Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Reuter-Sandquist M; Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN); Ernstmeyer K, Christman E, editors. Nursing Assistant [Internet]. Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College; 2022.

1.1. INTRODUCTION TO COMMUNICATE PROFESSIONALLY WITHIN A HEALTH CARE SETTING

Learning Objectives

• Interact professionally with clients, families, and coworkers

• Display appropriate verbal and nonverbal communication skills in the health care setting

• Establish therapeutic relationships with clients and their family members

• Respond to clients exhibiting disruptive behaviors

• Respond to aggressive behavior

• Establish effective working relationships with supervisors and peers

• Demonstrate effective reporting and documentation

• Assist clients to meet spiritual needs

• Adapt care and communication to meet the psychological needs of the aging client

• Demonstrate empathy for the emotional needs and mental health of diverse clients

• Apply effective coping strategies

Effective communication is a vital skill for nursing assistants. Nursing assistants communicate professionally with patients and other health care team members throughout every shift. This chapter will review the communication process, discuss strategies for adapting communication based on the needs of the client and health care team, and introduce guidelines for documentation and reporting.

1.2. THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

Communication is a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior.[1] In the health care setting, good communication is the foundation to trusting relationships that improve client outcomes. It is the gateway to providing holistic care. Holistic care addresses a client’s physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs.[2] The communication process involves a sender, the message, and a receiver. See Figure 1.1[3] for an illustration of the communication process.

Figure 1.1

The Communication Process

Verbal Messages

There are many aspects of the communication process that can alter the delivery and interpretation of the message. These aspects relate to the language and experience of both the sender and receiver, referred to as semantics. People typically make reference to things they are familiar with, including landmarks, popular culture, and slang. Barriers can occur even when both parties in the conversation speak the same language. For example, if you asked a person who has never used the Internet to “Google it,” they would have no idea what that means.

Nonverbal Messages

Nonverbal messages, also referred to as body language, greatly impact the conversational process. Nonverbal communication includes body language and facial expressions, tone of voice, and pace of the conversation. See Figure 1.2[4] for an illustration of body language communicating a message. Nonverbal communication can have a tremendous impact on the communication experience and may be much more powerful than the verbal message itself. You may have previously learned that 80% of communication is nonverbal communication. The importance of nonverbal communication during conversation has been broken down further, estimating that 55% of communication is body language, 38% is tone of voice, and 7% is the actual words spoken.[5] If the sender or receiver appears disinterested or distracted, the message or interpretation may become distorted or missed.

Figure 1.2

Body Language

Health care professionals assess receivers’ preferred methods of communication and individual characteristics that might influence communication and then adapt communication to meet the receivers’ needs. For example, nursing assistants adapt verbal instructions for adult patients with cognitive disabilities. Although the information provided might be similar to that provided to a patient without disabilities, the way the information is provided is adapted based on the patient’s developmental level. A nursing assistant may ask a cognitively intact person, “What do you want for lunch?” but adapt this information for someone with impaired cognitive function by offering a choice, such as “Do you want a sandwich or soup for lunch?” This adaptation allows the cognitively impaired patient to make a choice without being confused or overwhelmed by too many options.[6] Read more about developmental levels in the “Human Needs and Developmental Stages” section of this chapter.

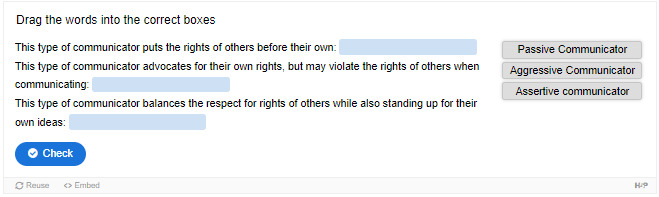

Communication Styles

In addition to using verbal and nonverbal communication, people communicate with others using one of three styles. A passive communicator puts the rights of others before their own. Passive communicators tend to be apologetic or sound tentative when they speak and often do not speak up if they feel as if they are being wronged. Aggressive communicators, on the other hand, come across as advocating for their own rights despite possibly violating the rights of others when communicating. They tend to communicate in a way that tells others their feelings don’t matter. Assertive communicators respect the rights of others while also standing up for their own ideas and rights when communicating. An assertive person is direct, but not insulting or offensive.[7]

Assertive communication refers to a way of conveying information that describes the facts and the sender’s feelings without disrespecting the receiver’s feelings. Assertive communication is different from aggressive communication because it uses “I” messages, such as “I feel…,” “I understand…,” or “Help me to understand…,” to address issues instead of using “you” messages that can cause the receiver to feel as though they are being verbally attacked. Using assertive communication is an effective way to solve problems with patients, coworkers, and health care team members. For example, instead of using aggressive communication to say to a coworker, “You always leave your patients’ rooms a mess! I dread following you on the next shift,” an assertive communicator would use “I” messages. The assertive communicator might say, “I feel frustrated spending the first part of my shift decluttering patients’ rooms. Help me understand the reasons why you don’t empty the wastebaskets and clean up the rooms by the end of your shift.”[8]

Overcoming Communication Barriers

It is important to reflect on personal factors that influence your ability to communicate with others effectively. There are many factors that can distort the message you are trying to communicate, resulting in your message not being perceived by the receiver in the way you intended. When communicating, it is important to seek feedback that your message is clearly understood.[9] Nursing assistants must be aware of these potential barriers and try to reduce their impact by continually seeking feedback and checking understanding. Review common communication barriers in the following box.

Common Barriers to Communication in Health Care[10]

- Jargon: Avoid using medical terminology, complicated wording, or unfamiliar words. When communicating with patients, explain information in common language that is easy to understand. Consider any generational, geographical, or background information that may change the perception or understanding of your message.

- Lack of attention: It is easy to become task-centered rather than person-centered when caring for multiple residents. When entering a patient’s room, remember to use preprocedural steps and mindfully focus on the person in front of you to give them your full attention. Patients should feel as if they are the center of your attention when you are with them, no matter how many other things you have going on.

- Noise and other distractions: Health care environments can be very noisy with people talking in the room or hallway, the TV blaring, alarms beeping, and pages occurring overhead. Create a calm, quiet environment when communicating with patients by closing doors to the hallway, reducing the volume of the TV, or moving to a quieter area, if possible.

- Light: A room that is too dark or too light can create communication barriers. Ensure the lighting is appropriate according to the patient’s preference.

- Hearing and speech problems: If your patient has hearing or speech problems, implement strategies to enhance communication, including assistive devices such as eyeglasses, hearing aids, and any communication aids such as whiteboards, photobooks, or microphones.

- Language differences: If English is not your patient’s primary language, it is important to seek a medical interpreter and provide written handouts in the patient’s preferred language when possible. Most agencies have access to an interpreter service available by phone if they are not available on-site.

- Differences in cultural beliefs: The norms of social interaction vary greatly in different cultures, as well as the ways that emotions are expressed. For example, the concept of personal space varies among people from different cultural backgrounds. Some people prefer to stand very close to one another when speaking whereas others prefer a distance of a few feet. Additionally, some patients are stoic about pain whereas others are more verbally expressive when in pain.

- Psychological barriers: Psychological states of the sender and the receiver affect how the message is sent, received, and perceived. Consider what the receiver may be experiencing in the health care setting and what may change your delivery of your message. Being rushed, distracted, and overwhelmed are just a few things that can affect your message and its understanding.

- Physiological barriers: It is important to be aware of patients’ potential physiological barriers when communicating. For example, if a patient is in pain, they are less likely to hear and remember what was said. If the patient is receiving pain medication, be aware these medications may alter their comprehension and response.

- Physical barriers for nonverbal communication: Providing information via email or text is often less effective than face-to-face communication. The inability to view the nonverbal communication associated with a message, such as tone of voice, facial expressions, and general body language, often causes misinterpretation of the message by the receiver. When possible, it is best to deliver important information to others using face-to-face communication so that nonverbal communication is included with the message.

- Differences in perceptions and viewpoints: Everyone has their own beliefs and perspectives and wants to feel “heard.” When patients feel their beliefs or perspectives are not valued, they often become disengaged from the conversation or their plan of care. Information should be provided in a nonjudgmental manner, even if the patient’s perspectives, viewpoints, and beliefs are different from your own.

References

- 1.

- 2.

- Jasemi, M., Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., & Keogh, B. (2017). A concept analysis of holistic care by hybrid model. Indian Journal of Palliative Care , 23(1), 71–80. ↵ 10.4103/0973-1075.197960 . [PMC free article: PMC5294442] [PubMed: 28216867] [CrossRef]

- 3.

- “Communication Process” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 4.

- “Boulder

_Worldcup_Vienna _29-05-2010a_semifinals090 _Akiyo_Noguchi, _Anna_Stöhr.jpg” by Manfred Werner - Tsui is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵. - 5.

- Thompson, J. (2011). Is nonverbal communication a numbers game? Psychology Today. https://www

.psychologytoday .com/us/blog/beyond-words /201109/is-nonverbal-communication-numbers-game ↵. - 6.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 7.

- 8.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 9.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 10.

- SkillsYouNeed. (n.d.). Barriers to effective communication. https://www

.skillsyouneed .com/ips/barriers-communication .html ↵.

1.3. COMMUNICATION WITHIN THE HEALTH CARE TEAM

Communicating With Staff

The resident is at the center of the health care team. As a nursing assistant, most of your duties will involve interaction regarding nursing services among other CNAs, LPNs, and RNs. It is important to establish a good relationship with coworkers to ensure quality resident care. Improper communication can affect the team’s ability to provide holistic care. The health care team will be discussed further in Chapter 2.

Good communication starts by respecting those you work with and using the communication skills previously discussed to grow a trusting relationship. Knowing and fulfilling your duties, documenting and reporting the completion of these duties, and functioning in a consistent and dependable manner are keys to creating strong, professional relationships within your team.

These expectations for good communication may seem challenging as an inexperienced nursing assistant, but they can be achieved by organizing your responsibilities and managing your time. This begins by arriving on time for your shift, being dressed appropriately, being prepared to start working when your shift starts, and reviewing your assigned residents’ plans of care at the beginning of the shift. Items to review in the plan of care include the following:

- Resident’s name and location

- Activity level and transfer status

- Assistance required for activities of daily living (ADLs)

- Diet and fluid orders (see Chapter 6 for more information)

- Elimination needs

Transfer status refers to the assistance the patient requires to be moved from one location to another, such as from the bed to a chair. Activities of daily living (ADLs) are daily basic tasks that are fundamental to everyday functioning (e.g., hygiene, elimination, dressing, eating, ambulating/moving). Diet and fluid orders refer to what the resident is permitted to eat and drink. Elimination needs refer to assistance the resident requires for urinating and passing stool. For example, a resident requires assistance to the toilet and uses incontinence pads.

After reviewing the cares you will be providing to your assigned patients during your shift, discuss a timeline with your coworkers that meets residents’ schedules and allows for the coordination of cares that require more than one caregiver. For example, one resident may require a two-person assist when transferring from the bed to the chair. Schedules for activities, treatments, labs, appointments, or other services should also be reviewed so that cares can be organized around these schedules.

As resident cares are completed, they must be documented in a timely manner and reported to nursing staff. Prepare a concise report to share with the nurse for each of your assigned clients. The report should include the time cares were provided and any observations or changes noted in the resident. Read more about documentation and reporting in the “Documenting and Reporting” section at the end of this chapter.

Communicating With the Client, Families, and Loved Ones

Therapeutic communication is a type of professional communication used with patients. It is defined as the purposeful, interpersonal, information-transmitting process through words and behaviors based on both parties’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills that leads to patient understanding and participation.[1] Therapeutic communication techniques have been used by nurses since Florence Nightingale, who insisted on the importance of building trusting relationships with patients. She believed in the therapeutic healing that results from nurses’ presence with patients.[2] Since then, several professional nursing associations have highlighted therapeutic communication as one of the most vital elements in nursing.[3] Nursing assistants also implement therapeutic communication with patients. Read an example of a nursing student effectively using therapeutic communication with patients in the following box.

Figure 1.3

Attending Behaviors

An Example of Nursing Student Using Therapeutic Communication[4],[5]

Ms. Z. is a nursing student who enjoys interacting with patients. When she goes to patients’ rooms, she greets them and introduces herself and her role in a calm tone. She kindly asks patients about their problems and notices their reactions. She does her best to solve their problems and answer their questions. Patients perceive that she wants to help them. She treats patients professionally by respecting boundaries and listening to them in a nonjudgmental manner. She addresses communication barriers and respects patients’ cultural beliefs. She notices patients’ health literacy and ensures they understand her messages and patient education. As a result, patients trust her and feel as if she cares about them, so they feel comfortable sharing their health care needs with her.

There are several components included in therapeutic communication. The health care professional uses active listening and attending behaviors to demonstrate they are interested in understanding what the patient is saying. Touch is used to professionally communicate caring, and specific therapeutic techniques are used to encourage the patient to share their thoughts, concerns, and feelings.

Active Listening and Attending Behaviors

Listening is obviously an important part of communication. A well-known phrase from a Greek philosopher named Epictetus is, “We have two ears and one mouth so we can listen twice as much as we speak.” It is important to actively listen to patients and not use competitive or passive listening. Competitive listening occurs when we are primarily focused on sharing our own point of view instead of listening to someone else. Passive listening occurs when we are not interested in listening to the other person or we assume we correctly understand what the person is communicating without verifying their message. During active listening, we communicate verbally and nonverbally that we are interested in what the other person is saying and also verify our understanding with the speaker. For example, an active listening technique is to restate what the person said and verify our understanding is correct, such as, “I hear you saying you are hesitant to go to physical therapy because you are afraid of falling. Is that correct?” This feedback process is the main difference between passive listening and active listening.[6]

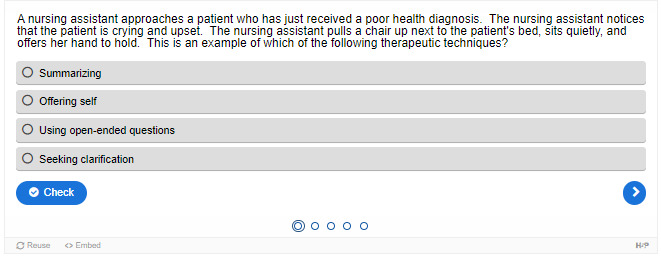

Touch

Touch is a powerful way to professionally communicate caring and compassion if done respectfully while being aware of the patient’s cultural beliefs. NAs commonly use professional touch when assessing, expressing concern, or comforting patients. For example, simply holding a patient’s hand during a painful procedure can be very effective in providing comfort. See Figure 1.4[7] for an image of a nurse using touch as a therapeutic technique when caring for a patient.

Figure 1.4

Using Touch as a Therapeutic Technique

Therapeutic Communication Techniques

Therapeutic communication techniques are specific methods used to provide patients with support and information while focusing on their concerns. Nursing assistants help patients complete activities of daily living and meet goals in their plan of care based on their needs, values, skills, and abilities. It is important to recognize the autonomy of the patient to make their own decisions, maintain a nonjudgmental attitude, and avoid interrupting. Depending on the developmental stage and educational needs of the patient, appropriate terminology should be used to promote patient understanding and rapport. When using therapeutic communication, health care professionals often ask open-ended questions, repeat information, or use silence to prompt patients to process their concerns. Table 1.3a describes a variety of therapeutic communication techniques.

Table 1.3a

Therapeutic Communication Techniques[8]

| Therapeutic Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Active Listening | By using nonverbal and verbal cues such as nodding and saying, “I see,” health care professionals can encourage patients to continue talking. Active listening involves showing interest in what patients have to say, acknowledging that you’re listening and understanding, and engaging with them throughout the conversation. General leads such as “What happened next?” can be used to guide the conversation or propel it forward. |

| Using Silence | At times, it’s useful to not speak at all. Deliberate silence can give patients an opportunity to think through and process what comes next in the conversation. It may also give them the time and space they need to broach a new topic. |

| Providing Acceptance | Sometimes it is important to acknowledge a patient’s message and affirm they’ve been heard. Acceptance isn’t necessarily the same thing as agreement; it can be enough to simply make eye contact and say, “I hear what you are saying.” Patients who feel their health care professionals are listening to them and taking them seriously are more likely to be receptive to care. |

| Giving Recognition | Recognition acknowledges a patient’s behavior and highlights it. For example, saying something such as “I noticed you ate all of your breakfast today” draws attention to the action and encourages it. |

| Offering Self | Hospital stays can be lonely and stressful at times. When health care professionals make time to be present with their patients, it communicates they value them and are willing to give them time and attention. Offering to simply sit with patients for a few minutes is a powerful way to create a caring connection. |

| Giving Broad Openings/Open-Ended Questions | Therapeutic communication is often most effective when patients direct the flow of conversation and decide what to talk about. For example, giving patients a broad opening such as “What’s on your mind today?” or “What would you like to talk about?” is a good way to allow patients an opportunity to discuss what’s on their mind. |

| Seeking Clarification | Similar to active listening, asking patients for clarification when they say something confusing or ambiguous is important. Saying something such as “I’m not sure I understand. Can you explain more to me?” helps health care professionals ensure they understand what’s actually being said and can help patients process their ideas more thoroughly. |

| Placing the Event in Time or Sequence | Asking questions about when certain events occurred in relation to other events can help patients (and health care professionals) get a clearer sense of the whole picture. It forces patients to think about the sequence of events and may prompt them to remember something they otherwise wouldn’t. |

| Making Observations | Making observations about the appearance, demeanor, or behavior of patients can help draw attention to areas that may indicate a problem. For example, making an observation that they haven’t been eating much may lead to the discovery of a new symptom. |

| Encouraging Descriptions of Perception | For patients experiencing sensory issues or hallucinations, it can be helpful to ask about these perceptions in an encouraging, nonjudgmental way. Phrases such as “What do you hear now?” or “What do you see?” give patients a prompt to explain what they’re perceiving without casting their perceptions in a negative light. |

| Encouraging Comparisons | Patients often draw upon previous experiences to deal with current problems. By encouraging them to make comparisons to situations they have coped with before, health care professionals can help patients discover solutions to their problems. |

| Summarizing | It is often useful to summarize what patients have said. This demonstrates you are listening and allows you to verify information. Ending a summary with a phrase such as “Does that sound correct?” gives patients explicit permission to make corrections if they’re necessary. |

| Reflecting | Patients often ask health care professionals for advice about what they should do about particular problems. Instead of offering advice, health care professionals can ask patients to reflect on what they think they should do, which encourages them to be accountable for their own actions and helps them come up with solutions themselves. |

| Focusing | Sometimes during a conversation, patients mention something particularly important. When this happens, health care professionals can focus on this statement and prompt patients to discuss it further. Patients don’t always have an objective perspective on what is relevant to their case, but as impartial observers, health care professionals may be able to pick out the topics on which to focus. |

| Confronting | Health care professionals should only use this technique after they have established trust and rapport with the client. In some situations, it can be vital to disagree with patients, present them with reality, or challenge their assumptions. Confrontation, when used correctly, can help patients break destructive routines or understand the state of their current situation. |

| Voicing Doubt | Voicing doubt can be a gentler way to call attention to incorrect or delusional ideas and perceptions of patients when appropriate. For example, when appropriate, a health care worker may say to a patient experiencing visual hallucinations, “I know you said you are seeing spiders on the walls, but I don’t see any spiders.” |

| Offering Hope and Humor | Because hospitals can be stressful places for patients, sharing hope that they can persevere through their current situation or lightening the mood with humor can quickly establish rapport. This technique can help move patients in a more positive state of mind. However, it is important to tailor humor to the patient’s sense of humor. |

In addition to the therapeutic techniques listed in Table 1.3a, health care professionals should genuinely communicate with patients with empathy. Communicating honestly, genuinely, and authentically is powerful. It opens the door to establishing true connections with others.[9] Communicating with empathy can be described as providing “unconditional positive regard.” Research has demonstrated that when health care professionals communicate with empathy, there is improved patient healing, reduced symptoms of depression, and decreased medical errors.[10]

Nontherapeutic Responses

Health care professionals must be aware of potential barriers to communication. In addition to the common communication barriers discussed in the “Communication Styles” subsection of this chapter, there are several nontherapeutic responses to avoid. These nontherapeutic responses often block the patient’s communication of their feelings or ideas. See Table 1.3b for a description of nontherapeutic responses.[11]

Table 1.3b

Nontherapeutic Responses[12]

| Nontherapeutic Response | Description |

|---|---|

| Asking Personal Questions | Asking personal questions that are not relevant to the situation is not professional or appropriate. Don’t ask questions just to satisfy your curiosity. For example, asking, “Why have you and Mary never married?” is not appropriate. A more therapeutic question would be, “How would you describe your relationship with Mary?” |

| Giving Personal Opinions | Giving personal opinions takes away the decision-making from the patient. Effective problem-solving must be accomplished by the patient and not the NA. For example, stating, “If I were you, I’d put your father in a nursing home” is not therapeutic. Instead, it is more therapeutic to say, “Let’s talk about what options are available to your father.” |

| Changing the Subject | Changing the subject when someone is trying to communicate with you demonstrates lack of empathy and blocks further communication. It seems to say that you don’t care about what they are sharing. For example, stating, “Let’s not talk about your insurance problems; it’s time for your walk now” is not therapeutic. A more therapeutic response would be, “After your walk, let’s talk more about your concerns about insurance so I can help find assistance for you.” |

| Stating Generalizations and Stereotypes | Generalizations and stereotypes can threaten relationships with patients. For example, it is not therapeutic to state a stereotype like, “Older adults are always confused.” It is better to focus on the patient’s concern and ask, “Tell me more about your concerns about your wife’s confusion.” |

| Providing False Reassurances | When a patient is seriously ill or distressed, it is tempting to offer false hope with statements such as “You’ll be fine,” or “Don’t worry; everything will be alright.” These comments tend to discourage further expressions of feelings by the patient. A more therapeutic response would be, “It must be difficult not to know what the surgeon will find. What can I do to help?” |

| Showing Sympathy | Sympathy focuses on the health care professional’s feelings rather than the patient. Saying “I’m so sorry about your amputation; I can’t imagine losing a leg” shows pity rather than trying to help the patient cope with the situation. A more therapeutic response would be, “The loss of your leg is a major change; how do you think this will affect your life?” |

| Asking “Why” Questions | It can be tempting to ask a patient to explain “why” they believe, feel, or act in a certain way. However, patients and family members can interpret “why” questions as accusations and become defensive. It is best to phrase a question by avoiding the word “why.” For example, instead of asking, “Why are you so upset?” it is better to rephrase the statement as, “You seem upset. What’s on your mind?” |

| Approving or Disapproving | Health care professionals should not impose their own attitudes, values, beliefs, and moral standards on patients or family members. Judgmental messages contain terms such as “should,” “shouldn’t,” “ought to,” “good,” “bad,” “right,” or “wrong.” Agreeing or disagreeing sends the subtle message that health care professionals have the right to make value judgments about the patient’s decisions. Approving implies that the behavior being praised is the only acceptable one, and disapproving implies that the patient must meet the listener’s expectations or standards. Instead, health care professionals should help the patient explore their own beliefs and decisions. For example, it is nontherapeutic to state, “You shouldn’t schedule elective surgery; there are too many risks involved.” A more therapeutic response would be, “So you are considering elective surgery. Tell me more about it…” This response gives the patient a chance to express their ideas or feelings without fear of being judged. |

| Giving Defensive Responses | When patients or family members express criticism, health care professionals should actively listen. Listening does not imply agreement. To discover reasons for the patient’s anger or dissatisfaction, health care professionals should listen without criticism, avoid being defensive or accusatory, and attempt to defuse anger. For example, it is not therapeutic to state, “No one here would intentionally lie to you.” Instead, a more therapeutic response would be, “You believe people have been dishonest with you. Tell me more about what happened.” (After obtaining additional information, the health care worker may decide to follow the chain of command at the agency and report the patient’s concerns to the nurse supervisor for follow-up.) |

| Providing Passive or Aggressive Responses | Passive responses serve to avoid conflict or sidestep issues, whereas aggressive responses provoke confrontation. Health care workers should use assertive communication. |

| Arguing | Challenging or arguing against patient perceptions denies that they are real and valid to the other person. They imply that the other person is lying, misinformed, or uneducated. The skillful health care professional can provide alternative information or present reality in a way that avoids argument. For example, it is not therapeutic to state, “How can you say you didn’t sleep a wink when I heard you snoring all night long!” A more therapeutic response would be, “You don’t feel rested this morning? Let’s talk about ways to improve your sleep so you feel more rested.” |

Strategies for Effective Communication

In addition to overcoming common communication barriers, using active listening and therapeutic communication techniques, and avoiding nontherapeutic responses, there are additional strategies for promoting effective communication when providing patient-centered care. Specific questions to ask patients are as follows[13]:

- What concerns do you have about your plan of care?

- What questions do you have about your daily routine?

- Did I answer your question(s) clearly, or is there additional information you would like?

Listen closely for feedback from patients. Feedback provides an opportunity to improve patient understanding, improve the patient-care experience, and provide high-quality care. Other suggestions for effective communication with clients include the following:

- Read the care plan carefully and access any social history available. If family members or friends visit and it seems appropriate, talk with them about the client without intruding or taking up a lot of their time together. This information helps you build trust and care for the client based on their preferences and life history. For example, you might learn the resident lived on a farm most of their life and enjoyed taking care of their horses. Striking up conversations about horses is a way to build rapport with this client.

- Review any changes in routine or in the plan of care for assisting with ADLs with the client to improve understanding and participation.

- If there are questions you can’t answer, be sure to report to the nurse so someone can follow up with the client. Check back with the client to ensure they have had their questions answered.

- Observe nonverbal communication from clients. Do they seem to interact during care, or is it something that they are merely tolerating and just trying to get through each day? Find an approach so they are comfortable with receiving care.

Adapting Your Communication

When communicating with patients, their family members, and other caregivers, note your audience and adapt your message based on characteristics such as age, developmental level, cognitive abilities, and any communication disorders. For patients with language differences, it is vital to provide trained medical interpreters when important information is communicated.

Adapting communication according to an individual’s age and developmental level includes the following strategies[14]:

- When communicating with children, speak calmly and gently. It is often helpful to demonstrate what will be done during a procedure on a doll or stuffed animal. To establish trust, try using play or drawing pictures.

- When communicating with adolescents, give freedom to make choices within established limits.

- When communicating with older adults, be aware of potential vision and hearing impairments that commonly occur and address these barriers accordingly. For example, if a patient has glasses and/or hearing aids, be sure these devices are in place before communicating.

Strategies for Communicating With Patients With Impaired Hearing, Vision, and Speech

In addition to adapting your communication to your audience, there are additional strategies to use with individuals who have impaired hearing, vision, or speech.

Impaired Hearing[15]

- Gain the person’s attention before speaking (e.g., through touch)

- Minimize background noise

- Position yourself 2-3 feet away from the patient

- Facilitate lip-reading by facing the person directly in a well-lit environment

- Use gestures, when necessary

- Listen attentively, allowing the person adequate time to process communication and respond

- Refrain from shouting at the person

- Ask the person to suggest strategies for improved communication (e.g., speaking toward a better ear, moving to well-lit area, and speaking in a lower-pitched tone)

- Face the person directly, establish eye contact, and avoid turning away mid-sentence

- Simplify language (e.g., do not use slang but do use short, simple sentences), as appropriate

- Read the care plan for information on the preferred method of communicating (whiteboards, pictures, etc.)

- Assist the person using any devices such as hearing aids or voice amplifiers

- Report any changes to the nurse

Impaired Vision[16]

- Identify yourself when entering the person’s space

- Ensure the patient’s eyeglasses are cleaned and stored properly when not in use, and assist the patient in wearing them during waking hours

- Provide adequate room lighting

- Minimize glare (e.g., offer sunglasses, draw window covering, position with face away from window)

- Provide educational materials in large print as available

- Read pertinent information to the patient

- Provide magnifying devices

- Report any changes to the nurse

Impaired Speech[17]

Some patients may have problems processing what they are hearing or in responding to questions due to dementia, brain injuries, or prior strokes. This difficulty is referred to as aphasia. There are different types of aphasia. People with expressive aphasia understand speech and know what they want to say, but frequently speak in short phrases that are produced with great effort. For example, they may intend to say, “I would like to go to the bathroom,” but instead the words, “Bathroom, Go,” are expressed. People with receptive aphasia often speak in long sentences, but what they say may not make sense. They are unable to understand both verbal and written language. Aphasia often causes the person to become frustrated when they cannot communicate their needs. Review the following evidence-based strategies to enhance communication with a person with impaired speech[18]:

- Modify the environment to minimize excess noise and decrease emotional distress

- Phrase questions so the patient can answer using a simple “Yes” or “No,” being aware that patients with expressive aphasia may provide automatic responses that are incorrect

- Monitor the patient for frustration, anger, depression, or other responses to impaired speech capabilities

- Provide alternative methods of speech communication (e.g., writing tablet, flash cards, eye blinking, communication board with pictures and letters, hand signals or gestures, or computer)

- Adjust your communication style to meet the needs of the patient (e.g., stand in front of the patient while speaking, listen attentively, present one idea or thought at a time, speak slowly but avoid shouting, use written communication, or solicit the family’s assistance in understanding the patient’s speech)

- Ensure the call light is within reach

- Repeat what the client said to ensure accuracy

- Instruct the client to speak slowly

- Read the care plan for instructions from the speech therapist

- Report any changes to the nurse

Responding to Challenging Situations

Being a care provider is a very rewarding career, but it also includes dealing with challenging situations. Using strong communication techniques can de-escalate situations and put patients, loved ones, and staff at ease. It is impossible to predict what behavior you may encounter as a health care worker, but having a solid basis of communication techniques can prepare you to better handle unique situations.

Memory Impairment and Behavioral Health Issues

As a nursing assistant, you will likely encounter older adults with varying degrees of memory impairment. Older adults are defined as adults aged 65 years old or older.[19] Residents with memory issues often become confused and can feel overwhelmed by everyday situations. For those with impaired cognitive functioning like dementia, it may not be possible to reorient them to the current time and place or to move them on from thoughts that are not based in the current situation. Aphasia and confusion can cause frustration that can result in agitation or aggression. Agitation refers to behaviors that fall along a continuum ranging from verbal threats and motor restlessness to harmful aggressive and destructive behaviors. Mild agitation includes symptoms such as irritability, oppositional behavior, inappropriate language, and pacing. Severely agitated patients are at immediate risk of harming themselves or others through assaultive or self-injurious behavior, and they are capable of causing property damage.[20] Aggression is an act of attacking without provocation.[21] Agitation and aggression will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 10, but general guidelines to prevent aggression and agitation include the following:

- Keep the environment calm and as quiet as possible.

- Build trusting relationships by learning resident preferences and routines.

- Gather information from family members and loved ones about the patient’s background and beliefs.

- Offer choices to allow the patient to communicate preferences, but do not cause them to be overwhelmed with too many decisions.

- Stick to a daily routine for ADLs, meals, and activities.

- Empathize with the resident and understand that challenging behavior is often communication of emotion due to cognitive impairment and not a choice.

- Practice validation therapy. Validation therapy is a method of therapeutic communication used to connect with someone who has moderate- to late-stage dementia and avoid agitation. It places more emphasis on the emotional aspect of a conversation and less on the factual content, thereby imparting respect to the person, their feelings, and their beliefs. Validation may require you to agree with a statement that has been made, even though the statement is neither true or real, because to the person with dementia, it feels both true and real.[22] For example, if the resident with dementia believes they are waiting to catch the bus and is intent on doing so, sit with them by the window as if you are waiting for a bus and continue to have interaction with them until they are no longer concerned with the bus.

- Redirect behavior if appropriate. For example, suggest alternative activities such as walking around the facility, looking at photos, listening to music, or other activities the resident enjoys.

- Focus on safety for residents experiencing delusions or hallucinations. Delusions are unshakable beliefs in something that isn’t true or based on reality. For example, a resident may refuse to eat breakfast because they have a delusion that staff are trying to poison them. Hallucinations are sensing things such as visions, sounds, or smells that seem real but are not. For example, a resident may refuse to enter a room because they have hallucinations of big spiders crawling on the walls. If a patient is having delusions or hallucinations, never contradict them or tell them what they perceive isn’t real. Instead, empathize with them and do whatever is possible to help them feel safe. For example, offer to move to another area or investigate what the resident is concerned about.

Dealing With Stress

The stress response is a common psychological barrier to effective communication. It can affect the message sent by the sender or the reception by the receiver. The stress response is a common reaction to life events, such as a health care worker feeling overwhelmed with tasks to complete for multiple patients or a patient feeling stressed when admitted to a hospital or receiving a new diagnosis. Symptoms of the stress response include irritability, sweaty palms, a racing heart, difficulty concentrating, and impaired sleep. It is important to recognize symptoms of the stress response in ourselves and our patients and use strategies to manage the stress response when communicating.

There are several stress management strategies to use to manage the stress response[23]:

- Use relaxation breathing to become aware of one’s breathing. This technique includes taking deep breaths in through the nose and blowing it out through the mouth. This process is repeated at least three times in succession and then as often as needed throughout the day.

- Make healthy diet choices. Avoid caffeine, nicotine, and junk food because these items can increase feelings of anxiety or being on edge.

- Make time for exercise. Exercise stimulates the release of natural endorphins that reduce the body’s stress response and also helps to improve sleep.

- Get enough sleep. Set aside at least 30 minutes before going to bed to wind down from the busyness of the day. Avoid using electronic devices like cell phones before bedtime because the backlight can affect sleep.

- Use progressive relaxation. There are several types of progressive relaxation techniques that focus on reducing muscle tension and using mental imagery to induce calmness. Progressive relaxation generally includes the following steps:

- Start by lying down somewhere comfortable and firm, like a rug or mat on the floor. Get yourself comfortable.

- Relax and try to let your mind go blank. Breathe slowly, deeply, and comfortably, while gradually and consciously relaxing all your muscles, one by one.

- Work around the body one main muscle area at a time, breathing deeply, calmly, and evenly. For each muscle group, clench the muscles tightly and hold for a few seconds, and then relax them completely. Repeat the process, noticing how it feels. Do this for each of your feet, calves, thighs, buttocks, stomach, arms, hands, shoulders, and face.

Managing Clients’ and Family Members’ Stress

Being cared for by strangers can feel very challenging to clients. Residents in long-term care settings have frequently experienced major physical and/or cognitive changes that caused a loss of their independence and sometimes some of their autonomy. Autonomy is each individual’s right to self-determination and decision-making based on their unique values, beliefs, and preferences. It is important for the nursing assistant to empathize with these losses and the new reality that residents must become accustomed to when moving into a long-term care facility. Reflect on the exercise in the following box to understand a resident’s feelings during their transition:

Reflection Activity

When you wake up in the morning, imagine that you cannot get out of bed on your own. Think about putting on your call light as you need to use the restroom and having to wait until someone is available to help. As you look around the room, you see some of your belongings, but many are no longer there. The floor is clean but bare; your recliner is nearby but you can’t move into it. You wish you could go to the kitchen to have coffee with your partner, but they are no longer around. You miss your pet that used to sleep with you each night. Finally, an aide arrives, and although they are friendly, it is another new face that will help you to the bathroom and with other care needs.

Clients usually become more comfortable with their new reality as they become familiar with a new routine and their new home. It is important to remember that emotions related to loneliness, feeling like a burden, and loss of independence can arise at any time. The nursing assistant can help residents adjust to their new environment in the following ways:

- Greet clients by their preferred name and introduce yourself.

- Ask clients their preferences for their care. Always communicate what you will be doing next and allow the resident to redirect or refuse care.

- Provide privacy when assisting with cares.

- Use confidentiality when documenting information or reporting to other members of the health care team.

- Treat belongings carefully and with respect and remember the client’s room is their home.

- Listen to the resident and address concerns if they arise. If you cannot adequately address the resident’s concerns, communicate these concerns to the nurse or supervisor.

Family members and other loved ones may have questions and concerns about the resident’s care. Read more information about managing their concerns in the following “Dealing With Conflict” section.

Dealing With Conflict

Health care professionals provide personal care at integral times in the lives of patients. The demands of caregiving and the associated rapid decision-making process can create stress for health care team members, patients, family members, and other loved ones. Managing care and making decisions can cause conflict among all involved. As a nursing assistant, it is important to be aware of your role and responsibility when managing conflict.

When a patient does not want to participate in care necessary to support their proper hygiene or health maintenance, the nursing assistant can use effective communication to encourage actions and promote desired outcomes. When a resident declines care, here are some actions the nursing assistant may use that respect their choices but allow care standards to be met:

- Re-approach the resident at a later time.

- Offer an alternative method. For example, a resident may not want to shower or take a bath but would be willing to have a full bed bath, allowing them to stay covered and warm throughout care.

- Remind the resident what may occur if care is not provided, such as higher risk of infection, open areas in the skin, odor, etc.

- Encourage as much control and independence as possible. Allow the resident to direct the process if able and offer as many choices as are appropriate.

Family members and other supports may have concerns about the plan of care for a resident. This may be due to lack of medical knowledge, little experience with the procedures of health care facilities, or a feeling of helplessness in regard to their loved one’s situation. The nursing assistant should listen to and acknowledge these concerns. Following confidentiality guidelines, interventions included in the plan of care can be discussed if the resident has permitted disclosure of this information. However, the nursing assistant should only disclose information when they have confirmed the resident has permitted disclosure. It may be beneficial for family members or others involved to discuss concerns with the nurse or unit supervisor and possibly schedule a care conference with the health care team to resolve their concerns. In this instance, the aide should understand that any anger directed at them may be a result of the situation rather than a reflection of anything they have personally done.

Conflicts among coworkers can also be addressed with assertive communication techniques. As discussed in the “Communication Styles” subsection, using assertive communication is the best approach to address workplace conflict and a respectful way to make one’s viewpoints known. Communication should start between the two parties that have the conflict before involving other staff. It is best to think about the situation and develop a potential solution before approaching the coworker. Frame the situation from your perspective using “I” messages. If the situation is especially tense, it may be beneficial to allow some time between the experience and the discussion to reduce stress and think more logically about the conflict. A typical time frame is to wait one day to think logically about a conflict before addressing it, often referred to as the “24-hour Rule.” If you have discussed your concerns with the coworker and offered a potential solution without any resolution in the situation, it is appropriate to notify your supervisor for additional assistance at that time. See an example of conflict resolution in the following box.

Example of Conflict Resolution

A nursing assistant becomes frustrated with a coworker who works on the previous shift when they continue to neglect to empty the wastebaskets and tidy up the residents’ rooms before the end of their shift. When it became apparent this was a pattern of behavior and not an isolated incident due to an exceedingly busy shift, the nursing assistant approached the coworker and said, “I feel frustrated when I start my shift with full wastebaskets and untidy rooms for the residents you care for. Can you help me understand why these things aren’t accomplished by the end of your shift? It works for me to clean up the room when I am finished assisting the resident. That way I don’t forget to come back, and the residents seem to appreciate it as well.” The coworker apologized for this oversight and committed to completing these tasks before leaving at the end of their shift.

References

- 1.

- Abdolrahimi, M., Ghiyasvandian, S., Zakerimoghadam, M., & Ebadi, A. (2017). Therapeutic communication in nursing students: A Walker & Avant concept analysis. Electronic Physician , 9(8), 4968–4977. ↵ 10.19082/4968 . [PMC free article: PMC5614280] [PubMed: 28979730] [CrossRef]

- 2.

- Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies , 4(2), e29475. https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/ ↵ . [PMC free article: PMC4557413] [PubMed: 26339672] - 3.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 4.

- Abdolrahimi, M., Ghiyasvandian, S., Zakerimoghadam, M., & Ebadi, A. (2017). Therapeutic communication in nursing students: A Walker & Avant concept analysis. Electronic Physician , 9(8), 4968–4977. ↵ 10.19082/4968 . [PMC free article: PMC5614280] [PubMed: 28979730] [CrossRef]

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- “Flickr_-_Official_U

.S ._Navy_Imagery_-_A_nurse _examines_a_newborn_baby..jpg” by Official Navy Page from United States of America MC2 John O'Neill Herrera/U.S. Navy is licensed in the Public Domain ↵. - 8.

- American Nurse. (n.d.). 17 therapeutic communication techniques. https://www

.myamericannurse .com/therapeutic-communication-techniques/ ↵. - 9.

- Balchan, M. (2016, February 16). The magic of genuine communication. http:

//michaelbalchan.com/communication/ ↵. - 10.

- Morrison, E. (2019). Empathetic communication in healthcare. EM Consulting. https://work

.cibhs.org /sites/main/files/file-attachments /empathic _communication_in _healthcare_workbook.pdf?1594162691 ↵. - 11.

- Burke, A. (2021). Therapeutic communication: NCLEX-RN. RegisteredNursing.org. https:

//www .registerednursing.org /nclex/therapeutic-communication/ ↵. - 12.

- Burke, A. (2021). Therapeutic communication: NCLEX-RN. RegisteredNursing.org. https:

//www .registerednursing.org /nclex/therapeutic-communication/ ↵. - 13.

- Smith, L. L. (2018, June 12). Strategies for effective patient communication. American Nurse. https://www

.myamericannurse .com/strategies-for-effective-patient-communication/ ↵. - 14.

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵.

- 15.

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵.

- 16.

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵.

- 17.

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵.

- 18.

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵.

- 19.

- HealthyPeople.gov. (n.d.). Older adults. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://www

.healthypeople .gov/2020/topics-objectives /topic/older-adults ↵. - 20.

- ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Agitation. https://www

.sciencedirect .com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/agitation ↵. - 21.

- 22.

- Hoyt, J. (Ed.). (2020, January 27). Validation therapy in dementia care. SeniorLiving.org. https://www

.seniorliving .org/health/validation-therapy/ ↵. - 23.

- American Psychological Association. (2019, November 1). Healthy ways to handle life's stressors. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/tips ↵.

1.4. HUMAN NEEDS AND DEVELOPMENTAL STAGES

It is important to understand human needs and developmental stages to communicate effectively and provide holistic care.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs was created in 1943 by American psychologist Abraham Maslow. Maslow’s theory is based on the ranking of the importance of human needs and the belief that human actions are based on motivation to meet these needs. See an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in Figure 1.5.[1]

Figure 1.5

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s theory states that unless the basic needs in the lower levels of the hierarchy are met, humans cannot experience the higher levels of psychological and self-fulfillment needs. The levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs have the following definitions[2]:

- 1.

Physiological needs: This is the most important level with basic needs humans must have to stay alive and function, including air, food, drink, shelter, clothing, warmth, sex, and sleep.

- 2.

Safety needs: People want to experience order, predictability, and control in their lives. This includes emotional security, freedom from fear, and health and well-being (such as safety against falls and injury). For new residents in a long-term care facility, this level includes becoming comfortable in familiar surroundings as opposed to feeling apprehension when experiencing a new environment.

- 3.

Love and belongingness: After physiological and safety needs have been fulfilled, the third level of human needs is social and involves feelings of belongingness. Belongingness refers to a human emotional need for interpersonal relationships, connectedness, and being part of a group. A group may mean biological families, friends, or other supporters. It may also include physical intimacy and romantic relationships.

- 4.

Esteem needs: Esteem needs include self-worth and feelings of accomplishment and respect. It includes how one views oneself and the feeling of contributing to something of importance.

- 5.

Self-actualization: Self-actualization is the highest level and refers to the realization of a person’s potential and self-fulfillment. This level refers to the desire to attain life goals and being truly satisfied in being the most one can be.

Maslow theorized that one cannot attain a higher level in any of these categories if the levels below are not met. For example, one is not motivated by a sense of belonging if they are focused on obtaining basic needs such as food, water, and shelter. The hierarchy is subjective because each individual determines what each level means for them. For instance, for one person, safety may mean living in the neighborhood where they grew up, whereas for another individual it means having a daily routine. Belongingness to one person may mean being a part of a community group whereas to another it may mean having one very close friend. Self-esteem and feelings of accomplishment may be defined by one person as successfully graduating from high school, whereas to another it is defined by being able to run a mile without stopping. Self-actualization is defined by each individual and can mean things such as being a good parent, graduating from college, or achieving one’s dream of becoming a nurse.

The levels of belongingness and self-actualization also include a person’s spirituality and how they find meaning and purpose in life. Spirituality is often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept that includes how people seek meaning and purpose in life, as well as establish relationships with family, their community, nature, and/or a higher power.[3]

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a good basis for providing holistic care and communicating with clients based on their needs and preferences. For example, in nursing, priorities of care are based on physiological needs and safety. Additionally, knowing that a newly admitted resident may have difficulty reaching a higher level of needs if their basic needs are not met is a good starting point for providing care.

Strategies that integrate Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs when providing care to residents include the following:

- Following the nursing plan of care to meet physiological needs.

- Implementing fall precautions to keep residents safe.

- Answering call lights promptly and consistently providing a calm, comfortable environment to make residents feel secure.

- Respecting residents’ belongings and asking their preferences for grooming, bathing, and meals to satisfy self-esteem needs.

- Encouraging interaction among residents with similar interests to promote a feeling of belongingness.

- Offering to bring residents to on-site religious activities or referring them to social services for a chaplain visit to promote self-actualization and a feeling of belongingness.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs can also be applied to the work environment to enhance professionalism by doing the following:

- Offering assistance to coworkers when able to promote a feeling of security and belongingness and also maintaining residents’ physiological needs and safety as a team.

- Participating fully in the reporting and documentation process of the facility to meet residents’ physiological and safety needs.

- Accurately following training and agency policies and procedures to encourage feelings of self-esteem in the health care worker.

- Being accountable for one’s actions and job responsibilities to promote a feeling of self-actualization by meeting one’s potential.

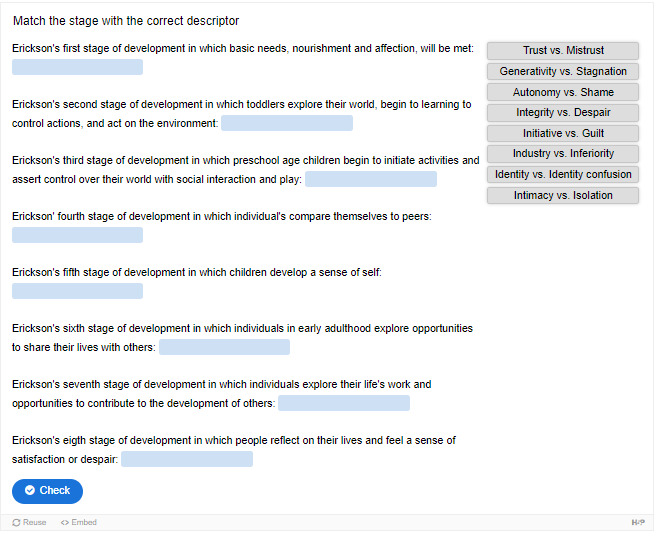

Erikson’s Stages of Development

Another psychologist named Erik Erikson created a theory of psychosocial development that also describes how one’s personality is developed. It theorizes there are eight stages of development based on a person’s chronological age. Development occurs based on the main conflict or challenge confronted during that period of time. Each stage can create either a virtue/strength or a maladaptive tendency. Erikson proposed that those who have a stronger sense of identity from resolving these conflicts over time have fewer conflicts within themselves and with others and, subsequently, a decreased level of anxiety.[4]

Erikson’s stages of development are defined as trust versus mistrust, autonomy versus shame, initiative versus guilt, industry versus inferiority, identity versus identity confusion, intimacy versus isolation, generativity versus stagnation, and integrity versus despair[5]:

Trust vs. Mistrust

The first stage establishes trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met. Trust is the basis of our development during infancy (birth to 12 months). Infants are dependent on their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable.[6]

Autonomy vs. Shame

Toddlers begin to explore their world and learn that they can control their actions and act on the environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy versus shame and doubt by working to establish independence. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a two-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions has an effect on her sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on her environment, she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.[7]

Initiative vs. Guilt

Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Those who do will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage may develop feelings of guilt.[8]

Industry vs. Inferiority

During the elementary school stage (ages 7–11), children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate when they don’t measure up.[9]

Identity vs. Identity Confusion

In adolescence (ages 12–18), children develop a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. Teens who do not make a conscious search for identity or those who are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future may have a weak sense of self and experience role confusion as they are unsure of their identity and confused about the future.[10]

Intimacy vs. Isolation

People in early adulthood (i.e., 20s through early 40s) are ready to share their lives with others after they have developed a sense of self. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.[11]

Generativity vs. Stagnation

When people reach their 40s, they enter a time period known as middle adulthood that extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity versus stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others, through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation, having little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.[12]

Integrity vs. Despair

The mid-60s to the end of life is a period of development known as late adulthood. People in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity and often look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” or “could have” been. They face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.[13]

By combining Maslow’s and Erickson’s theories of development and motivation, we can begin to understand why some patients need more encouragement, space, or time to allow caregivers to provide assistance with their ADLs to maintain physical and emotional health.

View the following YouTube video[14] for more information about Erikson’s theory of development: Erikson’s Psychosocial Development | Individuals and Society.

Assisting With Spiritual Needs

When clients experience a serious illness or injury, they often grapple with the existential question, “Why is this happening to me?” This question can be a sign of spiritual distress defined as, “A state of suffering related to the inability to experience meaning in life through connections with self, others, the world, or a superior being.” Spiritual well-being is a pattern of experiencing meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, and/or a power greater than oneself. Spirituality is often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept. Elements of spirituality include faith, meaning, love, belonging, forgiveness, and connectedness.[15] Spirituality and religion can change over a person’s lifetime and vary greatly between people. Some people who are very spiritual may not belong to a specific religion.

Religion is frequently defined as an institutionalized set of beliefs and practices. Many religions have specific rules about food, religious rituals, clothing, and touching. Supporting these rules when they are meaningful part of a resident’s spirituality is an effective way to support the resident and maintain a caring, professional relationship. The nursing assistant should discuss these aspects with the nurse to assure they support the plan of care for the resident and encourage other staff members to provide support. Many nursing homes and assisted living facilities offer religious or spiritual opportunities through their Activities departments.

Many hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and hospices employ professionally trained chaplains to assist with the spiritual, religious, and emotional needs of clients, family members, and staff. In these settings, chaplains support and encourage people of all religious faiths and cultures and customize their approach to each individual’s background, age, and medical condition. Chaplains can meet with any individual regardless of their belief, or lack of belief, in a higher power and can be very helpful in reducing anxiety and distress.[16] NAs may suggest chaplain services for their clients.

An important way to assist a client with their spiritual well-being is to ask them what they need to feel supported in their faith and then try to accommodate their requests, if possible. Explain that spiritual health helps the healing process. For example, perhaps they would like to speak to their clergy, spend some quiet time in meditation or prayer without interruption, or go to the on-site chapel. Many agencies have chaplains onsite that can be offered to patients as a spiritual resource.[17]

If the client or family member requests a nursing assistant to pray with them, it is acceptable to pray with them or find someone who will. Some nursing assistants may feel reluctant to pray with patients when they are asked for various reasons; they may feel underprepared, uncomfortable, or unsure if they are “allowed to.” Nursing assistants, nurses, and other health care team members are encouraged to pray with their patients to support their spiritual health, as long as the focus is on the patient’s preferences and beliefs, not their own preferences. Having a short, simple prayer ready that is appropriate for any faith may help a health care professional feel prepared for this situation. However, if the nursing assistant does not feel comfortable praying with the patient as requested, the nurse should be notified so the chaplain can be requested to participate in prayer with the patient.[18]

It is important to support clients within their own faith tradition, but it is not appropriate for the nursing assistant to take this opportunity to attempt to persuade a patient towards a preferred religion or belief system. The role of the nursing assistant is to respect and support the client’s values and beliefs, not promote the nursing assistant’s values and beliefs.[19]

References

- 1.

- 2.

- McLeod, S. (2020, March 20). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. https://www

.simplypsychology .org/maslow.html ↵. - 3.

- Puchalski, C. M., Vitillo, R., Hull, S. K., & Reller, N. (2014). Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine , 17(6), 642–656. ↵ 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427 . [PMC free article: PMC4038982] [PubMed: 24842136] [CrossRef]

- 4.

- 5.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 6.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 7.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 8.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 9.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 10.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 11.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 12.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 13.

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/psychology-2e /pages/1-introduction ↵. - 14.

- Desai, S. (2014, February 25). Erikson’s psychosocial development | Individuals and society | MCAT | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. https://youtu

.be/SIoKwUcmivk ↵. - 15.

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York, pp. 365, 372-377. ↵.

- 16.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 17.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 18.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

- 19.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵.

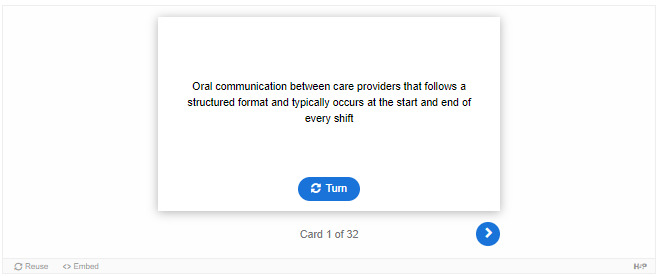

1.5. DOCUMENTING AND REPORTING

Guidelines for Documentation

Accurate documentation and reporting are vital to proper client care. Reporting is oral communication between care providers that follows a structured format and typically occurs at the start and end of every shift or whenever there is a significant change in the resident. Documentation is a legal record of patient care completed in a paper chart or electronic health record (EHR). It is also referred to as charting. Checklists and flowcharts completed in the resident’s room may also become part of the paper chart. Documentation is used in a court of law to prove patient care was completed if a lawsuit is filed, with the rule of thumb being, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Documentation is also reviewed by other health care team members to provide holistic care.

Accurate documentation should follow these guidelines:

- The client’s chart is confidential and should only be shared with those directly involved in care. If using paper, cover information with a blank sheet. When using technology, be sure screens are visible only to you and log out after each use. Never share security measures like passwords or PIN with anyone else.

- Document as soon as any care is completed.

- Include date, time, and signature per facility policy.

- Use facts, not opinions. An opinion is, “The resident doesn’t like their food.” Instead, a fact should be charted, such as, “The resident refused their meal and stated they were not hungry.”

- Use measuring tools, such as a graduated cylinder or a tape measure, whenever possible to provide accurate data. If you do have to estimate, provide a comparison such as, “Drainage noted on the bandage was the size of a quarter.”

- If you chart on paper, always use a black pen. If you make a mistake, draw only one line through the entry, write the word “mistaken entry,” and add your initials. Do not use correction fluid or completely black out the entry.

Long-term care facilities are required to complete additional documentation called a Minimum Data Set (MDS). The MDS is a standardized assessment tool for all residents of long-term care facilities certified to receive reimbursement by Medicare or Medicaid. The MDS is completed by a registered nurse who reviews documentation by nursing assistants to complete some parts of the MDS. Accurate documentation is vital so that facilities are appropriately reimbursed for the services provided to clients.