Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-.

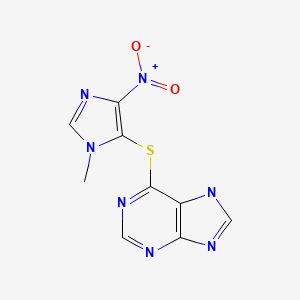

CASRN: 446-86-6

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

North American and European expert guidelines, the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry and other experts consider azathioprine to be acceptable to use during breastfeeding.[1-13] Studies in women with inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus or transplantation taking doses of azathioprine up to 200 mg daily for immunosuppression have found either low or unmeasurable levels of the active metabolites in milk and infant serum. Some evidence indicates a lack of adverse effects on the health and development of infants exposed to azathioprine during breastfeeding up to 4.6 years of age, but long-term follow-up for effects such as carcinogenesis have not been performed. Mothers with decreased activity of the enzyme that detoxifies azathioprine metabolites may transmit higher levels of drug to their infants in breastmilk. Poorly documented cases of mild, asymptomatic neutropenia and increased rates of infection have been reported occasionally. It might be desirable to monitor exclusively breastfed infants with a complete blood count with differential, and liver function tests if azathioprine is used during lactation, although some authors feel that monitoring is unnecessary.[14] Avoiding breastfeeding for 4 hours after a dose should markedly decrease the dose received by the infant in breastmilk.[15]

Drug Levels

Azathioprine is rapidly metabolized to the active metabolite mercaptopurine which is further metabolized to active metabolites including 6-methylmercaptopurine, thioguanine, 6-thioguanine nucleosides (6-TGNs), 6-methylmercaptopurine, and 6-methylmercaptopurine nucleosides (6-MMPNs). The enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) is responsible for metabolism of 6-TGNs. Deficiencies in this enzyme can lead to excessive toxicity.

Maternal Levels. Mercaptopurine milk levels were measured in 2 patients receiving azathioprine following renal transplantation. In one mother who was 2 days postpartum, peak colostrum levels occurred 2 and 8 hours after a 75 mg oral dose and were 3.4 and 4.5 mcg/L, respectively. In the other mother who was 7 days postpartum, a peak mercaptopurine milk level of 18 mcg/L occurred 2 hours after a 25 mg oral dose.[16] The milk levels of these 2 mothers correspond to 0.05% and 0.6% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosages, respectively. Infant serum levels were not measured.

Four women receiving an immunomodulator to treat inflammatory bowel disease had metabolite levels measured in milk during the first 6 weeks postpartum. The abstract does not mention the specific drug and dose being taken, but the azathioprine metabolites 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) and 6-TGNs were measured. Although therapeutic levels were found in maternal serum, 6-MMP (<650 mcg/L) and 6-TGNs were undetectable (<123 mcg/L) in milk (time of collection not stated).[17]

A case series described 2 mothers who took azathioprine 100 mg daily while breastfeeding. Each mother collected milk samples over a 24-hour period, 5 and 6 samples, respectively. Mercaptopurine was undetectable (<5 mcg/L) in all samples. The authors estimated that the maximum dose of mercaptopurine that a completely breastfed infant would receive would be 0.09% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage or 0.07% of the dose given to infants following cardiac transplantation.[18]

Ten women who were taking azathioprine 75 to 150 mg daily at the time of delivery for systemic lupus erythematosus (n = 7), renal transplant (n = 2) or Crohn’s disease (n = 1) donated milk samples on days 3 to 4, 7 to 10 and 28 postpartum. Milk was collected before the single daily dose and at each breastfeed for 12 to 18 hours for a total of 31 samples. Only one woman taking azathioprine 100 mg daily had mercaptopurine detected in her milk. On day 28 postpartum, milk mercaptopurine concentrations were 1.2 mcg/L at 3 hours and 7.6 mcg/L at 6 hours after the dose.[19]

Eight lactating women who were 1.5 to 7 months postpartum were taking azathioprine in dosages ranging from 75 to 200 mg daily for inflammatory bowel disease. All of the women had wild type TPMT phenotypes. Peak mercaptopurine milk concentrations occurred within the first 4 hours after ingesting of the dose of azathioprine and ranged from 2 to 50 mcg/L. By 5 hours after the dose, the milk concentrations of mercaptopurine had dropped markedly in all patients. The authors estimated that the “worst case” infant intake of mercaptopurine would 0.0075 mg/kg daily which is less than 1% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.[20]

Infant Levels. Four infants were breastfed (3 exclusively, 1 rarely received formula) during maternal use of azathioprine orally in dosages of 1.2 to 2.1 mg/kg daily. All of the mothers and infants had the wild type TPMT *1/*1 genotype and all of the mothers had normal enzyme activity. At 3 to 3.5 months of age, all of the infants had undetectable blood levels of 6-TGNs and 6-MMPN.[21] The authors later updated this report to include 2 previously unreported mother-infant pairs. These infants also had undetectable blood levels of 6-TGNs and 6-MMPN.

Seven infants were breastfed during maternal intake of azathioprine in single oral doses of 75 to 150 mg daily. None had detectable mercaptopurine or thioguanine in their blood obtained between days 1 and 28 postpartum.[19]

Three infants whose mothers were taking azathioprine for inflammatory bowel disease (n = 2) or systemic lupus erythematosus (n = 1) were breastfed during maternal use of azathioprine. Azathioprine doses were 100 mg (plus prednisolone), 150 mg (plus infliximab) and 175 mg daily. In 1 infant, thioguanine was low, but detectable in blood at 3 days of age and 6-MMPN was undetectable; at 3 weeks of age, neither metabolite was detectable. In another infant, neither metabolite was detectable at 3 weeks of age. Neither assay limits nor specific maternal doses were stated in the published abstract.[22]

A woman began taking azathioprine 100 mg (1.4 mg/kg) daily for Crohn’s disease while breastfeeding (extent not stated) her 3-month-old infant. After 8 days and 3 months of maternal therapy, 6-TGNs were measured, although breastfeeding had been tapered to zero by 3 months. On both occasions, 6-TGNs were not detectable in the blood of the infant. The assay limit was not stated.[23]

Effects in Breastfed Infants

Three infants were breastfed during long-term maternal azathioprine 75 to 100 mg daily and methylprednisolone use following renal transplantation. All three infants had no abnormal blood counts, no increased frequency of infections and above average growth rates.[16,24]The IgA levels in one mother’s breastmilk were measured and found to be normal.[16]

One infant was breastfed for 6 days after birth by a mother who was taking azathioprine 75 mg daily in addition to cyclosporine. Nursing was interrupted for 4 days, then partial breastfeeding was reestablished. The infant showed no signs of renal or neurologic toxicity or hirsutism during long-term follow up.[25]

Twelve infants were breastfed for up to 12 months during maternal use of azathioprine 50 to 100 mg daily (6 with concomitant cyclosporine) following kidney or kidney-pancreas transplantation. Kidney function was normal in all infants when measured after breastfeeding had ceased. The growth and psychomotor development of all infants was normal.[26]

One infant was exclusively breastfed for 10.5 months during maternal use of azathioprine 100 mg daily, cyclosporine and prednisone. Partial breastfeeding continued for 2 years. The infant thrived with normal growth at 12 months. The mother also breastfed a second child while on the same drug regimen.[27]

Four infants were breastfed (3 exclusively, 1 rarely received formula) during maternal use of azathioprine orally in dosages of 1.2 to 2.1 mg/kg daily. At 3 to 3.5 months of age, all infants were healthy and were within the 50th to 95th percentiles on growth charts.[17] The authors reported 2 additional infants who received azathioprine via breastmilk with no adverse reactions detected.[28]

In another case series, 4 infants were breastfed (partially in 1 case, not stated in the others) during maternal use of azathioprine. Two mothers took 100 mg daily, 1 took 75 mg daily and 1 took 50 mg daily and partially breastfed her preterm infant. All were taking several other medications concurrently. One infant was followed up at 1 month, 2 at 2 months and 1 at 1 year of age. No adverse events were reported in any of the infants and all were growing and developing normally.[18]

Six infants whose mothers were breastfeeding and taking azathioprine were monitored monthly for the duration of their breastfeeding with blood counts and for evidence of infection. One infant developed a low blood count and breastfeeding was discontinued; the other 5 infants continued to breastfeed apparently without harm. The dosages of azathioprine, concurrent medications and the extent of breastfeeding were not reported in the brief published abstract.[29]

Ten infants, 3 preterm, were breastfed during maternal intake of azathioprine in single oral doses of 75 to 150 mg daily. No signs of immunosuppression were seen in the infants during the first 28 days postpartum. In 7 of the infants, white cell and neutrophil counts were performed between days 1 and 28 postpartum. One infant had a borderline low neutrophil count but a normal white cell count.[19]

A survey of women with autoimmune hepatitis found that 8 infants of 4 women had been breastfed (extent not stated) during maternal azathioprine use in unspecified dosages. No adverse effects were reported by the mothers.[30]

An infant was breastfed (extent not stated) from birth to the age of 3 months during maternal therapy with azathioprine 100 mg (1.4 mg/kg) daily. During the 6 months of follow-up, the infant thrived and had no infections.[23]

A nonrandomized, prospective study in Austria followed the infants of 23 women with inflammatory bowel disease who were treated in one clinic. Mothers who received azathioprine (median dose 150 mg daily; range 100 to 250 mg daily) for treatment breastfed for a median of 6 months (range 1 to 18 months) and those who did not take azathioprine breastfed for a median of 8 months (range 3.5 to 23 months). Follow-up occurred at a median of 3.3 years in the azathioprine-exposed infants (n = 15) and 4.7 years in the unexposed infants (n = 15). No differences were found in mental or physical development between the two groups of infants. More infants who were unexposed to azathioprine had more than 2 colds annually and more conjunctivitis episodes than in the unexposed group. No difference was seen in the numbers of other infections between the groups.[31]

In The Netherlands, 30 infants of mothers taking either azathioprine (n = 28) or mercaptopurine (n = 2) for inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and postpartum were followed at 1 to 6 years of age using a 43-item quality of life questionnaire. Of this cohort, 9 infants were breastfed for a mean of 7 months (range 3 to 13 months) No statistically significant differences were found between breastfed and formula-fed infants in any of the 12 domains of the survey.[32]

In France, 30 infants of 29 mothers who took azathioprine 50 to 175 mg daily during pregnancy and nursed for at least 1 month (range 1 to 17 months) were followed. Three infants had low white blood cell (WBC) counts at birth that normalized during breastfeeding (extent not stated). Of 20 infants who had later WBC counts, one had mild, asymptomatic neutropenia during 1.5 months of breastfeeding that persisted for 15 days following breastfeeding discontinuation. No other adverse effects were seen during a median of 9.5 months (range 1.5 to 30 months) of follow-up.[33]

In a multi-center study of women with inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy (the PIANO registry), 102 women received a thiopurine (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) and another 67 received a thiopurine plus a biological agent (adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, infliximab, natalizumab, or ustekinumab) while breastfeeding their infants. Among those who received a thiopurine or combination therapy while breastfeeding, infant growth, development or infection rate was no different from 208 breastfed infants whose mothers received no treatment.[34]

As of December 2013, The National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry has collected information on a total of 83 mothers who had breastfed 117 infants for as long as 42 months while taking azathioprine with no apparent adverse effects in infants.[2]

A national survey of gastroenterologists in Australia identified 21 infants who were breastfed by mothers taking a combination of allopurinol and a thiopurine (e.g., azathioprine, mercaptopurine) to treat inflammatory bowel disease. All had taken the combination during pregnancy also. Two postpartum infant deaths occurred, both at 3 months of age. One was a twin (premature birth-related) and the other from SIDS. The authors did not believe the deaths were medication related.[35] No information was provided on the extent of breastfeeding, specific thiopurines, drug dosages or the outcomes of the other infants.

A mother with a liver transplant was maintained on belatacept 10 mg/kg monthly, slow-release tacrolimus (Envarsus and Veloxis) 2 mg daily, azathioprine 25 mg daily, and prednisone 2.5 mg daily. She breastfed her infant for a year (extent not stated). The infant’s growth and cognitive milestones were normal.[36]

An Australian case series reported 3 women with heart transplants who had a total of 5 infants, all of whom were breastfed (extent not stated). Two of the women took azathioprine 75 mg once daily postpartum. No adverse infant effects were reported up to the times of discharge.[37]

An infant was born at 38 weeks to a mother who was taking azathioprine, mesalamine and sulfasalazine during pregnancy for severe ulcerative colitis. On routine postnatal screening (time postpartum not specified), the infant was found to have a low B-cell kappa deleting recombination excision circles (KREC) of 15 copies/microliter. Breastfeeding was discontinued and 2 weeks later, the infant’s KREC level improved to a normal level of 355 copies/microliter, with normal CD19+ B-cell counts. It is unclear if the abnormality was caused by transplacental passage or breastmilk exposure to azathioprine or some other cause.[38]

In a cohort study, over a 10-year period 17 nursing mothers with a rheumatic disease took azathioprine during partial or exclusive breastfeeding. No mention was made of adverse effects in their infants.[39]

A retrospective study was performed on data from patients with lupus erythematosus from 10 hospitals in the United Kingdom who received or did not receive azathioprine during pregnancy and lactation. Fifty-nine infants whose mothers took azathioprine during pregnancy and/or breastfeeding and were compared to 140 infants who were not exposed. Infants were followed for a median of 4.55 years. There were statistically significantly more infections reported in infants exposed to azathioprine (24.1%) compared to non-exposed infants (13.7%). The percentage of infants who were breastfed was not stated.[40]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

Cases of hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea with normal prolactin have been reported rarely.[41,42]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

(Immunosuppression) Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus; (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) Budesonide, Infliximab, Mesalamine, Prednisone; (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus) Hydroxychloroquine, Prednisone

References

- 1.

- Nielsen OH, Maxwell C, Hendel J. IBD medications during pregnancy and lactation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:116-27. [PubMed: 23897285]

- 2.

- Constantinescu S, Pai A, Coscia LA, et al. Breast-feeding after transplantation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014;28:1163-73. [PubMed: 25271063]

- 3.

- Nguyen GC, Seow CH, Maxwell C, et al. The Toronto Consensus Statements for the Management of IBD in Pregnancy. Gastroenterology 2016;150:734-57.e1. [PubMed: 26688268]

- 4.

- van der Woude CJ, Ardizzone S, Bengtson MB, et al. The second European evidenced-based consensus on reproduction and pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:107-24. [PubMed: 25602023]

- 5.

- Flint J, Panchal S, Hurrell A, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part I: Standard and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:1693-7. [PubMed: 26750124]

- 6.

- Götestam Skorpen C, Hoeltzenbein M, Tincani A, et al. The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:795-810. [PubMed: 26888948]

- 7.

- Mottet C, Schoepfer AM, Juillerat P, et al. Experts opinion on the practical use of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:2733-47. [PubMed: 27760078]

- 8.

- Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1508-24. [PubMed: 30658060]

- 9.

- Vestergaard C, Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, et al. European task force on atopic dermatitis position paper: treatment of parental atopic dermatitis during preconception, pregnancy and lactation period. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:1644-59. [PubMed: 31231864]

- 10.

- Sammaritano LR, Bermas BL, Chakravarty EE, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Reproductive Health in Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:529-56. [PubMed: 32090480]

- 11.

- Russell MD, Dey M, Flint J, et al. British Society for Rheumatology guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding: Immunomodulatory anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2023;62:e48-e88. [PMC free article: PMC10070073] [PubMed: 36318966]

- 12.

- Laube R, Selinger CP, Seow CH, et al. Australian inflammatory bowel disease consensus statements for preconception, pregnancy and breast feeding. Gut 2023;72:1040-53. [PubMed: 36944479]

- 13.

- Torres J, Chaparro M, Julsgaard M, et al. European Crohn's and Colitis Guidelines on Sexuality, Fertility, Pregnancy, and Lactation. J Crohns Colitis 2023;17:1-27. [PubMed: 36005814]

- 14.

- Christensen LA, Dahlerup JF, Nielsen MJ, et al. Azathioprine treatment during lactation: Authors' reply. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:91. doi:.10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03996.x [PubMed: 18761704] [CrossRef]

- 15.

- Bar-Gil Shitrit, A, Grisaru-Granovsky S, Ben Ya'acov, A, Goldin E. Management of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:2194-204. [PubMed: 27068171]

- 16.

- Coulam CB, Moyer TP, Jiang NS, Zincke H. Breast-feeding after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc 1982;14:605-9. [PubMed: 6817481]

- 17.

- Kane SV, Present DH. Metabolites to immunomodulators are not detected in breast milk. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99 (10 Suppl. S):S246-7. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.001_1.x [CrossRef]

- 18.

- Moretti ME, Verjee Z, Ito S, Koren G. Breast-feeding during maternal use of azathioprine. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:2269-72. [PubMed: 17132809]

- 19.

- Sau A, Clarke S, Bass J, et al. Azathioprine and breastfeeding-is it safe? BJOG 2007;114:498-501. [PubMed: 17261122]

- 20.

- Christensen LA, Dahlerup JF, Nielsen MJ, et al. Azathioprine treatment during lactation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1209-13. [PubMed: 18761704]

- 21.

- Gardiner SJ, Gearry RB, Roberts RL, et al. Exposure to thiopurine drugs through breast milk is low based on metabolite concentrations in mother-infant pairs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:453-6. [PMC free article: PMC1885151] [PubMed: 16995866]

- 22.

- Bernard N, Garayt C, Chol F, et al. Prospective clinical and biological follow-up of three breastfed babies from azathioprine-treated mothers. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2007;21 (Suppl. 1):62-3. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00481.x [CrossRef]

- 23.

- Zelinkova Z, De Boer IP, van Dijke MJ, et al. Azathioprine treatment during lactation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:90-1. [PubMed: 19566905]

- 24.

- Grekas DM, Vasiliou SS, Lazarides AN. Immunosuppressive therapy and breast-feeding after renal transplantation. Nephron 1984;37:68. [PubMed: 6371564]

- 25.

- Madill JE, Levy G, Greig P. Pregnancy and breast-feeding while receiving cyclosporine A. In, Williams BAH, Sandiford-Guttenbeil DM, eds Trends in organ transplantation New York Springer Publishing Company 1996:109-21.

- 26.

- Nyberg G, Haljamae U, Frisenette-Fich C, et al. Breast-feeding during treatment with cyclosporine. Transplantation 1998;65:253-5. [PubMed: 9458024]

- 27.

- Muñoz-Flores-Thiagarajan KD, Easterling T, Davis C, Bond EF. Breast-feeding by a cyclosporine-treated mother. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:816-8. [PubMed: 11336764]

- 28.

- Gardiner SJ, Gearry RB, Roberts RL, et al. Comment: breast-feeding during maternal use of azathioprine. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:719-20. [PubMed: 17389671]

- 29.

- Khare MM, Lott J, Currie A, Howarth E. Is it safe to continue azathioprine in breast feeding mothers? J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;23 (Suppl 1):S48. doi:10.1080/718591746 [CrossRef]

- 30.

- Werner M, Bjornsson E, Prytz H, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis among fertile women: strategies during pregnancy and breastfeeding? Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:986-91. [PubMed: 17613929]

- 31.

- Angelberger S, Reinisch W, Messerschmidt A, et al. Long-term follow-up of babies exposed to azathioprine in utero and via breastfeeding. J Crohns Colitis 2011;5:95-100. [PubMed: 21453877]

- 32.

- de Meij TG, Jharap B, Kneepkens CM, et al. Long-term follow-up of children exposed intrauterine to maternal thiopurine therapy during pregnancy in females with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:38-43. [PubMed: 23675854]

- 33.

- Bernard N, Gouraud A, Paret N, et al. Azathioprine and breastfeeding: Long-term follow-up. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2013;27 (S1):12. doi:10.1111/fcp.12025 [CrossRef]

- 34.

- Matro R, Martin CF, Wolf D, et al. Exposure concentrations of infants breastfed by women receiving biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases and effects of breastfeeding on infections and development. Gastroenterology 2018;155:696-704. [PubMed: 29857090]

- 35.

- Beswick L, Shukla D, Friedman AB, et al. National audit: Assessing the use and safety of allopurinol thiopurine co-therapy in pregnant females with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31 (Suppl 2):128-9. doi:10.1111/jgh.13521 [CrossRef]

- 36.

- Klintmalm GB, Gunby RT, Jr. Successful pregnancy in a liver transplant recipient on belatacept. Liver Transpl 2020;26:1193-4. [PubMed: 32337853]

- 37.

- Boyle S, Sung-Him Mew T, Lust K, et al. Pregnancy following heart transplantation: A single centre case series and review of the literature. Heart Lung Circ 2021;30:144-53. [PubMed: 33162367]

- 38.

- Wakamatsu M, Muramatsu H, Kojima D, et al. A breast-fed baby with low KREC in TREC/KREC newborn screening whose mother received azathioprine treatment. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 2020;67 (Suppl 5):S46. doi:10.1002/pbc.28797 [CrossRef]

- 39.

- Ikram N, Eudy A, Clowse MEB. Breastfeeding in women with rheumatic diseases. Lupus Sci Med 2021;8:e000491. [PMC free article: PMC8039217] [PubMed: 33832977]

- 40.

- Reynolds JA, Gayed M, Khamashta MA, et al. Outcomes of children born to mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus exposed to hydroxychloroquine or azathioprine. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;62:1124-35. [PMC free article: PMC9977116] [PubMed: 35766806]

- 41.

- Uygur-Bayramiçli O, Aydin D, Ak O, Karadayi N. Hyperprolactinemia caused by azathioprine. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;36:79-80. [PubMed: 12488716]

- 42.

- Chaudhary D, Jhaj R. A case report on azathioprine-induced euprolactinemic galactorrhea. Indian J Pharmacol 2021;53:234-5. [PMC free article: PMC8262420] [PubMed: 34169910]

Substance Identification

Substance Name

Azathioprine

CAS Registry Number

446-86-6

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

- User and Medical Advice Disclaimer

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Record Format

- LactMed - Database Creation and Peer Review Process

- Fact Sheet. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed)

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Glossary

- LactMed Selected References

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - About Dietary Supplements

- Breastfeeding Links

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Review Mercaptopurine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Mercaptopurine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Thioguanine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Thioguanine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Cyclosporine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Cyclosporine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Cimetidine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Cimetidine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Ornidazole.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Ornidazole.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Azathioprine - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)Azathioprine - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...