Introduction

Bone conduction (BC) refers to the phenomenon in which vibrations are transmitted through the bones of the skull to the cochlea and the associated sensorineural structures resulting in the perception of sound. Bone conduction is in contrast to the route of sound transmission known as air conduction (AC), in which sound is transmitted in the air through the ear canal to the ossicles of the middle ear (malleus, incus, stapes) via the tympanic membrane, thus stimulating the sensorineural organs of the inner ear.[1]

Multiple mechanisms are involved in bone conduction sound transmission, including the inertial force affecting cochlear fluids and middle ear ossicles, pressure changes in the ear canal, and pressure changes transmitted through a third window of the cochlea (which is a pathologic, abnormal structure).[2] Ultimately, both AC and bone conduction cause a vibration of the cochlea's basilar membrane, a structure attached medially to the osseous spiral lamina, resulting in stimulation of the cochlear nerve.[3] Methods for testing BC have existed since the 19th century. Early methods involved tuning forks and including the Weber and Rinne tests, which are still used today.[4]

Modern bone conduction evaluation is frequently performed as a component of audiometry testing, especially when it is clinically useful to distinguish between sensorineural and conductive hearing loss. Bone conduction evaluation methods involve using specialized equipment, including an oscillator to produce vibrations at predetermined frequencies and amplitudes.[5]

Procedures

Tuning Fork Tests

The Rinne and Weber tests are designed to stimulate bone conduction and are used as a part of the initial evaluation of hearing loss. They are screening tests and are not considered to replace formal audiometry.[6] These tests are performed using a tuning fork with a frequency of 256 Hz, 512 Hz, or 1024 Hz, with 512 Hz being the most commonly used frequency; 128 Hz tuning forks are not used for the Rinne and Weber tests but are instead used in neurological evaluations.[7]

The Weber test is performed by placing the vibrating tuning fork equidistant from both ears on either the vertex, forehead, bridge of the nose, or chin and asking the patient if the sound is heard loudest in one ear or equally in both ears.[8] In patients with normal hearing or symmetrical conductive hearing loss, the Weber test does not demonstrate lateralization (i.e., the sound of the tuning fork is heard equally in both ears). In patients with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, the Weber test lateralizes to the unaffected ear (i.e., the sound of the tuning fork is heard louder in the better ear). In patients with unilateral conductive hearing loss, the Weber test lateralizes to the affected ear (i.e., the sound of the tuning fork will be heard in the worse ear).

The Rinne test differentiates between sound transmission by AC and sound transmission by bone conduction. The Rinne test is performed by placing the vibrating tuning fork onto the mastoid process and then asking the patient to report when they can no longer hear the sound. Once the patient can no longer hear the sound, the vibrating tuning fork is immediately moved adjacent to the ear canal about 3 cm from the ear, and the patient is again asked to report when they can no longer hear the sound. A normal finding – termed a “positive Rinne test” – indicates AC is perceived more than bone conduction. In this case, the patient can hear the tuning fork adjacent to the ear canal for a longer duration than when they heard the sound over their mastoid process. An abnormal finding of the Rinne test – termed a “negative Rinne test” – suggests BC is perceived more than AC. In this case, the patient cannot hear or can only faintly hear the tuning fork after it is moved from the mastoid process to the air adjacent to the ear canal.[9]

Pure Tone Audiometry

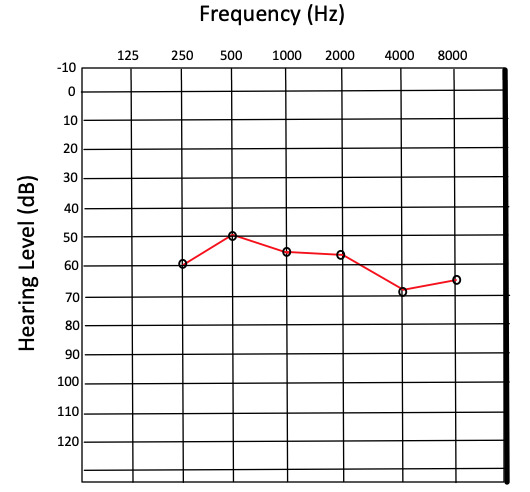

Pure tone audiometry (PTA) is performed by producing a tone with a controlled frequency and recording the lowest sound intensity in decibels (dB) at which the tone can be perceived half of the time. This value is referred to as the threshold and is used to compare a patient’s hearing acuity with that of an average population. Thresholds are measured for a set of frequencies, typically ranging from 250 to 8000 hertz (Hz). The results are recorded on a graph known as an audiogram, which ordinarily displays hearing threshold level on the y-axis and frequency on the x-axis (see figure).[10]

Although audiometry is sometimes performed solely using earphones, which rely largely on AC, bone conduction can also be evaluated during audiometry and is an essential component of a true comprehensive audiogram. This is accomplished by positioning an oscillator on the patient’s mastoid process and measuring threshold values for the same frequencies used in AC testing. In this manner, bone conduction can be compared with AC graphically, illustrating what is referred to as an air-bone gap to document differences in AC vs. BC. Frequently, results from the right ear are plotted as an “O” for AC thresholds and an “<” for BC thresholds, while results from the left ear are plotted as an “X” for AC thresholds and an “>” for BC thresholds.[11]

Often, the non-test ear is intentionally exposed to a masking frequency that is out of phase from the tone generated by the oscillator in the test ear, thus creating a noise-canceling effect. This masking technique is intended to prevent the sound of the oscillator from being perceived by the non-test ear, which would skew test results, especially if the non-test ear has better acuity – and thus a lower threshold – at certain frequencies than the test ear.[12]

Auditory Brainstem Response

PTA is referred to as a behavioral hearing test because it is based on the subjective perception of tones reported by the patient. Auditory brainstem response (ABR), also referred to as brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEP), on the other hand, is a method that relies solely on objective measures to evaluate the function of auditory pathways to the level of the mesencephalon of the brainstem.[13] ABR testing was developed in the 1970s and is principally used to diagnose and study sensorineural patterns of hearing loss.[14]

Electrical signals produced by hair cell vibration ascend to the auditory cortex via several nuclei, including first the cochlear nuclei, then the medial geniculate nuclei, lateral lemniscus, inferior colliculi, and superior olivary complex. Potentials generated by these signals are recorded by electrodes placed on the surface of the scalp, ears, and forehead.[15] The readings in ABR testing consist of a series of positive wave peaks with negative troughs between them. These peaks are labeled I-VII and normally correspond with a detected stimulus in the brainstem nuclei 10 milliseconds after a test sound is produced. From this data, predicted thresholds can be calculated and compared at varying frequencies similar to PTA.[16]

As an objective testing method, ABR testing has the advantage of being useful in evaluating hearing in infants, young children, and other patients with limited ability to communicate. As with PTA, ABR testing is usually performed with earphones, thus involving AC through the transformation of mechanical vibration in the ear canal into bioelectrical signals via cochlear hair cells. However, because both AC and bone conduction result in stimulation of the cochlear nerve (cranial nerve VIII), BC can also be evaluated in the stimulation of ABR. Evaluating bone conduction in this manner is accomplished by using an oscillator in contact with the mastoid process or other bony structures of the skull.[17] In comparing PTA with ABR testing in the context of BC stimulation, a difference in threshold level of 18 to 28 dB (decibels) can be expected in individuals with normal hearing, with ABR registering at a higher threshold than PTA.[18][19]

Indications

While the Rinne and Weber tuning fork tests can be useful in preliminary evaluation of hearing loss, they are not usually performed as standalone tests due to variable reports of sensitivity and specificity and limited diagnostic utility in quantifying the degree of any hearing loss detected.[20]

Tuning fork tests are a helpful clinical tool due to their convenience and ease of use, but audiometry is the gold standard for formal hearing loss evaluation. For this reason, tuning fork tests are mainly indicated in the setting of suspected hearing loss in a communicative patient as an initial clinical workup to guide further auditory testing or in certain post-operative situations to confirm patent auditory neural pathways.[21]

An indication for PTA is suspected hearing loss in a patient who can participate in behavioral hearing testing. However, according to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, PTA is not recommended as a screening protocol for asymptomatic adult patients due to insufficient evidence to assess the harms and benefits of screening.[22]

In contrast, ABR testing as part of newborn hearing screening is universally recommended. It is important for early diagnosis of and intervention in a number of treatable causes of hearing loss to encourage proper language development as the child grows.[23] Testing ABR by BC stimulation is beneficial for differentiating between sensorineural and conductive hearing loss in infants with suspected or diagnosed hearing loss.[24]

Potential Diagnosis

Hearing loss is generally categorized as sensorineural, conductive, or mixed. Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) occurs with dysfunction within either the cochlea or any component of the neural pathways leading to and including the auditory cortex. Conductive hearing loss occurs due to disruption of sound conduction through the middle ear, the external ear, or both. Mixed hearing loss occurs due to both SNHL and conductive hearing loss.[25]

Bone conduction evaluation is useful in differentiating between these three categories of hearing loss in patients whose diagnoses are uncertain, who require assessment of treatment progression, or who are predisposed to developing hearing loss and thus require periodic screening. Appropriate BC evaluation methods (PTA, ABR, or tuning fork tests) vary depending on the patient’s age and ability to communicate, as well as the suspected mechanism of hearing loss and degree of diagnostic certainty required. Of note, some diagnoses may require further tests, including tympanometry, computed tomography, and otoacoustic emissions, none of which directly involve BC evaluation.[26]

Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Common causes of SNHL include:[27][28]

- Presbycusis

- Chronic metabolic and autoimmune conditions - e.g., diabetes

- Infection - e.g., meningitis, viral encephalitis

- Syndromic and nonsyndromic congenital disorders

- Ototoxic medications - e.g., platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents, loop diuretics, aminoglycoside antibiotics

- Neoplasm - e.g., vestibular schwannoma

- Head trauma

- Noise-induced hearing loss

Conductive Hearing Loss

Common causes of conductive hearing loss include:[29][30][31][32]

- Congenital anatomic abnormalities - i.e., defects occurring anywhere from the pinna to the footplate of the stapes

- Cholesteatoma

- Obstruction - e.g., earwax, foreign body

- Tympanic membrane perforation - e.g., barotrauma

- Acute otitis media

- Otitis media with effusion

- Scarring of the middle ear - often related to recurrent infection or trauma

- Otosclerosis

- Ossicular discontinuity

- Neoplasm

Normal and Critical Findings

For results and interpretation of tuning fork tests, see the “Procedures” section. Notably, tuning fork tests are no longer used as definitive diagnostic tools. Instead, tuning fork tests are considered a convenient preliminary clinical test.[6] A normal finding in ABR testing with BC stimulation is regarded as thresholds of approximately 0 to 15 dB in infants. A normal finding in PTA with BC stimulation is thresholds of 0 to 25 dB in adults. Degrees of hearing impairment are classified by ranges of hearing thresholds above these values. According to the WHO’s Grades of Hearing Impairment, thresholds are categorized as slight (26 to 40 dB), moderate (41 to 60 dB), severe (61 to 80 dB), and profound (>80 dB) impairment.[33]

Specific patterns on audiograms can be recognized as indicative of particular causes of hearing loss. It is often diagnostically beneficial to distinguish between SNHL, conductive hearing loss, and mixed hearing loss by calculating air-bone gaps. For instance, in patients with tympanic membrane perforation, an air-bone gap is often measurable, especially at lower frequencies. This finding indicates that BC is better than AC at those frequencies, as would be expected in a patient whose tympanic membrane is not functionally contributing to conductive hearing due to injury.[34]

Another example of a critical finding on audiogram includes bilateral downward sloping high-frequency threshold increases with no significant air-bone gap, which is consistent with presbycusis, a leading cause of SNHL. This finding is due to selective high-frequency hearing loss in the aging inner ear.[35]

In patients with bilateral noise-induced SNHL, as is often observed in patients who work in loud environments without adequate hearing protection, there is no significant air-bone gap, and a threshold increase spanning from approximately 3,000 Hz to 4,000 Hz is characteristically observed. A final critical finding includes a large unilateral increase in thresholds centered at approximately 1,000 Hz with no air-bone gap. This finding is consistent with unilateral SNHL, which often requires further workup to rule out causes such as a vestibular schwannoma or other mass-occupying lesions.[36] ABR testing may provide additional diagnostic information relating to retrocochlear causes of unilateral SNHL, though the gold standard in this situation is magnetic resonance imaging.[37]

Interfering Factors

Factors which may interfere with the successful and accurate evaluation of bone conduction are numerous and complex. Some evidence suggests that air-bone gaps obtained by manual (also known as traditional) PTA methods are more susceptible to tester bias effects when compared to those obtained via automated PTA methods. This evidence is based on large datasets showing lower air-bone gap variability in manual versus automated PTA. It is hypothesized to be associated with prior knowledge of hearing loss characteristics.[38]

Other studies suggest that manual and automated PTA methods produce sufficiently similar results, indicating that either method is acceptable provided their calculated threshold differences fall within approximately 5 dB of each other.[39][40]

It has been hypothesized that frequencies above 4,000 Hz are prone to error from false air-bone gaps during PTA. [41] Occlusion of the ear canal during BC evaluation does not appear to have a significant corrective effect on these false air-bone gaps.[42] However, several studies have suggested that adjusting the reference equivalent threshold force level, a value used in determining BC thresholds, by approximately 14 dB proves to be effective at correcting for false air-bone gaps at these frequencies.[43]

Patient Safety and Education

To ensure accurate assessment and treatment of hearing loss, patients must be evaluated by trained professionals. Hearing loss can vary in presentation depending on social and environmental factors, and thus a thorough history is warranted in the evaluation of hearing. Patients regularly exposed to loud occupational and recreational noise may benefit from undergoing audiometric screening (often mandated annually for workplace-related noise exposure) in addition to the use of effective ear protection.[44][45]

Some studies suggest that before undergoing PTA, patients should avoid exposure to loud noises (including those louder than a household vacuum cleaner) for at least 14 hours to prevent temporary threshold shifts, which may confound test results. Parents and caretakers of pediatric patients should be educated on the necessity of newborn hearing screening and at well-child visits. Effective follow-up is vital in the early detection and treatment of pediatric hearing loss.[46]

Regarding BC evaluation specifically, patients, especially children, should be made aware that the vibration of an oscillator is nonpainful and will not cause harm despite an unusual sensation. With the increasing use of bone conduction hearing devices, patients with hearing loss should be sufficiently educated on the results of their audiometric testing and counseled in choosing an appropriate amplification device.[47]

Clinical Significance

Evaluation of bone conduction is useful as a component of audiometry in a variety of patient populations and clinical settings. Screening for hearing loss using audiometry in preschool and school-age children is an accurate and beneficial tool for guiding early diagnosis and intervention.[48] Notably, bone conduction evaluation is an integral factor in the selection and operation of bone conduction hearing devices, which have been shown to significantly improve the quality of life n pediatric patients with a variety of causes of hearing loss.[49][50]

Age-related hearing loss is significantly associated with cognitive impairment and dementia in adults.[51] While the reason for this association remains poorly understood and further research is warranted, the decreasing cost and widespread availability of hearing evaluation and hearing aid devices make them a useful clinical tool for improving the quality of life of older patients with suspected hearing loss.[52]

More broadly, due to the association of hearing loss with increased levels of disease burden and hospitalization in older adults, PTA with AC and BC evaluation can provide clinically relevant information for improving patient outcomes.[53][54]

Figure

Audiogram showing severe hearing loss Contributed by Josiah Brandt.

References

- 1.

- Stenfelt S. Inner ear contribution to bone conduction hearing in the human. Hear Res. 2015 Nov;329:41-51. [PubMed: 25528492]

- 2.

- Stenfelt S. Acoustic and physiologic aspects of bone conduction hearing. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;71:10-21. [PubMed: 21389700]

- 3.

- Dauman R. Bone conduction: an explanation for this phenomenon comprising complex mechanisms. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2013 Sep;130(4):209-13. [PubMed: 23743177]

- 4.

- Reiss M. [Tuning-fork tests--outdated?]. Fortschr Med. 1999 Apr 30;117(12):18-20. [PubMed: 10361362]

- 5.

- Walker JJ, Cleveland LM, Davis JL, Seales JS. Audiometry screening and interpretation. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Jan 01;87(1):41-7. [PubMed: 23317024]

- 6.

- Browning GG, Swan IR. Sensitivity and specificity of Rinne tuning fork test. BMJ. 1988 Nov 26;297(6660):1381-2. [PMC free article: PMC1835056] [PubMed: 3146371]

- 7.

- Wahid NWB, Hogan CJ, Attia M. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jul 10, 2023. Weber Test. [PubMed: 30252391]

- 8.

- Recommended procedure for Rinne and Weber tuning-fork tests. British Society of Audiology. Br J Audiol. 1987 Aug;21(3):229-30. [PubMed: 3620757]

- 9.

- Kong EL, Fowler JB. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jan 30, 2023. Rinne Test. [PubMed: 28613725]

- 10.

- Saunders AZ, Stein AV, Shuster NL. Audiometry. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworths; Boston: 1990. [PubMed: 21250083]

- 11.

- Davies RA. Audiometry and other hearing tests. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;137:157-76. [PubMed: 27638069]

- 12.

- McDermott JC, Fausti SA, Henry JA, Frey RH. Effects of contralateral masking on high-frequency bone-conduction thresholds. Audiology. 1990;29(6):297-303. [PubMed: 2275644]

- 13.

- Bargen GA. Chirp-Evoked Auditory Brainstem Response in Children: A Review. Am J Audiol. 2015 Dec;24(4):573-83. [PubMed: 26649461]

- 14.

- Young A, Cornejo J, Spinner A. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Jan 12, 2023. Auditory Brainstem Response. [PubMed: 33231991]

- 15.

- Felix RA, Gourévitch B, Portfors CV. Subcortical pathways: Towards a better understanding of auditory disorders. Hear Res. 2018 May;362:48-60. [PMC free article: PMC5911198] [PubMed: 29395615]

- 16.

- Biacabe B, Chevallier JM, Avan P, Bonfils P. Functional anatomy of auditory brainstem nuclei: application to the anatomical basis of brainstem auditory evoked potentials. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001 Jan;28(1):85-94. [PubMed: 11137368]

- 17.

- Seo YJ, Kwak C, Kim S, Park YA, Park KH, Han W. Update on Bone-Conduction Auditory Brainstem Responses: A Review. J Audiol Otol. 2018 Apr;22(2):53-58. [PMC free article: PMC5894486] [PubMed: 29471611]

- 18.

- Kim Y, Han W, Park S, You S, Kwak C, Seo Y, Lee J. Better Understanding of Direct Bone-Conduction Measurement: Comparison with Frequency-Specific Bone-Conduction Tones and Brainstem Responses. J Audiol Otol. 2020 Apr;24(2):85-90. [PMC free article: PMC7141994] [PubMed: 31747742]

- 19.

- Muchnik C, Neeman RK, Hildesheimer M. Auditory brainstem response to bone-conducted clicks in adults and infants with normal hearing and conductive hearing loss. Scand Audiol. 1995;24(3):185-91. [PubMed: 8552978]

- 20.

- Kelly EA, Li B, Adams ME. Diagnostic Accuracy of Tuning Fork Tests for Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Aug;159(2):220-230. [PubMed: 29661046]

- 21.

- Bayoumy AB, de Ru JA. Sudden deafness and tuning fork tests: towards optimal utilisation. Pract Neurol. 2020 Feb;20(1):66-68. [PMC free article: PMC7029235] [PubMed: 31444233]

- 22.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Epling JW, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Pbert L, Silverstein M, Stevermer J, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening for Hearing Loss in Older Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021 Mar 23;325(12):1196-1201. [PubMed: 33755083]

- 23.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007 Oct;120(4):898-921. [PubMed: 17908777]

- 24.

- Foxe JJ, Stapells DR. Normal infant and adult auditory brainstem responses to bone-conducted tones. Audiology. 1993;32(2):95-109. [PubMed: 8476354]

- 25.

- Anastasiadou S, Al Khalili Y. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): May 23, 2023. Hearing Loss. [PubMed: 31194463]

- 26.

- Tanna RJ, Lin JW, De Jesus O. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Aug 23, 2023. Sensorineural Hearing Loss. [PubMed: 33351419]

- 27.

- Chau JK, Lin JR, Atashband S, Irvine RA, Westerberg BD. Systematic review of the evidence for the etiology of adult sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2010 May;120(5):1011-21. [PubMed: 20422698]

- 28.

- Kuhn M, Heman-Ackah SE, Shaikh JA, Roehm PC. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a review of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Trends Amplif. 2011 Sep;15(3):91-105. [PMC free article: PMC4040829] [PubMed: 21606048]

- 29.

- Isaacson JE, Vora NM. Differential diagnosis and treatment of hearing loss. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Sep 15;68(6):1125-32. [PubMed: 14524400]

- 30.

- Kuo CL, Shiao AS, Yung M, Sakagami M, Sudhoff H, Wang CH, Hsu CH, Lien CF. Updates and knowledge gaps in cholesteatoma research. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:854024. [PMC free article: PMC4381684] [PubMed: 25866816]

- 31.

- Quesnel AM, Ishai R, McKenna MJ. Otosclerosis: Temporal Bone Pathology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Apr;51(2):291-303. [PubMed: 29397947]

- 32.

- Mills R, Hathorn I. Aetiology and pathology of otitis media with effusion in adult life. J Laryngol Otol. 2016 May;130(5):418-24. [PubMed: 26976514]

- 33.

- Olusanya BO, Davis AC, Hoffman HJ. Hearing loss grades and the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull World Health Organ. 2019 Oct 01;97(10):725-728. [PMC free article: PMC6796665] [PubMed: 31656340]

- 34.

- Orji FT, Agu CC. Patterns of hearing loss in tympanic membrane perforation resulting from physical blow to the ear: a prospective controlled cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009 Dec;34(6):526-32. [PubMed: 20070761]

- 35.

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993 Jan;102(1 Pt 2):1-16. [PubMed: 8420477]

- 36.

- Kim SH, Lee SH, Choi SK, Lim YJ, Na SY, Yeo SG. Audiologic evaluation of vestibular schwannoma and other cerebellopontine angle tumors. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136(2):149-53. [PubMed: 26479426]

- 37.

- Peterein JL, Neely JG. Auditory brainstem response testing in neurodiagnosis: structure versus function. J Am Acad Audiol. 2012 Apr;23(4):269-275. [PubMed: 22463940]

- 38.

- Margolis RH, Wilson RH, Popelka GR, Eikelboom RH, Swanepoel de W, Saly GL. Distribution Characteristics of Air-Bone Gaps: Evidence of Bias in Manual Audiometry. Ear Hear. 2016 Mar-Apr;37(2):177-88. [PMC free article: PMC4767567] [PubMed: 26627469]

- 39.

- Swanepoel de W, Biagio L. Validity of diagnostic computer-based air and forehead bone conduction audiometry. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2011 Apr;8(4):210-4. [PubMed: 21391065]

- 40.

- Shojaeemend H, Ayatollahi H. Automated Audiometry: A Review of the Implementation and Evaluation Methods. Healthc Inform Res. 2018 Oct;24(4):263-275. [PMC free article: PMC6230538] [PubMed: 30443414]

- 41.

- Lightfoot GR, Hughes JB. Bone conduction errors at high frequencies: implications for clinical and medico-legal practice. J Laryngol Otol. 1993 Apr;107(4):305-8. [PubMed: 8320514]

- 42.

- Tate Maltby M, Gaszczyk D. Is it necessary to occlude the ear in bone-conduction testing at 4 kHz, in order to prevent air-borne radiation affecting the results? Int J Audiol. 2015;54(12):918-23. [PubMed: 26446950]

- 43.

- Margolis RH, Eikelboom RH, Johnson C, Ginter SM, Swanepoel de W, Moore BC. False air-bone gaps at 4 kHz in listeners with normal hearing and sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2013 Aug;52(8):526-32. [PubMed: 23713469]

- 44.

- Chung JH, Des Roches CM, Meunier J, Eavey RD. Evaluation of noise-induced hearing loss in young people using a web-based survey technique. Pediatrics. 2005 Apr;115(4):861-7. [PubMed: 15805356]

- 45.

- Rabinowitz PM. Noise-induced hearing loss. Am Fam Physician. 2000 May 01;61(9):2749-56, 2759-60. [PubMed: 10821155]

- 46.

- Halloran DR, Hardin JM, Wall TC. Validity of pure-tone hearing screening at well-child visits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 Feb;163(2):158-63. [PubMed: 19188648]

- 47.

- Ellsperman SE, Nairn EM, Stucken EZ. Review of Bone Conduction Hearing Devices. Audiol Res. 2021 May 18;11(2):207-219. [PMC free article: PMC8161441] [PubMed: 34069846]

- 48.

- Prieve BA, Schooling T, Venediktov R, Franceschini N. An Evidence-Based Systematic Review on the Diagnostic Accuracy of Hearing Screening Instruments for Preschool- and School-Age Children. Am J Audiol. 2015 Jun;24(2):250-67. [PubMed: 25760393]

- 49.

- Cywka KB, Król B, Skarżyński PH. Effectiveness of Bone Conduction Hearing Aids in Young Children with Congenital Aural Atresia and Microtia. Med Sci Monit. 2021 Sep 25;27:e933915. [PMC free article: PMC8480220] [PubMed: 34561413]

- 50.

- Polonenko MJ, Carinci L, Gordon KA, Papsin BC, Cushing SL. Hearing Benefit and Rated Satisfaction in Children with Unilateral Conductive Hearing Loss Using a Transcutaneous Magnetic-Coupled Bone-Conduction Hearing Aid. J Am Acad Audiol. 2016 Nov/Dec;27(10):790-804. [PubMed: 27885975]

- 51.

- Loughrey DG, Kelly ME, Kelley GA, Brennan S, Lawlor BA. Association of Age-Related Hearing Loss With Cognitive Function, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Feb 01;144(2):115-126. [PMC free article: PMC5824986] [PubMed: 29222544]

- 52.

- Tsakiropoulou E, Konstantinidis I, Vital I, Konstantinidou S, Kotsani A. Hearing aids: quality of life and socio-economic aspects. Hippokratia. 2007 Oct;11(4):183-6. [PMC free article: PMC2552981] [PubMed: 19582191]

- 53.

- Genther DJ, Frick KD, Chen D, Betz J, Lin FR. Association of hearing loss with hospitalization and burden of disease in older adults. JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309(22):2322-4. [PMC free article: PMC3875309] [PubMed: 23757078]

- 54.

- Lin FR, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Feb 27;172(4):369-71. [PMC free article: PMC3518403] [PubMed: 22371929]

Disclosure: Josiah Brandt declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Ryan Winters declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Authors

Josiah P. Brandt1; Ryan Winters2.Affiliations

Publication History

Last Update: January 30, 2023.

Copyright

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Publisher

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

NLM Citation

Brandt JP, Winters R. Bone Conduction Evaluation. [Updated 2023 Jan 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.