NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-.

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood astrocytomas. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Date Last Modified") is the date of the most recent change. The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Childhood Glioma (including Astrocytoma)

Gliomas are a group of tumors that arise from glial cells in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). Glial cells support and protect the brain's nerve cells (also called neurons). They hold nerve cells in place, bring food and oxygen to nerve cells, and help protect nerve cells from disease, such as infection. Gliomas can form in any area of the CNS and can be low grade or high grade.

Other types of tumors can form in glial cells and nerve cells. Neuronal tumors are rare tumors made up of nerve cells. Glioneuronal tumors are a mix of nerve cells and glial cells. Neuronal and glioneuronal tumors are rare, low-grade tumors and are treated the same as gliomas.

Although cancer is rare in children, brain tumors are the second most common type of childhood cancer, after leukemia.

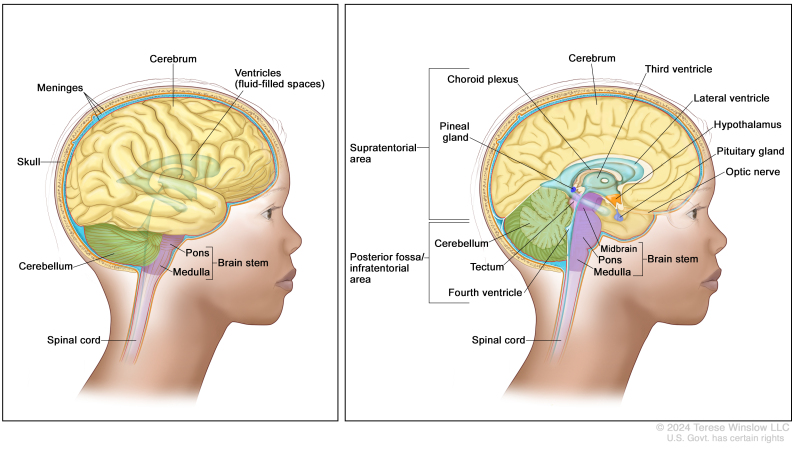

Gliomas are most common in these parts of the CNS:

- Cerebrum, the largest part of the brain, at the top of the head. The cerebrum controls thinking, learning, problem-solving, speech, emotions, reading, writing, and voluntary movement.

- Cerebellum, the lower, back part of the brain (near the middle of the back of the head). The cerebellum controls voluntary movement, balance, and posture.

- Brain stem, the part of the brain that is connected to the spinal cord. The brain stem is in the lowest part of the brain (just above the back of the neck). It controls breathing, heart rate, and the nerves and muscles used in seeing, hearing, walking, talking, and eating.

- Hypothalamus, the area in the middle of the base of the brain. It controls body temperature, hunger, and thirst.

- Visual pathway, the group of nerves that connect the eye with the brain.

- Spinal cord, the column of nerve tissue that runs from the brain stem down the center of the back. It is covered by three thin layers of tissue called membranes. The spinal cord and membranes are surrounded by the vertebrae (back bones). Spinal cord nerves carry messages between the brain and the rest of the body, such as a message from the brain to cause muscles to move or a message from the skin to the brain to feel touch.

Anatomy of the brain. The supratentorial area (the upper part of the brain) contains the cerebrum, lateral ventricle and third ventricle (with cerebrospinal fluid shown in blue), choroid plexus, pineal gland, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and optic nerve. The posterior fossa/infratentorial area (the lower back part of the brain) contains the cerebellum, tectum, fourth ventricle, and brain stem (midbrain, pons, and medulla). The skull and meninges protect the brain and spinal cord.

Types of glioma, neuronal, and glioneuronal tumors

Astrocytoma is the most common type of glioma diagnosed in children. It starts in a type of star-shaped glial cell called an astrocyte. Astrocytomas can form anywhere in the central nervous system.

Optic pathway glioma is a type of low-grade (slow-growing) glioma that can grow in children with a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

There are many types of astrocytomas, other gliomas, neuronal tumors, and glioneuronal tumors including:

- diffuse pediatric-type high-grade glioma

- infant-type hemispheric glioma

- diffuse low-grade glioma

- diffuse astrocytoma

- pilocytic astrocytoma

- high-grade astrocytoma with piloid features

- pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

- subependymal giant cell astrocytoma

- ganglioglioma

- desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma/desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma

- dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a type of high-grade glioma that forms in the brain stem and most often occurs in children. To learn more, see Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma.

Ependymoma is another type of tumor that can form from glial cells, but these tumors are not treated the same as gliomas. To learn more, see Childhood Ependymoma.

Causes and risk factors for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma)

Gliomas are caused by certain changes to the way glial cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of cell changes that lead to glioma is unknown. To learn more about how cancer develops, see What Is Cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with a risk factor will develop a glioma, and it will develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor. Inherited genetic disorders that may be risk factors for glioma include:

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk of a glioma.

Symptoms of childhood glioma (including astrocytoma)

The symptoms of childhood gliomas depend on the following factors:

- where the tumor forms in the brain or spinal cord

- the size of the tumor

- how fast the tumor grows

- your child's age and development

Some tumors do not cause symptoms while other tumors cause symptoms based on their location in the central nervous system. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has any symptoms below:

- morning headache or headache that goes away after vomiting

- nausea and vomiting

- vision, hearing, and speech problems

- loss of balance and trouble walking

- worsening handwriting or slow speech

- weakness or change in feeling on one side of the body

- unusual sleepiness

- more or less energy than usual

- change in personality or behavior

- seizures

- weight loss or weight gain for no known reason

- increase in the size of the head (in infants)

These symptoms may be caused by conditions other than childhood gliomas. The only way to know is to see your child's doctor.

Tests to diagnose childhood glioma (including astrocytoma)

If your child has symptoms that suggest a central nervous system tumor such as glioma, the doctor will need to find out if they are due to cancer or another condition. The doctor will ask you when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam, including a neurologic exam. Depending on these results, they may recommend tests to find out if your child has a central nervous system tumor.

The following tests may be used to diagnose a glioma, neuronal tumor, or glioneuronal tumor. The results will also help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without gadolinium

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of the brain and spinal cord. Sometimes a substance called gadolinium is injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) may be done during the same MRI scan to look at the chemical makeup of the brain tissue.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is a laboratory test that uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient's tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type of cancer. An MIB-1 test is a type of immunohistochemistry that checks tumor tissue for an antigen called MIB-1. This may show how fast a tumor is growing.

Molecular testing

A molecular test checks for certain genes, proteins, or other molecules in a sample of tissue, blood, or bone marrow. Molecular tests also check for certain changes in a gene or chromosome that may cause or affect the chance of developing a brain tumor. A molecular test may be used to help plan treatment, find out how well treatment is working, or make a prognosis.

The Molecular Characterization Initiative offers free molecular testing to children, adolescents, and young adults with certain types of newly diagnosed cancer. The program is offered through NCI's Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. To learn more, visit About the Molecular Characterization Initiative.

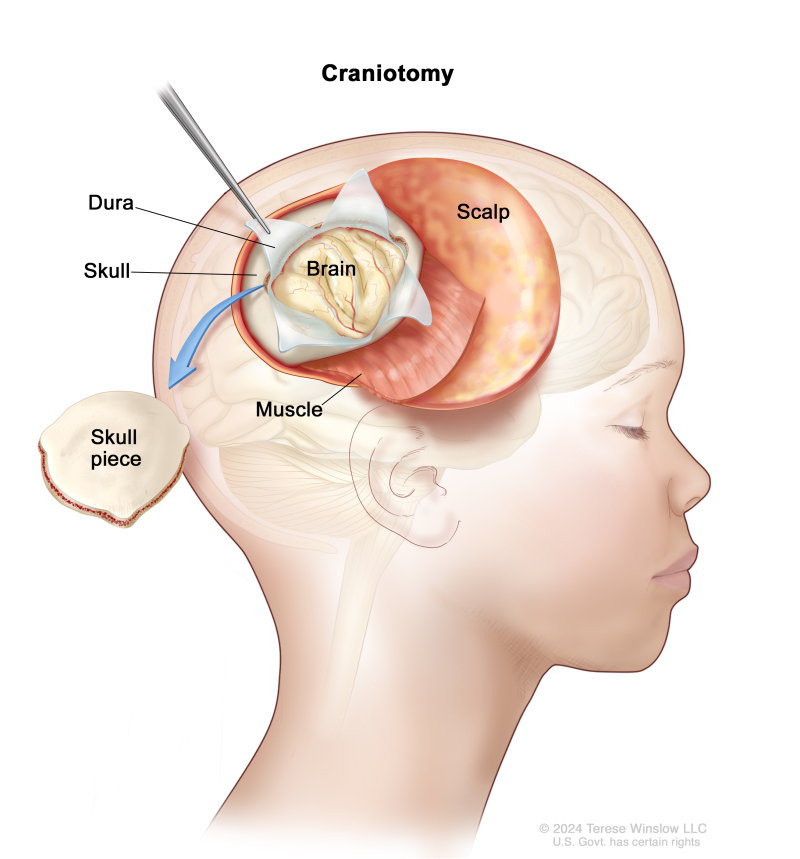

Surgery to diagnose and possibly remove the glioma

Your child might have surgery to diagnose or to remove all or part of the glioma. During the surgery, the surgeon removes a part of the skull, which gives an opening to remove the tumor. Sometimes scans are done during the procedure to help the surgeon locate the tumor and remove it. A pathologist will study the tumor under a microscope. If cancer cells are found, the surgeon may remove as much tumor as safely possible during the same surgery. The piece of skull is usually put back in place after the procedure.

Craniotomy. An opening is made in the skull and a piece of the skull is removed to show part of the brain.

Sometimes tumors form in a place that makes them hard to remove. If removing the tumor may cause severe physical, emotional, or learning problems, a biopsy is done and more treatment is given after the biopsy.

Children who have a rare genetic condition called neurofibromatosis type 1 may be at risk of a low-grade glioma called optic pathway glioma that forms in the area of the brain that controls vision. These children may not need a biopsy to diagnose the tumor. Surgery to remove the tumor may not be needed if the tumor does not grow and symptoms do not occur.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans. They may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes or another approach, or provide more information about your child's cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, see Finding Health Care Services. You can contact NCI's Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor or hospital that can provide a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your appointments, see Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Cancer.

Stages and tumor grades of childhood glioma (including astrocytoma)

Staging is the process of learning the extent of cancer in the body and is often used to help plan treatment and make a prognosis. There is no staging system used for childhood glioma, but it is given a tumor grade. Tumor grading is based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.

Tumor grade describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope, how quickly the tumor is likely to grow and spread within the central nervous system, and how likely the tumor is to come back after treatment.

There are four grades of gliomas, but they are most often grouped into low grade (grades I or II) or high grade (grades III or IV):

- Low-grade gliomas grow slowly and do not spread within the brain and spinal cord. But as they grow, they press on nearby healthy areas of the brain, affecting brain function. Most low-grade gliomas are treatable.

- High-grade gliomas are fast growing and often spread within the brain and spinal cord, which makes them harder to treat.

Childhood gliomas usually do not spread to other parts of the body.

Recurrent glioma

When a glioma comes back after it has been treated it is called a recurrent glioma. A glioma may come back in the same place as the first tumor or in other areas of the brain or spinal cord. Tests will be done to help determine if and where the cancer has returned. The type of treatment that your child will have for recurrent glioma will depend on where it came back.

Sometimes a low-grade glioma can come back as a high-grade glioma. High-grade gliomas often come back within 3 years either in the place where the cancer first formed or somewhere else in the brain or spinal cord.

Progressive childhood glioma is cancer that continues to grow, spread, or get worse. Progressive disease can be a sign that the cancer no longer responds to treatment.

Types of treatment for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma)

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with glioma. You and your child's cancer care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health, the tumor grade, and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, will oversee treatment. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with brain tumors and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's cancer care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, see our downloadable booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Surgery

Surgery is used to diagnose and treat childhood gliomas, as discussed in the Tests to diagnose childhood glioma (including astrocytoma) section of this summary. After surgery, an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is done to see if any cancer cells remain. If cancer cells are found, further treatment depends on:

- where the remaining cancer cells are

- the grade of the tumor

- your child's age

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some children may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy.

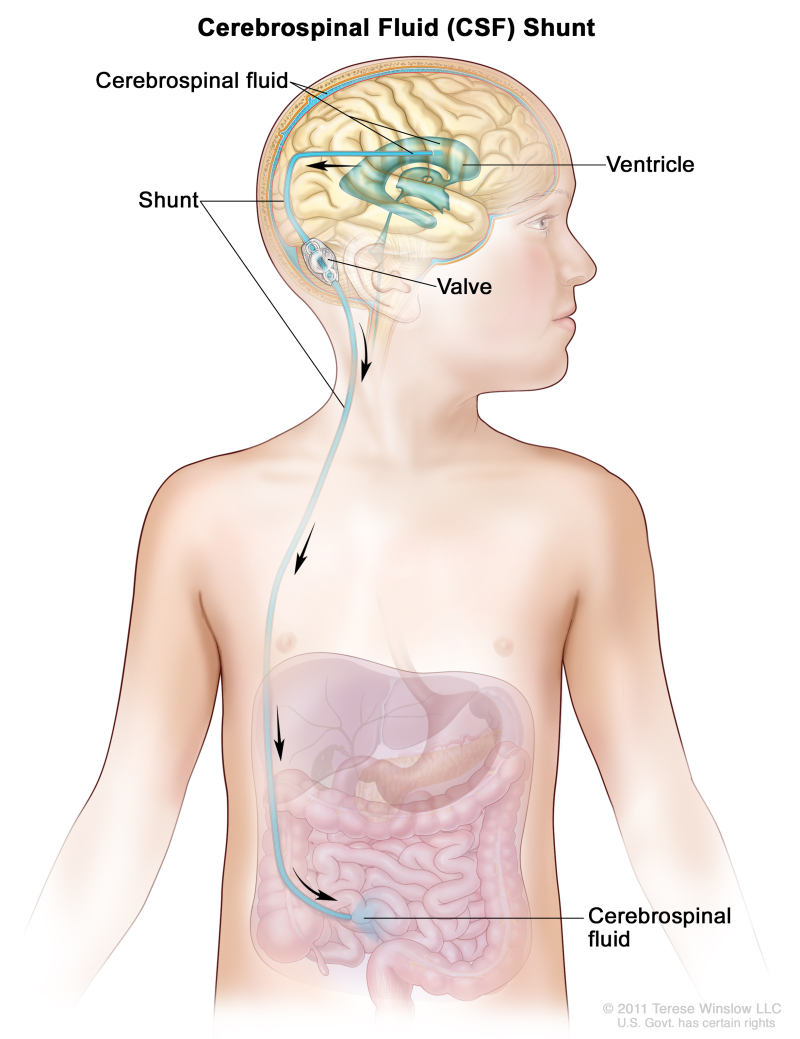

Sometimes children with a glioma have increased fluid around the brain or spinal cord. They may need surgery to place a shunt (long, thin tube) in a ventricle (fluid-filled space) of the brain and thread it under the skin to another part of the body, usually the abdomen. The shunt carries extra fluid away from the brain so it may be absorbed elsewhere in the body. This decreases the fluid and pressure on the brain or spinal cord. This process is called a CSF shunt.

A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt (a long, thin tube) carries extra CSF away from the brain so it may be absorbed elsewhere in the body. The shunt is placed in a ventricle (fluid-filled space) in the brain and threaded under the skin to another part of the body, usually the abdomen. The shunt has a valve that controls the flow of CSF.

Observation

Observation is closely monitoring a person's condition without giving any treatment or additional treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change. Observation may be used:

- if your child has no symptoms, such as children with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)

- if your child's tumor is small and is found when a different health problem is being diagnosed or treated

- after the tumor is removed by surgery until signs or symptoms appear or change

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment, such as radiation therapy.

To treat a glioma, chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy that may be used includes:

Combinations of these drugs may be used. Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about Chemotherapy to Treat Cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. Glioma may be treated with external beam radiation therapy. This type of treatment uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Radiation therapy may be given alone or with other treatments, such as chemotherapy.

Certain ways of giving external beam radiation therapy can help keep radiation from damaging nearby healthy tissue. These types of radiation therapy include:

- Conformal radiation therapy uses a computer to make a 3-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumor and shapes the radiation beams to fit the tumor. This allows a high dose of radiation to reach the tumor and causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) uses a computer to make 3-D pictures of the size and shape of the tumor. Thin beams of radiation of different intensities (strengths) are aimed at the tumor from many angles.

- Stereotactic radiation therapy uses a machine that aims radiation directly at the tumor causing less damage to nearby healthy tissue. The total dose of radiation is divided into several smaller doses given over several days. A rigid head frame is attached to the skull to keep the head still during the radiation treatment. This procedure is also called stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotaxic radiation therapy.

- Proton beam radiation therapy is a type of high-energy, external radiation therapy that uses streams of protons (tiny particles with a positive charge) to kill tumor cells. This type of treatment can lower the amount of radiation damage to healthy tissue near a tumor.

The way radiation therapy is given depends on the type of tumor and where the tumor formed in the brain or spinal cord.

Radiation therapy to the brain can affect growth and development, especially in young children. For children younger than 3 years, chemotherapy may be given instead, to delay or reduce the need for radiation therapy. Radiation therapy may also be delayed for patients with NF1 because they may be at increased risk for a second cancer.

To learn more, see External Beam Radiation Therapy for Cancer and Radiation Therapy Side Effects.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to block the action of specific enzymes, proteins, or other molecules involved in the growth and spread of cancer cells.

Targeted therapies that may be used or are being studied to treat glioma include:

Learn more about Targeted Therapy to Treat Cancer.

Clinical trials

A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for people with cancer. Because cancer in children is rare, taking part in a clinical trial should be considered.

Use our clinical trials search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

To learn more, see Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy helps a person's immune system fight cancer.

The following treatments are being studied to treat glioma:

- drugs that block the activity of PD-1

Learn more about how immunotherapy works against cancer, how it is given, and possible side effects, and more in Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer.

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood low-grade glioma, astrocytoma, neuronal, and glioneuronal tumors

Children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and a central nervous system tumor, children with an optic pathway glioma, or children who had a tumor found when getting a scan for another health problem may be observed (closely watched). These children may not receive treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change or the tumor grows.

Children with tuberous sclerosis may develop low-grade tumors in the brain called subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGAs). Targeted therapy with everolimus or sirolimus may be used instead of surgery, to shrink the tumors.

Children diagnosed with low-grade glioma are treated based on where the tumor is located. The first treatment is usually surgery. An MRI is done after surgery to see if any tumor remains. If the tumor was completely removed by surgery, more treatment may not be needed and the child is closely observed.

If there is tumor remaining after surgery, treatment may include:

- observation for children who had surgery to remove part of the tumor and the tumor is expected to regrow slowly

- combination chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy

- radiation therapy, which may include conformal radiation therapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, proton beam radiation therapy, or stereotactic radiation therapy, may be used if the tumor does not respond to chemotherapy or when the tumor begins to grow again

- a clinical trial of targeted therapy (selumetinib) with or without chemotherapy

To learn more about these treatments, see Types of treatment for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma).

Treatment of progressive or recurrent childhood low-grade glioma, astrocytoma, neuronal, or glioneuronal tumors

Childhood glioma, astrocytoma, glioneuronal, and neuronal tumors can be progressive or recurrent. They most often come back in the same area but can spread to other areas in the brain. Before more cancer treatment is given, imaging tests, biopsy, or surgery are done to find out if there is cancer, how much there is, and the grade.

Treatment of progressive or recurrent childhood low-grade glioma, astrocytoma, glioneuronal, and neuronal tumors may include:

- a second surgery to remove the tumor

- radiation therapy (including conformal radiation therapy), if radiation therapy was not used when the tumor was first diagnosed

- chemotherapy, if the tumor progressed or recurred where it cannot be removed by surgery

- targeted therapy (bevacizumab) with or without chemotherapy

- targeted therapy (everolimus or sirolimus)

- targeted therapy (dabrafenib and trametinib)

- a clinical trial of targeted therapy (selumetinib)

To learn more about these treatments, see Types of treatment for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma).

Treatment of childhood high-grade gliomas

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood high-grade glioma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy

- targeted therapy

- a clinical trial of targeted therapy with a combination of dabrafenib and trametinib after radiation therapy to treat newly diagnosed high-grade glioma that has mutations in the BRAF gene

- a clinical trial of immunotherapy

To learn more about these treatments, see Types of treatment for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma).

Treatment of recurrent childhood high-grade gliomas

Treatment of recurrent childhood high-grade glioma may include:

- second surgery depending on tumor type, location, and length of time between treatment and recurrence

- radiation therapy

- a clinical trial of targeted therapy

- a clinical trial of immunotherapy

To learn more about these treatments, see Types of treatment for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma).

Prognosis and prognostic factors for childhood glioma (including astrocytoma)

If your child has been diagnosed with a glioma, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis depends on many factors, including:

- whether the tumor is a low-grade or high-grade glioma

- where the tumor has formed in the central nervous system and if it has spread within the central nervous system or to other parts of the body

- how fast the tumor is growing

- your child's age

- whether cancer cells remain after surgery

- whether there are changes in certain genes such as BRAF

- whether your child has NF1 or tuberous sclerosis

- whether your child has diencephalic syndrome, a condition which slows physical growth

- whether the glioma has just been diagnosed or has come back after treatment

Children with a low-grade glioma, astrocytoma, neuronal tumor, or glioneuronal tumor have a relatively favorable prognosis if the tumor can be removed by surgery.

Children with a high-grade glioma have a poor prognosis. Some children diagnosed with a high-grade glioma, particularly infants younger than 1 year, may have tumors with certain fusion genes. Infants with a high-grade glioma whose tumors show these genetic changes may have a better prognosis than older children with a high-grade glioma.

For glioma that has come back after treatment, prognosis and treatment depend on how much time passed between the time treatment ended and the time the glioma came back.

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Side effects from the tumor and treatment

The signs or symptoms caused by the tumor may begin before diagnosis and continue for months or years. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about signs or symptoms caused by the tumor that may continue after treatment.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems that affect:

- -

vision, including blindness

- -

blood vessels

- -

hormone levels

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer)

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the effects cancer treatment can have on your child. To learn more, see Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or checkups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer will be repeated in order to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Regular MRIs will continue to be done after treatment has ended. The results of the MRI can show if your child's condition has changed or if the glioma has come back. If the results of the MRI show a mass in the brain, a biopsy may be done to find out if it is made up of dead tumor cells or if new cancer cells are growing.

Children who received radiation therapy to treat an optic pathway glioma are at risk of developing vision changes. These changes are most likely to occur within 2 years after radiation therapy. The effect of tumor growth and treatment on the child's vision will be closely followed during and after treatment.

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, see Support for Families When a Child Has Cancer and Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Related resources

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, see: