Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Reuter-Sandquist M; Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN); Ernstmeyer K, Christman E, editors. Nursing Assistant [Internet]. Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College; 2022.

4.1. INTRODUCTION TO ADHERE TO PRINCIPLES OF INFECTION CONTROL

Learning Objectives

• Discuss principles of medical asepsis for client and personal safety

• Describe methods to prevent blood-borne pathogen transmission

• Apply principles of standard and transmission-based precautions and infection prevention

Infection control, also called infection prevention, prevents or stops the spread of infections in health care settings.[1] Facilities hire licensed health professionals who are in charge of infection prevention, but everyone is responsible for reducing the spread of infection. This chapter will discuss the manner in which infections spread, common signs and symptoms of infection, and infection control basics, including methods to protect you and those you care for from infection.

4.2. CHAIN OF INFECTION

The chain of infection, also referred to as the chain of transmission, describes how an infection spreads based on these six links of transmission:

- Infectious Agent

- Reservoirs

- Portal of Exit

- Modes of Transmission

- Portal of Entry

- Susceptible Host

See Figure 4.1[1] for an illustration of the chain of infection. If any “link” in the chain of infection is removed or neutralized, transmission of infection will not occur. Health care workers must understand how an infectious agent spreads via the chain of transmission so they can break the chain and prevent the transmission of infectious disease. Routine hygienic practices, standard precautions, and transmission-based precautions are used to break the chain of transmission.

Figure 4.1

Chain of Infection

The links in the chain of infection include Infectious Agent, Reservoir, Portal of Exit, Mode of Transmission, Portal of Entry, and Susceptible Host[2]:

- Infectious Agent: Microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, that can cause infectious disease.

- Reservoir: The host in which infectious agents live, grow, and multiply. Humans, animals, and the environment can be reservoirs. Examples of reservoirs are a person with a common cold, a dog with rabies, or standing water with bacteria. Sometimes a person may carry an infectious agent but is not symptomatic or ill. This is referred to as being colonized, and the person is referred to as a carrier. For example, many health care workers carry methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria in their noses but are not symptomatic.

- Portal of Exit: The route by which an infectious agent escapes or leaves the reservoir. In humans, the portal of exit is typically a mucous membrane or other opening in the skin. For example, pathogens that cause respiratory diseases usually escape through a person’s nose or mouth.

- Mode of Transmission: The way in which an infectious agent travels to other people and places because they cannot travel on their own. Modes of transmission include contact, droplet, or airborne transmission. For example, touching sheets with drainage from one person’s infected wound and then touching another person without washing one’s hands is an example of contact transmission of an infectious agent. Examples of droplet or airborne transmission are coughing and sneezing, depending on the size of the microorganism.

- Portal of Entry: The route by which an infectious agent enters a new host (i.e., the reverse of the portal of exit). For example, mucous membranes, skin breakdown, and artificial openings in the skin created for the insertion of medical equipment (such as intravenous lines) are at high risk for infection because they provide an open path for microorganisms to enter the body. Tubes inserted into mucous membranes, such as a urinary catheter, also facilitate the entrance of microorganisms into the body. A person’s immune system fights against infectious organisms that have entered the body through the use of nonspecific and specific defenses. Read more about defenses against microorganisms in the “Defenses Against Transmission of Infection” section of this chapter.

- Susceptible Host: A person at elevated risk for developing an infection when exposed to an infectious agent due to changes in their immune system defenses. For example, infants (up to 2 years old) and older adults (aged 65 or older) are at higher risk for developing infections due to underdeveloped or weakened immune systems. Additionally, anyone with chronic medical conditions (such as diabetes) are also at higher risk of developing an infection. In health care settings, almost every patient is considered a “susceptible host” because of preexisting illnesses, medical treatments, medical devices, or medications that increase their vulnerability to developing an infection when exposed to infectious agents in the health care environment. As caregivers, it is the NA’s responsibility to protect susceptible patients by breaking the chain of infection.

After a susceptible host becomes infected, they become a reservoir that can then transmit the infectious agent to another person. If an individual’s immune system successfully fights off the infectious agent, they may not develop an infection, but instead the person may become an asymptomatic “carrier” who can spread the infectious agent to another susceptible host. For example, individuals exposed to COVID-19 may not develop an active respiratory infection but can spread the virus to other susceptible hosts via sneezing.

Learn more about the chain of infection by clicking on the following activities.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Note: To enlarge the print, you can expand the activity by clicking the arrows in the right upper corner of the text box. Please drag and drop the descriptors and actions into the appropriate boxes to demonstrate the various steps in the chain of infection.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Healthcare-Acquired Infections

An infection that develops in an individual after being admitted to a health care facility or undergoing a medical procedure is a healthcare-associated infection (HAI), formerly referred to as a nosocomial infection. About 1 in 31 hospital patients develops at least one healthcare-associated infection every day. HAIs increase the cost of care and delay recovery. They are associated with permanent disability, loss of wages, and even death. An example of an HAI is a skin infection that develops in a patient’s incision after they had surgery due to improper hand hygiene of health care workers.[3],[4] It is important to understand the dangers of Healthcare-Acquired Infections and actions that can be taken to prevent them.

Read more details about healthcare-acquired infections in the “Infection” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Healthcare-Associated Infections by Michelle Hughes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

- 1.

- “Chain-of-Transmission” by unknown author is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Access for free at https:

//ecampusontario .pressbooks.pub/introductiontoipcp /chapter/40/ ↵. - 2.

- Department of Health. (n.d.). Chain of infection in infection prevention and control (IPAC). The Government of Nunavut. https://www

.gov.nu.ca /health/information /infection-prevention-and-control ↵. - 3.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 4.

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www

.hhs.gov/oidp /topics/health-care-associated-infections/index.html ↵.

4.3. DEFENSES AGAINST TRANSMISSION OF INFECTION

The body tries to protect itself from infectious agents by using specific and nonspecific defenses. Specific defenses are immune system processes that include white blood cells attacking particular pathogens. Nonspecific defenses are generic barriers that prevent pathogens from entering the body, including physical, mechanical, or chemical barriers.

Physical Defenses

Physical defenses are the body’s most basic form of defenses against infection. Physical defenses include barriers such as skin and mucous membranes, as well as mechanical defenses, that physically remove microbes from areas of the body.[1]

SKIN

One of the body’s most important physical barriers is the skin barrier that is composed of three layers of closely packed cells. See Figure 4.2[2] for an illustration of layers of the skin. The topmost layer of skin, called the epidermis, consists of cells that are packed with keratin. Keratin makes the skin’s surface mechanically tough and resists degradation by bacteria. When the skin barrier becomes broken, such as becoming cracked from dryness, microorganisms can enter and cause infection.[3]

Figure 4.2

Skin Layers

MUCOUS MEMBRANES

Mucous membranes lining the nose, mouth, lungs, and urinary and digestive tracts provide another nonspecific barrier against pathogens. Mucous is a moist, sticky substance that covers and protects the layers beneath it and also traps debris, including microbes. Mucus secretions also contain antimicrobial agents.[4]

In many regions of the body, mechanical actions flush mucus (along with trapped microbes) out of the body or away from potential sites of infection. For example, in the respiratory system, inhalation can bring microbes, dust, mold spores, and other small airborne debris into the body. This debris becomes trapped in the mucus lining the respiratory tract. The cells lining the upper parts of the respiratory tract have hair-like appendages known as cilia. Movement of the cilia propels debris-laden mucus out and away from the lungs. The expelled mucus is then swallowed (and destroyed in the stomach) or coughed out. However, smoking limits the efficiency of this system, making smokers more susceptible to developing respiratory infections. Additionally, as people age, their chest muscles weaken, and coughing becomes less productive, which also increases the risk of developing a respiratory infection.

Mechanical Defenses

In addition to physical barriers, the body has several mechanical defenses that physically remove pathogens from the body and prevent infection. For example, the flushing action of urine carries microbes away from the body and is responsible for maintaining a sterile environment of the urinary tract.

The eyes have additional physical barriers and mechanical mechanisms for preventing infections. Eyelashes and eyelids are physical barriers that prevent dust and airborne microorganisms from reaching the surface of the eye. Any microbes or debris that make it past these physical barriers are flushed out by the mechanical action of blinking. Blinking bathes the eye in tears and washes debris away.[5] See Figure 4.3[6] for an example of eyelashes as a mechanical defense.

Figure 4.3

Eyelashes Are a Mechanical Defense Against Pathogens

Chemical Defenses

In addition to physical and mechanical defenses, our immune system uses several chemical defenses that inhibit microbial invaders. The term chemical mediators refers to a wide array of substances found in various fluids and tissues throughout the body. For example, sebaceous glands in the dermis secrete an oil called sebum that is released onto the skin surface through hair follicles. Sebum provides an additional layer of defense by helping seal off the pore of the hair follicle and preventing bacteria on the skin’s surface from invading sweat glands and surrounding tissue. However, environmental factors can affect these chemical defenses of the skin. For example, low humidity in the winter dries the skin and makes it more susceptible to pathogens that are normally inhibited by the skin’s low pH. Application of skin moisturizer restores moisture and essential oils to the skin and helps prevent dry skin from becoming infected.[7]

Other types of chemical defenses are pH levels, chemical mediators, and enzymes. For example, in the urinary tract, the slight acidity of urine inhibits the growth of potential pathogens in the urinary tract. The respiratory tract has various chemical mediators in the nasal passages, trachea, and lungs that have antibacterial properties. Enzymes in the digestive tract eliminate most microorganisms that survive the acidic environment of the stomach. However, feces, the end product of the digestive system, can still contain some microorganisms. For this reason, hand hygiene is vital after using the restroom or assisting a client with perineal care to prevent the spread of infection.[8]

References

- 1.

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵. - 2.

- “OSC

_Microbio_17_02_Skin.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax .org /books/microbiology/pages /17-1-physical-defenses ↵. - 3.

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵. - 4.

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵. - 5.

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵. - 6.

- 7.

- This work is a derivative of Microbiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction ↵. - 8.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

4.4. PRECAUTIONS USED TO PREVENT THE SPREAD OF INFECTION

Health care agencies use several methods to prevent the spread of infection: standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used by health care workers during client care when contact or potential contact with blood or body fluids may occur. Standard precautions should also be used when assisting a client with activities of daily living (ADLs) and using water, soap, or lotion. Standard precautions are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These precautions reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect patients from potential transmission of infectious organisms.[1]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions include the following[2]:

- Using proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times

- Using personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever exposure to infectious agents may occur

- Implementing respiratory hygiene for staff, patients, and visitors

- Proper cleaning and sanitizing of the environment, equipment, and devices

- Handling laundry safely

- Using transmission-based precautions when indicated

Hand Hygiene

The easiest and most effective way to break the chain of infection is by using proper hand hygiene at appropriate times during patient care. Knowing when to wash your hands, how to properly wash your hands, and when to use soap and water or hand sanitizer are vital for reducing the spread of infection and keeping yourself healthy. Hand hygiene is the process of removing, killing, or destroying microorganisms or visible contaminants from the hands. There are two hand-hygiene techniques: handwashing with soap and water and the use of alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR), also referred to as hand hygiene gel or hand sanitizer.[3]

Health care providers’ hands are the most common mode of transmission of microorganisms. As a nursing assistant, your hands will touch many people and objects when providing care. When you touch a client, their personal items, medical equipment, or their surrounding environment, you can indirectly transmit microorganisms to the client, another client, yourself, equipment, or a new environment. Microorganisms can easily be transferred from your hands to others or objects in the health care setting if proper hand hygiene practices are not followed. Consistent and effective hand hygiene is vital for breaking the chain of transmission.[4]

It is essential for all health care workers to use proper hand hygiene during specific moments of patient care[5]:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task, such as emptying urine from a Foley catheter bag

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without gloves)

- Immediately after glove removal

See Figure 4.4[6] for an illustration of the five moments of hand hygiene.

Figure 4.4

Moments of Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene also includes health care workers keeping their nails short with tips less than 0.5 inches and no nail polish. Nails should be natural, and artificial nails or tips should not be worn. Artificial nails and chipped nail polish have been associated with a higher level of pathogens carried on the hands of health care workers despite using proper hand hygiene.[7]

Review the Moments of Hand Hygiene by clicking on the interactive activity below.

This work is a derivative of Your 4 Moments for Hand Hygiene by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Proper hand hygiene includes handwashing with soap and water or the use of alcohol-based hand rub. Both procedures are described in the following sections.

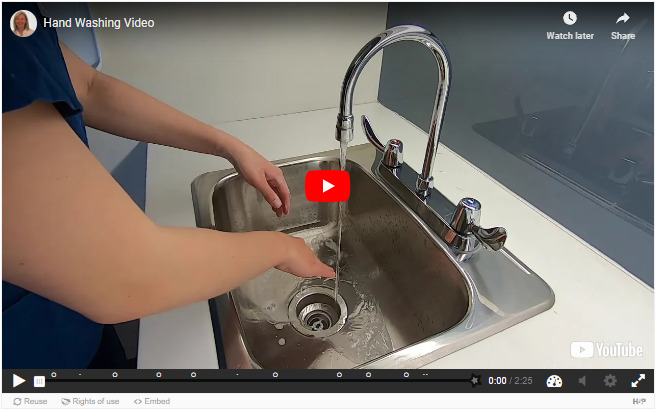

HANDWASHING WITH SOAP AND WATER

Handwashing involves the use of soap and water to physically remove microorganisms from one’s hands. Certain health care situations require handwashing with soap and water instead of using alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR). For example, hands must be washed with soap and water if they are visibly soiled, have been exposed to blood or body fluids, or have been exposed to norovirus, C. difficile, or Bacillus anthracis. The mechanical action of lathering and scrubbing with soap for a minimum of 20 seconds is vital for removing these types of microorganisms.[8]

Soap is required during handwashing to dissolve fatty materials and facilitate their subsequent flushing and rinsing with water. Soap must be rubbed on all surfaces of both hands followed by thorough rinsing and drying. Water alone is not suitable for cleaning soiled hands. The entire procedure should last 40 to 60 seconds, and soap approved by the health agency should be used.[9]

When washing with soap and water, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following steps[10]:

- Wet hands with warm or cold running water and apply facility-approved soap.

- Lather hands by rubbing them together with the soap. Use the same technique as the hand rub process to clean the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- Scrub thoroughly for at least 20 seconds.

- Rinse hands well under clean, running water.

- Dry the hands, using a clean towel or disposable toweling, from fingers to wrists.

- Use a clean paper towel to shut off the faucet.

See Figure 4.5[11] for an illustration of handwashing with soap and water.

Figure 4.5

How to Handwash with Soap and Water

See the “Skills Checklist: Hand Hygiene With Soap and Water” section later in this chapter for a checklist of steps and an associated demonstration video of this procedure. Common safety considerations and errors when washing hands are described in the following box.

Safety Considerations[12]

- Always wash hands with soap and water if hands are visibly soiled.

- When working with clients where C. difficile, norovirus, or Bacillus anthracis is suspected or confirmed, soap and water must be used. It is more effective in physically removing the C. difficile spores compared to ABHR, which is not as effective at penetrating the spores.

- Friction and rubbing are required to remove transient bacteria, oil, and debris from hands.

- Always use soap and water if hands are exposed to blood, body fluids, or other body substances.

- Multistep rubbing techniques using soap and water are required to promote coverage of all surfaces on hands.

Common Errors When Washing Hands With Soap and Water[13]

- Not using enough soap to cover all surfaces of the hands and wrists.

- Not using friction when washing hands.

- Not washing hands long enough. The mechanical action of lathering and scrubbing should be a minimum of 20 seconds, and the entire procedure should last 40 to 60 seconds.

- Missing areas such as the fingernails, wrists, backs of hands, and thumbs.

- Not removing all soap from hands and wrists.

- Shaking water off hands.

- Not thoroughly drying the hands.

- Drying hands from wrists to fingers or in both directions.

Practice your knowledge by clicking on this interactive learning activity.

This work is a derivative of the YouTube Hand Washing Video by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

ALCOHOL-BASED HAND RUB

When performing hand hygiene using the alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) technique, a liquid, gel, or foam alcohol-based solution is used. ABHR is the preferred method for hand hygiene when soap and water handwashing is not required. It reduces the number of transient microorganisms on hands and is more effective for preventing healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) caused by Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE). Hand hygiene with ABHR should be performed in front of the client prior to the beginning of care and at the end of the interaction. ABHR provided by the agency should be used with a 70–90% alcohol concentration.[14]

The benefits of ABHR include the following[15]:

- It kills the majority of microorganisms (including viruses) from hands.

- It requires less time than soap and water handwashing.

- It provides better skin tolerability and reduces skin irritation because it contains emollients.

- It is easy to use and available at the point of care (i.e., where three elements of the client, the health care provider, and care involving the client occur together).

Read safety considerations and common errors when using ABHR in the following box. See the “Skills Checklist: Hand Hygiene With Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer” section later in this chapter for a checklist of steps and an associated demonstration video of this procedure.

Safety Considerations[16]

- Do not use ABHR in combination with soap and water because it may increase skin irritation.

- Use ABHR that contains emollients (oils) to help reduce skin irritation and overdrying.

- Allow hands to dry completely before initiating tasks (e.g., touching the client or the environment or applying clean gloves).

- Use ABHR for all moments of hand hygiene if soap and water are not required.

- DO NOT use ABHR if hands are visibly soiled, have been exposed to blood or body fluids, or the client is suspected to have C. difficile, norovirus, or Bacillus anthracis.

- Only use ABHR supplied by the facility.

Common Errors When Performing an ABHR[17]

- Not letting hands air dry (for example, rubbing one’s hands on pants to dry it off).

- Shaking hands to dry.

- Applying too much alcohol-based solution.

- Not applying enough alcohol-based solution.

- Not rubbing hands long enough (a minimum of 20 seconds) and until hands are dry.

- Missing areas such as the fingernails, wrists, backs of the hands, and thumbs.

Practice your knowledge by clicking on this interactive learning activity.

This work is a derivative of Performing an Alcohol-Based Hand Rub by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Respiratory Hygiene and Other Hygienic Practices

Respiratory hygiene should be used by any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, or increased production of respiratory secretions to prevent the spread of infection. Respiratory hygiene refers to coughing or sneezing into the inside of one’s elbow or covering one’s mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and promptly disposing of used tissues. Hand hygiene should be immediately performed after contact with one’s respiratory secretions. A coughing person should also wear a surgical mask to contain secretions.[18]

Additional hygiene measures are also used to prevent the spread of infection. For example, regularly changing bed linens, towels, and hospital gowns eliminates potential reservoirs of bacteria. Gripper socks should be removed before patients get into bed to prevent pathogens from the floor from being transferred to the patient’s bed linens.

Mobile devices should be cleaned regularly. Research has shown that cell phones and mobile devices carry many pathogens and are dirtier than a toilet seat or the bottom of a shoe. Patients, staff, and visitors routinely bring mobile devices into health care facilities that can cause the spread of infection. Mobile devices should be frequently wiped with disinfectant.

Disinfection and Sterilization

Disinfection and sterilization are procedures used to remove harmful pathogens from equipment and the environment to decrease the risk of spreading infection. Disinfection is the removal of microorganisms, but it does not destroy all spores and viruses. Sterilization destroys all pathogens on equipment or in the environment, including spores and viruses, and includes methods such as steam, boiling water, dry heat, radiation, and chemicals. Because of the harshness of sterilization methods, skin can only be disinfected and not sterilized.[19]

Asepsis refers to the absence of infectious material or infection. Surgical asepsis is the absence of all microorganisms during any type of invasive procedure, such as during surgery or heart catheterizations. Sterilization is performed on equipment used during invasive procedures. As a nursing assistant, you may assist a registered nurse during a procedure requiring sterile technique; however, performing sterile procedures independently is not in the scope of practice for nursing assistants.

In long-term care and other health care settings other than surgery, medical asepsis is used. Medical asepsis refers to techniques used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another but do not eliminate all microorganisms. Nursing assistants implement medical asepsis in the following ways:

- Performing hand hygiene at the appropriate moments of patient care. (See previous Figure 4.4.)

- Using a barrier when placing clean linens, wash basins, and other items on a shared surface such as the countertop in a resident’s room.

- Pulling the privacy curtain when one resident has a droplet-transmitted infection to protect transmission to the other resident in a shared room.

- Cleaning equipment (such as blood pressure cuffs) between use on residents.

- Starting with “cleaner” areas of the body when assisting with care and then moving to areas with higher levels of microorganisms. For example, when bathing a client, the face is washed first, followed by the upper body and then finishing with perineal care. (Perineal care involves washing the genital and rectal areas of the body.)

Laundry

When handling dirty linens, textiles, and patients’ clothing, follow agency policy regarding transport to prevent the potential spread of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that contaminated textiles and fabrics should be handled with minimal agitation to avoid contamination of air, surfaces, and other individuals. They should be bagged at the point of use, and leak-resistant bags should be used for textiles and fabrics contaminated with blood or body substances.[20]

Transmission-Based Precautions

When providing care for individuals with known or suspected infections, additional precautions are used in addition to the previously discussed standard precautions. Certain types of pathogens and communicable diseases are easily transmitted to others and require additional precautions to interrupt the spread of infectious agents to health care workers and other clients. For example, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), C. difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB) require transmission-based precautions.

Transmission-based precautions (commonly referred to as isolation precautions) use specific types of personal protective equipment (PPE) and practices based on the pathogen’s mode of transmission. It is vital for nursing assistants to understand what PPE should be used in specific client care situations, which is determined by the pathogen’s mode of transmission and their possible risk of exposure.[21] Transmission-based precautions include three categories: contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. Read more about each type of transmission-based precaution in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1

| Transmission-Based Precaution | PPE Required | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Gloves and gown, possibly face shield | Used for clients with known or suspected infections such as C-difficile (C-diff), methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin resistant enterococcus (VRE), or norovirus transmitted by touch (e.g., drainage from wounds or fecal incontinence). Contact precautions should be used when there is expected contact with the source of the pathogen or any surfaces within the resident’s room. For example, MRSA in a client’s wound transmits with direct contact with the wound, so wearing gloves and a gown when entering the room with a meal tray is typically sufficient. However, MRSA in a client’s urine could be accidentally splashed onto one’s mucous membrane when emptying the bag of an indwelling urinary catheter, so a face shield is also necessary for this task, in addition to wearing gloves and a gown. |

| Droplet | Gloves and a mask | Used for clients with a diagnosed or suspected pathogen that is spread in small droplets from sneezing or other oral and nasal secretions, such as influenza or pertussis. Droplets can travel six feet, so using barriers such as privacy curtains and closing doors can also prevent the spread of infection to others. |

| Airborne | Gloves and respirator | Used for clients with diagnosed or suspected pathogens spread by very small airborne particles from nasal and oral secretions that can float long distances through the air, such as measles and tuberculosis. Respirators are specially designed masks that fit closely on the face and filter out small particles, including the virus that causes COVID. Clients must be placed in a room with specialized air handling equipment found in doctors’ offices and hospitals. Residents in long-term care settings suspected of having an airborne illness should be transferred immediately to prevent the spread of infection to other residents. |

Signage for Transmission-Based Precautions

When a resident has an infectious illness requiring transmission-based precautions, a sign is placed on their door and a cart of PPE supplies is placed nearby. Signs vary by facility but look similar to the image in Figure 4.6.[25] Due to HIPAA regulations, the type of the pathogen and the source cannot be displayed publicly, so the sign instructs anyone wishing to enter the room to ask the nurse first. Additional information regarding the type and source of the infection can be found in the client’s nursing care plan. After you become aware of the pathogen, the source, and the required PPE, you can safely enter the room. If you are unsure about any aspect of PPE required or your risk of exposure, talk to the nurse before entering the room or providing care.

Figure 4.6

Example of Isolation Precautions Sign

View the following YouTube video from the University of Iowa about isolation precautions in a health care setting: Standard and Isolation Precautions.

References

- 1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 3.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 4.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 29). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www

.cdc.gov/handhygiene/ ↵. - 6.

- “5Moments_Image.gif” by World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www

.who.int/infection-prevention /campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵. - 7.

- Blackburn, L., Acree, K., Bartley, J., DiGiannantoni, E., Renner, E., & Sinnott, L. T. (2020). Microbial growth on the nails of direct patient care nurses wearing nail polish. Oncology Nursing Forum , 47(2), 155-164. ↵ 10.1188/20.onf.155-164 . [PubMed: 32078608] [CrossRef]

- 8.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 9.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 10.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 11.

- “How

_To_HandWash_Poster.pdf” by World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www .who.int/infection-prevention /campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵. - 12.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 13.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 14.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 16.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 17.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 18.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /standard-precautions.html ↵. - 19.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 20.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 29). Infection control. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /index.html ↵. - 21.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 22.

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www

.hhs.gov/oidp /topics/health-care-associated-infections/index.html ↵. - 23.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 24.

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /guidelines /isolation/index.html ↵. [PMC free article: PMC7119119] [PubMed: 18068815] - 25.

- “contact-precautions-sign-P.pdf” by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /basics /transmission-based-precautions .html#anchor_1564058318 ↵.

4.5. PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE)

In health care settings, personal protective equipment (PPE) refers to specialized clothing or equipment used to prevent the spread of infection, including gloves, gowns, facial protection (masks and eye protection), and respirators. PPE is a barrier that protects the health care worker from exposure to infectious agents and also prevents the transmission of microorganisms to other individuals including staff, patients, and visitors.

Gloves

Gloves are disposable, one-time-use coverings that protect the hands of health care providers. See Figure 4.7[1] for an image of nonsterile medical gloves in various sizes in a health care setting. Gloves are used to protect the hands of a health care worker from coming into contact with a client’s potentially infected body fluids and to protect patients from coming into contact with potential contaminants on health care workers’ hands during certain procedures and treatments. Gloves should also be worn by a health care worker when there is a risk of transmitting their own body fluids from nonintact skin on their hands to other individuals. However, gloves should not be worn for routine activities such as taking vital signs or transferring a client in a wheelchair unless indicated due to transmission-based precautions.

Figure 4.7

Gloves

Gloves are typically made from latex, nitrile, and vinyl. Many people are allergic to latex, so be sure to check for latex allergies for the patient and other members of the health care team. Most gloves are not hand-specific and can be worn on either the left or right hand. Gloves come in a variety of sizes such as small, medium, large, and extra large and should have a snug fit, not too tight or too loose, to provide better protection to the health care provider.[2]

Gloves should always be used in combination with proper hand hygiene that is performed prior to applying gloves and repeated again after gloves are removed. Gloves are task-specific and should not be worn for more than one task or procedure on the same client because some tasks may have a greater concentration of microorganisms than others. For example, gloves are worn to assist a client with incontinent care, but gloves should be removed, hand hygiene performed, and new gloves applied before assisting with oral care. Gloves should never be reused or washed to be reused. Reusing gloves has been linked with the transmission of infectious microorganisms.

Gloves should never replace hand hygiene for several reasons[3]:

- Gloves may have imperfections such as holes or cracks that are not visible.

- Hands may have become contaminated while removing the gloves.

- Gloves may have become damaged while wearing.

Fingernails should be short prior to applying gloves so they do not puncture the gloves. Put on (don) gloves after hands are completely dry after performing hand hygiene. There is no specific method for putting on gloves, but care should be taken when donning gloves to avoid tearing. Gloves should be applied so they completely cover the wrists. Gloves must be removed carefully, followed by proper hand hygiene, to prevent the spread of infection.[4]

REMOVING GLOVES

See Figure 4.8[5] for an illustration of properly removing gloves. Hand hygiene should be performed following glove removal to ensure the hands will not carry potentially infectious agents that might have penetrated through unrecognized tears or contaminated the hands during glove removal.

Figure 4.8

How to Remove Gloves to Prevent Contamination

Properly removing gloves includes the following steps[6]:

- Grasp the outside of one glove near the wrist. Do not touch your skin.

- Peel the glove away from your body, pulling it inside out.

- Hold the removed glove in your gloved hand.

- Put your fingers inside the glove at the top of your wrist and peel off the second glove.

- Turn the second glove inside out while pulling it away from your body, leaving the first glove inside the second.

- Dispose of the gloves safely. Do not reuse.

- Perform hand hygiene immediately after removing the gloves.

Review infection prevention and control practices related to glove usage in the following interactive activity.

This work is a derivative of Infection Prevention and Control Practices by Michelle Hughes and Kendra Allen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Isolation Gowns

Isolation gowns are protective garments worn to protect clothing from the splashing or spraying of body fluids and reduce the transmission of microorganisms. Isolation gowns can be disposable or reusable. The gowns should have long sleeves with a snug fit at the wrist, cover both the front and the back of the body from the neck to the thighs, and overlap at the back.

Gloves should fit over the cuffs of the gown. Gowns should fasten at the neck and waist using ties, snaps, or Velcro.[7]

Disposable gowns are made from materials that make them resistant to fluids. Reusable gowns are made of tightly woven cotton or polyester and are chemically finished to improve their ability to be fluid resistant; they are laundered after each use. Gowns are considered task-specific and should be changed if they become heavily soiled or damaged. Isolation gowns should be put on immediately prior to providing client care and should be removed immediately after care is completed before leaving the room. After use, gowns should be discarded into an appropriate receptacle for disposal or to be laundered if the gown is reusable. See Figure 4.9[8] for an image of an isolation gown.

Figure 4.9

Isolation Gown

Special care should be taken when removing the gown to prevent contamination of clothing and skin. The front of the gown is always considered to be contaminated. Ties at the front are considered contaminated, but ties at the side and the back are considered uncontaminated.[9]

See the “Donning/Doffing PPE” checklists later in this chapter for steps for proper removal of gowns. Review information related to using isolation gowns in the following interactive activity.

This work is a derivative of Important Considerations When Wearing Gowns by Audrey Kenmir and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Eye Protection

Eye protection in health care settings includes face shields, visors attached to masks, and goggles that are used to protect the eyes from blood or body fluids. Eye protection should be worn by health care workers during patient care when there may be splashing or spraying of body fluids or within six feet of a coughing client. For example, eye protection is worn when emptying a urinary catheter or assisting a nurse in irrigating a wound or suctioning a client’s airway.

Eye protection can be disposable, like face shields, or reusable, like eye goggles. If eye protection is reusable, it should be cleaned before reuse. Face shields and visors attached to masks offer better visibility than goggles. Eye protection should fit comfortably and securely while allowing for visual acuity. Eyeglasses can be worn under face shields or goggles.[10] See Figure 4.10[11] for an image of eye goggles with and without a face shield.

Figure 4.10

Eye Goggles With and Without a Face Shield

Review information related to the use of eye protection in the following learning activity.

This work is a derivative of Important Considerations When Wearing Eye Protection by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Masks

Masks are protective coverings worn by health care providers to protect the mucous membranes of their nose and mouth. In long-term care settings, masks are typically secured by elastic loops around the ears. The top edge of the mask has a bendable strip to secure the seal of the mask over the bridge of the nose. Some situations require masks to be combined with a face shield or a visor that covers the eyes. See Figure 4.11[12] for an image of masks used with eyeglasses and an eyeshield.

Figure 4.11.

Medical Mask With and Without an Eye Shield

Medical masks should be worn when providing care that may cause splashing or spraying of blood or body fluids or within six feet of a client who is coughing or has been placed in droplet precautions. Medical masks should also be worn by health care providers who are coughing to prevent transmission of exhaled respiratory droplets to clients.

Medical masks can differ in their filtration effectiveness and the way in which they fit. Single-use disposable medical masks are effective when providing care to most clients and should be changed when damp or soiled. When medical masks become moist, they may not provide an effective barrier to microorganisms. A medical mask, when properly worn, should fit snugly over the nose, mouth, and under the chin so that microorganisms and body fluids cannot enter or exit through the sides of the mask. If the health care worker wears glasses, the glasses should be placed over the top edge of the mask. This will help prevent the glasses from becoming foggy as the person wearing the mask exhales.

REMOVING FACEMASKS

Like the isolation gown, the front of the mask is considered contaminated. The mask should be removed by taking the ear loop off and placing it in the appropriate disposal area. It is important to properly remove masks to avoid contamination. See Figure 4.12[13] for an illustration of how to remove a facemask according to the CDC. See the “Donning/Doffing PPE With a Mask and Face Shield or Goggles” checklist for more details.

Figure 4.12

Removing Facemasks

Review information on wearing medical masks in the following interactive learning activities.

This work is a derivative of Important Considerations When Wearing Medical Masks by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

This work is a derivative of Important Considerations When Wearing Medical Masks by Michelle Hughes and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Respirators and PAPRs

Residents requiring airborne transmission precautions are transferred to a hospital immediately upon suspicion or confirmation of an airborne illness as respiratory protection used with airborne transmission precautions requires special equipment. Respirator masks with N95 or higher filtration are worn by health care professionals to prevent inhalation of infectious small airborne particles. It is important to apply, wear, and remove respirators appropriately to avoid contamination. A user-seal check should be performed by the wearer each time a respirator is donned to minimize air leakage around the facepiece. See Figure 4.13[14] for CDC recommendations when wearing disposable respirators.

Figure 4.13

How to Put On and Take Off a Respirator Mask

A newer piece of equipment used for respiratory protection is the powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). A PAPR is an air-purifying respirator that uses a blower to force air through filter cartridges or canisters into the breathing zone of the wearer. This process creates an air flow inside either a tight-fitting facepiece or loose-fitting hood or helmet, providing a higher level of protection against aerosolized pathogens, such as COVID-19, during respiratory suctioning. See Figure 4.14[15] for an example of PAPR in use.

Figure 4.14

PAPR

Resident Considerations During Isolation Precautions

There are a lot of things to consider when preventing the spread of infection among residents, staff, equipment, and surfaces. It is important to think about the tasks you will be performing for residents and determine ahead of time what you might be exposed to in order to select the appropriate PPE. The perspective and needs of clients placed in isolation precautions should also be considered. PPE makes communication more difficult by hiding facial expressions and making hearing more difficult, and therapeutic touch is less personal when wearing gloves. Caregivers often spend less time interacting with clients in transmission-based precautions due to the labor intensiveness of putting on and taking off PPE, resulting in clients often developing feelings of loneliness and social isolation due to less frequent interactions. Try to keep the resident’s routine as normal as possible and apply extra effort to interact with the client.

When transporting a client with transmission-based precautions within a facility, keep these principles in mind[16]:

- Limit transport for essential purposes only, such as diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the patient’s room.

- When transporting, use appropriate barriers on the patient consistent with the route and risk of transmission. For example, for a resident with a skin infection with MRSA, be sure the area is covered.

- Notify health care personnel in the receiving area of the impending arrival of the patient and of the precautions necessary to prevent transmission.

References

- 1.

- 2.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 3.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 4.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 5.

- “poster-how-to-remove-gloves.pdf” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www

.cdc.gov/vhf /ebola/resources/posters.html ↵. - 6.

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /guidelines /isolation/index.html ↵. [PMC free article: PMC7119119] [PubMed: 18068815] - 7.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 8.

- 9.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 10.

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control Practices for the Interprofessional Learner by Hughes, Kenmir, St-Amant, Cosgrove, & Sharpe and is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵.

- 11.

- “IMG_2021-scaled” and “IMG_2026-scaled” by unknown author are licensed under CC BY-NC-4.0. Access for free at https:

//ecampusontario .pressbooks.pub/introductiontoipcp /chapter/eye-protection/ ↵. - 12.

- “Screen-Shot-2021-05-05-at-3.57.19-PM” and “Screen-Shot-2021-05-05-at-3.57.41-PM” by unknown author are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Access for free at https:

//ecampusontario .pressbooks.pub/introductiontoipcp /chapter/masks/ ↵. - 13.

- “fs-facemask-dos-donts.pdf” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www

.cdc.gov/coronavirus /2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html ↵. - 14.

- “fs-respirator-on-off.pdf” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www

.cdc.gov/coronavirus /2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html ↵. - 15.

- 16.

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www

.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol /guidelines /isolation/index.html ↵. [PMC free article: PMC7119119] [PubMed: 18068815]

4.6. BLOOD-BORNE PATHOGEN STANDARD

Blood-borne pathogens are infectious microorganisms in blood and body fluids that can cause disease. These pathogens include, but are not limited to, hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Workers in many health-related occupations, including nursing assistants and other health care personnel, are at risk for exposure to blood-borne pathogens.

Needlesticks and other sharps-related injuries may expose workers to blood-borne pathogens. As a nursing assistant, your highest risk for blood-borne exposure is during shaving and any related disposal of the razor. Typically, residents use electric razors that have low risk of causing any open cuts, but you should always wear gloves when shaving a resident. Any disposable razor or objects that can cause a break in the skin, such as broken glass or needles, should be disposed of in a sharps container.[1] See Figure 4.15[2] for an image of a sharps container.

Figure 4.15

Sharps Container

Health care employers must follow OSHA’s guidelines for handling blood called the “Blood-borne Pathogens Standard.” If you handle a spill of blood or body fluids, you should wear a face shield, gown, and gloves. You should receive training during your orientation at an agency on how to properly handle a blood spill and the PPE and cleaning solutions available. See Figure 4.16[3] for an image of a typical blood spill kit.

Figure 4.16

Blood Spill Kit

If you do experience an exposure to a patient’s blood or body fluids, follow agency policy and wash/flush the area and notify the nurse supervisor. Part of OSHA’s “Blood-borne Pathogens Standard” is to complete a postexposure assessment to determine if additional medical treatment is required. It is extremely important that this assessment occurs immediately after your exposure. The standard also requires your employer to offer the vaccine series for hepatitis B and hepatitis C at no cost to you if you have not previously received them.

To read more information on OSHA’s Blood-borne Pathogens Standard, visit OSHA’s FactSheet PDF.

References

- 1.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.). Bloodborne pathogens and needlestick prevention. United States Department of Labor. https://www

.osha.gov /bloodborne-pathogens ↵. - 2.

- 3.

4.7. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF INFECTION

Nursing assistants spend a great deal of time with clients, so it is important to recognize early signs and symptoms of infection and report them to the nurse. While there are specific symptoms associated with specific types of infection, there are some general symptoms that can occur with all infections. These general symptoms include a feeling of malaise (i.e., a feeling of discomfort, illness, or lack of well-being), headache, fever, and lack of appetite.

A fever is a common sign of inflammation and infection. A temperature of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees F) is generally considered a low-grade fever, and a temperature of 38.3 degrees Celsius (101 degrees F) is considered a fever. Fever is part of the body’s nonspecific immune response and can be beneficial in destroying pathogens. However, extremely elevated temperatures can cause cell and organ damage, and prolonged fever can cause dehydration.

Infection raises the metabolic rate, which causes an increased heart rate. The respiratory rate may also increase as the body rids itself of carbon dioxide created during increased metabolism. If either of these conditions are noted, they should be reported to the nurse right away.

As an infection develops, the lymph nodes that drain that area often become enlarged and tender. The swelling indicates the lymph nodes are fighting the infection.

If a skin infection is developing, general signs of inflammation, such as redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness, will occur at the site. As white blood cells migrate to the site of infection, yellow or green drainage (i.e., purulent drainage) may occur.

Some viruses, bacteria, and toxins cause gastrointestinal inflammation, resulting in loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

See Table 4.7 for a comparison of expected findings in body systems versus unexpected findings that can indicate an infection and require notification of the nurse and/or health care provider.

Table 4.7

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings Related to Infection[1]

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings to Report to the Nurse |

|---|---|---|

| Vital Signs | Within normal range | New temperature over 100.4 F or 38 C or lower than the patient’s normal. |

| Neurological | Within baseline level of consciousness | New confusion and/or worsening level of consciousness. |

| Wound or Incision | Progressive healing of a wound with no signs of infection | New redness, warmth, tenderness, or purulent drainage from a wound. |

| Respiratory | No cough or production of sputum | New cough and/or productive cough of purulent sputum. New shortness of breath. |

| Genitourinary | Urine clear and light yellow without odor | Malodorous, cloudy, or bloody urine, with increased frequency, urgency, or pain with urination. |

| Gastrointestinal | Good appetite and food intake; feces formed and brown | Loss of appetite. Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Discolored or unusually malodorous feces. |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS indicating a possible life-threatening infection (called sepsis) requiring immediate notification of the nurse: Two or more of the following criteria in a patient with an existing infection: • Body temperature over 38 or under 36 degrees Celsius • Heart rate greater than 90 beats/minute • Respiratory rate greater than 20 |

Other Considerations

The effectiveness of the immune system gradually decreases with age, making older adults more vulnerable to infection. Early detection of infection can be challenging in older adults because they may not have a fever, but instead develop subtle changes like new confusion or weakness that may result in a fall. The most common infections in older adults are urinary tract infections (UTI), pneumonia, influenza, and skin infections.[2]

References

- 1.

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www

.hhs.gov/oidp /topics/health-care-associated-infections/index.html ↵. - 2.

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www

.hhs.gov/oidp /topics/health-care-associated-infections/index.html ↵.

4.8. SKILLS CHECKLIST: HAND HYGIENE WITH SOAP AND WATER

- 1.

Gather/Ensure Adequate Supplies: Soap and paper towels

- 2.

Procedure Steps:

- Remove jewelry according to agency policy; push your sleeves above your wrists.

- Turn on the water and adjust the flow so that the water is warm. Wet your hands thoroughly, keeping your hands and forearms lower than your elbows. Avoid splashing water on your uniform.

- Apply a palm-sized amount of hand soap.

- Perform hand hygiene using plenty of lather and friction for at least 15 seconds:

- Rub hands palm to palm

- Rub back of right and left hand (fingers interlaced)

- Rub palm to palm with fingers interlaced

- Perform rotational rubbing of left and right thumbs

- Rub your fingertips against the palm of your opposite hand

- Rub wrists

- Repeat sequence at least two times

- Keep fingertips pointing downward throughout

- Clean under your fingernails with disposable nail cleaner (if applicable).

- Wash for a minimum of 20 seconds.

- Keep your hands and forearms lower than your elbows during the entire washing.

- Rinse your hands with water, keeping your fingertips pointing down so water runs off your fingertips. Do not shake water from your hands.

- Do not lean against the sink or touch the inside of the sink during the hand-washing process.

- Dry your hands thoroughly from your fingers to wrists with a paper towel or air dryer.

- Dispose of the paper towel(s).

- Use a new paper towel to turn off the water.

- Dispose of the paper towel.

View a YouTube video[1] of an instructor demonstrating hand hygiene with soap and water:

References

- 1.

- Chippewa Valley Technical College. (2022, December 3). Hand Hygiene With Soap and Water. [Video]. YouTube. Video licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://youtu

.be/w29Ad7Cmsxo ↵.

4.9. SKILLS CHECKLIST: HAND HYGIENE WITH ALCOHOL-BASED HAND SANITIZER

- 1.

Gather Supplies: Antiseptic hand rub

- 2.

Procedure Steps:

- Remove jewelry according to agency policy; push your sleeves above your wrists.

- Apply enough product into the palm of one hand and enough to cover your hands thoroughly per product directions.

- Rub your hands together, covering all surfaces of your hands and fingers with antiseptic until the alcohol is dry (a minimum of 30 seconds):

- Rub hands palm to palm

- Rub back of right and left hand (fingers interlaced)

- Rub palm to palm with fingers interlaced

- Perform rotational rubbing of left and right thumbs

- Rub your fingertips against the palm of your opposite hand

- Rub your wrists

- Repeat hand sanitizing sequence a minimum of two times.

- Repeat hand sanitizing sequence until the product is dry.

View a YouTube video[1] of an instructor demonstrating hand hygiene with alcohol-based hand sanitizer:

References

- 1.

- Chippewa Valley Technical College. (2022, December 3). Hand Hygiene With Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer. [Video]. YouTube. Video licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://youtu

.be/rTuO8SYYfNo ↵.

4.10. SKILLS CHECKLIST: REMOVING GLOVES

- 1.

Procedure Steps:

- Using either hand, grasp the glove at the palm of the other hand.

- Remove the glove.

- Grasp the empty glove within the palm of the gloved hand.

- Using the index and middle fingers of the bare hand, slide fingers underneath the remaining glove at the wrist.

- Turn the remaining glove inside out while containing the first glove inside.

- Discard in an appropriate receptacle.

- Perform hand hygiene.

View a YouTube video[1] of an instructor demonstrating removing gloves:

Figure 4.17[2] Glove Removal

Figure 4.17

Glove Removal

References

- 1.

- Chippewa Valley Technical College. (2022, December 3). Removing Gloves. [Video]. YouTube. Video licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://youtu

.be/nYDB6b3K-MY ↵. - 2.

- “Ch.5-Taking-off-PPE-–-Step-8,” Ch.5-Taking-off-PPE-Step-1a-.png,” “Ch.5-Taking-off-PPE-Step-1c.png,” “Ch.5-Taking-off-PPE-Step-1d,” “Ch.5-Taking-off-PPE-Step-1e.png,” and “Ch.5-Taking-off-PPE-Step-2.png” by unknown author are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Access for free at https:

//ecampusontario .pressbooks.pub/introductiontoipcp /chapter /putting-it-all-together-putting-on-and-taking-off-full-ppe/ ↵.

4.11. SKILLS CHECKLIST: DONNING/DOFFING PPE WITHOUT A MASK

- 1.

Gather Supplies: Gown, gloves, and alcohol-based sanitizer

- 2.

Procedure Steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Face the back opening of the gown.

- Unfold the gown.

- Put your arms into the sleeves.

- Secure the neck opening behind your head.

- Secure the waist, making sure that the back flaps overlap each other and cover your clothing as completely as possible.

- Put on gloves.

- Ensure the gloves overlap the gown sleeves at the wrist.

- When care has been completed and before leaving the room, remove the gloves BEFORE removing the gown.

- Remove the gloves, turning them inside out.

- Dispose of the gloves in the appropriate container.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Unfasten the gown at the neck.

- Unfasten the gown at the waist.

- Remove the gown starting at the top of the shoulders, turning it inside out and folding soiled area to soiled area.

- Dispose of the gown in an appropriate container.

- Perform hand hygiene.

View a YouTube video[1] of an instructor demonstrating donning/doffing PPE without a mask:

References

- 1.

- Chippewa Valley Technical College. (2022, December 3). Donning/Doffing PPE Without a Mask. [Video]. YouTube. Video licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://youtu

.be/yP1eIqGJSS8 ↵.

4.12. SKILLS CHECKLIST: DONNING/DOFFING PPE WITH A MASK AND FACE SHIELD OR GOGGLES

- 1.

Gather Supplies: Gown, mask, face shield, goggles, and alcohol-based sanitizer

- 2.

Procedure Steps:

- Face the back opening of the gown.

- Unfold the gown.

- Put your arms into the sleeves.

- Secure the neck opening at the back of your neck.

- Secure the waist, making sure that the back flaps overlap each other and covering your clothing as completely as possible.

- Put on a mask and, if needed, goggles or face shield.

- Put on gloves.

- Ensure the gloves overlap the gown sleeves at the wrist.

- When care is complete and before leaving the room, remove the gloves BEFORE removing the gown.

- Remove the gloves, turning them inside out.

- Dispose of the gloves in the appropriate container.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Remove any goggles or face shield and place in the appropriate receptacle.

- Unfasten the gown at the neck.

- Unfasten the gown at the waist.

- Remove the gown starting at the top of the shoulders, turning it inside out and folding soiled area to soiled area.

- Dispose of the gown in an appropriate container.

- Remove the mask by grasping loop behind ear or untying at back of head.

- Perform hand hygiene.

Review the Sequence for putting on personal protective equipment PDF handout[1] from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with current recommendations for putting on and removing PPE.

View a YouTube video[2] of an instructor demonstrating donning/doffing PPE with a mask and face shield or goggles:

References

- 1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Sequence for putting on personal protective equipment [Handout]. https://www

.cdc.gov/hai /pdfs/ppe/ppe-sequence.pdf ↵. - 2.

- Chippewa Valley Technical College. (2022, December 3). Donning/Doffing PPE With a Mask and Face Shield or Goggles. [Video]. YouTube. Video licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://youtu

.be/H-rXxFkmWBY ↵.

IV. GLOSSARY

- Airborne precautions

Transmission-based precautions used for clients with diagnosed or suspected pathogens spread by very small airborne particles from nasal and oral secretions that can float long distances through the air, such as measles and tuberculosis.

- Blood-borne pathogens

Infectious microorganisms in blood and body fluids that can cause disease, including hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Carrier

An individual who is colonized with an infectious agent.

- Chain of infection

The process of how an infection spreads based on six links of transmission: Infectious Agent, Reservoir, Portal of Exit, Modes of Transmission, Portal of Entry, and Susceptible Host.

- Colonization

A condition when a person carries an infectious agent but is not symptomatic or ill.

- Contact precautions

Transmission-based precautions used for clients with known or suspected infections transmitted by touch such as C-difficile (C-diff), methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin resistant enterococcus (VRE), or norovirus.

- Disinfection

The removal of microorganisms. However, disinfection does not destroy all spores and viruses.

- Doff

Take off personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Don

Put on personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Droplet precautions

Transmission-based precautions used for clients with a diagnosed or suspected pathogen that is spread in small droplets from sneezing or in oral and nasal secretions, such as influenza or pertussis.

- Eye protection

Face shields, visors attached to masks, and goggles that are used to protect the eyes from blood or body fluids.

- Fever

A temperature of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees F).

- Hand hygiene

The process of removing, killing, or destroying microorganisms or visible contaminants from the hands. There are two hand-hygiene techniques: handwashing with soap and water and the use of alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR).

- Healthcare-associated infection (HAI)

An infection that develops in an individual after admission to a health care facility or undergoing a medical procedure.

- Infection control

Methods to prevent or stop the spread of infections in health care settings.

- Infectious agent

Microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites that can cause infectious disease.

- Inflammation

Redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness associated with early signs of infection.

- Isolation gowns

Protective garments worn to protect clothing from the splashing or spraying of body fluids and reduce the transmission of microorganisms.

- Malaise

A feeling of discomfort, illness, or lack of well-being that is often associated with infection.

- Masks

Protective coverings worn by health care providers to protect the mucous membranes of their nose and mouth.

- Medical asepsis

Techniques used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another but do not completely eliminate microorganisms.

- Mode of transmission

The way an infectious agent travels to other people and places.

- Moments of hand hygiene

Appropriate times during patient care to perform hand hygiene, including immediately before touching a patient; before performing an aseptic task; before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site; after touching a patient or their immediate environment; after contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use); and immediately after glove removal.

- Nonspecific defenses

Generic barriers that prevent pathogens from entering the body, including physical, mechanical, or chemical barriers.

- PAPR

An air-purifying respirator that uses a blower to force air through filter cartridges or canisters into the breathing zone of the wearer. This process creates an air flow inside either a tight-fitting facepiece or loose-fitting hood or helmet, providing a higher level of protection against aerosolized pathogens.

- Perineal care

Cleansing the genital and rectal areas of the body.

- Personal protective equipment (PPE)

Specialized clothing or equipment used to prevent the spread of infection, including gloves, gowns, facial protection (masks and eye protection), and respirators.

- Portal of entry

The route by which an infectious agent enters a new host.

- Portal of exit

The route by which an infectious agent escapes or leaves the reservoir.

- Purulent drainage

Yellow, green, or brown drainage associated with signs of infection.

- Reservoir

The host in which infectious agents live, grow, and multiply.

- Respirator masks

Masks with N95 or higher filtration worn by health care professionals to prevent inhalation of infectious small airborne particles.

- Respiratory hygiene

Methods to prevent the spread of respiratory infections, including coughing/sneezing into the inside of one’s elbow or covering one’s mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and promptly disposing of used tissues. Hand hygiene should be immediately performed after contact with one’s respiratory secretions. A coughing person should also wear a surgical mask to contain secretions.

- Specific defenses

Immune system processes like white blood cells attacking particular pathogens.

- Standard precautions

Precautions used by health care workers during client care when contact or potential contact with blood or body fluids may occur based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These precautions reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect patients from potential transmission of infectious organisms.

- Sterilization

A process used on equipment and the environment that destroys all pathogens, including spores and viruses. Sterilization methods include steam, boiling water, dry heat, radiation, and chemicals.

- Surgical asepsis

The absence of all microorganisms during any type of invasive procedure; used for equipment used during invasive procedures, as well as the environment.

- Susceptible host

A person at elevated risk of developing an infection when exposed to an infectious agent.

- Transmission-based precautions

Specific types of personal protective equipment (PPE) and practices used with clients with specific types of infectious agents based on the pathogen’s mode of transmission.

- INTRODUCTION TO ADHERE TO PRINCIPLES OF INFECTION CONTROL

- CHAIN OF INFECTION

- DEFENSES AGAINST TRANSMISSION OF INFECTION

- PRECAUTIONS USED TO PREVENT THE SPREAD OF INFECTION

- PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE)

- BLOOD-BORNE PATHOGEN STANDARD

- SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF INFECTION

- SKILLS CHECKLIST: HAND HYGIENE WITH SOAP AND WATER

- SKILLS CHECKLIST: HAND HYGIENE WITH ALCOHOL-BASED HAND SANITIZER

- SKILLS CHECKLIST: REMOVING GLOVES

- SKILLS CHECKLIST: DONNING/DOFFING PPE WITHOUT A MASK

- SKILLS CHECKLIST: DONNING/DOFFING PPE WITH A MASK AND FACE SHIELD OR GOGGLES

- LEARNING ACTIVITIES

- GLOSSARY

- Chapter 4: Adhere to Principles of Infection Control - Nursing AssistantChapter 4: Adhere to Principles of Infection Control - Nursing Assistant

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...