NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Using Technology-Based Therapeutic Tools in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2015. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 60.)

Using Technology-Based Therapeutic Tools in Behavioral Health Services.

Show detailsIntroduction

In this chapter, you will meet several counselors who provide technology-assisted care (TAC) to clients who have mental or substance use disorders in various settings, including a student counseling center in a community college; an inpatient co-occurring disorders (CODs) unit in a large city; an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) team at a community mental health center's (CMHC's) day hospital program; a pretreatment group in a rural area; a community behavioral health agency in a small city; and a CMHC that serves several counties. Each vignette begins by describing the setting, learning objectives, strategies and techniques, and counselor skills and attitudes specific to that vignette. Then a description of the client's situation and current symptoms is given. Each vignette provides counselor-client dialog to facilitate learning, along with:

- Master clinician notes: comments from the point of view of an experienced clinician about the strategies used, possible alternative techniques, and insights into what the client or prospective client may be thinking.

- How-to boxes: step-by-step information on how to implement a specific intervention.

The master clinician represents the combined experience of the contributors to this Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). Master clinician notes assist behavioral health counselors at all levels: beginners, those with some experience, and veteran practitioners. Before using the described techniques, it is your responsibility to determine if you have sufficient training in the skills required to use the techniques and to ensure that you are practicing within the legal and ethical bounds of your training, certifications, and licenses. It is always helpful to obtain clinical supervision in developing or enhancing clinical skills. For additional information on clinical supervision, see TIP 52, Clinical Supervision and the Professional Development of the Substance Abuse Counselor (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009b). As you are reading, try to imagine yourself throughout the course of each vignette in the role of the counselor. This chapter presents five vignettes, which can be briefly summarized as follows.

Vignette 1: Implementing a Web-Based Prevention, Outreach, and Early Intervention Program for Young Adults. This vignette discusses administrative issues in developing and implementing a Web-based prevention and intervention program and then demonstrates the capability of such a program to meet the stress management needs of a college student.

Vignette 2: Using Computerized Check-In and Monitoring in an Extended Recovery Program. This vignette demonstrates how computerized check-in and monitoring can support recovery for clients with co-occurring substance use disorders and serious mental illness (SMI).

Vignette 3: Conducting a Telephone- and Videoconference-Based Pretreatment Group for Clients With Substance Use Disorders. This vignette demonstrates how to serve clients in a rural area who are on a wait list for treatment by providing a pretreatment group conducted using video and telephone conferencing.

Vignette 4: Incorporating TAC Into Behavioral Health Services for Clients Who Are Hearing Impaired. This vignette describes ways in which TAC can support intake, assessment, referral, treatment, and continuing care for clients who are hearing impaired, a specific group of people for whom technology plays a particularly important role in access to care. Deaf clients and others in the Deaf community may prefer the term “Deaf” over “hearing impaired,” and you should adjust the terminology you use accordingly.

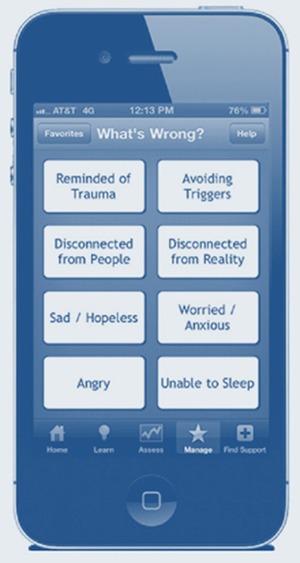

Vignette 5: Using Smartphones To Support Recovery for Clients With CODs. This vignette illustrates how mobile phone applications (apps) can be used to help clients with mental illness regulate their emotional responses, enhance the therapeutic alliance (between the client and counselor), and engage in effective coping strategies.

Vignette 1. Implementing a Web-Based Prevention, Outreach, and Early Intervention Program for Young Adults

Overview

This vignette introduces a prevention, outreach, and early intervention program that young adults can access via portable devices, such as smartphones and tablets, as well as via desktop computers. The program delivers intervention content through engaging technologies, including audio, video, text, and other interactive tools. It offers personalized assessments for alcohol, drug, and tobacco use; sexual health and sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention; stress; nutrition; and other issues young adults may face. The program also offers psychoeducation, goal setting, action planning, cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT), and skill-building tools. Programs like this one are packaged primarily for colleges and universities, but they can be customized to meet the needs of any population. This vignette first discusses some of the administrative issues in developing and implementing a Web-based prevention and intervention program; the second part of the vignette demonstrates the capability of such a program to meet the stress management needs of a college student. It then shows how the program might supplement early intervention efforts with an individual who is receiving counseling for a substance use disorder.

Learning Objectives

- Understand how to incorporate online screening tools into a larger program of prevention, screening, and early intervention for behavioral health difficulties.

- Identify individuals who need assistance and support by using an online screening tool for stress management.

- Use computer-assisted technologies to supplement ongoing counseling efforts and to extend traditional treatment services by providing support, education, and specific interventions.

- Become aware of issues that can arise when applying a technologically enriched, broad-based prevention and early intervention program with a specific target population.

- Evaluate the cost effectiveness of prevention and early intervention programs that include computer-assisted technologies.

Setting

John is a counselor in a local behavioral health center; his responsibilities include coordinating mental health and substance use disorder outreach and treatment services for students at the local community college. John and his two colleagues are seeing a significant increase in the number of stress-related requests for services from the student population. His center's resources are limited, so John has begun investigating online, client-driven tools that can be used with college-aged students in hopes of integrating such tools into his center's services. Students can access these resources from their computers or mobile devices. He hopes to be able to identify and appropriately serve three groups of people who may use behavioral health services: those with situational stress reactions, those who are experiencing significant stress and are at risk of more serious problems, and those who need acute care for pressing mental and/or substance use disorders.

In Part 1 of John's story, he searches for appropriate tools and meets with his program director to explore program development and implementation issues. In Part 2, John meets with Amy, a student experiencing significant stress, and helps her use the stress management component of the program to be able to continue in school and manage her school work. In Part 3, a student uses the program as an adjunct to counseling and mutual-help programs to address his drinking problem.

John's Story

Part 1. Providing targeted services

John, a senior counselor and college outreach coordinator for a local behavioral health center, is meeting with his program director, Nancy, to discuss how to provide better and more targeted services to students at the local college.

JOHN: I'm pulling my hair out with all these students coming in. I don't know why they're coming now. Maybe it's because it's the end of the semester, or maybe students have only just now begun to understand how they can benefit from help. We've just had an onslaught—more than we can really handle.

NANCY: What are the numbers?

JOHN: As you know, just three of us are handling this community college contract, and we've had 10 to 12 new students a week. They're coming in for stress-related issues and substance use. Alcohol problems are on the rise, and we're also seeing a lot more students smoking marijuana. Some of these kids are really under a huge amount of stress, but then again, I don't think others really need intensive services.

NANCY: So what are you thinking would be the best way to handle this increase?

JOHN: Well, I've done a little research, and I found some online resources that look pretty good. One is a comprehensive package for stress management, alcohol and drug use, nutrition, sexual health, and a variety of other topics. In this particular program, the students can go to the program Web site on their own, using a desktop computer, a laptop, a tablet, or even a smartphone. The site does some neat stuff based on education and CBT. There are a lot of cool tools that mirror things we already do clinically with students regarding prevention and relaxation. I wanted to talk with you about maybe integrating the package into our system of care.

NANCY: Do you know of any other college that's using this kind of program?

JOHN: Well, I don't have much spare time, you know? But I did some homework, and it seems like a number of colleges use this particular program. Some of them resemble our college, with an urban location, lots of commuting students, and limited treatment services for substance use and mental disorders. Some require all freshmen to do an orientation to the Web site, but others require that all students participate in just the alcohol and drug use part of the program. It looks like there are some data about the results and some evidence to support its use. I think it's pretty credible. What I like is that it's all contained in one package—just one stop and you'd have a range of resources to meet the variety of significant needs here in the college community.

NANCY: Can we get references from some of these other schools? I'd like to talk to them first. Also, I'm a little concerned about the all-inclusive package; it might be the case that not all elements of the package are high quality. We'll need to check into that.

JOHN: That's a good idea. I'll contact the colleges and talk to some of our colleagues there. I'll ask them about their experience with the program.

NANCY: I'd like to know whether there are other programs or other kinds of options. We could find out what the advantages or disadvantages are with them. I'd also be interested in how they measure success, and if we would measure it in the same way.

Master Clinician Note: Not everything that sounds good is good! Behavioral health service providers and program administrators must always ask questions and critically examine the evidence to determine whether a particular technology works or does what it purports to do. The National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (NREPP) may have helped John and Nancy find some clarity as they struggled with these concerns. NREPP is supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and reviews programs and services that voluntarily seek such review. The NREPP Web site offers information and assistance related to identifying and assessing the evidence-based qualifications of any program (http://nrepp.samhsa.gov). John and Nancy could also decide to collect information about the results of whatever program they decide to use; doing so could help them determine how well the program is working with their population.

Other helpful Web sites include:

http://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/NIAAACollegeMaterials/Default.aspx

http://www2.edc.org/cchs/projects.html

http://www.dartblog.com/images/NH%20Alcohol%20Best%20Practices.pdf

JOHN: There are similar tools online that help kids handle stress better and improve their time management abilities, and some have risk reduction programs attached to their substance use packages.

NANCY: I think we'd be better off using what has been tested on other campuses with a similar group of people who have similar problems. Of course, there may also be some new, relatively untested programs that look good too.

JOHN: That makes sense.

NANCY: On the other hand, I know there is a lot of stuff out there already, some of it pretty well documented. I wonder if we can make up our own package, from scratch, to reduce costs.

Characteristics of Digital Comprehensive Assessment Tools

- Use of digital tools saves time and cost; it can also free up clinicians' schedules so that they can focus on other issues.

- Many comprehensive digital assessment tools are evidence based, provide reliable and concise information, and can address a broad range of issues relevant to specific populations, such as college students.

- Reporting features are available in some such tools; these features can assist clinicians in treatment planning.

- Digital assessment tools can reach people in need who are reluctant to access services through traditional delivery methods.

- Such tools can help provide ongoing client assessment.

- Some such tools are available to the consumer 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- Using digital assessment tools can provide continuity of care with automated message reminders about appointments, medication reminders, or preventive health facts.

Examples of Outreach, Screening, and Early Intervention Programs for College Students

- MyStudentBody (http://www.mystudentbody.com): This Web site contains a suite of online behavioral health interventions targeting risk issues central to young adults, including alcohol and drug use, tobacco use, HIV/STD prevention and sexual health promotion, stress, and nutrition. The interventions are grounded in motivational enhancement and evidence-based behavior change principles.

- eCHECKUP TO GO (http://www.echeckuptogo.com): This Web site provides online personal alcohol risk assessment and motivational feedback. In addition, psychoeducational and interactive tools build awareness of the consequences of alcohol use and support social norms.

- AlcoholEdu (http://www.everfi.com/alcoholedu-for-college): This online alcohol education program aims to reduce alcohol use and associated risks. It incorporates video, audio, and interactive tools to promote awareness about risky alcohol use and skills to avoid risky drinking.

- Drinker's Check-Up (http://www.drinkerscheckup.com): This Web site provides online alcohol risk assessments for individuals. There are three sections to the site: “Looking at your drinking,” “Getting feedback,” and “Deciding whether or not to change.” The instrument is brief and non-judgmental about alcohol use.

JOHN: Well, that's a choice we'll have to make. We could just find a couple of packages that address stress management and alcohol and drug use and not get into other issues, because there are packages that deal with these two issues specifically. The other option is to go in a more comprehensive direction, but the choices in that direction are more limited, at least right now.

The other thing that I think is important is deciding what level of stress, impairment, or pathology we're going to address. Do we want to take a broad approach, something to introduce all students to various problems and options? Do we want to screen for certain problems like stress, alcohol, and drugs? Do we want to offer options for people with significant situational stress? What about supplemental interventions for students with pretty serious alcohol and drug or mental health problems? Let's clarify our goals first and how we would measure our desired outcomes. That'll bring clarity in choosing a program.

Another issue is the evidence base for these programs. At least one is listed in NREPP (http://nrepp.samhsa.gov), and some of the smaller, less comprehensive packages probably have some research behind them, too. We also want to look at the evidence in the evidence-based program. Is it one small trial or more substantial research that supports the program? There's a lot to think about here.

NANCY: Yeah, there is. Did you find any data to suggest that any of these programs would either cost us more or save us money in the long run?

JOHN: Well, some of the programs definitely have costs involved. Some charge on a per-use basis, others seem to have a yearly subscription, and I would imagine there are some programs you can just buy outright. As for savings, if we can serve more students with the resources we have, then that cuts costs per unit of service. That would help us meet our goals more efficiently. Maybe we can do a pilot program for a year or so with some specific funding to try to understand the program's effectiveness, costs, and benefits.

NANCY: Don't you think this will increase the client flow, rather than reducing it?

JOHN: I'm hoping it'll reduce our workload and increase the client flow at the same time. We'll be screening more effectively by having students do a self-assessment. Students, before they decide to come in to see us in person, can take a computer-assisted self-assessment, learn a little about stress management, and then self-screen for substance use disorders and mental illness. Kids who are really in crisis and need immediate services will be able to bypass that and come right to us. It also lets us free up treatment time by providing online psychoeducational information at different stages in a client's change process.

It would also be more efficient in terms of our staff workload. If young people at lower risk receive education and a brief intervention online, we can spend more of our time on those kids who are struggling with more intransigent issues. The risk profile that the program creates after someone takes the personal risk assessment can be a really helpful reference if the individual does come to see us. It's a good place to start; it shows what he or she has been doing and offers strategies to reduce risks for that person.

NANCY: What about information technology (IT) support? Do we need any other system supports? We also need to think about liability and make sure we are covered there. What happens if the person is suicidal? We'll need a good response plan in place, and we have to make sure we monitor results to look for signs of danger.

JOHN: This particular resource that I looked at, and maybe others out there, actually runs on a server at the company that administers the program, and no software is installed on our system. We're not in charge of making it run. We'll need to make sure that the company we choose has a good tech support team and find out how they support clients. We'd also need to know how fast they respond to problems. The other schools that use these programs could give us a good idea.

NANCY: But I'm sure that counselors will have to provide some tech support to help students who need help accessing the program. We would also need to ensure that our clinical team is adequately trained and feels comfortable using the technology before we roll it out.

JOHN: If we were to recommend this program to students who come into the clinic, we would have to know, for instance, if they have enough bandwidth in their dorm room or at home to run it and access the videos and interactive activities on the Web site. I would also want to check with the IT staff at some other colleges to see if they have the capacity for students to use the program over the college wireless network. Of course, if students access the program on their own time with their own computers or mobile devices off campus, these issues may not be as significant. Regardless, we'll have the clients sign an informed consent form detailing their understanding of the benefits and potential hazards involved in working with us online.

NANCY: Does this program meet the capability requirements that the college recommends for student computer use? We should ensure that all students have access to the same service.

JOHN: I think it would be important to see if they could access it via their mobile devices, because most students have smartphones now. I think they can also access all of the program elements from a desktop or laptop.

NANCY: So what happens? They answer a bunch of questions about their stress and they get recommendations? What happens if they answer yes to all the questions, and they are at very high risk for suicide? How does it work then, when there is no actual person with them?

JOHN: Well, most programs don't assess specifically for suicide. It looks like most of them warn users who are experiencing acute stress or are having suicidal thoughts or behaviors to call an emergency number or hotline like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

NANCY: Is there a message or a warning that says, “If you are experiencing extreme stress or other serious problems and you want to talk to a person live, here's what you should do?”

JOHN: What I really liked about this program is that when you subscribe, you can personalize the resources page to list the local resources in the community, at the community college, and at the health center. If someone is in crisis, they can call the emergency number here at the center.

There's another issue here that I don't want to overlook. Some kids from the college struggle with significant mental health and addiction crises—they're disabled with anxiety, have thought disorders, are depressed, or are drug dependent and scared to seek help. If this program can facilitate their entry into care, then we've provided a great service, and by intervening early, we may help them stabilize and begin recovery rather than getting worse before seeking treatment.

NANCY: You're probably right. Maybe some evaluative research after the program starts can help us track stabilization. How about the issue of confidentiality—we could potentially be collecting a lot of data on a broad spectrum of students. How do these programs control for that?

JOHN: In this particular program, data are stored on a secure server, not on an individual's computer or mobile phone. Each individual has a unique username and password they can use to access the program. There are algorithms behind the data so that individuals receive personalized feedback based on their response profile. There's also an administrative dashboard where administrators can see aggregate data as well as usage patterns.

Issues To Consider in Developing a Web-Based Outreach and Early Intervention Program

- Is the developer well known? Can the developer's references be checked? Does the developer have prior experience developing similar TAC programs? Is the program well supported by the developer?

- Are there empirical data to support that the program works? With which populations does it work? Are there published data? Does the program explicitly use evidence-based principles to guide behavior change?

- Are there a clear plan and resource list for users in significant distress or at high risk for self-harm?

- Is there assurance that all data entered into the system by participants are confidential and encrypted?

- Where will data be hosted, stored, backed up, and maintained?

- How will you obtain participant feedback about the program? How will you use that feedback in program development? Is the feedback aggregated or individual client data?

- Is there an administrative dashboard to monitor aggregate participant responses? Do these aggregate data reflect levels of impairment and actions taken by participants? Do the provided measures reflect the kinds of problems or questions participants have?

NANCY: So we would want to put something on the site about all of the 24-hour resources—hotlines and that sort of thing—that people can use in a crisis. It sounds interesting. Seems like there are a few more steps to take, but I think it's something that we should pursue.

JOHN: I agree. The program I'm thinking about tracks outcomes; we'd know how many students use it. We could ask students to evaluate it to see whether it's helping and what the limitations are. Maybe before we subscribe to the program, we could ask some students to get involved. That would take some of the burden off of us and help us test it to figure out what the best options are and whether they really meet the needs of the students.

After the meeting with Nancy, John researches the questions his administrator raised. He develops a plan that the university and the mental health center accept. They do live interviews with three companies that appear to meet their criteria, test each program, and check references. After analyzing their findings, they choose a program and begin a 1-year trial.

Part 2. Using screening tools to measure stress

This part of the vignette demonstrates how an online screening program can help students self-identify issues and situations in their lives that need attention.

As part of the program initiation, John is doing some trial demonstrations in classes on campus to gather data and establish a baseline stress level for students at his college. Next year, the program will be administered to all incoming freshmen, to at-risk students (students on academic probation, with disciplinary problems, or in violation of the college alcohol and drug use policy), and to any students who self-identify as needing counseling services. In conjunction with his audiovisual presentation, John describes a series of perceived stress situations and poses questions about alcohol and drug use in the past week to the students. He uses polling software to allow students to respond immediately to the questions, and then he reveals the aggregate classroom levels for each question in graphic form. John then invites students to assess where they stand in relation to the group average; some students are experiencing a good bit of stress, and some of these students may be drinking to cope with that stress at times.

He then tells the class that they can use the online program to learn more about stress and how to manage feeling overloaded without having to go to a therapist or counselor right away; he lets them know that they can take a personal assessment, get feedback, learn about stress and how it affects the body, and practice some healthy coping skills (e.g., exercise, meditation, deep breathing, music) to counteract those effects. John makes sure to tell them that, if after trying out the program, or even without reviewing the program, they want to seek professional help, they can visit his clinic or check the program Web site for contact information on other local resources.

After conducting one such classroom presentation, John stays to answer questions. Several students approach him, one of whom is Amy. She is concerned about some of her scores on the stress scale, which are higher than those of her peers. John makes an appointment for her to come to the mental health center so that they can talk in more detail.

JOHN: So Amy, how are you?

AMY: Sorta bad. I'm worried because my score on the stress test that you gave us in class yesterday was in the high range. I know I've been under a lot of pressure, but it worries me that my scores are so high. I really do think I'm having trouble concentrating. My grades aren't as good as they need to be to keep my scholarship, I'm having trouble sleeping, and the few friends I do have here tell me I'm being grouchy.

JOHN: Well, I'm glad you came in. Is there anything you're worried about?

AMY: I don't know if I'd call it worried. I'm from out of town. I'm here on full scholarship. I'm supposed to maintain a 3.0 grade point average, but last semester, I got a 2.8. So that's not good.

JOHN: Well, what happened?

AMY: The work is really hard, and I'm having trouble focusing. Maybe I just don't belong here.

JOHN: How do you think I could be helpful?

AMY: Fix me!

JOHN: What would that mean—to fix you?

AMY: If I lose my scholarship, I'm in trouble. I really need to get my grades up, so that's really stressing me. Then, on the other hand, because I'm so stressed, I have trouble sleeping, trouble motivating myself to study, trouble with almost everything. [She begins to tear up.]

JOHN: So, if I understand correctly, you need to find a way to bring your grades up, and that'll take off a lot of stress? Reducing the stress some will make it easier for you to get your grades up.

AMY: I guess so. I started feeling terrible; now I'm eating more, and I'm 10 pounds heavier than when I got here last fall. I spend so much time studying that I haven't made a lot of friends. Other people go out and have a good time, and I spend most of my time in my dorm room.

JOHN: Things are piling up.

AMY: I'm not sure that this school is the right place for me. But I also don't think I need counseling or therapy. By the time I get ready to come over here, then get back to the dorm, I've wasted at least a couple of hours that I could spend writing a paper or being in the library. I just need to get my grades up.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Web-Based Programs in Counseling

Advantages:

- Encourage self-assessment

- Reinforce stress management strategies/plans

- Foster provision of well-developed, clear action plans

- Open additional avenues for noncrisis support

Disadvantages:

- Lack the immediacy of in-person meetings

- Pose potential difficulties with understanding how to use the program

- Provide diagnostics without clear, scheduled follow-up and action plan

- Are contraindicated for work with suicidal, homicidal, or psychotic clients

In gauging the advantages and disadvantages of using Web-based counseling—or, indeed, any given technology in clinical practice—remember that, as always, use of good clinical judgment is imperative.

JOHN: I can understand your feeling that coming here just adds something else to your workload. But would you be willing to check something out? I have an idea about helping you get started on taking some action without having to come over here—something you can do on your own time, if you're willing to explore it.

AMY: Sure! It won't hurt.

JOHN: How are you with technology? Do you go online? Are you on Facebook?

AMY: Sure.

JOHN: Would you be willing to check out a Web site? It's the program I spoke about in class.

AMY: Well, I guess so.

JOHN: The first thing you'll do in the program is log in with a username and password that you devise, so that all of your information is confidential and accessible only to you. Once you're logged into the program, you'll then complete a personal profile that includes questions about your level of stress, the kinds of things that stress you out, and what you currently do to manage stress when you're feeling overloaded. It's a slightly longer version of the questionnaire you took in the classroom. You'll get feedback, tips, and information based on your profile. Then you'll have access to the information, interactive tools, and other activities in the program that you can review in whatever order you wish, whenever you wish. The tools and activities will help you identify triggers for what stresses you out, strengthen your coping skills for managing stress in healthy ways, and learn how to avoid stress, such as through time management strategies and getting good sleep. You can use these tools however you want, and you can add the ones that you find particularly helpful to a personal, interactive action plan that you can develop.

AMY: Can I use my phone to get into the program, or just my laptop?

JOHN: Do you have a smartphone?

AMY: Yeah.

JOHN: Then you can use your phone. Why don't I give you the link to the Web site? You can check it out right now.

AMY: You mean right now, like here in your office?

JOHN: Yes, let's be sure you can access the program. Then we'll take a minute to look over some of the content and see if you have any questions.

How To Encourage Clients To Use, and Continue Using, Web-Based Programs

- Give clear instructions about what to expect from the program and how to access the Web site.

- Demonstrate access and use of the program before the client leaves your office.

- Emphasize confidentiality and protection of private information (e.g., via passwords).

- Use a reminder system, such as text messaging, email, or an electronic calendar.

- Invite clients to report, in and out of the office, their successes and struggles with the program.

- Use secure video conferencing, encrypted email, or secure text messages to highlight client improvements and thereby promote motivation to continue using the program.

AMY: [Amy accesses the Web site on her cell phone.] This is pretty cool. There's a lot of stuff here.

JOHN: It's a comprehensive program to help people manage a variety of situations in their lives. I'm particularly interested in you looking into the stress management resources in the program. You can go on there and pick out the ones that you think will best meet your needs.

AMY: I don't know what that means.

JOHN: When you access the program, you'll answer some questions. Then you'll get feedback, just like you did in class earlier in the week. Based on your profile, it will highlight areas for you to check out on the site. I remember that you mentioned time management; this program has some tools to help you with that and also some other stress management techniques, like meditation and mindfulness.

AMY: I'm not really into that new-age stuff.

JOHN: Some people think of it as new-age stuff, but it might be something that you want to check out.

AMY: Is it like stretching?

JOHN: Something like that—stretching your mind.

AMY: That sounds interesting. How does that work?

JOHN: Well, it involves several steps. There are some assessment tools to help you evaluate how you use your time, and the program will give you information about ways to manage your time better. There are even some functions that actually help you make a plan for how you can use your time more effectively. Just go on the Web site and choose the time management and stress management tools you'd like to start with.

AMY: I'm not sure about this, but I'll check it out.

JOHN: Let's check back in a few days. Check out the program, and then we can talk about it.

AMY: But it was a hassle to come here. Is it okay for me to just send you an email or a text?

JOHN: Well, my reservation about that is that email isn't confidential. What if we do this: We have an encrypted email system here at the center, so I'll send you an email through that system right now. Then, when you reply to let me know how things are going in a week or so, that reply email will be encrypted. But be aware that anyone who might have access to your phone or your email will have access to our communication. Are you okay with that?

AMY: Well, not really. Maybe I should just give you a call.

JOHN: Okay, I'll look forward to your call in a few days. Do you have Skype or a similar video conferencing app on your computer?

AMY: Yeah. I use it with my parents every week and call friends back home with it.

JOHN: Great. Just call me, and we can videochat. My email is moc.chblacol@nhoj.

AMY: Okay. I like the idea of not having to come here every week. I'll just use the Web site in the next couple of weeks and check in by videochat to let you know how things are going.

JOHN: Sounds good. It was great to meet you, and I look forward to working with you.

AMY: Yeah. Me too.

During the next month, Amy uses the Web site on a number of occasions. She especially benefits from the time management, stress management, and sleep-related components of the program. She and John have two videochats during this month. She assures John that she will call if she begins to experience more distress than she is comfortable handling on her own.

Master Clinician Note: Counselors and administrators should be sure that clients fully understand how their agency's Web-based communications system works so that clients have realistic expectations about counselor availability, how long it may be before they receive responses to messages they send, and how the system is monitored. For example, will clients receive feedback? What are the client's expectations about feedback?

Part 3. Using Web-based interventions to support addiction recovery

Pete is referred to the student counseling center for violating the campus alcohol use policy; campus police found him sleeping in his car in the student parking lot, smelling strongly of alcohol and with an open six-pack of beer on the passenger-side floor of his vehicle. He was referred to the campus alcohol and drug policy office, where he was, in turn, referred to John's behavioral health center for an assessment. The following section of John's vignette details John's first meeting with Pete.

JOHN: Sounds like you have a lot going on, Pete. Do you have an idea of what you want right now?

PETE: I've tried to cut back on my drinking, and sometimes it works, but then I go back to it.

JOHN: What kinds of things have you tried?

PETE: Just willpower. I'll get drunk, then I'll feel terrible and miss class. My girlfriend threatened to break up with me because she said I got out of control one night. I just feel like I have to cut back, but I haven't been very successful doing that. Night before last, I drank a lot and then had to be at class yesterday morning. Between classes I went to the car, just to have a beer to take the edge off, and I guess I went to sleep. I must have been sleeping about 30 minutes when the cops rapped on the window and woke me up.

JOHN: Do you have some concerns about your drinking?

PETE: Yeah, but I've seen celebrity rehabilitation shows on reality TV, and I don't need that. I don't need to be sent away. I've tried Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), and there were some older folks in there who were fanatics. I don't want to be a fanatic about it. I just want to cut back on my drinking.

[John and Pete explore Pete's drinking history. Pete is cooperative in revealing a history of heavy drinking that began about 8 years ago and really became a problem while he was stationed at remote sites in the Air Force. Since his discharge 6 months ago, he has continued to drink daily. Upon returning to his hometown, he found that most of his old friends had moved on and weren't available. He started community college 3 months ago, but he hasn't really made friends. Mostly, he hangs out in his room at his parents' home or in a local pub, where he has met a few people. He has been dating a woman he met at the orientation session for the community college. He likes her a lot.]

JOHN: Well, let's talk for a few minutes about what you might want to do about your drinking. You say you aren't interested in treatment or in AA.

PETE: No! I don't want to go in front of a bunch of people and talk about my drinking.

[John continues to help Pete explore his options, including AA, other mutual-help programs, and inpatient and outpatient care, but Pete is adamant that he doesn't want community-based services. John assesses and does not find the need for detoxification or acute medical care. Pete must accept the recommendations of the counseling center as a condition of his staying in school, so John does have some clout, but at the same time, he wants Pete to feel ownership of his treatment plan. They settle on a three-pronged approach that includes an 8-week assessment group in which students with campus alcohol or drug infractions evaluate their substance use in a structured educational/discussion group setting at the college counseling center, completion of a Web-based alcohol and drug self-assessment that is part of the Web-based program adopted by the counseling center (along with a brief drug prevention education program that is part of the same package), and attendance at 10 online AA meetings.]

PETE: I have some reservations about this online AA thing. You say I don't have to give my name? All I have to do is go to the site and sign in?

JOHN: That is the beauty of it. You just go to this Web site. It operates similarly to other AA meetings and services. The Web site is http://www.aa-intergroup.org. All you need to do is sign in and then choose whether you want to attend an online meeting via videochat or telephone. The site also has chat rooms, email lists, and discussion forums. There are groups for specific populations, such as military personnel and veterans; people who are hearing impaired; gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered people; and even groups for specific areas of the country. You have lots of choices. Some meetings are open and can be attended by anyone, regardless of whether they use alcohol or have a drinking problem; other meetings are closed to all but people who have a drinking problem and a desire to quit drinking.

Evidence-Based Alcohol and Drug Use Prevention Education Programs for College-Aged Populations

Evidence-based online alcohol and drug use prevention education programs for college-aged populations (e.g., MyStudentBody, AlcoholEdu, eCHECKUP TO GO) are grounded in motivational enhancement and social learning theories. Such programs typically include a self-assessment with personalized feedback to build motivation for behavior change and education about the risks of alcohol and drug use to promote accurate risk perceptions. The more comprehensive online programs (i.e., MyStudentBody, AlcoholEdu) also offer audio or video peer stories and interactive tools that foster coping skills for reducing alcohol and drug use and help individuals develop their own action plans for change. Most of the available online programs are subscription based, so that a participating college/university can subscribe for use by their entire student body or by targeted risk populations. For more information, visit:

PETE: Does that mean that I have to have a desire to quit drinking totally?

JOHN: Well, I think for your first few meetings, you can be undecided about whether you want to stop totally. Part of the agenda for the next couple of months—the assessment group, the online meetings, and the work on the Web site that we discussed you using—is to help you decide what you need to do.

PETE: I guess I'd be willing to try it. I can't guarantee that I'll want to quit drinking entirely, but I'd be willing to try the treatment plan we've laid out and see what it's like.

JOHN: That seems fair enough.

PETE: There is something I haven't told you—my girlfriend says that I have to do whatever you recommend, or she won't go out with me anymore. I really don't know how much I actually want to do all of this stuff, but I'm willing to do it to keep my girlfriend and to stay in school.

JOHN: So the stakes are high and it might be worth it to take the risk.

PETE: Yeah!

Pete completed all three sections of his treatment plan. He attended an online AA group, which offered a good introduction to how AA works and dispelled some myths Pete had subscribed to about what meetings would be like. No participants were from his area of the country, but in the assessment group, he did meet two other men who attend Young People in AA, an AA group for people ages 16 to 27. He has attended two meetings with them and says he got a lot from attending. His attendance at online AA helped him make the transition to local meetings. He has had no alcohol in 3 weeks now and came to the decision to stop drinking of his own accord. He completed the alcohol and drug use section of the Web-based program and used the summary report of his risk profile and feedback in his work with John. Pete appreciates the ongoing ability to access the program online to reassess his risks and review material to reinforce his action plan for sobriety. Pete also has a friend who was willing to go to AA but did not have a car, so Pete introduced him to online AA, thus expanding his friend's access to AA support and giving Pete the opportunity to experience how helping others can be part of his own recovery.

Online Recovery Support

Online recovery support communities (some specifically for young people), such as AA and Marijuana Anonymous, hold online meetings that allow participation through the telephone or through voice or text chat features on a computer or mobile phone. Reliable online recovery resources include:

Vignette 2. Using Computerized Check-In and Monitoring in an Extended Recovery Program

Overview

This vignette demonstrates how computerized check-in and monitoring can support recovery for clients with co-occurring substance use disorders and SMI. The vignette includes examples of how checking in via a desktop computer, tablet, or mobile phone can benefit both clients and staff members in managing recovery; how to build clients' engagement with the check-in process as part of their recovery plan; how to teach the basics of computer use to clients who are not already computer literate; how computerized check-in can more readily involve hard-to-engage clients in taking responsibility for their recovery; and how to help clients use technology to maintain a connection to treatment resources after formal treatment has been completed. These technologies can be useful in a variety of behavioral health settings to help clients maintain self-management, recognize potential relapse factors, and see long-term progress in recovery.

Learning Objectives

- Identify how a computerized check-in process can be used in behavioral health settings.

- Introduce skills for counselors in educating clients, particularly those who are not computer literate, to the use of computers for check-in and monitoring.

- Address problems that can arise when clients do not check in or are unable to complete the check-in process.

- Demonstrate how to use a computerized check-in process to monitor progress and changes over time for a client in recovery from CODs. The term “co-occurring disorders” indicates that a person has both a substance use disorder and a mental disorder and that neither disorder is caused by the other; both are independent disorders that warrant individual treatment.

- Engage clients in taking responsibility for their recovery process.

Setting

Sondro is completing short-term restabilization in an inpatient CODs unit in a large city. He has been hospitalized on multiple occasions. He typically does well in the hospital and for a short time after release. After that, however, he tends to disappear from treatment, not take prescribed medication, use drugs, and show signs of paranoid thinking, all of which cascades into Sondro ending up homeless, unable to take care of himself, physically ill, and at serious risk for psychological and physical trauma. The staff wants to provide continuity of care that may help Sondro stay on track in his recovery. If unit staff can help him identify early symptoms, intervention may be possible before he gets out of control.

Staff members identify two approaches in care that may help Sondro achieve these goals. First, they recommend a transition from inpatient care to an intensive outpatient day treatment setting. After completing the day program, he will receive intensive support and monitoring by the ACT team at the local CMHC. ACT services are specialized, intensive services that often go beyond the traditional delivery model of care, which can be limited to the client coming into a clinic and having little access to after-hours contact. Some ACTs offer availability 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for some type of service; many include contacts with clients outside of the clinic setting.

Sondro's various service providers have agreed to a high level of treatment consistency and communication. One unifying element in Sondro's transition through these treatment environments is a computerized check-in process that Sondro will complete daily. The variables monitored by the check-in process are identified in the vignette. A significant benefit of the check-in process is the opportunity for Sondro to participate more actively in his own care and recovery.

Sondro's Story

Part 1. Developing client and counselor collaboration to support recovery

The treatment team wants to coordinate Sondro's care and transitions among the inpatient program, day treatment program, and ACT team services so as to provide ongoing care. Sondro will be attending the day hospital for a month to 6 weeks following his discharge from the inpatient unit for CODs. As in the past, Sondro has had a relatively uneventful inpatient stay. Once he gets back on his medications, regains physical strength, gets clean from cocaine, sleeps better, and feels safer, his paranoid ideation begins to diminish. He begins to engage with other clients; assumes responsibility for taking care of his physical needs; participates in group therapy on the unit; and, in general, appears contented. But the staff knows that when he leaves the hospital, he is at a high risk for relapse. He doesn't consistently take his medications, starts using crack cocaine, and loses his money and housing; particularly once he starts using cocaine, his paranoid ideation begins to manifest. The inpatient staff members, in consultation with the CMHC day hospital program staff and the ACT team, meet with Sondro to develop a comprehensive treatment and recovery plan. An essential part of this plan involves daily completion of a computerized check-in form, which monitors Sondro's functioning.

In this scene, Sondro is meeting with Irene, a nurse on the inpatient unit, and Mark, a member of the ACT team. Sondro has been active in developing his treatment and recovery plan, but he has some reservations about the computerized check-in process.

MARK: Sondro, we are all really excited about you, the inpatient and day hospital, and the ACT team all working together to create a really strong treatment and recovery plan for you this time. We really think this plan will make a difference in your recovery. I understand you have some concerns about using the check-in form, and we want to talk about that with you.

SONDRO: [after a brief pause] Yeah, I don't know about that.

MARK: Can you tell us a bit about your concerns?

Situations in Which a Check-In Process Can Be Particularly Beneficial

- Transitions from a higher to a lower level of care (e.g., from inpatient detoxification to an intensive outpatient program [IOP], from residential treatment to a halfway house)

- Periods of obviously increased stress (e.g., loss of domicile or intimate relationship, death of a loved one) with risk of relapse to substance use or exacerbation of mental illness

- Adjustments or alterations of medication for mental or substance use disorders

- Increases in a client's need for motivation and support to continue treatment (feedback on the client's own responses can be very useful)

- Repeated readmissions and difficulties in linking levels of care in recovery

- Introductions of new treatment methods or approaches not familiar to the client

SONDRO: Well, I just don't know about what you want me to do there in the mornings.

Master Clinician Note: Clients who express reservations about a technology-based intervention, as Sondro is doing, may be reacting to a combination of discomfort with using a computer, the introduction of something new into their daily regimen, and a manifestation of symptoms related to substance use or mental illness. For Sondro, part of what drives his reluctance is suspiciousness resulting from his paranoid illness. Staff members have already ensured that Sondro has basic literacy skills to handle questions on the computer screen, but it is worth noting that a lack of basic literacy skills can contribute to client resistance in situations like Sondro's.

MARK: Well, Sondro, why don't we work with you on this to help you get comfortable with the computer? You can try it out every day for the last few days you're here on the unit, and we'll have somebody right there with you in case you have questions. We can also maybe show you the computer you'll be using when you get to the day hospital. Would that take care of some of your concerns?

SONDRO: Well, I don't know.

MARK: I can understand that you have reservations. Is one of those that you worry about who might have access to the information?

SONDRO: Maybe a little.

MARK: I can reassure you that only the treatment team where you are currently in treatment—like right now, you're in the inpatient unit—and I will have access to the information. We do want to know how you're doing, and we especially want to be able to show you how much you're improving over time. The information you enter into the check-in form can tell us that.

SONDRO: So what kind of information does this thing collect?

How To Engage Clients With Automated Check-In Systems

To appeal to clients, there must be some noticeable benefit in the use of any type of automated clinical tool. The following strategies help increase the likelihood that clients will use and benefit from an automated check-in system:

- Encourage the client to tailor the information exchanged to his or her own recovery goals.

- Give something back. The benefits of one-way reporting to a clinician on symptoms may not be obvious. Helpful responses, delivered either in person or via automated messaging, should be tailored to the client's needs and desires.

- Allow the client to practice using the system with a staff member present to assist with the process and answer any questions that arise.

- Be clear and direct about the risks and benefits of participation, and encourage the client to make his or her own choice about participating.

- Engage peers who have found the system useful to help the client acknowledge benefits and practice using the system.

- Overcome equipment-related barriers by providing access to necessary devices, such as mobile phones, tablets, or computers.

- Use motivational interviewing to assess the client's willingness, plans to engage, and perceived obstacles.

MARK: Mostly, it's just information about how you're doing. For instance, we'll ask some questions about whether you're enjoying life, whether you're taking your meds, how your housing situation is going. We'll ask you about whether you're having cravings or feeling shaky about your recovery and whether you're having any symptoms, stuff like that. It takes about 10 minutes to complete, maybe a little longer until you get used to it.

SONDRO: Couldn't you just ask me the questions?

MARK: Well, we could, and we probably will continue to ask you some of them throughout the course of a day. But what we really want to do here is help you figure out where you're at when you feel the most comfortable, so when things start to go haywire, you'll notice, and you can kick up your wellness/recovery action plan. If you want, you can ask us to help you out, too.

There's one other thing that I didn't mention earlier. The questions on the check-in form are customized to you. Everybody who uses the program has the questions written specifically to address their needs. Of course, there are some that are the same for everybody, like, “How do you feel this morning?” But then there will be some questions for you about your housing, because that's been a problem in the past; about your disability money and whether it's secure; about whether you're taking your meds—things that you've said you want help with and worry about.

SONDRO: What if I get the questions wrong?

MARK: There aren't really any right or wrong answers—just your thoughts on how you're doing. And if you need help answering some of the questions, there will be someone available to help you. I think you'll see that it is really pretty easy and gives you time to think every day about how you're doing and what you need for that day.

SONDRO: Uh huh. What if I don't want to do it?

IRENE: Nobody's going to force you to do anything you don't want to do. We do believe this will be helpful, and we think you'll find it helpful, too, as we go along. But you have to give it a try if any of us are going to be able to see whether it works. A person will be there to help you with the computer and with completing the questions when you get to the day hospital.

MARK: So what do you think?

SONDRO: I guess I can give it a try. I'm a little concerned about people collecting data about me on computers.

MARK: I can understand that. Let me assure you that the information is for our staff—the people you know—and the only data are about how you are doing and what you have said you wanted us to help you with. For now, could you and I just give it a trial run? There's a computer here on the unit, right by the nurses' station, just for clients. I want to show you how to log in, access your own check-in form, work a keyboard, what kind of responses you'd put in, and so forth.

SONDRO: I can work a computer. I know how to use a keyboard. Just show me the form.

MARK: Okay, let's do it.

How To Help Clients Overcome Resistance to Computerized Check-Ins

Common points of resistance that clients have to computerized check-in include:

- Reluctance (shame, embarrassment) about using a computer because of a lack of exposure to the technology and training in how to use it.

- Limited reading skills or illiteracy.

- Ambivalence about recovery—about having their craving, substance use, and mental illness symptoms logged for clinicians to see and reflect back to them.

- Annoyance at being made to do something by someone they perceive as more powerful.

- General concern or anxiety about doing something new.

- Fear that the information provided will be used against them.

To overcome resistance to computerized check-in, you can use the same strategies you might use to motivate clients to complete paper check-in forms or other tasks:

- Help clients see the value of check-in so they will want to do it on their own.

- Help clients link progress toward one of their goals with the use of the program.

- Use motivational interviewing skills when starting clients on a new task.

- Work with clients to identify and overcome perceived obstacles to using the program.

- Emphasize the importance of collecting data for clients' well-being.

- Help clients feel like they are part of their own recovery teams by completing check-in.

Mark and Sondro do a trial run on the computer on the inpatient unit. Mark helps Sondro access the program and helps him create a username and password, and then Sondro completes the check-in process without problems. Sondro's username and password are stored by Mark in case Sondro forgets or wants to change them. Mark also emphasizes that Sondro needs to keep his password and user name secure and explains to him how to do so. The questionnaire takes about 12 minutes to complete. He does take some time to read the more detailed questions about drug use and asks Mark about one of the drugs listed (ketamine), saying he isn't familiar with it. Mark also asks Sondro to choose some questions that he would like to include in his check-in form from a list of optional questions. Sondro picks one about attending 12-Step meetings and another about physical exercise, two aspects of his relapse prevention plan that he has struggled to maintain in the past. A sample check-in form is presented in Part 2, Chapter 2, of this TIP.

How To Facilitate Client Computer Access in Treatment Settings

- Create private spaces where clients using computers can't be seen by rest of the client population.

- Provide trained staff members or peers to help troubleshoot.

- Make available written how-to sheets about operating the hardware or accessing support sites.

- Attend to Internet privacy and security standards by installing up-to-date virus, spyware, and malware protections.

- Protect client privacy by setting machines to delete cookies, search histories, and other private information that may otherwise be stored on the computer.

- Provide easily accessible links to support and education sites that you know are reputable.

- Block access to nontreatment sites to ensure that clients spend computer time on treatment-relevant activities rather than personal business (e.g., visiting social media sites).

- Offer basic computer classes taught by volunteers from the community.

- Consider firewall implications when using networked computers for client access to protect against unauthorized access to electronic clinical record systems or other confidential business applications.

Check-In Example

In a psychiatric inpatient and day treatment program in Western Australia, touchscreen access has been provided to clients participating in CBT groups. Clients complete the World Health Organization-5 Well-Being Index, a five-item measure of psychological well-being, each day. Therapists provide clients with a printout graphing their progress compared with expected progress and discuss results with clients in a weekly group. Therapists can use the well-being trend information to discuss treatment progress and realign treatment plans with their clients. An evaluation of the use of the touchscreen check-in demonstrated high levels of staff and client satisfaction with the tool, and client reports indicated that use of the technology increased their discussions with therapists about treatment progress and enhanced their understanding of their progress.

Sondro completes his inpatient stay without incident, filling out the check-in form each morning after breakfast. On the last two days of his inpatient stay, he works with a case manager to make the transition to a group home, where he will live for 3 months. After his stay in the group home, he will move to permanent supportive housing. Despite some distress about transitioning to the group home, he is compliant and shows no resistance in leaving the unit.

Part 2. Service provider collaboration

Mark meets Audrey, Sondro's primary counselor on the CODs day hospital unit. Audrey is not familiar with the check-in process and has questions about its efficacy.

MARK: Audrey, thank you for meeting with me today. I've gotten permission from Sondro to talk to you. I want to explain a little about the ACT team. Do you know what it is?

AUDREY: Well, we've worked with ACT teams before, but primarily as a referral resource when people leave the day hospital unit, so could you fill me in a bit?

MARK: Sure. ACT stands for assertive community treatment. It's a treatment approach that uses interdisciplinary staff members to provide community-based treatment and daily contact with clients, including services after hours. The team provides direct interventions to maintain stability of housing and entitlements and supports client compliance with prescribed medication regimens. When clients begin to relapse to drug use or mental illness, the team provides assertive treatment to reengage the client in recovery-oriented activities and family or peer support systems. Our ACT team is assigned to Sondro. I'm the case coordinator, but I want to emphasize that everyone on the team will be involved with Sondro's recovery. We'd like to work closely with you and your program to ensure that Sondro gets the best care possible from all of us.

Master Clinician Note: The privacy and confidentiality standards and regulations that typically apply to behavioral health services, including Title 42, Part 2, of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, also apply to electronic exchanges. As with any exchange of health records that are subject to 42 CFR Part 2, clients must provide written consent to share information across providers. Many states have laws that require consent for sharing information related to mental health. Offering clear, simple descriptions of the ways confidential information will be exchanged and providing a rationale for the exchange, along with an explanation of the risks and benefits associated with electronic information exchange, will help clients make informed choices about how their information is shared across providers and organizations. Providers must ensure that transmission of protected health and other confidential information is completed securely. See Part 2, Chapter 1, for more information on secure email and Web access.

AUDREY: That sounds great, and I look forward to working with you. Will you be involved with Sondro while he's here in the day hospital?

MARK: On an as-needed basis, yes. We want to collaborate on his care so that the transitions can be smooth and less traumatic. In addition to communicating with you and your staff, we also want to use a new tool that we think is especially useful for clients like Sondro, who in early recovery are particularly susceptible to relapse because of the combination of substance use and mental disorders. We have this computer-based program that'll help all of us facilitate Sondro's care. We don't want Sondro to disappear and then find out after a couple of days that he's begun using again or has been staying in a crack house. We want to find out early when he starts to lose momentum in terms of his recovery. The things that this program will track are the same things that you pay attention to: his participation in meetings, what his abstinence looks like, whether he's accessing intensive outpatient services and coming on time, how connected he is. It also tracks things that we look at in terms of mental health. Is he taking his medication? Is he having troublesome symptoms? Are the symptoms getting better or worse? You have a client computer that he can use here on the first floor, and every day, he'll check in. It allows us to go to the Web site and see how he's doing. This means that at the beginning of each day, even if we haven't asked about those things, we'll know how he's doing because the information will all be there. And there's another section of this site that will allow you and me to coordinate his care and communicate with one another.

AUDREY: Do you think he's actually going to tell the truth if he starts using drugs again?

MARK: We won't know for sure that he is telling the truth about every detail. But we'll also have some objective data in the mix—for instance, he is either using the check-in process or he is not. And we'll know if he checks in and says he is going to treatment, but you haven't seen him there. Then I'll know that, too, and I'll send someone on the team out to find him and offer him support.

Master Clinician Note: In general, studies of computer-assisted self-interview instruments demonstrate that clients are sometimes more forthcoming about sensitive, embarrassing, or shameful information when disclosing to a computer program than they are during in-person interviews (Islam et al., 2012; Richens et al., 2010). Web-based daily completion of check-in forms build on these studies by providing clients an opportunity to check in without talking directly to providers. A daily check-in process also provides a structure for collaboration between the client and the provider and a way for the client to be more actively engaged in recovery.

AUDREY: I don't see how this is any different from what I get from him every day. I see whether he is there, I analyze his urine screens, I observe his participation and see when he's getting upset. It isn't too hard to tell when people are getting sick again. Frankly, it just seems like another kind of paperwork.

MARK: I can see how it would appear that way, and no, we don't want to add to your workload. In fact, we think it will actually reduce it, eventually. This is a little more work on the front end; it's a change in routine as we're introducing a new treatment modality. The good news is that you can use the information from the check-in form in your clinical record keeping and reduce some of your charting. But more importantly, it's an opportunity for Sondro to participate in his recovery. Here's a printout of the check-in form we use. It's pretty comprehensive and, at the same time, pretty quick to complete. Your role in Sondro's care is still of the utmost importance, and your clinical judgment in determining how Sondro is doing will never be replaced. This is simply a tool to allow Sondro to play a greater role in his recovery and assist him with recognizing the warning signs that may indicate potential difficulties in his recovery.

Master Clinician Note: To support the client in repeatedly filling out the check-in form over time, the form must be relatively brief in length, take only a few minutes to fill out, and be meaningful to the client to sustain the motivation to complete it each day. The goal is to identify a few questions that are meaningful and important to both the client and the provider.

AUDREY: So I just have to pay attention to whether something is going wrong. What do we do when the data indicate that Sondro is headed for problems?

MARK: Well, first, we'll compare notes and get a better picture of what's happening. We can then talk with Sondro about our concerns and modify the treatment plan to better address the situation at hand. Our broad treatment goals for Sondro will always be to support his recovery from his substance use disorder; manage his mental illness; and help him maintain adequate family, housing, health, financial, social, and other supports that he needs to make it in the community. We both know it's going to be a long haul for Sondro, but I think the computer-assisted check-in process will be a great boost to him, especially in his early recovery.

Alternative Approaches for Conducting Check-Ins

- Voicemail or interactive voice response systems

- Mobile phone applications

- Secure Web-enabled tablets or personal computers

- Structured email

- Paper and pencil checklists entered into a computer tracking system

AUDREY: Are any of the questions on this check-in form going to be about his drug use?

MARK: Yes, he will be asked about things like cravings, slips, getting to his meetings outside of his IOP, if he is having any troubles there—for instance, with other clients, because you won't always be around to monitor him. Also, we can customize the form to include information specific to your program, information you particularly would like to have. In fact, we asked Sondro to identify the relapse risk factors that were most important to him, and he identified attending meetings and participating in his exercise group as areas he would like to track. The data the check-in form collects can help him see the connections between his symptoms and his behavior.

Master Clinician Note: The ability to customize the check-in form creates clinician buy-in by meeting the needs of their programs and also produces client buy-in, as clients can add items they identify as important metrics of their own recovery. Initially, it is helpful to ensure that support staff members also understand the program, can adequately answer client questions, and are supportive of their clients' use of the program.

AUDREY: Well, it sounds interesting.

MARK: Good. I don't want to lose sight of one of the things I consider most important. In terms of his recovery, this is a proactive act on Sondro's part every morning. He takes a greater stake in his recovery by completing this form. It's one more step in involving him in his own recovery.

AUDREY: You're right, and I'm willing to give it a shot. Maybe Sondro's case is a good one with which to try this out.

Part 3. Maintaining the recovery connection after IOP completion

Sondro is doing well, staying abstinent, taking his meds regularly, and has seen the ACT team psychiatrist at the CMHC for a medication check. His stay in the IOP was extended by 2 weeks to give him more time to stabilize. His contact with the ACT team has been primarily to support his IOP stay and to help him make adjustments in the community. The team is working with a local housing agency to help Sondro obtain permanent supportive housing in the community. In the meantime, he continues to live in the group home. He has regularly attended sessions at the IOP with only a couple of setbacks that were subsequently resolved. One occurred during a week when Audrey went on vacation; Sondro became suspicious and upset with the counselor who was leading the group for that week. The other occurred when Sondro got angry at another client in the group and refused to come back to the group for 2 days. With help from Audrey, he relented and reengaged with the group. After the first week of practice, completing his check-in form became a regular part of his day, and he reported that he actually enjoyed letting people know how he was doing. He felt proud to be able to report his progress and knew that both Mark and Audrey were aware of his reports. On a couple of occasions, Audrey used information provided by the check-in process as part of her ongoing monitoring and to give feedback to Sondro about his progress. Together, they charted trends and positive changes that Sondro had made.

Part 4. Sondro graduates from the IOP

Sondro has graduated and will not have day-to-day contact with the IOP staff any longer. Mark meets with Audrey about the recovery plan the IOP developed with Sondro, which includes checking in daily. Mark also introduces the idea of sending text message reminders to Sondro. These may be particularly important once he leaves the group home to enter permanent supportive housing in the community. Audrey will not be as involved because Sondro is no longer in her program. After a few months, if Sondro is doing well, the frequency of the Web-based check-in process can be reduced, but for now, the staff members of both programs think that sticking with the current frequency is best so as not to introduce another change in Sondro's life.

MARK: Sondro has graduated from your program and seems to be doing really well. Is that your impression, too?

AUDREY: I'm really happy for him. He has done well. He's still at high risk, and in just 24 hours, he can go right off the edge, but he'll be in our once-a-week continuing care group. If we see him getting shaky in his abstinence, we'll address that. If I think he is showing significant symptoms of mental illness, I'll call the ACT team. We can't enforce his attendance, but we expect that he will continue. He's been going to the Double Trouble in Recovery group that meets here every day, too, and we hope he will continue that, so we're really happy with his outcome. I have to say that I'm impressed at the data that we got back from the check-in process. We were really surprised. I didn't have much belief that it would make a difference, but it was nice for me to be able to get a quick picture, in a matter of minutes, of Sondro's functioning in a broad sense. I think the messages that appeared when he logged on to the system really helped him see that we were looking at the information and recognizing his positive progress.

Master Clinician Note: Double Trouble in Recovery is a 12-Step program for people with CODs. It is based on the 12 Steps and 12 Traditions of AA. Other programs, such as Dual Recovery Anonymous, may also be available in your area. Sometimes, the term “double trouble” is used to indicate that someone has a substance use disorder and also has a process addiction, or that someone participates in multiple 12-Step programs.

MARK: We'll still be monitoring and reinforcing his progress by having him check in. There could be a shift to a smartphone for the morning check-in process as he moves out into the community, but it will function in the same way as the desktop here at your program. Right now, the cost of a smartphone might be prohibitive for him, but in the future, the cost may come down. I'm also happy that he's willing to go to your continuing care and the Double Trouble group. I think we'll build in some reminders on the morning check-in process for Sondro about attending those meetings.

AUDREY: He's supposed to be going every day. Often, we find that he has trouble bonding in those groups, but we're going to support him in doing that. He seems happy there so far. I'm going to report to our administrator that we ought to do this check-in process for all our clients.

[Later, Mark meets with Sondro after his graduation ceremony from the day hospital program.]

MARK: So, Sondro, things seem to be working out fine. You're doing a great job.

SONDRO: Thank you.

MARK: You've had trouble for many years, and this time you really walked the walk. You're maintaining your abstinence, going to your outpatient treatment, taking your meds so the symptoms don't get in your way, and working on your physical health by participating in a walking group to get some exercise. I think you have a lot to be proud about.

SONDRO: That computer thing, it's pretty cool. It's not too hard and I like the color bars. When it's all green, I feel good. I like that when I finish, if I'm doing well, the bar turns green, and if I'm having a few troubles, it turns yellow. I haven't had but a few days where the bar was red, meaning I'm in big trouble.

MARK: That's the idea—for you to be in charge of your recovery. Checking in is one part of that, just like being in charge of keeping appointments, taking your meds, and being aware of times when you might need additional help. Audrey told me you now have a cell phone.

SONDRO: I do, but I'm worried that people can find me too easy.

MARK: Well, you don't mind us finding you, I hope.

SONDRO: No, you're okay.