Continuing Education Activity

Cardiac amyloidosis is one of the leading causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy. It typically presents with rapidly progressive diastolic dysfunction in a non-dilated ventricle. It is one of the under-diagnosed disease entities. The diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis requires a high degree of suspicion, with cardiovascular imaging being pivotal in reaching the diagnosis. This activity reviews the pathophysiology of different types of cardiac amyloidosis and helps decide the treatment modality and determining disease prognosis; it further emphasizes the need for an interprofessional team to diagnose and manage cardiac amyloidosis, including cardiologists, cardiovascular imaging specialists, heart and transplant specialists, and hematologists.

Objectives:

- Describe infiltrative cardiomyopathy and the pathophysiology of cardiac amyloidosis.

- Summarize clinical findings of cardiac amyloidosis, giving examples of different types of cardiac amyloidosis.

- Review the echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) findings of cardiac amyloidosis.

- Explain the management options and their prognosis for different types of cardiac amyloidosis.

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a systemic infiltrative disease characterized by the extracellular deposition of insoluble proteins. The most prevalent variant is amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis, affecting more than ten people per million per year. The protein fibers in the amyloid light chain consist of monoclonal light chains. The other form, amyloid transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis, is characterized by the deposition of a normal or mutated form of transthyretin proteins.[1] Cardiac involvement has been reported in both variants of amyloidosis.

Cardiac amyloidosis is the most common type of restrictive cardiomyopathy, the other two being cardiac sarcoidosis and cardiac hemochromatosis. The infiltrative cardiomyopathies characteristically have a depressed diastolic function in the presence of a non-dilated left ventricle (LV).[2] Irrespective of the etiology, cardiac amyloidosis is the leading cause of mortality in patients with systemic amyloidosis.[3]

Cardiac amyloidosis may manifest primarily or be discovered incidentally in patients with other signs and symptoms of systemic amyloidosis. Delay in diagnosis is common and may lead to a delay in the initiation of the treatment.[4] Cardiac involvement in systemic amyloidosis carries prognostic value and is the most critical determinant of survival in this disease.[5]

Etiology

Cardiac amyloidosis occurs due to the extracellular deposition of a toxic component called amyloid. The amyloid refers to an amalgam of abnormally folded proteins and other matrix-forming components such as proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, collagen, and laminin. The abnormally folded proteins derive from two sources: amyloid light (AL) chain proteins and amyloid transthyretin (ATTR).[6]

Microscopically, the amyloid fibrils are seen as non-branching structures measuring 7-10 nm in diameter. Deposition of these fibrils in the extracellular space leads to the stiffening of the myocardium and depressed cardiac function. This deposition primarily affects diastolic function until late in the disease when left ventricle systolic function also gets affected.[6]

Following are the various etiological types of cardiac amyloidosis:[3]

- Primary amyloidosis (also known as amyloid light chain amyloidosis) – AL amyloidosis - is caused by the deposition of AL fibrils produced by abnormal plasma cells in patients with plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma.

- Secondary amyloidosis – AA amyloidosis – is caused by the deposition of serum amyloid A, which is an inflammatory protein produced in conditions with chronic inflammation.

- Senile systemic amyloidosis (also called wild transthyretin) – ATTRw – is caused by age-related amyloid deposition, which is made from normal TTR (transport-thyroxine-and-retinol) protein. This is the most common type of cardiac amyloidosis.

- Familial amyloidosis – ATTRm - is caused by mutant TTR.

- Isolated atrial amyloidosis – is caused by the deposition of amyloid made from the atrial natriuretic peptide.

Epidemiology

Overall, cardiac amyloidosis is a rare disorder. The prevalence varies with the etiological type. About 10% of multiple myeloma cases may have AL amyloidosis, and 50 to 70% of these may have cardiac involvement. The annual incidence of AL amyloidosis is 1 per 100,000.[6]

With more than 100 TTR genes responsible for the disease, the exact prevalence of familial (hereditary) amyloidosis is unknown. According to one study, the prevalence of one of the TTR genes V122I was 0.0173 in an African American cohort of 14 333.[7]

Senile amyloidosis is the most prevalent type of cardiac amyloidosis, with an estimated prevalence of >10% in patients aged over 60 years being frequently diagnosed as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). At least 10% of patients with aortic stenosis may have ATTRw amyloidosis, and at least 10 to 15% of patients aged >65 years with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction may have cardiac amyloidosis.[8]

With improved survival and diagnostic rates, the prevalence of cardiac amyloidosis is higher than previously estimated. Over 12 years, the prevalence rate has increased from 8 to 17 per 100,000 person-years.[9]

Pathophysiology

The deposition of amyloid can lead to heart diseases in multiple ways. Direct interstitial infiltration leads to increased ventricular wall thickness, ventricular stiffness, and consequent ventricular diastolic dysfunction. In AL amyloidosis, amyloid can get deposited in arterioles leading to angina or, rarely, myocardial infarction. Amyloid infiltration in atria can lead to atrial interstitial changes, establishing a structural substrate for atrial fibrillation. Even in the absence of atrial fibrillation, atrial amyloidosis increases the risk of atrial thrombosis and thromboembolism. Light chains can also cause direct injury to the myocardial cells via reactive oxygen species.

In AL amyloidosis, amyloid fibrils are made from abnormal light chains produced by plasma cells. Transthyretin amyloidosis is caused by the deposition of oligomers and monomers produced by damage to transthyretin tetramer, either due to aging or by a mutation.[6] The isolated atrial amyloidosis is caused by amyloid made from the atrial natriuretic peptide.

History and Physical

Patients with amyloidosis may present with primary cardiac symptoms, or cardiac amyloidosis may be diagnosed incidentally in patients undergoing evaluation for other systemic involvements.

Primary cardiac manifestations can be dyspnea on exertion, palpitations, chest pain, presyncope, and syncope. The patient may have florid heart failure symptoms such as dyspnea at rest, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, lower limb swelling, and abdominal distension due to ascites.

Patients can also have symptoms of other systemic involvement such as dyspepsia, nausea, constipation, early satiety from gastrointestinal involvement, tongue enlargement, bilateral periorbital discoloration, or symptoms of any neuropathy such as carpal tunnel syndrome or erectile dysfunction.

On physical examination, the patient may have periorbital purpura, pedal edema, raised jugular venous pressure (JVP), ascites, fine lung crackles, macroglossia, neuropathy, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The periorbital purpura and macroglossia are pathognomic for cardiac amyloidosis.[10]

Evaluation

Evaluation: Cardiac amyloidosis is an underdiagnosed disease entity. Its systemic manifestations and variety of symptoms based on etiological type make it under-recognized. However, patients with cardiac amyloidosis have the following specific set of findings on cardiovascular investigations.

Electrocardiogram: The 12-lead EKG may show a pseudo-infarction pattern. There can be low voltages in limb leads and Q waves in anterior and inferior leads. (Figure 1). The EKG may also show varying degrees of atrioventricular (AV) block, more commonly, first-degree AV block. These EKG findings are more common in AL amyloidosis. Patients with TTR amyloidosis are more likely to have left bundle branch block (LBBB), a more advanced degree of AV block, and more often normal limb-lead voltages with non-specific ST-T segment changes. Atrial fibrillation is frequently present.[11]

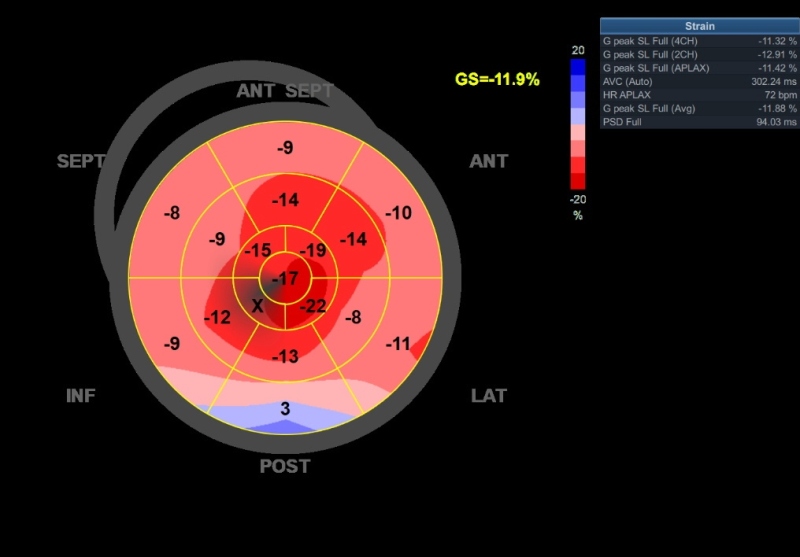

Echocardiography: Usually, an echocardiogram gives the first clue and is pivotal in screening and diagnosing cardiac amyloidosis. The echocardiogram characteristically shows increased myocardial wall thickness and a sparkling appearance of the myocardium (Figure 2).[12]Generally, bi-atrial enlargement is universally present. The LV is non-dilated, and LV systolic function is preserved until late in the disease course. Diastolic dysfunction is also universally present. Typically, there is a rapid progression in the grade of diastolic dysfunction. Frequently, there is pericardial and pleural effusion.The global longitudinal strain (GLS) shows a reduced longitudinal strain from base-apex and well-preserved apical strain giving the classic ‘cherry on top’ appearance, pathognomic of cardiac amyloidosis (Figure 3). The ratio of apical strain to the basal-mid average strain of more than 1.1 carries a high sensitivity and specificity for cardiac amyloidosis.[13]A clinical history of syncope/presyncope, angina or heart failure, left ventricle hypertrophy (LVH) with a bright appearance of myocardium on echo, discordance between the EKG voltage and LVH on the echocardiogram, and the typical apical sparing longitudinal strain suggests the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. There are a few differences in the echocardiographic assessment of TTR and AL amyloidosis. LV is symmetrically hypertrophied with AL but asymmetrically hypertrophied in TTR amyloidosis, giving the appearance of a sigmoid septum. TTR amyloidosis causes more decline in LV systolic and diastolic function than AL amyloidosis. It also causes a greater increase in LV and RV masses.[14]

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: CMR has evolved as a key test in diagnosing cardiac amyloidosis. It helps differentiate amyloidosis from hypertensive heart disease and sarcoidosis. Additionally, it provides information about tissue characterization and helps detect early cardiac amyloidosis. However, it cannot differentiate between TTR and AL amyloidosis. Characteristic findings include restrictive morphology and diastolic dysfunction with disproportionate bi-atrial enlargement and increased myocardial mass and thickening. On late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), there is reduced systolic thickening of LGE segments, and characteristically, there is diffuse circumferential subendocardial LGE which is not restricted to any coronary artery territory. In advanced disease, LGE can be transmurally present. Because of the extracellular deposition of amyloid, there is an increase in T1 (longitudinal relaxation time) and extracellular volume fraction.[15][16]The scan is negative for myocardial edema, and there is rapid gadolinium washout from the LV blood pool. Characteristically, there is difficulty in nulling the normal myocardium on TI mapping. Normally, the LV blood pool nulls before the myocardium. However, this sequence is reversed in amyloidosis, and the myocardium is nulled before the LV blood pool.[15]

Nuclear SPECT: A strongly positive bone tracer cardiac scintigraphy (cardiac uptake greater than bone- stage two or three or bone to the chest wall uptake ratio of >1.5 at one-hour), the echocardiographic features consistent with cardiac amyloidosis, and the absence of systemic signs and symptoms of multiple myeloma are almost diagnostic of TTR amyloidosis. On the other hand, there is poor or no radioisotope uptake in AL amyloidosis.[17]

Endomyocardial biopsy: Biopsy is the gold-standard test for diagnosing cardiac amyloidosis. The biopsy shows characteristic salmon-colored amyloid fibrils on the ‘Congo-red’ stain. On electron microscopy, there is a characteristic ‘apple-green’ birefringence on polarized light. A cardiac biopsy is an invasive test and carries a sensitivity of 87 to 98%.[18]

Genotyping: Genotyping is important in patients with ATTR amyloidosis. More than 120 gene variants have been identified to cause cardiac amyloidosis. The two most common variants are Thr60Ala and Val122lle. Genotyping is essential to predict treatment response and prognosis. The type of variants depends on geographical location and ethnic variation.[19]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of cardiac amyloidosis aims to treat the underlying cause and the symptoms of heart failure.

- Treatment of heart failure: For AL amyloidosis, diuretics are the cornerstone of therapy. Most patients do not tolerate renin-angiotensin-aldosterone inhibitors (RAAS-I), with hypotension being precipitated even with low doses. However, RAAS-I is better tolerated in ATTR amyloidosis. Orthostatic hypotension is commonly encountered due to autonomic dysfunction. Peripheral vasoconstrictors such as midodrine can be used to maintain blood pressure while allowing diuresis to relieve congestion. Likewise, beta-blockers are poorly tolerated. Profound hypotension on initiation of low doses of beta-blockers should raise suspicion for the possibility of underlying cardiac amyloidosis. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and loop diuretics, hence, remain the vital therapy options for heart failure management in cardiac amyloidosis.

- Treatment of AL amyloidosis is based on standard treatment for multiple myeloma. It requires coordinated teamwork of hematologists and cardiologists. The aim is to remove paraproteins from blood and urine and stabilize bone marrow. The most used chemotherapy agents include melphalan (an alkylating agent) and bortezomib (proteasome inhibitor). Bortezomib can be used along with dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide. A positive cardiac response is defined as a 30% reduction in B-natriuretic peptides over six months.

- Orthotropic heart transplant in AL amyloidosis is associated with a high risk of disease recurrence in the transplanted heart. However, in carefully selected patients (particularly those with clinically isolated heart involvement), a heart transplant can be considered if the patient agrees to undergo intensive chemotherapy for plasma cells after the heart transplant. This is because the amyloid heart cannot tolerate aggressive chemotherapy because of depressed myocardial function. Hence, a heart transplant followed by aggressive chemotherapy can be attempted with an expected 5-year survival of 60%.

- Patients with wild-ATTR amyloidosis usually have isolated heart involvement, making them suitable candidates for heart transplants. However, because of the greater age of diagnosis (7 decades or later), most patients are excluded owing to their age.

- Transthyretin is mainly produced in the liver. In mutant ATTR, liver transplantation is necessary to remove the source of amyloid proteins. Orthotropic liver transplant carries a 5-year survival of 75% (mainly for Val30Met mutation). Patients with mutant-ATTR are younger than wild-ATTR patients. These patients are suitable for a heart transplant in isolated heart involvement. However, if there is autonomic neuropathy, most patients would require combined liver and heart transplants to prevent the recurrence of amyloid disease in the transplanted heart.

- However, in wild ATTR, there is no role in liver transplantation. Instead, some agents (under investigation) can be used to stabilize TTR, such as tafamidis.

- Rhythm and rate control for atrial arrhythmias is challenging in amyloidosis as beta-blockers are poorly tolerated. Amiodarone remains a reasonable option and is well tolerated. Digoxin tends to bind to amyloid fibrils and increases the risk of digoxin toxicity. However, digoxin can be used for rate control in patients with cardiac amyloidosis and atrial fibrillation if carefully titrated. Calcium channel blockers have not been proven to be of benefit in amyloid diastolic dysfunction as with other diastolic dysfunctions such as hypertensive heart disease and may precipitate hypotension. For atrial flutter, catheter ablation can be attempted. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in the setting of amyloidosis carries a high recurrence rate. Patients may irrespectively require anticoagulation because of the increased risk of thrombosis and thromboembolism.

- In the case of atrioventricular block, one should aim for biventricular pacing as the pacing of the right ventricle alone in the setting of stiff myocardium would be disadvantageous. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention provides no clear benefit and is not indicated. It is reserved for secondary prevention, as otherwise generally indicated.

- Treatment of secondary amyloidosis requires treatment of the underlying inflammatory conditions.

- Isolated atrial amyloidosis generally requires no treatment.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

Essentially, any restrictive cardiomyopathy can be mistaken for this disease. Common features of restrictive cardiomyopathies include dyspnea in the presence of normal ejection fraction, diastolic dysfunction, and biatrial enlargement. Restrictive cardiomyopathies include cardiac sarcoidosis, glycogen storage diseases, and hemochromatosis. The differentials also include other causes of similar echocardiographic appearance, such as hypertensive heart disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Prognosis

The prognosis is variable and depends on the type of cardiac amyloidosis. The average survival time in untreated patients is as follows: AL (primary) 9 to 24 months, ATTR familial 7 to 10 years, senile amyloidosis 5 to 7 years, AA (secondary) amyloidosis more than ten years.

Overall, ATTR amyloidosis has a better prognosis than AL amyloidosis. ATTR amyloidosis progresses slowly and has a late presentation (average decade of presentation of 7). The 4-year survival of AL amyloidosis in patients treated with stem-cell transplantation is more than 90%. Patients with cardiac involvement undergoing stem cell transplants have a median survival of more than 10-year. The median survival in AL amyloidosis is 10-years, except for those with advanced-stage diseases, who carry a 50% one-year survival.

Mutant ATTR has an overall four-year survival of 16%. The survival of mutant ATTR depends on the type of mutation. The Val30Met is the most common mutation in mutant ATTR with an overall prognosis of 79%, whereas the Val122Ile mutation carries a four-year prognosis of 40%.[20]

Complications

Complications of cardiac amyloidosis are mainly due to structural abnormalities potentiating chances of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular arrhythmias.[3] As a result, a patient's course can be complicated by:

- Atrial fibrillation – can lead to thromboembolism and heart failure.

- Diastolic dysfunction - heart failure. Increased mortality. Increased arrhythmogenesis.

- Heart failure hospitalizations and mortality.

- Ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac conduction abnormalities.

- Autonomic neuropathy - in systemic involvement.

- Tendinopathies - in systemic involvement.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Cardiac amyloidosis has a variable prognosis. The treatment modalities differ with the etiological type. Understanding the disease course is vital on the patient's end. The patient needs to be aware of the systemic nature of the disease involvement.

The patient must understand the need for a multidisciplinary team required for the treatment, including a cardiologist, hematologist, gastroenterologist, and transplant specialist. Treatment of heart failure in cardiac amyloidosis differs from the standard guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure. Patients are usually sensitive even to the smallest possible doses, making a very slow titration necessary. This means a more generous follow-up schedule than heart failure due to other causes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Early diagnosis is the key to determining prognosis. A high degree of suspicion based on the clinical history and laboratory investigations can lead to earlier diagnosis and quicker initiation of therapy. Management of cardiac amyloidosis requires a multidisciplinary team. Clinical consultation with a cardiologist and active input of a hematologist is necessary to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment. Moreover, the cardiac amyloidosis team requires liver and heart transplant specialist input.

An individualized approach must be used to decide the extent of treatment for every patient. It also requires the expertise of an imaging specialist. However, endomyocardial biopsy is the gold standard but is used less often. CMR has evolved as a useful tool in diagnosing cardiac amyloidosis.

References

- 1.

- Nienhuis HL, Bijzet J, Hazenberg BP. The Prevalence and Management of Systemic Amyloidosis in Western Countries. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2016 Apr;2(1):10-9. [PMC free article: PMC4946260] [PubMed: 27536687]

- 2.

- Brown KN, Pendela VS, Ahmed I, Diaz RR. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 30, 2023. Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. [PubMed: 30725919]

- 3.

- Martinez-Naharro A, Hawkins PN, Fontana M. Cardiac amyloidosis. Clin Med (Lond). 2018 Apr 01;18(Suppl 2):s30-s35. [PMC free article: PMC6334035] [PubMed: 29700090]

- 4.

- Ladefoged B, Dybro A, Povlsen JA, Vase H, Clemmensen TS, Poulsen SH. Diagnostic delay in wild type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis - A clinical challenge. Int J Cardiol. 2020 Apr 01;304:138-143. [PubMed: 32033783]

- 5.

- Lei C, Zhu X, Hsi DH, Wang J, Zuo L, Ta S, Yang Q, Xu L, Zhao X, Wang Y, Sun S, Liu L. Predictors of cardiac involvement and survival in patients with primary systemic light-chain amyloidosis: roles of the clinical, chemical, and 3-D speckle tracking echocardiography parameters. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):43. [PMC free article: PMC7819214] [PubMed: 33478398]

- 6.

- Siddiqi OK, Ruberg FL. Cardiac amyloidosis: An update on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018 Jan;28(1):10-21. [PMC free article: PMC5741539] [PubMed: 28739313]

- 7.

- Jacobson DR, Alexander AA, Tagoe C, Buxbaum JN. Prevalence of the amyloidogenic transthyretin (TTR) V122I allele in 14 333 African-Americans. Amyloid. 2015;22(3):171-4. [PubMed: 26123279]

- 8.

- Bajwa F, O'Connor R, Ananthasubramaniam K. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of cardiac amyloidosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2022 Sep;27(5):1471-1484. [PubMed: 34694575]

- 9.

- Gilstrap LG, Dominici F, Wang Y, El-Sady MS, Singh A, Di Carli MF, Falk RH, Dorbala S. Epidemiology of Cardiac Amyloidosis-Associated Heart Failure Hospitalizations Among Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. Circ Heart Fail. 2019 Jun;12(6):e005407. [PMC free article: PMC6557425] [PubMed: 31170802]

- 10.

- Porcari A, Rossi M, Cappelli F, Canepa M, Musumeci B, Cipriani A, Tini G, Barbati G, Varrà GG, Morelli C, Fumagalli C, Zampieri M, Argirò A, Vianello PF, Sessarego E, Russo D, Sinigiani G, De Michieli L, Di Bella G, Autore C, Perfetto F, Rapezzi C, Sinagra G, Merlo M. Incidence and risk factors for pacemaker implantation in light-chain and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022 Jul;24(7):1227-1236. [PubMed: 35509181]

- 11.

- Cheng Z, Zhu K, Tian Z, Zhao D, Cui Q, Fang Q. The findings of electrocardiography in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2013 Mar;18(2):157-62. [PMC free article: PMC6932432] [PubMed: 23530486]

- 12.

- Kiotsekoglou A, Saha SK, Nanda NC, Lindqvist P. Echocardiographic diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis: Does the masquerader require only a "cherry on top"? Echocardiography. 2020 Nov;37(11):1713-1715. [PMC free article: PMC7814664] [PubMed: 33283347]

- 13.

- Maurer MS, Elliott P, Comenzo R, Semigran M, Rapezzi C. Addressing Common Questions Encountered in the Diagnosis and Management of Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circulation. 2017 Apr 04;135(14):1357-1377. [PMC free article: PMC5392416] [PubMed: 28373528]

- 14.

- Boldrini M, Cappelli F, Chacko L, Restrepo-Cordoba MA, Lopez-Sainz A, Giannoni A, Aimo A, Baggiano A, Martinez-Naharro A, Whelan C, Quarta C, Passino C, Castiglione V, Chubuchnyi V, Spini V, Taddei C, Vergaro G, Petrie A, Ruiz-Guerrero L, Moñivas V, Mingo-Santos S, Mirelis JG, Dominguez F, Gonzalez-Lopez E, Perlini S, Pontone G, Gillmore J, Hawkins PN, Garcia-Pavia P, Emdin M, Fontana M. Multiparametric Echocardiography Scores for the Diagnosis of Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Apr;13(4):909-920. [PubMed: 31864973]

- 15.

- Tipoo Sultan FA, Khan MT. Clinical presentation, diagnostic features on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and outcome of patients with cardiac amyloidosis presenting to a tertiary care setting. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021 Dec;71(12):2802-2805. [PubMed: 35150542]

- 16.

- Kwong RY, Falk RH. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2005 Jan 18;111(2):122-4. [PubMed: 15657385]

- 17.

- Li W, Uppal D, Wang YC, Xu X, Kokkinidis DG, Travin MI, Tauras JM. Nuclear Imaging for the Diagnosis of Cardiac Amyloidosis in 2021. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 May 30;11(6) [PMC free article: PMC8228334] [PubMed: 34070853]

- 18.

- Bowen K, Shah N, Lewin M. AL-Amyloidosis Presenting with Negative Congo Red Staining in the Setting of High Clinical Suspicion: A Case Report. Case Rep Nephrol. 2012;2012:593460. [PMC free article: PMC3914171] [PubMed: 24555137]

- 19.

- Maurer MS, Hanna M, Grogan M, Dispenzieri A, Witteles R, Drachman B, Judge DP, Lenihan DJ, Gottlieb SS, Shah SJ, Steidley DE, Ventura H, Murali S, Silver MA, Jacoby D, Fedson S, Hummel SL, Kristen AV, Damy T, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Coelho T, Mundayat R, Suhr OB, Waddington Cruz M, Rapezzi C., THAOS Investigators. Genotype and Phenotype of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis: THAOS (Transthyretin Amyloid Outcome Survey). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jul 12;68(2):161-72. [PMC free article: PMC4940135] [PubMed: 27386769]

- 20.

- Aimo A, Merlo M, Porcari A, Georgiopoulos G, Pagura L, Vergaro G, Sinagra G, Emdin M, Rapezzi C. Redefining the epidemiology of cardiac amyloidosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of screening studies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022 Dec;24(12):2342-2351. [PMC free article: PMC10084346] [PubMed: 35509173]

Disclosure: Pirbhat Shams declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Intisar Ahmed declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Authors

Pirbhat Shams1; Intisar Ahmed2.Affiliations

Publication History

Last Update: July 30, 2023.

Copyright

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Publisher

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

NLM Citation

Shams P, Ahmed I. Cardiac Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.