Summary

Clinical characteristics.

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) (previously referred to as Fong's disease), encompasses the classic clinical tetrad of changes in the nails, knees, and elbows, and the presence of iliac horns. Nail changes are the most constant feature of NPS. Nails may be absent, hypoplastic, or dystrophic; ridged longitudinally or horizontally; pitted; discolored; separated into two halves by a longitudinal cleft or ridge of skin; and thin or (less often) thickened. The patellae may be small, irregularly shaped, or absent. Elbow abnormalities may include limitation of extension, pronation, and supination; cubitus valgus; and antecubital pterygia. Iliac horns are bilateral, conical, bony processes that project posteriorly and laterally from the central part of the iliac bones of the pelvis. Renal involvement, first manifest as proteinuria with or without hematuria, occurs in 30%-50% of affected individuals; end-stage kidney disease occurs up to 15% of affected individuals. Primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension occur at increased frequency and at a younger age than in the general population.

Diagnosis/testing.

The diagnosis of nail-patella syndrome is established in a proband with suggestive findings and/or a heterozygous pathogenic variant in LMX1B identified by molecular genetic testing

Management.

Treatment of manifestations: Orthopedic problems may be helped by analgesics, physiotherapy, splinting, bracing, or surgery; MRI of joints to identify abnormal anatomy is important prior to surgery so that appropriate surgical treatment can be planned in advance; ACE inhibitors to control blood pressure and possibly to slow progression of proteinuria; kidney transplantation as needed; standard treatment for decreased bone mineral density, hypertension, constipation/inflammatory bowel disease, glaucoma, epilepsy, and dental anomalies.

Surveillance: At least annually: monitoring of blood pressure for hypertension; assessment of urinalysis and first-morning urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio for kidney disease; screening for glaucoma (as soon as a child is compliant). Dental examination at least every six months and DXA scan as needed.

Agents/circumstances to avoid: Chronic use of NSAIDs because of the detrimental effect on kidney function.

Pregnancy management: The risk of developing preeclampsia may be increased in pregnant women with NPS; hence, frequent urinalysis and blood pressure measurement is recommended during pregnancy. For women taking an ACE inhibitor, transitioning to an alternative treatment ideally prior to pregnancy, or at least as soon as pregnancy is recognized, is recommended to avoid potential adverse effects of ACE inhibitors on the developing fetus.

Genetic counseling.

Nail-patella syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Eighty-eight percent of individuals with NPS have an affected parent; 12% of affected individuals have a de novo pathogenic variant. The offspring of an affected individual are at a 50% risk of inheriting NPS. Prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic testing are possible if the pathogenic variant in the family has been identified.

Diagnosis

Formal clinical diagnostic criteria for nail-patella syndrome (NPS) have not been published, although iliac horns (bilateral, conical, bony processes that project posteriorly and laterally from the central part of the iliac bones of the pelvis) are considered pathognomonic.

Suggestive Findings

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) should be suspected in individuals with the following clinical and radiologic findings.

Clinical findings

- Nail changes (see Figure 1), including nails that are:

- Absent, hypoplastic, or dystrophic

- Ridged longitudinally or horizontally

- Pitted

- Discolored

- Separated into two halves by a longitudinal cleft or ridge of skin

- Thin or (less often) thickened

- Limited to triangular lunules (lunulae), a characteristic feature of NPS

- Abnormal and unstable patella

- Small, irregularly shaped or absent patella as assessed by palpation or radiographs

- Recurrent subluxation or dislocation of the patella by history and/or physical exam

- Limitation of extension, pronation, and supination at the elbow; cubitus valgus; and antecubital pterygia

Radiologic findings

- Absent or hypoplastic patella that may be malpositionedNote: Patella ossification centers appear on radiographs between ages three and six years.

- Dysplasia of the radial head, hypoplasia of the lateral epicondyle and capitellum, and prominence of the medial epicondyle

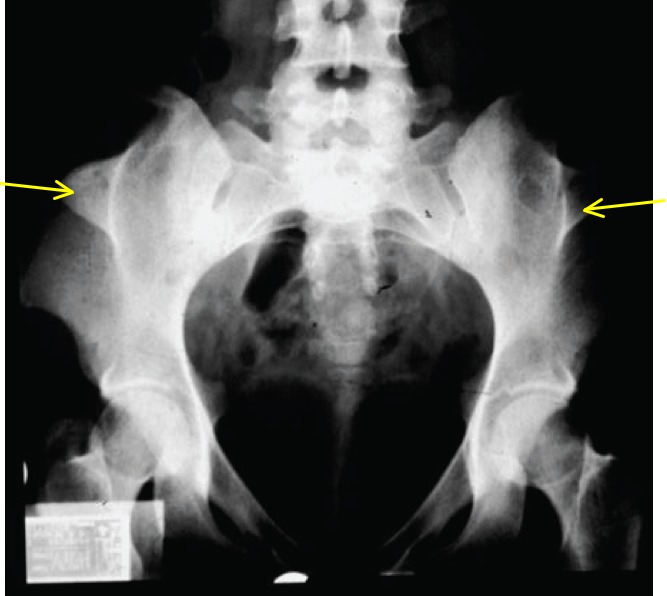

- Iliac horns (bilateral, conical, bony processes that project posteriorly and laterally from the central part of the iliac bones of the pelvis), which are considered pathognomonic of NPS (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Iliac horns (yellow arrows) in an individual with nail-patella syndrome

Family history is consistent with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Note: Absence of a known family history of NPS does not preclude the diagnosis.

Establishing the Diagnosis

The diagnosis of NPS is established in a proband with suggestive findings and/or a heterozygous pathogenic (or likely pathogenic) variant in LMX1B identified by molecular genetic testing (see Table 1).

Note: (1) Per ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines, the terms "pathogenic variant" and "likely pathogenic variant" are synonymous in a clinical setting, meaning that both are considered diagnostic and can be used for clinical decision making [Richards et al 2015]. Reference to "pathogenic variants" in this GeneReview is understood to include any likely pathogenic variants. (2) Identification of a heterozygous LMX1B variant of uncertain significance does not establish or rule out the diagnosis.

Molecular genetic testing approaches can include a combination of gene-targeted testing (single-gene testing, multigene panel) and comprehensive genomic testing (exome sequencing, exome array, genome sequencing) depending on the phenotype.

Gene-targeted testing requires that the clinician determine which gene(s) are likely involved, whereas genomic testing does not. Because the phenotype of nail-patella syndrome is broad, individuals with the distinctive findings described in Suggestive Findings are likely to be diagnosed using gene-targeted testing (see Option 1), whereas those in whom the diagnosis of nail-patella syndrome has not been considered are more likely to be diagnosed using genomic testing (see Option 2).

Option 1

Single-gene testing. Sequence analysis of LMX1B is performed first to detect missense, nonsense, and splice site variants and small intragenic deletions/insertions. Note: Depending on the sequencing method used, single-exon, multiexon, or whole-gene deletions/duplications may not be detected. If no variant is detected by the sequencing method used, the next step is to perform gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis to detect exon and whole-gene deletions or duplications.

Note: Pathogenic variants in an enhancer upstream of LMX1B were identified in individuals with nail and limb manifestations of NPS [Haro et al 2021, Francis et al 2023]. A chromosomal inversion interrupting LMX1B was identified in individuals with NPS from one family [Lindelöf et al 2022]. Genetic analysis for these variants could be pursued in individuals with clinical and radiographic findings of NPS but without an LMX1B pathogenic variant identified.

A multigene panel that includes LMX1B and other genes of interest (see Differential Diagnosis) is most likely to identify the genetic cause of the condition while limiting identification of variants of uncertain significance and pathogenic variants in genes that do not explain the underlying phenotype. This may be especially useful if kidney disease or glaucoma is the predominant presenting feature, as large multigene genetic testing panels for these disease groups are available. Note: (1) The genes included in the panel and the diagnostic sensitivity of the testing used for each gene vary by laboratory and are likely to change over time. (2) Some multigene panels may include genes not associated with the condition discussed in this GeneReview. (3) In some laboratories, panel options may include a custom laboratory-designed panel and/or custom phenotype-focused exome analysis that includes genes specified by the clinician. (4) Methods used in a panel may include sequence analysis, deletion/duplication analysis, and/or other non-sequencing-based tests. For this condition, a multigene panel that includes deletion/duplication analysis is recommended.

For an introduction to multigene panels click here. More detailed information for clinicians ordering genetic tests can be found here.

Option 2

When the diagnosis of nail-patella syndrome has not been considered because an individual has atypical phenotypic features, comprehensive genomic testing (which does not require the clinician to determine which gene is likely involved) may be considered. Exome sequencing is most commonly used; genome sequencing is also possible.

For an introduction to comprehensive genomic testing click here. More detailed information for clinicians ordering genomic testing can be found here.

Additional Testing Considerations for NPS

If targeted genetic testing or exome sequencing are not diagnostic, but NPS is clinically suspected and a dominant inheritance pattern is observed, karyotype may be considered. Chromosome translocations disrupting LMX1B have also been reported but represent a rare pathogenic mechanism [Duba et al 1998, Silahtaroglu et al 1999, Midro et al 2004].

Table 1.

Molecular Genetic Testing Used in Nail-Patella Syndrome

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical Description

The classic clinical tetrad of nail-patella syndrome (NPS) involves changes in the nails, knees, and elbows and the presence of iliac horns (see Diagnosis). Many other features may be seen in NPS, including kidney disease and glaucoma [Sweeney et al 2003]. The clinical manifestations are extremely variable in both frequency and severity, with inter- and intrafamilial variability. Individuals may be severely affected by one aspect of NPS but have much milder or no manifestations elsewhere. Though the skeleton is affected in NPS, affected individuals are of average stature.

To date, more than 170 pathogenic variants in LMX1B have been reported in individuals identified to have NPS [Lichter et al 1997, Bongers et al 2002, Sweeney et al 2003, Dunston et al 2005, Lemley 2009, López-Arvizu et al 2011, Boyer et al 2013, Ghoumid et al 2016, Harita et al 2020]. However, approximately 5%-10% of individuals with clinical and radiographic findings of NPS do not have a detectable pathogenic variant in LMX1B. The following description of the phenotypic features associated with this condition is based on these reports.

Table 2.

Select Features of Nail-Patella Syndrome

Nail changes are the most constant feature of NPS.

- Nail changes may be observed at birth and are most often bilateral and symmetric.

- The thumbnails are the most severely affected; the severity of the nail changes tends to decrease from the index finger toward the little finger.

- Each individual nail is usually more severely affected on its ulnar side.

- Dysplasia of the toenails is usually less marked and less frequent than that of the fingernails; if the toenails are involved, it is often the fifth toenail that is affected.

Digital changes. A reduction in flexion of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints is associated with loss of the creases in the skin overlying the dorsal surface of the DIP joints of the fingers.

- The gradient of severity is the same as seen in the nails; therefore, the index fingers are the most affected.

- Hyperextension of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints with flexion of the DIP joints (resulting in "swan-necking") and fifth-finger clinodactyly may also be seen.

Knee abnormalities. Symptoms include pain, instability, locking, clicking, patella dislocation, and inability to straighten the knee joint. Knee involvement may also be associated with poor development of the vastus medialis muscle.

- Patellae:

- Findings may be asymmetric.

- The patellae may be small, irregularly shaped, or absent.

- The displacement of the patella is lateral and superior; the hypoplastic patella is often located laterally and superiorly even when not actually dislocated.

- There may be prominent medial femoral condyles, hypoplastic lateral femoral condyles, and prominent tibial tuberosities.

- These changes together with a hypoplastic or absent patella give the knee joint a flattened profile.

- Flexion contractures of the knees may occur as a result of tight hamstring muscles.

- Osteochondritis dissecans, synovial plicae, and absence of the anterior cruciate ligament may also occur.

- Early degenerative arthritis is common.

Elbow involvement can include:

- Limitation of extension, pronation, and supination at the elbow

- Cubitus valgus

- Antecubital pterygia

Affected individuals may experience dislocation of the radial head, usually posteriorly. Elbow involvement may be asymmetric.

Illiac horns are considered pathognomonic of NPS [Sweeney et al 2003].

- Pelvic radiograph is usually necessary for their detection (Figure 2).

- Although large horns may be palpable, they are typically asymptomatic.

- Iliac horns may be seen on third-trimester ultrasound scanning [Feingold et al 1998], on radiograph at birth, and by bone scan [Goshen et al 2000].

- In children, iliac horns may have an epiphysis at the apex.

Involvement of the ankles and feet

- Talipes equinovarus, calcaneovarus, calcaneovalgus, equinovalgus, and hyperdorsiflexion of the foot may occur.

- Tight Achilles tendons are common, contributing to talipes equinovarus and to toe-walking.

- Pes planus is common.

Arthrogryposis. Though contractures of the elbows, knees, and calcaneovarus/calcaneovalgus are recognized in individuals with NPS, the term "arthrogryposis" is not often used in the clinical description of this condition.

- Sabir et al [2020] noted "arthrogryposis" as the presenting feature of an affected individual who underwent whole-exome sequencing.

- Because of limitations of phenotype search terms associated with established gene variants, LMX1B and NPS were not considered.

- By definition, arthrogryposis refers to multiple congenital, usually non-progressive joint contractures involving more than one joint; therefore, many people with NPS may be considered to have arthrogryposis (suggested by Sabir et al [2020] to be present in as many as 75% of individuals with NPS).

Spinal and chest wall problems. Back pain occurs in half of individuals with NPS. There may be an increased lumbar lordosis, scoliosis (usually mild), spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis, or pectus excavatum.

Osteoporosis. Bone mineral density is reduced by 8%-20% in the hips of individuals with NPS. An increased rate of fractures has also been reported.

General appearance. A lean body habitus may be associated with NPS and affected individuals often have difficulty putting on weight (particularly muscle) despite adequate dietary intake and exercise.

- In particular, muscle mass in the upper arms and upper legs tends to be decreased.

- The tendency to be very lean is most evident in adolescents and young adults and becomes less apparent after middle age.

- Increased lumbar lordosis may make the buttocks appear prominent.

- The high forehead and hairline, particularly at the temples, resembles a receding male pattern hairline when seen in women.

Renal involvement

- Renal involvement is present in 30%-50% of individuals with NPS. Variable rates of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) have been described as high as 15% by Lemley [2009], 5% by Sweeney et al [2003], and more recently, less than 5% by Harita et al [2020].

- The first sign of renal involvement is usually proteinuria, with or without hematuria.

- Proteinuria may present at any age from birth onwards and may be intermittent.

- Renal problems may present during (or be exacerbated by) pregnancy.

- Once proteinuria is present, it may remit spontaneously, remain asymptomatic, or progress to nephrotic syndrome and occasionally to ESKD.

- Steroids may not be effective in the treatment of proteinuria in individuals with NPS [Nakata et al 2017, Harita et al 2020]. See Genetic Steroid-Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome Overview, Clinical Characteristics.

- Progression to kidney failure may appear to occur rapidly or after many years of asymptomatic proteinuria. The factors responsible for this progression are yet to be identified but the presence and severity of proteinuria appears to be predictive of progression [Harita et al 2020]. In individuals with ESKD, kidney transplantation may be considered and typically has a favorable outcome (see Management, Treatment of Manifestations).

- Nephritis may also occur in NPS.

- Ultrastructural (electron microscopic) renal abnormalities are the most specific histologic changes seen in individuals with NPS and include irregular thickening of the glomerular basement membrane with electron-lucent areas giving a mottled "moth-eaten" appearance, and the presence of collagen-like fibers within the basement membrane and the mesangial matrix.

Ophthalmologic findings

- Primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension occur at increased frequency in NPS and at a younger age than in the general population [Lichter et al 1997, Sweeney et al 2003, Ghoumid et al 2016].

- Congenital and normal-tension glaucoma have also been reported in individuals with NPS [Lichter et al 1997].

- Iris pigmentary changes (termed Lester's sign) consisting of a zone of darker pigmentation shaped like a cloverleaf or flower around the central part of the iris are seen frequently.

Gastrointestinal involvement. One third of individuals with NPS have problems with constipation (often from birth) or irritable bowel syndrome [Sweeney et al 2003].

Neurologic problems. Many individuals with NPS exhibit reduced sensation to pain and temperature in the hands and feet, most likely because of the inability of Aδ and C fibers to connect with interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord [Dunston et al 2005]. Some affected individuals report intermittent numbness, tingling, and burning sensations in the hands and feet, with no obvious precipitant.

- Rarely, these symptoms may be secondary to local orthopedic problems or neurologic compromise from the spine or cervical ribs.

- In most cases, the paresthesia follows a glove and stocking pattern rather than the distribution of a particular dermatome or peripheral nerve.

Epilepsy was reported in 6% of affected individuals in one large study [Sweeney et al 2003].

Dental problems. Dental problems may include weak, crumbling teeth and thin dental enamel [Sweeney et al 2003].

Vasomotor problems. Some individuals have symptoms of a poor peripheral circulation, such as very cold hands and feet, even in warm weather. Some may be diagnosed with Raynaud's phenomenon [Sweeney et al 2003].

Vascular anomalies. There are limited reports of vascular anomalies in individuals with NPS, including internal carotid artery aplasia [Kraus et al 2020] and spontaneous coronary artery dissection [Nizamuddin et al 2015, Kaadan et al 2018]. The prevalence of vascular issues in a large population of individuals with NPS and the function of LMX1B in vessel formation must be studied further to determine if these findings are rare coincidental occurrences or part of the NPS phenotype. At this point, it is too early to know if this is part of the NPS phenotype.

Other. Congenital hip dislocation has been rarely reported [Jacofsky et al 2003, West & Louis 2015].

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

The majority (~80%) of pathogenic variants in LMX1B are found in the LIM domains.

Renal manifestations. Bongers et al [2005] suggested that individuals with a pathogenic variant in LMX1B in the LMX1 homeodomain showed significantly more frequent and higher values of proteinuria compared to those with pathogenic variants in the LIM domains. This observation is supported by Harita et al [2020] in a cohort of Japanese individuals with NPS. Thus far, it is not possible to predict progression of renal manifestations to end-stage kidney disease based on genotype alone because of inter-individual variability. However, the presence and severity of proteinuria appear to correlate with progression of kidney disease.

Non-renal manifestations. No clear genotype-phenotype association is apparent for extrarenal manifestations of NPS.

Nomenclature

Nail-patella syndrome is the most accepted term but has the disadvantage of implying that nail and patellar dysplasia are the most important features. Hereditary onycho-osteodysplasia (HOOD) may be more accurate, but is rarely used. Perhaps hereditary onycho-osteodysplasia with nephropathy and glaucoma would be the best term.

In the 2023 revision of the Nosology of Genetic Skeletal Disorders [Unger et al 2023], nail-patella syndrome is referred to as LMX1B-related nail-patella syndrome and is included in the patellar dysostoses group.

The terms Fong's disease and Turner syndrome have also been used.

- Captain EE Fong described the presence of unusual horn-like anomalies on the posterior aspect of the iliac bones in a woman undergoing an intravenous pyelogram. Fong published the description in 1946 and although he did not associate the anomaly with nail-patella syndrome, his name was connected to this condition [Fong 1946].

- Turner* and Keiser published earlier descriptions of the iliac horns in individuals with nail-patella syndrome in 1933 and 1939, respectively.* Note: Referring to JW Turner and not HH Turner, who described the phenotype associated with a 45,X karyotype

Prevalence

The prevalence of NPS has been roughly estimated at 1:50,000 but may be higher because of undiagnosed individuals with a mild phenotype.

Genetically Related (Allelic) Disorders

Pathogenic variants involving the same codon in LMX1B were identified in three families with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis without the extrarenal or ultrastructural manifestations of NPS [Boyer et al 2013]. No amino acid substitutions of this codon have been reported in individuals with NPS, suggesting that this codon is involved more specifically in binding to promoters of podocyte-expressed genes.

Differential Diagnosis

Table 3a.

Genes of Interest in the Differential Diagnoses of Nail-Patella Syndrome

Table 3b.

Chromosome Disorder and Hereditary Disorders of Unknown Genetic Cause in the Differential Diagnoses of Nail-Patella Syndrome

Management

Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis

To establish the extent of disease and needs in an individual diagnosed with nail-patella syndrome (NPS), the evaluations summarized in Table 4 (if not performed as part of the evaluation that led to the diagnosis) are recommended.

Table 4.

Recommended Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis in Individuals with Nail-Patella Syndrome

Treatment of Manifestations

Table 5.

Treatment of Manifestations in Individuals with Nail-Patella Syndrome

Surveillance

Table 6.

Recommended Surveillance for Individuals with Nail-Patella Syndrome

Agents/Circumstances to Avoid

Chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided because of their detrimental effect on kidney function.

Evaluation of Relatives at Risk

It is appropriate to clarify the genetic status of apparently asymptomatic older and younger at-risk relatives of an affected individual in order to identify as early as possible those who would benefit from prompt initiation of treatment and surveillance measures, particularly relating to ophthalmologic and renal manifestations. Evaluations can include:

- Molecular genetic testing if the pathogenic variant in the family is known;

- Monitoring renal findings (i.e., blood pressure, urinalysis, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio on a first-morning urine) and screening for glaucoma if the pathogenic variant in the family is not known.

See Genetic Counseling for issues related to testing of at-risk relatives for genetic counseling purposes.

Pregnancy Management

Renal problems may present during (or be exacerbated by) pregnancy. In one study 29% of pregnant women with NPS developed preeclampsia [Sweeney et al 2003]. Onset of nephrotic syndrome in pregnancy has also been described [Aboobacker et al 2018]. Hence, frequent urinalysis and blood pressure measurement is recommended in pregnant women with NPS. Medication used to treat kidney disease, such as ACE inhibitors, should be reviewed ideally prior to pregnancy, or at least as soon as pregnancy is recognized, so that transition to an alternative treatment can be considered in order to avoid potential adverse effects of ACE inhibitors on the developing fetus.

See MotherToBaby for further information on medication use during pregnancy.

Therapies Under Investigation

Search ClinicalTrials.gov in the US and EU Clinical Trials Register in Europe for access to information on clinical studies for a wide range of diseases and conditions. Note: There may not be clinical trials for this disorder.

Genetic Counseling

Genetic counseling is the process of providing individuals and families with information on the nature, mode(s) of inheritance, and implications of genetic disorders to help them make informed medical and personal decisions. The following section deals with genetic risk assessment and the use of family history and genetic testing to clarify genetic status for family members; it is not meant to address all personal, cultural, or ethical issues that may arise or to substitute for consultation with a genetics professional. —ED.

Mode of Inheritance

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

Risk to Family Members

Parents of a proband

- Eighty-eight percent of individuals diagnosed with NPS have an affected parent [Sweeney et al 2003].

- Twelve percent of individuals diagnosed with NPS have the disorder as the result of a de novo LMX1B pathogenic variant [Sweeney et al 2003].

- If the proband appears to be the only affected family member (i.e., a simplex case) and has a known LMX1B pathogenic variant, molecular genetic testing is recommended for the parents of the proband. If the causative pathogenic variant is not known, physical examination of the parents is recommended; however, it is possible that mild manifestations of NPS may not be readily apparent.

- If the pathogenic variant identified in the proband is not identified in either parent, the following possibilities should be considered:

- The proband has a de novo pathogenic variant. Note: A pathogenic variant is reported as "de novo" if: (1) the pathogenic variant found in the proband is not detected in parental DNA; and (2) parental identity testing has confirmed biological maternity and paternity. If parental identity testing is not performed, the variant is reported as "assumed de novo" [Richards et al 2015].

- The proband inherited a pathogenic variant from a parent with germline (or somatic and germline) mosaicism. Evidence of somatic and germline mosaicism has been reported in unaffected parents [Marini et al 2010]. Note: Testing of parental leukocyte DNA may not detect all instances of somatic mosaicism.

- The family history of some individuals diagnosed with NPS may appear to be negative because of failure to recognize the disorder in affected family members. Therefore, an apparently negative family history cannot be confirmed without appropriate clinical evaluation of the parents and/or molecular genetic testing (to establish that neither parent is heterozygous for the pathogenic variant identified in the proband).

- Note: If the parent is the individual in whom the pathogenic variant first occurred, the parent may have somatic mosaicism for the variant and may be mildly/minimally affected.

Sibs of a proband. The risk to the sibs of the proband depends on the genetic status of the proband's parents:

- If a parent of the proband is affected and/or is known to have the pathogenic variant identified in the proband, the risk to the sibs is 50%. NPS is fully penetrant in heterozygous individuals; however, the range and severity of manifestations may be extremely variable among affected family members.

- If the proband has a known LMX1B pathogenic variant that cannot be detected in the leukocyte DNA of either parent and/or both parents are clinically unaffected, the recurrence risk to sibs appears to be low but greater than that of the general population because of the possibility of parental mosaicism [Marini et al 2010].

Offspring of a proband. Each child of an individual with NPS has a 50% chance of inheriting the causative pathogenic variant.

Other family members. The risk to other family members depends on the status of the proband's parents: if a parent has the pathogenic variant, the parent's family members may be at risk.

Related Genetic Counseling Issues

See Management, Evaluation of Relatives at Risk for information on evaluating at-risk relatives for the purpose of early diagnosis and treatment.

Family planning

- The optimal time for determination of genetic risk and discussion of the availability of prenatal/preimplantation genetic testing is before pregnancy.

- It is appropriate to offer genetic counseling (including discussion of potential risks to offspring and reproductive options) to young adults who are affected or at risk.

Prenatal Testing and Preimplantation Genetic Testing

Molecular genetic testing. Once the LMX1B pathogenic variant has been identified in an affected family member, prenatal testing for a pregnancy at increased risk and preimplantation genetic testing are possible. Note: The clinical manifestations of NPS are variable and cannot be predicted based on family history or the presence of an LMX1B pathogenic variant identified on prenatal testing.

Ultrasound examination. Talipes equinovarus, other identifiable limb anomalies, or large iliac horns may be detected on fetal ultrasound examination in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Differences in perspective may exist among medical professionals and within families regarding the use of prenatal testing. While most centers would consider use of prenatal testing to be a personal decision, discussion of these issues may be helpful.

Resources

GeneReviews staff has selected the following disease-specific and/or umbrella support organizations and/or registries for the benefit of individuals with this disorder and their families. GeneReviews is not responsible for the information provided by other organizations. For information on selection criteria, click here.

- Nail Patella Syndrome WorldwideNail Patella Syndrome Worldwide is the official organization of the NPS Community.Email: info-npsw@npsw.org

Molecular Genetics

Information in the Molecular Genetics and OMIM tables may differ from that elsewhere in the GeneReview: tables may contain more recent information. —ED.

Table A.

Nail-Patella Syndrome: Genes and Databases

Table B.

OMIM Entries for Nail-Patella Syndrome (View All in OMIM)

Molecular Pathogenesis

Nail-patella syndrome is caused by pathogenic loss-of-function variants in LMX1B, encoding a transcription factor which directs dorso-ventral patterning of limb development and the formation of the anterior eye and the podocytes of the kidneys. This explains the phenotypic features of knee and elbow manifestations (early embryologic state of lower extremities positioned dorsally), glaucoma, and kidney disease associated with proteinuria. The role of the LMX1B protein product is less well understood in the cardiovascular and central nervous system, requiring further study.

The majority (~80%) of pathogenic variants in LMX1B are found in the LIM domains, with the rest in the homeodomain. There is variability in the phenotype between and within families, even with the same LMX1B pathogenic variant. For this reason, it is difficult to predict the disease severity based on the genotype. However, there appear to be more pathogenic variants in the homeodomain in individuals who have been described with kidney disease (see Genotype-Phenotype Correlations).

Pathogenic missense variants within the homeodomain reduce or eliminate DNA binding [Dreyer et al 1998, McIntosh et al 1998, Dreyer et al 2000, Bongers et al 2002]. Pathogenic missense variants within the LIM domains are believed to affect the secondary structure of the zinc fingers [McIntosh et al 1998, Clough et al 1999].

Mechanism of disease causation. NPS is the result of heterozygous loss-of-function pathogenic variants within the gene encoding the transcription factor. Bongers et al [2005] suggested a potential mechanism of disease of dominant-negative effect on the normal gene product, but this has not been replicated in subsequent studies.

LMX1B-specific laboratory technical considerations. All amino acid substitutions that have been observed cause NPS [Dunston et al 2004]. Missense variants are concentrated within the homeodomain and the residues in the LIM domains essential for maintaining the zinc finger structures. A series of recurrent variants within the homeodomain account for approximately 30% of all LMX1B pathogenic variants [Clough et al 1999]. No pathogenic variants have been identified in the terminal third of the gene.

Chapter Notes

Author Notes

The Greenberg Center for Skeletal Dysplasias in the Department of Genetic Medicine at Johns Hopkins University provides the diagnostic workup and management for patients with all forms of genetic skeletal disorders, including nail-patella syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients we have had the privilege to meet over the last decades through our clinical practice as well as patient support groups including Nail-Patella Syndrome Worldwide.

Revision History

- 14 December 2023 (jhf) Revision: information regarding pathogenic variants in an enhancer upstream of LMX1B added to Establishing the Diagnosis; congenital hip dislocation added to Clinical Description

- 11 May 2023 (sw) Revision: "LMX1B-Related Nail-Patella Syndrome" added as a synonym; Nosology of Genetic Skeletal Disorders: 2023 Revision [Unger et al 2023] added to Nomenclature

- 15 October 2020 (ma) Comprehensive update posted live

- 13 November 2014 (me) Comprehensive update posted live

- 28 July 2009 (me) Comprehensive update posted live

- 26 July 2005 (me) Comprehensive update posted live

- 31 May 2003 (me) Review posted live

- 14 April 2003 (im) Original submission

References

Literature Cited

- Aboobacker IN, Krishnakumar A, Narayanan S, Hafeeque B, Gopinathan JC, Aziz F. Nail-patella syndrome: a rare cause of nephrotic syndrome in pregnancy. Indian J Nephrol. 2018;28:76–8. [PMC free article: PMC5830815] [PubMed: 29515307]

- Bongers EM, de Wijs IJ, Marcelis C, Hoefsloot LH, Knoers NVAM. Identification of entire LMX1B gene deletions in nail patella syndrome: evidence for haploinsufficiency as the main pathogenic mechanism underlying dominant inheritance in man. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1240–4. [PubMed: 18414507]

- Bongers EM, Gubler MC, Knoers NV. Nail-patella syndrome. Overview on clinical and molecular findings. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:703–12. [PubMed: 12215822]

- Bongers EM, Huysmans FT, Levtchenko E, de Rooy JW, Blickman JG, Admiraal RJ, Huygen PL, Cruysberg JR, Toolens PA, Prins JB, Krabbe PF, Borm GF, Schoots J, van Bokhoven H, van Remortele AM, Hoefsloot LH, van Kampen A, Knoers NV. Genotype-phenotype studies in nail-patella syndrome show that LMX1B mutation location is involved in the risk of developing nephropathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:935–46. [PubMed: 15928687]

- Boyer O, Woerner S, Yang F, Oakeley EJ, Linghu B, Gribouval O, Tête M-J, Duca JS, Klickstein L, Damask AJ, Szustakowski JD, Heibel F, Matignon M, Baudouin V, Chantrel F, Champigneulle J, Martin L, Nitschké P, Gubler M-C, Johnson KJ, Chibout S-D, Antignac C. LMX1B mutations cause hereditary FSGS without extrarenal involvement. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1216–22. [PMC free article: PMC3736714] [PubMed: 23687361]

- Clough MV, Hamlington JD, McIntosh I. Restricted distribution of loss-of-function mutations within the LMX1B genes of nail-patella syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:459–65. [PubMed: 10571942]

- Dreyer SD, Morello R, German MS, Zabel B, Winterpacht A, Lunstrum GP, Horton WA, Oberg KC, Lee B. LMX1B transactivation and expression in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1067–74. [PubMed: 10767331]

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, Winterpacht A, Zabel B, Cole W, Johnson RL, Lee B. Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47–50. [PubMed: 9590287]

- Duba HC, Erdel M, Löffler J, Wirth J, Utermann B, Utermann G. Nail patella syndrome in a cytogenetically balanced t(9;17)(q34.1;q25) carrier. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:75–9. [PubMed: 9781017]

- Dunston JA, Hamlington JD, Zaveri J, Sweeney E, Sibbring J, Tran C, Malbroux M, O'Neill JP, Mountford R, McIntosh I. The human LMX1B gene: transcription unit, promoter, and pathogenic mutations. Genomics. 2004;84:565–76. [PubMed: 15498463]

- Dunston JA, Reimschisel T, Ding YQ, Sweeney E, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, McIntosh I. A neurological phenotype in nail patella syndrome (NPS) patients illuminated by studies of murine Lmx1b expression. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:330–5. [PubMed: 15562281]

- Feingold M, Itzchak Y, Goodman RM. Ultrasound prenatal diagnosis of the nail-patella syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:854–6. [PubMed: 9742578]

- Fong EE. Iliac horns (symmetrical bilateral central posterior iliac processes). Radiology. 1946;47:517. [PubMed: 20274622]

- Francis D, Lall P, Ayres S, Van Bergen NJ, Christodoulou J, Brown NJ, Kalitsis P. De novo enhancer deletion of LMX1B produces a mild nail-patella clinical phenotype. Clin Genet. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [PubMed: 37899549]

- Ghoumid J, Petit F, Holder-Espinasse M, Jourdain AS, Guerra J, Dieux-Coeslier A, Figeac M, Porchet N, Manouvrier-Hanu S, Escande F. Nail-patella syndrome: clinical and molecular data in 55 families raising the hypothesis of a genetic heterogeneity. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:44–50. [PMC free article: PMC4795216] [PubMed: 25898926]

- Goshen E, Schwartz A, Zilka LR, Zwas ST. Bilateral accessory iliac horns: pathognomonic findings in nail-patella syndrome. Scintigraphic evidence on bone scan. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:476–7. [PubMed: 10836702]

- Harita Y, Urae S, Akashio R, Isojima T, Miura K, Yamada T, Yamamoto K, Miyasaka Y, Furuyama M, Takemura T, Gotoh Y, Takizawa H, Tamagaki K, Ozawa A, Ashida A, Hattori M, Oka A, Kitanaka S. Clinical and genetic characterization of nephropathy in patients with nail-patella syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:1414–21. [PMC free article: PMC7608088] [PubMed: 32457516]

- Haro E, Petit F, Pira CU, Spady CD, Lucas-Toca S, Yorozuya LI, Gray AL, Escande F, Jourdain AS, Nguyen A, Fellmann F, Good JM, Francannet C, Manouvrier-Hanu S, Ros MA, Oberg KC. Identification of limb-specific Lmx1b auto-regulatory modules with Nail-patella syndrome pathogenicity. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5533. [PMC free article: PMC8452625] [PubMed: 34545091]

- Jacofsky DJ, Stans AA, Lindor NM. Bilateral hip dislocation and pubic diastasis in familial nail-patella syndrome. Orthopedics. 2003;26:329-30. [PubMed: 12650329]

- Jones KL. Trisomy 8 syndrome. In: Jones KL, ed. Smith's Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation. 7 ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013: 24-7.

- Kaadan MI, MacDonald C, Ponzini F, Duran J, Newell K, Pitler L, Lin A, Weinberg I, Wood MJ, Lindsay ME. Prospective cardiovascular genetics evaluation in spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e001933. [PubMed: 29650765]

- Kraus J, Jahngir MU, Singh B, Qureshi AI. Internal carotid artery aplasia in a patient with nail-patella syndrome. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2020;54:175–81. [PubMed: 31746280]

- Lemley KV. Kidney disease in nail-patella syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:2345–54. [PMC free article: PMC2770138] [PubMed: 18535845]

- Lichter PR, Richards JE, Downs CA, Stringham HM, Boehnke M, Farley FA. Cosegregation of open-angle glaucoma and the nail-patella syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:506–15. [PubMed: 9323941]

- Lindelöf H, Horemuzova E, Voss U, Nordgren A, Grigelioniene G, Hammarsjö A. Case report: inversion of LMX1B - a novel cause of nail-patella syndrome in a Swedish family and a longtime follow-up. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:862908. [PMC free article: PMC9235307] [PubMed: 35769074]

- López-Arvizu C, Sparrow EP, Strube MJ, Slavin C, DeOleo C, James J, Hoover-Fong J, McIntosh I, Tierney E. Increased symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and major depressive disorder symptoms in nail-patella syndrome: potential association with LMX1B loss of function. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:59–66. [PMC free article: PMC3677769] [PubMed: 21184584]

- Marini M, Bocciardi R, Gimelli S, Di Duca M, Divizia MT, Baban A, Gaspar H, Mammi I, Garavelli L, Cerone R, Emma F, Bedeschi MF, Tenconi R, Sensi A, Salmaggi A, Bengala M, Mari F, Colussi G, Szczaluba K, Antonarakis SE, Seri M, Lerone M, Ravazzolo R. A spectrum of LMX1B mutations in Nail-Patella syndrome: new point mutations, deletion, and evidence of mosaicism in unaffected parents. Genet Med. 2010;12:431–9. [PubMed: 20531206]

- McIntosh I, Dreyer SD, Clough MV, Dunston JA, Eyaid W, Roig CM, Montgomery T, Ala-Mello S, Kaitila I, Winterpacht A, Zabel B, Frydman M, Cole WG, Francomano CA, Lee B. Mutation analysis of LMX1B gene in nail-patella syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1651–8. [PMC free article: PMC1377636] [PubMed: 9837817]

- Midro AT, Panasiuk B, Tümer Z, Stankiewicz P, Silahtaroglu A, Lupski JR, Zemanova Z, Stasiewicz-Jarocka B, Hubert E, Tarasów E, Famulski W, Zadrozna-Tołwińska B, Wasilewska E, Kirchhoff M, Kalscheuer V, Michalova K, Tommerup N. Interstitial deletion 9q22.32-q33.2 associated with additional familial translocation t(9;17)(q34.11;p11.2) in a patient with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome and features of nail-patella syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;124A:179–91. [PubMed: 14699618]

- Nakata T, Ishida R, Mihara Y, Fuijii A, Inoue Y, Kusaba T, Isojima T, Harita Y, Kanda C, Kitanaka S, Tamagaki K. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome as the initial presentation of nail-patella syndrome: a case of a de novo LMX1B mutation. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:100. [PMC free article: PMC5363042] [PubMed: 28335748]

- Nizamuddin SL, Broderick DK, Minehart RD, Kamdar BB. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a parturient with Nail-Patella syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24:69–73. [PubMed: 25433575]

- Price A, Cervantes J, Lindsey S, Aickara D, Hu S. Nail-patella syndrome: clinical clues for making the diagnosis. Cutis. 2018;101:126–9. [PubMed: 29554154]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. [PMC free article: PMC4544753] [PubMed: 25741868]

- Sabir AH, Dermanis AA, Irving M, Cheung M. Arthrogryposis as a presenting feature of nail-patella syndrome: a lesser-known feature and the perils of negative whole-genome sequencing. Clin Dysmorphol. 2020;29:177–81. [PubMed: 32639239]

- Silahtaroglu A, Hol FA, Jensen PK, Erdel M, Duba HC, Geurds MP, Knoers NV, Mariman EC, Tumer Z, Utermann G, Wirth J, Bugge M, Tommerup N. Molecular cytogenetic detection of 9q34 breakpoints associated with nail patella syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:68–76. [PubMed: 10094193]

- Sweeney E, Fryer A, Mountford R, Green A, McIntosh I. Nail patella syndrome: a review of the phenotype aided by developmental biology. J Med Genet. 2003;40:153–62. [PMC free article: PMC1735400] [PubMed: 12624132]

- Tigchelaar S, Lenting A, Bongers EM, van Kampen A. Nail patella syndrome: knee symptoms and surgical outcomes. a questionnaire-based survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:959–962. [PubMed: 26596417]

- Towers AL, Clay CA, Sereika SM, McIntosh I, Greenspan SL. Skeletal integrity in patients with nail patella syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1961–5. [PubMed: 15623820]

- Unger S, Ferreira CR, Mortier GR, Ali H, Bertola DR, Calder A, Cohn DH, Cormier-Daire V, Girisha KM, Hall C, Krakow D, Makitie O, Mundlos S, Nishimura G, Robertson SP, Savarirayan R, Sillence D, Simon M, Sutton VR, Warman ML, Superti-Furga A. Nosology of genetic skeletal disorders: 2023 revision. Am J Med Genet A. 2023;191:1164–209. [PMC free article: PMC10081954] [PubMed: 36779427]

- West JA, Louis TH. Radiographic findings in the nail-patella syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015;28:334-6. [PMC free article: PMC4462213] [PubMed: 26130880]

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Liverpool, United Kingdom

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, Maryland

Department of Molecular & Cell Biology

American University of the Caribbean

St Maarten, Netherlands Antilles

Publication History

Initial Posting: May 31, 2003; Last Revision: December 14, 2023.

Copyright

GeneReviews® chapters are owned by the University of Washington. Permission is hereby granted to reproduce, distribute, and translate copies of content materials for noncommercial research purposes only, provided that (i) credit for source (http://www.genereviews.org/) and copyright (© 1993-2024 University of Washington) are included with each copy; (ii) a link to the original material is provided whenever the material is published elsewhere on the Web; and (iii) reproducers, distributors, and/or translators comply with the GeneReviews® Copyright Notice and Usage Disclaimer. No further modifications are allowed. For clarity, excerpts of GeneReviews chapters for use in lab reports and clinic notes are a permitted use.

For more information, see the GeneReviews® Copyright Notice and Usage Disclaimer.

For questions regarding permissions or whether a specified use is allowed, contact: ude.wu@tssamda.

Publisher

University of Washington, Seattle, Seattle (WA)

NLM Citation

Sweeney E, Hoover-Fong JE, McIntosh I. Nail-Patella Syndrome. 2003 May 31 [Updated 2023 Dec 14]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024.