Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-.

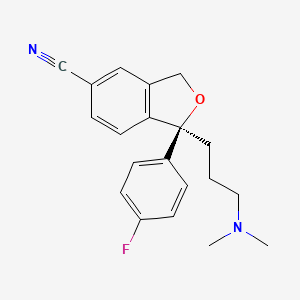

CASRN: 128196-01-0

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Escitalopram is the active S-isomer of the antidepressant, citalopram. Limited information indicates that maternal doses of escitalopram up to 20 mg daily produce low levels in milk and would not be expected to cause any adverse effects in breastfed infants, especially if the infant is older than 2 months. If escitalopram is required by the mother, it is not a reason to discontinue breastfeeding. A safety scoring system finds escitalopram use to be possible during breastfeeding.[1] One case of necrotizing enterocolitis was reported in a breastfed newborn whose mother was taking escitalopram during pregnancy and lactation, but causality was not established. A seizure-like event occurred in an infant who was also exposed to bupropion in milk. Other minor behavioral problems have also been reported. Monitor the infant for excess drowsiness, restlessness, agitation, poor feeding and poor weight gain, especially in younger, exclusively breastfed infants and when using combinations of psychotropic drugs.

Mothers taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) like escitalopram during pregnancy and postpartum may have more difficulty breastfeeding, although this might be a reflection of their disease state.[2] These mothers may need additional breastfeeding support. Infants exposed to an SSRI during the third trimester of pregnancy have a lower risk of poor neonatal adaptation if they are breastfed than formula-fed infants.

Drug Levels

Escitalopram is the S -isomer of racemic citalopram which is metabolized to 2 metabolites, each having antidepressant activity considered to be about 13% that of citalopram.[3]

Maternal Levels. Eight women taking escitalopram in an average dosage of 199 mcg/kg daily (10 to 20 mg daily) had 6 to 8 milk steady-state milk samples analyzed over the 24-hour interval after their single daily dose. The average dosage that an exclusively breastfed infant would receive was calculated to be 7.6 mcg/kg of escitalopram and 3 mcg/kg of desmethylcitalopram daily which were 3.9% and 1.7% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosages, respectively. The absolute dosage was about 40% less than a previous study by the same authors with racemic citalopram.[4]

A woman taking escitalopram had milk escitalopram concentrations measured twice. While taking a dosage of 5 mg daily, milk escitalopram was 24.9 mcg/L at 20 hours after the dose. While taking 10 mg escitalopram daily and valproic acid 1200 mg daily, milk escitalopram was 76.1 mcg/L at 15 hours after the dose. Using these two data points, the authors estimated that the infant received 5.1% and 7.7% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage of escitalopram on these days, respectively.[5]

One woman was taking escitalopram 20 mg daily and reboxetine 4 mg daily orally while nursing her 9.5-month-old infant. She collected milk samples before each breastfeeding session over a 1-day period. The authors estimated that the infant would receive 4.6% of the maternal-weight-adjusted dosage of escitalopram plus desmethylescitalopram.[6]

A nursing mother was taking escitalopram 20 mg daily. Foremilk and hindmilk samples taken at 1 week postpartum, 12 hours after a dose contained 173 mcg/L and 195 mcg/L, respectively. The samples also contained 21 mcg/L and 24 mcg/L of S -desmethylcitalopram in foremilk and hindmilk, respectively.[7]

Eighteen lactating women taking escitalopram in a mean daily dosage of 10 mg (range 2.5 to 30 mg [mean 0.2 mg/kg daily]) donated 3 to 5 random milk samples over a 24-hour period (n = 104 samples). The mean peak milk levels were 84.3 and 84.7 mcg/L for the 10 and 20 mg daily doses, respectively. Women taking 30 mg daily had an average peak milk level of 202 mcg/L. The average milk levels were 32.9 mcg/L with a dose of 10 mg daily, 49.8 mcg/L with a 20 mg dose and 136 mcg/L with 30 mg daily. Hindmilk concentrations averaged 10% higher than foremilk values. With a dose of 20 mg daily, the infant dosage was calculated to be 0.0078 mg/kg daily or 2.6% of the weight-adjusted maternal dosage.[8]

Nursing women taking either citalopram or escitalopram provided foremilk and hindmilk samples once during the first week postpartum (n = 29) and again at 1 month postpartum (n = 23) for a total of 104 milk samples. These samples together with paired blood samples were used to create a population pharmacokinetic model of escitalopram excretion into breastmilk using NONMEM. Genomic testing was also performed on blood samples and milk content was analyzed. With a maternal dose of 10 mg daily, the final model predicted that an exclusively breastfed infant would receive a median of 0.005 mg/kg daily (range: 0.001 to 0.016 mg/kg daily), which corresponds to median weight-adjusted dosage of 3.3%; (range 0.8% to 11.3%). The relative infant dosage would be 5.5% for infants whose mothers are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers compared to 3% in other phenotypes. The active metabolite did not contribute markedly to overall infant exposure.[9]

Infant Levels. One study found that racemic citalopram serum levels in infants were determined by their CYP2C19 genotype, with slow metabolizers more likely to have detectable serum levels.[10] Pharmacogenetics likely plays a part in determining the exposure of breastfed infants to escitalopram also.

In 8 breastfed infants whose mothers were taking an average of 199 mcg/kg daily of escitalopram (10 or 20 mg daily), escitalopram and desmethylescitalopram were undetectable in the serum of 3 infants (<1 mcg/L). The drug and metabolite serum levels were less than 5 mcg/L in all the other infants. Their mothers' serum levels of the drug and metabolite averaged 24 and 20 mcg/L, respectively.[4]

Eighteen lactating women taking escitalopram in a mean daily dosage of 10 mg (range 2.5 to 30 mg [mean 0.2 mg/kg daily]) donated 3 to 5 random milk samples over a 24-hour period (n = 104 samples). The data were used to construct a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model simulating 1600 infant serum levels whose mothers received a dose of 20 mg daily. The predicted average infant serum concentrations were 1.7% (range, 0.5 to 5.9%) of the average maternal serum concentrations. Age of the infant from birth to 1 year did not substantially impact the results.[8]

Effects in Breastfed Infants

Eight breastfed infants whose mothers were taking escitalopram in an average dose of 199 mcg/kg daily for postpartum depression were evaluated by a pediatric specialist using the Denver developmental scale. Their mothers had taken escitalopram for a median of 55 days postpartum (range 23 to 240 days). The infants' scores on this scale was 110% of normal.[4]

A woman began taking escitalopram 5 mg daily immediately after birth. Her dosage was increased to 10 mg daily and valproic acid 1200 mg daily was added by 7 weeks postpartum. Her breastfed infant was judged to be healthy and have normal neuropsychological development by a general practitioner at 7.5 weeks of age.[5]

One woman was taking escitalopram 20 mg daily and reboxetine 4 mg daily orally while nursing her infant (extent not stated). She had taken reboxetine for 1.5 months, but the start of her escitalopram therapy was not stated. At 9.5 months of age, her breastfed infant had normal weight gain and a Denver developmental score of 105% of chronological age.[6]

A nursing mother was given escitalopram 10 mg daily for depression beginning at 3 weeks postpartum and increasing to 20 mg daily thereafter. At 4 months of age, her exclusively breastfed infant was admitted to the hospital for irritability, vomiting and fever of 4 days duration. He had been irritable with prolonged periods of crying for the past 3 months according to his mother and had gained only 400 grams per month since birth. Liver enzymes were moderately elevated. The infant was discharged after 5 days and breastfeeding was continued, but only twice daily for 2 weeks, then discontinued at 4.5 months of age. At 5 months, symptom improvement was noted and at 6 months, serum liver enzymes had normalized. The author noted that the time course of the adverse effects were consistent with the treatment with escitalopram.[11]

A mother began taking escitalopram 20 mg daily in the morning on day 15 postpartum. She exclusively breastfed her infant on demand. At 3 months of age, no adverse effects had been reported in the infant by his pediatrician.[12]

At 5 days of age, an infant was readmitted to the neonatal intensive care unit with a diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis. The infant had spent the first 2 days of life in intensive care because of respiratory distress. The infant's mother had taken escitalopram 20 mg daily throughout pregnancy and while breastfeeding (extent not stated). The authors hypothesized that escitalopram might have been responsible for the enterocolitis because of its effect on platelet aggregation.[13] The drug was possibly a cause of the reaction.

One author reported on the newborn infant of a mother who was taking escitalopram (dose and duration not stated). The hyperirritable infant had high-pitched crying 2 hours after breastfeeding every afternoon which was 5 to 6 hours after maternal dose of escitalopram. Changing the time of the mother's escitalopram dose resulted in a shift in the time of the infant's crying at the same time interval after the dose. The infant's symptoms improved with partial substitution of formula and ceased on day 11 of life with complete formula feeding.[14]

An uncontrolled online survey compiled data on 930 mothers who nursed their infants while taking an antidepressant. Infant drug discontinuation symptoms (e.g., irritability, low body temperature, uncontrollable crying, eating and sleeping disorders) were reported in about 10% of infants. Mothers who took antidepressants only during breastfeeding were much less likely to notice symptoms of drug discontinuation in their infants than those who took the drug in pregnancy and lactation.[15]

A 6.5-month-old infant developed severe vomiting and an apparent tonic seizure after being breastfed by her mother. The mother had been taking escitalopram 10 mg daily since birth and had begun extended-release bupropion 150 mg daily 3 weeks earlier. The seizure occurred 8 hours after the mother's morning dose of bupropion. The infant's mother had noted disturbances in sleep behavior, unusual movements, and unresponsiveness followed by sleep on several previous occasions. The baby was partially breastfed, also receiving pumped breastmilk, formula, and solid foods. Breastfeeding was discontinued and the baby was discharged after being asymptomatic for 48 hours. The seizure was probably drug-related, most likely caused by bupropion and hydroxybupropion in breastmilk, but a contribution by escitalopram cannot be ruled out.[16]

A cohort of 247 infants exposed to an antidepressant in utero during the third trimester of pregnancy were assessed for poor neonatal adaptation (PNA). Of the 247 infants, 154 developed PNA. Infants who were exclusively given formula had about 3 times the risk of developing PNA as those who were exclusively or partially breastfed. None of the infants were exposed to escitalopram in utero, but 51 were exposed to citalopram, the racemic form of the drug.[17]

A case-control study in Israel compared 280 infants of nursing mothers taking long-term psychotropic drugs to the infants of 152 women taking antibiotics. Infant sleepiness at 3 days of age was reported by 3 mothers taking escitalopram during pregnancy and breastfeeding and by none taking antibiotics. The sleepiness resolved within 24 hours with no developmental effect.[18]

A mother with mixed anxiety-depressive order was taking sertraline and breastfeeding her 9-month-old infant. Because of side effects, sertraline was stopped and citalopram 10 daily was started. After 2 weeks of therapy, she reported signs of bruxism in her infant who was breastfed 5 to 6 times daily, as well as supplementary feedings such as fruits, vegetables, meat, and biscuits. The infant had sporadic, pulsatile, and momentary movements in her jaws, which usually began with movements of the head, especially during sleep. Furthermore, the mother mentioned her child had a habit of biting and clenching her teeth while awake. Pediatric and dental examinations found no abnormalities, but the dentist observed bruxism during the examination. Citalopram was discontinued and bruxism symptoms resolved after 72 hours. The mother resumed breastfeeding with no return of symptoms and the infant had no bruxism symptoms for the next 2 years.[20] Bruxism was probably caused by citalopram in breastmilk.

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

The SSRI class of drugs, including escitalopram, can cause increased prolactin levels and galactorrhea in nonpregnant, nonnursing patients.[19-29] Euprolactinemic galactorrhea has also been reported.[30-32] The prolactin level in a mother with established lactation may not affect her ability to breastfeed.

In a small prospective study, 8 primiparous women who were taking a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI; 3 taking fluoxetine and 1 each taking citalopram, duloxetine, escitalopram, paroxetine or sertraline) were compared to 423 mothers who were not taking an SRI. Mothers taking an SRI had an onset of milk secretory activation (lactogenesis II) that was delayed by an average of 16.7 hours compared to controls (85.8 hours postpartum in the SRI-treated mothers and 69.1 h in the untreated mothers), which doubled the risk of delayed feeding behavior in the untreated group. However, the delay in lactogenesis II may not be clinically important, since there was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the percentage of mothers experiencing feeding difficulties after day 4 postpartum.[33]

A case control study compared the rate of predominant breastfeeding at 2 weeks postpartum in mothers who took an SSRI antidepressant throughout pregnancy and at delivery (n = 167) or an SSRI during pregnancy only (n = 117) to a control group of mothers who took no antidepressants (n = 182). Among the two groups who had taken an SSRI, 33 took citalopram, 18 took escitalopram, 63 took fluoxetine, 2 took fluvoxamine, 78 took paroxetine, and 87 took sertraline. Among the women who took an SSRI, the breastfeeding rate at 2 weeks postpartum was 27% to 33% lower than mother who did not take antidepressants, with no statistical difference in breastfeeding rates between the SSRI-exposed groups.[34]

An observational study looked at outcomes of 2859 women who took an antidepressant during the 2 years prior to pregnancy. Compared to women who did not take an antidepressant during pregnancy, mothers who took an antidepressant during all 3 trimesters of pregnancy were 37% less likely to be breastfeeding upon hospital discharge. Mothers who took an antidepressant only during the third trimester were 75% less likely to be breastfeeding at discharge. Those who took an antidepressant only during the first and second trimesters did not have a reduced likelihood of breastfeeding at discharge.[35] The antidepressants used by the mothers were not specified.

A retrospective cohort study of hospital electronic medical records from 2001 to 2008 compared women who had been dispensed an antidepressant during late gestation (n = 575) to those who had a psychiatric illness but did not receive an antidepressant (n = 1552) and mothers who did not have a psychiatric diagnosis (n = 30,535). Women who received an antidepressant were 37% less likely to be breastfeeding at discharge than women without a psychiatric diagnosis, but no less likely to be breastfeeding than untreated mothers with a psychiatric diagnosis.[36] None of the mothers were taking escitalopram.

In a study of 80,882 Norwegian mother-infant pairs from 1999 to 2008, new postpartum antidepressant use was reported by 392 women and 201 reported that they continued antidepressants from pregnancy. Compared with the unexposed comparison group, late pregnancy antidepressant use was associated with a 7% reduced likelihood of breastfeeding initiation, but with no effect on breastfeeding duration or exclusivity. Compared with the unexposed comparison group, new or restarted antidepressant use was associated with a 63% reduced likelihood of predominant, and a 51% reduced likelihood of any breastfeeding at 6 months, as well as a 2.6-fold increased risk of abrupt breastfeeding discontinuation. Specific antidepressants were not mentioned.[37]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

References

- 1.

- Uguz F. A new safety scoring system for the use of psychotropic drugs during lactation. Am J Ther 2021;28:e118-e126. [PubMed: 30601177]

- 2.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Leggett C, Costi L, et al. Impact of serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on breast milk supply in mothers of preterm infants: A retrospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:1373-9. [PMC free article: PMC5980248] [PubMed: 29522259]

- 3.

- Weissman AM, Levy BT, Hartz AJ, et al. Pooled analysis of antidepressant levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1066-78. [PubMed: 15169695]

- 4.

- Rampono J, Hackett LP, Kristensen JH, et al. Transfer of escitalopram and its metabolite demethylescitalopram into breastmilk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:316-22. [PMC free article: PMC1885141] [PubMed: 16934048]

- 5.

- Castberg I, Spigset O. Excretion of escitalopram in breast milk. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:536-8. [PubMed: 16974204]

- 6.

- Hackett LP, Ilett KF, Rampono J, et al. Transfer of reboxetine into breastmilk, its plasma concentrations and lack of adverse effects in the breastfed infant. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:633-8. [PubMed: 16699799]

- 7.

- Weisskopf E, Panchaud A, Nguyen KA, et al. Simultaneous determination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and their main metabolites in human breast milk by liquid chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2017;1057:101-9. [PubMed: 28511118]

- 8.

- Delaney SR, Malik PRV, Stefan C, et al. Predicting escitalopram exposure to breastfeeding infants: Integrating analytical and in silico techniques. Clin Pharmacokinet 2018;57:1603-11. [PubMed: 29651785]

- 9.

- Weisskopf E, Guidi M, Fischer CJ, et al. A population pharmacokinetic model for escitalopram and its major metabolite in depressive patients during the perinatal period: Prediction of infant drug exposure through breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2020;86:1642-53. [PMC free article: PMC7373710] [PubMed: 32162723]

- 10.

- Berle JØ, Steen VM, Aamo TO, et al. Breastfeeding during maternal antidepressant treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Infant exposure, clinical symptoms, and cytochrome P450 genotypes. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1228-34. [PubMed: 15367050]

- 11.

- Merlob P. Use of escitalopram during lactation. BELTIS Newsl 2005;Number 13:40-4.

- 12.

- Gentile S. Escitalopram late in pregnancy and while breast-feeding. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1696-7. [PubMed: 16912243]

- 13.

- Potts AL, Young KL, Carter BS, Shenai JP. Necrotizing enterocolitis associated with in utero and breast milk exposure to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, escitalopram. J Perinatol 2007;27:120-2. [PubMed: 17262045]

- 14.

- 15.

- Hale TW, Kendall-Tackett K, Cong Z, et al. Discontinuation syndrome in newborns whose mothers took antidepressants while pregnant or breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med 2010;5:283-8. [PubMed: 20807106]

- 16.

- Neuman G, Colantonio D, Delaney S, et al. Bupropion and escitalopram during lactation. Ann Pharmacother 2014;48:928-31. [PubMed: 24732787]

- 17.

- Kieviet N, Hoppenbrouwers C, Dolman KM, et al. Risk factors for poor neonatal adaptation after exposure to antidepressants in utero. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:384-91. [PubMed: 25559357]

- 18.

- Kronenfeld N, Ziv Baran, T, Berlin M, et al. Chronic use of psychotropic medications in breastfeeding women: Is it safe? PLoS One 2018;13:e0197196. [PMC free article: PMC5962050] [PubMed: 29782546]

- 19.

- Arya DK, Taylor WS. Lactation associated with fluoxetine treatment. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1995;29:697. [PubMed: 8825840]

- 20.

- Egberts AC, Meyboom RH, De Koning FH, et al. Non-puerperal lactation associated with antidepressant drug use. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997;44:277-81. [PMC free article: PMC2042834] [PubMed: 9296322]

- 21.

- Iancu I, Ratzoni G, Weitzman A, Apter A. More fluoxetine experience. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31:755-6. [PubMed: 1644743]

- 22.

- González Pablos E, Minguez MartÍn L, Hernández Fernández M, Sanguina Andrés RM. [A clinical case of galactorrhoea after citalopram treatment]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2001;29:414. [PubMed: 11730581]

- 23.

- Gulsun M, Algul A, Semiz UB, et al. A case with euprolactinemic galactorrhea induced by escitalopram. Int J Psychiatry Med 2007;37:275-8. [PubMed: 18314855]

- 24.

- Aggarwal A, Kumar R, Sharma RC, Sharma DD. Escitalopram induced galactorrhoea: A case report. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2010;34:557-8. [PubMed: 20138200]

- 25.

- Shim SH, Lee YJ, Lee EC. A case of galactorrhea associated with excitalopram (sic). Psychiatry Investig 2009;6:230-2. [PMC free article: PMC2796073] [PubMed: 20046401]

- 26.

- Suthar N, Pareek V, Nebhinani N, Suman DK. Galactorrhea with antidepressants: A case series. Indian J Psychiatry 2018;60:145-6. [PMC free article: PMC5914246] [PubMed: 29736080]

- 27.

- Pathania M, Goel B, Dhamija P, et al. A rare adverse drug reaction to escitalopram. J Family Med Prim Care 2018;7:466-467. [PMC free article: PMC6060945] [PubMed: 30090797]

- 28.

- McGrane IR, Morefield CM, Aytes KL. Probable galactorrhea associated with sequential trials of escitalopram and duloxetine in an adolescent female. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2019;29:788-9. [PubMed: 31339744]

- 29.

- Ozkan HM. Galactorrhea and hyperprolactinemia during vortioxetine use: Case report. Turk Biyokim Derg 2019;44:105-7. doi:10.1515/tjb-2018-0106 [CrossRef]

- 30.

- Mahasuar R, Majhi P, Ravan JR. Euprolactinemic galactorrhea associated with use of imipramine and escitalopram in a postmenopausal woman. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:341.e11-3. [PubMed: 20430243]

- 31.

- Praharaj SK. Euprolactinemic galactorrhea with escitalopram. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;26:E25-6. [PubMed: 25093774]

- 32.

- Kaba D, Oner O. Galactorrhea after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use in an adolescent girl: A case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2017;37:374-6. [PubMed: 28383361]

- 33.

- Marshall AM, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Hernandez LL, et al. Serotonin transport and metabolism in the mammary gland modulates secretory activation and involution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:837-46. [PMC free article: PMC2840848] [PubMed: 19965920]

- 34.

- Gorman JR, Kao K, Chambers CD. Breastfeeding among women exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy. J Hum Lact 2012;28:181-8. [PubMed: 22344850]

- 35.

- Venkatesh KK, Castro VM, Perlis RH, Kaimal AJ. Impact of antidepressant treatment during pregnancy on obstetric outcomes among women previously treated for depression: An observational cohort study. J Perinatol 2017;37:1003-9. [PMC free article: PMC10034861] [PubMed: 28682318]

- 36.

- Leggett C, Costi L, Morrison JL, et al. Antidepressant use in late gestation and breastfeeding rates at discharge from hospital. J Hum Lact 2017;33:701-9. [PubMed: 28984528]

- 37.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Saha MR, Nordeng H, et al. Perinatal antidepressant use and breastfeeding outcomes: Findings from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2022;101:344-54. [PMC free article: PMC9564556] [PubMed: 35170756]

Substance Identification

Substance Name

Escitalopram

CAS Registry Number

128196-01-0

Drug Class

Breast Feeding

Milk, Human

Antidepressive Agents

Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors

Antidepressive Agents, Second-Generation

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

- User and Medical Advice Disclaimer

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Record Format

- LactMed - Database Creation and Peer Review Process

- Fact Sheet. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed)

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Glossary

- LactMed Selected References

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - About Dietary Supplements

- Breastfeeding Links

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Review Citalopram.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Citalopram.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Fluvoxamine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Fluvoxamine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Domperidone.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Domperidone.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Bupropion.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Bupropion.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Duloxetine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Duloxetine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Escitalopram - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)Escitalopram - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...