Clonidine for the Treatment of Psychiatric Conditions and Symptoms: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, and Guidelines

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Authors

Stephanie Chiu and Kaitryn Campbell.Context and Policy Issues

Clonidine is an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist which acts in the brain to decrease sympathetic outflow to the heart and peripheral vasculature.1,2 This has the effect of lowering cardiac output and vascular resistance and clonidine is used to systemically lower blood pressure.2 Clonidine is a fast-acting antihypertensive medication and its oral formulation typically requires twice daily dosing.3 In Canada, oral clonidine is indicated for the treatment of hypertension in patients for whom diuretics and beta blockers are ineffective, are contraindicated, or cause adverse effects.3 It is also indicated for the relief of menopausal flushing.4

Aside from antihypertensive effects, clonidine can exert sedative, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects.5 Therefore, beyond its approved indications, clonidine has been used more recently to treat a variety of psychiatric conditions which include attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Tourette syndrome.2,6,7 There have been case reports of patients abusing clonidine alone8 or in combination with opioids or benzodiazepines.8-10 Abuse of clonidine may be related to its above-mentioned effects10 as well as its reported ability to potentiate and extend opioid-induced euphoria.8

Previous CADTH reports pertaining to the management of ADHD11 and PTSD12 have identified evidence-based guidelines that suggest clonidine can be used for the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares and ADHD in adults. A 2013 CADTH report13 summarizing evidence for the use of clonidine and three other drugs for the treatment of adults with ADHD found no systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials of clonidine in this population. Evidence regarding the use of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions not restricted to PTSD or ADHD has yet to be summarized in a CADTH report. This report aims to review the clinical effectiveness of and evidence-based guidelines for clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms. It also reviews the harms associated with the potential misuse or abuse of clonidine.

Research Questions

- What is the clinical effectiveness of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms?

- What are the harms associated with the potential misuse or abuse of clonidine?

- What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of clonidine for the treatment of psychiatric conditions or symptoms in adults?

Key Findings

Evidence from a retrospective chart review suggested that clonidine may be effective in treating combat nightmares in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. A retrospective cohort study suggested that addition of clonidine to naltrexone therapy may reduce cigarette smoking and craving in an in-patient opioid detoxification setting. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a single dose of clonidine may adversely affect memory consolidation in patients with major depressive disorder and healthy volunteers. In a retrospective chart review, harms associated with clonidine overdose included impaired consciousness, miosis, hypothermia, bradycardia, hypotension, and severe hypertension and clonidine dose was negatively associated with minimum heart rate. No relevant evidence-based guidelines were identified. The small number of relevant studies identified (n = 4), the lack of large-scale studies (sample sizes of less than 120), and limitations in study design and quality prevented definitive conclusions from being drawn regarding the clinical effectiveness and safety of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including Medline, PsycINFO, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews (SRs), meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized studies, guidelines, and safety data. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2013 and January 17, 2018.

Rapid Response reports are organized so that the evidence for each research question is presented separately.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Selection Criteria.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in Table 1, they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2013. Results for clonidine used to treat opioid withdrawal were not reported as a separate CADTH report is planned for this topic. Articles on mixed populations (adult and pediatric) were excluded if they did not report results for the adult population separately.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included SRs were critically appraised using the AMSTAR II tool14 and randomized and non-randomized studies were critically appraised using the Downs and Black checklist.15 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

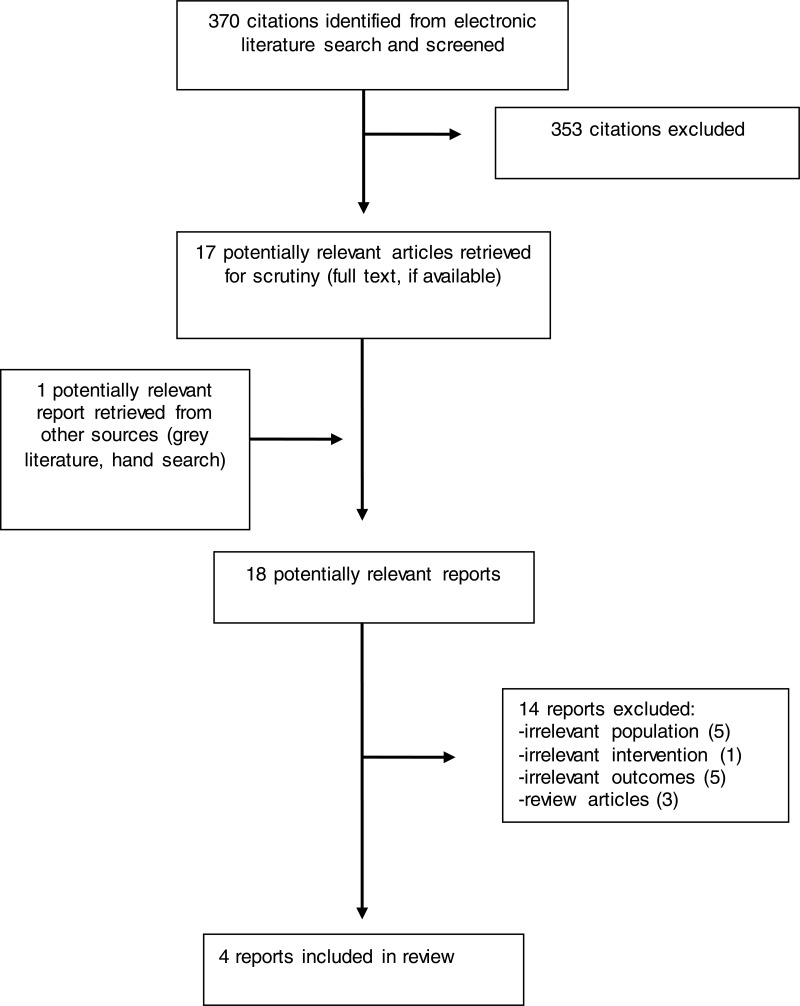

A total of 370 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 353 citations were excluded and 17 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. One potentially relevant publication was retrieved from the grey literature search. Of these potentially relevant articles, 14 publications were excluded for various reasons, while four publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 describes the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection.

Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are presented by study type in Appendix 2.

1. What is the clinical effectiveness of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms?

Study Design

One RCT with a double-blind crossover design16 and two non-randomized studies17,18 were identified for this research question. One of the non-randomized studies was a retrospective chart review17 and one was a retrospective cohort study18 based on post-hoc analysis of an RCT.

Country of Origin

The identified RCT was conducted in Germany16 and the retrospective chart review and cohort study were conducted in the US.17,18

Patient Population

The RCT studied two separate groups: one group of major depressive disorder (MDD) in-patients and one group of healthy volunteer patients (n = 20 in each group).16 The cohort study focused on adult in-patients with opioid addiction undergoing methadone-based detoxification who were nicotine-dependent (n = 96).18 The patients were at a single centre allowing cigarette smoking during the detoxification program.18 The retrospective chart review studied veterans and active duty soldiers at a single hospital who were diagnosed with PTSD and prescribed medication for combat nightmares associated with PTSD (478 individual patient prescription regimens in 327 patients; 27 prescription regimens with clonidine).17

Interventions and Comparators

Patients in the RCT first received a single 0.15 mg dose of clonidine or placebo and then received the other treatment one week later.16 The retrospective chart review of patients with PTSD combat nightmares included 27 individual prescription regimens or trials of clonidine with dosages ranging from 0.1 mg to 4.0 mg per day and maximum prescription lengths ranging from two to 1216 days.17 Each trial consisted of medication use at a constant dosage until the dosage was changed or stopped and multiple trials may have been conducted in a one or more patients prescribed clonidine.17 The other medications and medication combinations prescribed for combat nightmares were: prazosin, terazosin, risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, perphenazine, trazodone, mirtazapine, prazosin and trazodone, and prazosin and quetiapine.17 The retrospective cohort study included patients grouped according to whether patients received naltrexone or placebo and whether they received clonidine or not (n = 96).18 Patients given clonidine received a flexible dose of 0.1 mg to 0.2 mg every six hours.18

Outcomes

The RCT studied working memory using a word suppression test with neutral and negative valenced words and tested memory retrieval based on recall of events prior to the day before testing.16 Working memory and memory retrieval tests were conducted in patients one hour after treatment administration.16 To test memory consolidation, wordlist learning was performed 15 minutes prior to treatment and word recall was performed 24 hours after treatment.16 The retrospective chart review on treatment of combat nightmares classified response to treatment as one of the following: no change in combat nightmares (no response), decrease in frequency and severity of combat nightmares (partial response), and total suppression of combat nightmares (full response).17 The retrospective cohort study evaluated cigarette smoking through cigarette counts by study staff and daily patient smoking diaries.18 Cigarette craving was assessed through the self-reported Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges which consisted of five items describing the rewarding properties of smoking and five items describing relief from negative effects.18 Both outcomes were measured on each day of the six-day detoxification program.18

2. What are the harms associated with the potential misuse or abuse of clonidine?

Study Design

One retrospective chart review was identified.19

Country of Origin

The retrospective chart review was conducted in Australia.19

Patient Population

The retrospective chart review studied patients over 15 years old admitted to a single hospital toxicology unit for clonidine overdose or poisoning (n = 119).19

Interventions and Comparators

The chart review of patients who overdosed on clonidine studied separate groups of patients based on whether clonidine ingestion was acute (n = 108; median dose of 2.1 mg; range of 0.4 mg to 15 mg) or staggered (n = 11; median dose of 3.6 mg; dose range of 1.5 mg to 30 mg; ingestion period range of 0.5 days to seven days) and whether there were co-ingestants (benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and alcohol) or not.19 In patients with acute clonidine ingestion, 40 had ingested clonidine alone and 68 had ingested clonidine with another drug or substance.19 Out of the 11 patients with staggered clonidine ingestion, 10 ingested another drug.19

Outcomes

The retrospective chart review on clonidine overdose studied the following outcomes: bradycardia (heart rate < 60 beats per minute) and its duration, hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg) and its duration, hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg), Glasgow coma score, hypothermia, arrhythmia, death, and administration of and response to antidote treatment (e.g., naloxone or atropine).19 Associations of clonidine dose with minimum heart rate, minimum systolic blood pressure, and Glasgow coma score were also analyzed.19

3. What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of clonidine for the treatment of psychiatric conditions or symptoms in adults?

No relevant evidence-based guidelines were identified.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the critical appraisal of included publications are presented by study type in Appendix 3.

1. What is the clinical effectiveness of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms?

In the RCT,16 the hypotheses, main outcomes, characteristics of included patients, interventions, and findings were clearly described. Risk of bias from randomization, allocation, blinding, attrition, and selective reporting was low. The memory tests used to measure the outcomes were developed by the authors, with previous publications being cited, and information on the validity and reliability of the tests was not provided. Estimates of random variability and actual P values were reported for the main outcomes. The statistical tests were appropriate and post-hoc analyses were clearly identified. Treatment order was not controlled for in the analyses of the outcomes, meaning that factors such as previous test practice during evaluation of the second treatment were not taken into account. Sample size calculations were not provided. Generalizability is limited as a single dose of clonidine is not representative of clonidine treatment in clinical practice. Also, it was unclear whether the included MDD patients and healthy volunteers were representative of their respective source populations as details on recruitment of MDD in-patients were not provided and patients with psychiatric co-morbidities were excluded. Healthy volunteers were recruited through local advertisements without further details given.

The retrospective chart review17 in patients with combat nightmares clearly described the study objectives, main outcomes, characteristics of included patients, and main findings and the study patients were representative of their source population as all records from patients initially examined during a one year period were assessed for the study criteria. Comparisons between different interventions were not tested. Medication trials were not all independent of one another (multiple trials in some patients) and treatment compliance was not reported. Response to one medication regimen in a patient may have predicted response to a different dosage or medication in the same patient and differences in treatment compliance between medications may affect observed responses. Response of frequency and severity of combat nightmares to treatment was not assessed using a valid and reliable instrument and estimates of random variability in treatment response were not provided.

In the retrospective cohort study,18 the main outcomes, characteristics of included patients, and interventions of interest were clearly described. However, the hypotheses and main findings were not clearly described. The post-hoc nature of the study was clearly stated, the outcome measures used were valid and reliable, the statistical tests used to assess the main outcomes were appropriate, and follow-up period was the same for all patients. However, information was not available on principle confounders (such as smoking and smoking cessation history), effect sizes, simple outcome data, random variability of the main outcomes, losses to follow-up, actual P values, and statistical power. There was no adjustment for confounding in the analyses. The study patients represented only one centre in the original multi-centre RCT and were originally selected based on opioid addiction rather than nicotine dependence. Also, the staff and facility were not representative of interventions for smoking cessation alone. The results are not generalizable outside of the in-patient opioid detoxification setting.

2. What are the harms associated with the potential misuse or abuse of clonidine?

The retrospective chart review19 clearly described the study objectives, main outcomes, characteristics of included patients, and main findings. The study population was representative of the source population, as all patients admitted over an 18-year period to a single toxicology unit for clonidine overdose or poisoning were included. All analyses were pre-specified in the methods and the outcome measures were valid and reliable. Estimates of random variability were provided for the continuous outcomes but not the dichotomous outcomes. It is unclear whether linear regression analysis was appropriate for testing associations of minimum heart rate, minimum systolic blood pressure, and Glasgow coma score with dose and there was no adjustment for confounders such as underlying medical conditions. Also, ingested doses of clonidine and presence of reported co-ingestants were not confirmed by laboratory analysis.

Summary of Findings

More detailed results from included publications are presented by study type in Appendix 4.

1. What is the clinical effectiveness of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms?

One RCT16 studying the effects of clonidine on memory, one retrospective chart review17 studying medications for the treatment of combat nightmares in patients with PTSD, and one retrospective cohort study18 on smoking cessation in patients with opioid addiction undergoing a detoxification program provided information on the clinical effectiveness of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms.

The RCT16 found that in both healthy volunteer and MDD patients, a single dose of clonidine decreased memory consolidation one day later compared with placebo (approximately 8% to 9% absolute reduction in words recalled; P = 0.034) and had no statistically significant effect on working memory and memory retrieval one hour after dosing compared with placebo. The effect size of clonidine versus placebo was not statistically significantly different between the healthy volunteer and MDD patients.

The chart review17 reported that clonidine was effective in reducing the frequency and/or severity of PTSD combat nightmares in 17 out of the 27 medication trials (63%) evaluated, with dosages ranging from 0.1 mg to 2.0 mg per day. Dosages ranged from 0.1 mg to 4.0 mg per day for patients who reported no response. None of the patients prescribed clonidine achieved full suppression of combat nightmares. Of the six other medications prescribed in 20 or more trials, only risperidone had a higher success rate (51% with partial response and 26% with full response). However, statistical analysis was not performed on the results and there may have been underlying differences between patients prescribed different medications due to the lack of randomization.

The results from the retrospective cohort study18 suggested that addition of clonidine to the opioid detoxification program for nicotine-dependent patients already taking naltrexone decreased smoking and cigarette craving. Repeated measures ANOVA of the smoking assessment repeated over six days indicated that the clonidine and naltrexone treatment compared with naltrexone alone decreased the number of cigarettes smoked per day (P < 0.02) and cigarette craving (P < 0.01). Estimates of differences in cigarettes smoked and cigarette craving between patients on naltrexone with and without clonidine treatment were not available. The addition of clonidine to placebo did not have a significant effect on smoking or cigarette craving, indicating that benefits were only observed in patients already receiving naltrexone for opioid withdrawal.

2. What are the harms associated with the potential misuse or abuse of clonidine?

One retrospective chart review19 studied harms associated with the potential misuse or abuse of clonidine. Several outcomes were reported in patients who had been admitted for clonidine overdose. Symptoms of overdose were seen in greater proportions of patients who ingested clonidine alone compared with patients who took a co-ingestant (see Appendix 4 for results broken down by these categories).

The Glasgow coma score was less than the maximum score of 15 in 68% of patients with acute clonidine ingestion and was less than nine in 9% of patients. Patients who took a coingestant and had a Glasgow coma score of less than nine had all ingested a benzodiazepine with clonidine. A score of less than 15 indicates a patient unable to perform at least one of the following: spontaneously open eyes, obey verbal commands through motor responses, or appear oriented and converse.20 A score of less than nine corresponds to a condition serious enough to warrant intubation.20 The remaining 32% of patients had the maximum score of 15, indicating they were fully awake.

In patients who took clonidine alone, minimum heart rate was significantly associated with clonidine dose, with an effect of –0.002 beats per minute / µg of clonidine (standard error of 0.001, P = 0.02). Bradycardia (heart rate < 60 beats per minute) was observed in 76% of patients, with a median duration of 20 hours. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg) was reported in 24% of patients, with a later median onset and shorter median duration in patients who took a co-ingestant compared with patients who took clonidine alone. There was no statistically significant association of Glasgow coma score or minimum systolic blood pressure with clonidine dose. Severe hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg) occurred in two patients, both of whom had taken a co-ingestant. Early hypertension was reported in 3% of patients, all of whom took a dose of clonidine (eight to 12 mg) much greater than the median dose of 2.1 mg. A definition for early hypertension was not specified. Miosis was present in 29% of patients and hypothermia was present in 10% of patients.

In terms of interventions for acute overdose, 24% of patients were admitted to the intensive care unit, with 11% of patients being intubated and 22%, 21%, and 7% of patients being treated with activated charcoal, naloxone, and atropine, respectively.

In 11 overdose patients who had taken clonidine in staggered doses, bradycardia was present in 91% of patients, hypotension was present in 27% of patients, and a Glasgow coma score of less than 15 was present in 36% of patients. One patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for cardiac monitoring, two patients were given naloxone, and one patient was given atropine. No arrhythmias or deaths occurred in patients taking either an acute or staggered dose of clonidine.

3. What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of clonidine for the treatment of psychiatric conditions or symptoms in adults?

No relevant evidence-based guidelines were identified.

Limitations

Four studies relevant to the use of clonidine for psychiatric conditions or symptoms or the misuse of clonidine in adults were identified and three of the studies had sample sizes of less than 120 patients. The fourth study was a chart review including 327 patients total, with 27 patients or fewer being prescribed clonidine.17 Also, all of the studies were single centre studies and none were conducted in Canada, limiting the generalizability of the results to the Canadian setting.

The RCT examined the short term (24 hour) effects of a single dose of clonidine, which is not representative of clonidine treatment in clinical practice.

In the chart review of medications for PTSD combat nightmares, compliance with prescribed medication was not reported and multiple medication trials that were conducted within some patients would not have been independent of one another. Statistical comparisons between clonidine and other treatments were not performed. Comparisons would not have been appropriate due to the above-mentioned limitations as well as potential differences among groups of patients prescribed each medication. Study inclusion was limited to veteran and active duty soldiers with combat nightmares and it is unclear whether the results would be relevant for patients with other types of PTSD nightmares.

The retrospective cohort study in smokers undergoing opioid detoxification did not adjust for confounders and did not report effect sizes. The patient sample was not representative of the original study population (opioid withdrawal patients) and the results are only applicable to patients undergoing voluntary smoking cessation and in-patient opioid detoxification simultaneously.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

A total of four relevant publications were identified, including one RCT,16 one retrospective cohort study,18 and two retrospective chart reviews.17,19 The RCT,16 retrospective cohort study,18 and one of the retrospective chart reviews17 studied the clinical effects of clonidine for the treatment of adults with psychiatric conditions or symptoms. One of the chart reviews studied harms associated with the potential misuse and abuse of clonidine.19 No relevant evidence-based guidelines were identified. There were no large-scale studies (sample sizes were less than 120) and the small number of relevant studies meant that definitive conclusions could not be drawn.

The evidence for clinical benefits of clonidine treatment was limited by the retrospective nature of two of the relevant studies.17,18 Clonidine at a dosage of 0.1 mg to 2.0 mg per day may be effective in reducing the frequency and/or severity of PTSD combat nightmares, though statistical comparisons with other medications, placebo, or no treatment were not available.17 Flexible dose clonidine (0.1 mg to 0.2 mg every six hours) may be effective in reducing cigarettes smoked and smoking craving in nicotine-dependent in-patients undergoing methadone-based opioid detoxification and receiving low-dose naltrexone.18 However, the effect size was not reported.18 Memory consolidation may be negatively affected by clonidine, though the single dose studied in the RCT was not representative of clonidine treatment.16

Harms observed in clonidine overdose patients included impaired consciousness, miosis, hypothermia, bradycardia, hypotension, and severe hypertension and clonidine dose may be associated with decreased minimum heart rate.19

While the use of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists, including clonidine, has been studied in the pediatric population for the treatment of ADHD, tic disorders, and Tourette syndrome,2,6 none of the identified studies pertained to these conditions in the adult population. One study provided information on harms associated with clonidine overdose,19 but studies of chronic abuse or misuse of clonidine were not identified.

References

- 1.

- Sica DA. Centrally acting antihypertensive agents: an update. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007 May; 9(5):399–405. [PMC free article: PMC8110163] [PubMed: 17485976]

- 2.

- Naguy A. Clonidine Use in Psychiatry: Panacea or Panache. Pharmacology. 2016;98(1-2):87–92. [PubMed: 27161101]

- 3.

- PrMint-clonidine, clondidine hydrochloride tablets, USP 0.1 and 0.2 mg, antihy pertensive [product monograph] [Internet]. Mississauga (ON): Mint Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2017 Mar 8. [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://pdf

.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00038468.PDF - 4.

- PrTeva-clonidine (clondidine hydrochloride): USP tablets, 0.025 mg, v ascular stabilizer for the treatment of menopausal flushing [product monograph] [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Teva Canada Limited; 2016 Feb 6. [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Av ailable from: https://pdf

.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00023909.PDF - 5.

- Giovannitti JA, Jr., Thoms SM, Crawford JJ. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists: a review of current clinical applications. Anesth Prog [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 23];62(1):31–9. Available from: http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pmc/articles/PMC4389556 [PMC free article: PMC4389556] [PubMed: 25849473] - 6.

- Quezada J, Coffman KA. Current Approaches and New Developments in the Pharmacological Management of Tourette Syndrome. CNS Drugs [Epub ahead of print]. 2018 Jan 15. [PMC free article: PMC5843687] [PubMed: 29335879]

- 7.

- Belkin MR, Schwartz TL. Alpha-2 receptor agonists for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Drugs Context [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 23];4:212286. Available from: http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pmc/articles/PMC4544272 [PMC free article: PMC4544272] [PubMed: 26322115] - 8.

- Seale JP, Dittmer T, Sigman EJ, Clemons H, Johnson JA. Combined abuse of clonidine and amitripty line in a patient on buprenorphine maintenance treatment. J Addict Med [Internet]. 2014 Nov 5 [cited 2018 Jan 23];8(6):476–8. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4227908/ [PMC free article: PMC4227908] [PubMed: 25314340] - 9.

- Schindler EA, Tirado-Morales DJ, Kushon D. Clonidine abuse in a methadone-maintained, clonazepam-abusing patient. J Addict Med. 2013;7(3):218–9. [PubMed: 23519051]

- 10.

- Gahr M, Freudenmann RW, Eller J, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C. Abuse liability of centrally acting non-opioid analgesics and muscle relaxants--a brief update based on a comparison of pharmacov igilance data and evidence from the literature. Int J Neuropsy chopharmcol. 2014 Jun;17(6):957–9. [PubMed: 24552880]

- 11.

- Pharmacologic management of patients with ADHD: a review of guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2016 Mar 18. (CADTH Rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal). [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmedhealth /PMH0086535/pdf/PubMedHealth _PMH0086535.pdf [PubMed: 27077160] - 12.

- Treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, operational stress injury, or critical incident stress: a review of guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2015 Apr 27. (CADTH Rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal). [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmedhealth /PMH0078541/pdf/PubMedHealth _PMH0078541.pdf - 13.

- Tricyclic antidepressants, clonidine, v enlafaxine, and modafinil for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a review of the clinical evidence [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2013 Mar 21. (CADTH Rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal). [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www

.cadth.ca /sites/default/files /pdf/htis/apr-2013/RC0440 %20Non-stimulant %20and%20modafinil%20therapy %20for%20ADHD%20final.pdf - 14.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Feb 20];358:j4008. Available from: http://www

.bmj.com/content/bmj/358/bmj .j4008.full.pdf [PMC free article: PMC5833365] [PubMed: 28935701] - 15.

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health [Internet]. 1998 Jun [cited 2018 Feb 20];52(6):377–84. Available from: http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pmc/articles /PMC1756728/pdf/v052p00377.pdf [PMC free article: PMC1756728] [PubMed: 9764259] - 16.

- Kuffel A, Eikelmann S, Terfehr K, Mau G, Kuehl LK, Otte C, et al. Noradrenergic blockade and memory in patients with major depression and healthy participants. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014 Feb;40:86–90. [PubMed: 24485479]

- 17.

- Detweiler MB, Pagadala B, Candelario J, Boyle JS, Detweiler JG, Lutgens BW. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder nightmares at a veterans affairs medical center. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2016 Dec 16 [cited 2018 Jan 23];5(12):pii: E117. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5184790/ [PMC free article: PMC5184790] [PubMed: 27999253] - 18.

- Mannelli P, Wu LT, Peindl KS, Gorelick DA. Smoking and opioid detoxification: behavioral changes and response to treatment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013 Oct;15(10):1705–13. [PMC free article: PMC3768333] [PubMed: 23572466]

- 19.

- Isbister GK, Heppell SP, Page CB, Ryan NM. Adult clonidine overdose: prolonged brady cardia and central nervous system depression, but not severe toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017 Mar;55(3):187–92. [PubMed: 28107093]

- 20.

- Bordini AL, Luiz TF, Fernandes M, Arruda WO, Teive HA. Coma scales: a historical review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010 Dec [cited 2018 Feb 20];68(6):930–7. Available from: http://www

.scielo.br/pdf/anp/v68n6/19 .pdf [PubMed: 21243255]

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2

Characteristics of Included Randomized Clinical Trial.

Table 3

Characteristics of Included Non-Randomized Clinical Studies.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4

Strengths and Limitations of Randomized Controlled Trial Using the Downs and Black Checklist.

Table 5

Strengths and Limitations of Non-Randomized Studies Using the Downs and Black Checklist.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Author’s Conclusions

Table 6

Summary of Findings of Included Randomized Controlled Trial.

Table 7

Summary of Findings of Included Non-Randomized Studies.

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Case Reports

- Cuadra RH, White WB. Severe and refractory hypertension in a young woman. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016 Jun;10(6):506–9. Available from: http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pubmed/27160032 [PMC free article: PMC4905787] [PubMed: 27160032] - Seale JP, Dittmer T, Sigman EJ, Clemons H, Johnson JA. Combined abuse of clonidine and amitriptyline in a patient on buprenorphine maintenance treatment. J Addict Med. 2014 Nov;8(6):476–8. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmed/25314340 [PMC free article: PMC4227908] [PubMed: 25314340] - Pomerleau AC, Gooden CE, Fantz CR, Morgan BW. Dermal exposure to a compounded pain cream resulting in severely elevated clonidine concentration. J Med Toxicol. 2014 Mar;10(1):61–4. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmed/24129834 [PMC free article: PMC3951633] [PubMed: 24129834] - Schindler EAD, Tirado-Morales DJ, Kushon D. Clonidine abuse in a methadone-maintained, clonazepam-abusing patient. J Addict Med. 2013;7(3):218–9. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmed/23519051 [PubMed: 23519051]

Irrelevant Outcomes

- Tamburello AC, Kathpal A, Reeves R. Characteristics of inmates who misuse prescription medication. J Correct Health Care. 2017;23(4):449–58. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmed/28884614 [PubMed: 28884614] - Gahr M, Freudenmann RW, Eller J, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C. Abuse liability of centrally acting non-opioid analgesics and muscle relaxants--a brief update based on a comparison of pharmacovigilance data and evidence from the literature. Int J Neuropsychopharmcol. 2014 Jun;17(6):957–9. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pubmed/24552880 [PubMed: 24552880]

About the Series

Version: 1.0

Suggested citation:

Clonidine for the Treatment of Psychiatric Conditions and Symptoms: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, and Guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2018 Feb (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.

The copyright and other intellectual property rights in this document are owned by CADTH and its licensors. These rights are protected by the Canadian Copyright Act and other national and international laws and agreements. Users are permitted to make copies of this document for non-commercial purposes only, provided it is not modified when reproduced and appropriate credit is given to CADTH and its licensors.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/