Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

3.1. INTRODUCTION

Learning Objectives

- Recognize nonverbal cues for physical and/or psychological stressors

- Provide patient education on stress management techniques

- Promote adaptive coping strategies

- Recognize the use of defense mechanisms

- Recognize a client in crisis

- Describe crisis intervention

Nurses support the emotional, mental, and social well-being of all clients experiencing stressful events and those with acute and chronic mental illnesses. [1] This chapter will review stressors, stress management, coping strategies, defense mechanisms, and crisis intervention.

References

- 1.

- NCSBN. (n.d.). Test plans. https://www

.ncsbn.org/testplans.htm.

3.2. STRESS

Everyone experiences stress during their lives. High levels of stress can cause symptoms like headaches, back pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Chronic stress contributes to the development of chronic illnesses, as well as acute physical illnesses due to decreased effectiveness of the immune system. It is important for nurses to recognize signs and symptoms of stress in themselves and others, as well as encourage effective stress management strategies. We will begin this section by reviewing the stress response and signs and symptoms of stress and then discuss stress management techniques.

Stress Response

Stressors are any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress. [1] The body’s sympathetic nervous system (SNS) responds to actual or perceived stressors with the “fight, flight, or freeze” stress response. Several reactions occur during the stress response that help the individual to achieve the purpose of either fighting or running. The respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems are activated to breathe rapidly, stimulate the heart to pump more blood, dilate the blood vessels, and increase blood pressure to deliver more oxygenated blood to the muscles. The liver creates more glucose for energy for the muscles to use to fight or run. Pupils dilate to see the threat (or the escape route) more clearly. Sweating prevents the body from overheating from excess muscle contraction. Because the digestive system is not needed during this time of threat, the body shunts oxygen-rich blood to the skeletal muscles. To coordinate all these targeted responses, hormones, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, and glucocorticoids (including cortisol, often referred to as the “stress hormone”), are released by the endocrine system via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and dispersed to the many SNS neuroreceptors on target organs simultaneously. [2] After the response to the stressful stimuli has resolved, the body returns to the pre-emergency state facilitated by the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) that has opposing effects to the SNS. See Figure 3.1 [3] for an image comparing the effects of stimulating the SNS and PNS.

Figure 3.1

SNS and PNS Simulation

Effects of Chronic Stress

The “fight or flight or freeze” stress response equips our bodies to quickly respond to life-threatening stressors. However, exposure to long-term stress can cause serious effects on the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems. [4] Consistent and ongoing increases in heart rate and blood pressure and elevated levels of stress hormones contribute to inflammation in arteries and can increase the risk for hypertension, heart attack, or stroke. [5]

During sudden onset stress, muscles contract and then relax when the stress passes. However, during chronic stress, muscles in the body are often in a constant state of vigilance that may trigger other reactions of the body and even promote stress-related disorders. For example, tension-type headaches and migraine headaches are associated with chronic muscle tension in the area of the shoulders, neck, and head. Musculoskeletal pain in the lower back and upper extremities has also been linked to job stress. [6]

Relaxation techniques and other stress-relieving activities have been shown to effectively reduce muscle tension, decrease the incidence of stress-related disorders, and increase a sense of well-being. For individuals with chronic pain conditions, stress-relieving activities have been shown to improve mood and daily function.[7]

During an acute stressful event, an increase in cortisol can provide the energy required to deal with prolonged or extreme challenges. However, chronic stress can result in an impaired immune system that has been linked to the development of numerous physical and mental health conditions, including chronic fatigue, metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, obesity), depression, and immune disorders. [8]

When chronically stressed, individuals may eat much more or much less than usual. Increased food, alcohol, or tobacco can result in acid reflux. Stress can induce muscle spasms in the bowel and can affect how quickly food moves through the gastrointestinal system, causing either diarrhea or constipation. Stress especially affects people with chronic bowel disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome. This may be due to the nerves in the gut being more sensitive, changes in gut microbiota, changes in how quickly food moves through the gut, and/or changes in gut immune responses. [9]

Excess amounts of cortisol can affect the normal biochemical functioning of the male reproductive system. Chronic stress can affect testosterone production, resulting in a decline in sex drive or libido, erectile dysfunction, or impotence. It can negatively impact sperm production and maturation, causing difficulties in couples who are trying to conceive. Researchers have found that men who experienced two or more stressful life events in the past year had a lower percentage of sperm motility and a lower percentage of sperm of normal morphology (size and shape) compared with men who did not experience any stressful life events. [10]

In the female reproductive system, stress affects menstruation and may be associated with absent or irregular menstrual cycles, more painful periods, and changes in the length of cycles. It may make premenstrual symptoms worse or more difficult to cope with, such as cramping, fluid retention, bloating, negative mood, and mood swings. Chronic stress may also reduce sexual desire. Stress can negatively impact a woman’s ability to conceive, the health of her pregnancy, and her postpartum adjustment. Maternal stress can negatively impact fetal development, disrupt bonding with the baby following delivery, and increase the risk of postpartum depression. [11]

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adults with adverse childhood experiences or exposure to adverse life events often experience ongoing chronic stress with an array of physical, mental, and social health problems throughout adulthood. Some of the most common health risks include physical and mental illness, substance use disorder, and a high level of engagement in risky sexual behavior. [12]

As previously discussed in Chapter 1, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, parental loss, or parental separation before the child is 18 years old. Individuals who have experienced four or more ACEs are at a significantly higher risk of developing mental, physical, and social problems in adulthood. Research has established that early life stress is a predictor of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug dependence. Adults who experienced ACEs related to maladaptive family functioning (parental mental illness, substance use disorder, criminality, family violence, physical and sexual abuse, and neglect) are at higher risk for developing mood, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders. ACEs are also associated with an increased risk of the development of malignancy, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and other chronic debilitating conditions. [13]

Signs and Symptoms of Stress

Nurses are often the first to notice signs and symptoms of stress and can help make their clients aware of these symptoms. Common signs and symptoms of chronic stress are as follows [14],[15]:

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Difficulty concentrating

- Rapid, disorganized thoughts

- Difficulty sleeping

- Digestive problems

- Changes in appetite

- Feeling helpless

- A perceived loss of control

- Low self-esteem

- Loss of sexual desire

- Nervousness

- Frequent infections or illnesses

- Vocalized suicidal thoughts

Stress Management

Recognizing signs and symptoms of stress allows individuals to implement stress management strategies. Nurses can educate clients about effective strategies for reducing the stress response. Effective strategies include the following [16],[17]:

- Set personal and professional boundaries

- Maintain a healthy social support network

- Select healthy food choices

- Engage in regular physical exercise

- Get an adequate amount of sleep each night

- Set realistic and fair expectations

Setting limits is essential for effectively managing stress. Individuals should list all of the projects and commitments making them feel overwhelmed, identify essential tasks, and cut back on nonessential tasks. For work-related projects, responsibilities can be discussed with supervisors to obtain input on priorities. Encourage individuals to refrain from accepting any more commitments until they feel their stress is under control. [18]

Maintaining a healthy social support network with friends and family can provide emotional support. [19] Caring relationships and healthy social connections are essential for achieving resilience.

Physical activity increases the body’s production of endorphins that boost the mood and reduce stress. Nurses can educate clients that a brisk walk or other aerobic activity can increase energy and concentration levels and lessen feelings of anxiety. [20]

People who are chronically stressed often suffer from lack of adequate sleep and, in some cases, stress-induced insomnia. Nurses can educate individuals how to take steps to increase the quality of sleep. Experts recommend going to bed at a regular time each night, striving for at least 7-8 hours of sleep, and, if possible, eliminating distractions, such as television, cell phones, and computers from the bedroom. Begin winding down an hour or two before bedtime and engage in calming activities such as listening to relaxing music, reading an enjoyable book, taking a soothing bath, or practicing relaxation techniques like meditation. Avoid eating a heavy meal or engaging in intense exercise immediately before bedtime. If a person tends to lie in bed worrying, encourage them to write down their concerns and work on quieting their thoughts. [21]

Nurses can encourage clients to set realistic expectations, look at situations more positively, see problems as opportunities, and refute negative thoughts to stay positive and minimize stress. Setting realistic expectations and positively reframing the way one looks at stressful situations can make life seem more manageable. Clients should be encouraged to keep challenges in perspective and do what they can reasonably do to move forward. [22]

Mindfulness is a form of meditation that uses breathing and thought techniques to create an awareness of one’s body and surroundings. Research suggests that mindfulness can have a positive impact on stress, anxiety, and depression. [23] Additionally, guided imagery may be helpful for enhancing relaxation. The use of guided imagery provides a narration that the mind can focus in on during the activity. For example, as the nurse encourages a client to use mindfulness and relaxation breathing, they may say, “As you breathe in, imagine waves rolling gently in. As you breathe out, imagine the waves rolling gently back out to sea.”

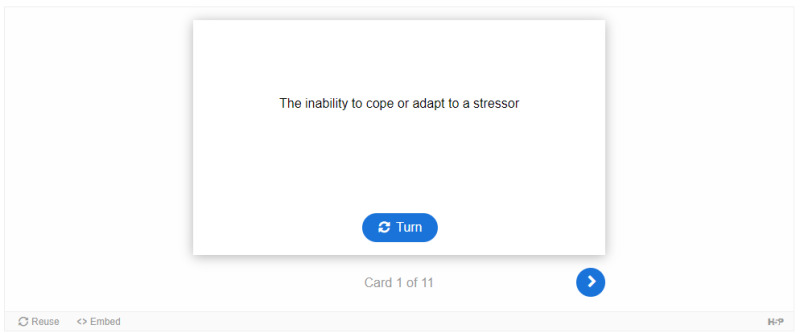

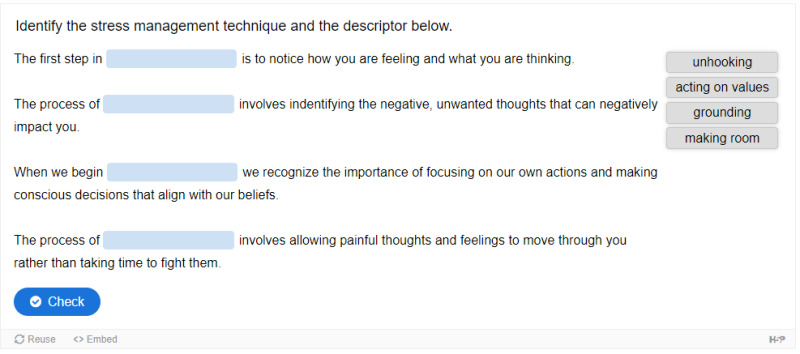

WHO Stress Management Guide

In addition to the stress management techniques discussed in the previous section, the World Health Organization (WHO) shares additional techniques in a guide titled Doing What Matters in Times of Stress. This guide is comprised of five categories. Each category includes techniques and skills that, based on evidence and field testing, can reduce overall stress levels even if only used for a few minutes each day. These categories include 1) Grounding, 2) Unhooking, 3) Acting on our values, 4) Being kind, and 5) Making room. [24]

Nurses can educate clients that powerful thoughts and feelings are a natural part of stress, but problems can occur if we get “hooked” by them. For example, one minute you might be enjoying a meal with family, and the next moment you get “hooked” by angry thoughts and feelings. Stress can make someone feel as if they are being pulled away from the values of the person they want to be, such as being calm, caring, attentive, committed, persistent, and courageous. [25]

There are many kinds of difficult thoughts and feelings that can “hook us,” such as, “This is too hard,” “I give up,” “I am never going to get this,” “They shouldn’t have done that,” or memories about difficult events that have occurred in our lives. When we get “hooked,” our behavior changes. We may do things that make our lives worse, like getting into more disagreements, withdrawing from others, or spending too much time lying in bed. These are called “away moves” because they move us away from our values. Sometimes emotions become so strong they feel like emotional storms. However, we can “unhook” ourselves by focusing and engaging in what we are doing, referred to as “grounding.” [26]

Grounding

“Grounding” is a helpful tool when feeling distracted or having trouble focusing on a task and/or the present moment. The first step of grounding is to notice how you are feeling and what you are thinking. Next, slow down and connect with your body by focusing on your breathing. Exhale completely and wait three seconds, and then inhale as slowly as possible. Slowly stretch your arms and legs and push your feet against the floor. The next step is to focus on the world around you. Notice where you are and what you are doing. Use your five senses. What are five things you can see? What are four things you can hear? What can you smell? Tap your leg or squeeze your thumb and count to ten. Touch your knees or another object within reach. What does it feel like? Grounding helps us engage in life, refocus on the present moment, and realign with our values. [27]

Unhooking

At times we may have unwanted, intrusive, negative thoughts that negatively affect us. “Unhooking” is a tool to manage and decrease the impact of these unwanted thoughts. First, NOTICE that a thought or feeling has hooked you, and then NAME it. Naming it begins by silently saying, “Here is a thought,” or “Here is a feeling.” By adding “I notice,” it unhooks us even more. For example, “I notice there is a knot in my stomach.” The next step is to REFOCUS on what you are doing, fully engage in that activity, and pay full attention to whoever is with you and whatever you are doing. For example, if you are having dinner with family and notice feelings of anger, note “I am having feelings of anger,” but choose to refocus and engage with family. [28]

Acting on Our Values

The third category of skills is called “Acting on Our Values.” This means, despite challenges and struggles we are experiencing, we will act in line with what is important to us and our beliefs. Even when facing difficult situations, we can still make the conscious choice to act in line with our values. The more we focus on our own actions, the more we can influence our immediate world and the people and situations we encounter every day. We must continually ask ourselves, “Are my actions moving me toward or away from my values?” Remember that even the smallest actions have impact, just as a giant tree grows from a small seed. Even in the most stressful of times, we can take small actions to live by our values and maintain or create a more satisfying and fulfilling life. These values should also include self-compassion and care. By caring for oneself, we ultimately have more energy and motivation to then help others. [29]

Being Kind

“Being Kind” is a fourth tool for reducing stress. Kindness can make a significant difference to our mental health by being kind to others, as well as to ourselves.

Making Room

“Making Room” is a fifth tool for reducing stress. Sometimes trying to push away painful thoughts and feelings does not work very well. In these situations, it is helpful to notice and name the feeling, and then “make room” for it. “Making room” means allowing the painful feeling or thought to come and go like the weather. Nurses can educate clients that as they breathe, they should imagine their breath flowing into and around their pain and making room for it. Instead of fighting with the thought or feeling, they should allow it to move through them, just like the weather moves through the sky. If clients are not fighting with the painful thought or feeling, they will have more time and energy to engage with the world around them and do things that are important to them. [30]

Read Doing What Matters in Times of Stress by the World Health Organization (WHO).

View the following YouTube video on the WHO Stress Management Guide [31]:

Stress Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic and World Events

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major effect on many people’s lives. Many health care professionals faced challenges that were stressful, overwhelming, and caused strong emotions. [32] See Figure 3.2 [33] for a message from the World Health Organization regarding stress and health care workers.

Figure 3.2

Stress and Healthcare Workers

Learning to cope with stress in a healthy way can increase feelings of resiliency for health care professionals. Here are ways to help manage stress resulting from world events [34]:

- Take breaks from watching, reading, or listening to news stories and social media. It’s good to be informed but consider limiting news to just a couple times a day and disconnecting from phones, TVs, and computer screens for a while.

- It can be important to do a self check-in before reading any news. “Do I have the emotional energy to handle a difficult headline if I see one?”

- Take care of your body.

- Take deep breaths, stretch, or meditate

- Try to eat healthy, well-balanced meals

- Exercise regularly

- Get plenty of sleep

- Avoid excessive alcohol, tobacco, and substance use

- Continue routine preventive measures (such as vaccinations, cancer screenings, etc.) as recommended by your health care provider

- Make time to unwind. Plan activities you enjoy.

- Purposefully connect with others. It is especially important to stay connected with your friends and family. Helping others cope through phone calls or video chats can help you and your loved ones feel less lonely or isolated. Connect with your community or faith-based organizations.

- Use the techniques described in the WHO stress management guide. [35]

Strategies for Self-Care

By becoming self-aware regarding signs of stress, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion [36]:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection and self-compassion prevent you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.

Many individuals have had to cope with grief and loss during the COVID pandemic. Read more about coping with grief and loss during COVID at the CDC’s Mental Health Grief and Loss webpage.

References

- 1.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 2.

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax

.org /books/anatomy-and-physiology /pages/1-introduction. - 3.

- Untitled image by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- 4.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 5.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 6.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 7.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 8.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 9.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 10.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 11.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 12.

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. 10.1177/2050312118782545. [PMC free article: PMC6024334] [PubMed: 29977550] [CrossRef]

- 13.

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. 10.1177/2050312118782545. [PMC free article: PMC6024334] [PubMed: 29977550] [CrossRef]

- 14.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 15.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 16.

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics/stress/body. - 17.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 18.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 19.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 20.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 21.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 22.

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www

.apa.org/topics /stress/chronic. - 23.

- Kandola, A. (2018, October 12). What are the health effects of chronic stress? MedicalNewsToday. https://www

.medicalnewstoday .com/articles/323324#treatment. - 24.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 25.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 26.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 27.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 28.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 29.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 30.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 31.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, November 4). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide [Video]. YouTube. Licensed in the Public Domain. https://youtu

.be/E3Cts45FNrk. - 32.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, December 2). Healthcare personnel and first responders: How to cope with stress and build resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www

.cdc.gov/coronavirus /2019-ncov /hcp/mental-health-healthcare.html. - 33.

- “89118597-2933268333403014-548082632068431872-n.jpg” by unknown author for World Health Organization (WHO) is licensed in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www

.who.int/campaigns /connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus /healthyathome /healthyathome---mental-health?gclid =Cj0KCQiA0MD_BRCTARIsADXoopa7YZldaIqCtKlGrxDV8YcUBtpVSD2HaOtT9NsdT8ajyCXbnPot-bsaAvlQEALw_wcB. - 34.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, December 2). Healthcare personnel and first responders: How to cope with stress and build resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www

.cdc.gov/coronavirus /2019-ncov /hcp/mental-health-healthcare.html. - 35.

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 36.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

3.3. COPING

The health consequences of chronic stress depend on an individual’s coping styles and their resilience to real or perceived stress. Coping refers to cognitive and behavioral efforts made to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts. [1]

Coping strategies are actions, a series of actions, or thought processes used in meeting a stressful or unpleasant situation or in modifying one’s reaction to such a situation. Coping strategies are classified as adaptive or maladaptive. Adaptive coping strategies include problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping typically focuses on seeking treatment such as counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy. Emotion-focused coping includes strategies such as mindfulness, meditation, and yoga; using humor and jokes; seeking spiritual or religious pursuits; engaging in physical activity or breathing exercises; and seeking social support.

Maladaptive coping responses include avoidance of the stressful condition, withdrawal from a stressful environment, disengagement from stressful relationships, and misuse of drugs and/or alcohol. [2] Nurses can educate individuals and their family members about adaptive, emotion-focused coping strategies and make referrals to interprofessional team members for problem-focused coping and treatment options for individuals experiencing maladaptive coping responses to stress.

Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies

Nurses can educate clients about many emotion-focused coping strategies, such as meditating, practicing yoga, journaling, praying, spending time in nature, nurturing supportive relationships, and practicing mindfulness.

Meditation

Meditation can induce feelings of calm and clearheadedness and improve concentration and attention. Research has shown that meditation increases the brain’s gray matter density, which can reduce sensitivity to pain, enhance the immune system, help regulate difficult emotions, and relieve stress. Meditation has been proven helpful for people with depression and anxiety, cancer, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, rheumatoid arthritis, type 2 diabetes, chronic fatigue syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. [3] See Figure 3.3 [4] for an image of an individual participating in meditation.

Figure 3.3

Meditation

Yoga

Yoga is a centuries-old spiritual practice that creates a sense of union within the practitioner through physical postures, ethical behaviors, and breath expansion. The systematic practice of yoga has been found to reduce inflammation and stress, decrease depression and anxiety, lower blood pressure, and increase feelings of well-being. [5] See Figure 3.4 [6] for an image of an individual participating in yoga.

Figure 3.4

Yoga

Journaling

Journaling can help a person become more aware of their inner life and feel more connected to experiences. Studies show that writing during difficult times may help a person find meaning in life’s challenges and become more resilient in the face of obstacles. When journaling, it can be helpful to focus on three basic questions: What experiences give me energy? What experiences drain my energy? Were there any experiences today where I felt alive and experienced “flow”? Allow yourself to write freely, without stopping to edit or worry about spelling and grammar. [7]

Prayer

Prayer can elicit the relaxation response, along with feelings of hope, gratitude, and compassion, all of which have a positive effect on overall well-being. There are several types of prayer rooted in the belief that there is a higher power. This belief can provide a sense of comfort and support in difficult times. A recent study found that adults who were clinically depressed who believed their prayers were heard by a concerned presence responded much better to treatment than those who did not believe. [8]

Individuals can be encouraged to find a spiritual community, such as a church, synagogue, temple, mosque, meditation center, or other local group that meets to discuss spiritual issues. The benefits of social support are well-documented, and having a spiritual community to turn to for fellowship can provide a sense of belonging and support. [9]

Spending Time in Nature

Spending time in nature is cited by many individuals as a spiritual practice that contributes to their mental health. [10] Spirituality is defined as a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. [11] Spiritual needs and spirituality are often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept. Other elements of spirituality include meaning, love, belonging, forgiveness, and connectedness. [12]

Supportive Relationships

Individuals should be encouraged to nurture supportive relationships with family, significant others, and friends. Relationships aren’t static – they are living, dynamic aspects of our lives that require attention and care. To benefit from strong connections with others, individuals should take charge of their relationships and devote time and energy to support them. It can be helpful to create rituals together. With busy schedules and the presence of online social media that offer the façade of real contact, it’s very easy to drift from friends. Research has found that people who deliberately make time for gatherings enjoy stronger relationships and more positive energy. An easy way to do this is to create a standing ritual that you can share and that doesn’t create more stress, such as talking on the telephone on Fridays or sharing a walk during lunch breaks. [13]

Mindfulness

Mindfulness has been defined as, “Awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” Mindfulness has also been described as, “Non-elaborative, nonjudgmental, present-centered awareness in which each thought, feeling, or sensation that arises is acknowledged and accepted as it is.” Mindfulness helps us be present in our lives and gives us some control over our reactions and repetitive thought patterns. It helps us pause, get a clearer picture of a situation, and respond more skillfully. Compare your default state to mindfulness when studying for an exam in a difficult course or preparing for a clinical experience. What do you do? Do you tell yourself, “I am not good at this” or “I am going to look stupid”? Does this distract you from paying attention to studying or preparing? How might it be different if you had an open attitude with no concern or judgment about your performance? What if you directly experienced the process as it unfolded, including the challenges, anxieties, insights, and accomplishments, while acknowledging each thought or feeling and accepting it without needing to figure it out or explore it further? If practiced regularly, mindfulness helps a person start to see the habitual patterns that lead to automatic negative reactions that create stress. By observing these thoughts and emotions instead of reacting to them, a person can develop a broader perspective and can choose a more effective response. [14]

Try free mindfulness activities at the Free Mindfulness Project.

Coping with Loss and Grief

In addition to assisting individuals recognize and cope with their stress and anxiety, nurses can also use this knowledge regarding coping strategies to support clients and their family members as they cope with life changes, grief, and loss that can cause emotional problems and feelings of distress.

Review concepts and nursing care related to coping with grief and loss in the “Grief and Loss” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

References

- 1.

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. 10.1177/2050312118782545. [PMC free article: PMC6024334] [PubMed: 29977550] [CrossRef]

- 2.

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. 10.1177/2050312118782545. [PMC free article: PMC6024334] [PubMed: 29977550] [CrossRef]

- 3.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality. - 4.

- “yoga-class-a-cross-legged-palms-up-meditation-position-850x831.jpg” by Amanda Mills, USCDCP on Pixnio is licensed under CC0.

- 5.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality. - 6.

- 7.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality. - 8.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality. - 9.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality. - 10.

- Yamada A., Lukoff D., Lim C. S. F., Mancuso L. L. Integrating spirituality and mental health: Perspectives of adults receiving public mental health services in California. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2020;12(3):276–287. [CrossRef]

- 11.

- Puchalski C. M., Vitillo R., Hull S. K., Reller N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014;17(6):642–656. [PMC free article: PMC4038982] [PubMed: 24842136] [CrossRef]

- 12.

- Rudolfsson G., Berggren I., da Silva A. B. Experiences of spirituality and spiritual values in the context of nursing - An integrative review. The Open Nursing Journal. 2014;8:64–70. [PMC free article: PMC4293736] [PubMed: 25598856] [CrossRef]

- 13.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality. - 14.

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www

.takingcharge .csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality.

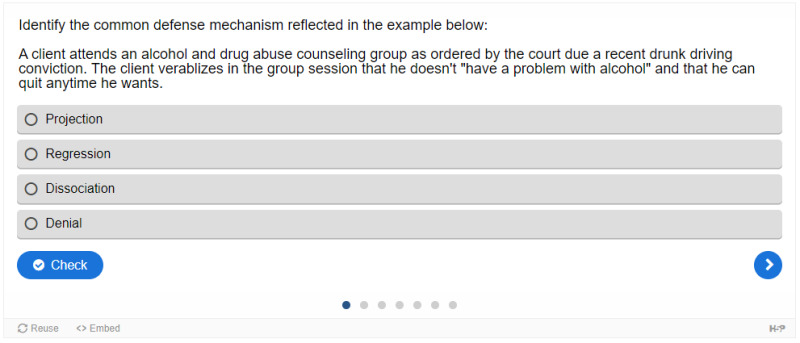

3.4. DEFENSE MECHANISMS

When providing clients with stress management techniques and effective coping strategies, nurses must be aware of common defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict. [1] Excessive use of defense mechanisms is associated with specific mental health disorders. With the exception of suppression, all other defense mechanisms are unconscious and out of the awareness of the individual. See Table 3.4 for a description of common defense mechanisms.

Table 3.4

Common Defense Mechanisms

References

- 1.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 2.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 3.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 4.

- Sissons, C. (2020, July 31). Defense mechanisms in psychology: What are they? MedicalNewsToday. https://www

.medicalnewstoday .com/articles/defense-mechanisms. - 5.

- Sissons, C. (2020, July 31). Defense mechanisms in psychology: What are they? MedicalNewsToday. https://www

.medicalnewstoday .com/articles/defense-mechanisms. - 6.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 7.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 8.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 9.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 10.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 11.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 12.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 13.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 14.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 15.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 16.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 17.

- Sissons, C. (2020, July 31). Defense mechanisms in psychology: What are they? MedicalNewsToday. https://www

.medicalnewstoday .com/articles/defense-mechanisms. - 18.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 19.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 20.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org.

3.5. CRISIS AND CRISIS INTERVENTION

If you were asked to describe someone in crisis, what would come to your mind? Many of us might draw on traditional images of someone anxiously wringing their hands, pacing the halls, having a verbal outburst, or acting erratically. Health care professionals should be aware that crisis can be reflected in these types of behaviors, but it can also be demonstrated in various verbal and nonverbal signs. There are many potential causes of crisis, and there are four phases an individual progresses through to crisis. Nurses and other health care professionals are often the frontline care providers when an individual faces a crisis, so it is important to recognize signs of crisis, know what to assess, intervene appropriately, and evaluate crisis resolution.

Definition of Crisis

A crisis can be broadly defined as the inability to cope or adapt to a stressor. Historically, the first examination of crisis and development of formal crisis intervention models occurred among psychologists in the 1960s and 1970s. Although definitions of crisis have evolved, there are central tenets related to an individual’s stress management.

Consider the historical context of crisis as first formally defined in the literature by Gerald Caplan. Crisis was defined as a situation that produces psychological disequilibrium in an individual and constitutes an important problem in which they can’t escape or solve with their customary problem-solving resources. [1] This definition emphasized the imbalance created by situation stressors.

Albert Roberts updated the concept of crisis management in more recent years to include a reflection on the level of an individual’s dysfunction. He defined crisis as an acute disruption of psychological homeostasis in which one’s usual coping mechanisms fail with evidence of distress and functional impairment. [2] A person’s subjective reaction to a stressful life experience compromises their ability (or inability) to cope or function.

Causes of Crisis

A crisis can emerge for individuals due to a variety of events. It is also important to note that events may be managed differently by different individuals. For example, a stressful stimulus occurring for Patient A may not induce the same crisis response as it does for Patient B. Therefore, nurses must remain vigilant and carefully monitor each patient for signs of emerging crisis.

A crisis commonly occurs when individuals experience some sort of significant life event. These events may be unanticipated, but that is not always the case. An example of anticipated life events that may cause a crisis include the birth of a baby. For example, the birth (although expected) can result in a crisis for some individuals as they struggle to cope with and adapt to this major life change. Predictable, routine schedules from before the child was born are often completely upended. Priorities shift to an unyielding focus on the needs of the new baby. Although many individuals welcome this change and cope effectively with the associated life changes, it can induce crises in those who are unprepared for such a change.

Crisis situations are more commonly associated with unexpected life events. Individuals who experience a newly diagnosed critical or life-altering illness are at risk for experiencing a crisis. For example, a client experiencing a life-threatening myocardial infarction or receiving a new diagnosis of cancer may experience a crisis. Additionally, the crisis may be experienced by family and loved ones of the patient as well. Nurses should be aware that crisis intervention and the need for additional support may occur in these types of situations and often extend beyond the needs of the individual patient.

Other events that may result in crisis development include stressors such as the loss of a job, loss of one’s home, divorce, or death of a loved one. It is important to be aware that clustering of multiple events can also cause stress to build sequentially so that individuals can no longer successfully manage and adapt, resulting in crisis.

Categories of Crises

Due to a variety of stimuli that can cause the emergence of a crisis, crises can be categorized to help nurses and health care providers understand the crisis experience and the resources that may be most beneficial for assisting the client and their family members. Crises can be characterized into one of three categories: maturational, situational, or social crisis. Table 3.5a explains characteristics of the different categories of crises and provides examples of stressors associated with that category.

Table 3.5a

Categories of Crises

Phases of Crisis

The process of crisis development can be described as four distinct phases. The phases progress from initial exposure to the stressor, to tension escalation, to an eventual breaking point. These phases reflect a sequential progression in which resource utilization and intervention are critical for assisting a client in crisis. Table 3.5b describes the various phases of crisis, their defining characteristics, and associated signs and symptoms that individuals may experience as they progress through each phase.

Table 3.5b

Crisis Phases [3],[4]

Crisis Assessment

Nurses must be aware of the potential impact of stressors for their clients and the ways in which they may manifest in a crisis. The first step in assessing for crisis occurs with the basic establishment of a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship. Understanding who your patient is, what is occurring in their life, what resources are available to them, and their individual beliefs, supports, and general demeanor can help a nurse determine if a patient is at risk for ineffective coping and possible progression to crisis.

Crisis symptoms can manifest in various ways. Nurses should carefully monitor for signs of the progression through the phases of crisis such as the following:

- Escalating anxiety

- Denial

- Confusion or disordered thinking

- Anger and hostility

- Helplessness and withdrawal

- Inefficiency

- Hopelessness and depression

- Steps toward resolution and reorganization

When a nurse identifies these signs in a patient or their family members, it is important to carefully explore the symptoms exhibited and the potential stressors. Collecting information regarding the severity of the stress response, the individual’s or family’s resources, and the crisis phase can help guide the nurse and health care team toward appropriate intervention.

Crisis Interventions

Crisis intervention is an important role for the nurse and health care team to assist patients and families toward crisis resolution. Resources are employed, and interventions are implemented to therapeutically assist the individual in whatever phase of crisis they are experiencing. Depending on the stage of the crisis, various strategies and resources are used.

The goals of crisis intervention are the following:

- Identify, assess, and intervene

- Return the individual to a prior level of functioning as quickly as possible

- Lessen negative impact on future mental health

During the crisis intervention process, new skills and coping strategies are acquired, resulting in change. A crisis state is time-limited, usually lasting several days but no longer than four to six weeks.

Various factors can influence an individual’s ability to resolve a crisis and return to equilibrium, such as realistic perception of an event, adequate situational support, and adequate coping strategies to respond to a problem. Nurses can implement strategies to reinforce these factors.

Strategies for Crisis Phase 1 and 2

Table 3.5c describes strategies and techniques for early phases of a crisis that can help guide the individual toward crisis resolution.

Table 3.5c

Phase 1 & 2 Early Crisis Intervention Strategies [5]

Strategies for Crisis Phase 3

If an individual continues to progress in severity to higher levels of crisis, the previously identified verbal and nonverbal interventions for Phase 1 and Phase 2 may be received with a variability of success. For example, for a receptive individual who is still in relative control of their emotions, the verbal and nonverbal interventions may still be well-received. However, if an individual has progressed to Phase 3 with emotional lability, the nurse must recognize this escalation and take additional measures to protect oneself. If an individual demonstrates loss of problem-solving ability or the loss of control, the nurse must take measures to ensure safety for themselves and others in all interactions with the patient. This can be accomplished by calling security or other staff to assist when engaging with the patient. It is important to always note the location of exits in the patient’s room and ensure the patient is never between the nurse and the exit. Rapid response devices may be worn, and nurses should feel comfortable using them if a situation begins to escalate.

Verbal cues can still hold significant power even in a late phase of crisis. The nurse should provide direct cues to an escalating patient such as, “Mr. Andrews, please sit down and take a few deep breaths. I understand you are angry. You need to gain control of your emotions, or I will have to call security for assistance.” This strategy is an example of limit-setting that can be helpful for de-escalating the situation and defusing tension. Setting limits is important for providing behavioral guidance to a patient who is escalating, but it is very different from making threats. Limit-setting describes the desired behavior whereas making threats is nontherapeutic. See additional examples contrasting limit-setting and making threats in the following box. [6]

Examples of Limit-Setting Versus Making Threats [7]

- Threat: “If you don’t stop, I’m going to call security!”

- Limit-Setting: “Please sit down. I will have to call for assistance if you can’t control your emotions.”

- Threat: “If you keep pushing the call button over and over like that, I won’t help you.”

- Limit-Setting: “Ms. Ferris, I will come as soon as I am able when you need assistance, but please give me a chance to get to your room.”

- Threat: “That type of behavior won’t be tolerated!”

- Limit-Setting: “Mr. Barron, please stop yelling and screaming at me. I am here to help you.”

Strategies for Crisis Phase 4

A person who is experiencing an elevated phase of crisis is not likely to be in control of their emotions, cognitive processes, or behavior. It is important to give them space so they don’t feel trapped. Many times these individuals are not responsive to verbal intervention and are solely focused on their own fear, anger, frustration, or despair. Don’t try to argue or reason with them. Individuals in Phase 4 of crisis often experience physical manifestations such as rapid heart rate, rapid breathing, and pacing.

If you can’t successfully de-escalate an individual who is becoming increasingly more agitated, seek assistance. If you don’t believe there is an immediate danger, call a psychiatrist, psychiatric-mental health nurse specialist, therapist, case manager, social worker, or family physician who is familiar with the person’s history. The professional can assess the situation and provide guidance, such as scheduling an appointment or admitting the person to the hospital. If you can’t reach someone and the situation continues to escalate, consider calling your county mental health crisis unit, crisis response team, or other similar contacts. If the situation is life-threatening or if serious property damage is occurring, call 911 and ask for immediate assistance. When you call 911, tell them someone is experiencing a mental health crisis and explain the nature of the emergency, your relationship to the person in crisis, and whether there are weapons involved. Ask the 911 operator to send someone trained to work with people with mental illnesses such as a Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) officer. [8]

A nurse who assesses a patient in this phase should observe the patient’s behaviors and take measures to ensure the patient and others remain safe. A person who is out of control may require physical or chemical restraints to be safe. Nurses must be aware of organizational policies and procedures, as well as documentation required for implementing restraints, if the patient’s or others’ safety is in jeopardy.

Review guidelines for safe implementation of restraints in the “Restraints” section of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Crisis Resources

Depending on the type of stressors and the severity of the crisis experienced, there are a variety of resources that can be offered to patients and their loved ones. Nurses should be aware of community and organizational resources that are available in their practice settings. Support groups, hotlines, shelters, counseling services, and other community resources like the Red Cross may be helpful. Read more about potential national and local resources in the following box.

Mental Health Crisis Resources

NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Health

ADRC of Central Wisconsin

Wisconsin County Crisis Lines

Wisconsin Suicide & Crisis Hotlines

Mental Health Crisis

When an individual is diagnosed with a mental health disorder, the potential for crisis is always present. Risk of suicide is always a priority concern for people with mental health conditions in crisis. Any talk of suicide should always be taken seriously. Most people who attempt suicide have given some warning. If someone has attempted suicide before, the risk is even greater. Read more about assessing suicide risk in the “Establishing Safety” section of Chapter 1. Encouraging someone who is having suicidal thoughts to get help is a safety priority.

Common signs that a mental health crisis is developing are as follows:

- Inability to perform daily tasks like bathing, brushing teeth, brushing hair, or changing clothes

- Rapid mood swings, increased energy level, inability to stay still, pacing, suddenly depressed or withdrawn, or suddenly happy or calm after period of depression

- Increased agitation with verbal threats; violent, out-of-control behavior or destruction of property

- Abusive behavior to self and others, including substance misuse or self-harm (cutting)

- Isolation from school, work, family, or friends

- Loss of touch with reality (psychosis) – unable to recognize family or friends, confused, doesn’t understand what people are saying, hearing voices, or seeing things that aren’t there

- Paranoia

Clients with mental illness and their loved ones need information for what to do if they are experiencing a crisis. Navigating a Mental Health Crisis: A NAMI Resource Guide for Those Experiencing a Mental Health Emergency provides important, potentially life-saving information for people experiencing mental health crises and their loved ones. It outlines what can contribute to a crisis, warning signs that a crisis is emerging, strategies to help de-escalate a crisis, and available resources.

References

- 1.

- Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventive psychiatry. Basic Books.

- 2.

- Roberts, A. R. (2005). Bridging the past and present to the future of crisis intervention and crisis management. In A. R. Roberts (Ed.), Crisis intervention handbook: Assessment, treatment, and research (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 3-34.

- 3.

- Caplan, G. (1964). Principles of preventive psychiatry. Basic Books.

- 4.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 25). The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety. https://www

.cdc.gov/niosh/ - 5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 25). The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety. https://www

.cdc.gov/niosh/ - 6.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 25). The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety. https://www

.cdc.gov/niosh/ - 7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 25). The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety. https://www

.cdc.gov/niosh/ - 8.

- Brister, T. (2018). Navigating a mental health crisis: A NAMI resource guide for those experiencing a mental health emergency. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www

.nami.org /Support-Education/Publications-Reports /Guides /Navigating-a-Mental-Health-Crisis /Navigating-A-Mental-Health-Crisis?utm _source =website&utm_medium =cta&utm_campaign =crisisguide.

3.6. APPLYING THE NURSING PROCESS TO STRESS AND COPING

This section will review the nursing process as it applies to stress and coping.

Assessments Related to Stress and Coping

Here are several nursing assessments used to determine an individual’s response to stress and their strategies for stress management and coping:

- Recognize nonverbal cues of physical or psychological stress

- Assess for environmental stressors affecting client care

- Assess for signs of abuse or neglect

- Assess client’s ability to cope with life changes

- Assess family dynamics

- Assess the potential for violence

- Assess client’s support systems and available resources

- Assess client’s ability to adapt to temporary/permanent role changes

- Assess client’s reaction to a diagnosis of acute or chronic mental illness (e.g., rationalization, hopefulness, anger)

- Assess constructive use of defense mechanisms by a client

- Assess if the client has successfully adapted to situational role changes (e.g., accept dependency on others)

- Assess client’s ability to cope with end-of-life interventions

- Recognize the need for psychosocial support to the family/caregiver

- Assess clients for maladaptive coping such as substance abuse

- Identify a client in crisis

Diagnoses Related to Stress and Coping

Nursing diagnoses related to stress and coping are Stress Overload and Ineffective Coping. See Table 3.6 to compare the definitions and defining characteristics for these nursing diagnoses.

Table 3.6

Stress and Coping Nursing Diagnoses

Outcomes Identification

An outcome is a measurable behavior demonstrated by the patient responsive to nursing interventions. Outcomes should be identified before nursing interventions are planned. Outcomes identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and then creating specific expected outcome statements for each nursing diagnosis. Goals are broad, general statements, and outcomes are specific and measurable. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the patient within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

Expected outcome statements should contain five components easily remembered using the “SMART” mnemonic:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable/Action oriented

- Relevant/Realistic

- Time frame

An example of a SMART outcome related to Stress Overload is, “The client will identify two stressors that can be modified or eliminated by the end of the week.”

An example of a SMART outcome related to Ineffective Coping is, “The client will identify three preferred coping strategies to implement by the end of the week.”

Read more information about establishing SMART outcome statements in the “Outcome Identification” section of Chapter 4.

Planning Interventions Related to Stress and Coping

Common nursing interventions that are implemented to facilitate effective coping in their clients include the following [1]:

- Implement measures to reduce environmental stressors

- Teach clients about stress management techniques and coping strategies

- Provide caring interventions for a client experiencing grief or loss, as well as resources to adjust to loss/bereavement

- Identify the client in crisis and tailor crisis intervention strategies to assist them to cope

- Guide the client to resources for recovery from crisis (i.e., social supports)

Implementation

When implementing nursing interventions to enhance client coping, it is important to recognize signs of a crisis and maintain safety for the client, oneself, and others. Review signs of a client in crisis and crisis intervention strategies in the “Crisis and Crisis Intervention” section of this chapter.

Evaluation

After implementing individualized interventions for a client, it is vital to evaluate their effectiveness. Review the specific SMART outcomes and deadlines that have been established for a client and determine if interventions were effective in meeting these outcomes or if the care plan requires modification.

References

- 1.

- NCSBN. (n.d.). Test plans. https://www

.ncsbn.org/testplans.htm.

III. GLOSSARY

- Adaptive coping strategies

Coping strategies, including problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping.

- Adverse childhood experiences

Potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, parental loss, or parental separation before the child is 18 years old.

- Coping

Cognitive and behavioral efforts made to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts. [1]

- Coping strategies

An action, series of actions, or a thought process used in meeting a stressful or unpleasant situation or in modifying one’s reaction to such a situation. [2]

- Crisis

The inability to cope or adapt to a stressor.

- Defense mechanisms

Unconscious reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict. [3]

- Emotion-focused coping

Adaptive coping strategies such as practicing mindfulness, meditation, and yoga; using humor and jokes; seeking spiritual or religious pursuits; engaging in physical activity or breathing exercises; and seeking social support.

- Maladaptive coping responses

Ineffective responses to stressors such as avoidance of the stressful condition, withdrawal from a stressful environment, disengagement from stressful relationships, and misuse of drugs and/or alcohol.

- Problem-focused coping

Adaptive coping strategies that typically focus on seeking treatment such as counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy.

- Stress response

The body’s physiological response to a real or perceived stressor. For example, the respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems are activated to breathe rapidly, stimulate the heart to pump more blood, dilate the blood vessels, and increase blood pressure to deliver more oxygenated blood to the muscles.

- Stressors

Any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress.

References

- 1.

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. 10.1177/2050312118782545. [PMC free article: PMC6024334] [PubMed: 29977550] [CrossRef]

- 2.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org. - 3.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary

.apa.org.

- Chapter 3 Stress, Coping, and Crisis Intervention - Nursing: Mental Health and C...Chapter 3 Stress, Coping, and Crisis Intervention - Nursing: Mental Health and Community Concepts

- Providing Healthy and Safe Foods As We AgeProviding Healthy and Safe Foods As We Age

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...