled rats.Feja M, Meller S, Deking LS, Kaczmarek E, During MJ, Silverman RB, Gernert M. Epilepsia. 2021 Dec; 62(12):3091-3104. Epub 2021 Oct 7.

- Vigabatrin - LiverToxVigabatrin - LiverTox

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...