NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Chou R, Selph S, Blazina I, et al. Screening for Glaucoma in Adults: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2022 May. (Evidence Synthesis, No. 214.)

Screening for Glaucoma in Adults: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet].

Show detailsAppendix A1. Search Strategies

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R)

Screening

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,kf.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,kf.

- or/1-4

- Mass Screening/

- early diagnosis/

- screen*.ti,ab,kf.

- or/6-8

- 5 and 9

- limit 10 to yr=“2011 -Current”

- (random* or control* or trial or cohort or case* or prospective or retrospective or systematic or “meta analysis” or “metaanalysis”).ti,ab,kf,tw,pt,sh.

- 11 and 12

- limit 13 to english language

Referral

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,kf.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,kf.

- or/1-4

- exp “Referral and Consultation”/

- refer*.ti,ab,kw.

- 6 or 7

- 5 and 8

- (random* or control* or trial or cohort or case* or prospective or retrospective or systematic or “meta analysis” or “metaanalysis”).ti,ab,kf,tw,pt,sh.

- 9 and 10

- limit 11 to english language

Diagnostic Accuracy

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,kf.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,kf.

- or/1-4

- (screen* or test* or diagnos*).ti,ab,kf.

- 5 and 6

- exp “Sensitivity and Specificity”/

- (sensitivity or specificity or accuracy or predict* or reliability).ti,ab,kf.

- 8 or 9

- 7 and 10

- limit 11 to yr=“2011 -Current”

- limit 12 to english language

Treatment

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,kf.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,kf.

- or/1-4

- (apraclonidine or brimonidine or timolol or betaxolol or levobunolol or metipranolol or brinzolamide or methazolamide or dorzolamide or acetazolamide or travaprost or bimatoprost or latanoprost* or tafluprost or netarsudil).ti,ab,kf,sh.

- (“alpha 2 agonist*” or “alpha2 agonist*” or “beta blocker*” or “carbonic anahydrast inhibitor*” or “prostaglandin analogue*”).ti,ab,kf.

- (trabeculoplasty or trabeculectomy or phacotrabeculoplasty or phacotrabeculectomy).ti,ab,kf,sh.

- or/6-8

- 5 and 9

- limit 10 to yr=“2011 -Current”

- (random* or control* or trial or cohort or case* or prospective or retrospective or systematic or “meta analysis” or “metaanalysis”).ti,ab,kf,tw,pt,sh.

- 11 and 12

- limit 13 to english language

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

Screening

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,hw.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,hw.

- or/1-4

- Mass Screening/

- early diagnosis/

- screen*.ti,ab,hw.

- or/6-8

- 5 and 9

- limit 10 to yr=“2011 -Current”

- limit 11 to english language

- conference abstract.pt.

- “journal: conference abstract”.pt.

- “journal: conference review”.pt.

- 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17

- 12 not 18

Referral

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,hw.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,hw.

- or/1-4

- exp “Referral and Consultation”/

- refer*.ti,ab,hw.

- 6 or 7

- 5 and 8

- conference abstract.pt.

- “journal: conference abstract”.pt.

- “journal: conference review”.pt.

- 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14

- 9 not 15

- limit 16 to medline records

- 16 not 17

Diagnostic Accuracy

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,hw.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,hw.

- or/1-4

- (screen* or test* or diagnos*).ti,ab,hw.

- 5 and 6

- exp “Sensitivity and Specificity”/

- (sensitivity or specificity or accuracy or predict* or reliability).ti,ab,hw.

- 8 or 9

- 7 and 10

- limit 11 to yr=“2011 -Current”

- limit 12 to english language

- conference abstract.pt.

- “journal: conference abstract”.pt.

- “journal: conference review”.pt.

- 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18

- 13 not 19

Treatment

- Glaucoma, Open-Angle/

- glaucoma*.ti,ab,hw.

- Ocular Hypertension/

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab,hw.

- or/1-4

- (apraclonidine or brimonidine or timolol or betaxolol or levobunolol or metipranolol or brinzolamide or methazolamide or dorzolamide or acetazolamide or travaprost or bimatoprost or latanoprost* or tafluprost or netarsudil).ti,ab,hw,sh.

- (“alpha 2 agonist*” or “alpha2 agonist*” or “beta blocker*” or “carbonic anahydrast inhibitor*” or “prostaglandin analogue*”).ti,ab,hw.

- (trabeculoplasty or trabeculectomy or phacotrabeculoplasty or phacotrabeculectomy).ti,ab,hw,sh.

- or/6-8

- 5 and 9

- limit 10 to yr=“2011 -Current”

- limit 11 to english language

- conference abstract.pt.

- “journal: conference abstract”.pt.

- “journal: conference review”.pt.

- 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17

- 12 not 18

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

All KQs

- glaucoma*.ti,ab.

- “ocular hypertension”.ti,ab.

- “eyes and vision”.gw.

- 1 or 2

- 3 and 4

- limit 5 to last 10 years

- limit 6 to full systematic reviews

Appendix A2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Category | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of disease |

POAG; glaucoma defined by presence of glaucomatous optic disc changes and RNFL changes, with or without associated visual field changes or elevated IOP Glaucoma suspect: Patients do not meet criteria for glaucoma but have a consistently elevated IOP, a suspicious appearance of the optic nerve, or visual field abnormalities consistent with glaucoma | - |

| Populations |

KQs 1–5: Asymptomatic adults 40 years of age or older without visual symptoms KQs 6–11: Adults with screen-detected, asymptomatic, or early POAG |

KQs 1–5: Patients with visual symptoms, case-control studies of patients known to have OAG and normal controls KQs 6–11: Patients with OAG and severe visual field or visual deficits; patients with narrow-angle glaucoma, secondary glaucoma, juvenile glaucoma, other glaucoma |

| Interventions | KQs 1–2, 4–5: Screening with a comprehensive eye examination (as defined in the studies) by an eye health provider; screening tests performed in primary care or applicable to primary care; and instruments for identifying persons at increased risk of OAG KQ3: Referral to an eye specialist KQ4: Diagnostic tests that are currently used:

|

KQ4: Screening tests that are no longer used KQs 6–11: Second line medical therapies, surgery, argon trabeculoplasty, non-FDA approved therapies, therapies not commonly used as first-line therapy in U.S. practice |

| Comparisons |

KQ3: No referral KQs 4–5: Reference standard for OAG (as defined in the studies) KQs 6–11: Placebo, no therapy, or first-line medical therapies (for SLT, latanoprostene bunod, and netarsudil) |

Comparisons involving second line medical therapies or surgery Other eye in same patient as the control for diagnostic accuracy |

| Outcomes |

KQs 1–3, 6–11: IOP, visual field loss, VA, optic nerve damage, visual impairment (defined as VA <20/70 or <20/100), quality of life, function, harms (e.g., eye irritation, corneal abrasion, infection, anterior synechiae, cataracts) | Other (non-listed) outcomes |

| Timing | KQs 6–11: ≥4 weeks duration of followup | |

| Setting | Studies conducted in high income studies applicable to U.S. practice; include studies performed in primary care (including use of telemedicine) and specialty settings | |

| Study Design | RCTs of screening and treatment; cohort studies for harms of treatment if RCTs not available; population-based cohort or cross-sectional studies of diagnostic accuracy; high-quality systematic reviews | Case series, case reports, case-control studies |

| Study Quality | Fair or good-quality studies | Poor quality studies |

Abbreviations: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; GAT = Goldmann Applanation Tonometer; GCC = ganglion cell complex; IOP = intraocular pressure; OAG = open angle glaucoma; OCT = optical coherence tomography; POAG = primary open angle glaucoma; RCTs = randomized controlled trials; RNFL = retinal nerve fiber layer; SLT = selective laser trabeculoplasty; U.S. = United States; VA = visual acuity.

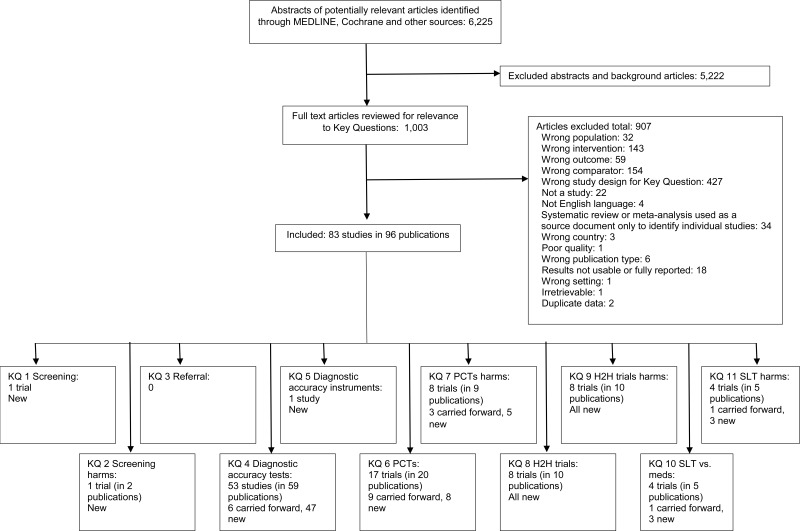

Appendix A3. Literature Flow Diagram

Appendix A4. Included Studies

- 1.

- Aksoy FE, Altan C, Yilmaz BS, et al. A comparative evaluation of segmental analysis of macular layers in patients with early glaucoma, ocular hypertension, and healthy eyes. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020;43(9):869–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2019.12.020. PMID: 32839014. [PubMed: 32839014] [CrossRef]

- 2.

- Aptel F, Sayous R, Fortoul V, et al. Structure-function relationships using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: comparison with scanning laser polarimetry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(6):825–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.06.011. PMID: 20851372. [PubMed: 20851372] [CrossRef]

- 3.

- Arnould L, De Lazzer A, Seydou A, et al. Diagnostic ability of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness to discriminate glaucoma patients from controls in an elderly population (the MONTRACHET study). Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98(8):e1009–e16. doi: 10.1111/aos.14448. PMID: 32333503. [PubMed: 32333503] [CrossRef]

- 4.

- Asrani S, Bacharach J, Holland E, et al. Fixed-dose combination of netarsudil and latanoprost in ocular hypertension and open-angle glaucoma: pooled efficacy/safety analysis of phase 3 MERCURY-1 and -2. Adv Ther. 2020;37(4):1620–31. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01277-2. PMID: 32166538. [PMC free article: PMC7140751] [PubMed: 32166538] [CrossRef]

- 5.

- Asrani S, Robin AL, Serle JB, et al. Netarsudil/Latanoprost fixed-dose combination for elevated intraocular pressure: three-month data from a randomized phase 3 trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;207:248–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.06.016. PMID: 31229466. [PubMed: 31229466] [CrossRef]

- 6.

- Azuara-Blanco A, Banister K, Boachie C, et al. Automated imaging technologies for the diagnosis of glaucoma: a comparative diagnostic study for the evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy, performance as triage tests and cost-effectiveness (GATE study). Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(8):1–168. doi: 10.3310/hta20080. PMID: 26822760. [PMC free article: PMC4781562] [PubMed: 26822760] [CrossRef]

- 7.

- Bagga H, Feuer WJ, Greenfield DS. Detection of psychophysical and structural injury in eyes with glaucomatous optic neuropathy and normal standard automated perimetry. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(2):169–76. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.169. PMID: 16476885. [PubMed: 16476885] [CrossRef]

- 8.

- Banister K, Boachie C, Bourne R, et al. Can automated imaging for optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer analysis aid glaucoma detection? Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):930–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.041. PMID: 27016459. [PMC free article: PMC4846823] [PubMed: 27016459] [CrossRef]

- 9.

- Bensinger RE, Keates EU, Gofman JD, et al. Levobunolol: a three-month efficacy study in the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(3):375–8. PMID: 3883971. [PubMed: 3883971]

- 10.

- Bergstrand IC, Heijl A, Harris A. Dorzolamide and ocular blood flow in previously untreated glaucoma patients: a controlled double-masked study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80(2):176–82. PMID: 11952485. [PubMed: 11952485]

- 11.

- Blumberg DM, De Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, et al. Technology and the glaucoma suspect. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(9):OCT80–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18931. PMID: 27409509. [PMC free article: PMC5995486] [PubMed: 27409509] [CrossRef]

- 12.

- Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, et al. The relationship between intraocular pressure and glaucoma in a defined population. Data from the Egna-Neumarkt Glaucoma Study. Ophthalmologica. 2001;215(1):34–8. doi: 10.1159/000050823. PMID: 11125267. [PubMed: 11125267] [CrossRef]

- 13.

- Brubaker JW, Teymoorian S, Lewis RA, et al. One year of netarsudil and latanoprost fixed-dose combination for elevated intraocular pressure: Phase 3, randomized MERCURY-1 study. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2020;3(5):327–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.05.008. PMID: 32768361. [PubMed: 32768361] [CrossRef]

- 14.

- Casado A, Cervero A, Lopez-de-Eguileta A, et al. Topographic correlation and asymmetry analysis of ganglion cell layer thinning and the retinal nerve fiber layer with localized visual field defects. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222347. PMID: 31509597. [PMC free article: PMC6738661] [PubMed: 31509597] [CrossRef]

- 15.

- Chan MPY, Broadway DC, Khawaja AP, et al. Glaucoma and intraocular pressure in EPIC-Norfolk Eye Study: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3889. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3889. PMID: 28903935. [PMC free article: PMC5596699] [PubMed: 28903935] [CrossRef]

- 16.

- Charalel RA, Lin HS, Singh K. Glaucoma screening using relative afferent pupillary defect. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(3):169–73. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31826a9742. PMID: 23296370. [PubMed: 23296370] [CrossRef]

- 17.

- Choudhari NS, George R, Baskaran M, et al. Can intraocular pressure asymmetry indicate undiagnosed primary glaucoma? The Chennai Glaucoma Study. J Glaucoma. 2013;22(1):31–5. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31822af25f. PMID: 21878819. [PubMed: 21878819] [CrossRef]

- 18.

- Cifuentes-Canorea P, Ruiz-Medrano J, Gutierrez-Bonet R, et al. Analysis of inner and outer retinal layers using spectral domain optical coherence tomography automated segmentation software in ocular hypertensive and glaucoma patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196112. PMID: 29672563. [PMC free article: PMC5908140] [PubMed: 29672563] [CrossRef]

- 19.

- Cumming RG, Ivers R, Clemson L, et al. Improving vision to prevent falls in frail older people: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):175–81. PMID: 17302652. [PubMed: 17302652]

- 20.

- Dabasia PL, Fidalgo BR, Edgar DF, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of technologies for glaucoma case-finding in a community setting. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.019. PMID: 26411836. [PubMed: 26411836] [CrossRef]

- 21.

- Danesh-Meyer HV, Gaskin BJ, Jayusundera T, et al. Comparison of disc damage likelihood scale, cup to disc ratio, and Heidelberg retina tomograph in the diagnosis of glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(4):437–41. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.077131. PMID: 16547323. [PMC free article: PMC1857000] [PubMed: 16547323] [CrossRef]

- 22.

- Deshpande G, Gupta R, Bawankule P, et al. Structural evaluation of preperimetric and perimetric glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(11):1843–9. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1955_18. PMID: 31638046. [PMC free article: PMC6836583] [PubMed: 31638046] [CrossRef]

- 23.

- Deshpande GA, Bawankule PK, Raje DV, et al. Linear discriminant score for differentiating early primary open angle glaucoma from glaucoma suspects. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(1):75–81. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_678_18. PMID: 30574897. [PMC free article: PMC6324090] [PubMed: 30574897] [CrossRef]

- 24.

- Ehrlich JR, Radcliffe NM, Shimmyo M. Goldmann applanation tonometry compared with corneal-compensated intraocular pressure in the evaluation of primary open-angle glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-12-52. PMID: 23009074. [PMC free article: PMC3514140] [PubMed: 23009074] [CrossRef]

- 25.

- Epstein DL, Krug JH, Jr., Hertzmark E, et al. A long-term clinical trial of timolol therapy versus no treatment in the management of glaucoma suspects. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(10):1460–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32688-1. PMID: 2685707. [PubMed: 2685707] [CrossRef]

- 26.

- Field MG, Alasil T, Baniasadi N, et al. Facilitating glaucoma diagnosis with intereye retinal nerve fiber layer asymmetry using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(2):167–76. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000080. PMID: 24921896. [PubMed: 24921896] [CrossRef]

- 27.

- Francis BA, Varma R, Vigen C, et al. Population and high-risk group screening for glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):6257–64. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5126. PMID: 21245400. [PMC free article: PMC3175989] [PubMed: 21245400] [CrossRef]

- 28.

- Garas A, Vargha P, Hollo G. Diagnostic accuracy of nerve fibre layer, macular thickness and optic disc measurements made with the RTVue-100 optical coherence tomograph to detect glaucoma. Eye. 2011;25(1):57–65. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.139. PMID: 20930859. [PMC free article: PMC3144640] [PubMed: 20930859] [CrossRef]

- 29.

- Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP, Bunce C, et al. Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9975):1295–304. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62111-5. PMID: 25533656. [PubMed: 25533656] [CrossRef]

- 30.

- Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10180):1505–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32213-x. PMID: 30862377. [PMC free article: PMC6495367] [PubMed: 30862377] [CrossRef]

- 31.

- Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus drops for newly diagnosed ocular hypertension and glaucoma: the LiGHT RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23(31):1–102. doi: 10.3310/hta23310. PMID: 31264958. [PMC free article: PMC6627009] [PubMed: 31264958] [CrossRef]

- 32.

- Gordon MO, Kass MA. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: design and baseline description of the participants. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(5):573–83. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.573. PMID: 10326953. [PubMed: 10326953] [CrossRef]

- 33.

- Hammond EA, Begley PK. Screening for glaucoma: a comparison of ophthalmoscopy and tonometry. Nurs Res. 1979;28(6):371–2. PMID: 258807. [PubMed: 258807]

- 34.

- Hark LA, Myers JS, Ines A, et al. Philadelphia telemedicine glaucoma detection and follow-up study: confirmation between eye screening and comprehensive eye examination diagnoses. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(12):1820–6. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313451. PMID: 30770354. [PubMed: 30770354] [CrossRef]

- 35.

- Hark LA, Myers JS, Pasquale LR, et al. Philadelphia telemedicine glaucoma detection and follow-up study: intraocular pressure measurements found in a population at high risk for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2019;28(4):294–301. PMID: 30946709. [PubMed: 30946709]

- 36.

- Heijl A, Bengtsson B. Long-term effects of timolol therapy in ocular hypertension: a double-masked, randomised trial. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238(11):877–83. doi: 10.1007/s004170000189. PMID: 11148810. [PubMed: 11148810] [CrossRef]

- 37.

- Hong S, Ahn H, Ha SJ, et al. Early glaucoma detection using the Humphrey Matrix Perimeter, GDx VCC, Stratus OCT, and retinal nerve fiber layer photography. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.021. PMID: 17270671. [PubMed: 17270671] [CrossRef]

- 38.

- Ivers RQ, Optom B, Macaskill P, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of tests to detect eye disease in an older population. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(5):968–75. PMID: 11320029. [PubMed: 11320029]

- 39.

- Jones L, Garway-Heath DF, Azuara-Blanco A, et al. Are patient self-reported outcome measures sensitive enough to be used as end points in clinical trials?: Evidence from the United Kingdom Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(5):682–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.09.034. PMID: 30273622. [PubMed: 30273622] [CrossRef]

- 40.

- Kahook MY, Serle JB, Mah FS, et al. Long-term safety and ocular hypotensive efficacy evaluation of netarsudil ophthalmic solution: rho kinase elevated IOP treatment trial (ROCKET-2). Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;200:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.003. PMID: 30653957. [PubMed: 30653957] [CrossRef]

- 41.

- Kamal D, Garway-Heath D, Ruben S, et al. Results of the betaxolol versus placebo treatment trial in ocular hypertension. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241(3):196–203. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0614-4. PMID: 12644943. [PubMed: 12644943] [CrossRef]

- 42.

- Karvonen E, Stoor K, Luodonpaa M, et al. Diagnostic performance of modern imaging instruments in glaucoma screening. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(10):1399–405. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314795. PMID: 31949097. [PubMed: 31949097] [CrossRef]

- 43.

- Kass MA, Gordon MO, Hoff MR, et al. Topical timolol administration reduces the incidence of glaucomatous damage in ocular hypertensive individuals. A randomized, double-masked, long-term clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(11):1590–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020668025. PMID: 2818278. [PubMed: 2818278] [CrossRef]

- 44.

- Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701–13. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. PMID: 12049574. [PubMed: 12049574] [CrossRef]

- 45.

- Katz J, Tielsch JM, Quigley HA, et al. Automated suprathreshold screening for glaucoma: the Baltimore Eye Survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(12):3271–7. PMID: 8225862. [PubMed: 8225862]

- 46.

- Kaushik S, Kataria P, Jain V, et al. Evaluation of macular ganglion cell analysis compared to retinal nerve fiber layer thickness for preperimetric glaucoma diagnosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(4):511–6. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1039_17. PMID: 29582810. [PMC free article: PMC5892052] [PubMed: 29582810] [CrossRef]

- 47.

- Kaushik S, Singh Pandav S, Ichhpujani P, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer measurement and diagnostic capability of spectral-domain versus time-domain optical coherence tomography. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(5):566–72. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2011.6289. PMID: 21279977. [PubMed: 21279977] [CrossRef]

- 48.

- Khouri AS, Serle JB, Bacharach J, et al. Once-daily netarsudil versus twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated intraocular pressure: the randomized phase 3 ROCKET-4 study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;204:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.002. PMID: 30862500. [PubMed: 30862500] [CrossRef]

- 49.

- Kiddee W, Tantisarasart T, Wangsupadilok B. Performance of optical coherence tomography for distinguishing between normal eyes, glaucoma suspect and glaucomatous eyes. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(6):689–95. PMID: 23951826. [PubMed: 23951826]

- 50.

- Kim SY, Park HY, Park CK. The effects of peripapillary atrophy on the diagnostic ability of stratus and cirrus OCT in the analysis of optic nerve head parameters and disc size. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(8):4475–84. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9682. PMID: 22618588. [PubMed: 22618588] [CrossRef]

- 51.

- Koh V, Tham YC, Cheung CY, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness for glaucoma detection in a population-based study: comparison with optic nerve head imaging parameters. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199134. PMID: 29944673. [PMC free article: PMC6019751] [PubMed: 29944673] [CrossRef]

- 52.

- Kozobolis VP, Detorakis ET, Tsilimbaris M, et al. Crete, Greece glaucoma study. J Glaucoma. 2000;9(2):143–9. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200004000-00003. PMID: 10782623. [PubMed: 10782623] [CrossRef]

- 53.

- Lai JS, Chua JK, Tham CC, et al. Five-year follow up of selective laser trabeculoplasty in Chinese eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;32(4):368–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00839.x. PMID: 15281969. [PubMed: 15281969] [CrossRef]

- 54.

- Lee KM, Lee EJ, Kim TW, et al. Comparison of the abilities of SD-OCT and SS-OCT in evaluating the thickness of the macular inner retinal layer for glaucoma diagnosis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147964. PMID: 26812064. [PMC free article: PMC4727815] [PubMed: 26812064] [CrossRef]

- 55.

- Lee WJ, Na KI, Kim YK, et al. Diagnostic ability of wide-field retinal nerve fiber layer maps using swept-source optical coherence tomography for detection of preperimetric and early perimetric glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(6):577–85. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000662. PMID: 28368998. [PubMed: 28368998] [CrossRef]

- 56.

- Lee WJ, Oh S, Kim YK, et al. Comparison of glaucoma-diagnostic ability between wide-field swept-source OCT retinal nerve fiber layer maps and spectral-domain OCT. Eye. 2018;32(9):1483–92. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0104-5. PMID: 29789659. [PMC free article: PMC6137103] [PubMed: 29789659] [CrossRef]

- 57.

- Leibowitz HM, Krueger DE, Maunder LR, et al. The Framingham Eye Study monograph: an ophthalmological and epidemiological study of cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, and visual acuity in a general population of 2631 adults, 1973-1975. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24(Suppl):335–610. PMID: 7444756. [PubMed: 7444756]

- 58.

- Liu S, Lam S, Weinreb RN, et al. Comparison of standard automated perimetry, frequency-doubling technology perimetry, and short-wavelength automated perimetry for detection of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(10):7325–31. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7795. PMID: 21810975. [PubMed: 21810975] [CrossRef]

- 59.

- Maa AY, Evans C, DeLaune WR, et al. A novel tele-eye protocol for ocular disease detection and access to eye care services. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(4):318–23. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0185. PMID: 24527668. [PubMed: 24527668] [CrossRef]

- 60.

- Maa AY, McCord S, Lu X, et al. The impact of OCT on diagnostic accuracy of the technology-based eye care services protocol: Part II of the Technology-Based Eye Care Services Compare Trial. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4):544–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.025. PMID: 31791664. [PubMed: 31791664] [CrossRef]

- 61.

- Maa AY, Medert CM, Lu X, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of technology-based eye care services: The Technology-Based Eye Care Services Compare Trial Part I. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.07.026. PMID: 31522900. [PubMed: 31522900] [CrossRef]

- 62.

- Marraffa M, Marchini G, Albertini R, et al. Comparison of different screening methods for the detection of visual field defects in early glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13(1–2):43–5. doi: 10.1007/bf02028636. PMID: 2744954. [PubMed: 2744954] [CrossRef]

- 63.

- Medeiros FA, Martin KR, Peace J, et al. Comparison of latanoprostene bunod 0.024% and timolol maleate 0.5% in open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: the LUNAR Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;168:250–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.05.012. PMID: 27210275. [PubMed: 27210275] [CrossRef]

- 64.

- Miglior S. Results of the European Glaucoma Prevention Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(3):366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.030. PMID: 15745761. [PubMed: 15745761] [CrossRef]

- 65.

- Miglior S, Zeyen T, Pfeiffer N, et al. The European glaucoma prevention study design and baseline description of the participants. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(9):1612–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01167-3. PMID: 12208707. [PubMed: 12208707] [CrossRef]

- 66.

- Morejon A, Mayo-Iscar A, Martin R, et al. Development of a new algorithm based on FDT Matrix perimetry and SD-OCT to improve early glaucoma detection in primary care. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:33–42. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S177581. PMID: 30643378. [PMC free article: PMC6311325] [PubMed: 30643378] [CrossRef]

- 67.

- Mundorf TK, Zimmerman TJ, Nardin GF, et al. Automated perimetry, tonometry, and questionnaire in glaucoma screening. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108(5):505–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90425-x. PMID: 2683793. [PubMed: 2683793] [CrossRef]

- 68.

- Nagar M, Luhishi E, Shah N. Intraocular pressure control and fluctuation: the effect of treatment with selective laser trabeculoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(4):497–501. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.148510. PMID: 19106150. [PubMed: 19106150] [CrossRef]

- 69.

- Nagar M, Ogunyomade A, O’Brart DP, et al. A randomised, prospective study comparing selective laser trabeculoplasty with latanoprost for the control of intraocular pressure in ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(11):1413–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.052795. PMID: 16234442. [PMC free article: PMC1772946] [PubMed: 16234442] [CrossRef]

- 70.

- Park HY, Park CK. Structure-function relationship and diagnostic value of RNFL area Index compared with circumpapillary RNFL thickness by spectral-domain OCT. J Glaucoma. 2013;22(2):88–97. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318231202f. PMID: 23232911. [PubMed: 23232911] [CrossRef]

- 71.

- Pazos M, Dyrda AA, Biarnes M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of spectralis SD OCT automated macular layers segmentation to discriminate normal from early glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(8):1218–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.03.044. PMID: 28461015. [PubMed: 28461015] [CrossRef]

- 72.

- Radius RL. Use of betaxolol in the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101(6):898–900. PMID: 6860201. [PubMed: 6860201]

- 73.

- Rao HL, Yadav RK, Addepalli UK, et al. Comparing spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and standard automated perimetry to diagnose glaucomatous optic neuropathy. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(5):e69–74. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000048. PMID: 25144210. [PubMed: 25144210] [CrossRef]

- 74.

- Ravalico G, Salvetat L, Toffoli G, et al. Ocular hypertension: a follow-up study in treated and untreated patients. New Trends in Ophthalmology. 1994;9(2):97–101.

- 75.

- Sall K. The efficacy and safety of brinzolamide 1% ophthalmic suspension (Azopt) as a primary therapy in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Brinzolamide Primary Therapy Study Group. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44 Suppl 2:S155–62. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00107-1. PMID: 10665518. [PubMed: 10665518] [CrossRef]

- 76.

- Sarigul Sezenoz A, Gur Gungor S, Akman A, et al. The diagnostic ability of ganglion cell complex thickness-to-total retinal thickness ratio in glaucoma in a caucasian population. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2020;50(1):26–30. doi: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2019.19577. PMID: 32167260. [PMC free article: PMC7086093] [PubMed: 32167260] [CrossRef]

- 77.

- Schulzer M, Drance SM, Douglas GR. A comparison of treated and untreated glaucoma suspects. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(3):301–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32296-6. PMID: 2023749. [PubMed: 2023749] [CrossRef]

- 78.

- Schwartz B, Lavin P, Takamoto T, et al. Decrease of optic disc cupping and pallor of ocular hypertensives with timolol therapy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 1995 (215):5–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1995.tb00588.x. PMID: 8846250. [PubMed: 8846250] [CrossRef]

- 79.

- Schweitzer C, Korobelnik JF, Le Goff M, et al. Diagnostic performance of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness for detection of glaucoma in an elderly population: the ALIENOR Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):5882–91. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20104. PMID: 27802518. [PubMed: 27802518] [CrossRef]

- 80.

- Serle JB, Katz LJ, McLaurin E, et al. Two phase 3 clinical trials comparing the safety and efficacy of netarsudil to timolol in patients with elevated intraocular pressure: rho kinase elevated IOP treatment trial 1 and 2 (ROCKET-1 and ROCKET-2). Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;186:116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.11.019. PMID: 29199013. [PubMed: 29199013] [CrossRef]

- 81.

- Soh ZD, Chee ML, Thakur S, et al. Asian-specific vertical cup-to-disc ratio cut-off for glaucoma screening: an evidence-based recommendation from a multi-ethnic Asian population. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;48(9):1210–8. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13836. PMID: 32734654. [PubMed: 32734654] [CrossRef]

- 82.

- Sung KR, Kim DY, Park SB, et al. Comparison of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by Cirrus HD and Stratus optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(7):1264–70, 70.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.045. PMID: 19427696. [PubMed: 19427696] [CrossRef]

- 83.

- Swamy B, Cumming RG, Ivers R, et al. Vision screening for frail older people: a randomised trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(6):736–41. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.134650. PMID: 18614568. [PubMed: 18614568] [CrossRef]

- 84.

- Tielsch JM, Katz J, Singh K, et al. A population-based evaluation of glaucoma screening: the Baltimore Eye Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(10):1102–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116013. PMID: 1746520. [PubMed: 1746520] [CrossRef]

- 85.

- Toris CB, Camras CB, Yablonski ME. Acute versus chronic effects of brimonidine on aqueous humor dynamics in ocular hypertensive patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(1):8–14. PMID: 10482088. [PubMed: 10482088]

- 86.

- Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1439–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.025. PMID: 15288969. [PubMed: 15288969] [CrossRef]

- 87.

- Vernon SA, Henry DJ, Cater L, et al. Screening for glaucoma in the community by non-ophthalmologically trained staff using semi automated equipment. Eye. 1990;4(Pt 1):89–97. PMID: 2182352. [PubMed: 2182352]

- 88.

- Vidas S, Popovic-Suic S, Novak Laus K, et al. Analysis of ganglion cell complex and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in glaucoma diagnosis. Acta Clinica Croatica. 2017;56(3):382–90. doi: 10.20471/acc.2017.56.03.04. PMID: 29479903. [PubMed: 29479903] [CrossRef]

- 89.

- Virgili G, Michelessi M, Cook J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of optical coherence tomography for diagnosing glaucoma: secondary analyses of the GATE study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102(5):604–10. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310642. PMID: 28855198. [PubMed: 28855198] [CrossRef]

- 90.

- Wahl J, Barleon L, Morfeld P, et al. The Evonik-Mainz Eye Care-Study (EMECS): development of an expert system for glaucoma risk detection in a working population. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0158824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158824. PMID: 27479301. [PMC free article: PMC4968826] [PubMed: 27479301] [CrossRef]

- 91.

- Weinreb RN, Liebmann JM, Martin KR, et al. Latanoprostene bunod 0.024% in subjects with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: pooled phase 3 study findings. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(1):7–15. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0000000000000831. PMID: 29194198. [PMC free article: PMC7654727] [PubMed: 29194198] [CrossRef]

- 92.

- Weinreb RN, Ong T, Scassellati Sforzolini B, et al. A randomised, controlled comparison of latanoprostene bunod and latanoprost 0.005% in the treatment of ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma: the VOYAGER study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(6):738–45. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305908. PMID: 25488946. [PMC free article: PMC4453588] [PubMed: 25488946] [CrossRef]

- 93.

- Weinreb RN, Scassellati Sforzolini B, Vittitow J, et al. Latanoprostene bunod 0.024% versus timolol maleate 0.5% in subjects with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: the APOLLO Study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):965–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.019. PMID: 26875002. [PubMed: 26875002] [CrossRef]

- 94.

- Wilkerson M, Cyrlin M, Lippa EA, et al. Four-week safety and efficacy study of dorzolamide, a novel, active topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(10):1343–50. PMID: 8216014. [PubMed: 8216014]

- 95.

- Wishart PK, Batterbury M. Ocular hypertension: correlation of anterior chamber angle width and risk of progression to glaucoma. Eye (Lond). 1992;6 ( Pt 3):248–56. doi: 10.1038/eye.1992.48. PMID: 1446756. [PubMed: 1446756] [CrossRef]

- 96.

- Xu X, Xiao H, Guo X, et al. Diagnostic ability of macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness in glaucoma suspects. Medicine. 2017;96(51):e9182. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009182. PMID: 29390457. [PMC free article: PMC5758159] [PubMed: 29390457] [CrossRef]

Appendix A5. Excluded Studies

- 1.

- Abdel-Hamid L. Glaucoma detection from retinal images using statistical and textural wavelet features. J Digit Imaging. 2020;33(1):151–8. doi: 10.1007/s10278-019-00189-0. PMID: 30756264. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC7064658] [PubMed: 30756264] [CrossRef]

- 2.

- Abrams LS, Scott IU, Spaeth GL, et al. Agreement among optometrists, ophthalmologists, and residents in evaluating the optic disc for glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(10):1662–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31118-3. PMID: 7936564. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 7936564] [CrossRef]

- 3.

- Acharya UR, Bhat S, Koh JEW, et al. A novel algorithm to detect glaucoma risk using texton and local configuration pattern features extracted from fundus images. Comput Biol Med. 2017;88:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2017.06.022. PMID: 28700902. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 28700902] [CrossRef]

- 4.

- Acharya UR, Dua S, Du X, et al. Automated diagnosis of glaucoma using texture and higher order spectra features. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2011;15(3):449–55. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2011.2119322. PMID: 21349793. Excluded for results not usable or not fully reported. [PubMed: 21349793] [CrossRef]

- 5.

- Acharya UR, Mookiah MR, Koh JE, et al. Automated screening system for retinal health using bi-dimensional empirical mode decomposition and integrated index. Comput Biol Med. 2016;75:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.04.015. PMID: 27253617. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 27253617] [CrossRef]

- 6.

- AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 11. Risk factors for failure of trabeculectomy and argon laser trabeculoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(4):481–98. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01658-6. PMID: 12383805. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 12383805] [CrossRef]

- 7.

- Ahmed R, Petrany S, Fry R, et al. Screening diabetic and hypertensive patients for ocular pathology using telemedicine technology in rural West Virginia: a retrospective chart review. W V Med J. 2013;109(1):6–10. PMID: 23413540. Excluded for results not usable or not fully reported. [PubMed: 23413540]

- 8.

- Ahmed S, Khan Z, Si F, et al. Correction: summary of glaucoma diagnostic testing accuracy: an evidence-based meta-analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(3):231. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2643wc1. PMID: 28179974. Excluded for not a study. [PMC free article: PMC5289146] [PubMed: 28179974] [CrossRef]

- 9.

- Ahmed S, Khan Z, Si F, et al. Summary of glaucoma diagnostic testing accuracy: an evidence-based meta-analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(9):641–9. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2643w. PMID: 27540437. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PMC free article: PMC4974833] [PubMed: 27540437] [CrossRef]

- 10.

- Ahn JM, Kim S, Ahn KS, et al. A deep learning model for the detection of both advanced and early glaucoma using fundus photography. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207982. PMID: 30481205. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC6258525] [PubMed: 30481205] [CrossRef]

- 11.

- Aihara M, Lu F, Kawata H, et al. Omidenepag isopropyl versus latanoprost in primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension: the Phase 3 AYAME Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;220:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.06.003. PMID: 32533949. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 32533949] [CrossRef]

- 12.

- Aihara M, Shirato S, Sakata R. Incidence of deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus after switching from latanoprost to bimatoprost. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55(6):600–4. doi: 10.1007/s10384-011-0075-6. PMID: 21953485. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 21953485] [CrossRef]

- 13.

- Airaksinen PJ, Drance SM, Douglas GR, et al. Diffuse and localized nerve fiber loss in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98(5):566–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90242-3. PMID: 6496612. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 6496612] [CrossRef]

- 14.

- Akashi A, Kanamori A, Nakamura M, et al. Comparative assessment for the ability of Cirrus, RTVue, and 3D-OCT to diagnose glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(7):4478–84. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11268. PMID: 23737470. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 23737470] [CrossRef]

- 15.

- Al-Akhras M, Barakat A, Alawairdhi M, et al. Using soft computing techniques to diagnose glaucoma disease. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(1):109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.09.005. PMID: 31668615. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 31668615] [CrossRef]

- 16.

- Al-Aswad LA, Kapoor R, Chu CK, et al. Evaluation of a deep learning system for identifying glaucomatous optic neuropathy based on color fundus photographs. J Glaucoma. 2019;28(12):1029–34. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001319. PMID: 31233461. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 31233461] [CrossRef]

- 17.

- Alencar LM, Zangwill LM, Weinreb RN, et al. Agreement for detecting glaucoma progression with the GDx guided progression analysis, automated perimetry, and optic disc photography. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):462–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.012. PMID: 20036010. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PMC free article: PMC2830299] [PubMed: 20036010] [CrossRef]

- 18.

- Alexander DW, Berson FG, Epstein DL. A clinical trial of timolol and epinephrine in the treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(2):247–51. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33205-7. PMID: 3050678. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 3050678] [CrossRef]

- 19.

- Allaire C, Dietrich A, Allmeier H, et al. Latanoprost 0.005% test formulation is as effective as Xalatan in patients with ocular hypertension and primary open-angle glaucoma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012;22(1):19–27. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000041. PMID: 22167539. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 22167539] [CrossRef]

- 20.

- Alm A, Schoenfelder J, McDermott J. A 5-year, multicenter, open-label, safety study of adjunctive latanoprost therapy for glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(7):957–65. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.7.957. PMID: 15249358. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 15249358] [CrossRef]

- 21.

- Alnawaiseh M, Lahme L, Muller V, et al. Correlation of flow density, as measured using optical coherence tomography angiography, with structural and functional parameters in glaucoma patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(3):589–97. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3865-9. PMID: 29332249. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 29332249] [CrossRef]

- 22.

- Aloudat M, Faezipour M, El-Sayed A. Automated vision-based high intraocular pressure detection using frontal eye images. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2019;7:3800113. doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.2019.2915534. PMID: 31281740. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC6537927] [PubMed: 31281740] [CrossRef]

- 23.

- Altangerel U, Spaeth GL, Steinmann WC. Assessment of function related to vision (AFREV). Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13(1):67–80. doi: 10.1080/09286580500428500. PMID: 16510349. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PubMed: 16510349] [CrossRef]

- 24.

- An G, Omodaka K, Hashimoto K, et al. Glaucoma diagnosis with machine learning based on optical coherence tomography and color fundus images. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:4061313. doi: 10.1155/2019/4061313. PMID: 30911364. Excluded for wrong population. [PMC free article: PMC6397963] [PubMed: 30911364] [CrossRef]

- 25.

- An G, Omodaka K, Tsuda S, et al. Comparison of machine-learning classification models for glaucoma management. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:6874765. doi: 10.1155/2018/6874765. PMID: 30018755. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC6029465] [PubMed: 30018755] [CrossRef]

- 26.

- Ang GS, Fenwick EK, Constantinou M, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus topical medication as initial glaucoma treatment: the glaucoma initial treatment study randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(6):813–21. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313396. PMID: 31488427. Excluded for wrong population. [PubMed: 31488427] [CrossRef]

- 27.

- Angmo D, Bhartiya S, Mishra SK, et al. Comparative evaluation of time domain and spectral domain optical coherence tomography in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2014;6(2):185–91. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v6i2.11692. PMID: 25680249. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 25680249] [CrossRef]

- 28.

- Annoh R, Loo CY, Hogan B, et al. Accuracy of detection of patients with narrow angles by community optometrists in Scotland. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2019;39(2):104–12. doi: 10.1111/opo.12601. PMID: 30600544. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 30600544] [CrossRef]

- 29.

- Anton A, Andrada MT, Mujica V, et al. Prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a Spanish population: the Segovia study. J Glaucoma. 2004;13(5):371–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000133385.74502.29. PMID: 15354074. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PubMed: 15354074] [CrossRef]

- 30.

- Anton A, Fallon M, Cots F, et al. Cost and detection rate of glaucoma screening with imaging devices in a primary care center. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:337–46. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S120398. PMID: 28243057. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PMC free article: PMC5317344] [PubMed: 28243057] [CrossRef]

- 31.

- Antón A, Maquet JA, Mayo A, et al. Value of logistic discriminant analysis for interpreting initial visual field defects. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(3):525–31. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30280-2. PMID: 9082284. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 9082284] [CrossRef]

- 32.

- Aptel F, Cucherat M, Denis P. Efficacy and tolerability of prostaglandin analogs: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(8):667–73. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181666557. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 19092464] [CrossRef]

- 33.

- Ara M, Ferreras A, Pajarin AB, et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of retinal nerve fiber layer parameters measured by scanning laser polarimetry with enhanced corneal compensation in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:729392. doi: 10.1155/2015/729392. PMID: 26185762. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC4491554] [PubMed: 26185762] [CrossRef]

- 34.

- Aref AA, Sayyad FE, Mwanza JC, et al. Diagnostic specificities of retinal nerve fiber layer, optic nerve head, and macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer measurements in myopic eyes. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(8):487–93. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31827b155b. PMID: 23221911. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC3986352] [PubMed: 23221911] [CrossRef]

- 35.

- Arifoglu HB, Simavli H, Midillioglu I, et al. Comparison of ganglion cell and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in pigment dispersion syndrome, pigmentary glaucoma, and healthy subjects with spectral-domain OCT. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017;32(2):204–9. PMID: 26291741. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 26291741]

- 36.

- Arora S, Rudnisky CJ, Damji KF. Improved access and cycle time with an “in-house” patient-centered teleglaucoma program versus traditional in-person assessment. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(5):439–45. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0241. PMID: 24568152. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PubMed: 24568152] [CrossRef]

- 37.

- Asano S, Asaoka R, Murata H, et al. Predicting the central 10 degrees visual field in glaucoma by applying a deep learning algorithm to optical coherence tomography images. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2214. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79494-6. PMID: 33500462. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PMC free article: PMC7838164] [PubMed: 33500462] [CrossRef]

- 38.

- Asaoka R, Hirasawa K, Iwase A, et al. Validating the usefulness of the “random forests” classifier to diagnose early glaucoma with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;174:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.11.001. PMID: 27836484. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 27836484] [CrossRef]

- 39.

- Asaoka R, Iwase A, Hirasawa K, et al. Identifying “preperimetric” glaucoma in standard automated perimetry visual fields. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(12):7814–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15120. PMID: 25342615. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 25342615] [CrossRef]

- 40.

- Asaoka R, Murata H, Hirasawa K, et al. Using deep learning and transfer learning to accurately diagnose early-onset glaucoma from macular optical coherence tomography images. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;198:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.10.007. PMID: 30316669. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 30316669] [CrossRef]

- 41.

- Asaoka R, Murata H, Iwase A, et al. Detecting preperimetric glaucoma with standard automated perimetry using a deep learning classifier. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(9):1974–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.05.029. PMID: 27395766. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 27395766] [CrossRef]

- 42.

- Aspberg J, Heijl A, Johannesson G, et al. Intraocular pressure lowering effect of latanoprost as first-line treatment for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(11):976–80. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001055. PMID: 30113517. Excluded for results not usable or not fully reported. [PubMed: 30113517] [CrossRef]

- 43.

- Ayaki M, Tsuneyoshi Y, Yuki K, et al. Latanoprost could exacerbate the progression of presbyopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0211631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211631. PMID: 30703139. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC6355011] [PubMed: 30703139] [CrossRef]

- 44.

- Ayala M, Chen E. Long-term outcomes of selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) treatment. Open Ophthalmol J. 2011;5:32–4. doi: 10.2174/1874364101105010032. PMID: 21643427. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PMC free article: PMC3104562] [PubMed: 21643427] [CrossRef]

- 45.

- Aydogan T, Akcay BIS, Kardes E, et al. Evaluation of spectral domain optical coherence tomography parameters in ocular hypertension, preperimetric, and early glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(11):1143–50. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_157_17. PMID: 29133640. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5700582] [PubMed: 29133640] [CrossRef]

- 46.

- Azuma I, Masuda K, Kitazawa Y, et al. Double-masked comparative study of UF-021 and timolol ophthalmic solutions in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1993;37(4):514–25. PMID: 8145398. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 8145398]

- 47.

- Bacharach J, Dubiner HB, Levy B, et al. Double-masked, randomized, dose-response study of AR-13324 versus latanoprost in patients with elevated intraocular pressure. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(2):302–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.08.022. PMID: 25270273. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 25270273] [CrossRef]

- 48.

- Badala F, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Raoof DA, et al. Optic disk and nerve fiber layer imaging to detect glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(5):724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.010. PMID: 17868631. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC2098694] [PubMed: 17868631] [CrossRef]

- 49.

- Bajwa MN, Malik MI, Siddiqui SA, et al. Two-stage framework for optic disc localization and glaucoma classification in retinal fundus images using deep learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0842-8. PMID: 31315618. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC6637616] [PubMed: 31315618] [CrossRef]

- 50.

- Balasubramanian K, Ananthamoorthy NP. Analysis of hybrid statistical textural and intensity features to discriminate retinal abnormalities through classifiers. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2019;233(5):506–14. doi: 10.1177/0954411919835856. PMID: 30894077. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 30894077] [CrossRef]

- 51.

- Bambo MP, Cameo B, Hernandez R, et al. Diagnostic ability of inner macular layers to discriminate early glaucomatous eyes using vertical and horizontal B-scan posterior pole protocols. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198397. PMID: 29879152. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5991695] [PubMed: 29879152] [CrossRef]

- 52.

- Bambo MP, Fuentemilla E, Cameo B, et al. Diagnostic capability of a linear discriminant function applied to a novel Spectralis OCT glaucoma-detection protocol. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-1322-8. PMID: 31996159. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC6988215] [PubMed: 31996159] [CrossRef]

- 53.

- Bamdad S, Beigi V, Sedaghat MR. Sensitivity and specificity of Swedish interactive threshold algorithm and standard full threshold perimetry in primary open-angle glaucoma. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 2017;6(4):125–9. PMID: 29560366. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5847307] [PubMed: 29560366]

- 54.

- Baniasadi N, Wang M, Wang H, et al. Ametropia, retinal anatomy, and OCT abnormality patterns in glaucoma. 2. Impacts of optic nerve head parameters. J Biomed Opt. 2017;22(12):1–9. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.12.121714. PMID: 29256238. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5745646] [PubMed: 29256238] [CrossRef]

- 55.

- Barella KA, Costa VP, Goncalves Vidotti V, et al. Glaucoma diagnostic accuracy of machine learning classifiers using retinal nerve fiber layer and optic nerve data from SD-OCT. J Ophthalmol. 2013;2013:789129. doi: 10.1155/2013/789129. PMID: 24369495. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC3863536] [PubMed: 24369495] [CrossRef]

- 56.

- Baril C, Vianna JR, Shuba LM, et al. Rates of glaucomatous visual field change after trabeculectomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(7):874–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308948. PMID: 27811280. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 27811280] [CrossRef]

- 57.

- Barnett EM, Fantin A, Wilson BS, et al. The incidence of retinal vein occlusion in the ocular hypertension treatment study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.022. PMID: 20031222. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC3077045] [PubMed: 20031222] [CrossRef]

- 58.

- Bartnik SE, Copeland SP, Aicken AJ, et al. Optometry-facilitated teleophthalmology: an audit of the first year in western Australia. Clin Exp Optom. 2018;101(5):700–3. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12658. PMID: 29444552. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PubMed: 29444552] [CrossRef]

- 59.

- Barua N, Sitaraman C, Goel S, et al. Comparison of diagnostic capability of macular ganglion cell complex and retinal nerve fiber layer among primary open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension, and normal population using fourier-domain optical coherence tomography and determining their functional correlation in Indian population. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(4):296–302. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.182941. PMID: 27221682. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC4901848] [PubMed: 27221682] [CrossRef]

- 60.

- Beato J, Pedrosa AC, Pinheiro-Costa J, et al. Long-term effect of anti-VEGF agents on intraocular pressure in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 2016;56(1):30–4. doi: 10.1159/000444395. PMID: 27046391. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 27046391] [CrossRef]

- 61.

- Begum VU, Addepalli UK, Senthil S, et al. Optic nerve head parameters of high-definition optical coherence tomography and Heidelberg retina tomogram in perimetric and preperimetric glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64(4):277–84. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.182938. PMID: 27221679. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC4901845] [PubMed: 27221679] [CrossRef]

- 62.

- Begum VU, Addepalli UK, Yadav RK, et al. Ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness of high definition optical coherence tomography in perimetric and preperimetric glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(8):4768–75. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14598. PMID: 25015361. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 25015361] [CrossRef]

- 63.

- Belfort R, Jr., Paula JS, Lopes Silva MJ, et al. Fixed-combination bimatoprost/brimonidine/timolol in glaucoma: a randomized, masked, controlled, phase III study conducted in Brazil. Clin Ther. 2020;42(2):263–75. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.12.008. PMID: 32089329. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 32089329] [CrossRef]

- 64.

- Bell RW, O’Brien C. Accuracy of referral to a glaucoma clinic. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1997;17(1):7–11. PMID: 9135806. Excluded for results not usable or not fully reported. [PubMed: 9135806]

- 65.

- Bell RW, O’Brien C. The diagnostic outcome of new glaucoma referrals. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1997;17(1):3–6. PMID: 9135805. Excluded for results not usable or not fully reported. [PubMed: 9135805]

- 66.

- Bengtsson B. Findings associated with glaucomatous visual field defects. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1980;58(1):20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1980.tb04561.x. PMID: 7405563. Excluded for results not usable or not fully reported. [PubMed: 7405563] [CrossRef]

- 67.

- Bengtsson B, Andersson S, Heijl A. Performance of time-domain and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography for glaucoma screening. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(4):310–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01977.x. PMID: 20946342. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PMC free article: PMC3440591] [PubMed: 20946342] [CrossRef]

- 68.

- Bengtsson B, Heijl A. Lack of visual field improvement after initiation of intraocular pressure reducing treatment in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(13):5611–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19389. PMID: 27768797. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PMC free article: PMC5080937] [PubMed: 27768797] [CrossRef]

- 69.

- Benitez-del-Castillo J, Martinez A, Regi T. Diagnostic capability of scanning laser polarimetry with and without enhanced corneal compensation and optical coherence tomography. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(3):228–36. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.5586. PMID: 20872357. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 20872357] [CrossRef]

- 70.

- Bergeå B, Bodin L, Svedbergh B. Primary argon laser trabeculoplasty vs pilocarpine. II: Long-term effects on intraocular pressure and facility of outflow. Study design and additional therapy. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1994;72(2):145–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1994.tb05008.x. PMID: 8079617. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 8079617] [CrossRef]

- 71.

- Bergea B, Svedbergh B. Primary argon laser trabeculoplasty vs. pilocarpine. Short-term effects. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1992;70(4):454–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1992.tb02114.x. PMID: 1414289. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 1414289] [CrossRef]

- 72.

- Berry DP, Jr., Van Buskirk EM, Shields MB. Betaxolol and timolol. A comparison of efficacy and side effects. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(1):42–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030026028. PMID: 6367723. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 6367723] [CrossRef]

- 73.

- Berson FG, Cohen HB, Foerster RJ, et al. Levobunolol compared with timolol for the long-term control of elevated intraocular pressure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(3):379–82. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050030075025. PMID: 3883972. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 3883972] [CrossRef]

- 74.

- Bertuzzi F, Benatti E, Esempio G, et al. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements for glaucoma detection: GDx ECC versus spectral-domain OCT. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(4):232–9. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3182741afc. PMID: 23970337. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 23970337] [CrossRef]

- 75.

- Bhagat P, Sodimalla K, Paul C, et al. Efficacy and safety of benzalkonium chloride-free fixed-dose combination of latanoprost and timolol in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1241–52. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S64584. PMID: 25061271. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PMC free article: PMC4085316] [PubMed: 25061271] [CrossRef]

- 76.

- Billy A, David PE, Mahabir AK, et al. Utility of the tono-pen in measuring intraocular pressure in Trinidad: a cross-sectional study. West Indian Med J. 2015;64(4):367–71. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2014.125. PMID: 26624589. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PMC free article: PMC4909069] [PubMed: 26624589] [CrossRef]

- 77.

- Binibrahim IH, Bergstrom AK. The role of trabeculectomy in enhancing glaucoma patient’s quality of life. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(3):150–4. doi: 10.4103/ojo.OJO_61_2016. PMID: 29118488. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PMC free article: PMC5657155] [PubMed: 29118488] [CrossRef]

- 78.

- Bizios D, Heijl A, Bengtsson B. Integration and fusion of standard automated perimetry and optical coherence tomography data for improved automated glaucoma diagnostics. BMC Ophthalmol. 2011;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-11-20. PMID: 21816080. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC3167760] [PubMed: 21816080] [CrossRef]

- 79.

- Blumberg DM, Vaswani R, Nong E, et al. A comparative effectiveness analysis of visual field outcomes after projected glaucoma screening using SD-OCT in African American communities. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(6):3491–500. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14014. PMID: 24787570. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC4073998] [PubMed: 24787570] [CrossRef]

- 80.

- Blyth CP, Moriarty AP, McHugh JD. Diode laser trabeculoplasty versus argon laser trabeculoplasty in the control of primary open angle glaucoma. Lasers Med Sci. 1999;14(2):105–8. doi: 10.1007/s101030050030. PMID: 24519164. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 24519164] [CrossRef]

- 81.

- Boland MV, Gupta P, Ko F, et al. Evaluation of frequency-doubling technology perimetry as a means of screening for glaucoma and other eye diseases using The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(1):57–62. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4459. PMID: 26562502. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 26562502] [CrossRef]

- 82.

- Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, et al. Prevalence of glaucoma and intraocular pressure distribution in a defined population. The Egna-Neumarkt Study. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(2):209–15. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)92665-3. PMID: 9479277. Excluded for wrong population. [PubMed: 9479277] [CrossRef]

- 83.

- Boodhna T, Crabb DP. More frequent, more costly? Health economic modelling aspects of monitoring glaucoma patients in England. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):611. PMID: 27770792. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PMC free article: PMC5075403] [PubMed: 27770792]

- 84.

- Bouacheria M, Cherfa Y, Cherfa A, et al. Automatic glaucoma screening using optic nerve head measurements and random forest classifier on fundus images. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2020;43(4):1265–77. doi: 10.1007/s13246-020-00930-y. PMID: 32986219. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 32986219] [CrossRef]

- 85.

- Bowd C, Belghith A, Proudfoot JA, et al. Gradient-boosting classifiers combining vessel density and tissue thickness measurements for classifying early to moderate glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;217:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.03.024. PMID: 32222368. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC7492367] [PubMed: 32222368] [CrossRef]

- 86.

- Bowling B, Chen SD, Salmon JF. Outcomes of referrals by community optometrists to a hospital glaucoma service. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(9):1102–4. PMID: 16113358. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PMC free article: PMC1772809] [PubMed: 16113358]

- 87.

- Bozkurt B, Irkec M, Arslan U. Diagnostic accuracy of Heidelberg retina tomograph III classifications in a Turkish primary open-angle glaucoma population. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88(1):125–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01591.x. PMID: 19681791. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 19681791] [CrossRef]

- 88.

- Brancato R, Carassa R, Trabucchi G. Diode laser compared with argon laser for trabeculoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112(1):50–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76212-9. PMID: 1882922. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 1882922] [CrossRef]

- 89.

- Brandao LM, Ledolter AA, Schotzau A, et al. Comparison of two different OCT systems: retina layer segmentation and impact on structure-function analysis in glaucoma. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:8307639. doi: 10.1155/2016/8307639. PMID: 26966557. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC4757732] [PubMed: 26966557] [CrossRef]

- 90.

- Bruen R, Lesk MR, Harasymowycz P. Baseline factors predictive of SLT response: a prospective study. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:642869. doi: 10.1155/2012/642869. PMID: 22900148. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PMC free article: PMC3415103] [PubMed: 22900148] [CrossRef]

- 91.

- Brusini P, Salvetat ML, Zeppieri M, et al. Comparison between GDx VCC scanning laser polarimetry and Stratus OCT optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of chronic glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84(5):650–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00747.x. PMID: 16965496. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 16965496] [CrossRef]

- 92.

- Budenz DL, Barton K, Gedde SJ, et al. Five-year treatment outcomes in the Ahmed Baerveldt comparison study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(2):308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.08.043. PMID: 25439606. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PMC free article: PMC4306613] [PubMed: 25439606] [CrossRef]

- 93.

- Buller AJ. Results of a glaucoma shared care model using the enhanced glaucoma staging system and disc damage likelihood scale with a novel scoring scheme in New Zealand. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:57–63. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S285966. PMID: 33442229. Excluded for wrong population. [PMC free article: PMC7800710] [PubMed: 33442229] [CrossRef]

- 94.

- Burgansky-Eliash Z, Wollstein G, Bilonick RA, et al. Glaucoma detection with the Heidelberg retina tomograph 3. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(3):466–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.022. PMID: 17141321. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC1945822] [PubMed: 17141321] [CrossRef]

- 95.

- Burgansky-Eliash Z, Wollstein G, Patel A, et al. Glaucoma detection with matrix and standard achromatic perimetry. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(7):933–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.110437. PMID: 17215267. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC1955642] [PubMed: 17215267] [CrossRef]

- 96.

- Burr J, Azuara-Blanco A, Avenell A. Medical versus surgical interventions for open angle glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 (2). Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 15846712]

- 97.

- Burr J, AzuaraBlanco A, Avenell A, et al. Medical versus surgical interventions for open angle glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 (9). Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 22972069]

- 98.

- Burr JM, Mowatt G, Hernandez R, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for open angle glaucoma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(41):iii–iv, ix–x, 1–190. doi: 10.3310/hta11410. PMID: 17927922. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PubMed: 17927922] [CrossRef]

- 99.

- Bussel, II, Wollstein G, Schuman JS. OCT for glaucoma diagnosis, screening and detection of glaucoma progression. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98 Suppl 2:ii15–9. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304326. PMID: 24357497. Excluded for not a study. [PMC free article: PMC4208340] [PubMed: 24357497] [CrossRef]

- 100.

- Byles DB, Sherafat H, Diamond JP. Frequency doubling technology screening test in glaucoma detection. Iovs. 2000;41(452). Excluded for wrong publication type.

- 101.

- Caffery LJ, Taylor M, Gole G, et al. Models of care in tele-ophthalmology: a scoping review. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(2):106–22. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17742182. PMID: 29165005. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PubMed: 29165005] [CrossRef]

- 102.

- Calvo P, Ferreras A, Abadia B, et al. Assessment of the optic disc morphology using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:275654. doi: 10.1155/2014/275654. PMID: 25110668. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC4109590] [PubMed: 25110668] [CrossRef]

- 103.

- Cantor LB, Hoop J, Katz LJ, et al. Comparison of the clinical success and quality-of-life impact of brimonidine 0.2% and betaxolol 0.25 % suspension in patients with elevated intraocular pressure. Clin Ther. 2001;23(7):1032–9. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80089-8. PMID: 11519768. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 11519768] [CrossRef]

- 104.

- Carle CF, James AC, Kolic M, et al. Luminance and colour variant pupil perimetry in glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42(9):815–24. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12346. PMID: 24725214. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 24725214] [CrossRef]

- 105.

- Carle CF, James AC, Kolic M, et al. High-resolution multifocal pupillographic objective perimetry in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(1):604–10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5737. PMID: 20881285. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 20881285] [CrossRef]

- 106.

- Cazana IM, Bohringer D, Reinhard T, et al. A comparison of optic disc area measured by confocal scanning laser tomography versus Bruch’s membrane opening area measured using optical coherence tomography. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-01799-x. PMID: 33430821. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PMC free article: PMC7802149] [PubMed: 33430821] [CrossRef]

- 107.

- Cellini M, Toschi PG, Strobbe E, et al. Frequency doubling technology, optical coherence technology and pattern electroretinogram in ocular hypertension. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:33. PMID: 22853436. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC3444883] [PubMed: 22853436]

- 108.

- Cennamo G, Montorio D, Romano MR, et al. Structure-functional parameters in differentiating between patients with different degrees of glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(10):e884–e8. PMID: 27483418. Excluded for wrong population. [PubMed: 27483418]

- 109.

- Cennamo G, Montorio D, Velotti N, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in pre-perimetric open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255(9):1787–93. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3709-7. PMID: 28631244. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 28631244] [CrossRef]

- 110.

- Chabi A, Varma R, Tsai JC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of preservative-free tafluprost and timolol in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(6):1187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.11.008. PMID: 22310086. Excluded for wrong comparator. [PubMed: 22310086] [CrossRef]

- 111.

- Chaganti S, Nabar KP, Nelson KM, et al. Phenotype analysis of early risk factors from electronic medical records improves image-derived diagnostic classifiers for optic nerve pathology. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2017;10138:11. doi: 10.1117/12.2254618. PMID: 28736474. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5521270] [PubMed: 28736474] [CrossRef]

- 112.

- Chai C, Loon SC. Meta-analysis of viscocanalostomy versus trabeculectomy in uncontrolled glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2010;19(8):519–27. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181ca7694. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 20179632] [CrossRef]

- 113.

- Chakrabarty L, Joshi GD, Chakravarty A, et al. Automated detection of glaucoma from topographic features of the optic nerve head in color fundus photographs. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(7):590–7. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000354. PMID: 26580479. Excluded for wrong intervention. [PubMed: 26580479] [CrossRef]

- 114.

- Chakravarti T, Moghimi S, De Moraes CG, et al. Central-most visual field defects in early glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2020;02:02. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001747. PMID: 33273288. Excluded for wrong population. [PubMed: 33273288] [CrossRef]

- 115.

- Chandrasekaran S, Cumming RG, Rochtchina E, et al. Associations between elevated intraocular pressure and glaucoma, use of glaucoma medications, and 5-year incident cataract: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(3):417–24. PMID: 16458969. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 16458969]

- 116.

- Chandrasekaran S, Kass W, Thangamathesvaran L, et al. Tele-glaucoma vs clinical evaluation: the New Jersey Health Foundation Prospective Clinical Study. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(9):536–44. doi: 10.1177/1357633X19845273. PMID: 31138016. Excluded for wrong outcome. [PubMed: 31138016] [CrossRef]

- 117.

- Chang DS, Xu L, Boland MV, et al. Accuracy of pupil assessment for the detection of glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.04.012. PMID: 23809274. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PMC free article: PMC3818414] [PubMed: 23809274] [CrossRef]

- 118.

- Chang RT, Knight OJ, Feuer WJ, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of time-domain versus spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in diagnosing early to moderate glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(12):2294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.012. PMID: 19800694. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 19800694] [CrossRef]

- 119.

- Chaurasia S, Garg R, Beri S, et al. Sonographic assessment of optic disc cupping and its diagnostic performance in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2019;28(2):131–8. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001123. PMID: 30461554. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 30461554] [CrossRef]

- 120.

- Chen A, Liu L, Wang J, et al. Measuring glaucomatous focal perfusion loss in the peripapillary retina using OCT angiography. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4):484–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.041. PMID: 31899032. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC7093216] [PubMed: 31899032] [CrossRef]

- 121.

- Chen HY, Chang YC. Meta-analysis of stratus OCT glaucoma diagnostic accuracy. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91(9):1129–39. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000331. PMID: 25036543. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PubMed: 25036543] [CrossRef]

- 122.

- Chen HY, Chang YC, Wang IJ, et al. Comparison of glaucoma diagnoses using stratus and cirrus optical coherence tomography in different glaucoma types in a Chinese population. J Glaucoma. 2013;22(8):638–46. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3182594f42. PMID: 22595933. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 22595933] [CrossRef]

- 123.

- Chen HY, Huang ML, Tsai YY, et al. Comparing glaucomatous optic neuropathy in primary open angle and primary angle closure glaucoma eyes by scanning laser polarimetry-variable corneal compensation. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(2):105–10. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31814b9971. PMID: 18344755. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 18344755] [CrossRef]

- 124.

- Chen HY, Wang TH, Lee YM, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography and its correlation with visual field defects in early glaucoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(12):927–34. PMID: 16607450. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PubMed: 16607450]

- 125.

- Chen R, Yang K, Zheng Z, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of latanoprost monotherapy in patients with angle-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(3):e134–44. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000158. PMID: 25383466. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PubMed: 25383466] [CrossRef]

- 126.

- Chen TC, Hoguet A, Junk AK, et al. Spectral-domain OCT: helping the clinician diagnose glaucoma: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(11):1817–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.008. PMID: 30322450. Excluded for systematic review or meta-analysis used as a source document only to identify individual studies. [PubMed: 30322450] [CrossRef]

- 127.

- Chen X, Zhao Y. Diagnostic performance of isolated-check visual evoked potential versus retinal ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer analysis in early primary open-angle glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0472-9. PMID: 28532392. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5440894] [PubMed: 28532392] [CrossRef]

- 128.

- Chen XW, Zhao YX. Comparison of isolated-check visual evoked potential and standard automated perimetry in early glaucoma and high-risk ocular hypertension. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(4):599–604. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2017.04.16. PMID: 28503434. Excluded for wrong study design for key question. [PMC free article: PMC5406639] [PubMed: 28503434] [CrossRef]

- 129.