NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57.)

Trauma-informed care (TIC) involves a broad understanding of traumatic stress reactions and common responses to trauma. Providers need to understand how trauma can affect treatment presentation, engagement, and the outcome of behavioral health services. This chapter examines common experiences survivors may encounter immediately following or long after a traumatic experience.

Trauma, including one-time, multiple, or long-lasting repetitive events, affects everyone differently. Some individuals may clearly display criteria associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but many more individuals will exhibit resilient responses or brief subclinical symptoms or consequences that fall outside of diagnostic criteria. The impact of trauma can be subtle, insidious, or outright destructive. How an event affects an individual depends on many factors, including characteristics of the individual, the type and characteristics of the event(s), developmental processes, the meaning of the trauma, and sociocultural factors.

This chapter begins with an overview of common responses, emphasizing that traumatic stress reactions are normal reactions to abnormal circumstances. It highlights common short- and long-term responses to traumatic experiences in the context of individuals who may seek behavioral health services. This chapter discusses psychological symptoms not represented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013a), and responses associated with trauma that either fall below the threshold of mental disorders or reflect resilience. It also addresses common disorders associated with traumatic stress. This chapter explores the role of culture in defining mental illness, particularly PTSD, and ends by addressing co-occurring mental and substance-related disorders.

Sequence of Trauma Reactions

Survivors’ immediate reactions in the aftermath of trauma are quite complicated and are affected by their own experiences, the accessibility of natural supports and healers, their coping and life skills and those of immediate family, and the responses of the larger community in which they live. Although reactions range in severity, even the most acute responses are natural responses to manage trauma— they are not a sign of psychopathology. Coping styles vary from action oriented to reflective and from emotionally expressive to reticent. Clinically, a response style is less important than the degree to which coping efforts successfully allow one to continue necessary activities, regulate emotions, sustain self-esteem, and maintain and enjoy interpersonal contacts. Indeed, a past error in traumatic stress psychology, particularly regarding group or mass traumas, was the assumption that all survivors need to express emotions associated with trauma and talk about the trauma; more recent research indicates that survivors who choose not to process their trauma are just as psychologically healthy as those who do. The most recent psychological debriefing approaches emphasize respecting the individual’s style of coping and not valuing one type over another.

Foreshortened future: Trauma can affect one’s beliefs about the future via loss of hope, limited expectations about life, fear that life will end abruptly or early, or anticipation that normal life events won’t occur (e.g., access to education, ability to have a significant and committed relationship, good opportunities for work).

Initial reactions to trauma can include exhaustion, confusion, sadness, anxiety, agitation, numbness, dissociation, confusion, physical arousal, and blunted affect. Most responses are normal in that they affect most survivors and are socially acceptable, psychologically effective, and self-limited. Indicators of more severe responses include continuous distress without periods of relative calm or rest, severe dissociation symptoms, and intense intrusive recollections that continue despite a return to safety. Delayed responses to trauma can include persistent fatigue, sleep disorders, nightmares, fear of recurrence, anxiety focused on flashbacks, depression, and avoidance of emotions, sensations, or activities that are associated with the trauma, even remotely. Exhibit 1.3-1 outlines some common reactions.

Exhibit 1.3-1

Immediate and Delayed Reactions to Trauma.

Common Experiences and Responses to Trauma

A variety of reactions are often reported and/or observed after trauma. Most survivors exhibit immediate reactions, yet these typically resolve without severe long-term consequences. This is because most trauma survivors are highly resilient and develop appropriate coping strategies, including the use of social supports, to deal with the aftermath and effects of trauma. Most recover with time, show minimal distress, and function effectively across major life areas and developmental stages. Even so, clients who show little impairment may still have subclinical symptoms or symptoms that do not fit diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder (ASD) or PTSD. Only a small percentage of people with a history of trauma show impairment and symptoms that meet criteria for trauma-related stress disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders.

The following sections focus on some common reactions across domains (emotional, physical, cognitive, behavioral, social, and developmental) associated with singular, multiple, and enduring traumatic events. These reactions are often normal responses to trauma but can still be distressing to experience. Such responses are not signs of mental illness, nor do they indicate a mental disorder. Traumatic stress-related disorders comprise a specific constellation of symptoms and criteria.

Emotional

Emotional reactions to trauma can vary greatly and are significantly influenced by the individual’s sociocultural history. Beyond the initial emotional reactions during the event, those most likely to surface include anger, fear, sadness, and shame. However, individuals may encounter difficulty in identifying any of these feelings for various reasons. They might lack experience with or prior exposure to emotional expression in their family or community. They may associate strong feelings with the past trauma, thus believing that emotional expression is too dangerous or will lead to feeling out of control (e.g., a sense of “losing it” or going crazy). Still others might deny that they have any feelings associated with their traumatic experiences and define their reactions as numbness or lack of emotions.

Emotional dysregulation

Some trauma survivors have difficulty regulating emotions such as anger, anxiety, sadness, and shame—this is more so when the trauma occurred at a young age (van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, & Mandel, 1993). In individuals who are older and functioning well prior to the trauma, such emotional dysregulation is usually short lived and represents an immediate reaction to the trauma, rather than an ongoing pattern. Self-medication—namely, substance abuse—is one of the methods that traumatized people use in an attempt to regain emotional control, although ultimately it causes even further emotional dysregulation (e.g., substance-induced changes in affect during and after use). Other efforts toward emotional regulation can include engagement in high-risk or self-injurious behaviors, disordered eating, compulsive behaviors such as gambling or overworking, and repression or denial of emotions; however, not all behaviors associated with self-regulation are considered negative. In fact, some individuals find creative, healthy, and industrious ways to manage strong affect generated by trauma, such as through renewed commitment to physical activity or by creating an organization to support survivors of a particular trauma.

Traumatic stress tends to evoke two emotional extremes: feeling either too much (overwhelmed) or too little (numb) emotion. Treatment can help the client find the optimal level of emotion and assist him or her with appropriately experiencing and regulating difficult emotions. In treatment, the goal is to help clients learn to regulate their emotions without the use of substances or other unsafe behavior. This will likely require learning new coping skills and how to tolerate distressing emotions; some clients may benefit from mindfulness practices, cognitive restructuring, and trauma-specific desensitization approaches, such as exposure therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR; refer to Part 1, Chapter 6, for more information on trauma-specific therapies).

Numbing

Numbing is a biological process whereby emotions are detached from thoughts, behaviors, and memories. In the following case illustration, Sadhanna’s numbing is evidenced by her limited range of emotions associated with interpersonal interactions and her inability to associate any emotion with her history of abuse. She also possesses a belief in a foreshortened future. A prospective longitudinal study (Malta, Levitt, Martin, Davis, & Cloitre, 2009) that followed the development of PTSD in disaster workers highlighted the importance of understanding and appreciating numbing as a traumatic stress reaction. Because numbing symptoms hide what is going on inside emotionally, there can be a tendency for family members, counselors, and other behavioral health staff to assess levels of traumatic stress symptoms and the impact of trauma as less severe than they actually are.

Case Illustration: Sadhanna

Sadhanna is a 22-year-old woman mandated to outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment as the alternative to incarceration. She was arrested and charged with assault after arguing and fighting with another woman on the street. At intake, Sadhanna reported a 7-year history of alcohol abuse and one depressive episode at age 18. She was surprised that she got into a fight but admitted that she was drinking at the time of the incident. She also reported severe physical abuse at the hands of her mother’s boyfriend between ages 4 and 15. Of particular note to the intake worker was Sadhanna’s matter-of-fact way of presenting the abuse history. During the interview, she clearly indicated that she did not want to attend group therapy and hear other people talk about their feelings, saying, “I learned long ago not to wear emotions on my sleeve.”

Sadhanna reported dropping out of 10th grade, saying she never liked school. She didn’t expect much from life. In Sadhanna’s first weeks in treatment, she reported feeling disconnected from other group members and questioned the purpose of the group. When asked about her own history, she denied that she had any difficulties and did not understand why she was mandated to treatment. She further denied having feelings about her abuse and did not believe that it affected her life now. Group members often commented that she did not show much empathy and maintained a flat affect, even when group discussions were emotionally charged.

Physical

Diagnostic criteria for PTSD place considerable emphasis on psychological symptoms, but some people who have experienced traumatic stress may present initially with physical symptoms. Thus, primary care may be the first and only door through which these individuals seek assistance for trauma-related symptoms. Moreover, there is a significant connection between trauma, including adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and chronic health conditions. Common physical disorders and symptoms include somatic complaints; sleep disturbances; gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, neurological, musculoskeletal, respiratory, and dermatological disorders; urological problems; and substance use disorders.

Somatization

Somatization indicates a focus on bodily symptoms or dysfunctions to express emotional distress. Somatic symptoms are more likely to occur with individuals who have traumatic stress reactions, including PTSD. People from certain ethnic and cultural backgrounds may initially or solely present emotional distress via physical ailments or concerns. Many individuals who present with somatization are likely unaware of the connection between their emotions and the physical symptoms that they’re experiencing. At times, clients may remain resistant to exploring emotional content and remain focused on bodily complaints as a means of avoidance. Some clients may insist that their primary problems are physical even when medical evaluations and tests fail to confirm ailments. In these situations, somatization may be a sign of a mental illness. However, various cultures approach emotional distress through the physical realm or view emotional and physical symptoms and well-being as one. It is important not to assume that clients with physical complaints are using somatization as a means to express emotional pain; they may have specific conditions or disorders that require medical attention. Foremost, counselors need to refer for medical evaluation.

Advice to Counselors: Using Information About Biology and Trauma

- Educate your clients:

- –

Frame reexperiencing the event(s), hyperarousal, sleep disturbances, and other physical symptoms as physiological reactions to extreme stress.

- –

Communicate that treatment and other wellness activities can improve both psychological and physiological symptoms (e.g., therapy, meditation, exercise, yoga). You may need to refer certain clients to a psychiatrist who can evaluate them and, if warranted, prescribe psycho-tropic medication to address severe symptoms.

- –

Discuss traumatic stress symptoms and their physiological components.

- –

Explain links between traumatic stress symptoms and substance use disorders, if appropriate.

- –

Normalize trauma symptoms. For example, explain to clients that their symptoms are not a sign of weakness, a character flaw, being damaged, or going crazy.

- Support your clients and provide a message of hope—that they are not alone, they are not at fault, and recovery is possible and anticipated.

Biology of trauma

Trauma biology is an area of burgeoning research, with the promise of more complex and explanatory findings yet to come. Although a thorough presentation on the biological aspects of trauma is beyond the scope of this publication, what is currently known is that exposure to trauma leads to a cascade of biological changes and stress responses. These biological alterations are highly associated with PTSD, other mental illnesses, and substance use disorders. These include:

- Changes in limbic system functioning.

- Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity changes with variable cortisol levels.

- Neurotransmitter-related dysregulation of arousal and endogenous opioid systems.

As a clear example, early ACEs such as abuse, neglect, and other traumas affect brain development and increase a person’s vulnerability to encountering interpersonal violence as an adult and to developing chronic diseases and other physical illnesses, mental illnesses, substance-related disorders, and impairment in other life areas (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012).

Hyperarousal and sleep disturbances

A common symptom that arises from traumatic experiences is hyperarousal (also called hypervigilance). Hyperarousal is the body’s way of remaining prepared. It is characterized by sleep disturbances, muscle tension, and a lower threshold for startle responses and can persist years after trauma occurs. It is also one of the primary diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

Hyperarousal is a consequence of biological changes initiated by trauma. Although it serves as a means of self-protection after trauma, it can be detrimental. Hyperarousal can interfere with an individual’s ability to take the necessary time to assess and appropriately respond to specific input, such as loud noises or sudden movements. Sometimes, hyperarousal can produce overreactions to situations perceived as dangerous when, in fact, the circumstances are safe.

Case Illustration: Kimi

Kimi is a 35-year-old Native American woman who was group raped at the age of 16 on her walk home from a suburban high school. She recounts how her whole life changed on that day. “I never felt safe being alone after the rape. I used to enjoy walking everywhere. Afterward, I couldn’t tolerate the fear that would arise when I walked in the neighborhood. It didn’t matter whether I was alone or with friends—every sound that I heard would throw me into a state of fear. I felt like the same thing was going to happen again. It’s gotten better with time, but I often feel as if I’m sitting on a tree limb waiting for it to break. I have a hard time relaxing. I can easily get startled if a leaf blows across my path or if my children scream while playing in the yard. The best way I can describe how I experience life is by comparing it to watching a scary, suspenseful movie—anxiously waiting for something to happen, palms sweating, heart pounding, on the edge of your chair.”

Along with hyperarousal, sleep disturbances are very common in individuals who have experienced trauma. They can come in the form of early awakening, restless sleep, difficulty falling asleep, and nightmares. Sleep disturbances are most persistent among individuals who have trauma-related stress; the disturbances sometimes remain resistant to intervention long after other traumatic stress symptoms have been successfully treated. Numerous strategies are available beyond medication, including good sleep hygiene practices, cognitive rehearsals of nightmares, relaxation strategies, and nutrition.

Cognitive

Traumatic experiences can affect and alter cognitions. From the outset, trauma challenges the just-world or core life assumptions that help individuals navigate daily life (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). For example, it would be difficult to leave the house in the morning if you believed that the world was not safe, that all people are dangerous, or that life holds no promise. Belief that one’s efforts and intentions can protect oneself from bad things makes it less likely for an individual to perceive personal vulnerability. However, traumatic events—particularly if they are unexpected—can challenge such beliefs.

Cognitions and Trauma

The following examples reflect some of the types of cognitive or thought-process changes that can occur in response to traumatic stress.

Cognitive errors: Misinterpreting a current situation as dangerous because it resembles, even remotely, a previous trauma (e.g., a client overreacting to an overturned canoe in 8 inches of water, as if she and her paddle companion would drown, due to her previous experience of nearly drowning in a rip current 5 years earlier).

Excessive or inappropriate guilt: Attempting to make sense cognitively and gain control over a traumatic experience by assuming responsibility or possessing survivor’s guilt, because others who experienced the same trauma did not survive.

Idealization: Demonstrating inaccurate rationalizations, idealizations, or justifications of the perpetrator’s behavior, particularly if the perpetrator is or was a caregiver. Other similar reactions mirror idealization; traumatic bonding is an emotional attachment that develops (in part to secure survival) between perpetrators who engage in interpersonal trauma and their victims, and Stockholm syndrome involves compassion and loyalty toward hostage takers (de Fabrique, Van Hasselt, Vecchi, & Romano, 2007).

Trauma-induced hallucinations or delusions: Experiencing hallucinations and delusions that, although they are biological in origin, contain cognitions that are congruent with trauma content (e.g., a woman believes that a person stepping onto her bus is her father, who had sexually abused her repeatedly as child, because he wore shoes similar to those her father once wore).

Intrusive thoughts and memories: Experiencing, without warning or desire, thoughts and memories associated with the trauma. These intrusive thoughts and memories can easily trigger strong emotional and behavioral reactions, as if the trauma was recurring in the present. The intrusive thoughts and memories can come rapidly, referred to as flooding, and can be disruptive at the time of their occurrence. If an individual experiences a trigger, he or she may have an increase in intrusive thoughts and memories for a while. For instance, individuals who inadvertently are retraumatized due to program or clinical practices may have a surge of intrusive thoughts of past trauma, thus making it difficult for them to discern what is happening now versus what happened then. Whenever counseling focuses on trauma, it is likely that the client will experience some intrusive thoughts and memories. It is important to develop coping strategies before, as much as possible, and during the delivery of trauma-informed and trauma-specific treatment.

Let’s say you always considered your driving time as “your time”—and your car as a safe place to spend that time. Then someone hits you from behind at a highway entrance. Almost immediately, the accident affects how you perceive the world, and from that moment onward, for months following the crash, you feel unsafe in any car. You become hypervigilant about other drivers and perceive that other cars are drifting into your lane or failing to stop at a safe distance behind you. For a time, your perception of safety is eroded, often leading to compensating behaviors (e.g., excessive glancing into the rearview mirror to see whether the vehicles behind you are stopping) until the belief is restored or reworked. Some individuals never return to their previous belief systems after a trauma, nor do they find a way to rework them—thus leading to a worldview that life is unsafe. Still, many other individuals are able to return to organizing core beliefs that support their perception of safety.

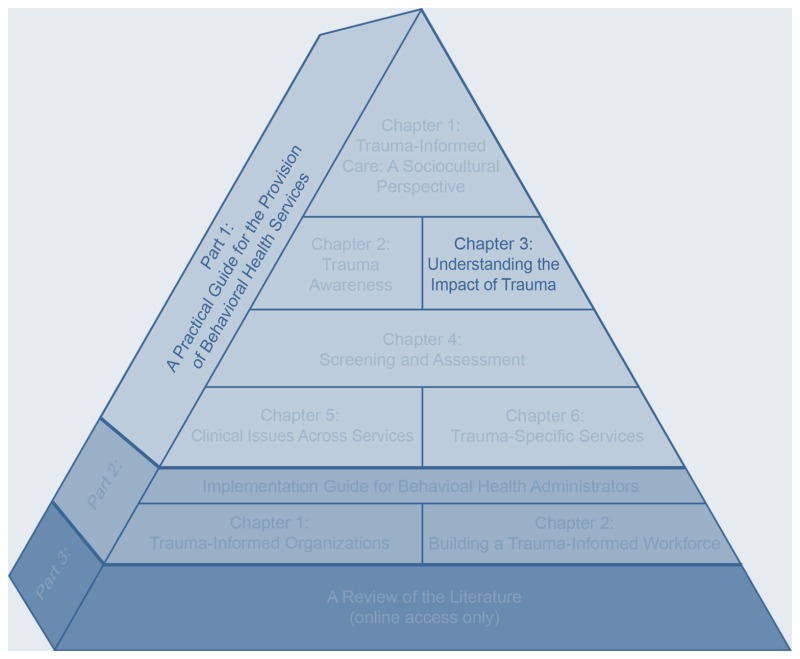

Many factors contribute to cognitive patterns prior to, during, and after a trauma. Adopting Beck and colleagues’ cognitive triad model (1979), trauma can alter three main cognitive patterns: thoughts about self, the world (others/environment), and the future. To clarify, trauma can lead individuals to see themselves as incompetent or damaged, to see others and the world as unsafe and unpredictable, and to see the future as hopeless—believing that personal suffering will continue, or negative outcomes will preside for the foreseeable future (see Exhibit 1.3-2). Subsequently, this set of cognitions can greatly influence clients’ belief in their ability to use internal resources and external support effectively. From a cognitive– behavioral perspective, these cognitions have a bidirectional relationship in sustaining or contributing to the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms after trauma. However, it is possible for cognitive patterns to help protect against debilitating psychological symptoms as well. Many factors contribute to cognitive patterns prior to, during, and after a trauma.

Exhibit 1.3-2

Cognitive Triad of Traumatic Stress.

Feeling different

An integral part of experiencing trauma is feeling different from others, whether or not the trauma was an individual or group experience. Traumatic experiences typically feel surreal and challenge the necessity and value of mundane activities of daily life. Survivors often believe that others will not fully understand their experiences, and they may think that sharing their feelings, thoughts, and reactions related to the trauma will fall short of expectations. However horrid the trauma may be, the experience of the trauma is typically profound.

The type of trauma can dictate how an individual feels different or believes that they are different from others. Traumas that generate shame will often lead survivors to feel more alienated from others—believing that they are “damaged goods.” When individuals believe that their experiences are unique and incomprehensible, they are more likely to seek support, if they seek support at all, only with others who have experienced a similar trauma.

Triggers and flashbacks

Triggers

A trigger is a stimulus that sets off a memory of a trauma or a specific portion of a traumatic experience. Imagine you were trapped briefly in a car after an accident. Then, several years later, you were unable to unlatch a lock after using a restroom stall; you might have begun to feel a surge of panic reminiscent of the accident, even though there were other avenues of escape from the stall. Some triggers can be identified and anticipated easily, but many are subtle and inconspicuous, often surprising the individual or catching him or her off guard. In treatment, it is important to help clients identify potential triggers, draw a connection between strong emotional reactions and triggers, and develop coping strategies to manage those moments when a trigger occurs. A trigger is any sensory reminder of the traumatic event: a noise, smell, temperature, other physical sensation, or visual scene. Triggers can generalize to any characteristic, no matter how remote, that resembles or represents a previous trauma, such as revisiting the location where the trauma occurred, being alone, having your children reach the same age that you were when you experienced the trauma, seeing the same breed of dog that bit you, or hearing loud voices. Triggers are often associated with the time of day, season, holiday, or anniversary of the event.

Flashbacks

A flashback is reexperiencing a previous traumatic experience as if it were actually happening in that moment. It includes reactions that often resemble the client’s reactions during the trauma. Flashback experiences are very brief and typically last only a few seconds, but the emotional aftereffects linger for hours or longer. Flashbacks are commonly initiated by a trigger, but not necessarily. Sometimes, they occur out of the blue. Other times, specific physical states increase a person’s vulnerability to reexperiencing a trauma, (e.g., fatigue, high stress levels). Flashbacks can feel like a brief movie scene that intrudes on the client. For example, hearing a car backfire on a hot, sunny day may be enough to cause a veteran to respond as if he or she were back on military patrol. Other ways people reexperience trauma, besides flashbacks, are via nightmares and intrusive thoughts of the trauma.

Advice to Counselors: Helping Clients Manage Flashbacks and Triggers

If a client is triggered in a session or during some aspect of treatment, help the client focus on what is happening in the here and now; that is, use grounding techniques. Behavioral health service providers should be prepared to help the client get regrounded so that they can distinguish between what is happening now versus what had happened in the past (see Covington, 2008, and Najavits, 2002b, 2007b, for more grounding techniques). Offer education about the experience of triggers and flashbacks, and then normalize these events as common traumatic stress reactions. Afterward, some clients need to discuss the experience and understand why the flashback or trigger occurred. It often helps for the client to draw a connection between the trigger and the traumatic event(s). This can be a preventive strategy whereby the client can anticipate that a given situation places him or her at higher risk for retraumatization and requires use of coping strategies, including seeking support.

Dissociation, depersonalization, and derealization

Dissociation is a mental process that severs connections among a person’s thoughts, memories, feelings, actions, and/or sense of identity. Most of us have experienced dissociation—losing the ability to recall or track a particular action (e.g., arriving at work but not remembering the last minutes of the drive). Dissociation happens because the person is engaged in an automatic activity and is not paying attention to his or her immediate environment. Dissociation can also occur during severe stress or trauma as a protective element whereby the individual incurs distortion of time, space, or identity. This is a common symptom in traumatic stress reactions.

Dissociation helps distance the experience from the individual. People who have experienced severe or developmental trauma may have learned to separate themselves from distress to survive. At times, dissociation can be very pervasive and symptomatic of a mental disorder, such as dissociative identity disorder (DID; formerly known as multiple personality disorder). According to the DSM-5, “dissociative disorders are characterized by a disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior” (APA, 2013a, p. 291). Dissociative disorder diagnoses are closely associated with histories of severe childhood trauma or pervasive, human-caused, intentional trauma, such as that experienced by concentration camp survivors or victims of ongoing political imprisonment, torture, or long-term isolation. A mental health professional, preferably with significant training in working with dissociative disorders and with trauma, should be consulted when a dissociative disorder diagnosis is suspected.

Potential Signs of Dissociation

- Fixed or “glazed” eyes

- Sudden flattening of affect

- Long periods of silence

- Monotonous voice

- Stereotyped movements

- Responses not congruent with the present context or situation

- Excessive intellectualization

The characteristics of DID can be commonly accepted experiences in other cultures, rather than being viewed as symptomatic of a traumatic experience. For example, in non-Western cultures, a sense of alternate beings within oneself may be interpreted as being inhabited by spirits or ancestors (Kirmayer, 1996). Other experiences associated with dissociation include depersonalization—psychologically “leaving one’s body,” as if watching oneself from a distance as an observer or through derealization, leading to a sense that what is taking place is unfamiliar or is not real.

If clients exhibit signs of dissociation, behavioral health service providers can use grounding techniques to help them reduce this defense strategy. One major long-term consequence of dissociation is the difficulty it causes in connecting strong emotional or physical reactions with an event. Often, individuals may believe that they are going crazy because they are not in touch with the nature of their reactions. By educating clients on the resilient qualities of dissociation while also emphasizing that it prevents them from addressing or validating the trauma, individuals can begin to understand the role of dissociation. All in all, it is important when working with trauma survivors that the intensity level is not so great that it triggers a dissociative reaction and prevents the person from engaging in the process.

Behavioral

Traumatic stress reactions vary widely; often, people engage in behaviors to manage the aftereffects, the intensity of emotions, or the distressing aspects of the traumatic experience. Some people reduce tension or stress through avoidant, self-medicating (e.g., alcohol abuse), compulsive (e.g., overeating), impulsive (e.g., high-risk behaviors), and/or self-injurious behaviors. Others may try to gain control over their experiences by being aggressive or subconsciously reenacting aspects of the trauma.

Behavioral reactions are also the consequences of, or learned from, traumatic experiences. For example, some people act like they can’t control their current environment, thus failing to take action or make decisions long after the trauma (learned helplessness). Other associate elements of the trauma with current activities, such as by reacting to an intimate moment in a significant relationship as dangerous or unsafe years after a date rape. The following sections discuss behavioral consequences of trauma and traumatic stress reactions.

Reenactments

A hallmark symptom of trauma is reexperiencing the trauma in various ways. Reexperiencing can occur through reenactments (literally, to “redo”), by which trauma survivors repetitively relive and recreate a past trauma in their present lives. This is very apparent in children, who play by mimicking what occurred during the trauma, such as by pretending to crash a toy airplane into a toy building after seeing televised images of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Attempts to understand reenactments are very complicated, as reenactments occur for a variety of reasons. Sometimes, individuals reenact past traumas to master them. Examples of reenactments include a variety of behaviors: self-injurious behaviors, hypersexuality, walking alone in unsafe areas or other high-risk behaviors, driving recklessly, or involvement in repetitive destructive relationships (e.g., repeatedly getting into romantic relationships with people who are abusive or violent), to name a few.

Self-harm and self-destructive behaviors

Self-harm is any type of intentionally self-inflicted harm, regardless of the severity of injury or whether suicide is intended. Often, self-harm is an attempt to cope with emotional or physical distress that seems overwhelming or to cope with a profound sense of dissociation or being trapped, helpless, and “damaged” (Herman, 1997; Santa Mina & Gallop, 1998). Self-harm is associated with past childhood sexual abuse and other forms of trauma as well as substance abuse. Thus, addressing self-harm requires attention to the client’s reasons for self-harm. More than likely, the client needs help recognizing and coping with emotional or physical distress in manageable amounts and ways.

Resilient Responses to Trauma

Many people find healthy ways to cope with, respond to, and heal from trauma. Often, people automatically reevaluate their values and redefine what is important after a trauma. Such resilient responses include:

- Increased bonding with family and community.

- Redefined or increased sense of purpose and meaning.

- Increased commitment to a personal mission.

- Revised priorities.

- Increased charitable giving and volunteerism.

Case Illustration: Marco

Marco, a 30-year-old man, sought treatment at a local mental health center after a 2-year bout of anxiety symptoms. He was an active member of his church for 12 years, but although he sought help from his pastor about a year ago, he reports that he has had no contact with his pastor or his church since that time. Approximately 3 years ago, his wife took her own life. He describes her as his soul-mate and has had a difficult time understanding her actions or how he could have prevented them.

In the initial intake, he mentioned that he was the first person to find his wife after the suicide and reported feelings of betrayal, hurt, anger, and devastation since her death. He claimed that everyone leaves him or dies. He also talked about his difficulty sleeping, having repetitive dreams of his wife, and avoiding relationships. In his first session with the counselor, he initially rejected the counselor before the counselor had an opportunity to begin reviewing and talking about the events and discomfort that led him to treatment.

In this scenario, Marco is likely reenacting his feelings of abandonment by attempting to reject others before he experiences another rejection or abandonment. In this situation, the counselor will need to recognize the reenactment, explore the behavior, and examine how reenactments appear in other situations in Marco’s life.

Among the self-harm behaviors reported in the literature are cutting, burning skin by heat (e.g., cigarettes) or caustic liquids, punching hard enough to self-bruise, head banging, hair pulling, self-poisoning, inserting foreign objects into bodily orifices, excessive nail biting, excessive scratching, bone breaking, gnawing at flesh, interfering with wound healing, tying off body parts to stop breathing or blood flow, swallowing sharp objects, and suicide. Cutting and burning are among the most common forms of self-harm.

Self-harm tends to occur most in people who have experienced repeated and/or early trauma (e.g., childhood sexual abuse) rather than in those who have undergone a single adult trauma (e.g., a community-wide disaster or a serious car accident). There are strong associations between eating disorders, self-harm, and substance abuse (Claes & Vandereycken, 2007; for discussion, see Harned, Najavits, & Weiss, 2006). Self-mutilation is also associated with (and part of the diagnostic criteria for) a number of personality disorders, including borderline and histrionic, as well as DID, depression, and some forms of schizophrenia; these disorders can co-occur with traumatic stress reactions and disorders.

It is important to distinguish self-harm that is suicidal from self-harm that is not suicidal and to assess and manage both of these very serious dangers carefully. Most people who engage in self-harm are not doing so with the intent to kill themselves (Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003)—although self-harm can be life threatening and can escalate into suicidality if not managed therapeutically. Self-harm can be a way of getting attention or manipulating others, but most often it is not. Self-destructive behaviors such as substance abuse, restrictive or binge eating, reckless automobile driving, or high-risk impulsive behavior are different from self-harming behaviors but are also seen in clients with a history of trauma. Self-destructive behaviors differ from self-harming behaviors in that there may be no immediate negative impact of the behavior on the individual; they differ from suicidal behavior in that there is no intent to cause death in the short term.

Advice to Counselors: Working With Clients Who Are Self-Injurious

Counselors who are unqualified or uncomfortable working with clients who demonstrate self-harming, self-destructive, or suicidal or homicidal ideation, intent, or behavior should work with their agencies and supervisors to refer such clients to other counselors. They should consider seeking specialized supervision on how to manage such clients effectively and safely and how to manage their feelings about these issues. The following suggestions assume that the counselor has had sufficient training and experience to work with clients who are self-injurious. To respond appropriately to a client who engages in self-harm, counselors should:

- Screen the client for self-harm and suicide risk at the initial evaluation and throughout treatment.

- Learn the client’s perspective on self-harm and how it “helps.”

- Understand that self-harm is often a coping strategy to manage the intensity of emotional and/or physical distress.

- Teach the client coping skills that improve his or her management of emotions without self-harm.

- Help the client obtain the level of care needed to manage genuine risk of suicide or severe self-injury. This might include hospitalization, more intensive programming (e.g., intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, residential treatment), or more frequent treatment sessions. The goal is to stabilize the client as quickly as possible, and then, if possible, begin to focus treatment on developing coping strategies to manage self-injurious and other harmful impulses.

- Consult with other team members, supervisors, and, if necessary, legal experts to determine whether one’s efforts with and conceptualization of the self-harming client fit best practice guidelines. See, for example, Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 42, Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Co-Occurring Disorders (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2005c). Document such consultations and the decisions made as a result of them thoroughly and frequently.

- Help the client identify how substance use affects self-harm. In some cases, it can increase the behavior (e.g., alcohol disinhibits the client, who is then more likely to self-harm). In other cases, it can decrease the behavior (e.g., heroin evokes relaxation and, thus, can lessen the urge to self-harm). In either case, continue to help the client understand how abstinence from substances is necessary so that he or she can learn more adaptive coping.

- Work collaboratively with the client to develop a plan to create a sense of safety. Individuals are affected by trauma in different ways; therefore, safety or a safe environment may mean something entirely different from one person to the next. Allow the client to define what safety means to him or her.

Counselors can also help the client prepare a safety card that the client can carry at all times. The card might include the counselor’s contact information, a 24-hour crisis number to call in emergencies, contact information for supportive individuals who can be contacted when needed, and, if appropriate, telephone numbers for emergency medical services. The counselor can discuss with the client the types of signs or crises that might warrant using the numbers on the card. Additionally, the counselor might check with the client from time to time to confirm that the information on the card is current.

TIP 50, Addressing Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT, 2009a), has examples of safety agreements specifically for suicidal clients and discusses their uses in more detail. There is no credible evidence that a safety agreement is effective in preventing a suicide attempt or death. Safety agreements for clients with suicidal thoughts and behaviors should only be used as an adjunct support accompanying professional screening, assessment, and treatment for people with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Keep in mind that safety plans or agreements may be perceived by the trauma survivor as a means of controlling behavior, subsequently replicating or triggering previous traumatic experiences.

All professionals—and in some States, anyone—could have ethical and legal responsibilities to those clients who pose an imminent danger to themselves or others. Clinicians should be aware of the pertinent State laws where they practice and the relevant Federal and professional regulations.

However, as with self-harming behavior, self-destructive behavior needs to be recognized and addressed and may persist—or worsen—without intervention.

Consumption of substances

Substance use often is initiated or increased after trauma. Clients in early recovery— especially those who develop PTSD or have it reactivated—have a higher relapse risk if they experience a trauma. In the first 2 months after September 11, 2001, more than a quarter of New Yorker residents who smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol, or used marijuana (about 265,000 people) increased their consumption. The increases continued 6 months after the attacks (Vlahov, Galea, Ahern, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2004). A study by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies, 2002) used National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to compare the first three quarters of 2001 with the last quarter and reported an increase in the prevalence rate for alcohol use among people 18 or older in the New York metropolitan area during the fourth quarter.

Interviews with New York City residents who were current or former cocaine or heroin users indicated that many who had been clean for 6 months or less relapsed after September 11, 2001. Others, who lost their income and could no longer support their habit, enrolled in methadone programs (Weiss et al., 2002). After the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, Oklahomans reported double the normal rate of alcohol use, smoking more cigarettes, and a higher incidence of initiating smoking months and even years after the bombing (Smith, Christiansen, Vincent, & Hann, 1999).

Self-medication

Khantzian’s self-medication theory (1985) suggests that drugs of abuse are selected for their specific effects. However, no definitive pattern has yet emerged of the use of particular substances in relation to PTSD or trauma symptoms. Use of substances can vary based on a variety of factors, including which trauma symptoms are most prominent for an individual and the individual’s access to particular substances. Unresolved traumas sometimes lurk behind the emotions that clients cannot allow themselves to experience. Substance use and abuse in trauma survivors can be a way to self-medicate and thereby avoid or displace difficult emotions associated with traumatic experiences. When the substances are withdrawn, the survivor may use other behaviors to self-soothe, self-medicate, or avoid emotions. As likely, emotions can appear after abstinence in the form of anxiety and depression.

Avoidance

Avoidance often coincides with anxiety and the promotion of anxiety symptoms. Individuals begin to avoid people, places, or situations to alleviate unpleasant emotions, memories, or circumstances. Initially, the avoidance works, but over time, anxiety increases and the perception that the situation is unbearable or dangerous increases as well, leading to a greater need to avoid. Avoidance can be adaptive, but it is also a behavioral pattern that reinforces perceived danger without testing its validity, and it typically leads to greater problems across major life areas (e.g., avoiding emotionally oriented conversations in an intimate relationship). For many individuals who have traumatic stress reactions, avoidance is commonplace. A person may drive 5 miles longer to avoid the road where he or she had an accident. Another individual may avoid crowded places in fear of an assault or to circumvent strong emotional memories about an earlier assault that took place in a crowded area. Avoidance can come in many forms. When people can’t tolerate strong affects associated with traumatic memories, they avoid, project, deny, or distort their trauma-related emotional and cognitive experiences. A key ingredient in trauma recovery is learning to manage triggers, memories, and emotions without avoidance—in essence, becoming desensitized to traumatic memories and associated symptoms.

Social/Interpersonal

A key ingredient in the early stage of TIC is to establish, confirm, or reestablish a support system, including culturally appropriate activities, as soon as possible. Social supports and relationships can be protective factors against traumatic stress. However, trauma typically affects relationships significantly, regardless of whether the trauma is interpersonal or is of some other type. Relationships require emotional exchanges, which means that others who have close relationships or friendships with the individual who survived the trauma(s) are often affected as well—either through secondary traumatization or by directly experiencing the survivor’s traumatic stress reactions. In natural disasters, social and community supports can be abruptly eroded and difficult to rebuild after the initial disaster relief efforts have waned.

Survivors may readily rely on family members, friends, or other social supports—or they may avoid support, either because they believe that no one will be understanding or trustworthy or because they perceive their own needs as a burden to others. Survivors who have strong emotional or physical reactions, including outbursts during nightmares, may pull away further in fear of being unable to predict their own reactions or to protect their own safety and that of others. Often, trauma survivors feel ashamed of their stress reactions, which further hampers their ability to use their support systems and resources adequately.

Many survivors of childhood abuse and interpersonal violence have experienced a significant sense of betrayal. They have often encountered trauma at the hands of trusted caregivers and family members or through significant relationships. This history of betrayal can disrupt forming or relying on supportive relationships in recovery, such as peer supports and counseling. Although this fear of trusting others is protective, it can lead to difficulty in connecting with others and greater vigilance in observing the behaviors of others, including behavioral health service providers. It is exceptionally difficult to override the feeling that someone is going to hurt you, take advantage of you, or, minimally, disappoint you. Early betrayal can affect one’s ability to develop attachments, yet the formation of supportive relationships is an important antidote in the recovery from traumatic stress.

Developmental

Each age group is vulnerable in unique ways to the stresses of a disaster, with children and the elderly at greatest risk. Young children may display generalized fear, nightmares, heightened arousal and confusion, and physical symptoms, (e.g., stomachaches, headaches). School-age children may exhibit symptoms such as aggressive behavior and anger, regression to behavior seen at younger ages, repetitious traumatic play, loss of ability to concentrate, and worse school performance. Adolescents may display depression and social withdrawal, rebellion, increased risky activities such as sexual acting out, wish for revenge and action-oriented responses to trauma, and sleep and eating disturbances (Hamblen, 2001). Adults may display sleep problems, increased agitation, hypervigilance, isolation or withdrawal, and increased use of alcohol or drugs. Older adults may exhibit increased withdrawal and isolation, reluctance to leave home, worsening of chronic illnesses, confusion, depression, and fear (DeWolfe & Nordboe, 2000b).

Neurobiological Development: Consequences of Early Childhood Trauma

Findings in developmental psychobiology suggest that the consequences of early maltreatment produce enduring negative effects on brain development (De Bellis, 2002; Liu, Diorio, Day, Francis, & Meaney, 2000; Teicher, 2002). Research suggests that the first stage in a cascade of events produced by early trauma and/or maltreatment involves the disruption of chemicals that function as neurotransmitters (e.g., cortisol, norepinephrine, dopamine), causing escalation of the stress response (Heim, Mletzko, Purselle, Musselman, & Nemeroff, 2008; Heim, Newport, Mletzko, Miller, & Nemeroff, 2008; Teicher, 2002). These chemical responses can then negatively affect critical neural growth during specific sensitive periods of childhood development and can even lead to cell death.

Adverse brain development can also result from elevated levels of cortisol and catecholamines by contributing to maturational failures in other brain regions, such as the prefrontal cortex (Meaney, Brake, & Gratton, 2002). Heim, Mletzko et al. (2008) found that the neuropeptide oxytocin— important for social affiliation and support, attachment, trust, and management of stress and anxiety—was markedly decreased in the cerebrospinal fluid of women who had been exposed to childhood maltreatment, particularly those who had experienced emotional abuse. The more childhood traumas a person had experienced, and the longer their duration, the lower that person’s current level of oxytocin was likely to be and the higher her rating of current anxiety was likely to be.

Using data from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study, an analysis by Anda, Felitti, Brown et al. (2006) confirmed that the risk of negative outcomes in affective, somatic, substance abuse, memory, sexual, and aggression-related domains increased as scores on a measure of eight ACEs increased. The researchers concluded that the association of study scores with these outcomes can serve as a theoretical parallel for the effects of cumulative exposure to stress on the developing brain and for the resulting impairment seen in multiple brain structures and functions.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (http://www.nctsn.org) offers information about childhood abuse, stress, and physiological responses of children who are traumatized. Materials are available for counselors, educators, parents, and caregivers. There are special sections on the needs of children in military families and on the impact of natural disasters on children’s mental health.

Subthreshold Trauma-Related Symptoms

Many trauma survivors experience symptoms that, although they do not meet the diagnostic criteria for ASD or PTSD, nonetheless limit their ability to function normally (e.g., regulate emotional states, maintain steady and rewarding social and family relationships, function competently at a job, maintain a steady pattern of abstinence in recovery). These symptoms can be transient, only arising in a specific context; intermittent, appearing for several weeks or months and then receding; or a part of the individual’s regular pattern of functioning (but not to the level of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria). Often, these patterns are termed “subthreshold” trauma symptoms. Like PTSD, the symptoms can be misdiagnosed as depression, anxiety, oran other mental illness. Likewise, clients who have experienced trauma may link some of their symptoms to their trauma and diagnose themselves as having PTSD, even though they do not meet all criteria for that disorder.

Combat Stress Reaction

A phenomenon unique to war, and one that counselors need to understand well, is combat stress reaction (CSR). CSR is an acute anxiety reaction occurring during or shortly after participating in military conflicts and wars as well as other operations within the war zone, known as the theater. CSR is not a formal diagnosis, nor is it included in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013a). It is similar to acute stress reaction, except that the precipitating event or events affect military personnel (and civilians exposed to the events) in an armed conflict situation. The terms “combat stress reaction” and “posttraumatic stress injury” are relatively new, and the intent of using these new terms is to call attention to the unique experiences of combat-related stress as well as to decrease the shame that can be associated with seeking behavioral health services for PTSD (for more information on veterans and combat stress reactions, see the planned TIP, Reintegration-Related Behavioral Health Issues for Veterans and Military Families; SAMHSA, planned f).

Case Illustration: Frank

Frank is a 36-year-old man who was severely beaten in a fight outside a bar. He had multiple injuries, including broken bones, a concussion, and a stab wound in his lower abdomen. He was hospitalized for 3.5 weeks and was unable to return to work, thus losing his job as a warehouse forklift operator. For several years, when faced with situations in which he perceived himself as helpless and overwhelmed, Frank reacted with violent anger that, to others, appeared grossly out of proportion to the situation. He has not had a drink in almost 3 years, but the bouts of anger persist and occur three to five times a year. They leave Frank feeling even more isolated from others and alienated from those who love him. He reports that he cannot watch certain television shows that depict violent anger; he has to stop watching when such scenes occur. He sometimes daydreams about getting revenge on the people who assaulted him.

Psychiatric and neurological evaluations do not reveal a cause for Frank’s anger attacks. Other than these symptoms, Frank has progressed well in his abstinence from alcohol. He attends a support group regularly, has acquired friends who are also abstinent, and has reconciled with his family of origin. His marriage is more stable, although the episodes of rage limit his wife’s willingness to commit fully to the relationship. In recounting the traumatic event in counseling, Frank acknowledges that he thought he was going to die as a result of the fight, especially when he realized he had been stabbed. As he described his experience, he began to become very anxious, and the counselor observed the rage beginning to appear.

After his initial evaluation, Frank was referred to an outpatient program that provided trauma-specific interventions to address his subthreshold trauma symptoms. With a combination of cognitive– behavioral counseling, EMDR, and anger management techniques, he saw a gradual decrease in symptoms when he recalled the assault. He started having more control of his anger when memories of the trauma emerged. Today, when feeling trapped, helpless, or overwhelmed, Frank has resources for coping and does not allow his anger to interfere with his marriage or other relationships.

Although stress mobilizes an individual’s physical and psychological resources to perform more effectively in combat, reactions to the stress may persist long after the actual danger has ended. As with other traumas, the nature of the event(s), the reactions of others, and the survivor’s psychological history and resources affect the likelihood and severity of CSR. With combat veterans, this translates to the number, intensity, and duration of threat factors; the social support of peers in the veterans’ unit; the emotional and cognitive resilience of the service members; and the quality of military leadership. CSR can vary from manageable and mild to debilitating and severe. Common, less severe symptoms of CSR include tension, hypervigilance, sleep problems, anger, and difficulty concentrating. If left untreated, CSR can lead to PTSD.

Common causes of CSR are events such as a direct attack from insurgent small arms fire or a military convoy being hit by an improvised explosive device, but combat stressors encompass a diverse array of traumatizing events, such as seeing grave injuries, watching others die, and making on-the-spot decisions in ambiguous conditions (e.g., having to determine whether a vehicle speeding toward a military checkpoint contains insurgents with explosives or a family traveling to another area). Such circumstances can lead to combat stress. Military personnel also serve in noncombat positions (e.g., healthcare and administrative roles), and personnel filling these supportive roles can be exposed to combat situations by proximity or by witnessing their results.

Advice to Counselors: Understanding the Nature of Combat Stress

Several sources of information are available to help counselors deepen their understanding of combat stress and postdeployment adjustment. Friedman (2006) explains how a prolonged combat-ready stance, which is adaptive in a war zone, becomes hypervigilance and overprotectiveness at home. He makes the point that the “mutual interdependence, trust, and affection” (p. 587) that are so necessarily a part of a combat unit are different from relationships with family members and colleagues in a civilian workplace. This complicates the transition to civilian life. Wheels Down: Adjusting to Life After Deployment (Moore & Kennedy, 2011) provides practical advice for military service members, including inactive or active duty personnel and veterans, in transitioning from the theater to home.

The following are just a few of the many resources and reports focused on combat-related psychological and stress issues:

- Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008)

- On Killing (Grossman, 1995), an indepth analysis of the psychological dynamics of combat

- Haunted by Combat (Paulson & Krippner, 2007), which contains specific chapters on Reserve and National Guard troops and female veterans

- Treating Young Veterans: Promoting Resilience Through Practice and Advocacy (Kelly, Howe-Barksdale, & Gitelson, 2011)

Specific Trauma-Related Psychological Disorders

Part of the definition of trauma is that the individual responds with intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Beyond that, in both the short term and the long term, trauma comprises a range of reactions from normal (e.g., being unable to concentrate, feeling sad, having trouble sleeping) to warranting a diagnosis of a trauma-related mental disorder. Most people who experience trauma have no long-lasting disabling effects; their coping skills and the support of those around them are sufficient to help them overcome their difficulties, and their ability to function on a daily basis over time is unimpaired. For others, though, the symptoms of trauma are more severe and last longer. The most common diagnoses associated with trauma are PTSD and ASD, but trauma is also associated with the onset of other mental disorders—particularly substance use disorders, mood disorders, various anxiety disorders, and personality disorders. Trauma also typically exacerbates symptoms of preexisting disorders, and, for people who are predisposed to a mental disorder, trauma can precipitate its onset. Mental disorders can occur almost simultaneously with trauma exposure or manifest sometime thereafter.

Acute Stress Disorder

ASD represents a normal response to stress. Symptoms develop within 4 weeks of the trauma and can cause significant levels of distress. Most individuals who have acute stress reactions never develop further impairment or PTSD. Acute stress disorder is highly associated with the experience of one specific trauma rather than the experience of long-term exposure to chronic traumatic stress. Diagnostic criteria are presented in Exhibit 1.3-3.

Exhibit 1.3-3

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for ASD. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation in one (or more) of the following ways: Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s).

The primary presentation of an individual with an acute stress reaction is often that of someone who appears overwhelmed by the traumatic experience. The need to talk about the experience can lead the client to seem self-centered and unconcerned about the needs of others. He or she may need to describe, in repetitive detail, what happened, or may seem obsessed with trying to understand what happened in an effort to make sense of the experience. The client is often hypervigilant and avoids circumstances that are reminders of the trauma. For instance, someone who was in a serious car crash in heavy traffic can become anxious and avoid riding in a car or driving in traffic for a finite time afterward. Partial amnesia for the trauma often accompanies ASD, and the individual may repetitively question others to fill in details. People with ASD symptoms sometimes seek assurance from others that the event happened in the way they remember, that they are not “going crazy” or “losing it,” and that they could not have prevented the event. The next case illustration demonstrates the time-limited nature of ASD.

Differences between ASD and PTSD

It is important to consider the differences between ASD and PTSD when forming a diagnostic impression. The primary difference is the amount of time the symptoms have been present. ASD resolves 2 days to 4 weeks after an event, whereas PTSD continues beyond the 4-week period. The diagnosis of ASD can change to a diagnosis of PTSD if the condition is noted within the first 4 weeks after the event, but the symptoms persist past 4 weeks.

ASD also differs from PTSD in that the ASD diagnosis requires 9 out of 14 symptoms from five categories, including intrusion, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance, and arousal. These symptoms can occur at the time of the trauma or in the following month. Studies indicate that dissociation at the time of trauma is a good predictor of subsequent PTSD, so the inclusion of dissociative symptoms makes it more likely that those who develop ASD will later be diagnosed with PTSD (Bryant & Harvey, 2000). Additionally, ASD is a transient disorder, meaning that it is present in a person’s life for a relatively short time and then passes. In contrast, PTSD typically becomes a primary feature of an individual’s life. Over a lengthy period, PTSD can have profound effects on clients’ perceptions of safety, their sense of hope for the future, their relationships with others, their physical health, the appearance of psychiatric symptoms, and their patterns of substance use and abuse.

There are common symptoms between PTSD and ASD, and untreated ASD is a possible predisposing factor to PTSD, but it is unknown whether most people with ASD are likely to develop PTSD. There is some suggestion that, as with PTSD, ASD is more prevalent in women than in men (Bryant & Harvey, 2003). However, many people with PTSD do not have a diagnosis or recall a history of acute stress symptoms before seeking treatment for or receiving a diagnosis of PTSD.

Case Illustration: Sheila

Two months ago, Sheila, a 55-year-old married woman, experienced a tornado in her home town. In the previous year, she had addressed a long-time marijuana use problem with the help of a treatment program and had been abstinent for about 6 months. Sheila was proud of her abstinence; it was something she wanted to continue. She regarded it as a mark of personal maturity; it improved her relationship with her husband, and their business had flourished as a result of her abstinence.

During the tornado, an employee reported that Sheila had become very agitated and had grabbed her assistant to drag him under a large table for cover. Sheila repeatedly yelled to her assistant that they were going to die. Following the storm, Sheila could not remember certain details of her behavior during the event. Furthermore, Sheila said that after the storm, she felt numb, as if she was floating out of her body and could watch herself from the outside. She stated that nothing felt real and it was all like a dream.

Following the tornado, Sheila experienced emotional numbness and detachment, even from people close to her, for about 2 weeks. The symptoms slowly decreased in intensity but still disrupted her life. Sheila reported experiencing disjointed or unconnected images and dreams of the storm that made no real sense to her. She was unwilling to return to the building where she had been during the storm, despite having maintained a business at this location for 15 years. In addition, she began smoking marijuana again because it helped her sleep. She had been very irritable and had uncharacteristic angry outbursts toward her husband, children, and other family members.

As a result of her earlier contact with a treatment program, Sheila returned to that program and engaged in psychoeducational, supportive counseling focused on her acute stress reaction. She regained abstinence from marijuana and returned shortly to a normal level of functioning. Her symptoms slowly diminished over a period of 3 weeks. With the help of her counselor, she came to understand the link between the trauma and her relapse, regained support from her spouse, and again felt in control of her life.

Effective interventions for ASD can significantly reduce the possibility of the subsequent development of PTSD. Effective treatment of ASD can also reduce the incidence of other co-occurring problems, such as depression, anxiety, dissociative disorders, and compulsive behaviors (Bryant & Harvey, 2000). Intervention for ASD also helps the individual develop coping skills that can effectively prevent the recurrence of ASD after later traumas.

Although predictive science for ASD and PTSD will continue to evolve, both disorders are associated with increased substance use and mental disorders and increased risk of relapse; therefore, effective screening for ASD and PTSD is important for all clients with these disorders. Individuals in early recovery—lacking well-practiced coping skills, lacking environmental supports, and already operating at high levels of anxiety—are particularly susceptible to ASD. Events that would not normally be disabling can produce symptoms of intense helplessness and fear, numbing and depersonalization, disabling anxiety, and an inability to handle normal life events. Counselors should be able to recognize ASD and treat it rather than attributing the symptoms to a client’s lack of motivation to change, being “dry drunk” (for those in substance abuse recovery), or being manipulative.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

The trauma-related disorder that receives the greatest attention is PTSD; it is the most commonly diagnosed trauma-related disorder, and its symptoms can be quite debilitating over time. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that PTSD symptoms are represented in a number of other mental illnesses, including major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders, and psychotic disorders (Foa et al., 2006). The DSM-5 (APA, 2013a) identifies four symptom clusters for PTSD: presence of intrusion symptoms, persistent avoidance of stimuli, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and marked alterations in arousal and reactivity. Individuals must have been exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the symptoms must produce significant distress and impairment for more than 4 weeks (Exhibit 1.3-4).

Exhibit 1.3-4

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD. Note: The following criteria apply to adults, adolescents, and children older than 6 years. For children 6 years and younger, see the DSM-5 section titled “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder for Children 6 Years (more...)

Case Illustration: Michael

Michael is a 62-year-old Vietnam veteran. He is a divorced father of two children and has four grandchildren. Both of his parents were dependent on alcohol. He describes his childhood as isolated. His father physically and psychologically abused him (e.g., he was beaten with a switch until he had welts on his legs, back, and buttocks). By age 10, his parents regarded him as incorrigible and sent him to a reformatory school for 6 months. By age 15, he was using marijuana, hallucinogens, and alcohol and was frequently truant from school.

At age 19, Michael was drafted and sent to Vietnam, where he witnessed the deaths of six American military personnel. In one incident, the soldier he was next to in a bunker was shot. Michael felt helpless as he talked to this soldier, who was still conscious. In Vietnam, Michael increased his use of both alcohol and marijuana. On his return to the United States, Michael continued to drink and use marijuana. He reenlisted in the military for another tour of duty.

His life stabilized in his early 30s, as he had a steady job, supportive friends, and a relatively stable family life. However, he divorced in his late 30s. Shortly thereafter, he married a second time, but that marriage ended in divorce as well. He was chronically anxious and depressed and had insomnia and frequent nightmares. He periodically binged on alcohol. He complained of feeling empty, had suicidal ideation, and frequently stated that he lacked purpose in his life.

In the 1980s, Michael received several years of mental health treatment for dysthymia. He was hospitalized twice and received 1 year of outpatient psychotherapy. In the mid-1990s, he returned to outpatient treatment for similar symptoms and was diagnosed with PTSD and dysthymia. He no longer used marijuana and rarely drank. He reported that he didn’t like how alcohol or other substances made him feel anymore—he felt out of control with his emotions when he used them. Michael reported symptoms of hyperarousal, intrusion (intrusive memories, nightmares, and preoccupying thoughts about Vietnam), and avoidance (isolating himself from others and feeling “numb”). He reported that these symptoms seemed to relate to his childhood abuse and his experiences in Vietnam. In treatment, he expressed relief that he now understood the connection between his symptoms and his history.

Certain characteristics make people more susceptible to PTSD, including one’s unique personal vulnerabilities at the time of the traumatic exposure, the support (or lack of support) received from others at the time of the trauma and at the onset of trauma-related symptoms, and the way others in the person’s environment gauge the nature of the traumatic event (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000).

People with PTSD often present varying clinical profiles and histories. They can experience symptoms that are activated by environmental triggers and then recede for a period of time. Some people with PTSD who show mostly psychiatric symptoms (particularly depression and anxiety) are misdiagnosed and go untreated for their primary condition. For many people, the trauma experience and diagnosis are obscured by co-occurring substance use disorder symptoms. The important feature of PTSD is that the disorder becomes an orienting feature of the individual’s life. How well the person can work, with whom he or she associates, the nature of close and intimate relationships, the ability to have fun and rejuvenate, and the way in which an individual goes about confronting and solving problems in life are all affected by the client’s trauma experiences and his or her struggle to recover.

Posttraumatic stress disorder: Timing of symptoms

Although symptoms of PTSD usually begin within 3 months of a trauma in adulthood, there can be a delay of months or even years before symptoms appear for some people. Some people may have minimal symptoms after a trauma but then experience a crisis later in life. Trauma symptoms can appear suddenly, even without conscious memory of the original trauma or without any overt provocation. Survivors of abuse in childhood can have a delayed response triggered by something that happens to them as adults. For example, seeing a movie about child abuse can trigger symptoms related to the trauma. Other triggers include returning to the scene of the trauma, being reminded of it in some other way, or noting the anniversary of an event. Likewise, combat veterans and survivors of community-wide disasters may seem to be coping well shortly after a trauma, only to have symptoms emerge later when their life situations seem to have stabilized. Some clients in substance abuse recovery only begin to experience trauma symptoms when they maintain abstinence for some time. As individuals decrease tension-reducing or self-medicating behaviors, trauma memories and symptoms can emerge.

Advice to Counselors: Helping Clients With Delayed Trauma Responses

Clients who are experiencing a delayed trauma response can benefit if you help them to:

- Create an environment that allows acknowledgment of the traumatic event(s).

- Discuss their initial recall or first suspicion that they were having a traumatic response.

- Become educated on delayed trauma responses.

- Draw a connection between the trauma and presenting trauma-related symptoms.

- Create a safe environment.

- Explore their support systems and fortify them as needed.

- Understand that triggers can precede traumatic stress reactions, including delayed responses to trauma.

- Identify their triggers.

- Develop coping strategies to navigate and manage symptoms.

Culture and posttraumatic stress

Although research is limited across cultures, PTSD has been observed in Southeast Asian, South American, Middle Eastern, and Native American survivors (Osterman & de Jong, 2007; Wilson & Tang, 2007). As Stamm and Friedman (2000) point out, however, simply observing PTSD does not mean that it is the “best conceptual tool for characterizing post-traumatic distress among non-Western individuals” (p. 73). In fact, many trauma-related symptoms from other cultures do not fit the DSM-5 criteria. These include somatic and psychological symptoms and beliefs about the origins and nature of traumatic events. Moreover, religious and spiritual beliefs can affect how a survivor experiences a traumatic event and whether he or she reports the distress. For example, in societies where attitudes toward karma and the glorification of war veterans are predominant, it is harder for war veterans to come forward and disclose that they are emotionally overwhelmed or struggling. It would be perceived as inappropriate and possibly demoralizing to focus on the emotional distress that he or she still bears. (For a review of cultural competence in treating trauma, refer to Brown, 2008.)

Methods for measuring PTSD are also culturally specific. As part of a project begun in 1972, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) embarked on a joint study to test the cross-cultural applicability of classification systems for various diagnoses. WHO and NIH identified apparently universal factors of psychological disorders and developed specific instruments to measure them. These instruments, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview and the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, include certain criteria from the DSM (Fourth Edition, Text Revision; APA, 2000a) as well as criteria from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10; Exhibit 1.3-5).

Exhibit 1.3-5

ICD-10 Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD. The patient must have been exposed to a stressful event or situation (either brief or long-lasting) of exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature, which would be likely to cause pervasive distress in almost anyone. (more...)

Complex trauma and complex traumatic stress

When individuals experience multiple traumas, prolonged and repeated trauma during childhood, or repetitive trauma in the context of significant interpersonal relationships, their reactions to trauma have unique characteristics (Herman, 1992). This unique constellation of reactions, called complex traumatic stress, is not recognized diagnostically in the DSM-5, but theoretical discussions and research have begun to highlight the similarities and differences in symptoms of posttraumatic stress versus complex traumatic stress (Courtois & Ford, 2009). Often, the symptoms generated from complex trauma do not fully match PTSD criteria and exceed the severity of PTSD. Overall, literature reflects that PTSD criteria or subthreshold symptoms do not fully account for the persistent and more impairing clinical presentation of complex trauma. Even though current research in the study of traumatology is prolific, it is still in the early stages of development. The idea that there may be more diagnostic variations or subtypes is forthcoming, and this will likely pave the way for more client-matching interventions to better serve those individuals who have been repeatedly exposed to multiple, early childhood, and/or interpersonal traumas.

Other Trauma-Related and Co-Occurring Disorders