Alcohol: Social damages, abuse, and dependence

Authors

INSERM Collective Expertise Centre.This document presents the summary and recommendations of the group of experts assembled by Inserm as part of the collective expertise procedure in response to the questions raised by the Mission interministérielle de lutte contre la drogue et la toxicomanie (MILDT; the interministerial anti-drug and drug-addiction mission), the Caisse nationale d'assurance maladie des travailleurs salariés (CNAMTS; the national sickness insurance scheme for salaried employees), and the Institut national de prévention et d'éducation pour la santé (INPRES; national institute for prevention and health education (an example is CFES, Comité français d'éducation pour la santé French health education committee)) on consumption habits, social damage, and alcohol abuse and dependency.

The Centre d'expertise collective de l'Inserm (Inserm collective expertise centre) has coordinated this collective expertise strategy with the Département animation et partenariat scientifique (DAPS; leadership and scientific partnership department) for dossier compilation in conjunction with the service of documentation from the Département de l'information scientifique et de la communication (DISC; documentation sector of the scientific information and communication department) as regards the bibliographical research.

Foreword

Alcohol consumption has regularly decreased in recent decades both in France and in Europe as a whole. France nevertheless continues to lead the European states in terms of premature, alcohol-related male deaths. Alcohol abuse is still a major public health problem in France.

Despite a certain harmonisation in Western countries, drinking habits are still firmly steeped in local culture. The type of drinks (wine, beer, spirits) and consumption habits (daily, occasional, massive intake and drunkenness) vary according to age, sex, and social and cultural environment. The hazards are not the same: accidents, impulsive, risky behaviour, violence and trauma associated with drunkenness; cancer, cirrhosis, cardiovascular complications, neurological disorders and dependency associated with excessive chronic alcohol intake. Five million French people currently have first-hand experience with the medical problems and psychological or social difficulties associated with alcohol abuse.

The steps taken to solve this problem still appear inadequate. Despite the Évin Law of 1991, exceptions to the advertising ban on alcoholic drinks have multiplied. Preventive and anti-drunk-driving campaigns have had little impact to date. Inadequately trained, general practitioners rarely broach the subject of alcohol consumption with their patients and rarely apply screening procedures. Despite the well-publicised desire to make combating the harmful effects of alcohol a public health priority, there is still an obvious lack of resources for both the prevention and management of this problem.

The Mission interministérielle de lutte contre la drogue et la toxicomanie (MILDT), the Caisse nationale d'assurance maladie des travailleurs salariés (CNAMTS), and the Institut national de prévention et d'éducation pour la santé (INPES; for example CFES, Comité français d'éducation pour la santé), who are the key players in public policies for the prevention and management of alcohol-related problems, wanted to question Inserm via the collective expertise procedure. This expertise, which continues an initial approach dealing more specifically with the effects of alcohol on health, will provide validated scientific information relating to alcohol-related consumption habits and how these have changed over time, the social damages associated with excessive consumption, the risk factors for abuse and dependency, and the related management problems.

To carry out this second expert appraisal of alcohol, Inserm has set up a multidisciplinary group of experts in the fields of epidemiology, human and social sciences, road safety, psychiatry, and biology. The expert group focused on the following questions:

- What information is available with regard to changes in alcohol consumption over the last 20 years in France and throughout the world? What main trends can be identified in France?

- What information is available regarding the social usage of alcohol (in professional situations as well as in social gatherings with family and friends, etc.)? What is known about the phenomenon of multiple consumption?

- What information is available relating to the social damages associated with excessive alcohol consumption in terms of accidents (accidents at work, road-traffic accidents, domestic), violence, delinquency, and marginalisation?

- What information is available regarding steps to prevent alcohol-related behaviour and what is the outcome of such an approach, especially in adolescents and young adults?

- What information is available regarding the prevalence of alcohol abuse and dependency? What tools are available to identify patients with alcohol-related problems?

- What are the underlying mechanisms involved in alcohol dependency? What is known about the interaction of these mechanisms with risk or protection factors (individual susceptibility, environmental factors)?

- What is the stance of the health authorities in relation to alcohol-dependent diseases? How can the efficacy of the management strategies be assessed?

Over 2,000 articles were selected after searching international databases. During the eight working sessions organised between September 2001 and July 2002, experts presented a critical analysis and a summary of published international and national studies on the various aspects of the expertise specification. The last three sessions were devoted to drawing up the main facts and recommendations. Several papers at the end of this investigation will supplement the expert analysis with French data.

Expert advisory group and authors

Group of experts and authors

Philippe ARVERS, Centre de recherche du service de santé des armées, La Tronche, France (research centre of the army medical corps.)

Jean-Pascal ASSAILLY, Institut national de recherche sur les transports et leur sécurité, Arcueil, France (national institute for research into methods of transport and their safety)

Philippe BATEL, Unité de traitement ambulatoire des maladies addictives, Hôpital Beaujon, Clichy, France (outpatient department for addictive diseases, Beaujon Hospital)

Marie CHOQUET, Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Inserm U 472, Villejuif, France

Thierry DANEL, Service d'addictologie, Centre hospitalier régional universitaire de Lille, Lille France (department of addictology, regional university medical centre)

Martine DAOUST, Unité de recherche sur les adaptations physiologiques et comportementales, Université de Picardie, Amiens, France (research unit, physiological and behavioural adaptation, University of Picardy)

Philippe DE WITTE, Biologie du comportement, Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium (behavioural biology, Louvain Catholic University)

Françoise FACY, Epidemiology of addictive behaviour, Inserm XR 302, Le Vésinet, France

Jean-Dominique FAVRE, Psychiatry Department, Hôpital d'instruction des armées

Percy CLAMART, President of the French Alcohology Society

Eric HISPARD, Department of Internal Medicine, Hôpital Fernand-Widal, Paris, France

Thérèse LEBRUN, Centre de recherches économiques, sociologiques et de gestion (CRESGELABORES), Université catholique de Lille, Lille, France (economic, sociological, and management research centre, Lille Catholic University)

Anne-Marie LEHR-DRYLEWICZ, General Practitioner, Parçay-Meslay, France

Michel LEJOYEUX, Psychiatry Department, Hôpital Louis-Mourier, Colombes, France

Pierre MORMÈDE, Laboratoire de neurogénétique et stress, Unité mixte Inra - Université Victor Segalen Bordeaux II, Institut François Magendie, Bordeaux, France (laboratory of neurogenetics and stress, combined unit of Inra and Victor Segalen Bordeaux II University, François Magendie Institute, Bordeaux)

Véronique NAHOUM-GRAPPE, Centre d'études transdisciplinaires, sociologie, anthropologie, histoire, École des hautes études en sciences sociales - CNRS, Paris, France (centre of transdisciplinary studies, sociology, anthropology, and history; school of advanced studies in social science)

Claudine PÉREZ-DIAZ, Centre de recherche psychotropes, santé mentale, société, CESAMES (UMR 8136), CNRS-Université René Descartes Paris V, Paris, France (research centre for psychotropics, mental health and society, CNRS University)

Myriam TSIKOUNAS, Centre d'histoire sociale du XXe siècle/Credhess (UMR 8058), Université Paris I, Paris, France (centre of the social history of the XXth century, University Paris I)

The following participants presented papers

Patrick AIGRAIN, Office national interprofessionnel des vins - Inra, Paris, France (national interprofessional office for wines)

Jean-Michel COSTES, Observatoire français des drogues et des toxicomanies, Paris, France (French observatory for drugs and drug addiction)

Colette MéNARD, Institut national de prévention et d'éducation pour la santé, Vanves, France (national institute of health-related prevention and education) and Stéphane LEGLEYE, Observatoire français des drogues et des toxicomanies, Paris, (French observatory for drugs and drug addiction)

Michel REYNAUD, Département de psychiatrie et d'addictologie, Hôpital Paul-Brousse, Villejuif, France (Department of psychiatry and addictology, Paul-Brousse Hospital)

Jacques WEILL, Honorary University Professor, Tours, France

Marie ZINS, Epidemiology, public health and professional and general environment, Inserm U 88-IFR 69, Saint-Maurice, France

Scientific and editorial coordination

Élisabeth ALIMI, Head of expertise, Centre d'expertise collective de l'Inserm, faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris, France (Inserm collective expertise centre, Xavier-Bichat Faculty of Medicine)

Catherine CHENU, Scientific attaché, Centre d'expertise collective de l'Inserm, faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris, France (Inserm collective expertise centre, Xavier-Bichat Faculty of Medicine)

Jeanne ÉTIEMBLE, Director of the Centre d'expertise collective de l'Inserm, faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris, France (Inserm collective expertise centre, Xavier-Bichat Faculty of Medicine)

Catherine POUZAT, Scientific attaché, Centre d'expertise collective de l'Inserm, faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris, France (Inserm collective expertise centre, Xavier-Bichat Faculty of Medicine)

Bibliographical and technical assistance

Chantal RONDET-GRELLIER, Documentalist, Centre d'expertise collective de l'Inserm, faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris, France (Inserm collective expertise centre, Xavier-Bichat Faculty of Medicine)

Claire NGUYEN-DUY, Proofreader, Paris, France

Summary

The alcohol consumption of a population is generally globally estimated in litres of pure alcohol per inhabitant and per year, regardless of age. Although subject to certain biases, these data can, nevertheless, be used to monitor changes in consumption over time and to make comparisons between different countries.

Although almost all French people consume alcohol, consumption habits vary considerably between young people, who mainly consume alcoholic drinks other than wine on weekends, and people over 65 years of age, who drink mostly wine on a daily basis. Consumer habits also differ between girls and boys and between adult men and women. It is therefore important to consider these various factors in order to define more appropriate prevention strategies.

It is also important to distinguish between the dangers of excessive consumption under certain circumstances, such as when driving, carrying out work-related or domestic tasks (with the ensuing consequences—accidents and acts of violence, etc.), and the longer-term risk associated with chronic consumption. The social costs associated with excessive alcohol consumption compared with health costs indicate that this problem should be considered by linking the two dimensions, namely social and health, in a public health approach that encompasses prevention, care, and social reinsertion.

Global alcohol consumption has fallen from almost 18 litres of pure alcohol per year and per inhabitant in 1960 to almost 11 litres in 1999

Two major sources of data allow alcohol consumption to be estimated on an individual and collective level: market studies and consumer surveys.

Market studies allow global alcohol consumption to be estimated per year and per inhabitant (15 years of age and above) based on the production, importing, and exporting of alcohol. Imports are added to the quantities of alcohol produced per country, and exports are deducted. After weighting according to the size of the population, a mean annual consumption rate per inhabitant is obtained, expressed in litres of pure alcohol.

This is a mean value that does not distinguish between sex, age bracket, socio-professional category, or other sociodemographic criteria. Furthermore, even if this is of little relevance to France, it appears that quite a considerable proportion of alcohol production is not taken into account (not declared and, therefore, not registered). This is particularly evident in the Scandinavian countries and Canada, where it can account for up to 30% of alcohol production.

In France, following an increase between 1951 and 1957, global alcohol consumption fell by almost 40% between 1960 (17.7 litres of pure alcohol/year/inhabitant) and 1999 (10.7 litres). In 20 years, wine consumption has fallen by almost 40% and beer consumption by 15%. The consumption of spirits has also declined (with considerable fluctuations over time). This fall in global alcohol consumption is therefore due essentially to a substantial decrease in the consumption of wine.

In 1999, France ranked in fourth position behind Luxemburg, Ireland, and Portugal. Wine consumption is on the decline in Southern Europe but is increasing very markedly in Northern Europe. The differences in alcohol consumption between the Latin countries, which are traditionally wine producers and consumers, and the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian countries persist but are increasingly less noticeable.

Table

Alcohol consumption1 in France and Europe (World Drink Trends, 2000).

The countries traditionally recognised for their beer and spirits consumption have also witnessed a very rapid growth in their wine consumption, whereas wine-consuming countries have registered an increase in beer consumption. Beer is a newcomer to Mediterranean countries and is mainly consumed by young people. Alcohol consumption in Europe is thus becoming more evenly distributed. However, the increase in beer consumption does not offset the decrease in wine consumption, hence global alcohol consumption is declining.

Some countries around the world have witnessed an increase in their global alcohol consumption (Brazil, Paraguay, Turkey, and Mexico in particular), while others have noted a significant decrease (United States, Chile, Argentina, and Algeria in particular).

Table

Changes in the consumption of wine, beer, and spirits over the last 20 years (World Drink Trends, 2000).

Over 80% of all the alcoholic beverages exported come from European countries. France remains the leading exporter of alcohol (25.9% of the world's trade), while the United States is by far the leading importer.

Consumption surveys highlight indicators that enable homogeneous groups of the population to be followed over time and allow changes in attitude toward alcohol to be studied according to sex, age, and other sociobiographical criteria.

The tools used, the approach adopted, the person carrying out the survey, and the interviewee are all factors that are taken into account when assessing consumption. Depending on the way in which a questionnaire is administered (face to face, over the telephone, or via a self-questionnaire), the information relating to consumption and the level of non-response can vary.

The traditional cause of error mostly observed in consumer surveys is underdeclaration. This can be either intentional, because occasional drinkers have been overlooked, or because the frequency of consumption has, in fact, been underestimated. Consumer surveys therefore underestimate the quantity consumed by 40% to 60%. The response rate to questions asked is lowest for face-to-face surveys, increasing with telephone surveys, and reaching a peak for self-questionnaires (where the relevance of the responses cannot be corrected). However, because the validity of the questionnaires has been assessed in numerous studies over the last 20 years or so, it has come to light that, regardless of the method used to validate them, there is a good correlation between declarations of alcohol consumption.

The data obtained during these surveys show that more men drink than women. They consume alcohol in larger quantities (overall and on separate occasions) and more often than women. They become inebriated more frequently than women. This male-female discrepancy is evident in all international surveys in terms of both quantity and frequency. People tend to drink more frequently as they get older, but consume smaller quantities. This is particularly true of men.

By monitoring subjects in the same cohort over time, a distinction can be made between the specific effect of age and that of belonging to a specific generation. Because it is difficult to study cohorts of individuals over time, “pseudo-cohorts” are formed. These are individuals who, as far as possible, present the same (sex, age bracket, and socio-professional) characteristics.

From 20 years of age, more than one French person in two consumes alcohol at least once a week

In France, the Baromètre santé 2000 1 estimated the daily, weekly, monthly, and more occasional consumption habits of the French population between 12 and 75 years of age.

Among these French people, 3.5% declared that they had never drunk any alcohol in their lives. The proportion of abstainers decreases as a function of age (17% at 12–14 years and almost 2% at 45–54 years). Women abstain more frequently than men.

Over the last 12 months, 90% of the 12–75-year-olds admitted to having drunk at least one alcoholic drink.

Among the 12–75-year-olds, almost 20% admit to drinking alcohol every day—28% of men and 11% of women. This daily consumption pattern starts to appear in young people from the ages of 20–25 years, increasing with age and reaching a peak between 65 and 75 years of age, affecting 65% of men and 33% of women.

Among the 12–75-year-olds, almost 40% admitted to consuming alcohol at least once a week but not every day (44% of men and 34% of women). Weekly consumption is more prevalent among the younger generations and is, indeed, the major consumer trend among the group 20–44 years of age (60% of men and 40% of women). On average, more than one of two French people drink alcohol at least once a week from 20 years of age onward (7 of 10 men and 4 of 10 women). This weekly consumption, however, gives way to daily consumption among the older generations.

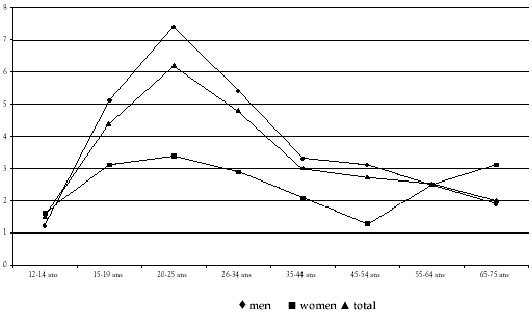

Figure

Alcohol consumption over the last twelve months according to frequency of intake and age (Baromètre santé 2000, CFES).

Figure

Proportion of daily alcohol consumers over the last twelve months according to sex and age (Baromètre santé 2000, CFES).

Of the 12–75-year-olds, 16% admit to consuming alcohol at least once a month but less than once a week. This monthly or occasional consumption mainly concerns young people.

Wine is the most widely consumed alcoholic drink. 17.5% of the 12–75-year-olds consume it on a daily basis (25% of men and 10% of women). This increases with age (62% of men between 65 and 75 years of age and 32% of women in the same age bracket).

Figure

Daily consumption of various types of alcoholic beverage over the last twelve months, according to age bracket (Baromètre santé 2000, CFES).

Daily beer consumption concerns almost 3% of the 12–75-year-olds (5% of men and 0.5% of women). Weekly consumption is most frequent. Only 0.8% of the 12–75-year-olds consume spirits on a daily basis. This is essentially limited to men over 45 years of age. Weekly, monthly, or occasional consumption is the most frequent, with each category concerned with approximately 19% of the 12–75-year-olds.

Generally speaking, weekend consumption is higher (in terms of variety and quantity of drinks) than during the week for all age brackets and for both sexes. This particular trait certainly helps to explain why inebriation is more common among weekly consumers (young people between 18 and 25 years of age drink 5.6 glasses on a Saturday compared with 1.9 glasses in the case of the over 55-year-olds) than among daily consumers who, on average, drink more.

Table

Average number of glasses drunk in an evening according to socio-professional category (Baromètre santé 2000, CFES).

The average number of glasses drunk in an evening is higher in the "craftsmen, tradesmen and Company Director" category (averaging 3.4 glasses).

Inebriation is most commonplace among young people. The difference between the sexes is most apparent in the 20–25 age bracket: 40% of men between the ages of 20 and 25 repeatedly become drunk (more than three times per year) compared with 24.5% of women in this particular age bracket.

Figure

Average number of cases of inebriation over the last 12 months per sex and per age (Baromètre santé 2000, CFES).

Interviews during which people were asked about their risk of alcohol dependency, both past and present, show that 1 of 10 adults is affected, men being involved three times more often than women (13.5% versus 4%); the difference between the sexes increases with age.

Although the Baromètres santé (surveys) of 1992, 1995, and 2000 were modified in the questionnaires, some indicators can be compared. A slight decrease in consumption frequency and the quantity consumed can be noted for men and women over 20 years of age. On the other hand, changes in terms of inebriation are not significant.

In the working environment, men drink twice as much alcohol as women

In France, several studies have been carried out in recent years to assess the prevalence of alcohol consumption in the working environment. First and foremost, it should be noted that the collection of objective and systematic data is ethically difficult within the scope of occupational medicine. Furthermore, it should also be noted that acceptable blood alcohol levels change over time—not least by current legislation for road users—which is 0.5 g/l at the present time (law dated 13 November 1996).

According to an IPSOS survey conducted in September 2001, 71% of those interviewed consume alcohol during business lunches/dinners, with 35% consuming more alcohol than usual. Alcohol consumption in a professional context is evident in physically demanding professions, such as building, farming, and maintenance works, as well as in professions dealing with the general public.

On the basis of a 1999 study involving work doctors in the Paris region, almost one of four employees regularly consumes alcohol at work with colleagues or clients.

In all cases and regardless of age, the average number of glasses consumed by men in a working environment is 1.5 to 2 times higher than that of women. According to the results of the Gazel cohort study (over 20,000 EDF-GDF (gas and electricity) employees), 18.3% of men admitted to drinking 3 to 4 glasses of alcohol every day and 12.3% of men admitted to 5 glasses and more per day. The equivalent percentages in women are 3.5% and 1.2%, respectively.

Surveys carried out by teams of work doctors have also facilitated assessment of the number of people experiencing alcohol-related problems. In the iron and steel sector, doctors confirmed in 1983 that 10% of workers were excessive drinkers and 8% alcoholics. In Lorraine, the occupational medicine departments estimated in 1983 that 3% of the workforce were excessive drinkers and alcoholics. As regards a sample of national defence workers, doctors found that 15% were excessive drinkers and 7% alcoholics in 1989. A 1991 survey conducted in a postal sorting centre revealed that 16% of employees drank to excess, whereas 8% were alcoholics. In 1997, a survey focusing on the workforce in the municipality of Saint-Étienne revealed that 10% were alcohol dependent. The inter-company survey conducted in 1997 in Lower Normandy showed that 3.4% of the employees had been identified as excessive drinkers and 1.1% as alcoholics. These figures can be compared against those recorded in an initial survey carried out in this same region in 1980 in which 8% of the workforce were alcoholics. The survey carried out in 1991 found that 3% drank to excess and 2% were alcoholics. According to the most recent survey, almost all professional sectors are affected by excessive alcohol consumption, although the building-public works' sector remains particularly susceptible.

In young people, repeated bouts of inebriation are often associated with regular alcohol or cannabis consumption

On the basis of surveys conducted in French schools between 1993 and 1999 (ESPAD 2 ), experimenting with alcohol has slightly increased in France, rising from 81% to 86% in 16-year-old boys and from 79% to 85% in girls of the same age. Repeated usage (at least 10 uses in the course of one month) does not appear to have increased. As regards inebriation, the number of young people who, between 1993 and 1999, admitted to having experienced at least 10 episodes of drunkenness over a 12-month period has remained stable in the 14–16-year-old bracket (5% in the boys) but has slightly fallen among the 17- and 18-year-olds (from 14% to 10% in boys 18 years of age and from 3% to 2% in girls of the same age).

In 1999, the proportion of French pupils who consumed alcohol during the previous 12 months was below the average figure obtained for all European countries (77% versus 83%). The same applied to the proportion of French pupils who had been inebriated in the last 12 months (36% versus 52%).

The French survey, ESCAPAD, 3 shows that 17-year-old girls had their first taste of alcohol at 13.6 years, i.e., on average 6 months later than boys (13.1 years). Alcohol preceded smoking. The first experience of inebriation occurred approximately 2 years after initial alcohol consumption, regardless of age and sex. Girls declared having been inebriated for the first time on average 5 months after boys of their own age.

Table

The frequency of alcohol consumption over the last 30 days in 17-year-old girls and boys between 17 and 19 years of age (Escapad 2000, OFDT).

Behaviour differs between the sexes. The prevalence of smoking, alcohol consumption, and inebriation appears to be linked to the early onset of experimentation. As regards concomitant usage, cannabis and alcohol are mostly linked.

Table

Frequency of inebriation throughout life (Escapad 2000, OFDT).

According to longitudinal studies conducted in the United States and Europe focusing on adolescent alcohol consumption, the first risk factor for consumption, at the end of adolescence or the onset of adulthood, is the early onset of consumption. The onset of alcohol consumption at 12–14 years of age is a predictive factor for alcohol consumption at 16 years of age or even alcohol abuse, whereas the onset of alcohol consumption at 16 years of age is marginally predictive for adult consumption. This applies to both boys and girls.

One-third of young people between 16 and 17 years of age has experimented with alcohol, smoking, and cannabis. There is a gradual shift toward experimenting with one or even two substances, followed by all three substances.

One young person in five regularly uses one of these substances. Polyconsumption increases appreciably with age, especially in the case of 19-year-old boys, 14% of whom take several substances on a regular basis.

Outings and evening functions are a fundamental aspect of a young person's life and often lead to alcohol consumption. However, being a consumer may entice a young person to go to functions. According to Escapad, young people who frequent "techno" events account for less than 1% of the study population. Consequently, most of the alcohol consumers, smokers, and people who become inebriated are recruited from among youngsters who have never been to a "techno" event.

The correlation (measured by the odds ratio(OR)) between the regular consumption of cannabis and regular alcohol consumption or smoking is high (3 < OR > 5) for boys and even higher (OR > 5) for girls. For both males and females, the link between repeated inebriation and regular alcohol or cannabis consumption is very marked. It is, however, more marked for girls than for boys. Overall, the risk of regular cannabis consumption is higher among female smokers than male smokers and among female drinkers than male drinkers. The risk of having been inebriated several times over the last 30 days is higher in girls who consume alcohol on a regular basis or take cannabis than among boys with similar habits.

Certain sociodemographic and educational factors are more closely linked with a high alcohol consumption. The same applies to absenteeism from school. The pupil's behaviour at school (absenteeism, school results, and liking for school) is more closely linked with alcohol consumption than familial characteristics ("intact", single-parent, restructured family), regardless of the type of school establishment (priority education area, public, private, town, or rural location). Violent, delinquent behaviour (major violence, theft, and disputes), running away, and attempted suicide are associated with regular alcohol consumption. Consumption is not linked more frequently with major violence than it is with other problems, such as attempted suicide or running away. The links between regular consumption and risky behaviour are always more noticeable for girls than for boys. Finally, those who do not practise any sport or who practise for more than 8 hours per week are more likely to become regular consumers of alcohol than others.

Alcohol plays a key role in the contemporary youth party scene

The creation of a social link often implies gestures that ritualise alcohol consumption in our society: drinking is a must to celebrate a financial market or a sporting or professional success. Festive drinking, i.e., that which implies excess as standard, is required to mark a change in lifestyle (a birth, a marriage, a retirement, a move) or Christmas/New Year festivities. This drinking tradition pervades individual space, private moments, and the collective social scene. Drinking is an invitation to enforce this social link. But “excessive drinking” also implies “social unhappiness” in our culture and is often associated with an unhappy love affair or images of economic and social decline. The social function of drinking is heightened by that of its economy. The alcohol trade, in all its forms, comes from a long history of wine and is characterised by resistance to historical and social change, to wars and periods of recession. The need for social drinking firmly consolidates a market that has been extended worldwide for more than 20 centuries. Investigating alcohol in public health terms involves identifying this historical, economical, and sociological focus for social drinking.

How have the consumption habits of today's youth changed? The quality of preventive messages is linked with this awareness.

At the end of the 19th century, writers of folklore and romantic interludes between girls and boys in conventional French societies explained that ways of celebrating, gestures and attitudes, excesses and boundaries for transgression are coded by the community. In fact, these traditions, customs, habits, and codes define parameters for the young people of the village, for the environment, and for close relationships between young people allowing them to choose their partners with or without parental consent. In this culture, sexual restrictions must be maintained, especially for the girls. Young people must therefore obtain permission and are subject to collective constraints before going off to party.

Nowadays, trends relating to going out and different types of “partying” are constantly changing among young people in favour of an urbanised lifestyle, even in the countryside, where the emphasis is on freedom and mobility. Today, festive occasions differ in terms of what to wear (party clothes or not), the venues, itinerary (drinking, dancing, singing, eating and hanging around, etc.), the pace and time-scale which tend to invade the week and to “fall” toward the end of the night or sometimes the next day. The choice is no longer a party, but three or four “bars” or “nightclubs” between which young people flit to and fro at top speed. They sometimes choose the town pavement to party, like in Madrid, along the lines of “Botellon”.

Drinks are being invented all the time, with unprecedented names and blends of ingredients. Overconsumption intervenes at every stage through the evening, from planning the evening ahead through to the last drop consumed in the small hours of the morning. Alcohol consumption is often accompanied by the use of other legal or illegal psychotropic substances in an excessively noisy atmosphere.

In the absence of any social framework based on traditions, the group of young people is sociologically isolated in the collective invention of the party scene. Within this context, extreme behaviour may be a tactic leading to an amorous or sexual encounter. The freedom of these outings can also be paid for with the risk of boredom, of a social vacuum, which, itself, is associated with the desire and need for psychotropic substances.

Prevention must take into account what is really at stake behind this restructuring of the young contemporary party scene: comprehensive research into social sciences is needed here.

The advertising or health-related message is perceived and accepted much more readily when coming from a source that is appreciated by the recipient

In France, as regards alcohol and drinkers, advertisers are still nowadays reworking the clichés that, for the most part, were created under the July Monarchy, a period of generalisation of industrial alcohols. This imagery, forged by certain doctors specialising in hygiene, compare good and bad alcohol, good and bad drinkers, and good and bad alcohol consumption.

According to designers, good alcohol awakens the senses and stimulates the intelligence. It is a panacea and contributes to national wealth. The middle class who sample such beverages, discretely and from a connoisseur standpoint, do not allow themselves to be dominated by the drink, but dominate it themselves. At the other end of the spectrum, poor alcohol, which is consumed mainly by those from a more humble background—soldiers, the down-and-outs, peasants, and labourers in particular—hamper the senses and are poisons that give the people who drink it brutal, animal instincts and, finally, reify them.

In the 1840's, a few “humanists” contested these stereotypes that confused addiction and inebriation. But their comments, which were not welcome because they denounced chronic, middle class alcoholism, were not understood. The message was not taken up by physicians belonging to anti-alcohol leagues until the period between the two world wars.

Up until the mid-1950s, all the prevention posters were the same. The drinker, always portrayed as a man and a labourer, is a criminal devoid of human traits and engenders morons. Stories accentuate the harmful effects of alcohol on health.

Advertising in favour of alcohol obviously portrays the opposite: happy drinkers, stylishly dressed, often personified by the stars of politics, the cinema, or fashion. Slogans emphasise the “therapeutic” virtues of alcoholic beverages.

During the Glorious Thirties, the number of labourers decreased, and images of alcohol changed. At the same time, however, from this time onward, artists and doctors discovered the female drinker beneath the guise of the woman with a good job, who not only took over a man's role but also his “vices”, i.e., a woman who smoked and drank. Going beyond appearances, this upper class female drinker and the “young person” who replaced her in the late 1970s, present a number of similarities with the labourer drinker of the 19th century—they too drank spirits, which were consumed like psychotropic substances, in an attempt to quickly change the state of mind.

Prevention and promotion campaigns will adapt to these new images. In terms of health, designers are breaking tradition with hygiene-related strategies to reply, point by point, to alcohol consumers to overcome the false ideas portrayed by advertisements and to bring the consumer back to reality. In legends, the message stipulates that alcohol is not warming, is not a real food, does not boost strength, is not associated with life and health but with disease and death, it is not synonymous with freedom and evasion but with prison, and does not allow you to face up to situations but to lose face. Persons in charge of health campaigns, who from now on are addressing all social categories, no longer seek to portray the drinker as guilty but to make him/her responsible, to give him/her choices, such as “drink or drive”. They are no longer portrayed as “against”, i.e., against alcohol, against inebriation, or against the drinker's attitude but suggest an alternative to alcoholic drinks with advertisements “for” fruit juices and grape juice in particular.

Pro-alcohol advertising is also changing, not only to bring itself into line with the latest train of thought but also because it is about to be seriously regulated. The law of November 29th, 1960, which prevents alcohol from being associated with sport or driving and which does not allow the stimulating, aphrodisiac, or sedative properties of alcohol to be emphasised, conducted particularly sober advertising campaigns up to 1968 when alcohol advertising made its debut on the small screen. Despite the television media ban from 1975 onward, advertisers launched a major offensive to persuade their audience that alcohol promotes communication between people of different ages, gender, and social classes, that alcohol could be drunk without any hesitation in the workplace because it was a performance factor. After 1987, however, the messages changed. Alcohol is now only consumed between peer groups and people of the same age, at home and especially in the evening.

Table

Communication measures implemented by the Ministry for Health and the CFES in the form of audiovisual campaigns.

From 1990 onward, drinkers left the limelight as though advertisers were already prepared to adopt the restrictive measures that did not come into force until January 1991 (Évin law). Until 1995, artists were feeling their way, and advertisements were sober, unoriginal, and few in number. Finally, they succeeded in playing their game well while remaining within the strict framework imposed by the Évin law. They understand that the objective is less to show drinkers and alcohol as to create images and slogans that channel the recipient's thoughts via a slow, automated perception process, utilising all the graphic and photographic techniques available. At the present time, no country has surveys that can accurately determine the impact of these pro- or anti-alcohol images on their audience. Given the numerous variables involved, which are not only of an advertising but also of a commercial and sociocultural nature, it is difficult to establish a marked cause–effect relationship between advertising and alcohol consumption. Until now, research has been deployed in two complementary ways: experimental research and opinion polls that tend to establish correlations between individual exposure to advertising and consumption schedules.

Psychologists have tested the effects of pro-alcohol advertising on spectators chosen for their ability to express themselves and their diversity in terms of consumption. They showed them slides or advertisements promoting alcohol and observed their physical reactions during the broadcast and their “alcoholic” behaviour at the end of the presentation. Many epidemiologists have carried out two-pronged, selected surveys focusing mainly on young people and involving: exposure to a series of repeat press announcements followed by semi-directive interviews (or questionnaires) centred on memories of advertisements. Surveys on health campaigns are few and far between, hardly sophisticated, and all point to the same conclusions: daily drinkers levy even more criticism against these images than occasional drinkers.

These investigations raise several problems: the subjects are placed in a very difficult situation compared with that of an ordinary spectator who never sees 15 or 20 images of alcoholic drinks in succession. Furthermore, most experimental studies are carried out in a laboratory specialising in drug- or alcohol-related research.

Although several surveys have led to conflicting conclusions—some proving and others invalidating the effect of advertising on alcohol consumption—several results, on the other hand, are consistent, and certain recurring trends appear to be significant:

- Longitudinal studies prove that, firstly, young people are prejudiced against alcohol, but as they become adolescents, they change their opinion toward drinking. The reasons for this change in attitude cannot, however, be determined.

- It takes more than exposure to an advertisement to trigger an impact upon beliefs and behaviour. The audience must be aware of the fact that they are looking at an advertisement for a specific product and not simply at just any image. Children, unlike adults, generally think of advertisements as films.

- The advertising or health message is perceived and accepted more readily when it comes from a source that is appreciated by the spectator. The best-remembered advertisements appear to be those that star celebrities from the world of show business or sport. The health posters that are best received are those shown to young people by DJs or leading celebrities.

- The ads that are best remembered are those that employ attention-drawing techniques to their full capacity: slow motion and detailed images, extensive work on the soundtrack, particularly the reconfiguration of music and famous, patriotic songs, etc. Audiovisual advertising broadcast in a room or on the small screen, therefore, appears to have more impact than press announcements composed of fixed images and slogans.

A few isolated researchers have carried out textual analyses of press releases, slogans, and televised broadcasts. They have set themselves the task of understanding, through a detailed study of the composition of the image and possibly of the text, the characteristics of drinkers and the techniques used to influence the audience. They have set out not only to detect what is said and shown but also to establish the way in which the message is portrayed and the various graphical, linguistic, and pictorial experiments used in an attempt to grasp the audience's attention.

Studies that focus directly on pro-alcohol advertising highlight any trickery. Thus, in France, kept off-camera since the Évin law, the consumer-presence is implied rather than shown. In a large number of advertisements, the camera lens is installed instead of the public, in front of a table or a counter on which can be found glasses and a bottle photographed according to scale. With subtle lighting, the photographer succeeds in recreating the composition of the materials (the creamy foam, the sparkling bubbles, and a freshly misted glass, etc.); and there, you have it, an incentive to drink. An analysis of advertisements for alcohol-free drinks shows how designers convey messages of inebriation without displaying alcoholic drinks. Ever since the Évin law, alcohol manufacturers who often produce mineral waters, beers, and alcohol-free aperitifs as well, focus, in an advertisement for a soft drink, on venues traditionally associated with “drinking to excess”, namely bars and discotheques, and include doubles of famous singers (Edith Piaf) or actors (James Cagney, Humphrey Boggart) renowned for their overindulgence. They portray inebriated persons without alcohol, who stagger along, reel, and are the victims of hallucinations but who are intoxicated not with alcohol but with a risky sport.

Other researchers have analysed TV films and televised series watched mainly by young people. They portray drinkers as having two major traits: they are systematically personified by stars who made a positive social image at the end of their career and benefit from the highest social status in history.

At best, textual analysis has enabled researchers to discover the intentions, deliberate or otherwise, of advertisements. These investigations nevertheless have their uses in an area where designers do not necessarily confess their intentions.

Alcohol is involved three times more often in road-traffic accidents than in accidents in the workplace

Numerous studies have investigated the presence of alcohol in various types of accident to establish any correlation between blood alcohol levels and the accident.

Although alcohol is associated with various types of road-traffic accidents, it also plays a major role in domestic accidents, accidents at work, in fights and in drownings, etc. In 1992 in the United States, alcohol was found to be involved in 50% of the road-traffic accidents and in fewer than 20% of accidents occurring in the workplace.

In France, a multicentre study involving almost 5,000 accident victims admitted to 21 hospitals between October 1982 and March 1983 allowed the blood alcohol levels of the victims and two biological indicators, namely gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV), to be examined at the same time, confirming significant and chronic alcohol consumption. The results indicate that alcohol is very often involved in fights and road-traffic accidents: 60% of men involved in fights have a blood alcohol level exceeding 0.50 g/l. Sporting accidents and accidents in the workplace represent the lowest incidences of elevated blood alcohol levels (5% in men). In women, high blood alcohol levels are mainly evident in domestic accidents and fights.

Table

Alcohol-related accidents in the United States (according to Cherpitel, 1992).

Table

Alcohol-related accidents in France (report by the High Committee for the alcohol-related investigation and information, 1985).

According to this study, a high proportion of victims present with laboratory signs of significant and chronic alcohol consumption. This applies to 27% of men and 32% of women, taking all accident victims into account. Victims presenting with acute alcohol intake in the absence of any signs of chronicity are fewer in number and may be qualified as occasional drinkers (slightly over 10% in men and 2% in women). The average age is 32 years for men and 39 years for women. Among the accident victims presenting with signs of chronic alcohol intake, the average age is 41 years for men and 48 years for women. In cases of blood alcohol levels equal to or greater than 0.8 g/l, one-third reaches or exceeds 2 g/l in men and women less than 30 years of age. The size of the group of accident victims presenting with raised blood alcohol levels illustrates that the risk of accident is higher depending on blood alcohol levels. A more recent study in the United States (1996) involving over 3,000 patients in four emergency departments also shows the increase in various types of accident depending on alcohol consumption (quantity and frequency).

Table

Accidents according to alcohol consumption, based on an American study (according to Cherpitel, 1996).

Alcohol is responsible for approximately 1,900 deaths per year on the road

In France at the present time, alcohol is involved in one-third of fatal road-traffic accidents. The total number of people killed on the road in one year is around 5,700 (2003 update), and the number injured, 110,000. Alcohol is linked with around 1,900 deaths and 16,000 injuries on the road each year. In 1970, alcohol played a role in 40% of fatal accidents.

In France, 60% of the accidents where drivers have an illegal level of alcohol in the blood (>0.5 g/l) occur between midnight and 04.00. The number of alcohol-related cases in which women are responsible for fatal accidents is always 3 to 4 times less than that of men. However, the number of female drivers arrested for breaking the law and nighttime accidents involving one single vehicle is on the increase among women in Anglo-Saxon countries. Preventive actions should take into consideration the behavioural differences between men and women before driving.

The relative risk on the road for a given blood alcohol level decreases with age in both men and women. At equal blood alcohol levels, the risk of a road-traffic accident is higher for a young person than for an adult. Road-traffic accidents are a major cause of premature mortality in young people.

Experimental studies concerning the effects of alcohol on driving show that ability is adversely affected from a level of 0.2 g/l, generalising from 0.5 g/l for multiple functions: reduction in peripheral vision, in-depth vision, prolonged reaction time, poor judgement of distances and speed, difficulty to judge distance from parked vehicles and to follow mobile vehicles; impaired processing of information; alteration in immediate and differed visual memory; poor co-ordination of manoeuvres. Low doses of alcohol also have an effect on vigilance and attention especially for tasks that require the spatial processing of driving-related information, especially during periods of drowsiness in the afternoon or at night. Moreover, if cognitive function is disrupted, as is the case with heavy drinkers, then visual performance is also impaired.

Table

The increase in the relative risk (RR) of a fatal accident associated with an increase in the blood alcohol level of 0.2 g/l according to age and sex (according to Zador et al., 2000).

A link between the early onset of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related road-traffic accidents has been highlighted in certain longitudinal American studies. These studies show that people who started to drink before the legal age of consent (21 in the United States) present an additional risk of alcohol-related accident, regardless of the family history of alcohol dependence, frequency of consumption, and different variables associated with age and consumption.

Table

Evaluation of the "additional risk" of accident associated with the age of onset of consumption (according to Hingson, 2000).

Drivers of motor vehicles are not the only ones to be affected by the problem. The prevalence of alcohol consumption also has a significant impact on pedestrians, (motor) cyclists, and adult or children passengers. The significant mortality rate associated with the latter category is particularly due to the fact that passengers do not always wear a seat belt when the driver is under the influence of alcohol.

Table

Proportion of blood alcohol levels exceeding 0.8 g/l per category of users and per number of people involved (according to "Alcohol and accidents", High Committee for the investigation of and information on alcoholism, 1985).

In accidents where only one person is involved, motorcyclists are the group under the least influence of alcohol (there is, on average, a high proportion of young drivers who are more sober). On the other hand, in accidents involving several people, the differences are less marked with pedestrians being mostly under the influence of alcohol and cyclists to less of an extent.

Compared with our European neighbours, the SARTRE (Social attitudes related to traffic risk in Europe) surveys show that the French most often take to the wheel after consuming alcohol. Furthermore, alcohol intake by young French people is heading toward an Anglo-Saxon model (namely "binge drinking" or "celebratory" drinking on a Saturday night) with different alcohols and other psychotropic substances being combined more often, thus constituting one of the trigger factors in exacerbating accidental risk in young people.

One of the reasons accounting for the extent of road rage and mortality in our country lies in the historical delay in our culture with regard to implementing risk management and preventive strategies. The Scandinavians, who have one of the lowest road mortality rates in the world, realised, at a very early stage, those elements involved in road safety and implemented educational and preventive strategies. Norway was the first country in the world to adopt a maximum legal blood alcohol limit. In 1936, this was 0.5 g of alcohol per litre of blood (the current legal level in France, adopted in 1995), and the consequences of breaking the law were three weeks' imprisonment and a two-year driving ban. The School of Legal Philosophy in Uppsala, which recommended a tougher crackdown on offenders, stated that the law served an educational purpose: initially, drivers comply with the law due to the threat perceived or a fear of the police, then take this law on board, over time, so that it becomes a social and individual standard. Thus, the law no longer needs to be enforced as shown in current Norwegian data.

Globally, all the control-sanction models have been inspired by risk models of the Scandinavian type. These methods state that, in order to change drivers' behaviour, their perception of the risk—probability—of being checked or punished must be enhanced. This is the subjective risk. To do this, the risk of actually being checked must be accentuated. Therefore, the number of controls and punishments must be increased. This is the objective risk. All of these models seek to reduce the discrepancy between these two risks so that an objective risk can be internalised into a subjective risk aimed at modifying behaviour. The objective risk must be publicised at the same time. In Canada, it is the frequency of checks combined with moderate, yet repeated sanctions that supposedly reduces the incidence of law-breaking behaviour. In the United States, the influence of these two models would be applied alternately. In Australia, the controls should be carried out sufficiently often to trigger dissuasion by friends and family. As for the British, since the early 20th century, they have sought to involve drivers in decisions and apply control and sanctions. The American, Canadian, and Australian studies have demonstrated the preventive efficacy of lowering the legal blood alcohol limit for a few years in the case of newly qualified drivers.

Behaviour under the influence of alcohol is governed by complex, determining factors

Alcohol consumption prior to driving a vehicle is tantamount to taking a risk for which the psychological benefits are considered higher than the risks incurred. Thus, if alcohol is consumed by drivers then positive (euphoria and no inhibitions) and negative (arrests, accidents and conflicts, etc.) expectations conflict with each other. The risk may be badly perceived, if at all, if the blood alcohol level is estimated subjectively and in the presence of perceptive, cognitive and motor disruptions due to alcohol. Furthermore, the expectations of alcohol consumption differ between men and women, and according to the socio-cultural context. Passengers who have to travel in a vehicle whose driver is under the influence of alcohol perceive the risk. The latter is undertaken – it is not investigated voluntarily but simply accepted under the circumstances.

The preventive strategies applied to the problem of alcohol must, therefore, incorporate these various risk aspects: some should certainly focus on risk-taking by attempting to reinforce the positive aspects of alternatives to inebriation. Others may observe the risk perceived by emphasising the discrepancy between subjective estimates of alcohol consumption and the reality of the blood alcohol level. Other strategies may target peer group pressure, with individuals being forced to accept a risk that they do not really wish to take.

Behaviour while under the influence of alcohol, traditionally considered as a predicting factor for accidents, is now also considered as a sign of alcohol dependency. In fact, an illegal blood alcohol level very often suggests an alcohol-related problem as well. Every year, the 100,000 road convictions in France could, therefore, be considered as providing numerous opportunities for treatment. This opportunity is in the hands of the legal sector in particular. Driving while under the influence of alcohol is, in fact, one of the biggest offences dealt with by the legal profession (24% of all offences are road-related offences). Access to treatment via an incentive or a legal obligation seems to encourage patients to undertake a voluntary cure.

The discrepancy between positive blood alcohol levels and offences is offset by contraventions associated with a blood alcohol level ranging from 0.5 to 0.8 g/l, sentences covering offences and contraventions. In 94% of cases, the sentenced are males with an average age of 38 years. In 10 years, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds sentenced has fallen substantially from more than 20% to 13%, whereas the proportion of over 40-year-olds has increased by more than one-third, reaching 43% in 1999. Taking all these sentences into account, 10 % concern habitual offenders, the number of which is constantly increasing. The number of drivers sentenced for manslaughter committed under the influence of alcohol has been decreasing since the 1980s. Prison sentences were awarded in 98% of cases (half of which are partly closed or closed prisons). The number of sentences for involuntary wounding has also fallen since the 1990s. Prison sentences were given in 80% of these cases with closed imprisonment in less than 10% of cases.

Although preventive and repressive actions have been reinforced in France, the role of alcohol in fatal accidents and the “extreme risk” for young people has, nevertheless, scarcely changed. A differential approach to prevention is apparently needed in order to adapt the strategy to the type of offence. The law, by definition, applies to all drivers, but a single measure does not have the same effect on all. The group of offenders who commit crimes while under the influence of alcohol is not uniform. It comprises sub-groups with specific characteristics that therefore require appropriate, preventive treatment. Let's reconsider the principal factors involved:

- Age: Some approaches are effective for young people, but not for adults and vice-versa.

- Sex: The motivations underlying alcohol intake and offences appear to highlight differences between men and women.

- Anti-sociality: A fraction of the population of offenders has also been sentenced for offences and contraventions that do not involve road traffic. Once again, it seems obvious that a driver who occasionally consumes alcohol and who is well integrated socially cannot be dealt with in the same way as a driver with a criminal record who has already been charged with various offences.

- Psychopathology: A fraction of offenders present with related problems that compromise the efficacy of overly “light” approaches, such as awareness training periods to highlight certain aspects, and therefore benefit from an enhanced psychotherapeutic approach.

Alcohol could be responsible for 10% to 20% of accidents in the workplace

Although this is a recurring problem in the working environment, there have been no recent, precise studies of the implication of alcohol in accidents in the workplace. Some American studies reported in an international working review (Organisation internationale du travail (OIT); international working organisation) that alcohol and drugs trigger between 20% and 25% of accidents in the workplace and up to 30% of work-related deaths.

In France, according to the Association nationale de prévention de l'alcoolisme (Anpa, 2000–2001; national association for the prevention of alcoholism), alcohol is directly responsible for between 10% and 20% of accidents in the work place, taking all socioprofessional categories into account.

At the SNCF (French railway), alcohol is thought to be involved in 20% of the 13,500 work-related accidents that occur each year, although it has been noted that most of the accidents involved non-alcohol-dependent agents.

An extensive study including a systematic assay of blood alcohol levels in the workplace was carried out in France more than 40 years ago. The incidence of alcohol intake on the frequency of accidents in the workplace and the repetition thereof was evaluated in six companies involving over 3,000 controls and over 1,000 victims. According to the companies and sampling time, alcohol consumption exceeding 1 g/l affected between 1% and 5% of the control employees and 2.5% to 11.5% of the victims.

Two more recent studies carried out in the hospital emergency departments in Tours in 1982 and in Nancy in 1988 allowed the extent of alcohol consumption to be assessed in victims, regardless of the nature of the accident.

The Tours study focused on over 2,000 wounded admitted to emergency departments (road-traffic accidents, brawls, domestic or sport-related accidents, accidents at work, or travelling accidents). There were as many working or travelling accidents (to and from work) as road-traffic accidents (excluding travelling accidents). Alcohol blood levels were the lowest in victims of accidents in the workplace). In the case of the latter, 10.3% presented with a blood alcohol level exceeding 0.40 g/l, 1.2% had a blood alcohol level greater than 2 g/l, whereas 9.3% of the victims, taking all accidents into account, had a blood alcohol level greater than 2 g/l. In the study conducted at the CHRU, Nancy, almost 150 of the blood alcohol levels measured concerned victims injured in the workplace or on the way to work. The percentage of victims injured in the workplace with a detectable blood alcohol level below 0.80 g/l was 9.1%, and 2% presented with a blood alcohol level exceeding 2 g/l. The figures were higher for accidents on the way to work (3.6% and 14.3%, respectively).

Based on the 1983 study carried out by the High Committee for the investigation of and information on alcoholism, the influence of alcohol in the workplace would mainly involve accidents in which the victim would fall. In fact, based on this study, 14% of the victims sustaining a fall in the workplace had a blood alcohol level equal to or greater than 0.5 g/l.

Table

Distribution of blood alcohol levels in accidents sustained in the workplace1 in men and women (according to HCEIA, 1985).

As regards alcohol intake, company practice is not always applied

The problems of alcohol in the working environment have not been discussed for many years. In the last 10 years or so, however, the experiences encountered by employers' doctors with regard to this problem have been published in the literature.

Fifty years ago, alcohol consumption in the working environment was often associated with physically difficult working conditions (working in heat, dust, the difficulty of the task at hand, and the risk of poisoning, etc.), and alcohol was used as a means of hydration. Employers' doctors, at this particular time, set out to improve the conditions at work and, in doing so, to reduce the factors for alcohol consumption. Changes in working tools over these last 20 years have replaced the physical exertion of the job by a substantial increase in mental exertion associated with psychological problems and stress where alcohol consumption can “alleviate” these new difficulties.

A survey published in the United States in 1995 showed that men with stressful jobs were 27.5 times more likely to develop alcohol dependence if their jobs gave them no scope for decision-making but imposed marked, psychological pressure, and 3.4 times more likely to develop alcohol dependence in a job with no responsibility but warranting substantial physical effort. This survey did not reveal any risk of alcohol dependency for women carrying out the same type of work.

The employer's doctor must investigate the suitability of an employee for a given post. In this particular context, he/she must constantly examine the risk of alcohol consumption in the employee in relation to the risk inherent in the job (safety of the work) warranting vigilance and precision, or a certain rhythm (shift work or nights). The employer's doctor must also define optimum ergonomic conditions, be attentive to physiological and psychological rhythms depending on increasing difficulties associated with the demands for performance, profitability, and constant changes to current working tools, regardless of the professional context. One of these key issues, regardless of the risks of driving under the influence of alcohol, will also be to preserve the mental integrity of the employee by protecting his cognitive functions in particular, hence the importance of collective and individual preventive measures within the context of occupational medicine: informing all personnel of the risks associated with alcohol by calling on approved organisations, forming link groups within the company by involving various players (staff representatives, trade unions, CHSCT (committee for hygiene, safety and working conditions), human resources directorate and medico-social services, etc.). It is, in fact, essential to perpetuate these actions to ensure their long-term efficacy. Numerous experiments with media coverage in certain establishments help to modify the mentality (alcohol-free day, action taken in company restaurants, alcohol-free drinks, etc.) Some large companies have even drafted an alcohol charter defining regulations relating to alcohol consumption within the company (drafting of a charter on the prevention of alcohol-related risks at the CHU, Bordeaux, specifying the approach to adopt in various situations where a member of staff has a problem related with alcohol consumption).

It should be noted that the code of practice, even if outmoded, is often not applied when it comes to alcohol consumption. This legislation is old (partly dating back to 1913) and inappropriate ("No-one is allowed to bring into the company any alcohol beverages to be drunk by staff other than wine, beer, cider, perry and mead"). The internal regulation, when it exists, often fails to include prevention of the alcohol-related risk. Similarly, the problem of employee reinsertion or continuation of his/her professional activity is not considered. However, information relating to alcohol and its consequences is available increasingly often in the medical practice, with emphasis on national campaigns. The suggestion of a self-questionnaire, for example, can help to trigger debate on this subject in the working environment.

According to victims of violence, approximately 30% of the perpetrators had consumed alcohol

Studies carried out by the emergency departments in numerous countries show that victims of violence are more often under the influence of alcohol than those injured accidentally, with higher levels of consumption and more significant alcohol-related problems. In 1994, the emergency departments in the United States received 1,400,000 victims of personal violence (i.e., 0.6% of the total population), only one of the parties involved (perpetrator or victim) having drunk in 13% of cases according to the information provided by this population.

A Canadian survey of victimisation published in 1991 and completed in the late 1980s of a representative sample of adults in an average-sized Ontario town is interesting because it focuses on the entire life of the persons included in the survey. It relates violent events, and the persons questioned were either the victims or the witnesses. 51% of the perpetrators and 30% of the victims had drunk at the time of the events. Alcohol was present not only during legally repressed acts of violence but also in minor acts of daily aggression. There appears to be a continuum between daily violence and major violence. These facts apply to the population as a whole and not to a specific group: 60% of men and 40% of women admit to having been victims, threatened, or witnesses of violence, and 10% of men and women have been victims of violence. The men were often victims during their youth, whereas women relate more recent events. Alcohol-related incidents did not result in more injuries than aggressive behaviour when alcohol was not present. Conversely, the risk of injury increases with the victim's alcohol consumption. The latter varies according to the sex of the perpetrator of the violence and the victim. Alcohol is involved in 62% of conflicts between male protagonists, in 53% of cases where the victim is a woman and the perpetrator a man, and in 27% of cases where the aggressor is a woman.

Based on victimisation surveys carried out among United States residents over 12 years of age, there were an estimated 11.1 million victims of violence every year between 1992 and 1995. These victims of violence represent 4.4% of the overall population 4 (250 million inhabitants). Simple aggression also includes verbal threats. A quarter of the victims of violence were certain that the perpetrator had been drinking.

Slightly less than one-third of perpetrators of non-sexual aggression would have drunk alcohol, either alone or in conjunction with other products, the latter being few and far between (4% to 7%). The perpetrators of violent rapes consume fewer psychotropic substances than other aggressors. In the case of sexual aggression, alcohol, either alone or combined with other drugs, is involved in 37% of cases. This figure is increased to 41% if sexual aggression committed under the influence of other drugs is included.

Regardless of the relationships between the protagonists, the use of alcohol is more widespread than that of drugs. The prevalence of alcohol increases with the proximity between protagonists. Aggressors who attack their partner have consumed alcohol on two occasions of three, either alone or in conjunction with other psychoactive products.

Table

Prevalence of consumption by the aggressor according to links with the victim – according to 7.7 million victims who are certain of the reports they have given (according to Greenfeld, 1998).

Those who attack their family members have been drinking in one of two cases. Those people who attack a relation, a friend, or an unknown person have consumed alcohol in approximately one of three cases, either alone or in conjunction with other psychoactive products.

In France in 1969, a one-month study focusing on sentenced offences in which at least one of the protagonists had chronic or acute alcohol consumption revealed a high prevalence of alcohol in homicides and arson.

Table

Prevalence of chronic or acute alcohol intake by the parties involved (perpetrators or victims) for certain groups of offences in France (according to Bombet, 1970).

In 2000, a national victimisation survey involving a representative sample of 7,000 women between 20 and 59 years of age analysed the violence to which they had been subjected over the previous 12 months. One-third of these 7,000 women declared themselves to be victims of “domestic violence” (perpetrated by a partner) and, in most cases, involved insults, emotional blackmail, and psychological pressure (30% of victims); physical or sexual aggression accounted for 3.4% of cases of violence. At least one of the protagonists had been drinking in 36% of the violent cases experienced—only the man in 27% of cases and the woman in 5% of cases. In the remaining 4% of cases, both had been drinking. The perpetrator had been drinking in 31% of the most serious cases of physical aggression.

Alcohol consumption affects social status: quality of study, type of employment, employee level

Various authors are interested in the impact of alcohol on social status in terms of employee level, personal and family income, and the job itself, based on data collated during American national studies.

Generally speaking, a positive correlation between alcohol and the level of income was found up to daily consumption of one glass of alcohol. This correlation changed, however, beyond 5 glasses a day. Some studies show that, in households with an alcohol problem, the average income is cut by 31% compared with other households. The relationship between consumption and personal income varies in the studies according to the duration of dependency or abuse for both men and women. Alcohol abuse and dependency cut income by 1% in the case of subjects between 18 and 24 years of age (men or women) and by up to 10% for those between 55 and 64 years of age, the impact being greater for women than for men.

The impact of alcohol use on work is also analysed in empirical studies. The difference between full-time employment in non-alcoholics and alcoholics is significant for men between 30 and 44 years of age and between 45 and 59 (88% versus 73% in the younger group and 86% versus 68% in the older group). According to some studies, alcohol consumption is associated with significantly more absenteeism.

Some studies have investigated the impact of alcohol consumption during youth on study level. The authors note that the early symptoms of alcohol consumption during youth are associated with a reduction in study level. Frequent consumption among students is manifested by an average reduction of 2.3 years in higher education. As regards the impact of alcohol problems on the choice of a job, the authors note that excessive drinkers are more often “blue-collar workers”. In the “white-collar” professions, excessive drinkers earn 15% less than their non-alcoholic peers. The indirect effects of consumption and the problems associated with this consumption can therefore be just as significant as the direct effects. More targeted research in this domain should provide information on the extent and nature of the indirect effects that can impact upon the quality and level of studies, training, the choice of a partner and friends, the level and quality of experience in the working context, and other components of human significance.

In France according to the Gazel survey (20,000 GDF-EDF employees), the major consumers (five glasses per day and above) are found more frequently among production staff (17.3%) and those working outdoors. Their consumption did, however, fall between 1992 and 1998 (–1.8 glasses). Abstainers and the heavy drinkers are those with poorer career prospects. Single, divorced, and separated men and men living alone consume three times more alcohol than married or remarried men. Men who have a poor perception of their health, or who take medication to sleep, consume more. A follow-up of re-treated persons shows that the number of glasses consumed weekly increased one year after retirement in all retired people (production staff, foremen, and executives).

The cost of loss of income associated with illness or premature death costs four times more than health expenditure

Analysis of the economic consequences associated with excessive alcohol consumption is an area of vast, fertile research (most of these publications nevertheless originating from Anglo-Saxon countries). The diversity of the potential effects of alcoholism on the economy in fact implies studies that exceed the strict framework of assessing the repercussions of the disease on the health of individuals. In addition to the costs of the disease, expenditure attributed to alcohol-related criminal offences and road-traffic accidents is also taken account in similar research.

Evaluation of the cost of alcohol consumption is based on the use of aetiological ratios and the documentation of the costs of consequences, health or otherwise, linked with alcohol consumption. Traditionally, a distinction is made between direct medical costs (recourse to treatments) or non-medical costs (criminal offences and road-traffic accidents) and indirect costs (loss of potential income or production associated with morbidity and /or premature mortality).

Studies carried out abroad highlight the significant financial impact of alcohol on hospitals and institutions. The cost of alcoholism and its repercussions was thus estimated at 148 billion dollars in 1992, in the United States.

Table

The social cost of alcoholism in the United States in 1992, in millions of dollars (according to Harwood et coll., 1998) .

This study, supported by several others, emphasises the importance of indirect costs to the overall cost. 47% and 21%, respectively, of this cost, are, in fact represented by loss of income associated with illness or premature death. Conversely, health expenditure amounts to only 8.9% of the overall cost.

Another important question for the economist is that of knowing who bears the costs generated by alcoholism. This refers to the notion of “external costs”. These are costs that abusers make non-abusers pay for. According to the studies, external costs predominate, the person responsible for the excessive consumption of alcohol or his/her partner covering only 45% of the cost of alcoholism and its consequences.

In France, several studies have been devoted to investigating the cost of alcoholism. One of the studies estimates the direct medical costs of alcoholism at 2.4 billion Euros in 1996. Another study exceeds the restrictive framework of analysing care and also includes, in addition to loss of income and production, expenses incurred by criminal offences and road-traffic accidents as well as loss of mandatory samples due to excessive alcohol consumption. The overall amount of losses attributable to alcohol is thus estimated at 17.6 billion Euros. Health costs represent 15% of this total, thus far behind the loss of income and production (50%) and the expenses that road-traffic accidents incur for insurance companies (20%).