NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Baba AI, Câtoi C. Comparative Oncology. Bucharest (RO): The Publishing House of the Romanian Academy; 2007.

Male genital tract tumors in animals are grouped as follows: penile and preputial tumors; testicular and epididymal tumors; and prostate tumors.

Histological Classification of Tumors of the Genital System (Kennedy et al. 1998)

MALE

- Tumors of the Testis

- 1.1 Sex cord-stromal (gonadostromal) tumors

- 1.1.1 Interstitial (Leydig) cell tumor

- 1.1.2 Sertoli (sustentacular) cell tumor

- 1.2 Germ cell tumors

- 1.2.1 Seminoma

- 1.2.2 Teratoma

- 1.2.3 Embryonal carcinoma

- 1.3 Mixed germ cell-sex cord stromal tumor

- Tumors Metastatic to the Testis

- Tumors of the Collecting System

- Tumors of the Testicular Adnexal Structures

- 4.1 Mesothelioma

- Miscellaneous Tumors of the Testis and Adnexa

- Tumorlike Lesions of the Epididymis

- 6.1 Adenomyositis of the epididymis

- Tumors of Accessory Reproductive Organs

- 7.1 Tumors and tumorlike lesions of the canine prostate

- 7.1.1 Hyperplasia of the prostate

- 7.1.2 Adenocarcinoma of the prostate

- 7.1.3 Mesenchymal tumors of the prostate

- 7.1.4 Tumors metastatic to the prostate

- Tumors of the Penis

- 8.1 Squamous papilloma

- 8.2 Squamous cell carcinoma

- 8.3 Transmissible venereal tumor

- 8.4 Fibropapilloma of cattle

- 8.5 Transmissible genital papilloma of pigs

12.1. TUMORS OF THE TESTIS

Primary testicular tumors are extremely frequent in older dogs, to a smaller extent in old bulls, and exceptionally in other species.

The incidence of different testicular neoplasms is almost exclusively evaluated for the canine species. The literature estimates the following proportion: sertolioma 33.75%; seminoma 31.25%; leydigoma 27.5%, while other tumors are sporadically found [30, 42]. Testicular tumors in dogs range on the 4th place of all neoplasms in this species, being about 15-fold more numerous compared to humans. However, mortality cases from testicular neoplasms are much fewer than in man, and metastases are less frequent.

The presence of two or more testicular neoplastic types in the same subject is relatively common, being estimated at 25% of cases. The only explanation of the presence of several types of testicular tumors would be advanced age, which predisposes different cell types to neoplastic change. Some breeds, such as Boxer and German Shepherd breeds, frequently develop testicular neoplasms, sometimes even at a younger age.

Cryptorchid males develop 10 times more testicular tumors compared to normal dogs. Canine testicular tumors are frequently located in the right testis, which is also true for cryptorchidism [20].

A classification of testicular tumors, according to NIELSEN and LEIN (1974), updated by LADDS (1993), includes the following categories:

- germ cell tumors: seminoma, embryonic carcinoma; teratoma;

- sex cord-stromal tumors: Sertoli cell tumors; interstitial (Leydig) cell tumors; intermediate Sertoli cell tumors and differentiated Leydig cell tumors;

- primary multiple tumors;

- mesothelioma;

- vascular stromal tumors;

- unclassified tumors.

12.1.1. Seminoma

Seminoma is a common tumor in dogs, being also diagnosed in stallions. Frequency is high in old and cryptochid subjects. Seminoma develops from the spermatogenic series, having multiple development foci in the parenchyma of the same testis. Local development is invasive.

Macroscopically, seminomas appear as nodules, sometimes 6 cm or more in diameter, deforming the albuginea. The tumor develops rapidly, hemorrhagic necrotic foci appear in section, as well as a fine, soft to moderately dense connective framework that delimits white or gray lobules. Color and structure are very similar to those of lymphoid tissue.

Microscopically, two forms are distinguished: invasive or non-invasive intratubular seminoma, and diffuse seminoma.

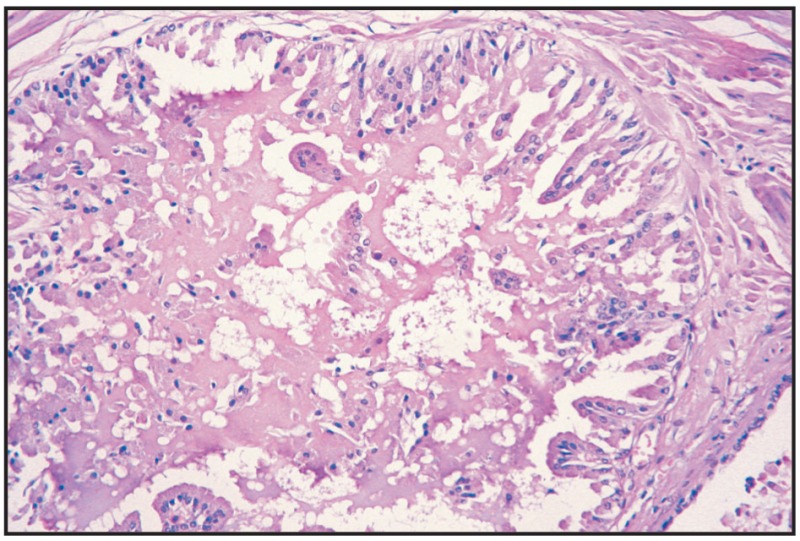

Intratubular seminoma is considered as the onset form of the neoplasm, and it may appear as a single microtumor or clusters in the seminiferous tubes, or with multicentric origin. An enlargement of the tubes is noted, through uniform, polyhedral, poorly basophilic cells, similar to spermatogonia, with the maintenance of intact basal membranes. Adjacent seminiferous tubes are atrophied. Tumor cells have large vesicular nuclei, with one or more prominent, highly acidophilic nucleoli. Tumor cells frequently pass through the basal membranes, invading testicular structures. Multinucleated cells with granular, acidophilic cytoplasm may be occasionally found. Lymphocyte accumulations under the form of foci or diffuse infiltration are frequently found, concomitantly with testicular degeneration (Fig. 12.9, 12.10).

Fig. 12.9

Intratubular seminoma.

Fig. 12.10

Intratubular seminoma.

Intratubular seminomas have also been diagnosed in mature and old rams, in stags and bulls.

Electron microscopically, tumor cells are similar to normal germinal epithelium and are characterized by a reduced number of cytoplasmic organelles, oval nuclei, unchanged border cells with obvious Golgi apparatus. Intercellular connections are found in normal germ cells.

Abdominal metastases are relatively frequent in stallions, reaching impressive sizes (over 9 kg), with possible thoracic metastases.

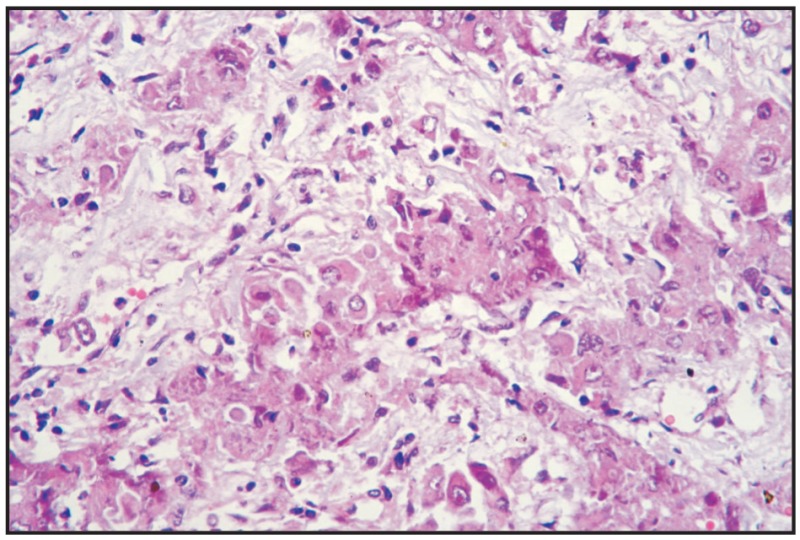

Diffuse seminoma is relatively frequently diagnosed, having a compact nest aspect, with diffuse infiltration, with uniform tumor cells. Cells are clearly outlined, large, round or polyhedral, with vesicular nuclei, with one or two prominent nucleoli. Multinucleated giant cells and vacuolized histiocytes are occasionally found. Normal or bizarre mitoses are present. In general, the stroma is reduced; sometimes it can delimit pseudolobules by vascular connective tissue. Nests or diffuse lymphocytic infiltration are common (Fig. 12.11, 12.12) [51, 52].

Fig. 12.11

Diffuse seminoma with starr-sky appearance.

Fig. 12.12

Diffuse seminoma with giant cells.

12.1.2. Teratoma

Teratoma is found in particular in the case of cryptorchidism in young stallions, being practically unknown in other species. Equine teratoma is a benign tumor, found in the scrotum or most frequently in the cryptorchid testes of young animals, even in newborn foals.

Macroscopically, teratoma may be single or multiple, of variable colors, from yellow to white. In section, it appears as a fibrous, adipose, cartilaginous or frequently bony mass.

Histologically, structure is derived from all embryonic folds, ectoderm (dermatoid cysts, hair, teeth), neuroectoderm (nerve tissue, melanoblasts) or mesoderm (fibrous or adipose tissue, bone, muscles), which can be concomitantly present. Nerve tissue is almost always present, and adipose tissue is extremely frequent. The testicular tissue adjacent to teratoma is atrophied, with reduced spermatogenesis [51, 52].

Embryonal carcinoma, a germ cell tumor composed of multipotential cells that are embryonic and anaplastic in appearance and arranged in a variety of patterns –acinar, tubular, papillary, or solid.

12.1.3. Sex cord-stromal (gonadostromal) tumors

These tumors are derived from Sertoli (sustentacular) cells or interstitial (Leydig) cells.

Sertoli cell tumor is common in dogs, especially in old subjects, being sporadically reported in other species, in bulls, horses, rams and cats. One of the characteristics of this neoplasm in dogs is the development of a feminisation syndrome, due to exaggerated estrogen secretion. This is also explained by the large tumor size [49].

The feminisation syndrome manifests by diminished libido, a typically feminine distribution of body fat, cutaneous and/or pilosebaceous atrophy, symmetric alopecia, testicular and penile atrophy, mammary estrogenic development, preputial swelling and squamous hyperplasia or metaplasia of the prostate that can be accompanied by perineal hernia. In the case of the appearance of the feminisation syndrome in cryptorchid dogs, this is a certain sign of the existence of sertolioma [22, 43, 49].

After the removal of the tumor, at approximately 1 month, the feminization signs also disappear; otherwise functional metastases may be suspected. Dogs with sertoliomas can manifest bone marrow hypoplasia, with pancytopenia, due to endogenous estrogen myelotoxicosis [9, 45]. Clinically, patients present hemorrhage caused by thrombocytopenia, anemia induced by hemorrhage and the diminution of erythrocyte production, infections and fever associated with granulocytopenia. Signs of the feminisation syndrome and prostate hypertrophy concomitantly appear. The authors recommend: castration, which suppresses the estrogen source; antibiotics in order to fight bacterial infections; transfusion; androgenic steroids for the stimulation of hematopoiesis and the systemic follow-up of the blood picture. Metastases are located in particular in lumbar lymph nodes, and later in the lungs and other viscera. The tumor frequently invades the sperm duct, which requires its surgical removal.

Macroscopically, the tumor usually has large sizes, being delimited by a fibrous capsule. In section it has a whitish color, dense consistency, sometimes with a cystic aspect.

Histologically, relatively abundant stroma is found, which confers a pseudotubular aspect or diffuse growth. Sertoli cells in incipient tumors are well differentiated, being similar to normal cells, they have a slightly elongated shape, the cytoplasm is acidophilic, with a foamy aspect, and nuclei are small, hyperchromatic, with a basal arrangement. In more advanced neoplastic forms, cells are less differentiated, elongated, with eosinophilic cytoplasm, nuclei being large, pleomorphic, situated towards the trabecular pole. In the case of highly malignant neoplasms, cells have oval-spherical shapes, the cytoplasm is eosinophilic, and nuclei have irregular, even bizarre forms, atypical mitoses being present. Hyaline deposits under the form of intracellular corpuscles have been noted (Fig. 12.13–12.16).

Fig. 12.13

Intratubular Sertoli cells tumor.

Fig. 12.14

Intratubular Sertoli cells tumor.

Fig. 12.15

Diffuse Sertoli cells tumor.

Fig. 12.16

Diffuse Sertoli cells tumor.

Electron microscopically, in Sertoli tumors in dogs, intercellular junctions are characteristic, while Charcot-Bottcher crystals are unusual in tumor cells. However, a number of cells with normal aspect are present, having a high number of intracytoplasmic organelles, which allows differentiation from Leydig tumor cells and seminoma. Prominent intercellular cells are obvious in Sertoli tumor cells in dogs.

In bulls and buffaloes, Sertoli cell tumors occurs at an advanced age, 9–14 years, but unlike in dogs, the tumor has been diagnosed in newborn and young calves. This suggests the possibility of the development of Sertoli cell tumor in the embryonic period with a possible genetic origin. The microscopic aspect is identical to that described in dogs. Similar aspects have been noted in rams and stallions, in extremely sporadic cases [20].

Mixed Sertoli and Leydig cell tumors are rare, such a tumor being diagnosed in a 6 month aged boar [24]. The neoplasms have metastases in the liver, spleen and peritoneum, as well as in inguinal lymph nodes. Microscopically, the tumor presents severe pleomorphism with abundant collagen fibers. Ultrastructurally, neoplastic cells show mitochondria with tubular vesicular crests, smooth endoplasmic reticulum, membranous structures, lysosomes, lipofuscin granules and lipid drops.

Interstitial (Leydig) cell tumors are relatively frequent in old dogs, as well as in bulls, especially the Guernsey breed; in stallions they develop almost exclusively in cryptorchid subjects, being also reported in rams and male goats. The tumor is usually bilateral, and it clinically manifests by increased aggressiveness. Histologically, large, highly hyperplastic, eosinophilic cells appear along with pleomorphic, frequently fusiform cells, with fibrillar or vacuolated cytoplasm. Cells are arranged in nodules or bundles [14].

Macroscopically, Leydig cell tumors in dogs frequently appears as a multiple tumor, but it is also solitary, uni- or bilateral. The neoplasm has small sizes, between 1 mm and 2 cm in diameter, exceptionally larger. The tumor surface is well delimited by a capsule, of spheroid shape and yellowish color; hemorrhagic necroses and degenerative cysts are frequent, especially in dogs.

Leydig cell tumor can be histologically differentiated into: the diffuse compact type; the vascular-cystic or angiomatoid type and the pseudoadenomatous type [29].

Diffuse compact Leydig cell tumors has the aspect of a hyperplastic nodule, which makes difficult differentiation from a benign tumor. Solid Leydig cell tumors consist of extensive, uniform, polyhedral, well outlined, intensely colored cell proliferations. The stroma is delicate, with numerous capillaries. Tumor cells are frequently arranged in a palisade pattern around the vessels, with nuclei situated at the pole opposite to vessels, and sometimes cells are apparently arranged in rosettes. The cell cytoplasm contains clear vacuoles and yellow-gold granules of lipochrome pigment. Nuclei are small, round and hyperchromatic, with fine chromatin granules, nucleoli are small, and mitoses are generally absent (Fig. 12.17 and 12.18).

Fig. 12.17

Solid diffuse Leydig cell tumor.

Fig. 12.18

Solid diffuse Leydig cell tumor.

Vascular-cystic or angiomatoid Leydig cell tumor is characterized by the presence of spaces between tumor cells, filled with protein liquid, with erythrocytes, or apparently empty spaces. Cells are arranged in cords composed of two or more layers of large cells, bordered by vascular stroma. Numerous large vessels are present in the tumor structure and small arterioles are frequently bordered by elongated tumor cells arranged in rosettes (Fig. 12.19 and 12.20).

Fig. 12.19

Angiomatoid Leydig cell tumor.

Fig. 12.20

Angiomatoid Leydig cell tumor.

Pseudoadenomatous Leydig cell tumor is characterized by tumor cell masses isolated by capillaries and vascular stroma. Pseudolobules are formed by groups of 10–30 cells delimited by stromal septa, clear microcavities or spaces, bordered by vascular stroma (Fig. 12.21).

Fig. 12.21

Pseudoadenomatous Leydig cell tumor.

Regardless of the Leydig cell tumors type, tumor cells are large, round and polyhedral, with abundant granular or vacuolated cytoplasm, frequently containing lipochrome pigment. In bulls, the cytoplasm does not contain vacuoles, only very few lipids. Sometimes, cells are fusiform, poorly outlined and arranged in a palisade pattern.

A particular aspect is represented by intranuclear cytoplasmic invaginations, forming intranuclear pseudoinclusions, present in 15% of canine leydigomas. These inclusions are PAS-positive and are composed of smooth and rough endoplasmic reticulum, lipid vesicles and vacuoles, myelin processes and membranous fragments, aspects that have not been identified in other testicular tumors. Nuclei that present such structures are large. Electron microscopically, tumor cells are similar to normal cells, except for the presence of these invaginations [44].

The secretory activity of Leydig cell tumor is not obvious. However, it seems that interstitial tumor cells produce steroid hormones, which is demonstrated by testicular degeneration and prostate hyperplasia. Lesions associated with leydigoma have been reported, such as hepatic telangiectasia, tumors of the parafollicular thyroid cells (C cells), and infertility in Guernsey bulls.

Multiple primary tumors of epithelial origin have been reported, which appear simultaneously in the same testis or in both testes. Microscopically, tumor cell nests or nodules may be found under the form of seminoma, Sertoli cell tumor and Leydig cell tumor, sometimes these cells are mixed, forming together a neoplastic nodule.

Rare primary tumors are rarely diagnosed in the testis, but fibromas and fibrosarcomas, hemangiomas and hemangiosarcomas can be mentioned. Leiomyoma has been reported in the vaginal sheath in dogs [36] and in the paratesticular region in stallions [18].

Embryonal carcinoma is a poorly differentiated epithelial tumor, originating in undifferentiated embryonic cells. Histologically, tumor cells with solid or papilliferous adenocarcinomatous growth can be identified. For diagnostic and differential diagnostic purposes, the reaction for the demonstration of the presence of alpha-fetoprotein in epithelial cells is used [20].

Gonadoblastoma can appear in testes or ovaries with normal differentiation, while in humans it occurs in young patients who are phenotypically of female sex, having a complementary male chromosome and anatomical intersexuality. This rare tumor has a solid aspect, and microscopically, it is a mixture of germ cells, small epithelial cells similar to Sertoli cells, granulosa cell-like cells and interstitial acidophilic cluster cells [20].

Adenoma and adenocarcinoma are tumors originating in the rete testis that have been described in dogs and horses. Structure is tubulopapillary, with reduced stroma. Cells are small, enclosed in nests with scant cytoplasm, arranged in multiple rows. In mice, rete testis adenocarcinoma can be induced with diethylstilbestrol, injected in gestating mice. Adenocarcinomas of papilliferous type microscopically occur [28].

Tumors metastatic to the testis are uncommon in all species.

Tumors of the testicular adnexal structures (epididymis, spermatic cord, capsule, and supporting structures) are very infrequent in domestic animals. Carcinomas of the epididymis have been reported in the dog and bull.

Mesotheliomas can develop in the serosa of the pleural or peritoneal cavities, but some appear to develop as primary tumors within the scrotal sac. These tumors can be difficult to distinguish from metastatic carcinomas, and immunohistochemical staining is helpful. Mesotheliomas are distinctive in that they co express intermediate filament proteins, vimentin and cytokeratin [51].

Miscellaneous tumors of the testis and adnexa. Fibromatous, vascular, smooth muscle, mast cell tumors, and schwannomas have been reported to develop in the testes. They are rare, and they do not differ from their counterparts elsewhere; see the fascicle on mesenchymal tumors of skin and soft tissue in this series [51].

Tumor-like lesions of the epididymis. Adenomyosis of the epididymis, the extension of the lining epithelium into the muscle of the epididymal ducts. Adenomyosis occurs in aged bulls and frequently in dogs with Sertoli cell tumors, and has been produced experimentally in dogs by estrogen administration. It also occurs in stallions, rams, and bucks [51].

12.2. TUMORS OF ACCESSORY REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

Squamous metaplastic changes in the epithelium of the accessory glands result from hyperestrogenism. Grazing on certain highly estrogenic clover pastures produces squamous metaplasia and cystic enlargement of bulbourethral and prostate glands in wethers. In the dog, squamous metaplasia of the prostate regularly develops in association with estrogen-producing Sertoli cell tumors of the testicle.

12.2.1. Tumors and tumorlike lesions of the canine prostate

Prostate tumors are found especially in dogs, with a higher incidence at ages ranging between 6 and 15 years, and a mean age of 10 years. In dogs, prostate hyperplasia is not followed by neoplastic proliferation. Malignant prostate tumors are associated with imbalances in the sex hormone status, but they are not associated with testicular neoplasms.

Epidemiologically, based on our data, prostate tumors have been diagnosed in 2.12% of a total number of 329 male dogs, with ages ranging between 10 and 18 years, large breeds being predominantly affected. Similar aspects are reported by the literature [20, 25]. The absolute weight of the prostate increases with age, the values found by us ranging between 10 g and 124 g, and the gland weight to body weight ratio shows values from 0.058% in a 9-year-old Caniche, up to 0.400% in a 12-year-old German Shepherd, and 0.480% in an 11-year-old Airedale Terrier. The study was performed in 20 necropsied dogs, diagnosed with different disorders.

Prostate tumors in dogs induce clinical signs manifesting by difficulty in raising the posterior limbs, weight loss with marked amyotrophy, difficulties to urinate and defecate. Rectal touch and the palpation of the prostate, supplemented by radiographic examination, show an abnormal aspect of the prostate (increased volume, bosselated aspect, dense, fibrous or even bone consistency).

Prostate tumor metastases are estimated at 70–80% of cases, with more frequent locations in iliac lymph nodes, then in the lungs, urinary bladder, mesentery, rectum and bones (pelvis, femur and posterior vertebrae).

Compared to what is known in human oncology, some parallels can be established, such as advanced age and metastases, approximately with the same locations, especially in bone, as well as regarding histological aspects that are almost identical in dogs and humans. The progress made over the past years regarding the early diagnosis of prostate neoplasms in humans has determined a decrease in the incidence of mortality and the prolongation of life expectancy in men. Thus, the systematic dosage of the prostate antigen, in men over 50 years of age, in the case of a concentration of over 3 μg/l, associated with transrectal ultrasonography, detects prostate neoplasms at an early stage, in which surgery has maximal effect [19]. Numerous factors are involved in the control of prostate cell growth. Thus, the paracrine interaction between the different prostate cells that involve steroid hormones and growth factors is known. These interactions influence the hormone dependent growth of prostate cancer cells and they probably play a role in the mechanisms that favor the appearance of hormone dependent tumors [5]. The authors estimate that the elucidation of these mechanisms and their role in the expression of certain oncogenes allows for the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic methods of prostate cancer. It is more and more obvious that sex hormones, but also certain growth factors, their receptors and oncogenes play a role in the development of prostate pathology. The studies performed over the past years on the relationships between the stroma and prostate epithelium, for the identification of growth factors and their receptors, as well as on the expression of oncogenes and suppressor genes, have determined the appearance of new hypotheses and new mechanisms for the explanation of the growth of normal and abnormal prostate cells. Statistics report that the incidence of benign prostate hyperplasia and cancer is alarmingly increasing in industrialized countries; thus, between 50 and 80 years, 50% up to 90% of men develop prostate hyperplasia and 30% of these undergo surgery [5].

The classification of prostate tumors in animals considers almost exclusively the canine species [5]:

- adenocarcinoma: alveolar papillary type; acinar and organoid type;

- poorly differentiated carcinoma;

- benign mesenchymal tumors: leiomyoma and fibroma;

- sarcoma;

- unclassified tumors;

- secondary tumors;

- tumorlike lesions: acinar hyperplasia; squamous metaplasia and cysts.

12.2.1.1. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate

Prostate adenocarcinomas in dogs have an insidious evolution with high malignancy. Etiology cannot be defined with certainty, since they have been observed following castration, so testosterone does not influence the appearance and evolution of prostate carcinoma. In a study performed by BELL et al. (1991) in castrated and non-castrated dogs, the authors conclude that the risk for prostate tumors is 2.38-fold higher for castrated subjects, similar results being reported by other authors [12, 32, 48].

Clinical manifestations have no specificity, being similar to other prostate disorders. In the case of prostate adenocarcinomas, the emaciation of muscle masses and locomotion disorders can appear, determined especially by metastases in the lumbar vertebrae, pelvic vessels and sometimes in the long bones of posterior limbs. Metastases can also appear in other bones, such as the shoulder, ribs and phalanges. The above mentioned authors report the following incidence of metastases in different organs and tissues: lung 62%, all subjects being castrated; liver 33%; regional lymph nodes 33%; spleen 26%; colon/rectum 22%; urethra 18%; urinary bladder 18%; heart 18%; kidney 18%; adrenal gland 11%.

Macroscopically, the increase in volume of the prostate in the case of carcinoma is little probable, the asymmetrical aspect and the irregular surface being more frequently found in benign hyperplasia. In section, the gland has a fibrous, dense aspect, with frequent ossification foci.

Microscopically, adenocarcinoma develops from duct or acinar epithelium. Prostate adenocarcinomas can be histologically differentiated into types, the following forms developing in dogs, according to LEAN and LING (1968): the intraalveolar proliferation type; the small acinar type, the syncytial type; the discrete epithelial type; the poorly differentiated type. According to HALL et al. (1976), microscopic structure can differentiate the following types: the alveolar papillary type; the acinar type; the organoid rosette type; the poorly differentiated type.

The microscopic structure of prostate adenocarcinoma shows an active participation of the mesenchyme, along with neoplastic epithelial proliferations. The neoplasm, invades both the prostate capsule and adjacent tissues with the presence of epithelial cells and plasmacytes, less of lymphocytes, in the mesenchymal tissue. In areas with more abundant stroma, muscle fibers are identified.

The alveolar papillary type is characterized by round or oval cells, which develop on a fine connective framework in the lumen of glandular alveoli. The cytoplasm of neoplastic cells is abundant, frequently granular or eosinophilic, containing bullae that dislocate the nucleus and confer a signet ring cell aspect; the material contained is alcian blue and PAS-positive. Protein formations under the form of drops can be identified in the nucleus. Nuclei are round to oval, frequently prismatic, with chromatin condensation, having one or two nucleoli. Multiple nodules of alveolar shape, with neoplastic cells that proliferate from the basal membrane and fill the lumen, may be identified in the tumor mass. An important aspect in differential diagnosis from benign hyperplasia consists in the fact that neoplastic cells developed under the form of fern or palm leaves do not lie on a basal membrane (Fig. 29).

Fig. 12.29

Prostate carcinoma, metastasis in spleen.

The acinar type usually develops as cell proliferations arranged in acini in a fibromuscular mass, which confers the scirrhous tumor aspect. Acinar cells are small and have different anaplastic degrees. Papillary proliferations in the acinar lumen may be present. Epithelium is usually structured in one or two layers, and isolated groups of neoplastic cells can be found in the mesenchymal mass. Mucus deposits may be detected in the acinar lumen.

A particular aspect of the acinar type development is the presence of syncytial cells, along with pleomorphic fusiform cells, arranged in nests, similarly to sarcoma.

The organoid type, with the arrangement of cells in rosettes, has an obviously alveolar structure. Cells arranged in a rosette pattern have basal nuclei and form compact masses. Usually, cells are small and of cuboid to columnar shape, with oval cytoplasm, with nuclei that have one or two nucleoli. Frequent necroses are found in the central portion of the tumor mass. Compared to other prostate neoplastic forms, in this type the mesenchyme is more poorly represented (Fig. 12.26).

Fig. 12.26

Organoid carcinoma, with rossette formation, prostate.

Poorly differentiated carcinoma has a marked malignant character, with groups of neoplastic cells disseminated in a fibromuscular mass, under the form of isolated cells, syncytialized cells, compact groups or deformed cells.

Fusiform cells with sarcomatous aspect or round cells with hyperchromatic nuclei or vesicular nuclei can appear.

The presence of giant cells, mitoses and the invasion of lymph nodes, venules, as well as perineuronal infiltration prove a high malignancy character (Fig. 12.23–12.25, 12.27, 12.28).

Fig. 12.23

Poorly differentiated carcinoma, prostate.

Fig. 12.24

Poorly differentiated carcinoma, prostate.

Fig. 12.25

Acinar carcinoma scirrhous with fibromuscular stroma, prostrate.

Fig. 12.27

Anaplastic carcinoma of prostate

Fig. 12.28

Poorly differentiated carcinoma, prostate.

12.2.1.2. Mesenchymal tumors

The more frequently diagnosed primary mesenchymal tumors are: leiomyoma, fibroma, fibrosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma.

Leiomyoma has been relatively frequently diagnosed. This benign tumor develops under a nodular form in the fibromatous tissue mass, having the known biological characteristics of leiomyoma.

Fibroma has been rarely diagnosed, and it can accompany some forms of adenocarcinoma.

Sarcomas are reported by the literature, being described as fibrosarcomas and leiomyosarcomas.

12.2.1.3. Tumors metastatic to the prostate

Prostate metastases of neoplasms developed in other organs or tissues are rare. Infiltrations of lymphoreticular structures have been reported in bulls, dogs and cats. Lymphomatous infiltrations are difficult to differentiate from lymphocytic infiltrations that are usually found in old subjects.

Carcinomas developed in the urinary bladder, especially at the level of the prostate, may extend and invade the gland, being identified in different species.

12.2.1.4. Tumorlike lesions

Acinar hyperplasia

Prostatic hyperplasia/hypertrophy is frequently found in dogs and extremely sporadically in bulls. In dogs, the age with the highest incidence is 4–5 years, with an 80% frequency, especially in adult and old dogs.

Macroscopically, the whole gland or one of the lobes is increased in volume, and sometimes nodules appear that are prominent on the surface of the gland, venous or lymphatic vascularization being obvious. On palpation, cysts are fluctuant, in a dense connective tissue mass. In section, the gland is spongy, with cysts of various sizes, with a liquid, mucous or gelatinous content, milky aspect, non-uniform dissemination, some of them being subcapsular, and others in the gland mass. The urethra in the prostate region appears visibly narrowed, with yellowish mucosa and obvious papillae.

Microscopically, a complex structure, adenoid hyperplasia, stromal hyperplasia, condensations and various cystic formations are found. Adenoid and acinar hyperplasia consists of epithelial hyperplasia and hypertrophy with papillary proliferations in the lumen, lying on the basal membrane. Structure is lobular, with the acinar arrangement of epithelium, cystic formations of various sizes, inflammatory monocyte infiltration in the interstitium (Fig. 12.31). The diagnosis of prostatic hypertrophy is difficult due to the resemblance to the normal gland or chronic inflammatory processes.

Fig. 12.31

Benign prostate hyperplasia.

Cysts

Cystic formations are relatively frequent in old dogs, associated with chronic inflammations and/or acinar hyperplasia. Cysts develop from acini, being delimited by fibrous tissue (Fig. 12.32). Cysts represent 5% of prostate pathology, and they may occur: through the retention of secretion due to the obstruction of secretory ducts (infections, proliferations, etc.); under the form of paraprostatic cysts, independent from the gland parenchyma, whose origin is debatable; as cystic hyperplasia that develops in the gland parenchyma, providing a spongy aspect [50]. Large dog breeds are in particular predisposed, manifesting urinary disturbances (incontinence, dysuria, anuria), rectal tenesmus and abdominal distension. The cited authors recommend surgery by resection, but puncture associated with castration leads to the best results [52].

Fig. 12.32

Prostatic cysts in limpho-plasmacytic inflammation.

Squamous metaplasia

Squamous metaplasia is frequently found in dogs in association with functional Sertoli cell tumors or following estrogen administration. Metaplastic changes occur in the gland acini, more frequently in the proximity of the urethra and in the excretory ducts. The lesion has also been detected in bulls that have consumed plants containing estrogenic principles, associated with hypovitaminosis A [15].

Squamous metaplasia is produced in acini and excretory ducts, being associated with cystic dilations, neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, and the proliferation and thickening of basal membranes. Lesions similar to those of dogs have been found in boars and cats.

Differential diagnosis from squamous cell carcinoma is required.

The diagnosis of prostate disorders in dogs can be made by the cytologic examination of the prostatic fluid obtained by massage [13]. The histological examination of prostate biopsy can bring clarifications regarding differential diagnosis, by assessing the position of nucleoli. Thus, in the case of typical and atypical hyperplasia, nucleoli are located in the center of the nucleus; in moderate hyperplasia, nucleoli have an intermediate position; in severe and malignant atypical hyperplasia, the proportion of peripheral nucleoli increases from 13 to 84% in histopathological preparations, and from 40 to 92% in cytologic smears [16]. The other known and unknown elements of the malignant process should also be taken into consideration in the establishment of diagnosis and implicitly, prognosis.

12.2.2. Experimental tumors

Given the interest in human pathology, prostatic neoplasms were and still are in the focus of researchers. Their experimental induction is attempted, in order to elucidate the mechanisms of their onset, evolution and metastasis, but also their prevention and treatment.

Experiments performed in rats with intravenous methylnitrosourea administration and subcutaneous testosterone propionate implant, at 2 month interval, have determined the development of prostate adenocarcinomas in approximately 90% of cases, at 11 months [39, 40, 41]. The mentioned authors have experimentally demonstrated that methylnitrosourea is an initiator, and testosterone is a promotor of prostate tumorigenesis. In this way, BEREMBLUM’s theory (1978) that endogenous hormones could function as promoting agents, while ecological factors act as spontaneous initiators is demonstrated. Spontaneous initiators remain to be identified for each cancer type, which would facilitate the attenuation or even cessation of their role.

The repeated administration of cadmium chloride injections causes severe ultrastructural changes in the prostate epithelium. Changes in cell organelles, the rough endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and especially in the nucleus, are detected. Cells that infiltrate the stroma contain secretory vacuoles and their nuclear invaginations are similar to ultrastructural pathological forms found in humans. Following oral cadmium chloride administration, severe dysplastic changes appear, without the evidencing of carcinoma-like aspects. HOFFMANN et al. (1988) identify in the cadmium-exposed rat prostate histopathological and ultrastructural similarities to pathological aspects of human prostate neoplasm. Thus, following cadmium administration in rats, deep epithelial changes occur, with the destruction of structural differentiation. This suggests that atypical hyperplasia and dysplasia should be regarded as potentially preneoplastic lesions.

Cadmium-induced carcinomatous cells are similar, through their ultrastructural pathological characteristics, to human prostate carcinoma, especially type I and IV carcinoma. The evolution of cells that infiltrate the stroma by cytoplasmic processes, secretory amoeboid vacuoles and nuclear evaginations is similar to ultrastructural observations in man. The carcinogenic action of cadmium chloride on the rat prostate epithelium should be interpreted cautiously, given the peculiarities of the human species, and especially the specificity of cancer for each individual.

Experimental studies in rats have investigated the long-term effects of castration on the proliferative activity of the basal and secretory epithelial cells of the prostate. Castration induces a high apoptosis percentage in secretory cells, without the compensating hyperplasia of basal cells. Ultrastructurally, after castration, a quiet state of both basal and secretory cells occurs. The proliferative potential of secretory cells is not diminished three months after castration [10,11].

EATON and PIERREPOIN (1988) demonstrate that neoplastic epithelial cells from spontaneous prostate carcinoma in dogs can be maintained and grown in cell cultures and xenografted in athymic mice. An epithelial cell line (CPA-1) was isolated from primary cultures and was partially stabilized in vitro. Androgens and estrogens did not change the growth of this cell line, and the high affinity of receptors for these steroids has not yet been demonstrated for these cells. Xenografts were serially transferable, during life, in both sexes. Androgen and estrogen receptors could not be detected in the homogenates of xenografts or of the primary tumor.

The histological aspects in serial transplanted tumors and in xenografts generated by the inoculation of the cell line (CPA-1) and the different cloning of the substrate were highly similar to those of the primary tumor, being well differentiated.

12.3. TUMORS OF THE PENIS

The main tumors of the penis and prepuce are: transmissible fibropapilloma of the bull; squamous cell papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma of the horse; canine transmissible venereal tumor; squamous cell carcinoma of the penis and prepuce.

12.3.1. Fibropapilloma of cattle

Fibropapilloma in bulls is induced by type 2 fibropapilloma virus, located in the penile mucosa. The tumor is more common in young bulls, aged between 1 and 2 years, having an endemic character in some fattening houses, and it can also occur in breeding bulls.

Macroscopically, tumors appear as single or multiple formations, from 0.5 cm to several cm (10–15 cm) in diameter. They have a pink or white-gray color, consistency is dense, fibrous, and well vascularized fibrous tissue covered with epithelium appears in section. The tumor adheres by a short thick pedicle, in most cases having a large implantation base. The rich vascularization and traumas cause bleeding wounds and infections.

Microscopically, in young forms with rapid evolution, especially in young bulls, an intensely cellularized connective structure appears, with numerous fibroblasts arranged in bundles, and capillaries, with the occasional presence of rich monocyte infiltration and mitoses. In chronic evolution forms, especially in adult breeding bulls, the tumor is predominantly fibrous, poorly cellularized and vascularized, with thick collagen fibers (Fig. 12.1–12.3).

Fig. 12.1

Fibropapiloma of the penis, bull.

Fig. 12.2

Fibropapiloma of the penis, bull.

Fig. 12.3

Fibropapiloma of the penis, bull.

The development of fibropapilloma can determine compressions and the narrowing of the urethra; or it can induce phimosis or paraphimosis. Because the tumor is well vascularized, surgery is difficult; sometimes other small tumors occur, but spontaneous regressions have also been noted [52].

12.3.2. Transmissible genital papilloma of pigs

Transmissible genital papilloma has been found in swine, its viral etiology being demonstrated. The tumor is small, round, slightly projecting on the mucosal surface, reaching 3 cm in diameter. Papilloma can regress in time. Histologically, it is characterized by the excessive thickening of the spinous layer, moderate connective tissue proliferation, and epithelium is covered with a thin layer of keratinized cells [20]. Large spherical, acidophilic inclusion bodies are present in the cytoplasm of scattered cells [51].

12.3.3. Transmissible venereal tumors

Transmissible venereal tumors are found in dogs, being located in the penis and/or prepuce in males, and on the vulvar and vestibular mucosa in females. These tumors have an endemic evolution in certain geographical areas, being transmissible by cells, both by mating and experimentally, by cell inoculation. The disease has been reported on all continents. No breed, age or sex sensitivity has been reported; in contrast, the breeding system, agglomeration and unsupervised contact are factors that favor the transmission of the disease [2].

Extragenital locations such as in the nasal, oral and ocular mucosa, have been found. Thus, PARENT et al. (1983) present three cases of nasal location of the venereal tumor and the need for differential diagnosis from other nasal mucosal tumors.

Clinically, in both males and females, the disease starts with pruritus, mucosal inflammation and the appearance of small gray granulations that change into red nodules. These become confluent, forming single or multiple nodules [26].

Macroscopically, tumor proliferation can be single or multiple, sessile or pedunculated, nodular or papillary, having a firm consistency, with sizes of up to 15 cm in diameter [23].

Histologically, tumor cells are uniformly round, ovoid or slightly polyhedral, with large, round, vesicular nuclei and obvious nucleoli. Mitotic forms are frequent, and the epithelial surface is frequently hyperplastic and ulcerated. A fine connective stroma is found in the tumor structure, with numerous capillaries. The tumor is intensely cellularized. Cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm, and lymphocytes, plasmacytes and few eosinophils are identified among tumor cells. The general image is that of round cell sarcoma (Fig. 12.4–12.7).

Fig. 12.4

Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

Fig. 12.5

Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

Fig. 12.6

Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

Fig. 12.7

Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

Metastases are rare, they can be found in inguinal lymph nodes and in various organs (liver, kidney, bone, etc.), and recurrences are not uncommon [15, 20]. Following experimental inoculation with cancer cells in young puppies aged 13 days - 3 weeks, subdural or spinal epidural metastases have been found at the level of the cerebellum [34, 38].

Electron microscopy shows the degeneration of cytoplasmic organelles, viral type inclusions being identified [4, 23]. The neoplasm could not be transmitted by acellular tumor filtrate. A noteworthy aspect is the experiment performed by OKAMOTO et al. (1998) by the culture of cells from canine transmissible sarcoma, the authors obtaining two cell types, one type of cells non-adherent to one another, with changing aspect, and another adherent type. Following histological examination and karyotype analysis, non-adherent (changing) cells were catalogued as transmissible sarcoma cells, and adherent cells were determined to be fibroblasts. After the experimental implantation of non-adherent cells, transmissible sarcoma was reproduced in 3 dogs, while the adherent cell implantation did not result in tumor development.

The treatment of transmissible sarcoma by surgical methods is not satisfactory, which has led to the experimenting of other procedures. Thus, following the castration of females with transmissible sarcoma, the relatively rapid regression of neoplasms was found, within 14 days [27]. Chemotherapy had good results: vincristine sulfate administered 0.025 mg/kg intravenously, weekly, for 3 weeks, resulted in no recurrences in 23 of 24 dogs, after 2 years. Combined treatment: cyclophosphamide (1 × 50 mg tablet/day) with methotrexate (0.35 mg/kg, intravenously, weekly) and vincristine sulfate (0.013 mg/kg, intravenously, weekly) led to particularly good results [6, 7]. BCG use was effective, resulting in complete tumor regression [26].

12.3.4. Squamous cell papilloma

Squamous cell papilloma is a benign tumor, being found in horses, more rarely in other species. Microscopically, it has a papilliform aspect, with intensely keratinized epithelium, small sizes, large attachment base and necrosed surface. Microscopically, epithelium is keratinized, with fibrous stroma, infiltrated with lymphoplasmacytic cells.

12.3.5. Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis and prepuce is found in horses, dogs and bulls. In the horse, the neoplasm is equally found in stallions and geldings, and is located in particular in the glans. Neoplasms are frequently ulcerated and necrosed. The tumor is more common in old subjects, and is associated with smegma accumulation.

Histologically, tumors are differentiated and keratinized, with the aspect characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor proliferation presents infiltration with inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils, it is delimited, with frequent necrotic and calcification foci. The tumor has infiltrative growth towards the corpus cavernosum, with metastases in inguinal lymph nodes and frequently in organs such as the lung and liver (Fig. 12.8).

Fig. 12.8

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, horse.

In dogs, squamous cell carcinoma located in the penis or prepuce is similar to horse neoplasm, but keratinization is poor or absent. Metastases are present in over 25% of cases, usually in inguinal lymph nodes [37, 52].

Squamous cell carcinoma requires differential diagnosis from squamous cell papilloma [51].

Other mesenchymal tumors located in the penis and/or prepuce with a lower incidence are: fibrosarcoma, diagnosed in bulls, horses and dogs; lymphoma, more frequent in bulls, dogs, boars and cats; hemangioma and hemangiosarcoma.

Tumor-like lesions are in the first place granulomas produced by Habronema larvae. These granulomas appear as irregular red nodules, located in the proximity of the urethral process of stallions. Microscopically, the lesion has the character of a parasitic granuloma, having caseification necrosis in the center, then cell infiltration with eosinophils, histiocytes and lymphocytes, and peripherally, fibrosis. In most lesions, Habronema larvae are identified.

Fig. 12.22

Benign hyperplasia, prostate.

Fig. 12.30

Prostate carcinoma, metastasis in kidney.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.

- Baba AI, Cătoi C, Prică A, Fârtan S. Aspecte morfopatologice ale tumorilor de prostată la câine. Simpozion Act. Patol. Anim. Dom., Cluj-Napoca. 1997:347.

- 2.

- Batamuzi EK, Kassuku AA, Agger JF. Risk factors associated with canine transmissible venereal tumour in Tanzania. Prev. Vet. Med. 1992;13 (1):13–17.

- 3.

- Bell FW, Klausner JS, Hayden DW, Feeney DA, Johnston SD. Clinical and pathologic features of prostatic adenocarcinoma in sexually intact and castrated dogs: 31 cases (1970–1987). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1991;199 (11):1623–1630. [PubMed: 1778750]

- 4.

- Cabanie P, Vanhaverbeke G, Magnol JP. Etude ultrastructurale du Sarcome de Sticker du Chien à différents stades de son evolution. Revue Méd. Vét. 1973;124:1237–1253.

- 5.

- Chevalier S, McKercher G, Chapdelaine A. Hyperplasic bénigne et cancer de la prostate: hormones steroïdiennes et facteurs de croissance. Médecine Sciences. 1993;9:542–546.

- 6.

- Das U, Das AK, Das D, Das BB. Clinical report on the efficacy of chemotherapy in canine transmissible venereal sarcoma. Ind. Vet. J. 1991;68(3):249–252.

- 7.

- Das AK, Das U, Das D. A chemical report on the efficacy of vincristine on canine transmissible venereal sarcoma. Ind. Vet. J. 1991;68(6):575–576.

- 8.

- Eaton CL, Pierrepoint CG. Growth of a Spontaneous Canine Prostatic Adenocarcinoma In vivo and In vitro: Isolation and Characterization of a Neoplasic Prostatic Epithelial Cell Line, CPA-1. The Prostate. 1988;12:129–143. [PubMed: 3368402]

- 9.

- Edwards DF. Bone Marrow Hypoplasia in a Feminized Dog with a Sertoli Cell Tumor. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1981;178 (5):494–496. [PubMed: 7240009]

- 10.

- Evans GS, Chandler JA. Cell proliferation Studies in the Rat Prostate. I. The Effects of Castration and Androgen Induced regeneration Upon Basal and secretory Cell Proliferation. The Prostate. 1987a;11:339–351. [PubMed: 3684785]

- 11.

- Evans GS, Chandler JA. Cell proliferation Studies in the Rat Prostate. I. The proliferative role of basal and secretory cells during normal growth. The Prostate. 1987b;10:163–167. [PubMed: 3562347]

- 12.

- Evans JE, Zontine W Jr, Gran E Jr. Prostatic adenocarcinoma in a castrated dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1991;186:78–80. [PubMed: 3965432]

- 13.

- Gandini C, Capurro C. Indagine citologica su prelievi effetuati mediante massagio ghindolare per la diagnosi delle affezioni prostatiche del cane. Veterinaria (Cremona). 1991;5(3):69–74.

- 14.

- Gelberg HB, McEntee K. Equine testicular interstitial cell tumors. Vet. Pathol. 1987;24:231–234. [PubMed: 2885961]

- 15.

- Hall WC, Nielsen SW, McEntee K. Tumours of the prostate and penis. Bull World Health Organ; 1976. pp. 53pp. 247–256. [PMC free article: PMC2366510] [PubMed: 1086155]

- 16.

- Helpap B. Observations on the number, size and localisation of nucleoli in hyperplastic and neoplastic prostate disease. Histopathol. 1988;13:203–211. [PubMed: 2459042]

- 17.

- Hoffmann L, Putzke HP, Bendel L, Erdmann T, Huckstorf C. Electron microscopic results on the ventral prostate of the rat after CdCl2 administration. A contribution towards etiology of the cancer of the prostate. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1988;114:273–278. [PubMed: 2454927]

- 18.

- Johnson RC, Steinberg H. Leiomyoma of the Tunica Albuginea in a Horse. J. Comp. Pathol. 1989;100:465–468. [PubMed: 2760279]

- 19.

- Labrie F. Strategic efficace et peu coûteuse pour la détection du cancer de la prostate à un stade précoce alors que la guérison est possible. Médecine sciences. 1992;8:703–706.

- 20.

- Ladds PW. The Male Genital System. In: Jubb, Kennedy, Palmer, editors. Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 3. Academic press; New-York: 1993. pp. 471–529.

- 21.

- Laging C, Kröning T. Beobachtungen zum Űbertragbaren Venerischen Tumor (Sticker) beim Hund. Tieräztliche Praxis. 1989;17(1):85–87. [PubMed: 2470163]

- 22.

- Lipowitz AJ, Schawartz A, Wilson GR, Ebert JW. Testicular neoplasms and concomitant clinical change in the dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1973;63 (12):1364–1368. [PubMed: 4760082]

- 23.

- Lombard J, Cabanie P. Le sarcome de Sticker. Revue Méd. Vét. 1968;110:565–586.

- 24.

- Mabara S, Hashimoto N, Kadote K. J. Comp. Pathol. 1990;103 (4):369–378. [PubMed: 2079552]

- 25.

- Madewell BR, Theilen GH. Tumors of the genital system. In: Theile, Madewell, editors. Veterinary Cancer Medicine. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1987. pp. 583–600.

- 26.

- Madiot GC. Traitement medico-chirurgical du Sarcome de Sticker. Thèse: École Nationale Vétérinaire de Toulouse; 1980.

- 27.

- Nandi SN, Nayak NC, Som TL. Effect of ovariectomy on regression of transmissible venereal tumour in bitches. Ind. J. Vet. Path. 1988;12:97–98.

- 28.

- Newbold RA, Bullock BC, McLachlan JA. Adenocarcinoma of the Rete Testis. Diethylstilbestrol Induced Lesions of the Mouse Rete Testis. Am. J. Path. 1986;125 (3):625–628. [PMC free article: PMC1888460] [PubMed: 3799821]

- 29.

- Nielsen SW, Lein DH. Tumours of the Testis. Bull. Wld. Hlth. Org. 1974;50:71–78. [PMC free article: PMC2481218] [PubMed: 4547653]

- 30.

- Nieto JM, Pizarro M, Fontaine JJ. Tumeurs testiculaires du chien. Rec. Med. Vet. 1989;165(5):449–453.

- 31.

- Obradovich J, Walshaw R, Goullanud E. The influence of castration on the development of prostatic carcinoma in the dog. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1987;1:183–187. [PubMed: 3506104]

- 32.

- Okamoto Y, Fujinaga T, Tajima M, Hoshi N, Otomo K, Koike T. Isolation and Cultivation of Canine Transmissible Sarcoma Cells. Jpn. J. Vet. Sci. 1988;50(1):9–13. [PubMed: 3361737]

- 33.

- O’Keefe DA. Tumors of the Genital System and Mammary Glands. In: Ettinger, Feldman, editors. Veterinary Internal Medicine. Vol. 2. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia: 1995. pp. 1699–1704.

- 34.

- Padovan D, Yang T, Fenton MA. Epidural spinal metastasis of canine transmissible venereal sarcoma. J. Vet. Med. A. 1987;34:401–404. [PubMed: 3113123]

- 35.

- Parent R, Teuscher E, Morin M, Buyschaert A. Presence of the canine Transmissible Veneral Tumor in the Nasal Cavity in the Area of Dakar (Senegal). Can. Vet. J. 1983;24:287–288. [PMC free article: PMC1790422] [PubMed: 17422304]

- 36.

- Patnaik AK, Liu SK. Leiomyoma of the tunica vaginalis in a dog. Cornell Vet. 1974;65:228–231. [PubMed: 1126170]

- 37.

- Patnaik AK, Matthiesen DT, Zarvie DA. Two cases of canine penile neoplasm: Squamous cell carcinoma and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 1987;24:403–406.

- 38.

- Placke ME, Hill DL, Yang TJ. Cranial metastasis of canine transmissible venereal sarcoma. J. Vet. Med., A. 1987;34:125–132. [PubMed: 3109161]

- 39.

- Pollard M, Luckert PH, Schimidt MA. Induction of prostate adenocarcinomas in Lobund-Wistar rats by testosterone. Prostate. 1982;3:563–568. [PubMed: 7155989]

- 40.

- Pollard M, Luckert PH. Production of autochthonous prostate cancer in Lobund-Wistar rats by treatments with N-nitroso-N-methylurea and testosterone. J. Notl. Cancer Inst. 1986;77:583–587. [PubMed: 3461217]

- 41.

- Pollard MH, Luckert P, Snyder DL. The promotional effect of testosterone on induction of prostate cancer in MNU-sensitized L-wrots. Cancer Letters. 1989;45:209–212. [PubMed: 2731164]

- 42.

- Prange H, Kosmehl H, Katenkamp D. Die Pathologie der Hodentumoren des Hundes. 2. Morphologie und Vergleichen-morphologische Aspekte. Arch. Exper. Vet. Med. 1987;41:366–388. [PubMed: 2820337]

- 43.

- Reif JS, Maguire TG, Kennedy RM, Bodey RS. A cohort study of canine testicular neoplasia. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1979;175:719–723. [PubMed: 43317]

- 44.

- Sanford SE, Miller RB, Hoover DM. A light and electron microscopical study of intranuclear cytoplasmic invaginations in interstitial cell tumours of dogs. J. Comp. Pathol. 1987;97:629–635. [PubMed: 3443687]

- 45.

- Sherding RG, Wilson GP, Kociba GJ. Bone Marrow Hypoplasia in Eight Dogs with Sertoli Cell Tumor. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1981;178 (5):497–501. [PubMed: 6113231]

- 46.

- Taylor PA. Prostatic adenocarcinoma in a dog and a summary often cases. Can. Vet., J. 1973;14:162–166. [PMC free article: PMC1696161] [PubMed: 4727322]

- 47.

- Wakui S, Furusato M, Nomura Y, Iimori M, Kano Y, Aizawa S, Ushigome S. Testicular Epidermoid Cyst and Penile Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a dog. Vet. Pathol. 1992;29:543–545. [PubMed: 1448902]

- 48.

- Weaver AD. Fifteen cases of prostatic carcinoma in the dog. Vet. Rec. 1981;109:71–75. [PubMed: 7292934]

- 49.

- Weaver AD. Survey with follow-up of 67 dogs with testicular sertoli cell tumours. Vet. Rec. 1983;113:105–107. [PubMed: 6137897]

- 50.

- White RAS, Hertage ME, Dennis R. The diagnosis and management of paraprostatic and prostatic retention cysts in the dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1987;28:551–574.

- 51.

- Kennedy PC, Cullen JM, Edwards JF, Goldschmidt MH, Larsen S, Munson L, Nielsen S. Histological Classification of Tumors of the Genital System of Domestic Animals. Second Series. IV. WHO, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Washington, D.C: 1998.

- 52.

- Baba AI. Oncologie comparată. Acad. Române; Bucureşti: 2002.

List of Figures 12.1-12.32

- Fig. 12.4 Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

- Fig. 12.5 Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

- Fig. 12.6 Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

- Fig. 12.7 Transmissible veneral tumor, dog.

- Fig. 12.10 Intratubular seminoma.

- Fig. 12.11 Diffuse seminoma with starr-sky appearance.

- Fig. 12.12 Diffuse seminoma with giant cells.

- Fig. 12.13 Intratubular Sertoli cells tumor.

- Fig. 12.14 Intratubular Sertoli cells tumor.

- Fig. 12.15 Diffuse Sertoli cells tumor.

- Fig. 12.16 Diffuse Sertoli cells tumor.

- Fig. 12.17 Solid diffuse Leydig cell tumor. *)

- Fig. 12.18 Solid diffuse Leydig cell tumor. *)

- Fig. 12.19 Angiomatoid Leydig cell tumor. *)

- Fig. 12.20 Angiomatoid Leydig cell tumor. *)

- Fig. 12.21 Pseudoadenomatous Leydig cell tumor. *)

- Fig. 12.22 Benign hyperplasia, prostate.

- Fig. 12.23 Poorly differentiated carcinoma, prostate.

- Fig. 12.24 Poorly differentiated carcinoma, prostate.

- Fig. 12.25 Acinar carcinoma scirrhous with fibromuscular stroma, prostrate. *)

- Fig. 12.26 Organoid carcinoma, with rossette formation, prostate.

- Fig. 12.27 Anaplastic carcinoma of prostat.

- Fig. 12.28 Poorly differentiated carcinoma, prostate.

- Fig. 12.29 Prostate carcinoma, metastasis in spleen.

- Fig. 12.30 Prostate carcinoma, metastasis in kidney.

- Fig. 12.31 Benign prostate hyperplasia.

- Fig. 12.32 Prostatic cysts in limpho-plasmacytic inflammation.

Footnotes

- *)

Courtesy of W.H.O.

- MALE GENITAL TRACT TUMORS - Comparative OncologyMALE GENITAL TRACT TUMORS - Comparative Oncology

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...