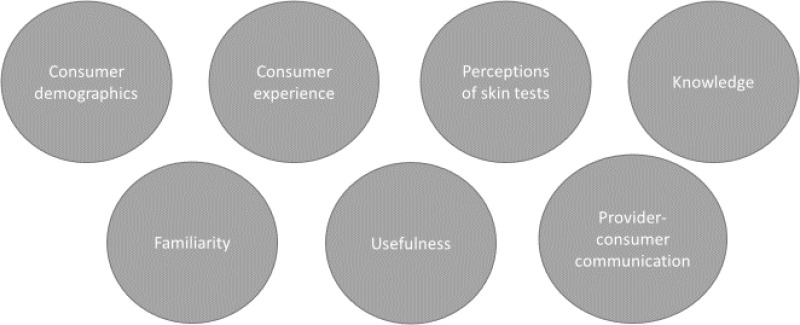

There were 7 subthemes relating to people factors for acceptability of TBI tests (). These included consumer experience, consumer demographics, perceptions of skin tests, knowledge, familiarity, and provider-consumer communication, which were discussed by both consumers and providers. Consumers also discussed how useful they perceived the test to be for themselves in terms of diagnosis and management of TBI – whereas this perceived usefulness of the test from a consumer perspective was not discussed by any health provider participants.

Consumer Experience

Several aspects of the consumer experience were found to affect the acceptability of TBI tests. All 3 TBI tests were reported to involve some discomfort during the procedure, including a slightly sore arm. Although, one consumer reported not finding blood tests uncomfortable.

“I had one many years ago and I remember it being quite uncomfortable… not invasive, that’s over, that’s too strong a word but yeah quite an uncomfortable test.” (ID001, HIC, Consumer)

In terms of the physical consequences of the tests, both the TBST and TST involve a welt on the arm. In rare cases, there may also be significant reactions from the intradermal injection. Moreover, the skin tests were reported to be painful tests at times due to the intradermal injection. Other participants did not perceive any physical consequences of TBST. No physical consequences were reported for the IGRA.

“…that’s a painful test, you know, in comparison with the IGRA, so that skin test, it’s very, it’s a painful test, it’s intradermal injection, it’s very painful.” (ID020, LMIC, Provider)

Mixed feedback was received regarding the psychological consequences of the tests. Some participants anticipated that there would be no psychological consequences of the TBST, while others anticipated that there may be additional anxiety associated with TBST due to these being a new test. For TBST and TST, anxiety may also be felt around the intradermal injection and the uncertainty of what the welt on the skin means. Some consumers reported feeling uneasy from the ‘live’ reading that took place in front of them, an experience that is avoided with the IGRA.

“We also found perspective from the patient that maybe people at the beginning, they worry that it’s painful and they scared of injection, but once they (indistinct), they like it very much because you can see physically the test result on your arm… at the beginning, many people worry about it, they worry that it would be unsafe, severe adverse reactions, and people would die if you injected PPD. Of course it’s not the case, there’s so many evidence in the world (indistinct) but they still worry, it took us a year to prove that it’s safe… It’s new things, injecting, people might even think that they are like, when you conduct clinical trial is the mice, they may be considered they are mice for the research.” (ID013, HIC, Provider)

“Psychologically, I would say yes, I would say that you’ve got, you can see and I, I mean I would totally go and Google and I would try to be diagnosing what was going on, and I would imagine that I guess you get some people who wouldn’t care, and so I imagine that a fair few people would actually, if they were interested in the outcome of the result, they might actually be concerned about what was going on in their arm and that might cause, psychological distress might be a little bit too strong word but a little bit of unease and uncertainty and apprehension I would say, because you can see what’s going on rather than it being a blood test taken away and it’s gone, it’s in a laboratory, you have no idea what’s going on.” (ID001, HIC, Consumer)

Moreover, in some cultures there is a stigma associated with the welt on the arm that a skin test may produce, and which an IGRA test can help to avoid. This stigma was raised as a serious concern in rural Indian communities:

“So some extent stigma can also be doing it like, so for these other tests they silently go to the lab and they’ll give the sample and come back. Here, this line or this mark is going to be for two days, so have attached, stigma attached to TB, so it could be a thing.” (ID005, LMIC, Provider)

Unique to the TST, the lower accuracy of this test could also prompt unnecessary stress for consumers from false positives:

“I think [the TBST are] more beneficial, it’s less strain on your mental health… [the existing tests are] probably not as reliable, not efficient (indistinct)… are they up to scratch, the results? There might be something wrong there.” (ID006, HIC, Consumer)

Anxiety was also reported as a consequence of the IGRA for consumers who are particularly uncomfortable with needles:

“Some patients may be absolutely, they’re completely terrified of having blood test but a skin test might be something they can cope with or who knows, I don’t know.” (ID012, HIC, Provider)

Some participants also reported that a hospital environment prompted feelings of anxiety. Although this environment is more commonplace for administration of the IGRA, it is possible that TST and TBST administrations may also take place in this environment.

Another aspect of the consumer experience that affected the acceptability of TBI tests was their degree of invasiveness. The IGRA was perceived to be more invasive than the TBST and TST. Moreover, certain cultures may be less comfortable with the degree of invasiveness that a blood sample requires.

“I feel like the need to sort of draw blood is a barrier for IGRA… it’s certainly a barrier when you’ve got to draw blood versus doing it via skin. I mean it’s not, I don’t, it is non-invasive to a certain degree but there is, it’s not like a breath test or peeing on a stick.” (ID017, HIC, Provider)

“Any test which is subcutaneous is fairer than intravenous because the blood test makes you draw out blood isn’t it?... Africans have some myth about people taking their blood.” (ID008, LMIC, Consumer)

Lastly, the complicated process involved with skin tests was perceived to reduce acceptability in consumers with low health literacy.

“First of all the test is a very complex thing, though to the provider it might be easy but from the patient’s perspective it is difficult. Like as of my understanding, patient should not have, should not rub on the injected areas and all those certain precautions need to be taken up. So to what extent patient keeps those things into mind is one end and this might require two visits to the test clinic. So from the patient perspective, I feel like it’s a bit complicated thing but not too much complicated if proper counselling is to be given to them.” (ID005, LMIC, Provider)

Demographics

Concerns were raised about the suitability of the IGRA and TBST for use in people with darker skin tones. One consumer described challenges they had faced with healthcare providers trying to find their veins for blood tests due to their darker skin tone, which reduces the acceptability of the IGRA in this population. However, concerns were also raised about whether accurate readings could be guaranteed for the TBST for persons with darker skin tones.

“Sometimes they can’t find my vein so it’s difficult to do blood tests… I know in most cases it’s easier to get a white person’s vein than a black person. So to me, I’ll go for the skin one and somebody else, so it’s not one size fit all.” (ID007, HIC, Consumer)

“Have they looked into the reading of the results with different skin types, different skin colours and can they guarantee that that’s accurate across all skin types, would be my other thought?” (ID001, HIC, Consumer)

All three tests were described as challenging for individuals with a needle phobia, with either a blood draw or an intradermal injection involved:

“Some patients also do not like injections. There are a number of patients who does not like injectables, so the moment you are inserting the needle, they feel very psychologically uneasy, so it brought a lot of problems.”

Researcher: “Is that even with the skin test, that they worry about the needle?”

Participant: “Yes.” (ID008, LMIC, Consumer):

Similar concerns were raised about placing intradermal injections in children, an experience that can be particularly challenging as it is more involved than a blood draw. Moreover, children were reported to struggle with the itchiness of the TST:

“I suppose with children particularly, it can be quite challenging cos obviously it’s a needle and it’s not a particularly quick injection either, so you can’t just sort of plunge it in and out.” (ID012, HIC, Provider)

“Well first of all it is kind of difficult to apply to the children because they move and also they tend to scratch the place that we put the TST.” (ID009, LMIC, Provider)

Provider-Consumer Communication

Both patients and providers felt that the acceptability of TBST could be improved through careful communication with consumers around test use. This could include describing the benefits of TBST over alternatives, and providing counseling to address any consumer concerns around the test (e.g., about the meaning of the skin mark).

“For me, it’s about perception. If from the initial stages, we market this product in a positive way, I think the perception by the outside, the general population will be good, but if for example, people begin to market in a negative way to say this skin test is also giving a problem in terms of once you are tested it leaves you maybe with a scar, it leaves you with this problem… then you will see that the public perception of the tests will be in the negative… I think we need to do a lot of, engage more community-based interventions in terms of promoting the new skin tests so that the public understanding of the new method is accepted.” (ID003, LMIC, Consumer)

“So this test to some extent would be an easy test to convince a patient if proper counseling is given to them because it is just an injection we are giving… if you counsel them properly, I don’t see any psychological and physical, I don’t see anything except the bulge which will be coming because of the test impact or the test reaction.” (ID005, LMIC, Provider)

“Certainly the introduction of novel skin tests required a lot of community education work. People needed to be explained about the usage of these tests and once they would be convinced, then this would abolish any potential psychological problem.” (ID016, LMIC, Provider)

Moreover, endorsement of the TBST by healthcare providers and organizations (e.g., the WHO) was expected to improve acceptability.

“I would like to think that if it was something that was being genuinely considered by World Health Organization and healthcare across the world as a suitable test, I would like to that that it’s a good one, it’s worth carrying on with.” (ID001, HIC, Consumer)