Introduction

The maxilla is the most important bone of the midface. It has a central location and provides structural support to the viscerocranium. It has functional and aesthetic significance as it has a fundamental role in facial architecture, separates the nasal and oral cavities, forms the upper jaw, and contains the maxillary sinus.[1][2]

Structure and Function

The fusion of the right forms the maxilla and left maxillary bones at the midline. Each maxillary bone has the shape of a pyramid, it's base adjacent to the nasal cavity, its apex being the zygomatic process, and its body constituting the maxillary sinus.[3] The maxilla connects with surrounding facial structures through four processes: alveolar, frontal, zygomatic and palatine. It articulates superiorly with the frontal bone, the zygomatic bone laterally, palatine bone posteriorly and with the upper teeth through the alveolar process inferiorly. Anteriorly, it forms the inferior and lateral borders of the pyriform aperture and articulates with the nasal bones medially at the anterior border of the frontal process.

Alveolar Process

The alveolar process serves as an anchor for the teeth of the upper denture. It has a horseshoe configuration, with the curved portion facing anteriorly. Located on the most inferior plane, below the hard palate, it extends posteriorly beneath the maxillary sinuses to terminate with the maxillary tuberosity. The alveolar arteries, alveolar nerves, and periodontal ligaments penetrate through channels within the alveolar process to respectively irrigate, innervate and fix the upper teeth.[4]

Palatine Process

The left and right maxilla fuse at the midline through the palatine processes where they form the median maxillary suture. Superiorly, the union of the palatine processes forms the anterior nasal floor and the inferior border of the pyriform aperture at its most anterior aspect. Inferiorly, the anterior portion of the hard palate forms, where the incisive canal is present.[5] This osseous channel communicates the nasal and oral cavities and serves as a conduit to the nasopalatine nerve and the sphenopalatine artery. Superiorly it initiates in the superior nasal (Stensen's) foramina that lie on both sides of the nasal septum and runs inferiorly to terminate at the incisive fossa in the oral cavity, located beneath the incisive papilla and behind the medial incisors.[6]

Zygomatic Process

The zygomatic process is the most lateral portion of the maxilla. It forms the superolateral border of the maxillary sinus and is superior to the first maxillary molar, contiguous with the alveolar process inferiorly and with the frontal process superomedially. Along with the alveolar process, the zygomatic process plays a crucial role in providing structure to the midface.[5] It articulates laterally with the zygomatic bone and has an essential function as it is responsible for the projection of the malar eminence and facial width.[3] On the anterior surface, lateral to the zygomatic process and medial pyriform aperture, a depression is formed known as the canine fossa, which constitutes the anterior surface of the maxilla.[7] Also on the anterior surface, inferior to the zygomatic process and superior to the alveolar processes, another depression forms known as the zygomaticoalveolar crest, an essential structure in classifying maxillary fractures.[2]

Frontal Process

The frontal process lies superiorly and medially relative to each maxillary bone. Each frontal process articulates with the frontal bone superiorly and the nasal bones medially. It forms the anterior wall of the nasolacrimal groove and contributes in shaping the inferior and central portion of the forehead as well as to the nasal bridge through its union with the frontal and nasal bone.[8][9]

Maxillary Sinus

Each maxillary body is hollow and contains an air-filled cavity in the center, the maxillary sinus. The maxillary sinus is the largest of the paranasal sinuses with an approximate volume of 15 ml in adults. Similar to each maxillary bone it has a pyramidal shape, with the base being the medial wall of the sinus which faces the lateral nasal wall and its apex situated laterally towards the zygomatic arch. It extends from the premolars, anteriorly, to approximately the third molar, posteriorly. As an anatomic variant, it occasionally traumatizes the zygomatic process superolaterally and the maxillary tuberosity inferolaterally.[5] The roof of the sinus forms part of the orbital floor and contains the infraorbital canal which carries the infraorbital neurovascular bundle which exits through the infraorbital foramen, approximately 1 cm below the infraorbital rim.[10] The floor lies superior to the alveolar process and is near the molar apices, its lowest point being in the first molar area. The sinus floor can be at the same level as the nasal floor to about 1 cm below it, varying with age. The medial wall forms part of the nasolateral wall and contains two vital structures, the maxillary sinus ostium, and the nasolacrimal duct. The maxillary sinus ostium is located in the anterosuperior portion of the medial wall and drains into the ethmoid infundibulum which opens up into the middle meatus in the nasal cavity. The nasolacrimal duct originates at the medial wall of the orbit and travels downward and courses medially through the maxillary sinus, anterior to the sinus ostium to eventually drain into the inferior meatus.[8][9]

Embryology

Maxillofacial development starts at the fourth week of gestation with the formation of the five facial prominences around the stomodeum, the primordial mouth and the topographical center of the face during embryonic development.[11] The first pharyngeal arch and neural crest cells contribute to form the five facial prominences: paired maxillary, paired mandibular and frontonasal prominence.[11][12][13] The stomodeum is demarcated cranially by the frontonasal prominence, laterally by the maxillary prominence and inferolaterally by the mandibular prominence. The maxillary prominences give rise to the secondary palate, the majority of the maxilla and the lateral upper lip.[14][15]

By the end of the fourth week, the lower half of the frontonasal prominence gives rise to the nasal placodes, which divide into paired lateral and medial nasal processes, with the nasal groove dividing them. At the end of week six the medial nasal processes fuse to form the philtrum, and at the end of the eighth week, they fuse with both maxillary processes to form the intermaxillary segment to form the upper lip and the primary palate. Specifically, the primary palate forms from a deep structure of the intermaxillary segment known as the median palatine process. The lateral nasal processes form the nasal alae.[11][13]

The secondary palate begins to develop during the 6th week of development. Outgrowths of the maxillary process, denominated palatal shelves, grow vertically on both sides of the tongue. During the seventh week, as the jaw elongates and the tongue descends, the palatal shelves acquire a horizontal position.[13][14] The shelves then fuse at the midline to form the secondary palate and fuse anteriorly to the primary palate and nasal septum, followed by replacement of the palatal mesenchyme by muscle and bone that correspond to the hard and soft palate. At the central fusion point in between the primary and secondary palate, the nasopalatine canal forms and posteriorly becomes the incisive canal.[6] Fusion of the palate is completed by the tenth week and fully forms by the twelfth week of embryonic development.[11][13]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the maxilla is via branches of the maxillary artery. The maxillary artery is a terminal branch of the external carotid artery; it originates posterior to the upper portion of the mandibular ramus, runs anteriorly in the inner side of the mandibular ramus, and enters the pterygopalatine fossa to terminate with the pterygopalatine artery.[16] It has three major segments: mandibular, pterygoid, and pterygopalatine, from proximal to distal, respectively.[16][17]

The pterygopalatine segment is the principal blood supply of the maxillary region. The pterygopalatine segment is in close relation to the pterygopalatine fossa from where it branches into five vessels: posterior superior alveolar artery (PSAA), infraorbital artery (IOA), greater palatine artery (GPA), sphenopalatine artery (SPA), and vidian artery (VA).[17] The VA is a recurrent branch and courses posteriorly to enter the Vidian canal, supplying the mucosa of the pterygopalatine fossa and nasopharyngeal cavity.

The PSAA runs towards the zygomatic process and has a prominent curve on its inner surface and courses towards maxillary tuberosity with branches supplying the upper molars and premolars. The IOA runs along the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus and enters the inferior orbital fissure and enters the infraorbital canal, supplying the lacrimal sac, upper incisors, canines, and mucous membrane of the maxillary sinus. The GPA emerges near the PSAA and descends through the greater palatine canal to exit through the greater palatine foramen to supply the hard palate. The SPA is the terminal branch of the pterygopalatine segment. It enters the nasal cavity posterior to the nasal turbinates to supply the nasal septum and turbinates.[16][17][18] The posterior septal branch of the SPA courses through the incisive canal to form an anastomosis with the GPA.[6] The PSAA, IOA, GPA, and SPA all supply the maxillary sinus walls and mucosa.

Nerves

Innervation of the maxilla is via the maxillary nerve (V2). V2 constitutes the second branch of the trigeminal nerve, the fifth and largest cranial nerve.[19][20] It has its origin at the trigeminal ganglion and serves, principally, as a sensory nerve. It exits through the foramen rotundum to enter the pterygopalatine fossa where it gives off several branches.[17] Sensory innervation of the maxillary structures is provided by several structures including the sphenopalatine ganglion, the infraorbital (ION), posterior superior alveolar (PSA), middle superior alveolar (MSA), anterior superior alveolar (ASA), palatine (PN) and nasopalatine (NPN) nerves.[16][19][21][20]

The ION is a direct extension of the maxillary nerve. It courses anteriorly through the infraorbital canal where the middle and anterior SAN arise, as well as giving off branches to innervate the superior and medial maxillary sinus walls.[8] Finally, it exits through the infraorbital foramen giving off branches to provide sensory innervation to the lower eyelid, nose, cheek and upper lip.[21]

There are three superior alveolar nerves: PSA, MSA, ASA. The PSA emerges in the pterygopalatine fossa before V2 enters the infraorbital canal. It descends on the maxillary tuberosity and penetrates the inferior alveolar canal on the infratemporal maxillary surface providing innervation to the molars and posterior wall of the maxillary sinus as well as giving off branches that join the MSA and ASA to form the alveolar plexus.[9][11][12] The MSA branches off the ION during its course through the infraorbital canal and courses along the posterolateral wall of the maxillary sinus to innervate the premolars and contribute in the innervation of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus.[8][9][21] The ASA arises from the anterior third of the ION and runs inferiorly in the anterior maxillary wall to innervate the lateral nasal wall, maxillary incisors and anterior wall of the maxillary sinus.[8][9]

The PN is a branch of the sphenopalatine ganglion and divides into the greater palatine (GPN) and lesser palatine nerves (LPN). The GPN is the anterior branch of the palatine nerve. It exits through the greater palatine foramen opposite to the third molar and runs in the inferior hard palate to innervate the hard palate and the palatal gingiva. Additionally, the GPN provides innervation to the inferior wall and ostium of the maxillary sinus.[8][21]

The last branch involved in the innervation of maxillary structures is the nasopalatine nerve (NPN). The NPN is a branch of the sphenopalatine ganglion. It begins its course entering the nasal cavity through the sphenopalatine foramen, runs along the roof of the nasal cavity providing innervation to the nasal roof and septum. Posteriorly, it descends along the nasal septum to enter the canal of Stensen and travel through the incisive canal to emerge on the hard palate through the incisive foramen. It provides innervation to the palate and palatal gingiva adjacent to the canine teeth.[6][21]

Muscles

The muscles of the midface include the nasalis, levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (LLSAN), levator labii superioris (LLS), zygomaticus minor, zygomaticus major, levator anguli oris (LAO), buccinator and orbicularis oris.[7] Only the nasalis, LLSAN, LLS and LAO have their origin on the maxilla. The facial nerve innervates all muscles of the midface.[7][22]

The nasalis muscle has its origin on the maxilla and lateral nasal sidewall and sends fibers over the nasal dorsum to meet the contralateral muscle. Its contraction opens the nostrils during deep inspiration.[22]

The LLSAN has its origin on the upper frontal process of the maxilla and extends inferiorly into the orbicularis oris. Its function is to evert the lip, dilate the nasal ala and deepen the nasolabial fold.[7][22]

The LLS originates on the inferior orbital margin, near the infraorbital foramen, and inserts in the orbicularis oris. Its contraction everts the upper lip and deepens the nasolabial fold.[7][22]

The LAO originates from the canine fossa and inserts on the lateral commissure muscular slip, also known as the modiolus.[22] It functions moving the oral commissure, contributes to smiling and in the movement of the nasolabial fold.[7]

Surgical Considerations

Blood Supply

The maxillary sinus is irrigated by the PSAA, IOA, GPA, and SPA. It is essential to determine the sites of the IOA and PSAA for surgical planning as they anastomose and form a double arterial arcade that surrounds the maxillary sinus and damage to these vessels can cause bleeding.[8]

Intricate knowledge of maxillary artery anatomy is necessary for the treatment of posterior epistaxis. It accounts for 5% of cases of epistaxis and can be treated with endoscopic ligation or electrocauterization of the sphenopalatine artery and palatine artery to control persistent bleeding.[16]

Nerves

The superior alveolar nerves innervate the maxillary sinus walls and mucosa. Their paths as they innervate the maxillary sinus presents a safe area at the anterior maxillary region where bone can be safely removed with minimal risk of damage to the superior alveolar nerves.[9] This margin of safety becomes especially relevant during a Caldwell Luc procedure where the maxillary sinus is accessed through the canine fossa to replace sick mucosa with healthy mucosa in patients with maxillary sinusitis.[23]

LymphaticsIn the management of oral maxillary cancers, a sentinel lymph node biopsy is a diagnostic option. The sentinel lymph node is frequently uniquely located in cervical lymph node levels I, II, and III with less frequent involvement of parapharyngeal and cervical lymph nodes in combination.[24]

Clinical Significance

Detailed knowledge of maxillary anatomy is essential when dealing with the trauma of the midface. The most recognized classification of midface trauma is the LeFort classification for maxillary fractures. French surgeon René LeFort created it in 1901. It divides midface fractures into three categories (LeFort I, II and III) based on the pattern of the fracture lines on the midface.[2]

A fracture is classified as LeFort I when it extends posteriorly, on a horizontal plane from the pyriform aperture through the zygomaticoalveolar crest to maxillary tuberosities into the pterygopalatine fossa. This type of fracture separates the hard palate and alveolar process from the facial skull.[2]

LeFort II fractures are pyramidal in shape. It extends from the nasofrontal suture to the frontomaxillary suture, through the orbital floor and maxillary sinus, extending inferiorly to the zygomaticoalveolar crest bilaterally. Inferiorly, proceeds caudally to the maxillary tuberosities into the pterygoid process. Superiorly, the fractures extend caudally sectioning through the nasal septum. This fracture dissociates the nasal bones, the nasal septum, and maxilla from the cranial skull and the lateral midface.[2]

LeFort III fractures extend from the nasofrontal suture down through the medial wall and orbital floor to the inferior orbital fissure. It proceeds laterally, interrupts the zygomaticofrontal suture and continues inferiorly through the zygomatic arches bilaterally. From the nasofrontal suture, it extends caudally through the ethmoid and perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, fracturing the pterygoid process and vomer, terminating in the palatine fossa. This fracture completely separates the facial skeleton from the cranial skull.[2]

Figure

The Maxillae; Upper jaw, Left maxilla; Outer surface Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

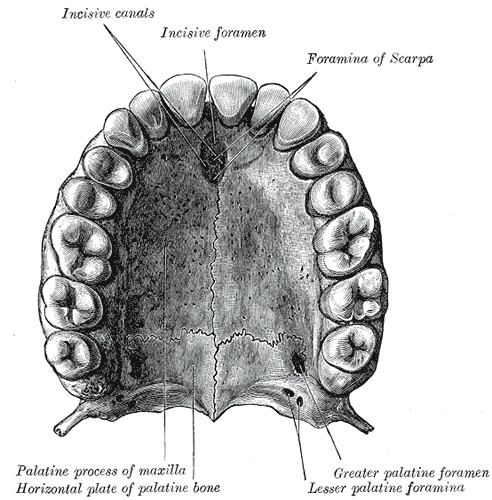

Figure

The Maxilla, The bony palate and alveolar arch Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure

Anterior surface of maxilla at birth Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

- 1.

- Dalgorf D, Higgins K. Reconstruction of the midface and maxilla. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 Aug;16(4):303-11. [PubMed: 18626247]

- 2.

- Kühnel TS, Reichert TE. Trauma of the midface. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;14:Doc06. [PMC free article: PMC4702055] [PubMed: 26770280]

- 3.

- Okay DJ, Genden E, Buchbinder D, Urken M. Prosthodontic guidelines for surgical reconstruction of the maxilla: a classification system of defects. J Prosthet Dent. 2001 Oct;86(4):352-63. [PubMed: 11677528]

- 4.

- Saffar JL, Lasfargues JJ, Cherruau M. Alveolar bone and the alveolar process: the socket that is never stable. Periodontol 2000. 1997 Feb;13:76-90. [PubMed: 9567924]

- 5.

- Sadrameli M, Mupparapu M. Oral and Maxillofacial Anatomy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2018 Jan;56(1):13-29. [PubMed: 29157543]

- 6.

- Lake S, Iwanaga J, Kikuta S, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. The Incisive Canal: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2018 Jul 30;10(7):e3069. [PMC free article: PMC6166911] [PubMed: 30280065]

- 7.

- Bentsianov B, Blitzer A. Facial anatomy. Clin Dermatol. 2004 Jan-Feb;22(1):3-13. [PubMed: 15158538]

- 8.

- Danesh-Sani SA, Loomer PM, Wallace SS. A comprehensive clinical review of maxillary sinus floor elevation: anatomy, techniques, biomaterials and complications. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Sep;54(7):724-30. [PubMed: 27235382]

- 9.

- Ogle OE, Weinstock RJ, Friedman E. Surgical anatomy of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012 May;24(2):155-66, vii. [PubMed: 22386856]

- 10.

- Haghnegahdar A, Khojastepour L, Naderi A. Evaluation of Infraorbital Canal in Cone Beam Computed Tomography of Maxillary Sinus. J Dent (Shiraz). 2018 Mar;19(1):41-47. [PMC free article: PMC5817342] [PubMed: 29492415]

- 11.

- Wilson DB. Embryonic development of the head and neck: Part 3, The face. Head Neck Surg. 1979 Nov-Dec;2(2):145-53. [PubMed: 264107]

- 12.

- Trevizan M, Consolaro A. Premaxilla: an independent bone that can base therapeutics for middle third growth! Dental Press J Orthod. 2017 Mar-Apr;22(2):21-26. [PMC free article: PMC5484266] [PubMed: 28658352]

- 13.

- Baxter DJ, Shroff MM. Developmental maxillofacial anomalies. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2011 Dec;32(6):555-68. [PubMed: 22108218]

- 14.

- Mossey PA, Little J, Munger RG, Dixon MJ, Shaw WC. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. 2009 Nov 21;374(9703):1773-85. [PubMed: 19747722]

- 15.

- Shkoukani MA, Lawrence LA, Liebertz DJ, Svider PF. Cleft palate: a clinical review. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2014 Dec;102(4):333-42. [PubMed: 25504820]

- 16.

- Alvernia JE, Hidalgo J, Sindou MP, Washington C, Luzardo G, Perkins E, Nader R, Mertens P. The maxillary artery and its variants: an anatomical study with neurosurgical applications. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017 Apr;159(4):655-664. [PubMed: 28191601]

- 17.

- Tanoue S, Kiyosue H, Mori H, Hori Y, Okahara M, Sagara Y. Maxillary artery: functional and imaging anatomy for safe and effective transcatheter treatment. Radiographics. 2013 Nov-Dec;33(7):e209-24. [PubMed: 24224604]

- 18.

- Otake I, Kageyama I, Mataga I. Clinical anatomy of the maxillary artery. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2011 Feb;87(4):155-64. [PubMed: 21516980]

- 19.

- Walker HK. Cranial Nerve V: The Trigeminal Nerve. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworths; Boston: 1990. [PubMed: 21250225]

- 20.

- McKay GS. Commentary on paper: "A review of the mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies and their clinical relevance". Arch Oral Biol. 2012 Apr;57(4):321-2. [PubMed: 22192853]

- 21.

- Rodella LF, Buffoli B, Labanca M, Rezzani R. A review of the mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies and their clinical relevance. Arch Oral Biol. 2012 Apr;57(4):323-34. [PubMed: 21996489]

- 22.

- Snider CC, Amalfi AN, Hutchinson LE, Sommer NZ. New Insights into the Anatomy of the Midface Musculature and its Implications on the Nasolabial Fold. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017 Oct;41(5):1083-1090. [PubMed: 28508263]

- 23.

- Datta RK, Viswanatha B, Shree Harsha M. Caldwell Luc Surgery: Revisited. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Mar;68(1):90-3. [PMC free article: PMC4809813] [PubMed: 27066419]

- 24.

- Boeve K, Schepman KP, Vegt BV, Schuuring E, Roodenburg JL, Brouwers AH, Witjes MJ. Lymphatic drainage patterns of oral maxillary tumors: Approachable locations of sentinel lymph nodes mainly at the cervical neck level. Head Neck. 2017 Mar;39(3):486-491. [PubMed: 28006085]

Disclosure: Roberto Soriano declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Joe M Das declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Authors

Roberto M. Soriano1; Joe M Das2.Affiliations

Publication History

Last Update: September 12, 2022.

Copyright

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Publisher

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

NLM Citation

Soriano RM, M Das J. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Maxilla. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.