NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Office on Smoking and Health (US). Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2001 Mar.

Table of Contents

- Level of Parental Supervision, Involvement, or Attachment

- References

Introduction

The published work on smoking initiation, maintenance, and cessation, together with descriptive examinations of the trends and themes of cigarette marketing, has provided insights into why women start to smoke and why they continue. Numerous scholars (e.g., Magnusson 1981; Bandura 1986; Sadava 1987; Frankenhaeuser 1991; Jessor et al. 1991; DeKay and Buss 1992) have argued that a thorough understanding of any behavior must be based on a comprehensive analysis of the broad social environment or cultural milieu surrounding the behavior, the immediate social situation or context in which the behavior occurs, the characteristics or disposition of the person performing the behavior, the behavior itself and closely related behaviors, and the interaction of all these conditions. Research on the social, cultural, and personal factors that influence women's smoking has been based on the social and psychological theory of the past several decades, and this research has burgeoned in recent years. Because smoking initiation among, maintenance and cessation among, and tobacco marketing to women have been studied by investigators using a variety of disciplinary perspectives and approaches, no single organizing framework exists for addressing the question of why women smoke. The research has shown that like most behaviors, tobacco use or nonuse results from a complex mix of influences that range from factors that are directly tied to tobacco use (e.g., beliefs about the consequences of smoking) to those that appear to have little to do with tobacco use (e.g., parenting styles and school characteristics).

Factors Influencing Initiation of Smoking

Overview of Studies Examined

Nearly all first use of tobacco occurs before high school graduation, and because nicotine is addictive, adolescents who smoke regularly are likely to become adult smokers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] 1994). Research on smoking initiation has, therefore, focused on adolescents and has been informed by a wealth of behavioral studies. Predictors of use of tobacco and other substances (Conrad et al. 1992; Hawkins et al. 1992; USDHHS 1994) and theories of adolescents' use of such substances (Petraitis et al. 1995) point to a complex set of interrelated factors.

Many efforts have been made to provide either a theoretical basis or an integrated framework for examining influences on smoking initiation. As a step toward an integrated approach, Petraitis and colleagues (1995) suggested that factors affecting tobacco use can be classified along two dimensions-type of influence and level of influence. These authors suggested that three distinct types of influence underlie existing theories of tobacco use-social, cultural, and personal. Social influences include the characteristics, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of the persons who make up the more intimate support system of adolescents, such as family and friends. Cultural influences include the practices and norms of the broader social environment of adolescents, such as the community, neighborhood, and school. Personal influences include individual biological characteristics, personality traits, affective states, and behavioral skills. For each type of influence, three levels of influence-ultimate, distal, and proximal-have been defined by work in evolutionary biology (Alcock 1989), cognitive science (Massaro 1991), and personality theory (Marshall 1991). McKinlay and Marceau (2000a,b) have emphasized the importance of a broad new integration of approaches and multilevel explanations. The levels of influence affect the nature and strength of the type of influence. Ultimate influences are broad, exogenous factors that gradually direct persons toward a behavior but are not strongly predictive. Distal influences are intermediate or indirect factors that may be more predictive. Proximal influences, which are the most immediate precursors of a behavior, are most predictive. The study of social, cultural, and personal domains among adolescents and the various levels of influence has undergone considerable theoretical development. This review of smoking initiation examined more than 100 studies in which tobacco use was an outcome variable. Selected characteristics and major gender-specific findings of the longitudinal studies are shown in Table 4.1.

Table

Table 4.1. Longitudinal studies with gender-specific findings on beliefs, experiences, and behaviors related to smoking initiation.

The primary dependent variables analyzed in the studies differed greatly, ranging from initiation of smoking to amount smoked. The studies most relevant to this report were longitudinal investigations that examined gender-specific results related to smoking initiation among adolescents, including predictors of smoking initiation (Ahlgren et al. 1982; Brunswick and Messeri 1983-84; Skinner et al. 1985; Charlton and Blair 1989; McNeill et al. 1989; Simon et al. 1995), pathways leading to smoking initiation (Flay et al. 1994; Pierce et al. 1996; Pallonen et al. 1998), and predictors of both initiation of and escalation to regular smoking (Chassin et al. 1984, 1986; Santi et al. 1990-91). A few longitudinal studies addressed only escalation to regular smoking (Semmer et al. 1987; Urberg et al. 1991; Hu et al. 1995a). Some cross-sectional studies that compared students who had tried smoking with those who had never tried smoking are also discussed in this text because adolescent smokers are usually recent beginners (USDHHS 1994).

Many of the predictor variables were not defined comparably across studies. Even variables with the same labels may have actually been assessed with different measures. For example, some researchers who studied "school bonding" used attitudinal measures (e.g., attitudes toward school), whereas others used behavioral measures (e.g., truancy). Many studies also examined gender-specific differences in risk factors that predict the frequency or amount of cigarette smoking, not just the initiation of smoking (Kellam et al. 1980; Ensminger et al. 1982; Krohn et al. 1986; Lawrance and Rubinson 1986; Akers et al. 1987; Wills and Vaughan 1989; Waldron and Lye 1990; Bauman et al. 1992; Botvin et al. 1992; Rowe et al. 1992; Winefield et al. 1992; Kandel et al. 1994; Schifano et al. 1994; Sussman et al. 1994).

Social and Environmental Factors

Accessibility of Tobacco Products

Accessibility of tobacco products is an important environmental factor that influences smoking initiation by adolescents (Lynch and Bonnie 1994; USDHHS 1994; Forster and Wolfson 1998). In numerous surveys conducted since the late 1980s, youth often self-reported that their most common source of cigarettes was purchase from retail stores (Lynch and Bonnie 1994; USDHHS 1994; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 1996a,b; Forster and Wolfson 1998). Since the early 1990s, noncommercial or social sources (other minors, parents, older friends) have also been studied (Cummings et al. 1992; CDC 1996b; Forster et al. 1997). Evidence suggested, however, that much of the tobacco provided by minors to other minors was initially purchased from commercial sources by the adolescent donor (Wolfson et al. 1997). Some of these self-report surveys have found that adolescent girls may be less likely than boys to report usually purchasing their own cigarettes (CDC 1996b; Kann et al. 1998). Additionally, results from the Memphis Health Project (Robinson and Klesges 1997) indicated that girls were less likely than boys to view cigarettes as affordable and easy to obtain. Field research concerning minors' access began in the late 1980s and has generally concentrated on assessing rates of illegal sales of tobacco to minors from retail stores during compliance checks in which underage youth attempt to purchase tobacco products (DiFranza et al. 1987; USDHHS 1994; Forster and Wolfson 1998; Forster et al. 1998). Compliance check studies in which both girls and boys participated generally found that retailers were more likely to sell cigarettes to girls than to boys of the same age (Forster and Wolfson 1998).

Pricing of Tobacco Products

Although considerable research has been done on the effect of price on smoking among smokers (Wasserman et al. 1991; Hu et al. 1995b; Chaloupka and Grossman 1996; CDC 1998), little empirical research exists on the effect of price on smoking initiation. Lewit and Coate (1982) used cross-sectional survey data and found that a price increase appeared to affect the decision to become a smoker rather than the decision to smoke less frequently. They also found that the smoking behavior among young adults (20 through 25 years old) was more sensitive to price changes than that among older persons and that male smokers, particularly those aged 20 through 35 years, were quite responsive to price, whereas female smokers were essentially unaffected by price. Chaloupka (1990, 1991a,b) also found that women were much less responsive to price than were men, but, in contrast with the findings of Lewit and Coate (1982), Chaloupka found that adolescents and young adults (aged 17 through 24 years) were less responsive to price than were older age groups. In a CDC (1998) study, data analyzed from 14 years of the National Health Interview Survey showed that a 10-percent increase in price led to a 2.6-percent reduction in the demand for cigarettes among males and a 1.9-percent reduction among females. Thus, females were less responsive to price, as other studies have also found.

Mullahy (1985) found that both the decision to smoke and the quantity of cigarettes consumed by smokers were negatively related to cigarette prices among both men and women. As in the Lewit and Coate (1982) study, Mullahy (1985) found that cigarette prices had a greater effect on the decision to smoke than they did on cigarette consumption. Similarly, he found that men were somewhat more responsive to price than were women (average elasticities of -0.56 and -0.39, respectively). Of the studies that examined price in relation to initiation, two (Lewit et al. 1997; Dee and Evans 1998) found a significant inverse relationship between price and smoking initiation, and one (DeCicca et al. 1998) found no significant relationship. Dee and Evans (1998) estimated the price elasticity of smoking initiation to be in the range of -0.63 to -0.77. This finding implied that for every 10-percent increase in the price of cigarettes, a 6.6- to 7.7- percent reduction in the onset of smoking would be expected. Lewit and colleagues (1997) found that a 10-percent increase in price reduced the onset of smoking by 9.5 percent.

Chaloupka (1992) explored whether differences existed in the impact of clean indoor air laws on cigarette demand among women and men. The results for women and men showed dramatic differences in their response to both clean indoor air laws and cigarette prices. Men living in states with clean indoor air laws were found to smoke significantly less, on average, than their counterparts living in states with no restrictions on smoking. The smoking behavior among women, however, was found to be virtually unaffected by restrictions on cigarette smoking. Increased cigarette prices were found to lower the average cigarette consumption among men, whereas cigarette prices had no impact on smoking among women.

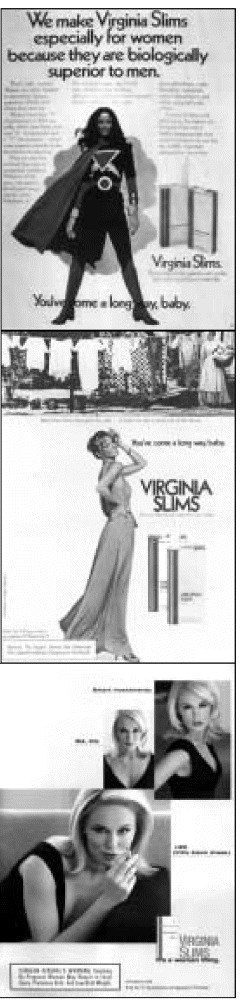

Advertising and Promotion of Tobacco Products

Defining a self-image is an important developmental task during adolescence (French and Perry 1996). Attractive images of young smokers displayed in tobacco advertisements are likely to "implant" the idea of initiation of smoking behavior in adolescent minds as a means to achieve the desired self-image. Therefore, it is not surprising that adolescents generally notice and respond to messages in tobacco advertising and promotion. A study by Pollay and colleagues (1996) found that brand choices among adolescents were significantly related to cigarette advertising and that the relationship between brand choices and brand advertising was stronger among adolescents than among adults.

Gilpin and Pierce (1997) suggested that the tobacco industry's expanded budget for marketing and increased emphasis on marketing tactics that may be particularly pertinent to young people influenced rates of smoking initiation among adolescents. Results from the statewide California Tobacco Survey led Evans and associates (1995) to conclude that tobacco advertising and marketing may have a stronger effect on smoking initiation among adolescents than does exposure to peers and family members who smoke. On the basis of a study of 7th and 8th graders, Botvin and colleagues (1993) reported that exposure to tobacco advertising was predictive of current smoking status. A study performed in rural New England showed that one-third of 6th through 12th graders possessed cigarette promotional items (e.g., T-shirts, hats, and backpacks) (Sargent et al. 1997). Students who owned such items were 4.1 times as likely to be smokers as students who did not own these items. One study revealed that ownership of and willingness to use cigarette promotional items were less common among girls than among boys (Gilpin et al. 1997).

Although advertising is thought to influence smoking initiation, information about differential gender effects of tobacco advertising and promotion on smoking initiation is limited. For a more detailed discussion of the relationship between historic trends in tobacco marketing targeted to women and time trends in smoking among girls and young women, see "Influence of Tobacco Marketing on Smoking Initiation by Females" later in this chapter.

Parental Hostility, Strictness, and Family Conflict

Study results on the effect of parental strictness on smoking initiation among adolescents have been conflicting. Some studies found that strictness and hostility of parents toward their children increased the risk for smoking initiation among adolescent boys (e.g., Chassin et al. 1984). However, other studies concluded that perception of parental strictness by adolescent children did not contribute to smoking initiation (e.g., McNeill et al. 1989).

Biglan and coworkers (1995) studied a sample of 643 adolescents at three time intervals. Family conflict at time 1 predicted inadequate parental monitoring at time 2, and inadequate parental monitoring, association with deviant peers, parental smoking, and peer smoking at time 2 predicted smoking at time 3. The model was the same for girls and boys, and no significant differences were found in the path coefficients. These findings suggested that family conflict influences tobacco use indirectly and that the mechanism among girls and boys is similar.

Level of Parental Supervision, Involvement, or Attachment

Parents who closely supervise their children know where their children are and monitor what they are doing. Results of some studies suggested that close supervision deters smoking among adolescents (Chassin et al. 1986; Mittelmark et al. 1987; Radziszewska et al. 1996; Jackson et al. 1997), and findings in two studies suggested that parental supervision may be a greater deterrent among girls than among boys (Skinner et al. 1985; Krohn et al. 1986). This pattern might be explained by the finding that girls are generally monitored more closely than are boys (Cohen et al. 1994). One study revealed that authoritative parenting styles influenced children's smoking initiation independently of parental smoking status (Jackson et al. 1994). However, other studies showed no link between parental supervision and adolescent smoking (e.g., Krohn et al. 1983).

Parental involvement implies the active participation of parents in their children's lives. A longitudinal study of fifth and seventh graders found lower rates of smoking initiation among children who reported that their parents spent more time with them and communicated with them more frequently (Cohen et al. 1994). Girls tended to have better communication with their parents than did boys, but the relationship between interaction with parents and smoking initiation was not reported separately by gender. In one study, parental involvement in their children's school, religious, and athletic activities decreased the risk for smoking among both girls and boys (Krohn et al. 1986). In another study, children who perceived their parents as generally unconcerned about their social activities were slightly more likely to increase their smoking over a one-year period (Murray et al. 1983). The results of two other studies suggested, however, that this relationship may exist for boys only (Mittelmark et al. 1987; Stanton et al. 1995).

Longitudinal studies have reported that the risk for smoking among adolescents increases as their emotional bonds and sense of attachment to parents weaken (Conrad et al. 1992). Findings in several studies suggested that weak attachment to parents and risk for smoking do not differ by gender (Ensminger et al. 1982; Krohn et al. 1986; Kumpfer and Turner 1990-91). One study of female college students found that poor father-daughter relationships (e.g., spending little time together or poor communication) correlated with the daughters' smoking (Brook et al. 1987).

Parental Smoking

Parents who smoke are more likely than those who do not to have children who smoke (Conrad et al. 1992; Jackson et al. 1997). Studies found that children in grades four through six (mean age, 11 years) were almost three times as likely to have smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days if they lived with an adult smoker (Morris et al. 1993) and that adolescents were about two times as likely to have smoked daily if one or both parents smoked (Green et al. 1991). One study found that adolescents whose parents had stopped smoking were about one-third less likely to have ever smoked than were those with parents who still smoked (Farkas et al. 1999). Several studies reported that girls and boys are equally susceptible to the effects of parental smoking (Chassin et al. 1984; Santi et al. 1990-91; Green et al. 1991; Glendinning et al. 1994) and to parental attitudes toward smoking (Ary and Biglan 1988). However, some researchers found differences in receptivity to parental smoking among girls and boys. One study showed that boys were more influenced by parental smoking than were girls (Sussman et al. 1987), but most of the studies suggested that girls may be more influenced than boys (Chassin et al. 1986; Charlton and Blair 1989; Swan et al. 1990; van Roosmalen and McDaniel 1992; Flay et al. 1994; Kandel et al. 1994; Hu et al. 1995a; Robinson et al. 1997).

The effects of maternal smoking may differ among girls and boys. In three studies, maternal smoking tended to have a slightly greater effect on subsequent smoking among girls than among boys (Ahlgren et al. 1982; Pulkkinen 1982; Bauman et al. 1992). This finding was confirmed in a study of 201 parent-child triads that used independent reporting of smoking status from each member of the domestic group (Kandel and Wu 1995), unlike the majority of studies, which used the child's report about parents' smoking. Stanton and Silva (1992) reported that recent smoking cessation among mothers apparently helped to delay and perhaps deter smoking among daughters but not among sons. Thus, adolescent girls may be more likely than adolescent boys to model their smoking on their mothers' smoking behavior. In one study, however, maternal smoking significantly predicted smoking among sons but not among daughters (Skinner et al. 1985).

Sibling Smoking

One study reported that smoking among older siblings had little or no influence on smoking among their younger sisters and brothers (Ary and Biglan 1988), but other evidence suggested that young siblings are influenced by sibling smoking (Swan et al. 1990; Conrad et al. 1992; Daly et al. 1993). The effect was equal among girls and boys in one study (Santi et al. 1990-91). In other studies, the effect was stronger among girls (Chassin et al. 1984; Mittelmark et al. 1987; van Roosmalen and McDaniel 1992; Pierce et al. 1993) or among boys (Brunswick and Messeri 1983-84; Stanton and Silva 1991). The pattern may vary by race or ethnicity (Hunter et al. 1987); in particular, African American girls appeared to be less susceptible than white girls to the influence of siblings, other family members, and peers who smoked. At present, no conclusion can be drawn about the comparative susceptibility of girls and boys to sibling smoking.

Peer Smoking

In many studies, one of the strongest risk factors for smoking is exposure to peers, especially close friends, who smoke (USDHHS 1994; Meijer et al. 1996; Gritz et al. 1998). Friends' smoking was predictive of some phase of smoking in all but 1 (Newcomb et al. 1989) of 16 longitudinal studies reviewed by Conrad and associates (1992). Results of many studies suggested that involvement with peers who smoke has a similar effect among girls and boys (Palmer 1970; McCaul et al. 1982; Pulkkinen 1982; Chassin et al. 1984), 1986; Gottlieb and Baker 1986; Krohn et al. 1986; Mittelmark et al. 1987; Sussman et al. 1987; Santi et al. 1990-91; Stanton and Silva 1992; Urberg 1992; van Roosmalen and McDaniel 1992; McGee and Stanton 1993; Pierce et al. 1993; Glendinning et al. 1994). Findings in other studies suggested that peer smoking affects adolescent girls and boys somewhat differently. In a few studies, boys who smoked had more friends who were smokers (Morris et al. 1993) and were more influenced by the smoking-related attitudes (Chassin et al. 1984) and behaviors of their peers than were girls who smoked (Urberg et al. 1991). However, most of the studies that reported gender-specific differences suggested that girls are more influenced by peer smoking than are boys (Semmer et al. 1987; Charlton and Blair 1989; Pirie et al. 1991; Waldron et al. 1991; Rowe et al. 1992; Sarason et al. 1992; Skinner and Krohn 1992; Hu et al. 1995a). Akers and colleagues (1987) reported that adolescent girls were more influenced in their smoking behavior by their boyfriends than adolescent boys were influenced by their girlfriends. However, Skinner and associates (1985) found that the initiation of smoking among girls tended to coincide with increasing involvement with other girls who smoked but not with boys who smoked.

Bauman and Ennett (1994) contended that the examination of simple peer associations may be less revealing than the exploration of social networks among peers. These researchers and their colleagues pointed to the homogeneity of adolescent friendship cliques with regard to smoking and noted that, in a formal network analysis of 87 such cliques, most were composed entirely of nonsmokers (Ennett et al. 1994). The study results suggested that cliques may contribute more to the maintenance of nonsmoking status than to the initiation of smoking. These findings were strongest among all-female and among all-white cliques. In another analysis of the same data, the authors pointed out that adolescents who did not belong to a clique had a higher probability of smoking than did adolescents who belonged to a clique (Ennett and Bauman 1993).

Perceived Norms and Prevalence of Smoking

Adolescents whose close peers smoke tend to perceive that smoking is far more normative than it actually is (Conrad et al. 1992; USDHHS 1994). One study revealed that seventh-grade girls estimated the overall incidence of smoking among their peers at significantly higher levels than did seventh-grade boys (Robinson and Klesges 1997). At least three studies have examined gender-specific differences in perceived social norms of adolescent smoking and smoking initiation. In two studies, significantly more females than males reported social norms as a reason for experimenting with cigarettes or beginning to smoke (Botvin et al. 1992; Sarason et al. 1992). In the third study, the opposite gender-specific effect was observed (Chassin et al. 1984).

Perceived Peer Attitudes Toward Smoking

In one study of a multiethnic sample of adolescents, perceived approval of smoking by one's three best friends was significantly associated with susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking (Gritz et al. 1998). In other studies, even though boys reported more often than girls that their friends' approval of smoking was an important influence on their smoking, peer smoking appeared to be an equally strong risk factor for smoking among girls and boys (Pierce et al. 1993; Flay et al. 1994).

Strong Attachment to Peers

Among adolescents, strong bonds with parents tend to deter smoking, and strong bonds with peers tend to promote smoking. Indeed, Conrad and colleagues (1992) found that in nine longitudinal studies, adolescents were more likely to experiment with cigarettes or to start smoking regularly if they had developed close emotional attachments to other adolescents, spent more and more time with friends, had a large number of close friends, reported that agreement with peers was increasingly important, or had a boyfriend or girlfriend (Kellam et al. 1980; Ahlgren et al. 1982; Krohn et al. 1983; Murray et al. 1983; Chassin et al. 1984; Skinner et al. 1985; Semmer et al. 1987; Sussman et al. 1987; McNeill et al. 1989). Several studies have reported no gender-specific differences in the effects of peer bonds on smoking (McNeill et al. 1989; Swan et al. 1990; Sussman et al. 1994). One study among African Americans, however, showed that the number of close friends an adolescent reported having was a predictor of smoking initiation for boys only (Brunswick and Messeri 1983 -84). In another study, positive social events and peer support increased the likelihood of smoking among more girls than boys (Wills 1986), and Best and colleagues (1995) suggested that among adolescents for whom peer approval is especially important, girls may be more likely than boys to smoke.

Interaction of Social Influences

Flay and associates (1994) tested a model that examined how the following factors interact to influence smoking initiation among adolescents: (1) friends' smoking, (2) parental smoking, (3) expectation of negative outcome from smoking, (4) perceived friends' approval of smoking, (5) perceived parental approval of smoking, (6) refusal self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in one's ability to resist temptations to try smoking), and (7) intention to smoke or not to smoke. The findings showed that friends' smoking influenced smoking initiation both directly and indirectly and that friends' smoking was a stronger influence than parental smoking. Parental smoking had a stronger effect among girls than among boys, but this gender-specific influence was tempered by parental approval or disapproval of smoking. Disapproval mediated the influence of parental smoking among girls but not among boys, and parental approval was an important predictor that girls would start to smoke. These results are consistent with other findings that girls may be more susceptible than boys to social influences, especially parental influences (see "Parental Smoking" earlier in this chapter). No significant gender-specific differences were observed in how the pathways from self-efficacy and expectations of negative outcome affected smoking initiation.

Previous research suggested that parental influence, in general, remains constant or decreases but that the influence of peers increases as adolescents develop (e.g., Krosnick and Judd 1982). A more recent study indicated that the pattern of change in parental and peer influences on smoking may differ among girls and boys (Hu et al. 1995a). In this longitudinal study, data were collected at four time points from grades seven through nine. Smoking status was predicted by using previous smoking status and the effects of time, friends' smoking, and parental smoking. In general, the effects of friends' smoking were stronger than the influence of parental smoking, and the effects of friends' smoking appeared to increase over time, whereas the influence of parental smoking remained fairly constant. Although parental smoking predicted initiation and escalation of smoking equally, friends' smoking was more predictive of initiation than of escalation. The effects of friends' smoking were stronger among girls than among boys, and the tendency for the influence of friends to increase with time was also more noticeable among girls.

Pederson and colleagues (1998) examined the dose-response relationships between various social variables (e.g., maternal smoking, parental approval of smoking, sibling smoking, and friends' smoking) and smoking status among eighth-grade students. The study revealed strong dose-response relationships between these social variables and smoking status for the entire group and, in most cases, among females and males when data were analyzed separately.

Personal Characteristics

Socioeconomic Status and Parental Education

Several studies have shown that low socioeconomic status puts adolescents at higher risk for smoking (Conrad et al. 1992; USDHHS 1994). At least three studies have examined whether the risk for smoking among daughters and sons is affected differently by the socioeconomic status of their parents. Findings in two studies suggested that low socioeconomic status places girls at higher risk than boys (Chassin et al. 1992; Glendinning et al. 1994). The third study produced a contrary finding, but it was conducted among college students, a group in which low socioeconomic status may have been underrepresented (Gottlieb and Baker 1986).

National surveys consistently showed that education (number of years of schooling) is inversely related to cigarette smoking among women and men (see Chapter 2). However, data from the Monitoring the Future Surveys provided little evidence of a gender-specific effect of parental education on risk for smoking among high school seniors for the period 1994-1998. Among seniors whose parents had not graduated from high school, females were more likely than males to smoke, but in general the prevalence of current smoking among both females and males differed little across level of parental education (see "Relationship of Smoking to Sociodemographic Factors" in Chapter 2 and Table 2.11).

Ferrence (1988) proposed a model of diffusion of innovations (Rogers and Shoemaker 1971) to help elucidate gender-specific differences in relation to initiation and cessation of smoking. In general, persons with better economic resources, more education, and greater power adopt new ideas and behaviors and accumulate material goods earlier than those with fewer such resources. This fact may explain why men historically started smoking before women did. Gender-specific differences in relation to economic resources, education, and power have changed over time in concert with changes in the roles of women in society. The first women to smoke were those who, by virtue of their resources, were considered avantgarde. Similarly, in recent decades, the reduction in smoking prevalence occurred first among persons having greater resources. This explanation is supported by theories on social roles (Dicken 1978, 1982; Deaux and Major 1987; Eagly 1987; Waldron 1991).

Behavioral Control

Theories on smoking and drug use (Petraitis et al. 1995) contend that persons may be unable to resist temptations to smoke if they are unable to control certain other behaviors, including tendencies to be impulsive, easily distracted, or aggressive or to exhibit type A behavior. Studies have shown that smoking was more common among (1) adolescents who reported getting into trouble at school (Krohn et al. 1986); (2) young adults who had been aggressive, quarrelsome, and impatient at age 8 years (Pulkkinen 1982); (3) young adults who as children did not solve problems reasonably, did not negotiate with others, and were not conciliatory toward others (Pulkkinen 1982); and (4) adults who demonstrated type A behavior (Forgays et al. 1993).

Results in several studies suggested that a lack of behavioral control plays a larger role in smoking among girls than among boys. Aggressive behavior may put girls at significantly higher risk than boys for succumbing to peer pressures to smoke (Stanton et al. 1995). In one study, young women, but not young men, were more likely to initiate smoking as adolescents if they focused more on short-term goals than on long-term goals (Brunswick and Messeri 1983-84).

Sociability

Adolescents who are shy or lack social skills may find it especially difficult to resist peer pressure to smoke. Studies indicated that adolescents may view smoking as a vehicle for entering a desired friendship group (e.g., Aloise-Young et al. 1994), but two studies suggested that this is true only among boys (Gottlieb and Green 1984; Allen et al. 1994). In a study of girl and boy smokers and nonsmokers, Allen and coworkers (1994) concluded that adolescent boys may have used smoking to cope with social insecurity, whereas adolescent girls who smoked were more socially competent and self-confident than were girls who did not smoke. Killen and colleagues (1997) also found that sociability was related to smoking initiation among adolescent girls.

Fatalism and External Locus of Control

Persons who have an external locus of control generally believe that their lives are controlled by external forces (e.g., fate or God) and may believe that they can do little to prevent negative events from affecting them. In one study, investigators found no link between locus of control during adolescence and smoking during adulthood (Winefield et al. 1992). Other studies, however, suggested that fatalism and an external locus of control are associated with smoking initiation (Brunswick and Messeri 1984; Chassin et al. 1984).

Intelligence, Academic Performance, and Commitment to School

In their analysis of data from the 1990 California Youth Tobacco Survey, Hu and colleagues (1998) found that students who reported their performance in school as below average were more likely than better-than-average students to be current or former smokers. They found no gender-specific differences in the likelihood of being a former smoker or in attempts to stop smoking. An earlier study found that scores on tests of intelligence and readiness for school during first grade were not related to smoking among 16- and 17-year-old African American girls or boys (Kellam et al. 1980). Another study of adolescents reported that poorer academic achievement increased the risk for smoking among girls and boys, but that the importance of two achievement measures differed; reading test scores were stronger predictors among girls, whereas grade point average better predicted smoking among boys (Brunswick and Messeri 1983-84, 1984).

Weak commitment to school consistently predicts the initiation and progression of smoking among adolescents (Conrad et al. 1992). In one longitudinal study, investigators found no gender-specific difference in the effect of weak school bonds on subsequent smoking (Ensminger et al. 1982). However, three other studies suggested that commitment to school affects girls more strongly than it affects boys (Hibbett and Fogelman 1990; Waldron et al. 1991; Skinner and Krohn 1992), and one study reported the reverse (Chassin et al. 1984). Because of these conflicting findings, no conclusion can be drawn about gender-specific differences in relation to school bonds and adolescent smoking.

Rebelliousness, Risk Taking, and Other Health-Related Behaviors

Longitudinal studies of smoking consistently have shown that adolescents are at risk for smoking if they previously rebelled against rules, teachers, or adults in general (Mittelmark et al. 1987); opposed disciplinary rules at school (Murray et al. 1983); or tolerated deviant behavior in others (Chassin et al. 1984). Although adolescent rebelliousness appears to be less common among girls than among boys (Robinson and Klesges 1997), findings in some longitudinal studies suggested that rebelliousness and tolerance for unconventional behavior may affect smoking initiation among girls and boys equally (Skinner and Krohn 1992; Simon et al. 1995). However, several studies have shown that smoking was more highly correlated among girls than among boys in regard to the following characteristics: rebelliousness (Pierce et al. 1993), feelings of being decreasingly bound by laws and parental rules (Skinner et al. 1985), higher levels of both rebelliousness and rejection of adult authority (Best et al. 1995), and tolerance of deviant behavior (Chassin et al. 1984). Stanton and colleagues (1995) found that delinquency significantly increased the risk for smoking among girls but was not related to smoking among boys. One study found that 17-year-old girls were more likely than boys the same age to smoke experimentally if they went to bars, taverns, or nightclubs; had been in trouble with the police; or had been involved in fights (Waldron et al. 1991). Findings from this study paralleled earlier reports about rebelliousness (Sussman et al. 1987).

Sensation seeking has been defined as willingness to take risks for the sake of stimulation and arousal (Zuckerman et al. 1987). Sensation seeking and risk taking appear to be related to smoking among adolescents (Simon et al. 1995; Petridou et al. 1997; Wahlgren et al. 1997; Coogan et al. 1998).

Clustering of smoking and other unhealthy behaviors suggested the formation of a "risk behavior syndrome" during adolescence (Escobedo et al. 1997). This syndrome may emerge as early as elementary school (Coogan et al. 1998). Data from the National Health Interview Survey indicated that smoking aggregates with marijuana use, binge drinking, and fighting among African Americans, Hispanics, and whites of both genders (Escobedo et al. 1997). Other U.S. national survey data also showed a strong relationship between smoking and use of other substances, including alcohol, among girls and young women (see Chapter 2). A British study examined smoking status, exercise, and dietary behaviors among 14- and 15-year-old adolescents (Coulson et al. 1997). Smoking was associated with lower levels of exercise, lower consumption of fruits and vegetables, and greater consumption of high-fat foods. In addition, evidence from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey suggested that participating in interscholastic sports inhibits the development of regular and heavy smoking among adolescents (Escobedo et al. 1993). Furthermore, some studies reported that the more physically active and fit adolescent girls were, the less likely they were to initiate smoking (e.g., Waldron et al. 1991; Aaron et al. 1995). A British study found that girls who had a teenage pregnancy were more likely to smoke cigarettes than were girls who had not been pregnant (Seamark and Gray 1998).

Results from the longitudinal Minnesota Heart Health Program provided evidence that smoking, physical inactivity, and poor dietary preferences cluster in childhood and tend to endure through adolescence (Kelder et al. 1994; Lytle et al. 1995). Similar clustering of smoking and other unhealthy behaviors were reported in an Australian study with follow-up on a cohort of persons aged 9 years through early adulthood (Burke et al. 1997). At age 18 years, smoking, excessive alcohol use, and poor dietary preferences were clustered among both women and men; physical inactivity was also part of the cluster among women.

Religiousness

Most studies on the relationship between religiousness and smoking suggested that religious beliefs are important in the decision of some persons not to smoke. After age 17 years, young women who attended church only occasionally were more than twice as likely to start smoking as were those who attended regularly (Daly et al. 1993). In general, more women than men report religious commitment, which appears to be associated with a lower rate of smoking among women (Reynolds and Nichols 1976; Brook et al. 1987; Grunberg et al. 1991; Waldron 1991). Study data indicated that among high school seniors of both genders, the prevalence of smoking is inversely related to the self-reported importance of religion (see "Relationship of Smoking to Sociodemographic Factors" in Chapter 2). In three studies that examined gender-specific differences in religious attitudes among adolescents, religion deterred smoking among females more than it did among males, and a lack of religious commitment contributed to smoking among females more than it did among males (Gottlieb and Green 1984; Krohn et al. 1986; Waldron et al. 1991). In contrast, Skinner and colleagues (1985) found that religiousness had no effect on smoking by either gender.

Self-Esteem

Adolescents who have poor self-esteem may have difficulty resisting pressures to smoke, especially if they believe that smoking will enhance their image. In some longitudinal studies, adolescents with low self-esteem were significantly more likely than those with high self-esteem to start smoking within the next year (Ahlgren et al. 1982; Simon et al. 1995). Other longitudinal studies, however, detected no link between self-esteem and subsequent smoking (Brunswick and Messeri 1983 -84; Winefield et al. 1992). One study showed that girls who scored high on personal dissatisfaction (e.g., desire to have more friends, be thinner, or be less socially anxious) were more likely to smoke than were girls who appeared to be more personally satisfied (Best et al. 1995). This relationship between personal dissatisfaction and smoking was not observed among boys. Similar findings from another study suggested that self-esteem may be a factor in the smoking behavior among girls in grades six through eight but not among males in any grade (Abernathy et al. 1995).

Emotional Distress

Theories of smoking and drug use have suggested that persons may have difficulty resisting temptations to smoke if they are anxious, hostile, irritable, depressed, or psychologically distressed (Petraitis et al. 1995). Evidence of a link between emotional distress and smoking is mixed, however. Many of the studies have focused on adults, so it is not clear to what extent the findings can be extrapolated to smoking initiation, which generally occurs among adolescents. Some investigators have found no association between smoking, hopelessness, stress, nervousness, negative mood, psychological disturbances, or level of anxiety (Winefield et al. 1992; Simon et al. 1995). Others have found links between smoking and anger (Modrcin-McCarthy and Tollett 1993); stress (Wills 1986); stressful life events (Frone et al. 1994); depression (Pederson et al. 1998); and anxiety levels, physical complaints, and hostility (Forgays et al. 1993; Schifano et al. 1994). A study by Johnson and Gilbert (1991) reported that the intense feelings of anger and irritability were related to both smoking initiation and maintenance among African American adolescents, whereas among white adolescents these emotions were associated only with smoking initiation. One qualitative investigation reported that the most frequent reasons for smoking among girls in grades 10 and 11 were stress reduction and relaxation (Nichter et al. 1997). Although exceptions have been reported (Oleckno and Blacconiere 1990; Allen et al. 1994; Frone et al. 1994), findings in several studies suggested that symptoms of distress are more strongly associated with smoking among females than among males (Brunswick and Messeri 1984; Gottlieb and Green 1984; Knott 1984; Semmer et al. 1987; Lee et al. 1988; Waldron et al. 1991; Pierce et al. 1993).

Coping Styles

Two studies have examined whether there are gender-specific differences in the link between smoking levels and the way persons cope with their problems, but such differences do not appear to exist. In one study, MacLean and coworkers (1996) found no connection between smoking level during the past month and the frequency with which 17-year-old girls and boys used various strategies (e.g., getting angry) to cope with problems. In a study of 12-year-olds, Wills and Vaughan (1989) examined the relationship between current smoking and earlier tendencies to seek adult or parental help with problems, but they found no differences by gender in this relationship. These researchers did find that, among adolescents who had previously relied on peers for help with problems, girls were far more likely than boys to smoke, but it is unclear whether this effect related primarily to coping styles or to peer attachments.

Perceived Refusal Skills

Adolescents who are confident of their ability to resist pressures to smoke may be better able to avoid smoking than those who are not confident. Although girls may have stronger doubts about avoiding cigarette smoking in the future than do boys (van Roosmalen and McDaniel 1992), attempts to reduce those doubts appear to have the same effect among girls and boys. Findings in experimental studies suggested that refusal skills can be taught effectively to both girls and boys (Sallis et al. 1990), and results of longitudinal studies suggested that self-doubts about the ability to refuse offers to smoke affect girls and boys equally (Lawrance and Rubinson 1986; Flay et al. 1994). In one study, however, this finding was not true among all racial and ethnic groups; for 13-year-old Asian children who one year earlier had doubted their ability to refuse an offer of a cigarette, the prevalence of smoking was higher among boys than among girls (Sussman et al. 1987).

Previous Experimentation with Tobacco and Intention to Smoke

Findings in three longitudinal studies suggested that girls and boys who experiment with cigarettes during adolescence are at generally similar risk for progression from experimentation to regular smoking. In two of these studies, the investigators found no gender-specific differences in the link between experimental smoking during adolescence and regular smoking during early adulthood (Chassin et al. 1990; McGee and Stanton 1993). In the third study, the researchers found that the amount smoked at ages 10 through 13 years was strongly related to the amount smoked at ages 14 through 17 years and that the link between previous and current smoking may have been stronger among boys than among girls (Skinner and Krohn 1992). Two studies showed that girls and boys were equally likely to smoke if at least one year earlier they had thought they might smoke in the future (Ary and Biglan 1988; McNeill et al. 1989). In a large study of 4,500 adolescents, the lack of a firm decision not to smoke was a strong baseline predictor of both experimentation and progression to regular smoking (Pierce et al. 1996). However, intention was not as important as exposure to other smokers in influencing the transition from experimentation to regular smoking. No gender differences were found.

Susceptibility to Smoking

As smoking prevention moves toward use of more tailored and individualized programs, identifying precursors of smoking initiation becomes increasingly important. The ability to classify adolescents as being at higher or at lower risk for smoking initiation is critical to the development of appropriate intervention techniques.

Two theoretical concepts appear to be particularly useful for identifying adolescents at risk for smoking initiation: the transtheoretical model of change (Prochaska et al. 1992; Pallonen 1998; Pallonen et al. 1998) and susceptibility to smoking (Pierce et al. 1996). The transtheoretical model of change postulates gradual progression through a series of discrete stages of cognitive and behavioral change, simultaneously integrating constructs such as stages of change, decisional balance (pros and cons of smoking behavior), situational temptations to try smoking (Hudmon et al. 1997), and self-efficacy. Pallonen and colleagues (1998) proposed integration of the stages of adolescent smoking initiation and cessation. The four stages of smoking initiation are (1) acquisitionprecontemplation, (2) acquisition-contemplation, (3) acquisition-preparation, and (4) recent acquisition. These stages have been validated in a sample of high school students. The scores for perceived advantages (pros) of smoking and temptations to try smoking were closely related to the stages of smoking initiation. The continuum based on the four stages of change appears to provide a concise and theoretically sound approach to smoking initiation in adolescent populations.

Susceptibility to smoking is a measure of intention to smoke. According to this concept, "susceptible" adolescents exhibit a lack of firm commitment not to smoke in the future. The construct of susceptibility to smoking has been used in the California Tobacco Survey and other studies; its rationale and validation have been extensively presented in the literature ( Pierce et al. 1995, 1996; Unger et al. 1997; Jackson 1998). Adolescents are susceptible to smoking if they have made no determined decision not to smoke in the next year or if offered a cigarette by a friend. The susceptibility measure integrates intentions and expectations of future behavior; therefore, it identifies persons with a cognitive predisposition to smoking. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that susceptibility is a stronger predictor of smoking experimentation among both females and males than are other well-established predictors, such as exposure to smokers in the immediate social environment (Pierce et al. 1996; Jackson 1998). A recent study reported that the susceptibility construct can predict who among adolescent experimental smokers will become established smokers (Distefan et al. 1998).

Expectations of Personal Effects of Smoking

Beliefs About Effects on Image and Health

In several longitudinal studies of smoking among adolescents, smoking was more common among persons who lacked knowledge of the health consequences of smoking, doubted that nicotine is addictive, and had mostly positive beliefs about smoking (Conrad et al. 1992). Attitudes that put adolescents at risk for smoking included (1) having tolerance for smoking by others, (2) believing that smoking makes people look good and enhances their image, (3) having the opinion that smoking is fun or pleasant, (4) expecting generally positive consequences from smoking, and (5) placing more value on the perceived positive results of smoking than on the negative consequences. The belief that smoking makes people have an unpleasant smell, look silly, or feel sick reduced the risk for smoking.

Evidence suggested that some attitudes about smoking are especially important among girls. In some studies, girls were found to be at higher risk than boys for smoking if they thought the harmful effects of smoking had been exaggerated (Waldron et al. 1991) or if they dismissed the health hazards of smoking (Swan et al. 1990). In a study of persons 18 through 23 years old, thoughts about health were an important deterrent to smoking among women but not among men (Brunswick and Messeri 1983-84). However, another study showed that boys expected more benefits from smoking than did girls and that the relationship between the expected number of benefits and susceptibility to smoking was stronger among boys than among girls (Pierce et al. 1993).

Findings have been inconclusive on genderspecific differences in whether smokers are perceived to be mature, confident, and self-reliant. In one study, this image was positively associated with smoking among both girls and boys (McGee and Stanton 1993), but in two other studies, such an image was more important among girls than among boys (Mittelmark et al. 1987; Waldron et al. 1991), while in another study such an image was more important among boys than among girls (Dinh et al. 1995).

Concerns About Weight Control

Many girls believe that smoking helps to control weight by suppressing appetite (USDHHS 1980; Klesges et al. 1989, 1997). Findings in several crosssectional studies suggested that concerns about body weight and dieting are related to smoking status among adolescent girls (Charlton 1984; Gritz and Crane 1991; Pirie et al. 1991). Among 1,915 students in grades 10 through 12 in one school district in Mississippi, girls who smoked were more likely than girls who did not smoke to perceive themselves as fat (Page et al. 1993). This association was not found among boys. Both girls and boys who smoked were less satisfied with their weight than were nonsmokers. A study of Catholic high school students in Memphis, Tennessee, found that among white students who smoked more than once a week, girls (39 percent) were significantly more likely than boys (12 percent) to use smoking in an attempt to control weight (Camp et al. 1993). A longitudinal study of 1,705 students in grades 7 through 10 indicated that concerns about weight and dieting behaviors (e.g., constant thoughts about weight and trying to lose weight) were positively related to smoking initiation among girls but not among boys (French et al. 1994). At baseline, fear of gaining weight, the desire to be thin, and trying to lose weight were also positively related to current smoking among girls.

Although most of these studies reported a relationship between smoking status and concerns about weight, investigators in only one study (Camp et al. 1993) controlled for many other known correlates of smoking: age, race and ethnicity, number of smoking models (e.g., peers who smoke), perceived value of smoking, degree of social support, risk-taking behavior, rebelliousness, and pharmacologic and emotional reactions to early experimentation with smoking. In that study, being female predicted smoking for weight control reasons.

Most of these studies on adolescents' beliefs about smoking and weight control were conducted primarily or exclusively among white study participants. The processes of smoking initiation may be different across racial and ethnic groups (Flay et al. 1994; Klesges and Robinson 1995). For example, according to a school-based survey conducted in the early 1980s, concerns about weight and dieting may have been less important among African American girls than among white girls (Sussman et al. 1987). In a survey of 6,967 seventh-grade adolescents in an urban school system, Robinson and colleagues (1997) found that African American adolescents who knew about the weight-suppressing effect of smoking were less likely to experiment with cigarettes than were those who believed that smoking had no effect on weight. Among white adolescents, weight control beliefs were not associated with cigarette experimentation. No gender differences were reported.

Beliefs About Mood Control and Depression

The belief that smoking can control negative moods and produce positive moods is important among many girls. One study showed that girls were no more likely than boys to smoke for relaxation or relief from problems or anxieties (McGee and Stanton 1993). However, at least two studies showed that females were more likely than males to say that they smoked to control negative emotions (Semmer et al. 1987; Novacek et al. 1991). Pirie and associates (1991) also found that young women who smoked were significantly more likely than young men who smoked to say that they would be tense and irritable if they stopped smoking.

Depression in adolescence predicts depression in young adulthood (Kandel and Davies 1986) and may have an important interrelationship with smoking. Among adults, major depression is strongly related to smoking (Anda et al. 1990; Glassman et al. 1990; Kendler et al. 1993), although neither the directionality of the association nor its gender-specific effect is completely understood. Findings in a large cross-sectional study suggested that depression and anxiety were associated with smoking among teenage girls of all ages but only among younger teenage boys (Patton et al. 1996). Astudy in Atlanta of 1,731 youths aged 8 through 14 years who were assessed at least twice from 1989 through 1994 found that antecedent tobacco smoking was associated with an increased risk for subsequent depressed mood but that antecedent depressed mood was not associated with risk for subsequently initiating smoking (Wu and Anthony 1999). Findings were not presented separately by gender, but gender was included in multivariate analyses and was not an independent predictor of smoking initiation. (See "Depression and Other Psychiatric Disorders" in Chapter 3.)

Biological Factors

A growing body of research has explored the interaction between genetic and environmental influences on both initiation and maintenance of smoking (reviewed by Heath and Madden 1995); this work has often been based on complex statistical and genetic models. Studies of monozygotic and dizygotic twins (Boomsa et al. 1994; Maes et al. 1999) or of twins reared apart and reared together (Kendler et al. 2000) suggested that heritable factors account for a substantial proportion of the observed variation in tobacco use, although the range of estimates across studies is wide.

Epidemiologic studies among adults provided additional evidence of genetic predisposition to cigarette smoking. For example, Spitz and associates (1998) reported that patients with lung cancer who had genetic polymorphism at the locus for the D2 dopamine receptor were more likely to have started smoking at an earlier age and to have smoked more heavily than those without the polymorphism. Lerman and colleagues (1999) reported that the dopamine transporter gene, SLC6A3-9, may influence smoking initiation before the age of 16 years, but gender-specific results were not reported. Currently this is an active area of investigation, and further exploration of genetic factors, particularly in racially and ethnically diverse populations, is warranted.

Some studies suggested gender differences in nicotine metabolism (Grunberg et al. 1991) or suggested that women trying to quit are more likely to report withdrawal symptoms than are men (Gritz et al. 1996) or are likely to recall their withdrawal symptoms as more severe than do men (Pomerleau et al. 1994). However, it appears that differences in metabolism may not exist once amount of smoking is controlled for (see "Nicotine Pharmacology and Addiction" in Chapter 3), and it is unclear whether differences in withdrawal responses are subjective or physiologic (Niaura et al. 1998; Eissenberg et al. 1999). Sussman and colleagues (1998) reported that adolescent female smokers were more likely than their male counterparts to report having difficulty going a day without smoking, but it is not known whether any gender differences related to nicotine metabolism or sensitivity exist that affect initiation.

Little is known about whether endogenous hormones affect the likelihood of smoking initiation among females. The findings of Bauman and colleagues (1992) suggested that testosterone levels among girls but not among boys increase receptivity to the influence of maternal smoking-girls with relatively high testosterone levels may be more likely than girls with low testosterone levels to model their mothers' smoking behavior. Using blood samples obtained from a cohort of pregnant women in the 1960s, Kandel and Udry (1999) reported a positive correlation between maternal prenatal testosterone levels and subsequent smoking among female off-spring at adolescence. Also, early onset of puberty may prompt girls to smoke (Wilson et al. 1994); this phenomenon may reflect either hormonal levels or social pressures associated with early puberty. Further research is needed to determine whether hormones influence smoking initiation.

Summary

This qualitative assessment revealed a considerable degree of inconsistency in research findings across studies that have examined gender-specific differences in smoking initiation. Some of the inconsistency resulted from differences in the study populations examined and from differences in study design and quality. However, considering the literature as a whole, certain conclusions seem warranted. Most risk factors for smoking initiation appear to be similar among girls and boys. Evidence indicated that strength of attachment to family and friends and smoking by parents and peers have considerable influence on smoking initiation, but study results were inconsistent, which makes it not possible to conclude that girls and boys are differentially affected by such factors. Likewise, perceptions about norms, prevalence of smoking, and attitudes of peers toward smoking, as well as commitment to school, are strong predictors of smoking initiation; whether they affect girls and boys differently is unclear. Some studies suggested that girls are more likely than boys to smoke if they are rebellious, reject conventional values, or lack commitment to religion. Others suggested that poor self-esteem and emotional distress are more strongly associated with smoking initiation among girls than among boys. Among girls, however, those who are more sociable appear to be at higher risk for smoking initiation than are less socially confident girls. Girls also appear to be especially affected by a positive image of smoking, desire for weight control, and the perception that smoking controls negative moods. Both genders appear similarly affected by coping style, poor refusal skills, low self-efficacy, previous use of tobacco, and intention to smoke. Studies of genetic and hormonal factors in relation to smoking initiation have only recently begun, and it is premature to draw conclusions regarding gender-specific differences related to such factors. Advertising and promotion of tobacco products also affect the likelihood of initiation (see "Influence of Tobacco Marketing on Smoking Initiation by Females" later in this chapter).

Factors Influencing Maintenance or Cessation of Smoking

Overview of the Studies Examined

Factors that influence continuation of smoking exert an effect throughout the lives of smokers. The interrelationship of these factors is complex, but the data on maintenance or cessation of smoking have not been as extensive as the data on smoking initiation. Although considerable effort has been invested in studies to assess therapeutic methods of achieving smoking cessation (Fiore et al. 2000), few longitudinal studies have examined predictors of continued smoking, attempts to stop smoking, short- or long-term cessation, or relapse to smoking among women who smoke regularly and are not enrolled in smoking cessation programs.

To assess studies of smoking maintenance and cessation, a general-purpose framework was used in the 1989 Surgeon General's report on the health consequences of smoking (USDHHS 1989, Chapter 5, Part II). The report discussed three general types of predictors of maintenance or cessation of smoking:

- 1.

pharmacologic processes and conditions, which are basic factors that interact to produce addiction and to support continued smoking (e.g., number of cigarettes smoked, number of previous attempts to stop smoking, and number of years of smoking);

- 2.

cognition and decision-making ability (e.g., knowledge about the effects of smoking on health, motivation to continue or to stop smoking, and confidence in one's ability to stop smoking); and

- 3.

personal characteristics and social context (personality, demographic factors, and environmental influences).

The "transtheoretical model" of Prochaska and colleagues (1992) posits a sequence of five stages in the process of smoking cessation: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance of cessation. This model, often referred to as the stages of change model, provides a template for evaluating willingness to change. It has been used in many studies of smoking cessation and as an adjunct to clinical and public health smoking cessation programs.

A major conclusion of the 1980 Surgeon General's report on the health consequences of smoking among women was that "Women at higher education and income levels are more likely to succeed in quitting" (USDHHS 1980, p. 347). The report also noted that successful smoking cessation is associated with a strong commitment to change, involvement in programs that use behavioral techniques, and social support for smoking cessation. These conclusions were based on information about persons who sought treatment to stop smoking; the conclusions revealed little about successful efforts by persons who did not seek treatment. Furthermore, the report recommended development of intervention strategies to target social norms and the particular needs and concerns among women, such as social support and weight gain. According to the report, the longitudinal data available were insufficient to address the factors that influence the cessation process among active smokers. Before 1980, only one longitudinal study of the psychosocial and behavioral aspects of smoking among women had been conducted (Cherry and Kiernan 1976).

Because most smokers, both women and men, stop smoking without formal cessation programs (Schwartz and Dubitzky 1967; Fiore et al. 1990; Yankelovich Partners 1998), understanding the factors that contribute to their attempts to stop smoking and their success in doing so would be helpful in the planning of public health efforts and smoking cessation programs. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs have been used to investigate factors related to changes in smoking status among adults who smoke regularly. Cross-sectional study designs have well-recognized limitations, most notably that the temporal relationship between smoking outcomes and predictor variables cannot be satisfactorily assessed (Flay et al. 1983; Chassin et al. 1986; Collins et al. 1987; Conrad et al. 1992). In contrast, even though longitudinal studies do not prove causation, they can be used to place potential predictors and outcomes in temporal sequence and, thus, to suggest possible cause-and-effect relationships (Conrad et al. 1992). Thousands of studies of smoking and its determinants have been conducted, but despite the plea of the Surgeon General's report in 1980, very few longitudinal studies have investigated factors related to changes in the smoking behavior among women who have not enrolled in cessation programs or who have not participated in laboratory studies.

This review includes longitudinal observational studies in which female smokers were surveyed and were followed up over time. Studies that provided results for female smokers and male smokers separately also were included in this review to examine differences in predictors of smoking status between females and males. Studies were excluded for one or more of the following reasons: (1) Results were based on data from smokers exposed to an intervention. (2) Results were based on cross-sectional data, even though the data were collected as part of a longitudinal study. (3) Data analyses did not examine factors related to smoking outcome, did not stratify by gender, or did not examine changes in smoking behavior over time. (4) The primary focus of the study was smoking initiation or transition to regular smoking among adolescents or adults who had previously stopped smoking. (5) The research addressed validity and feasibility of study designs, smoking prevalence, or effects on health rather than smoking maintenance and cessation.

With the use of these guidelines, only 13 studies were selected after review of 2,552 abstracts of research published between 1966 and May 1999; they are available in the MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Psychlit databases. One unpublished study was also identified through consultation with experts in the field of smoking and health.

Of the 13 studies of smoking maintenance or cessation reviewed here (Table 4.2), 6 included women only, and 7 included both women and men. Study populations ranged from children and adolescents who were followed up into young adulthood to persons aged 65 years or older at enrollment in the study. Four studies were part of national surveys, and 1 study focused on data from a registry of twins. Seven studies were conducted in the United States; the remaining 6 were performed in Denmark, England, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Most of the studies involved urban populations.

Table

Table 4.2. Characteristics of 13 longitudinal studies of smoking maintenance and cessation among women who smoked regularly.

Eight studies used self-administered questionnaires to determine smoking status; five used either telephone or household in-person interviews. Although retrospective data on smoking status during pregnancy were included in two studies, they are likely to be accurate. The information for one of these studies was obtained just two weeks after childbirth and information for the other at the time of delivery, with data on smoking during early pregnancy having been obtained by a nurse or physician at the first routine prenatal visit with a standardized form used in Norway. In two studies, biochemical validation of smoking cessation was performed. Several of the studies were not conducted explicitly to study smoking but included smoking in investigations of other health behaviors or outcomes, such as psychosocial factors affecting infant feeding practices. In the study by O'Campo and colleagues (1992), extensive information on smoking patterns was obtained because it was assumed to be relevant to breastfeeding, but attitudinal and cognitive factors related to smoking behavior were not goals of the study and, thus, were not examined.

Most of the 13 studies focused on a narrow group of predictor variables, which limited the conclusions that could be drawn about the interaction of female gender and other variables. Only two studies (Garvey et al. 1992; Rose et al. 1996) included variables from all three of the domains set forth in the 1989 Surgeon General's report (pharmacologic processes and conditions, cognition and decision-making ability, and personal characteristics and social context). The specific variables and populations in these two studies differed. In all 13 studies, logistic regression, discriminate analysis, or proportional hazard models were used to discriminate between regular smokers at baseline assessment who had stopped smoking by the time of follow-up and those who had not stopped smoking.

A range of criteria was used to define smoking status, and several studies did not clearly define or limit those criteria. For example, one study (Cnattingius et al. 1992) compared continuing smokers with those who had stopped smoking during pregnancy. However, the group of continuing smokers included both women who had stopped smoking and subsequently started again and those who had never stopped smoking during pregnancy. As a result, the differences between smokers and those who had stopped smoking may have been diluted. Only one study (Garvey et al. 1992) involved separate consideration of predictors of early relapse and late relapse to smoking. The time between the first and final follow-up visits ranged from approximately nine months to 15 years in the 13 studies, but changes in baseline characteristics were not taken into account in the presentation of follow-up results. Consequently, if a baseline factor such as depression was measured when a woman was 20 years old but changed over time, conclusions about its relationship to smoking status years later may have been incorrect.

The percentage of women who were regular smokers at the beginning of the studies and for whom complete data were available at two or more follow-up periods ranged from 50 to 98 percent. High attrition is particularly problematic because it is likely not to be random (Ockene et al. 1982).

Transitions from Regular Smoking

Attempts to Stop Smoking

In 1987, among those who have ever smoked, only 18.5 percent of men and 19.5 percent of women in the United States reported they had never tried to quit (USDHHS 1990). In 1998, an estimated 39.2 percent of current daily smokers had stopped smoking for at least a day during the preceding 12 months because they were trying to quit (CDC 2000). However, only a small percentage of persons who try to quit in any given year remain abstinent.

Rose and colleagues (1996) examined the natural history of smoking from adolescence to adulthood and evaluated predictors of attempts to stop smoking in the previous five years. The category "quit attempt" included two groups: those who had stopped smoking but started again within six months or fewer, and those who abstained for more than six months. The study participants, females and males in grades 6 through 12 in a midwestern county school system, were first surveyed during a three-year period (1980-1983) and again for follow-up periods in 1987 and 1994. The study assessed changes in smoking status as of 1994 among participants who were smokers in 1987. The primary focus was on cognitive factors (e.g., confidence, health beliefs and values, and motivations for smoking) and personal characteristics (e.g., demographics, f status and education, employment status, social role, and negative affect).

In analyses based on the combined data for females and males, Rose and colleagues (1996) determined that smokers who reported an attempt to stop smoking were more likely to be women, to be married, to have more social roles, and to use smoking to control negative affect. Smokers who reported an attempt to stop smoking also gave higher ratings to the value of health and the perceived likelihood of not smoking in one year than did those who had made no attempt to stop smoking. Female smokers with lower sensory motivation (e.g., less enjoyment in handling a cigarette) were more likely to have attempted to stop smoking, whereas the opposite was true among male smokers. The view that smoking has a negative effect on personal health was related to attempts to stop smoking among heavy smokers but not among light smokers.

Although females were more likely than males to attempt to stop smoking, no gender-specific differences were observed in the success of these attempts (Rose et al. 1996). Because study participants were of childbearing age, pregnancy may have increased the number of attempts among women to stop smoking. The number of cigarettes smoked daily did not affect attempts to stop smoking when other factors were controlled for, but it did affect the success of these attempts. In general, both females and males who attempt to stop smoking may be cognitively more ready to stop (i.e., have higher perceived likelihood of not smoking and higher perceived value of health) than do smokers who do not attempt to stop (Rose et al. 1996). These findings are difficult to generalize, however, because the study population was relatively well educated, white, young, and from the Midwest. In addition, some potentially relevant predictors among women (e.g., motives to control weight and spousal support) were not assessed.

Smoking Cessation

Because all 13 studies in this overview (Table 4.2) investigated predictors of smoking cessation, considering smoking cessation among young persons, pregnant women, young and middle-aged adults, and older adults separately is possible.

Young Persons

Two studies focused on smoking cessation among young persons (Cherry and Kiernan 1976; Rose et al. 1996). Cherry and Kiernan examined the relationship between personality scores and smoking behavior in a cohort of respondents to the National Survey of Health and Development, which was conducted in England. A geographically diverse sample of young persons was surveyed at age 16 years in 1962, age 20 years in 1966, and age 25 years in 1971. At baseline, participants completed the Maudsley Personality Inventory (Eysenck 1958), and information about smoking behavior was obtained at the follow-up intervals. By age 25 years, complete information on both cigarette smoking and personality was available for 2,753 of the 5,362 persons included in the baseline survey, excluding cigar and pipe smokers. The definition of smoking cessation did not specify a period of abstinence, but smokers who had "given up smoking" by age 25 years were considered "quitters" (Cherry and Kiernan 1976).

Variables studied by Cherry and Kiernan (1976) included some measures of pharmacologic and conditioning processes (e.g., age at smoking initiation, smoking rate, and degree of inhalation) as well as personal characteristics (e.g., personality traits of neuroticism or extroversion). Basic differences in personality traits were found among current smokers, former smokers, and nonsmokers. Separate assessments were made for females and males. Among both genders, smokers had higher scores for extroversion than did nonsmokers and former smokers had the highest mean score, but this score was not significantly higher than that among current smokers. Scores on the extroversion scale predicted smoking cessation by age 25 years, and extroverts were more likely than introverts to stop smoking. The number of cigarettes smoked also predicted smoking cessation by age 25 years; smokers who consumed fewer than 10 cigarettes per day were more likely to stop smoking. Higher scores for neuroticism predicted smoking cessation among males but not among females.

The study by Rose and colleagues (1996), described earlier, examined psychosocial predictors of attempts to stop smoking and of successful attempts. More females than males attempted to stop smoking, but gender was not related to successful smoking cessation. These findings differed from results of the cross-sectional component of the Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation. In that trial, investigators studied 3,553 adults (51 percent women) in 20 U.S. communities. They found that women were as likely as men to attempt to stop smoking but were less likely to remain abstinent (Royce et al. 1997).