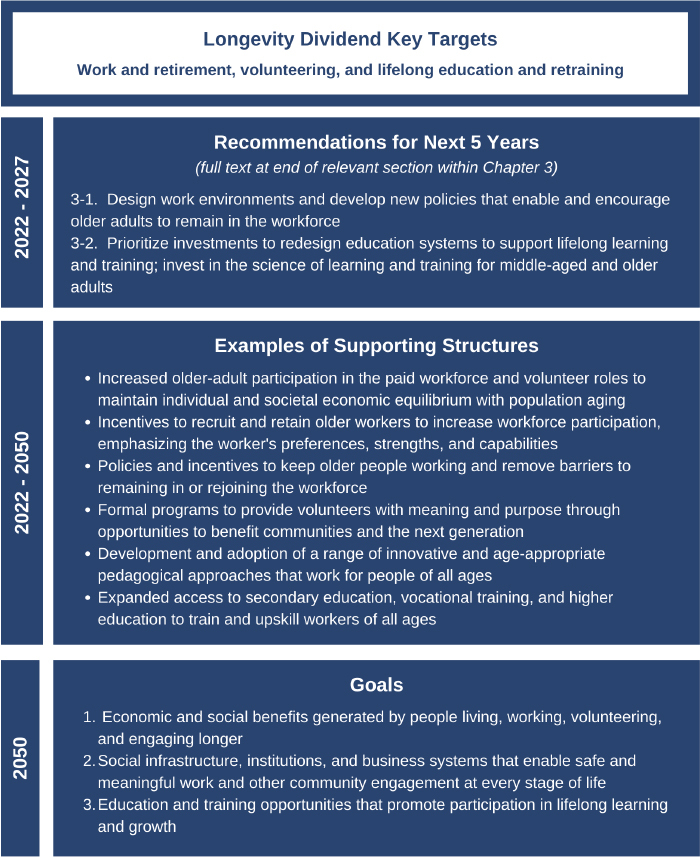

The benefits of healthy longevity are many. This chapter describes economic and fiscal benefits that societies can expect as they improve the health and well-being of people across the life course. Figure 3-1 describes components of the commission's roadmap and timeline for achieving the economic and fiscal benefits of healthy longevity. The commission asserts that the longevity dividend is possible only with action across the domains discussed in this chapter in concert with those discussed in Chapters 4, 5, and 6.

FIGURE 3-1

Longevity dividend roadmap.

INTRODUCTION

Improvements in health over the life course and fewer years spent in poor health are intrinsically valuable to people. Beyond intrinsic value, good health adds value to the economy and government coffers. When accompanied by life span increases, good health also enables people to work longer to finance their longer lives. But societies must change “how we think, act, and feel about older people and aging” (Ghebreyesus, 2021, p. 865) to reap a new and expanded longevity dividend. The anticipated longevity dividend for individuals includes an expanded period of life with good health and well-being that allows them to be productive members of society in paid and unpaid roles. With this better health and long life, most people will work longer than they do now to support the cost of their healthy, long life. The individual dividend feeds into a societal dividend with intangible benefits from social cohesion and a thriving population of old and young people, in addition to a larger economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), which feeds government coffers. A large literature in economics supports the notion that health, including health for older people, is good for economic growth.

While longevity has been increasing globally, recent gains in longevity have come with more years in poor health (see Chapter 6). If this trend continues, societies may struggle to support the health care, long-term care, housing, pension, and other needs of older people. Fortunately, as discussed in Chapters 4–6, much is known about how to increase healthy longevity. With an increase in years in good health as a proportion of the life span, older people will spend more of their years with the health they need to remain active and to engage and participate in and contribute to society in the ways they choose.

The commission envisions that older people in middle- and high-income countries may seek to remain in or re-enter the workforce, care for or support family members, volunteer, or engage in other activities for the good of society. The aim of this report is to provide a roadmap for removing barriers to and expanding options for productive engagement for everyone in all countries, especially older people.

This chapter addresses work and retirement as either/or states, but there are many paths in retirement. People move in and out of the workforce in early and middle ages (e.g., for childrearing) and as they grow older. Some have called for “an end to retirement,” not in terms of pensions or financial support but an end to the expectation that people should start work after receiving education, work for a long period, and then stop working altogether. Instead, as people need to work more years to support their longer lives, they will likely experience cycles of work, retraining, absence from the workforce, and reentry into the workforce across the life course. This view of life is described in several recent publications, including The New Map of Life (Stanford Center on Longevity, 2021) and The 100-Year Life (Gratton and Scott, 2016). Although a future of healthy longevity will require attention to work and education across the life course, this chapter focuses on the later work years.

In contrast to most key targets across this report, the key target focused on work and retirement in this chapter is less relevant to low-income countries than to high-income countries. Specifically, the commission does not suggest that low-income countries could improve healthy longevity by increasing the number of older people working because a much higher percentage of people over age 65 remain in the workforce in these countries (see Figure 3-4). Rather, in Chapter 4, the commission recognizes the importance of expanding access to pensions for low-income older people across countries, which could enable a period without work in later years, potentially decreasing the percentage of older people in the workforce in low-income countries.

FIGURE 3-4

Labor force participation rates among those aged 65+ by country income level. SOURCE: Adapted from UN Population Division, 2018.

Demographic Change and the Economics of Healthy Longevity

To understand how to harness the economic benefits of healthy longevity, it is necessary to disentangle two forces: falling birth rates and the rise in longevity. Both are demographic transitions leading to a shift in the age structure of the world's population.1 In combination, they are increasing the number and proportion of older people. To reap the economic benefits of this shift, a society “focuses on changes in how people age and the exploitation of life-expectancy gains” (Scott et al., 2021, p. e820). Globally, aging is occurring in every country around the world, and while life expectancy is highest in the wealthiest nations, it is rising most rapidly in low- and middle-income countries. While many low-income countries currently have a large younger population, this large young cohort can be expected to become a large old cohort. Therefore, an aging society is a reality for countries across all income levels.

Countries that have seen large and rapid declines in their fertility rate (e.g., Japan, China, Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand) are witnessing a very dramatic change in their age structure. There is fear that lower-income countries that are aging rapidly may get “old before they are rich” (Heller, 2006, p. 7), meaning that they face rapid aging but do not have the well-developed social institutions needed to support older populations, including pensions, health care, and long-term care. Countries such as the United States, which have seen a more gradual decline in their fertility rate and high levels of immigration, are experiencing an aging society but at a slower rate relative to many other countries. Even in low-income countries with slow growth in the older population, the number and percentage of older people will still grow.

Measures of the Economic and Fiscal Impact of an Aging Society

The standard narrative about aging societies in both popular culture and the academic literature assumes that a rapidly aging population leads to economic decline. More older people are assumed to create a smaller labor force, larger pension and health care costs, and therefore declining rates of GDP growth and rising public debts (Aksoy et al., 2019). The “old age dependency ratio” is the percentage of the population aged 65 and over divided by the percentage of the population between ages 15 and 64. This ratio is an easy-to-use but imperfect measure of the relationship between age structure and the economy. It assumes that “old age” and “dependency” begin at age 65, a view that has been undermined by the contributions of people aged 65 and older discussed below.

The old age dependency ratio and the assumptions it drives about the economic futures of rapidly aging countries have been criticized for more than a decade, but it is still used as a main piece of evidence that population aging is an alarming and negative phenomena. Yet, using chronological age to define “old age” ignores the heterogeneity of health and life expectancy among older people (see Chapters 1 and 6) and how, over time, health status at a given age has changed and how longer lives also offer new opportunities to shift behavior. In response, alternative approaches to a simple chronological age-based dependency ratio have been developed and studied. Some consider the ratio of pensioners to total employment (Bongaarts, 2004) or the ratio of non-workers to workers (Vaupel and Loichinger, 2006). Alternatively, some have focused on prospective age based on remaining life expectancy rather than years since birth. Lutz and colleagues (2008) proposed measuring old age as the time when remaining life expectancy is 15 years or less. Later, Sanderson and Scherbov (2013, p. 676) suggested using a “characteristics approach” to prospective age that includes “life expectancy, mortality rate, and the proportion of adult person-years lived after a particular age.” Researchers who applied the prospective aging concept to populations in Central and South America found that there was not a “massive aging process” under way. Rather, the global region is not rising at the potentially catastrophic rates that the old age dependency ratio suggests (Gietel-Basten et al., 2020).

Return on Investment of Good Health

Good health has both economic and intangible value. Economists have the tools needed to calculate the value of health, and when governments determine how to prioritize spending, they often use these tools to assign value to intangible benefits, such as well-being, separate from impacts on finances or GDP. Given the importance of health, economists have developed models for assigning dollar values to the outcomes from various health treatments (e.g., chemotherapy for cancer) to inform policy makers in resource allocation. Economists most commonly use these tools to evaluate treatments for specific diseases, but they can also be used to identify the value of healthy longevity.

People generally value longer life and improvements in the quality of life associated with good health. In valuing health and longevity, the value of longer life and improved quality of life can be quantified from the perspective of value to the person (Murphy and Topel, 2006). In contrast, traditional GDP-focused economic measures underestimate the value of longevity, health, and well-being because they do not account for improvements in length or quality of life. Valuation is critical to making informed policy and financial decisions because the public sector has borne much of the cost of the health care and medical research that have been responsible for increased life span and improved quality of life.

Various researchers have estimated the value of health. Murphy and Topel (2006) estimated the value of health improvements, independent of longevity, in the United States between 1970 and 2000. They estimated that the value of health improvement to men and women in their 40s was highest at roughly USD1.2 million and USD820,000, respectively, on a per capita basis.

Adding another dimension, Scott and colleagues (2021) found that the number of years in good health has remained constant as life expectancy has risen, creating a longer period of unhealthy life. They used the value of statistical life model to calculate the monetary value of the economic gains from slowing the rate of aging and achieving longer and healthier lives based on people's willingness to pay for good health. Their results show that, while increased life expectancy is valuable, the highest value to the individual is achieved when healthy life expectancy increases to match life expectancy. The authors assert that, given current life expectancy and disease burden, slowing down aging and reducing the advent of clusters of chronic, age-related disease is currently the most important policy imperative. They estimate that delaying the onset of age-related chronic disease to achieve one more year of life expectancy and associated improvements in good health is worth USD37 trillion in present value terms for the United States alone. Furthermore, they show that the gains due to healthy longevity will increase as the population comprises a greater number of older people living longer (Scott et al., 2021).

IMPACT OF WORK AND RETIREMENT ON HEALTHY LONGEVITY

Across the life course, the quality of jobs influences healthy longevity. The commission emphasizes the need for good, safe jobs in Recommendation 3-1 (presented later in this chapter). The impacts of work and retirement on physical, cognitive, and mental health can influence whether people choose to stay in the workforce. Those impacts are heterogeneous and are influenced by lifetime earnings, education, and other factors. Painting a clear picture of the costs and benefits of work and retirement is challenging because methods used and populations studied are heterogeneous. And, as shown below, context can shift the balance between work that improves and work that worsens health.

Working Versus Not Working

Many studies show positive correlations between work and health. For example, in a U.S. study of people aged 59–69, employed participants were found to be 6 percent less likely than those who were not working to report fair or poor health, and there was a small, but statistically significant, positive impact on activities of daily living (ADLs), independent activities of daily living (IADLs), mood, and mortality. People with demanding, undesirable jobs still benefited from better capacity to carry out ADLs and IADLs but were worse off with respect to mood and mortality (Calvo, 2006). A Japan-based longitudinal study of depressive symptoms in people aged 55–64 found that men had fewer depressive symptoms when they engaged in more hours of paid work or volunteering. They also had more depressive symptoms when they lost their job, but volunteering mitigated the effects of job loss. Women who engage in multiple productive roles, not housework alone, may experience less depression (Sugihara et al., 2008). A systematic review found an absence of negative impacts from working beyond retirement age, and 4 of 10 articles in the study showed statistically significant positive effects on mental health outcomes. The researchers hypothesized that the mechanisms for improvements include “productive societal roles, income, and social support” (Maimaris et al., 2010, p. 532). They emphasize that the benefits are not universal and should not be used to justify an increase in the retirement age (Maimaris et al., 2010).

A more recent review article evaluates 19 studies—12 on the impacts of an increase in retirement age and 7 on working beyond retirement age. The review found that increased retirement age increased labor force participation2 among older workers and shifted their preferred and expected retirement age higher. But the findings on health and well-being were not comparable, and the authors therefore conclude that the evidence for a beneficial impact of increased retirement age on older workers' health and well-being is “scarce and inconclusive” (Pilipiec et al., 2021, p. 298).

A wide-ranging systematic literature review highlights the nuances in the relationships between work and health:

- Characteristics of and changes to work-task patterns over time determine whether work makes people more or less healthy. For example, physically and/or mentally exhausting work makes people less healthy unless work tasks change over time.

- Variety in work tasks can decrease age-related cognitive decline.

- Characteristics of the job and time spent doing the same job can lead to loss of productivity and motivation.

The researchers found “tentative evidence that underscores the importance to implement moderate novelty in work tasks in order to keep the brain active and to counteract age-related decline in functioning” (Staudinger et al., 2016, p. S287).

Relationships Between Retirement and Healthy Longevity

Another way to look at the impacts of work on older workers is to consider the effects of retirement. Like the literature on the impacts of work on health, this literature shows that retirement's impacts are heterogeneous. Many studies suggest that retirement has negative effects on health, although studies do not always control for selection bias. People with poor health are more likely to retire than are people with good health, and a study that fails to control for this effect will suggest that retirees are less healthy than people who continue to work. A leading U.S.-based longitudinal analysis of Health and Retirement Study data suggests that retirement can lead to decline. Even after controlling for confounding variables, the evaluation showed that, in the 6 years after retirement, retirees experienced increases in mobility challenges and ADLs (5–16 percent), chronic condition (5–6 percent), and a decline in mental health (6–9 percent) (Dave et al., 2006). Another study found that negative effects of retirement on cognitive performance were more prominent among physical workers than among knowledge workers, with those of the lowest socioeconomic status showing the greatest loss in performance. Variation was seen among the different types of workers studied in the effects of continuing to work, working part-time, or retiring and then returning to work (Carr et al., 2020).

Other studies have added nuance to the picture. Findings of a 2017 longitudinal study of cognitive function suggest that work, not retirement, is protective against major cognitive decline when a person leaves the workforce at the normal retirement age, but that early retirement is even more protective against high levels of cognitive decline (Celidoni et al., 2017). Using longitudinal modeling, Westerlund and colleagues (2010, p. 1) showed that younger retirement “did not change the risk of major chronic diseases but was associated with a substantial reduction in mental and physical fatigue and depressive symptoms, particularly among people with chronic diseases.”

One research team evaluated the relationships between individual characteristics and life satisfaction among people working after retirement age, defined as the combination of pension income and participation in paid work, in the European Union (EU). Based on data from 16 countries, the “relationship between life satisfaction and working after retirement” age depends “on individual pension income and the resources available” to the person (Dingemans and Henkens, 2019, p. 662). Life satisfaction is greater among working retirees in lower-income EU countries than among their counterparts in higher-income EU countries. Life satisfaction is also greater for working retirees without partners (Dingemans and Henkens, 2019).

This literature emphasizes that there is no yes or no answer to whether work or retirement is better for healthy longevity. Rather, it suggests the need to study subgroups to determine which individual and work characteristics can lead to better health in work and retirement.

Finding 3-1: The impacts of work and retirement on older people are heterogeneous. Overall, working has health benefits for many older people while adversely affecting the health of others. The same is true for retirement. Evidence that increasing the retirement age improves health is scant and inconclusive.

KEY TARGET: WORK AND RETIREMENT

Increasing Labor Force Participation Among Older Workers

While stereotypes portray older workers as less healthy, productive, and tech-savvy than their younger counterparts, the evidence suggests that older workers in knowledge jobs are superior in judgment, reliability, and mentoring skills and are indeed capable of mastering the technology requirements of their jobs. Along with an increased sense of competence, older workers become motivated to use their vast repertoire of skills to help others. All of these factors serve to improve workplace climate and reduce turnover among workers of all ages, thus lowering costs for employers. (Stanford Center on Longevity, 2021, p. 4)

To avoid a potential crisis arising from population aging, governments need to harness healthy longevity to support their economies. The most direct way to harness healthy longevity in service to the economy and government capital is to increase labor force participation among healthy older people. Government capital, in turn, can be used to provide support to advance healthy longevity (Aksoy et al., 2019). The potential gains in GDP and capital are tremendous. Barrell and colleagues predicted in 2009 that adding 1 year of work in the United Kingdom would raise its GDP by more than 1.5 percent in approximately 4 years, in addition to increasing total and government capital (Barrell et al., 2009).

In higher-income countries, the goal is to enable healthy people, especially those under age 65, to work for longer if they choose to. Lower-income countries already have high labor force participation rates among people over age 65 because many people work outside of the formal economy surviving on subsistence-level incomes. Absent a social pension, these people must work until they are physically or cognitively incapable of doing so. As discussed in Chapter 4, the goal for people with low incomes in all countries is to provide pensions.

A common objection in response to proposals to increase labor force participation among older people is that doing so will decrease employment opportunities for younger people. The “lump of labor fallacy,” which assumes that economies are inelastic and the number of jobs is static, “is probably the most damaging myth in economics” and has been largely discredited (Börsch-Supan, 2013, p. 10). Studies of 12 countries in North America, Europe, and Asia, for example, demonstrate that labor force participation rates among older people are positively correlated with labor force participation rates among younger people (Böheim, 2019).

Differences in Labor Force Participation Rates

Labor force participation rates differ across countries and over time. Within Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, the exit age from the labor force is a U-shaped curve (see Figure 3-2). Policies that encouraged older workers to retire and the global financial crisis of 2008 drove declines in labor force participation among older people. The goal of these policies was to decrease youth unemployment by having fewer older workers, but as discussed above, this notion has been discredited, and youth unemployment remained high even after older workers retired at earlier ages.

FIGURE 3-2

Labor force participation at ages 55–64 (left axis) and average labor market exit age (right axis) for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. SOURCE: Boissonneault et al., 2020.

In the United States, the only age group that has seen increased labor force participation rates year after year since 1996 is people aged 55 and older (see Figure 3-3). That labor force participation at younger ages is shrinking emphasizes the need to maintain or increase participation among people aged 55 and older. The steep declines in overall participation rates that occur after age 55 may be a high-value target for incentives to encourage healthy participants to continue working up to and even after normal retirement age (the age when a person is eligible for full government pension benefits). Similar patterns have been observed in Europe. Consistent with this growth in older workers, the United States has seen a radical shift in workers' retirement expectations: the percentage of workers expecting to work past age 65 tripled between 1991 and 2018 (Munnell et al., 2019).

FIGURE 3-3

Civilian labor force participation rate by age, 1996, 2006, 2016, and 2026 (projected). SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019.

Labor force participation rates for those older than 64 differ dramatically from high- to low-income countries. Europe has the lowest participation rates for high-, upper-middle-, and lower-middle-income countries, with rates of 6.89, 6.0, and 13.6, respectively, while low-income countries in Asia and Africa have an average participation rate of 51.4, explained by the absence of pensions and people's need to work to survive (Staudinger et al., 2016).

Current labor force participation among people aged 65 and older debunks the flawed assumption that people in this age group are unproductive. In 2018, their participation rates ranged from 13.7 percent in high-income countries to 49 percent in low-income countries. In high-income countries, their participation rate increased by 38 percent between 2000 and 2018, while the rate in lower-income countries saw minimal change (UN Population Division, 2018) (see Figure 3-4). Even now, the percentage of people aged 50 and older who are healthy exceeds the percentage in the labor force, suggesting that, with the current levels of good health, many people who have exited the workforce have the health that would enable them to participate.

Longer Working Life

As with overall labor-force participation, structural, cyclical, and accidental factors play an important role in shaping labor-force participation of older adults. However, labor-force participation of older adults also has its own specificities. Two key conceptual perspectives that help to further unravel labor-force participation of older adults are whether they need, want, and are healthy enough to work (i.e., supply side) and whether employers retain, train, or hire them (i.e., demand side). (Staudinger et al., 2016, p. S284)

As the above quotation suggests, attempts to influence labor force participation need to address the supply side by encouraging older people to remain in or rejoin the labor force. Reasons for remaining in the workforce past normal retirement age (the full pension eligibility age) vary. A common reason across countries is the need for income, as is the case in low-income countries (Staudinger et al., 2016). In Europe, people who lack the resources to retire include those who have engaged in more lifetime part-time work or self-employment and divorced women who do not remarry; thus, “[i]nequalities that develop across the course of work careers seem to continue after retirement, which may also have serious policy implications” (Dingemans and Möhring, 2019). In a U.S.–based survey about working, roughly half of those aged 62 and older rated “the ability to provide for themselves financially” as important or essential (Maestas et al., 2018).

Table 3-1 summarizes individual, job, family, and socioeconomic influences found to be associated with workforce exit in OECD countries. Individual factors include enjoyment in work, satisfaction in using skills, a sense of accomplishment, the ability to be creative, work ethic, and generativity (Kooij et al., 2008); personal growth, striving to help other people, and contributing to society (Kooij et al., 2011); and remaining active (Staudinger et al., 2016).

Given the steep increase in workforce departures beginning at about age 50 in OECD countries, it is important to understand why people in this age group leave the workforce. One study of workers who retired earlier than planned found poor health to be the most common reason. Health-related disabilities impact the ability to work in 25 percent of workers aged 60–61, and poor health decreases an older worker's chances of working longer. Workers in poor health are more likely than their healthier counterparts to transition out of work and into unemployment, disability pensions, and early retirement (Dingemans and Möhring, 2019).

TABLE 3-1

Factors Associated with Workforce Exit, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Countries.

Less common factors influencing a person's decision to leave the formal workforce earlier than planned include caregiving responsibilities and job loss without replacement. Other factors include unavailability of the jobs or job characteristics that would lure people away from leisure (Staudinger et al., 2016) and poor physical or overly demanding work environments (Nilsson, 2016).

Age Discrimination and Ageism in Employment

Older people who want to work face employment discrimination and ageism, which affects their ability to continue to work and be hired. People in the United States who are laid off after age 50 are far less likely than younger workers to be reemployed. Two of three respondents to an AARP survey of people in the United States over age 45 who were employed or looking for work reported seeing or experiencing age discrimination in their workplace (Perron, 2018). The San Francisco Federal Reserve conducted a correspondence study in which it submitted more than 40,000 realistic job applications for 13,000 positions for young (29–31), middle-aged (49–51), and older (64–66) people. Older female applicants for low-skill administrative and sales positions received 47 percent and 36 percent fewer callbacks, respectively, compared with their younger counterparts. Older male applicants for sales positions received 30 percent fewer callbacks compared with their younger peers. Older versus younger male applicants for janitorial and security positions received fewer callbacks, but the difference was not statistically significant (Neumark et al., 2017). Likewise, a HelpAge International report documents extensive employment discrimination in African countries (Nhongo, 2006). Findings of a recent study evaluating age and gender requirements in job boards in China and Mexico were similar (Helleseter et al., 2020). The researchers examined the characteristics of job ads across multiple online job boards, looking specifically for age, gender, and skill requirements. They found that more than 77 percent of open job postings on an online job board popular for low-skilled positions specified a maximum age, which essentially eliminated all possibility of older workers obtaining those positions. When they combined age and gender requirements across all four job posting sites, they found a striking difference. Across three job boards in China and one in Mexico, the number of postings specifying gender was roughly equal, but more postings seeking women were limited to those under age 25 (ratio of 1.4:1). Postings seeking workers over age 35 leaned toward men, with ratios of 2.5:1, 4:1, and 5:1 applying for the job boards in China and 2.5:1 for the job board in Mexico. Although the data do not extend to older ages, the apparent discrimination against women as they age has troubling implications for obtaining these jobs.

Older Workers' Productivity and Value on Intergenerational Teams

A significant barrier to labor force participation is the perception that older people bring down the economy and the workplace. The authors of one study concluded that “population aging slows earnings growth across the age distribution” and “leads to declines in the average productivity of workers in all age groups” (Maestas et al., 2016, p. 3). Börsch-Supan and Weiss (2016) suggest that these studies reflect measurement, selectivity/endogeneity, and aggregation challenges. To overcome these challenges, they conducted a productivity study in a truck manufacturing plant with laboratory-like conditions and a large number of observations. They found no evidence to support the notion that older workers (up to age 65) are less productive than younger workers. They found that older workers were slightly more likely to make errors, but they rarely made severe errors, and the evidence suggested that experience kept their productivity from declining. Another recent study found that productivity declines are reduced or eliminated when older workers are healthy (Cylus and Al Tayara, 2021), suggesting that the magnitude of older workers' impact on productivity is not homogeneous or fixed and can be offset by improved health.

Examining the benefits of employing older workers, Mercer, a human capital measurement and management firm, found that the contributions of older workers change over time, with their individual contributions declining as the productivity of people around them increases. The study also found that older workers have longer tenures, and workers of all ages stay in a job longer when they have older managers (Stanford Center on Longevity, 2017).3 Two recent studies considering the relationship between positive business outcomes and intergenerational workplaces help explain Mercer's observations. The first found a relationship between being involved in knowledge transfer among older and younger workers and the retention of both groups of workers (Burmeister et al., 2020). The second found that “age diversity was positively associated with performance” as a result of “increased human and social capital,” with an even greater effect in settings where employees work in diverse environments and when the management is age-inclusive (Li et al., 2021, p. 71), and an OECD study linked a 10 percent higher share of workers aged 50 and older with firms being 1.1 percent more productive (OECD, 2021).

Older people are successful as entrepreneurs as well. Venture capitalists invest heavily in people in their 20s and 30s on the assumption that they have the best chance of creating a high-growth start-up. But a recent analysis suggests that the most successful founders of “growth-oriented” firms with large economic impacts are between their late 30s and early 50s, with those at age 65 having more success than those under age 25 (Azoulay et al., 2020).

Incentives for Older People to Work

The most common strategy governments have used to increase labor force participation among older workers is raising the retirement age. In member countries of the OECD and G20, for example, pension ages are rising under pension reform laws, with Denmark instituting the most extreme increase in normal retirement age, from age 65 in 2019 to a projected age 74 in 2070 (see Figure 3-5). Italy, the Netherlands, and Estonia have enacted a future retirement age of 70 or older, with few workers expected to have a future retirement age below 65 (OECD, 2020). Between 2017 and 2019 in OECD countries, most pension reforms loosened age requirements for eligibility, increased benefits (including safety net pensions aimed at preventing poverty among older people), expanded coverage, or encouraged private savings (OECD, 2020).

FIGURE 3-5

Normal retirement age for men entering the labor market at age 22 with a full career. NOTE: OECD = Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development. SOURCE: Republished with permission of OECD, from Pensions at a glance 2019: OECD and G20 indicators (more...)

Raising the pension eligibility age increases labor force participation among older people, but likely at a cost to vulnerable older adults. France increased its retirement age, for example, but experienced high rates of unemployment for people who were between the old and new retirement ages, likely because the government had increased labor supply while doing nothing to stimulate demand for that increased supply (Guillemard, 2016). Another analysis found that changing the normal retirement age from 65 to 67 netted only an additional 0.6 years of work, and that individuals with low education levels and blue collar jobs suffered under the changes because of the challenge of getting a job at older ages (Etgeton, 2018).

Given concerns about pension eligibility resulting in more income inequality, countries have initiated alternative approaches to increasing labor force participation rates and reaping the associated GDP boost through incentives. Between 2017 and 2019, OECD countries implemented the following policies to create incentives to continue to work, instead of punishing those who do not remain in the workforce:

- increasing earnings exemptions (Canada);

- paying a lump sum to people who work more than a specified number of hours after reaching retirement age (Denmark);

- abolishing the maximum limit of pension accrual years (Belgium); and

- instituting age-targeted tax credits for people over age 65 who continue working (Sweden) (Laun, 2017; OECD, 2020).

The Future of Work and Retirement for Older People

Some have called for an end to retirement as an either/or state. Even now, people want a “glide path” into retirement whereby they can reduce hours, have more time off, and possibly change roles instead of abruptly leaving the workforce. Emerging patterns among current older workers provide insight into what will keep future people in the workforce. For example, older Americans have specific preferences about working past retirement, such as setting their work schedule, limiting their physical activity, having paid time off, and working alone. Figure 3-6 compares the preferences of four age groups in the United States—25–34, 35–49, 50–61, and 62+—with respect to their willingness to pay for job amenities in proportion to their wages. In all but two instances, the value assigned to job amenities was higher among older compared with younger people. The exceptions were “training opportunities” and “frequent opportunities to serve,” also described as opportunities for meaningful work. Lower rates of training and fewer opportunities to serve that are observed may reflect older workers' preferences (Maestas and Jetsupphasuk, 2019; Maestas et al., 2018).

FIGURE 3-6

Estimates of willingness to pay for job amenities by age group, expressed in proportion to respondent wage. SOURCE: Maestas et al., 2018.

While these findings likely apply in other high-income countries, they may be less relevant in low- and middle-income countries, where more older workers are driven by need, not preferences. However, older workers in low- and middle-income countries may benefit from changes in job characteristics that are more favorable for older workers. For example, automation is replacing more physically demanding jobs in Thailand, and this shift is allowing older workers to remain in the workforce for as long as they choose (Moroz et al., 2021). Employers also can create more supportive environments for older workers relative to current workplaces by, for example, allowing flexible work schedules; providing part-time work; and funding job retraining for people whose jobs involve manual labor that they are no longer able to perform, allowing them to transition to more appropriate roles.

In some instances, especially in the United States, hiring older workers can be more costly than hiring younger workers. In the United States, for example, employers pay more for health insurance for older workers than for younger workers. When considering options for increasing labor force participation, governments may wish to focus on laws and regulations that create disincentives for hiring older workers.

Workers in the Informal Economy

The percentage of the workforce participating in the formal economy varies among global regions. In contrast with work in the informal economy, employment in the formal economy is characterized by employment agreements, scheduled hours, consistent and scheduled pay, and participation in private and government pensions. Much of the caregiving and domestic workforce, overwhelmingly female, works in the informal economy. In addition, the world in general has seen the rise of new forms of work other than full-time work with benefits, including work arrangements and short-term contracts without guaranteed hours, sometimes described as the gig economy. Among OECD countries, informal and new forms of work account for a third of employment (OECD, 2020). In comparison, 70 percent of employment in emerging markets and developing economies is in the informal sector, with self-employment accounting for different proportions of the informal workforce in different regions (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021).

Employment in the formal economy comes with legal protections and minimum standards for financial stability. The informal economy and new forms of work are typically flexible but come without protections such as from dangerous working conditions, unpredictable income, low earnings, and limited access to health care and pensions (OECD, 2020). In the United States, where employers provide a majority of health insurance coverage, workers outside of the formal economy often lack access to affordable health insurance. Worldwide, workers in the informal economy and new forms of work are vulnerable to income disruption and job loss and may lack access to a financial safety net and pensions (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021).

From the government perspective, both informal and new forms of work present challenges. According to a World Bank report, “a large informal sector weakens policy effectiveness and the government's ability to generate fiscal revenues” (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021, p. 16). Governments that lack resources have a limited ability to shrink the informal sector by providing social protection programs and public services (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021; Schneider et al., 2010). This, in turn, limits governmental engagement by private-sector companies and workers and increases the size of the informal sector (Loayza, 2018; Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021; Perry et al., 2007).

The COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating to vulnerable populations around the world, and informal-sector workers are no exception. According to the World Bank, during the pandemic, workers in the informal sector were more likely than those in the formal sector to lose jobs, suffer income losses, live in areas with poor access to public health interventions and sanitation, and lack access to social safety nets (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021).

Governments can implement policies to promote the transfer of the informal sector's resources to the formal sector and to provide better public services and social safety nets for workers in the informal sector, especially during and in the aftermath of the pandemic (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021). Doing so can reduce inequities between workers in the formal and informal sectors. Establishing legal rights for the working poor, including improved access to the justice system and property, business, and labor rights, has the potential to help workers in the informal sector by providing improved working conditions and the right to seek payment if it is wrongfully withheld (Dasgupta, 2016). Finally, governments and corporations can set targets for hiring people into the formal economy by providing on-the-job training, given that many workers in the informal economy lack education and training (Dasgupta, 2016). Implementing policies to protect workers in the informal sector in the near term is important in light of forecasts of a postpandemic decrease in physical capital, “erosion of the human capital of the unemployed,” and weakened global trade (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021, p. 5).

Finding 3-2: If older people were to stay in the labor force longer in high-income countries, it would increase the gross domestic product, government capital, and personal capital.

Finding 3-3: Evidence suggests that older adults who work do not take away jobs from younger workers.

Finding 3-4: Workers in the informal economy are at significant risk of financial instability.

Conclusion 3-1: Raising the pension eligibility age increases the length of time people stay in the workforce, but without safety nets for people who cannot find jobs or are unable to work, the policy penalizes people with limited resources.

Conclusion 3-2: Raising the pension eligibility age increases workforce participation by older workers, but doing so to improve health is not justified by the evidence, and it may increase inequality.

Conclusion 3-3: Maintaining economic equilibrium as the population ages will require increased workforce participation by older people.

Conclusion 3-4: Incentives to recruit and retain older workers will be an integral part of increasing workforce participation by older people.

Conclusion 3-5: Governments can increase voluntary workforce participation among older workers by creating incentives to work and removing barriers to work.

Recommendation 3-1: Governments, in collaboration with the business sector, should design work environments and develop new policies that enable and encourage older adults to remain in the workforce longer by

- a.

providing legal protections and workplace policies to ensure worker health and safety and income protection (including during periods of disability) across the life course;

- b.

developing innovative solutions for extending legal and income protection to workers participating in alternative models of work (e.g., gig economy, informal sector);

- c.

increasing opportunities for part-time work and flexible schedules; and

- d.

promoting intergenerational national and community service and encore careers.

KEY TARGET: VOLUNTEERING

Older adults have more prosocial tendencies than younger people (see Chapter 4). Generativity, the act of contributing to nonfamily members of younger generations, is a manifestation of these prosocial behaviors. Generative acts among older adults include contributions through family roles, friendship, community activity, volunteering, and work. Prosocial behaviors that overlap with generative acts include volunteering formally or informally (Wenner and Randall, 2016). The emphasis of this section is on the role of formal volunteer structures for a future of healthy longevity. Although it is not the emphasis of this section, the commission also recognizes the importance of informal contributions older people make to family, friends, and community.

Benefits to Older Volunteers

Formal volunteering in later life supports healthy longevity, enhances an older person's sense of meaning and purpose, and provides financial and social value to society (Carr et al., 2018). Studies have shown positive effects of volunteering on mortality risk (Harris and Thoresen, 2005), cognitive function (Guiney and Machado, 2018), depression (Li and Ferraro, 2005), physical function, positive affect, and happiness (Anderson et al., 2014). “Practices of contributing, giving, and passing on have an important role in the self-identification of older people as contributing citizens, as individuals with self-worth, significance, and meaning” means that volunteering meets “basic psychological needs of self-esteem, socialization, life satisfaction, and contribution to others” (Stephens et al., 2015, p. 24).

Impacts of volunteering vary among subpopulations, and some findings in this regard are perplexing. One study found that volunteering reduced mortality risk in healthy older people but not those in fair health or with functional limitations. Another study found an association between volunteering more than 800 hours a year and worse negative affect among people without a partner and with a moderate level of education. In many cases, those people who are highly vulnerable benefit the most, with the strongest associations being found between

- higher level of happiness and those of lower socioeconomic status;

- positive affect and resilience and having more chronic conditions;

- reduced depression and older people with dual sensory loss;

- reduced mortality and nondrivers, especially in rural areas; and

- reduced mortality and older adults with low social interaction (Anderson et al., 2014).

Who Volunteers?

Compared with older people who do not volunteer, older volunteers are, on average, healthier, wealthier, younger, and more educated (Anderson et al., 2014). Volunteering is more prevalent among people who attend religious services relative to those who do not, with differences among religions and denominations. Many groups of older people face barriers to volunteering, and often those who face the most barriers would benefit most from volunteering. There is also tremendous variation in rates of volunteerism among countries, with a 10-fold variation in rates across Europe. The wealthiest countries have the highest rates of volunteering (Southby et al., 2019).

For older people, barriers to volunteering include “poor health and physical functioning, poverty, stigma, lack of skills, poor transport, time constraints, inadequate volunteer management, and other caring responsibilities” (Southby et al., 2019, p. 911). Volunteering also consumes resources, so people with fewer resources may lack the opportunity to benefit from volunteer opportunities or be limited to specific volunteer roles or organizations. Older people, among other subgroups, report that they do not feel welcome in some volunteer programs (Southby et al., 2019).

The combination of barriers driving lost opportunities for improved health creates concerns about volunteerism and equity that need to be addressed if communities or countries choose to promote volunteerism. One publication makes the case that online volunteering shows promise for enabling volunteerism among people with mobility challenges and others who cannot participate in person, and may reduce ethnic and racial discrimination encountered by members of some groups (Seddighi and Salmani, 2018).

Societal Benefits

Programs using older volunteers can have significant societal value beyond their impacts on the volunteers. Experience Corps is the first evidence-based model for senior volunteering designed for both societal impact and health promotion and improved well-being for the older volunteers. The program involves placing a minimal number of older volunteers in schools and training them in teams to enable a team dynamic to thrive. This evidence-based senior volunteer program was designed to create multiple positive outcomes for

- children's academic success in public elementary schools;

- older volunteers' health, function and well-being, and ability to meet generative goals;

- teachers' and schools' success in educating and in improving the social climate; and

- communities' social cohesion.

The program's creators wanted to show that volunteer programs could provide meaningful and high-impact roles for older people by using their assets effectively and meaningfully and bring generative fulfillment by supporting the academic success of the next generation (Fried et al., 2004).

Experience Corps was designed using public health science to amplify the physical, cognitive, and social activity and engagement of older adults within and beyond their existing roles. Intentionally placing older volunteers in a school and training them in teams created efficiencies within the schools and new vehicles for establishing social networks (Fried et al., 2004). Students' behavior, school climate (Rebok et al., 2004), and teacher efficacy and satisfaction improved in Experience Corps schools (Martinez et al., 2010). One critical design element enabling participation by lower-income volunteers was a stipend that offset some costs of volunteering (Tan et al., 2010). Box 3-1 includes a description of a successful volunteer program in South Africa.

BOX 3-1

South African Peer Support Intervention.

The Value of Volunteering

A 2020 economic analysis of work, volunteering, caring for grandchildren, and support for non–household members in Europe and the United States quantified market and nonmarket contributions of people over age 50. The analysis showed that older adults contribute 29 percent (Europe) and 40 percent (United States) of GDP per capita through market and nonmarket activities (see Figure 3-7). For those over age 60 in Europe and the United States, the value of nonmarket contributions was estimated to be 50 percent and 84 percent, respectively, of the value of market contributions. It is important to note that the value of contributions measured in the study is less than the actual value contributed by older people because it does not include the value of household activities or care for disabled adults within the household, such as disabled adult children or spouses (Bloom et al., 2020).

FIGURE 3-7

Value of contributions by age group in the United States (top) and Europe (bottom). NOTE: Non-HH = non-household. SOURCE: Bloom et al., 2020.

Levers for Action

Volunteerism, along with other informal volunteer activities of older adults, can generate social capital, benefiting both the volunteer and the recipient of the volunteer services. The commission agreed that the evidence justifies government investments in shoring up and expanding existing volunteer programs. Some commissioners, but not all, went a step further in calling for major investments in national programs for older volunteers.

Before scaling up volunteer programs, it will be necessary to overcome the many barriers that prevent older adults from volunteering. It is also important to ensure that the failure to volunteer does not stigmatize people who do not volunteer.

Finding 3-5: Evidence suggests that participating in formal volunteer programs improves health outcomes for older people. People on the receiving end of volunteer efforts also benefit.

Conclusion 3-6: To maximize the value of volunteer contributions to both older people and society, existing government and private-sector structures need to encourage the involvement of older volunteers; formal programs need to provide meaning and purpose for volunteers, along with financial support to offset costs they may incur; and governments at all levels need to create or shore up existing volunteer programs for older people.

Research Questions

Research in the following areas is needed across all countries and all ages to better understand and promote volunteering. Data to support this research would be best gathered by collaborations between researchers and volunteer organizations:

- how to measure the impact of global volunteer inputs, and

- time-use and other surveys of volunteers.

KEY TARGET: LIFELONG EDUCATION AND RETRAINING

This report envisions a future in which the 20th-century model of remaining in one career for most of one's adult life is rare. Instead, the commission envisions multiple careers across a person's working life. To make this vision a reality, education and retraining will be critical.

Education during early childhood and young adulthood influences health and functioning across the life course. The relationships are strong, even if the mechanisms are still being disentangled. Evidence suggests two main influences of education on health. First, education itself—independent of work and labor force participation—has a beneficial impact on late-life healthy longevity. Second, education puts people on a social and career trajectory leading to occupational gains and more labor force participation. Postsecondary education also influences health into older ages (Böheim et al., 2021). Notably, historic declines in the incidence of dementia have been linked to increased educational attainment (Valenzuela and Sachdev, 2006).

Literacy and Numeracy

Literacy and numeracy are foundational to work, financial literacy, health literacy, and even community and social engagement. Literacy is defined as “understanding, evaluating, using and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one's goals and to develop one's knowledge and potential” (OECD, 2012, p. 20). Numeracy is “the ability to access, use, interpret, and communicate mathematical information and ideas, to engage in and manage mathematical demands of a range of situations in adult life” (OECD, 2012, p. 34). The good news is that global literacy rates have climbed steadily for the past 50 years, especially among women (Roser and Ortiz-Ospina, 2018). The bad news is that today, women over age 65 have the lowest literacy rate, 73 percent, compared with people aged 15–24, whose literacy rate is 91 percent (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2017). Among 23 countries included in the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, 19 percent of people have a very low numeracy level4 (14 percent) or lack numeracy (5 percent) (Rampey et al., 2016).

The global challenge of low literacy impacts older people's ability to participate in the workforce, volunteer programs, and even family caregiving. An expert in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, described the phenomenon of some older people raising grandchildren who had a limited ability to help their grandchildren with their homework because they had lower literacy than younger people.5 Older adult literacy is heavily oriented to health. A United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report states that a focus on promoting youth literacy, versus adult literacy, is appropriate because most improvement in literacy occurs at a young age, and studies suggest that adult literacy programs do not show large effects on national literacy rates (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2017). In contrast, the commission emphasizes the need to develop literacy and numeracy across the life course to enable participation in society, the labor force, and health care. Attention to literacy across the life course will help ensure that older people of the future have higher rates of literacy and numeracy than is currently the case.

Completion of Secondary Education

The commission identified completion of secondary education as a target that sets the stage for a life of literacy and workforce entry across countries of all incomes, based on the evidence that more and high-quality education is associated with increased productivity and earnings. In low- and middle-income countries where informal economies dominate, completing secondary education improves a person's chances of working in the formal economy (Sheehan et al., 2017).

Postsecondary and Lifelong Training and Education

Two recent publications emphasize the importance of adult education and retraining to the longer work lives that will come with healthy longevity (Gratton and Scott, 2016; Stanford Center on Longevity, 2021). Given the recent rate of technological change, it is difficult to predict how education and training will be delivered 30 years from now. The centrality of physical classrooms is already declining, with more students studying online. Yet, while postsecondary online education is growing, it has consistently been found to be less effective than in-person learning. In one recent study, for example, bachelor's degree students in online programs in Columbia had worse academic results compared with those who participated in person, although the results were less conclusive for shorter technical certificate programs (Cellini and Grueso, 2021). These findings suggest an opportunity to develop more effective approaches to distance education, such as virtual reality or augmented reality (Babich, 2019) or some other technology not yet developed.

Currently among age groups in OECD countries, the percentage of people enrolled in all forms of education drops steeply from ages 20–24 (41 percent), to 25–29 (16 percent), to 30–34 (8 percent), to 35–39 (5 percent), to 40–64 (2 percent) (OECD, 2022). The percentage of people over age 65 enrolled in any form of education is so small it is not reported. In a future with multiple career transitions, the commission anticipates higher educational enrollment across the adult life course.

The overwhelming majority of job training and retraining takes place in the workplace. A 2013 UNESCO report describes the value of learning through practice, including for older workers, who can use such learning to remain employable across their working life (Billett, 2013). In 2019, it was estimated that by 2021, 1.7 million more adults in the United States would need a postsecondary degree or certificate to meet market demands. Educational programs that accommodate the needs of and provide support for older students could help fill this gap (Cummins et al., 2019).

Technical Colleges, Community Colleges, and Global Counterparts

Community colleges and their global counterparts (e.g., colleges of continued education, polytechnic or technical colleges, and technical and continued education) are a common form of tertiary education globally. The U.S. community college concept has been adopted across countries such as Brazil, Vietnam, and Qatar (Spangler and Tyler, 2011). Benefits of community colleges include a postsecondary curriculum; lower costs than universities; and accessibility for different types of adult learners, including workplace learners and displaced workers (Raby et al., 2017). Community colleges are also more responsive than other forms of tertiary education to local community needs and more able to shift curriculum (Chase-Mayoral, 2017), but they are not limited to acting locally. More broadly, community colleges in low- and middle-income countries serve as a link between local communities and the global market as students receive developmental, general education that prepares them to transition to skilled employment or a higher university education.

Conclusion 3-7: Education at all levels will be critical to healthy longevity. To be effective, educational, upskilling, and retraining programs will need to include delivery through multiple modalities and pedagogical approaches that work for people of all ages, as well as expanded on-the-job and vocational training.

Metrics and Research Questions

Given that structures to provide education and retraining across the life course are emerging, there are few metrics for such programs that would be of value, beyond a count of enrollment of people over age 25 in these programs, stratified by age in 10-year age bands and gender. To expand the availability of education and retraining options, research on the following questions is needed:

- What characteristics of education and retraining programs would be needed to recruit people over age 25 into postsecondary education?

- Do those characteristics change within age bands across adulthood?

OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE ECONOMY TO SUPPORT HEALTHY LONGEVITY

Businesses can contribute to healthy longevity by retaining and hiring older workers, as described above. They can also contribute by creating products that support health, function, health care delivery, and much more. Coughlin, an expert in products for older adults, describes how “gerotechnology” focuses on health and other basic needs of older people because of the notion that “older adults are problems to be solved.” He counters that view with a simile: “Imagine if I gave business students a blank slate to imagine products for a different age group—teenagers, say—and the only products they could come up with were acne creams and crutches for when teens injure themselves performing ill-considered stunts.” He characterizes the current approach, which aligns with how businesses and MBA students think about older people, as a “colossal failure of imagination” (Coughlin, 2017, p. 67).

Engineers working on products to support older people start first with the concept of radical empathy: it is necessary to understand what people want before one can begin to design products for them. As Coughlin emphasizes, older people do not want products that make them feel old. Thus, some of the most successful technologies for older people were not designed as technologies for older people. For example, Uber and Lyft have been adopted as transportation for some subsets of older adults (Mitra et al., 2019). Similarly, many caregivers and older adults are using voice-controlled intelligent personal assistants (e.g., Amazon Echo, Google Home). In a study of product reviews, researchers learned that older adults and caregivers use these devices for entertainment (e.g., “For two very senior citizens … we have really had fun with Echo. She tells us jokes, answers questions, plays music.”), companionship, home control, reminders, and emergency communication (O'Brien et al., 2020). A third example is the growing use of medical alert devices.

Within health care, there are many ways technology can support older people, particularly in remaining independent. Devices already exist that can passively monitor heart rate and breathing, detect a fall and alert a family member or emergency services, monitor sleep for changes associated with such conditions as pneumonia, or identify neurodegenerative disorders based on gait patterns captured by a floor mat. Additional health-related technologies and pharmaceuticals are described in Chapter 6. There are a number of additional areas of potential for innovation in technology to support older people:

- Communications and human–machine interfaces will be transformed with clear applications for older people who have impairment of one or more sensory systems, but eventually with such broad applications as language processing and remote robotics.

- Consumer industries need to transform for a world with healthy longevity, including food, fashion, appliances, and home furniture, by creating new innovations and businesses, challenging traditional players, and creating new scale players.

- The distinction between products that one wears and those one consumes will blur, bringing together technologies and scale players to interface into horizontals that do not exist, and eventually connecting with health and physiology/performance, blurring the distinction between consumer products and medical products. The development of direct-to-consumer digital health products is beneficial for people with health care needs who lack access to care because of financial, geographic, and other barriers (Cohen et al., 2020). It is important that products be properly regulated and labeled with descriptions that outline digital health facts, specifications for what the products measure, and how those measures can be used.

Countries that can tap the potential in these areas will use consumer insights to understand this new consumer cohort, devise financing and funding models, understand how to protect and use massive datasets to improve lives and be competitive leaders, be innovative in their regulatory environment, and ultimately learn to meet the needs of older consumers in a rapidly iterative way. Some emerging countries will progress ahead of high-income countries, just as Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries did three decades ago in consumer electronics and the automotive industry. Access to capital or a large installed capital base may no longer be an overwhelming competitive advantage. Governments that embrace the challenge of healthy longevity as an opportunity will likely reap the greatest longevity dividends.

Recommendation 3-2: Governments, employers, and educational institutions should prioritize investments in redesigning education systems to support lifelong learning and training. Governments should also invest in the science of learning and training for middle-aged and older adults. Specifically, employers, unions, and governments should support training pilots that allow middle-aged and older adults to retool for multiple careers and/or participate as volunteers across their life span through the development of such incentives as

- a.

grants or tax breaks for employers to promote retaining and upskilling of employees (e.g., apprenticeship programs, retraining of workers in physically demanding jobs to enable them to engage in new careers in less demanding jobs);

- b.

special grants to community colleges and universities for the development of innovative models that target middle-aged and older students to support lifelong learning; and

- c.

grants to individuals for engaging in midcareer training.

METRICS AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Suggested metrics for evaluating progress on reaping the longevity dividend include

- older worker labor force participation rates,

- volunteer opportunities available for older adults, and

- proportion of the population involved in volunteer activities.

Research questions include

- development of metrics for identifying any inequality resulting from changes to government policies;

- identification of effective programs for supporting working careers from age 50 onward, ensuring that longer working lives support, rather than detract from, good health;

- the impacts of effective healthy longevity on labor force size and educational choices, and the fiscal implications of these impacts;

- mechanisms for how longer lives boost GDP;

- specific mechanisms responsible for the connections among work, retirement, and cognition;

- the degree of older adults' engagement in volunteering and the impacts of their volunteering, including monetary and nonmonetary value; and

- how to design volunteer roles for older adults that bring valued engagement and societal benefit and improve health and well-being.

CONCLUSION

Older people have intrinsic societal value regardless of their abilities to or choices in work, whether paid or unpaid. People continue to have meaningful roles in society as they age, so defining their engagement and contributions according to their personal values and preferences alongside societal expectations is a game changer.

REFERENCES

- Aksoy Y, Basso HS, Smith RP, Grasl T. Demographic structure and macroeconomic trends. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 2019;11(1):193–222.

- Anderson ND, Damianakis T, Kröger E, Wagner LM, Dawson DR, Binns MA, Bernstein S, Caspi E, Cook SL. The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: A critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(6):1505–1533. [PubMed: 25150681]

- Azoulay P, Jones BF, Kim JD, Miranda J. Age and high-growth entrepreneurship. American Economic Review: Insights. 2020;2(1):65–82.

- Babich N. Xd Ideas. 2019. [April 26, 2022]. How VR in education will change how we learn and teach. https://xd

.adobe.com /ideas/principles/emerging-technology /virtual-reality-will-change-learn-teach . - Barrell R, Hurst I, Kirby S. How to pay for the crisis or macroeconomic implications of pension reform. National Institute of Economic and Social Research. 2009;(333):2011–2012.

- Billett S. Learning through practice: Beyond informal and towards a framework for learning through practice. Revisiting Global Trends in TVET: Reflections on Theory and Practice. 2013;123

- Bloom DE, Khoury A, Algur E, Sevilla J. Valuing productive non-market activities of older adults in Europe and the US. De Economist. 2020;168(2):153–181.

- BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). Labor force participation rate for workers age 75 and older projected to be over 10 percent by 2026. 2019. [April 26, 2022]. https://www

.bls.gov/opub /ted/2019/labor-force-participation-rate-for-workers-age-75-and-older-projected-to-be-over-10-percent-by-2026.htm . - Böheim RN. IZA World of Labor. 2019. [April 26, 2022]. The effect of early retirement schemes on youth employment. https://wol

.iza.org/articles /effect-of-early-retirement-schemes-on-youth-employment/long . - Böheim R, Horvath T, Leoni T, Spielauer M. The impact of health and education on labor force participation in aging societies—Projections for the United States and Germany from a dynamic microsimulation. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2021.

- Boissonneault M, Mulders JO, Turek K, Carriere Y. A systematic review of causes of recent increases in ages of labor market exit in OECD countries. PloS One. 2020;15(4):e0231897. [PMC free article: PMC7190130] [PubMed: 32348335]

- Bongaarts J. Population aging and the rising cost of public pensions. Population and Development Review. 2004;30(1):1–23.

- Börsch-Supan A. Myths, scientific evidence and economic policy in an aging world. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 2013;1:3–15.

- Börsch-Supan A, Weiss M. Productivity and age: Evidence from work teams at the assembly line. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing. 2016;7:30–42.

- Burmeister A, Wang M, Hirschi A. Understanding the motivational benefits of knowledge transfer for older and younger workers in age-diverse coworker dyads: An actor–partner interdependence model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2020;105(7):748. [PubMed: 31697117]

- Calvo E. Does working longer make people healthier and happier? Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College; 2006. (Issue Brief WOB 2).

- Carr DC, Kail BL, Rowe JW. The relation of volunteering and subsequent changes in physical disability in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2018;73(3):511–521. [PubMed: 28958062]

- Carr DC, Willis R, Kail BL, Carstensen LL. Alternative retirement paths and cognitive performance: Exploring the role of preretirement job complexity. The Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):460–471. [PMC free article: PMC7117620] [PubMed: 31289823]

- Celidoni M, Dal Bianco C, Weber G. Retirement and cognitive decline. A longitudinal analysis using share data. Journal of Health Economics. 2017;56:113–125. [PubMed: 29040897]

- Cellini SR, Grueso H. Student learning in online college programs. AERA Open. 2021;7:23328584211008105.

- Chase-Mayoral AM. The global rise of the US community college model. New Directions for Community Colleges. 2017;2017(177):7–15.

- Cohen AB, Mathews SC, Dorsey ER, Bates DW, Safavi K. Direct-to-consumer digital health. The Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2(4):e163–e165. [PubMed: 33328077]

- Coughlin J. The longevity economy: Unlocking the world's fastest-growing, most misunderstood market. New York: PublicAffairs; 2017.

- Cummins PA, Brown JS, Bahr PR, Mehri N. Heterogeneity of older learners in higher education. Adult Learning. 2019;30(1):23–33.

- Cylus J, Al Tayara L. Health, an ageing labour force, and the economy: Does health moderate the relationship between population age-structure and economic growth? Social Science & Medicine. 2021;287:114353. [PMC free article: PMC8505790] [PubMed: 34536748]

- Dasgupta M. World Bank Blogs. 2016. [April 26, 2022]. Moving from informal to formal sector and what it means for policymakers. https://blogs

.worldbank .org/jobs/moving-informal-formal-sector-and-what-it-means-policymakers . - Dave DM, Kelly IR, Spasojevic J. The effects of retirement on physical and mental health outcomes. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006.

- Dingemans E, Henkens K. Working after retirement and life satisfaction: Cross-national comparative research in Europe. Research on Aging. 2019;41(7):648–669. [PubMed: 30782077]

- Dingemans E, Möhring K. A life course perspective on working after retirement: What role does the work history play? Advances in Life Course Research. 2019;39:23–33.

- Etgeton S. The effect of pension reforms on old-age income inequality. Labour Economics. 2018;53:146–161.

- Fried LP, Carlson MC, Freedman M, Frick KD, Glass TA, Hill J, McGill S, Rebok GW, Seeman T, Tielsch J. A social model for health promotion for an aging population: Initial evidence on the experience corps model. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;81(1):64–78. [PMC free article: PMC3456134] [PubMed: 15047786]

- Geffen LN, Kelly G, Morris JN, Howard EP. Peer-to-peer support model to improve quality of life among highly vulnerable, low-income older adults in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatrics. 2019;19(1):1–12. [PMC free article: PMC6805367] [PubMed: 31640576]

- Ghebreyesus TA. It takes knowledge to transform the world to be a better place to grow older. Nature Aging. 2021;1(10):865. [PMC free article: PMC8425467] [PubMed: 34518819]

- Gietel-Basten S, Saucedo SEG, Scherbov S. Prospective measures of aging for Central and South America. PloS One. 2020;15(7):e0236280. [PMC free article: PMC7380630] [PubMed: 32706837]

- Gratton L, Scott AJ. The 100-year life: Living and working in an age of longevity. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2016.

- Guillemard AM. France: Working longer takes time, in spite of reforms to raise the retirement age. Australian Journal of Social Issues. 2016;51(2):127–146.

- Guiney H, Machado L. Volunteering in the community: Potential benefits for cognitive aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2018;73(3):399–408. [PubMed: 29161431]

- Harris AH, Thoresen CE. Volunteering is associated with delayed mortality in older people: Analysis of the longitudinal study of aging. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(6):739–752. [PubMed: 16176953]

- Heller P. Is Asia prepared for an aging population? International Monetary Fund. 2006;6(272)

- Helleseter MD, Kuhn P, Shen K. The age twist in employers' gender requests: Evidence from four job boards. Journal of Human Resources. 2020;55(2):428–469.

- Kooij D, de Lange A, Jansen P, Dikkers J. Older workers' motivation to continue to work: Five meanings of age: A conceptual review. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2008;23(4):364–394.

- Kooij DT, De Lange AH, Jansen PG, Kanfer R, Dikkers JS. Age and work-related motives: Results of a meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2011;32(2):197–225.

- Laun L. The effect of age-targeted tax credits on labor force participation of older workers. Journal of Public Economics. 2017;152:102–118.

- Li Y, Ferraro KF. Volunteering and depression in later life: Social benefit or selection processes? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(1):68–84. [PubMed: 15869121]

- Li Y, Gong Y, Burmeister A, Wang M, Alterman V, Alonso A, Robinson S. Leveraging age diversity for organizational performance: An intellectual capital perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106(1):71–91. [PubMed: 32202816]

- Loayza N. Informality: Why is it so widespread and how can it be reduced? World Bank Research and Policy Briefs. 2018;(133110)

- Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature. 2008;451(7179):716–719. [PubMed: 18204438]

- Maestas N, Jetsupphasuk M. What do older workers want? In: Bloom DE, editor. Live Long and Prosper. London, UK: CEPR Press; 2019. p. 37.

- Maestas N, Mullen KJ, Powell D. The effect of population aging on economic growth, the labor force and productivity. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016.

- Maestas N, Mullen KJ, Powell D, Von Wachter T, Wenger JB. The value of working conditions in the United States and implications for the structure of wages. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018.

- Maimaris W, Hogan H, Lock K. The impact of working beyond traditional retirement ages on mental health: Implications for public health and welfare policy. Public Health Reviews. 2010;32(2):532–548.

- Martinez IL, Frick KD, Kim KS, Fried LP. Older adults and retired teachers address teacher retention in urban schools. Educational Gerontology. 2010;36(4):263–280.

- Mitra SK, Bae Y, Ritchie SG. Use of ride-hailing services among older adults in the United States. Transportation Research Record. 2019;2673(3):700–710.

- Moroz H, Naddeo J, Ariyapruchya K. Aging and the labor market in Thailand. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2021.