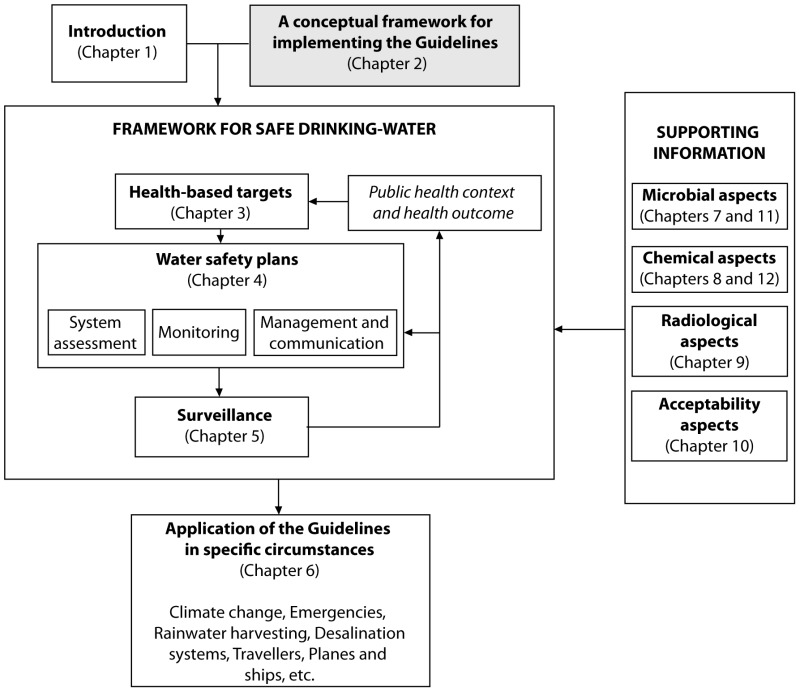

The basic and essential requirement to ensure the safety of drinking-water is the implementation of a “framework for safe drinking-water” based on the Guidelines. This framework provides a preventive, risk-based approach to managing water quality. It would be composed of health-based targets established by a competent health authority using the Guidelines as a starting point, adequate and properly managed systems (adequate infrastructure, proper monitoring and effective planning and management) and a system of independent surveillance. Such a framework would normally be enshrined in national standards, regulations, or guidelines, in conjunction with relevant policies and programmes (see sections 2.6 and 2.7). Resultant regulations and policies should be appropriate to local circumstances, taking into consideration environmental, social, economic and cultural issues and priority setting.

The framework for safe drinking-water is a preventive management approach comprising three key components:

a system assessment to determine whether the drinking-water supply (from source through treatment to the point of consumption) as a whole can deliver water of a quality that meets the health-based targets (

section 4.1);

operational monitoring of the control measures in the drinking-water supply that are of particular importance in securing drinking-water safety (

section 4.2);

management plans documenting the system assessment and monitoring plans and describing actions to be taken in normal operation and incident conditions, including upgrade and improvement, documentation and communication (

sections 4.4–

4.6);

a system of independent surveillance that verifies that the above are operating properly (

section 2.3 and

chapter 5).

Verification to determine whether the performance of the drinking-water supply is in compliance with the health-based targets and whether the WSP itself is effective may be undertaken by the supplier, surveillance agencies or a combination of the two (see section 4.3).

2.1. Health-based targets

Health-based targets are an essential component of the drinking-water safety framework. They should be established by a high-level authority responsible for health in consultation with others, including water suppliers and affected communities. They should take account of the overall public health situation and contribution of drinking-water quality to disease due to waterborne microbes and chemicals, as a part of overall water and health policy. They must also take account of the importance of ensuring access to water for all consumers.

Health-based targets provide the basis for the application of the Guidelines to all types of drinking-water suppliers. Some constituents of drinking-water may cause adverse health effects from single exposures (e.g. pathogenic microorganisms) or long-term exposures (e.g. many chemicals). Because of the range of constituents in water, their mode of action and the nature of fluctuations in their concentrations, there are four principal types of health-based targets used as a basis for identifying safety requirements:

Health outcome targets: Where waterborne disease contributes to a measurable and significant burden, reducing exposure through drinking-water has the potential to appreciably reduce the risks and incidence of disease. In such circumstances, it is possible to establish a health-based target in terms of a quantifiable reduction in the overall level of disease. This is most applicable where adverse effects follow shortly after exposure, where such effects are readily and reliably monitored and where changes in exposure can also be readily and reliably monitored. This type of health outcome target is primarily applicable to some microbial hazards in developing countries and chemical hazards with clearly defined health effects largely attributable to water (e.g. fluoride, nitrate/nitrite and arsenic). In other circumstances, health outcome targets may be the basis for evaluation of results through quantitative risk assessment models. In these cases, health outcomes are estimated based on information concerning high-dose exposure and dose–response relationships. The results may be employed directly as a basis for the specification of water quality targets or provide the basis for development of the other types of health-based targets. Health outcome targets based on information on the impact of tested interventions on the health of real populations are ideal, but rarely available. More common are health outcome targets based on defined levels of tolerable risk, either absolute or fractions of total disease burden, usually based on toxicological studies in experimental animals and occasionally based on epidemiological evidence.

Water quality targets: Water quality targets are established for individual drinking-water constituents that represent a health risk from long-term exposure and where fluctuations in concentration are small. They are typically expressed as guideline values (concentrations) of the substances or chemicals of concern.

Performance targets: Performance targets are employed for constituents where short-term exposure represents a public health risk or where large fluctuations in numbers or concentration can occur over short periods with significant health implications. These are typically technology based and expressed in terms of required reductions of the substance of concern or effectiveness in preventing contamination.

Specified technology targets: National regulatory agencies may establish other recommendations for specific actions for smaller municipal, community and household drinking-water supplies. Such targets may identify specific permissible devices or processes for given situations and/or for generic drinking-water system types.

It is important that health-based targets are realistic under local operating conditions and are set to protect and improve public health. Health-based targets underpin the development of WSPs, provide information with which to evaluate the adequacy of existing installations and assist in identifying the level and type of inspection and analytical verifications that are appropriate.

Most countries apply several types of targets for different types of supplies and different contaminants. In order to ensure that they are relevant and supportive, representative scenarios should be developed, including description of assumptions, management options, control measures and indicator systems for performance tracking and verification, where appropriate. These should be supported by general guidance addressing the identification of national, regional or local priorities and progressive implementation, thereby helping to ensure that best use is made of limited resources.

Health-based targets are considered in more detail in chapter 3.

For guidance on how to prioritize constituents based on greatest risk to public health, the reader should refer to section 2.5 and the supporting document Chemical safety of drinking-water (Annex 1).

2.2. Water safety plans

Overall control of the microbial and chemical quality of drinking-water requires the development of management plans that, when implemented, provide the basis for system protection and process control to ensure that numbers of pathogens and concentrations of chemicals present a negligible risk to public health and that water is acceptable to consumers. The management plans developed by water suppliers are WSPs. A WSP comprises system assessment and design, operational monitoring and management plans, including documentation and communication. The elements of a WSP build on the multiple-barrier principle, the principles of hazard analysis and critical control points and other systematic management approaches. The plans should address all aspects of the drinking-water supply and focus on the control of abstraction, treatment and delivery of drinking-water.

Many drinking-water supplies provide adequate safe drinking-water in the absence of formalized WSPs. Major benefits of developing and implementing a WSP for these supplies include the systematic and detailed assessment and prioritization of hazards, the operational monitoring of barriers or control measures and improved documentation. In addition, a WSP provides for an organized and structured system to minimize the chance of failure through oversight or lapse of management and for contingency plans to respond to system failures or unforeseen events that may have an impact on water quality, such as increasing severe droughts, heavy rainfall or flood events.

2.2.1. System assessment and design

Assessment of the drinking-water system is applicable, with suitable modifications, to large utilities with piped distribution systems, piped and non-piped community supplies, including hand pumps, and individual domestic supplies, including rainwater. The complexity of a WSP varies with the circumstances. Assessment can be of existing infrastructure or of plans for new supplies or for upgrading existing supplies. As drinking-water quality varies throughout the system, the assessment should aim to determine whether the final quality of water delivered to the consumer will routinely meet established health-based targets. Understanding source quality and changes throughout the system requires expert input. The assessment of systems should be reviewed periodically.

The system assessment needs to take into consideration the behaviour of selected constituents or groups of constituents that may influence water quality. After actual and potential hazards, including events and scenarios that may affect water quality, have been identified and documented, the level of risk for each hazard can be estimated and ranked, based on the likelihood and severity of the consequences.

Validation is an element of system assessment. It is undertaken to ensure that the information supporting the plan is correct and is concerned with the assessment of the scientific and technical inputs into the WSP. Evidence to support the WSP can come from a wide variety of sources, including scientific literature, regulation and legislation departments, historical data, professional bodies and supplier knowledge.

The WSP is the management tool that should be used to assist in actually meeting the health-based targets, and it should be developed following the steps outlined in chapter 4. If the system is unlikely to be capable of meeting the health-based targets, a programme of upgrading (which may include capital investment or training) should be initiated to ensure that the drinking-water supply would meet the targets. The WSP is an important tool in identifying deficiencies and where improvements are most needed. In the interim, the WSP should be used to assist in making every effort to supply water of the highest achievable quality. Where a significant risk to public health exists, additional measures may be appropriate, including notification, information on compensatory options (e.g. boiling or disinfection at the point of use) and availability of alternative and emergency supplies when necessary.

System assessment and design are considered in more detail in section 4.1 (see also the supporting document Upgrading water treatment plants; Annex 1).

2.2.2. Operational monitoring

Operational monitoring is the conduct of planned observations or measurements to assess whether the control measures in a drinking-water system are operating properly. It is possible to set limits for control measures, monitor those limits and take corrective action in response to a detected deviation before the water becomes unsafe. Operational monitoring would include actions, for example, to rapidly and regularly assess whether the structure around a hand pump is complete and undamaged, the turbidity of water following filtration is below a certain value or the chlorine residual after disinfection plants or at the far point of the distribution system is above an agreed value.

Operational monitoring is usually carried out through simple observations and tests, in order to rapidly confirm that control measures are continuing to work. Control measures are actions implemented in the drinking-water system that prevent, reduce or eliminate contamination and are identified in system assessment. They include, for example, management actions related to the catchment, the immediate area around a well, filters and disinfection infrastructure and piped distribution systems. If collectively operating properly, they would ensure that health-based targets are met.

The frequency of operational monitoring varies with the nature of the control measure—for example, checking structural integrity monthly to yearly, monitoring turbidity online or very frequently and monitoring disinfectant residual at multiple points daily or continuously online. If monitoring shows that a limit does not meet specifications, then there is the potential for water to be, or to become, unsafe. The objective is timely monitoring of control measures, with a logically based sampling plan, to prevent the delivery of potentially unsafe water.

Operational monitoring includes observing or testing parameters such as turbidity, chlorine residual or structural integrity. More complex or costly microbial or chemical tests are generally applied as part of validation and verification activities (discussed in sections 4.1.7 and 4.3, respectively) rather than as part of operational monitoring.

In order not only to have confidence that the chain of supply is operating properly, but to confirm that safe water quality is being achieved and maintained, it is necessary to carry out verification, as outlined in section 4.3.

The use of indicator organisms (see section 11.6) in the monitoring of water quality is discussed in the supporting document Assessing microbial safety of drinking water (see Annex 1), and operational monitoring is considered in more detail in section 4.2.

2.2.3. Management plans, documentation and communication

A management plan documents system assessment and operational monitoring and verification plans and describes actions in both normal operation and during “incidents” where a loss of control of the system may occur. The management plan should also outline procedures and other supporting programmes required to ensure optimal operation of the drinking-water system.

As the management of some aspects of the drinking-water system often falls outside the responsibility of a single agency it is essential that the roles, accountabilities and responsibilities of the various agencies involved be defined in order to coordinate their planning and management. Appropriate mechanisms and documentation should therefore be established for ensuring stakeholder involvement and commitment. This may include establishing working groups, committees or task forces, with appropriate representatives, and developing partnership agreements, including, for example, signed memoranda of understanding (see also section 1.2).

Documentation of all aspects of drinking-water quality management is essential. Documents should describe activities that are undertaken and how procedures are performed. They should also include detailed information on:

assessment of the drinking-water system (including flow diagrams and potential hazards);

control measures and operational monitoring and verification plans and performance consistency;

routine operation and management procedures;

incident and emergency response plans;

supporting measures, including:

- —

training programmes;

- —

research and development;

- —

procedures for evaluating results and reporting;

- —

performance evaluations, audits and reviews;

- —

communication protocols;

community consultation.

Documentation and record systems should be kept as simple and focused as possible. The level of detail in the documentation of procedures should be sufficient to provide assurance of operational control when coupled with suitably qualified and competent operators.

Mechanisms should be established to periodically review and, where necessary, revise documents to reflect changing circumstances. Documents should be assembled in a manner that will enable any necessary modifications to be made easily. A document control system should be developed to ensure that current versions are in use and obsolete documents are discarded.

Appropriate documentation and reporting of incidents or emergencies should also be established. The organization should learn as much as possible from an incident to improve preparedness and planning for future events. Review of an incident may indicate necessary amendments to existing protocols.

Effective communication to increase community awareness and knowledge of drinking-water quality issues and the various areas of responsibility helps consumers to understand and contribute to decisions about the service provided by a drinking-water supplier or land use constraints imposed in catchment areas. It can encourage the willingness of consumers to generate funds to finance needed improvements. A thorough understanding of the diversity of views held by individuals or groups in the community is necessary to satisfy community expectations.

Management, documentation and communication are considered in more detail in sections 4.4, 4.5 and 4.6.

2.3. Surveillance

Surveillance agencies are responsible for an independent (external) and periodic review of all aspects of quality and public health safety and should have the power to investigate and to compel action to respond to and rectify incidents of contamination-caused outbreaks of waterborne disease or other threats to public health. The act of surveillance includes identifying potential drinking-water contamination and waterborne illness events and, more proactively, assessing compliance with WSPs and promoting improvement of the quality, quantity, accessibility, coverage, affordability and continuity of drinking-water supplies.

Surveillance of drinking-water requires a systematic programme of data collection and surveys that may include auditing of WSPs, analysis, sanitary inspection and institutional and community aspects. It should cover the whole of the drinking-water system, including sources and activities in the catchment, transmission infrastructure, whether piped or unpiped, treatment plants, storage reservoirs and distribution systems.

As incremental improvement and prioritizing action in systems presenting greatest overall risk to public health are important, there are advantages to adopting a grading scheme for the relative safety of drinking-water supplies (see chapter 4). More sophisticated grading schemes may be of particular use in community supplies where the frequency of testing is low and exclusive reliance on analytical results is particularly inappropriate. Such schemes will typically take account of both analytical findings and sanitary inspection through approaches such as those presented in section 4.1.2.

The role of surveillance is discussed in section 1.2.1 and chapter 5.

2.4. Verification of drinking-water quality

Drinking-water safety is secured by application of a WSP, which includes monitoring the efficiency of control measures using appropriately selected determinants. In addition to this operational monitoring, a final verification of quality is required.

Verification is the use of methods, procedures or tests in addition to those used in operational monitoring to determine whether the performance of the drinking-water supply is in compliance with the stated objectives outlined by the health-based targets and whether the WSP needs modification or revalidation.

Verification of drinking-water may be undertaken by the supplier, surveillance agencies or a combination of the two (see section 4.3). Although verification is most commonly carried out by the surveillance agency, a utility-led verification programme can provide an additional level of confidence, supplementing regulations that specify monitoring parameters and frequencies.

2.4.1. Microbial water quality

For microbial water quality, verification is likely to be based on the analysis of faecal indicator microorganisms, with the organism of choice being Escherichia coli or, alternatively, thermotolerant coliforms (see sections 4.3.1, 7.4 and 11.6). Monitoring of specific pathogens may be included on very limited occasions to verify that an outbreak was waterborne or that a WSP has been effective. Escherichia coli provides conclusive evidence of recent faecal pollution and should not be present in drinking-water. Under certain circumstances, additional indicators, such as bacteriophages or bacterial spores, may be used.

However, water quality can vary rapidly, and all systems are at risk of occasional failure. For example, rainfall can greatly increase the levels of microbial contamination in source waters, and waterborne outbreaks often occur following rainfall. Results of analytical testing must be interpreted taking this into account.

2.4.2. Chemical water quality

Assessment of the adequacy of the chemical quality of drinking-water relies on comparison of the results of water quality analysis with guideline values. These Guidelines provide guideline values for many more chemical contaminants than will actually affect any particular water supply, so judicious choices for monitoring and surveillance should be made prior to initiating an analytical chemical assessment.

For additives (i.e. chemicals deriving primarily from materials and chemicals used in the production and distribution of drinking-water), emphasis is placed on the direct control of the quality of these commercial products. In controlling drinking-water additives, testing procedures typically assess whether the product meets the specifications (see section 8.5.4).

As indicated in chapter 1, most chemicals are of concern only following long-term exposure; however, some hazardous chemicals that occur in drinking-water are of concern because of effects arising from sequences of exposures over a short period. Where the concentration of the chemical of interest (e.g. nitrate/nitrite, which is associated with methaemoglobinaemia in bottle-fed infants) varies widely, even a series of analytical results may fail to fully identify and describe the public health risk. In controlling such hazards, attention must be given to both knowledge of causal factors such as fertilizer use in agriculture and trends in detected concentrations, as these will indicate whether a significant problem may arise in the future. Other hazards may arise intermittently, often associated with seasonal activity or seasonal conditions. One example is the occurrence of blooms of toxic cyanobacteria in surface water.

A guideline value represents the concentration of a constituent that does not exceed tolerable risk to the health of the consumer over a lifetime of consumption. Guideline values for some chemical contaminants (e.g. lead, nitrate) are set to be protective for susceptible subpopulations. These guideline values are also protective of the general population over a lifetime.

It is important that recommended guideline values are scientifically justified, practical and feasible to implement as well as protective of public health. Guideline values are not normally set at concentrations lower than the detection limits achievable under routine laboratory operating conditions. Moreover, some guideline values are established taking into account available techniques for controlling, removing or reducing the concentration of the contaminant to the desired level. In some instances, therefore, provisional guideline values have been set for contaminants for which calculated health-based values are not practically achievable.

2.5. Identifying priority concerns

These Guidelines cover a large number of potential constituents in drinking-water in order to meet the varied needs of countries worldwide. Generally, however, only a few constituents will be of public health concern under any given circumstances. It is essential that the national regulatory agency and local water authorities identify and respond to the constituents of relevance to the local circumstances. This will ensure that efforts and investments can be directed to those constituents that have the greatest risk or public health significance.

Health-based targets are established for potentially hazardous water constituents and provide a basis for assessing drinking-water quality. Different parameters may require different priorities for management to improve and protect public health. In general, the priorities, in decreasing order, are to:

ensure an adequate supply of microbially safe water and maintain acceptability to discourage consumers from using potentially less microbially safe water;

manage key chemical hazards known to cause adverse health effects;

address other chemical hazards, particularly those that affect the acceptability of drinking-water in terms of its taste, odour and appearance;

apply appropriate technologies to reduce contaminant concentrations in the source to below the guideline or regulated values.

The two key features in choosing hazards for which setting a standard is desirable on health grounds are the health impacts (severity) associated with the substance and the probability of significant occurrence (exposure). Combined, these elements determine the risk associated with a particular hazard. For microbial hazards, the setting of targets will be influenced by occurrence and concentrations in source waters and the relative contribution of waterborne organisms to disease. For chemical hazards, the factors to be considered are the severity of health effects and the frequency of exposure of the population in combination with the concentration to which they will be exposed. The probability of health effects clearly depends on the toxicity and the concentration, but it also depends on the period of exposure. For most chemicals, health impacts are associated with long-term exposure. Hence, in the event that exposure is occasional, the risk of an adverse health effect is likely to be low, unless the concentration is extremely high. The substances of highest priority will therefore be those that occur widely, are present in drinking-water sources or drinking-water all or most of the time and are present at concentrations that are of health concern.

Many microbial and chemical constituents of drinking-water can potentially cause adverse human health effects. The detection of these constituents in both raw water and water delivered to consumers is often slow, complex and costly, which limits early warning capability and affordability. Reliance on water quality determination alone is insufficient to protect public health. As it is neither physically nor economically feasible to test for all drinking-water quality parameters, the use of monitoring effort and resources should be carefully planned and directed at significant or key characteristics.

Guidance on determining which chemicals are of importance in a particular situation is given in the supporting document Chemical safety of drinking-water (Annex 1).

Although WHO does not set formal guideline values for substances on the basis of consumer acceptability (i.e. substances that affect the appearance, taste or odour of drinking-water), it is not uncommon for standards to be set for substances and parameters that relate to consumer acceptability. Although exceeding such a standard is not a direct issue for health, it may be of great significance for consumer confidence and may lead consumers to obtain their water from an alternative, less safe source. Such standards are usually based on local considerations of acceptability.

Priority setting should be undertaken on the basis of a systematic assessment based on collaborative effort among all relevant agencies and may be applied at national and system-specific levels. At the national level, priorities need to be set in order to identify the relevant hazards, based on an assessment of risk—i.e. severity and exposure. At the level of individual water supplies, it may be necessary to also prioritize constituents for effective system management. These processes may require the input of a broad range of stakeholders, including health, water resources, drinking-water supply, environment, agriculture and geological services/mining authorities, to establish a mechanism for sharing information and reaching consensus on drinking-water quality issues.

2.5.1. Undertaking a drinking-water quality assessment

In order to determine which constituents are, indeed, of concern, it will be necessary to undertake a drinking-water quality assessment. It is important to identify what types of drinking-water systems are in place in the country (e.g. piped water supplies, non-piped water supplies, vended water) and the quality of drinking-water sources and supplies.

Additional information that should be considered in the assessment includes catchment type (protected, unprotected), wastewater discharges, geology, topography, agricultural land use, industrial activities, sanitary surveys, records of previous monitoring, inspections and local and community knowledge. The wider the range of data sources used, the more useful the results of the process will be.

In many situations, authorities or consumers may have already identified a number of drinking-water quality problems, particularly where they cause obvious health effects or acceptability problems. These existing problems would normally be assigned a high priority.

Drinking-water supplies that represent the greatest risks to public health should be identified, with resources allocated accordingly.

2.5.2. Assessing microbial priorities

The most common and widespread health risk associated with drinking-water is microbial contamination, the consequences of which mean that its control must always be of paramount importance. Priority needs to be given to improving and developing the drinking-water supplies that represent the greatest public health risk.

The most common and widespread health risk associated with drinking-water is microbial contamination, the consequences of which mean that its control must always be of paramount importance.

Health-based targets for microbial contaminants are discussed in section 3.2, and a comprehensive consideration of microbial aspects of drinking-water quality is contained in chapter 7.

2.5.3. Assessing chemical priorities

Not all of the chemicals with guideline values will be present in all water supplies or, indeed, all countries. If they do exist, they may not be found at levels of concern. Conversely, some chemicals without guideline values or not addressed in the Guidelines may nevertheless be of legitimate local concern under special circumstances.

Risk management strategies (as reflected in national standards and monitoring activities) and commitment of resources should give priority to those chemicals that pose a risk to human health or to those with significant impacts on the acceptability of water.

Only a few chemicals have been shown to cause widespread health effects in humans as a consequence of exposure through drinking-water when they are present in excessive quantities. These include fluoride, arsenic and nitrate. Human health effects associated with lead (from domestic plumbing) have also been demonstrated in some areas, and there is concern because of the potential extent of exposure to selenium and uranium in some areas at concentrations of human health significance. Iron and manganese are of widespread significance because of their effects on acceptability. These constituents should be taken into consideration as part of any priority-setting process. In some cases, assessment will indicate that no risk of significant exposure exists at the national, regional or system level.

Drinking-water may be only a minor contributor to the overall exposure to a particular chemical, and in some circumstances controlling the levels in drinking-water, at potentially considerable expense, may have little impact on overall exposure. Drinking-water risk management strategies should therefore be considered in conjunction with other potential sources of human exposure.

The process of “short-listing” chemicals of concern may initially be a simple classification of high and low risk to identify broad issues. This may be refined using data from more detailed assessments and analysis and may take into consideration rare events, variability and uncertainty.

Guidance on how to undertake prioritization of chemicals in drinking-water is provided in the supporting document Chemical safety of drinking-water (Annex 1). This deals with issues including:

the probability of exposure (including the period of exposure) of the consumer to the chemical;

the concentration of the chemical that is likely to give rise to health effects (see also

section 8.5);

the evidence of health effects or exposure arising through drinking-water, as opposed to other sources, and relative ease of control of the different sources of exposure.

Additional information on the hazards and risks of many chemicals not included in these Guidelines is available from several sources, including WHO Environmental Health Criteria monographs and Concise International Chemical Assessment Documents, reports by the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues and the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives and information from competent national authorities. These information sources have been peer reviewed and provide readily accessible information on toxicology, hazards and risks of many less common contaminants. They can help water suppliers and health officials to decide upon the significance (if any) of a detected chemical and on the response that might be appropriate.

2.6. Developing drinking-water quality standards

Health-based targets, including numeric guideline values and other targets described in the Guidelines for drinking-water quality, are not intended to be mandatory limits, but are provided as the scientific point of departure for development of national or regional numerical drinking-water quality standards. No single approach is universally applicable, and the nature and form of drinking-water standards may vary among countries and regions.

In developing national drinking-water standards based on these Guidelines, it will be necessary to take account of a variety of environmental, social, cultural, economic, dietary and other conditions affecting potential exposure. This may lead to national standards that differ appreciably from these Guidelines, both in scope as well as in risk targets. A programme based on modest but realistic goals—including fewer water quality parameters of priority health concern at attainable levels consistent with providing a reasonable degree of public health protection in terms of reduction of disease or disease risk within the population—may achieve more than an overambitious one, especially if targets are upgraded periodically.

To ensure that standards are acceptable to consumers, communities served, together with the major water users, should be involved in the standards-setting process. Public health agencies may be closer to the community than those responsible for its drinking-water supply. At a local level, they also interact with other sectors (e.g. education), and their combined action is essential to ensure active community involvement.

2.6.1. Adapting guideline values to locally relevant standards

In order to account for variations in exposure from different sources (e.g. water, food) in different parts of the world, the proportion of the tolerable daily intake allocated to drinking-water in setting guideline values for many chemicals will vary. Where relevant exposure data are available, authorities are encouraged to develop context-specific guideline values that are tailored to local circumstances and conditions. For example, in areas where the intake of a particular contaminant in drinking-water is known to be much greater than that from other sources (e.g. air and food), it may be appropriate to allocate a greater proportion of the tolerable daily intake to drinking-water to derive a guideline value more suited to the local conditions.

Daily water intake can vary significantly in different parts of the world, seasonally and particularly where consumers are involved in manual labour in hot climates. Local adjustments to the daily water consumption value may be needed in setting local standards, as in the case of fluoride, for example.

Volatile substances in water may be released into the air during showering and through a range of other household activities. Under such circumstances, inhalation may become a significant route of exposure. Where such exposure is shown to be important for a particular substance (i.e. high volatility, low ventilation rates and high rates of showering/bathing), it may be appropriate to adjust the guideline value. For those substances that are particularly volatile, such as chloroform, the correction factor would be approximately equivalent to a doubling of exposure. For further details, the reader should refer to section 8.2.9.

2.6.2. Periodic review and revision of standards

As knowledge increases, there may be changes to specific guideline values or consideration of new hazards for the safety of drinking-water. There will also be changes in the technology of drinking-water treatment and analytical methods for contaminants. National or subnational standards must therefore be subjected to periodic review and should be structured in such a way that changes can be made readily. Changes may need to be made to modify standards, remove parameters or add new parameters, but no changes should be made without proper justification through risk assessment and prioritization of resources for protecting public health. Where changes are justified, it is important that they are communicated to all stakeholders.

2.7. Drinking-water regulations and supporting policies and programmes

The incorporation of a preventive risk management and prioritization approach to drinking-water quality regulations, policies and programmes will:

ensure that regulations support the prioritization of drinking-water quality parameters to be tested, instead of making mandatory the testing of every parameter in these Guidelines;

ensure implementation of appropriate sanitation measures at community and household levels and encourage action to prevent or mitigate contamination at source;

identify drinking-water supplies that represent the greatest risks to public health and thus determine the appropriate allocation of resources.

2.7.1. Regulations

The alignment of national drinking-water quality regulations with the principles outlined in these Guidelines will ensure that:

there is an explicit link between drinking-water quality regulations and the protection of public health;

regulations are designed to ensure safe drinking-water from source to consumer, using multiple barriers;

regulations are based on good practices that have been proven to be appropriate and effective over time;

a variety of tools are in place to build and ensure compliance with regulations, including education and training programmes, incentives to encourage good practices and penalties, if enforcement is required;

regulations are appropriate and realistic within national, subnational and local contexts, including specific provisions or approaches for certain contexts or types of supplies, such as small community water supplies;

stakeholder roles and responsibilities, including how they should work together, are clearly defined;

“what, when and how” information is shared between stakeholders—including consumers—and required action is clearly defined for normal operations and in response to incidents or emergencies;

regulations are adaptable to reflect changes in contexts, understanding and technological innovation and are periodically reviewed and updated;

regulations are supported by appropriate policies and programmes.

The aim of drinking-water quality regulations should be to ensure that the consumer has access to sustainable, sufficient and safe drinking-water. Enabling legislation should provide broad powers and scope to related regulations and include public health protection objectives, such as the prevention of waterborne disease and the provision of an adequate supply of drinking-water. Drinking-water regulations should focus on improvements to the provision and safety of drinking-water through a variety of requirements, tools and compliance strategies. Although sanctions are needed within regulations, the principal aim is not to shut down deficient water supplies.

Drinking-water quality regulations are not the only mechanism by which public health can be protected. Other regulatory mechanisms include those related to source water protection, infrastructure, water treatment and delivery, surveillance and response to potential contamination and waterborne illness events.

Drinking-water quality regulations may also provide for interim standards, permitted deviations and exemptions as part of a national or regional policy, rather than as a result of local initiatives. This may take the form of temporary exemptions for certain communities or areas for defined periods of time. Short-term and medium-term targets should be set so that the most significant risks to human health are managed first. Regulatory frameworks should support long-term progressive improvements.

2.7.2. Supporting policies and programmes

Developing and promulgating regulations alone will not ensure that public health is protected. Regulations must be supported by adequate policies and programmes. This includes ensuring that regulatory authorities, such as enforcement agencies, have sufficient resources to fulfil their responsibilities and that the appropriate policy and programme supports are in place to assist those required to comply with regulations. In other words, the appropriate supports need to be in place so that those being regulated and those who are responsible for regulating are not destined to fail.

Implementation or modification of policies and programmes to provide safe drinking-water should not be delayed because of a lack of appropriate regulation. Even where drinking-water regulations do not yet exist, it may be possible to encourage, and even enforce, the supply of safe drinking-water through, for example, educational efforts or commercial, contractual arrangements between consumer and supplier (e.g. based on civil law).

In countries where universal access to safe drinking-water at an acceptable level of service has not been achieved, policies should refer to expressed targets for increases in sustainable access to safe drinking-water. Such policy statements should be consistent with achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/) of the United Nations Millennium Declaration and should take account of levels of acceptable access outlined in General Comment 15 on the Right to Water of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (http://umn.edu/humanrts/gencomm/escgencom15.htm) and associated documents.