Continuing Education Activity

The inferior alveolar and lingual nerves provide sensation to the structures of the lower face, including the teeth, skin, and oral mucosa. Injuries to these nerves can be caused by surgical procedures, trauma, or tumors involving the mouth and mandible. Such injuries can cause significant discomfort during daily activities, including chewing, eating, and speaking. Healthcare providers need to understand the anatomical course of the nerves to minimize the risk of injuries. However, if an injury occurs, clinicians should be able to recognize it and accurately assess the extent of the damage. Moreover, patients with nerve damage should be managed promptly to minimize the likelihood of long-term dysfunction. This activity will cover the etiology, presentation, diagnosis, and management of inferior alveolar and lingual nerve injuries.

Objectives:

- Identify the possible causes of inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve injuries.

- Outline clinical presentations of inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve injuries.

- Review how to diagnose and classify inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve injuries.

- Summarize management of inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve injuries.

Introduction

The inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) and the lingual nerve (LN) are branches of the mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve (CN V). The IAN supplies somatic sensory innervation to the chin, lower lip, lower vestibular gingiva, molars, premolars, and alveolar bone. The LN supplies somatic sensory innervation to the lingual oral gingiva and the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.[1]

Even though it is comparatively uncommon, these nerves can be damaged during procedures performed near the mandible or the lower face; certain mandibular fractures and tumors may also injure these nerves. Patients with these injuries can experience significant discomfort during daily activities such as chewing, eating, and speaking. Healthcare providers, especially dental professionals, should be able to identify and properly manage these injuries to minimize the risk of permanent neurosensory deficits.

Etiology

It is important to understand the anatomy of the IAN and LN to avoid injury to these nerves. The mandibular branch (V3) of the trigeminal nerve exits the skull through the foramen ovale to enter the infratemporal fossa, where the IAN and LN branch off from it. The IAN enters the mandibular foramen of the ramus and runs within the body of the mandible to supply sensory innervation to the mandibular dentition, mandibular vestibular mucosa, and gingiva, as well as the skin of the chin and lower lip.[2]

The LN travels inferiorly between the mandibular ramus and the medial pterygoid muscle, then passes anteriorly near the mandibular lingual alveolar crest. Once the LN has passed the retromolar region, it travels anteriorly, along the lateral aspect of the hyoglossus muscle, and deep to the mylohyoid muscle. The LN supplies somatic sensation to the lingual gingiva and anterior two-thirds of the tongue. Of note, the chorda tympani nerve, the branch of the facial nerve that provides gustatory sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, joins the lingual nerve at the level of the inferior border of the lateral pterygoid muscle.[2] This is important to bear in mind because damage to the lingual nerve is likely to cause injury to the chorda tympani nerve, resulting in altered taste and somatic sensation on the affected side.

Local anesthetic injections are performed prior to most surgical procedures, and both the IAN and LN may be injured during attempts to place blocks around them (see figure). It is very rare, but the needle or the local anesthetic can cause direct or indirect damage to the nerve. The risk is especially increased during the IAN block because the needle travels in close proximity to both the IAN and the LN as they descend medial to the ramus of the mandible. Three theories may explain how nerve damage occurs in these situations.[3]

The injection needle may cause direct axonal trauma if it comes in contact with or penetrates the nerve. Another theory is that the needle may damage the epineural blood vessels and cause a localized hematoma, causing a compression injury to the nerve or forming reactive fibrosis or scar. The last hypothesis is that the local anesthetic itself can cause cytotoxic injuries as the chemicals are metabolized.

Another relatively common cause of IAN and LN injury is mandibular third molar extraction.[1] The inferior alveolar nerve can be damaged when the inferior alveolar canal is exposed or disrupted during surgery; surgical burs, elevators, or displaced tooth fragments may injure the nerve. The lingual nerve can be violated by surgical incisions, or it can sustain crush or traction injuries due to aggressive retraction or suturing. Mandibular orthognathic surgery also involves fracturing the mandible, occasionally resulting in IAN damage secondary to exposure and manipulation of the nerve in its canal.[4]

Likewise, mandibular fractures from trauma (frequently physical altercations or motor vehicle accidents) can lead to similar damage. Dental implant placement can cause IAN injury from either direct damage to the nerve within its canal or from thermal injury due to drilling.[3] Endodontic treatment can also lead to nerve damage from excessive instrumentation and from the chemicals that are used during the procedure.

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of IAN and LN injuries varies within the literature and depends greatly upon the etiology of the injury. Local anesthetic injection-related nerve injuries are rare, and patients tend to recover nerve function spontaneously (85-94% of the time).[5][6]

Mandibular third molar extraction is the leading surgical cause of IAN and LN injury, but rates fluctuate with operator experience and technique.[1] A 2012 study published by Guerrero et al. reported IAN injury incidences of 0.4 to 13.4% and LN injury incidences of 0 to 11% after third molar extractions.[7] The incidence of persistent IAN dysfunction ranged from 0 to 1.6%.[8]

For LN injury, the majority recovered, but 0.5-0.6% had persistent dysfunction.[9] In dental implant surgery, the incidence of temporary nerve damage ranges from 0 to 24%, and that of persistent injury ranges from 0 to 11%. There is a widely varying incidence of nerve injury resulting from mandibular orthognathic surgery; a prospective study published by Poort et al. in 2009 reviewed 20 years of procedures and reported a 20-98% incidence of IAN injury with a 0 to 82% rate of persistent dysfunction.[8] Agbaje and colleagues' 2015 systematic review of IAN injuries following bilateral sagittal split osteotomy concluded that standardized assessment and further research are required to assess the incidence accurately.[4]

With respect to non-iatrogenic injuries, the incidence of IAN damage due to traumatic mandibular fracture is 46 to 81%. The rates increase, however, after open reduction and internal fixation (77 to 91%), with permanent dysfunction occurring in 0 to 45% of cases.[8]

Histopathology

Two systems for the classification of nerve injury severity based on histological changes are commonly employed, those of Seddon and Sunderland (see table).[10][11]

Seddon's classification system is the simpler of the two, dividing injuries into neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia is the mildest form of nerve injury, characterized by transient conduction block from trauma to endoneurial capillaries that leads to edema and potentially focal demyelination without any axonal degeneration. This type of injury makes a spontaneous, full recovery. Axonotmesis occurs when there is an injury to the axons and potentially one or more of the internal connective tissue layers (endoneurium and perineurium).

Even though these injuries result in axonal degeneration, at least some recovery can be expected because the axons are able to regenerate within the intact epineurium. If the endoneurium remains intact, a complete recovery should occur, but if the endoneurium or perineurium is violated, the prognosis is worse. Neurotmesis is the most severe type of injury, characterized by complete transection of the nerve, including the axons and all of the connective tissue layers. With such an injury, there is a low likelihood of spontaneous recovery.[3]

Sunderland's classification of nerve injury further characterizes injuries based on the involvement of each layer of neural connective tissue. The first degree corresponds to neuropraxia in Seddon's classification, which involves disruption of myelin sheaths, but the axons and the rest of the internal neural architecture remain intact (see figure). Seddon's "axtonotmesis" category is divided in the Sunderland system into three distinct categories.

Second-degree injury occurs when only the axons are damaged, but all the connective tissue layers remain intact; in these cases, as in first-degree injuries, full recovery is expected. The third-degree injury involves both axonal and endoneurial injuries.

Fourth-degree injury involves damage to all structures except the epineurium: the axons, the endoneurium, and the perineurium. Fourth-degree injuries, therefore, have worse prognoses than first, second, or third-degree injuries. Sunderland's fifth-degree injury is characterized by disruption of all the nerve structures, or nerve transection, which corresponds to neurotmesis in Seddon's classification. First, second, or third-degree injuries are likely to recover spontaneously; however, fourth and fifth-degree injuries are not likely to make full sensory recoveries.[3]

History and Physical

Patients with IAN and/or LN injury typically present with chief complaints of altered sensation in the lower lip, chin, mandibular teeth, gingiva, and tongue. Specifically, with LN injury, patients are likely to also report altered taste on the ipsilateral anterior tongue due to concomitant chorda tympani damage. The ability to move the tongue and lower face should remain intact though, as the hypoglossal and facial nerves are responsible for motor innervation of these areas. That said, a change in the ability to feel in the region can interfere with numerous daily activities such as speech, eating, drinking, kissing, applying makeup, and shaving.[12]

The quality and the extent of altered sensations vary substantially among patients, who may experience paresthesias, hypo/anesthesia, and dysesthesia.[3] Paresthesia is an abnormal sensation that is not necessarily unpleasant, such as a feeling of pins and needles. Hypesthesia is a decrease in the ability to feel, and anesthesia is the complete absence of sensation; anesthesia often causes patients to believe that the affected area is paralyzed because they cannot feel any movement, but this perception is readily remedied with a mirror. Dysesthesia, on the other hand, is an abnormal sensation that is unpleasant, such as pain. Examples of dysesthesia include hyperalgesia (increased pain response to painful stimuli), hyperpathia (a painful response to repeated stimuli), anesthesia dolorosa (pain in the area of anesthesia), and allodynia (feeling pain from non-painful stimuli).

Evaluation

Evaluation of patients with IAN and LN injuries can be divided into subjective and objective evaluations. Perception of sensation varies among patients; therefore, recording neurosensory deficit quality, extent, and location at each patient visit improves longitudinal assessment of recovery or lack thereof. Additionally, patient-reported outcomes, such as the McGill pain questionnaire and visual analog scales, are also useful for outcome tracking.[8][13]

After collecting subjective data, there is a variety of objective tests that can be conducted to assess neurosensory deficit after IAN and LN injuries. These tests can be divided into two categories: mechanoreceptive and nociceptive.[8] Mechanoceptive testing evaluates non-painful stimuli, including static light touch, brush directional stroke, and two-point discrimination. Nociceptive testing focuses on pinprick tests and thermal discrimination. The precise location and extent of any positive findings should be carefully documented.

The static light touch test assesses the integrity of A-beta fibers; a cotton wisp or a Semmes-Weinstein monofilament can be used to perform the test.[8] Brush directional discrimination assesses A-alpha and A-beta fibers, which detect vibration, touch, and flutter.[3] With eyes closed, patients are asked in which direction a brush or a filament is moving. Two-point discrimination can also assess A-alpha or C fibers if sharp instruments are used. Either blunt or sharp instruments can be used to determine the minimum distance between two stimuli at which a patient can appreciate two distinct points of contact; a normal value is roughly 5 mm.[14] The pinprick test assesses A-delta and C fibers by evaluating whether a patient can feel pressure and/or sharp pain from a needle. Thermal discrimination evaluates the integrity of A-delta fibers for detecting warmth and C fibers for detecting cold.[3]

There is no universally accepted method of evaluating IAN and LN injury; however, the following is the grading system that characterizes the extent of nerve injury based on responses from the abovementioned tests. This grading system divides neurosensory deficits into three different levels: Level A (direction and two-point discrimination - A-alpha and A-beta fibers), Level B (contact detection - A-beta and A-delta fibers), and Level C (pain sensitivity - C fibers).

For a normal patient without any deficit, no altered sensation should be noted. For a patient with mild impairment, abnormal response to level A testing but intact responses to level B and C testing will be noted; a patient with this constellation of findings should make a complete recovery. With moderate nerve injury, abnormal level A and B test results will be noted with normal level C test responses; patients in this situation may recover partially or completely. With a severely impaired or severed nerve, abnormal responses will be noted on all levels, and complete recovery should not be expected.[8] Patients are typically tested at level A first, then level B, and lastly, level C.

Treatment / Management

To minimize the risk of IAN and LN injuries, clinicians must have a good understanding of neural anatomy during procedures around the mandible or on the floor of the mouth. Despite all reasonable preventive measures, however, nerve injury may still occur. This is why clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of lower facial procedures and discuss them with patients to educate them, develop treatment plans, and obtain informed consent.

Once IAN or LN injury is identified, the clinician should assess the extent of damage by performing the neurosensory testing detailed above. Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted standard for managing IAN and LN injury. Treatment strategies vary among clinicians depending on experience and comfort level. Listed below are some of the more commonly employed treatment options for IAN and LN nerve injury.

Conservative Management

- Corticosteroids: High-dose corticosteroid therapy may be initiated immediately after injury to reduce inflammation, potentially minimizing the extent of nerve damage. The evidence regarding the effectiveness of corticosteroids in preventing the development of nerve deficits is weak; however, steroids are used widely by neurosurgeons after intracranial surgery and have been shown to improve outcomes in facial nerve palsy.[9][15]

- Topical medications: For patients with pain due to nerve injury, there is some evidence that topical agents can help alleviate symptoms. Capsaicin, lidocaine, clonidine, and clonazepam can be applied to the affected areas.[9]

- Systemic pharmacologic agents: Oral medications can also be used to relieve pain from nerve injury. The use of tricyclic antidepressants and membrane stabilizers such as antiepileptics, lidocaine derivatives, and muscle relaxants has been described.[9]

Surgical Management

Surgical intervention should be considered when there is no improvement in neurosensory function for over three months, and the deficit is not acceptable to the patient.[1]

- External nerve decompression: If nerve compression is suspected as a cause of the neurosensory deficit, surrounding structures may be released or removed to help relieve pressure on the nerve. A 2012 study published by Bagheri et al. reported an 85% rate of sensory recovery after decompression.[16] Mozsary and colleagues also reported that decompression might lead to faster recovery than other nerve repair procedures.[17]

- Direct neurorrhaphy: A severed nerve may be repaired primarily via suture neurorrhaphy if there is not a significant amount of missing nerve and the ends can be brought together without tension. The reported likelihood of sensory recovery varies widely in the literature but may be as high as 90% with careful technique and optimal circumstances.[16]

- Nerve reconstruction with autogenous grafts: When the injury results in a gap between the nerve stumps >3 mm in length, nerve or vein grafts can be used to span the gap. Great auricular nerve or sural nerve grafts are most commonly harvested for this purpose, with the great auricular nerve being more convenient to use because of its location in the neck, while the sural nerve is better suited to providing longer graft segments, up to 40 cm if necessary. If there are no readily available nerves to harvest or the patient refuses to permit nerve harvest, posterior facial or external jugular veins can be used instead, although veins lack the structural architecture (endoneurium, perineurium, epineurium) that nerves have.[1] Sensory recovery rates are notably higher when nerves are used (87.3%) compared to when veins are used (60%).[1][16] While veins appear to be less effective as interposition grafts than autologous nerves are, they can be used instead of collagen sleeves to wrap and protect neurorrhaphy or even to facilitate nerve coaptation with gaps ≤3 mm.

- Removal of the offending factor: When placement of a foreign body causes nerve dysfunction, the foreign body should be removed to limit inflammation and expedite recovery. For example, when dental implant placement leads to inferior alveolar nerve damage, the implant should be removed, ideally within 36 hours of placement.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

Even though they are less common than iatrogenic injury or trauma, other conditions can alter trigeminal nerve sensation and lead to clinical presentations similar to IAN and LN injuries.[19] These include:

- Benign or malignant tumors involving the trigeminal nerve tract

- Autoimmune disorders: lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, progressive sclerosis, Sjögren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and other connective tissue diseases

- Infections: herpes zoster, herpes simplex virus, syphilis, leprosy

- Multiple sclerosis

- Vertebrobasilar disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Amyloidosis

- Sickle cell anemia

Prognosis

Ideally, an IAN or LN injury would be identified when it occurs so that repair can be accomplished immediately to maximize the chances of sensory recovery. If the injury is not identified until after the surgery, the likelihood of spontaneous recovery decreases, particularly if there is no improvement within three months. In these cases, surgical intervention should be considered.

It remains unclear, however, what the optimal timepoint is to repair an injured nerve that was identified after the completion of the procedure during which it was injured. The prognosis for sensory recovery after surgical repair of an injured IAN or LN varies among studies; however, a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that compared outcomes of surgical repair at different time points after the injury concluded that there is a trend toward better recovery with the earlier repair.[20]

Preferably, the nerve would be reconstructed within 3 to 6 months of the injury, as there seems to be a poorer prognosis for injuries older than nine months at the time of repair.[1]

Complications

The main complications of IAN and LN injury are persistent or worsening neurosensory deficits. Dysfunction in these nerves can cause significant discomfort or distress during daily activities, such as lip and tongue biting as well as drooling. More severe injuries are less likely to recover spontaneously and may require surgical intervention, which itself is not without risk.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve injuries are rare but recognized complications of numerous oral and maxillofacial procedures. Clinicians should be familiar with the risk factors that increase the chance of nerve injuries (such as complicated anatomy or prior surgery) and be able to weigh risks and benefits when deciding whether to undertake an operation on the lower face and which techniques to employ. Additionally, it is crucial to counsel patients on the risks of nerve injury and other potential operative sequelae when making shared decisions about treatment planning.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

IAN and LN injuries most commonly result from dental procedures. If an affected patient does not show signs of spontaneous sensory recovery with conservative management within three months of the injury, the patient should be referred to a specialist, such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, who can determine whether other treatment modalities, including surgical repair or decompression, would be appropriate to employ. Early recognition of IAN and LN injury and prompt referral to clinicians who can evaluate and treat these complications will increase the likelihood of functional sensory recovery. [Level 4] This may require coordination between dental providers and family practitioners, depending on who the patient first seeks out for care.

Figure

Neurology, Nerve Fascicle, Fasciculus, Epineurium, Perineurium Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure

Seddon and Sunderland classification of nerve injury PMID: 28601782, 23895713, 27983642, 31168190, 31857526, 28488619, 30615796, 25593443 Contributed by Grace Marie Nicole Biso, MD

Figure

Conventional inferior alveolar nerve block Contributed and Modified from: BodyParts3D/Anatomography, CC BY-SA 2.1 JP https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.1/jp/deed.en, via Wikimedia Commons

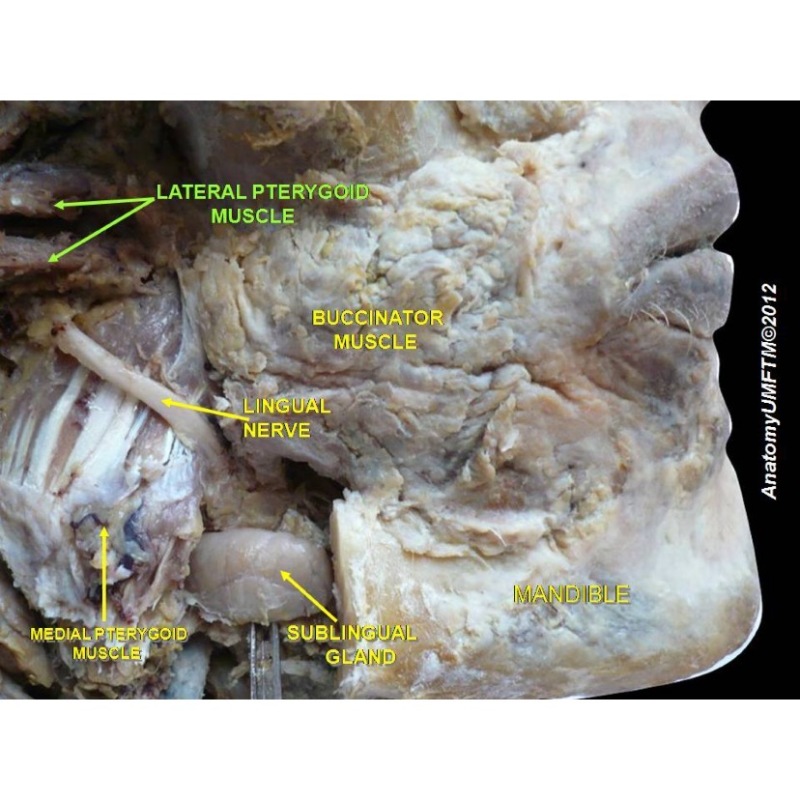

Figure

Anatomical dissection showing the lingual nerve. Contributed By Anatomist90 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25538266

Figure

Lingual nerve and its anatomical relations. Contributed By Anatomist90 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19407171

References

- 1.

- Kushnerev E, Yates JM. Evidence-based outcomes following inferior alveolar and lingual nerve injury and repair: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2015 Oct;42(10):786-802. [PubMed: 26059454]

- 2.

- Joo W, Yoshioka F, Funaki T, Mizokami K, Rhoton AL. Microsurgical anatomy of the trigeminal nerve. Clin Anat. 2014 Jan;27(1):61-88. [PubMed: 24323792]

- 3.

- Juodzbalys G, Wang HL, Sabalys G. Injury of the Inferior Alveolar Nerve during Implant Placement: a Literature Review. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2011;2(1):e1. [PMC free article: PMC3886063] [PubMed: 24421983]

- 4.

- Agbaje JO, Salem AS, Lambrichts I, Jacobs R, Politis C. Systematic review of the incidence of inferior alveolar nerve injury in bilateral sagittal split osteotomy and the assessment of neurosensory disturbances. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015 Apr;44(4):447-51. [PubMed: 25496848]

- 5.

- Pogrel MA, Thamby S. Permanent nerve involvement resulting from inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Jul;131(7):901-7. [PubMed: 10916328]

- 6.

- Aquilanti L, Mascitti M, Togni L, Contaldo M, Rappelli G, Santarelli A. A Systematic Review on Nerve-Related Adverse Effects following Mandibular Nerve Block Anesthesia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 31;19(3) [PMC free article: PMC8835670] [PubMed: 35162650]

- 7.

- Guerrero ME, Nackaerts O, Beinsberger J, Horner K, Schoenaers J, Jacobs R., SEDENTEXCT Project Consortium. Inferior alveolar nerve sensory disturbance after impacted mandibular third molar evaluation using cone beam computed tomography and panoramic radiography: a pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Oct;70(10):2264-70. [PubMed: 22705219]

- 8.

- Poort LJ, van Neck JW, van der Wal KG. Sensory testing of inferior alveolar nerve injuries: a review of methods used in prospective studies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009 Feb;67(2):292-300. [PubMed: 19138602]

- 9.

- Graff-Radford SB, Evans RW. Lingual nerve injury. Headache. 2003 Oct;43(9):975-83. [PubMed: 14511274]

- 10.

- Seddon HJ. A Classification of Nerve Injuries. Br Med J. 1942 Aug 29;2(4260):237-9. [PMC free article: PMC2164137] [PubMed: 20784403]

- 11.

- Sunderland S. The anatomy and physiology of nerve injury. Muscle Nerve. 1990 Sep;13(9):771-84. [PubMed: 2233864]

- 12.

- Ziccardi VB, Assael LA. Mechanisms of trigeminal nerve injuries. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2001 Sep;9(2):1-11. [PubMed: 11665372]

- 13.

- Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975 Sep;1(3):277-299. [PubMed: 1235985]

- 14.

- Kawamura P, Wessberg GA. Normal trigeminal neurosensory responses. Hawaii Dent J. 1985 Apr;16(4):8-11. [PubMed: 3864769]

- 15.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, Davenport RJ, Vale LD, Clarkson JE, Hammersley V, Hayavi S, McAteer A, Stewart K, Daly F. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell's palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 18;357(16):1598-607. [PubMed: 17942873]

- 16.

- Bagheri SC, Meyer RA, Cho SH, Thoppay J, Khan HA, Steed MB. Microsurgical repair of the inferior alveolar nerve: success rate and factors that adversely affect outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Aug;70(8):1978-90. [PubMed: 22177818]

- 17.

- Mozsary PG, Syers CS. Microsurgical correction of the injured inferior alveolar nerve. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985 May;43(5):353-8. [PubMed: 3857299]

- 18.

- Pogrel MA, McDonald AR, Kaban LB. Gore-Tex tubing as a conduit for repair of lingual and inferior alveolar nerve continuity defects: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998 Mar;56(3):319-21; discussion 321-2. [PubMed: 9496843]

- 19.

- Peñarrocha M, Cervelló MA, Martí E, Bagán JV. Trigeminal neuropathy. Oral Dis. 2007 Mar;13(2):141-50. [PubMed: 17305614]

- 20.

- Suhaym O, Miloro M. Does early repair of trigeminal nerve injuries influence neurosensory recovery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Jun;50(6):820-829. [PubMed: 33168370]

Disclosure: Gloria Kwon declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Marc Hohman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Authors

Gloria Kwon1; Marc H. Hohman2.Affiliations

Publication History

Last Update: March 1, 2023.

Copyright

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Publisher

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

NLM Citation

Kwon G, Hohman MH. Inferior Alveolar Nerve and Lingual Nerve Injury. [Updated 2023 Mar 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.