Context and Policy Issues

Psoriasis is an autoimmune and inflammatory disease with genetic predispositions that generally occurs before age 35.1 The development of the disease is driven by multiple pathways of immune mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-23 and IL-17 cytokines. Psoriasis affects about 3% of the population and is associated with systemic diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.1 Plaque psoriasis is the most common form of the disease, accounting for about 70% to 90% of all patients with psoriasis.1,2 It is characterized by itchy, red, scaly, raised lesions on the skin, especially on the scalp, elbows, knees, scalp, and back extensor extremities and trunk.1 Psoriasis significantly impairs patients’ quality of life.3

Most patients with plaque psoriasis have mild disease that is adequately managed with topical application of corticosteroids, emollients, vitamin D analogs, coal tar products, retinoids and calcineurin inhibitors, or phototherapy.1 Moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis symptoms are generally treated with systemic therapies.2,4 They have a significant negative impact on patient quality of life.1,2 and are associated with a considerable economic burden.4,5 Treatment options include conventional agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, and relatively newer biologic agents. Biologics approved for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis include of TNF-α inhibitors (e.g., as adalimumab and infliximab), IL-17 inhibitors (e.g., ixekizumab, and secukinumab) and IL-23 inhibitors (e.g., risankizumab).3,4,6–9 Unlike the non-specific conventional immunomodulators, biologic treatments for psoriasis are less likely to cause systematic adverse events because of their specificity for immune targets.3,10

Adalimumab was among the earlier biologic agents that received approval from Health Canada for the treatment of severe plaque psoriasis.11 Others with similar approved indications include infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, and secukinumab.11 The variety of biologic agents currently available for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriatic presents a challenge to clinicians in making choices that optimize patients’ outcomes. It also creates the need for decision-makers to determine suitable places in therapy for the available treatment options, using evidence-based information. In 2008, CADTH conducted a Common Drug Review (CDR) of adalimumab in patients with plaque psoriasis.12 However, that review12 did not cover the comparative effectiveness of adalimumab to other biologics for that indication.

The aim of this Rapid Response review is to compare and summarize evidence about the clinical effectiveness of adalimumab versus other biologic drugs indicated for the treatment of in adult patients with plaque psoriasis.

Research Question

What is the clinical effectiveness of adalimumab versus other biologic drugs in adult patients with plaque psoriasis?

Key Findings

Evidence from five systematic reviews (four with network meta-analysis and one with traditional meta-analysis) and one randomized controlled trial suggested that adalimumab was less effective than infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, and secukinumab in achieving skin clearance and improvements in health-related quality of life in patients diagnosed with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Apart from the randomized controlled trial comparing adalimumab to risankizumab, separate data from direct comparison were not available for effectiveness and safety. There was not enough evidence to draw a firm conclusion about the comparative safety of adalimumab versus the other biologics of interest.

Substantial overlap of primary studies across the systematic reviews showed that the pooled estimates from the separate reviews contain some data from the same primary studies. An assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies did not find issues that present significant uncertainty about the findings in four systematic reviews and the randomized controlled trial. The quality of one systematic review was limited due to inadequate reporting. However, the results from that study were consistent with the others. Thus, they did not appear likely to impact the overall evidence reported here. The consistency could be due to the overlap of the primary studies included in the systematic reviews.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted by an information specialist on key resources including PubMed, the Cochrane Library, the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, the websites of Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused internet search. The search strategy was comprised of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concepts were psoriasis and adalimumab and other biologics. Filters were applied to limit the retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, and meta analyses, and randomized controlled trials. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2010 and April 21, 2020.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2015. Systematic reviews (SRs) in which all relevant studies were captured in other more recent or more comprehensive systematic reviews were excluded. Primary studies retrieved by the search were excluded if they were captured in one or more included SRs.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included publications were critically appraised by one reviewer using the following tools as a guide: A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2)13 for SRs, the “Questionnaire to assess the relevance and credibility of a network meta-analysis”14 for network meta-analyses (NMAs), the Downs and Black checklist15 for the randomized controlled trial (RCT). Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, the strengths and limitations of each included publication were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

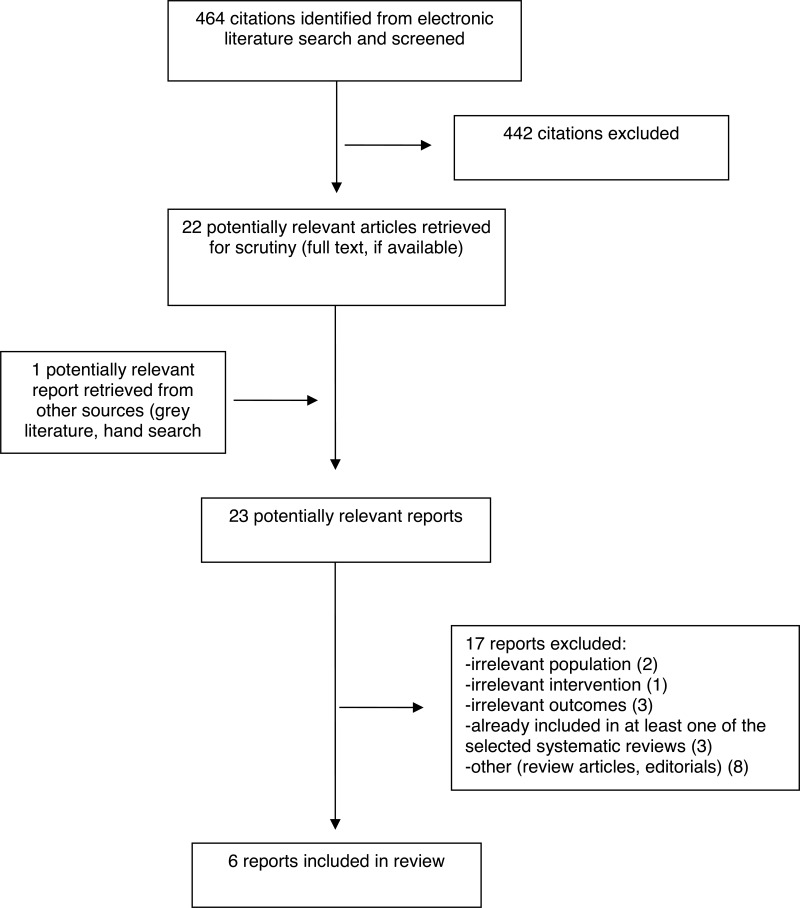

A total of 464 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 442 citations were excluded and 22 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. One potentially relevant publication was retrieved from the grey literature search for full-text review. Of 23 potentially relevant articles, 17 publications were excluded for various reasons, and six publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised five SRs,3,4,7–9 and one RCT.6

Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA16 flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Overall, the six studies3,4,6–9 included in this report assessed the effectiveness of 13 biologics in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. They were adalimumab, briakinumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, itolizumab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, secukinumab, tildrakizumab, and ustekinumab. However, only data and comparisons needed to answer the research question of this Rapid Response report will be discussed further. The citation matrix in Appendix 5 shows the degree of overlap of primary studies across the SRs.

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Five SRs3,4,7–9 and one RCT6 were included in this report. The SRs were published from 2015 to 2020 and their included studies were published from 2001 to 2019. Four SRs conducted NMA,3,4,7,8 whereas one performed a traditional meta-analysis.9 Details about the study arms of the RCTs included the SRs3,4,7–9 were not enough to determine the number of studies that directly compared adalimumab to any of the other biologics agents of interest to this report (i.e., infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab and secukinumab).

The SR by Warren et al.3 included 33 RCTs. They were identified by systematic literature review of databases, books and journals offered by the Medical Library at Health First (i.e., the OvidSP platform) for literature published from 1 January 1990 to 12 December 2018. Eighteen of the RCTs evaluated biologics agents of interest to this report and were included in NMA.3

Sawyer et al.4 included 98 publications covering 67 RCTs, including 17 trials that were involved in NMA. Of the 17 trials, nine RCTs investigated biologics agents of interest to this report. The studies were identified from a systematic search of multiple databases from 2000 to 31st August 2016.4

The SR by Xu et al.7 included 54 RCTs, including 27 trials that assessed biologics agents of interest to this report. They were identified by systematic search conducted in multiple databases from inception to 8th August 2018 and supplemented with manual searches of related bibliographies.

The SR by Jabbar-Lopez et al.8 was based on 45 articles presenting data from 41 RCT including 16 RCTs that evaluated the biologics of interest to this report. The studies were identified through a systematic literature search conducted in multiple databases from inception to 17th October, 2016.8

The SR by Nast et al.9 included 31 publications based on 25 RCTs, including nine RCTs that investigated biologics agents of interest to this report . The investigators conducted systematic literature searches of the OvidSP platform for relevant studies from inception to 5th January 2015.

The RCT by Reich et al.6 was published in 2019. It was randomized, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled trial conducted at 66 clinics. The RCT had two parts. In the first section (Part A), patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to either of the two treatment groups (risankizumab or adalimumab) for a 16-week double-blind treatment period. In the second phase (Part B), adalimumab intermediate responders were re-randomized 1:1 to continue receiving adalimumab or switch to risankizumab for weeks 16 to 44. It is worth noting that this RCT was one of four studies that were included a CADTH CDR published in June 2019.17

Country of Origin

Lead authors of the three SRs with NMA3,4,8 were from the United Kingdom and the authors other of another SR with NMA7 were from China. The SR with traditional MA was conducted by reviewers in Germany.9 The RCT6 was a global study with sites in Canada, seven European countries (Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Poland, Portugal, and Sweden), Mexico, Taiwan, and the United States of America.

Patient Population

Four SRs3,4,7,9 included RCTs involving adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. One other SR8 included RCTs that enrolled all people with psoriasis of any severity being treated primarily for their skin disease. However, the included studies of relevance to this report involved adult patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. There was not enough information in the SR by Warren et al.3 about the specific number of patients treated with the biologics of interest to provide in this Rapid Response report. For the remaining SRs by Sawyer et al.,4 Xu et al.,7 Jabbar-Lopez et al.8 and Nast et al.,9 the total number of patients per SR treated with biologics agents of interest to this report ranged from 2,447 to 9,530. Note that for NMAs, all included patients (not just those from trials relevant to this report) contribute to the indirect treatment comparisons. The RCT by Reich et al.6 involved a total of 605 adult patients (mean age 46 ± 13 years) with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis.

Interventions and Comparators

Overall, the six studies3,4,6–9 included in this report assessed the effectiveness of 13 biologics (adalimumab, briakinumab, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, itolizumab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, secukinumab, tildrakizumab, and ustekinumab) in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. However, only data and comparisons needed to answer the research question of this Rapid Response report will be discussed further. The treatment protocols of the biologics in the primary studies of the included SRs3,4,7–9 were not uniformly reported. In the included RCT by Reich et al.,6 patients were randomly assigned to receive 150 mg risankizumab at weeks 0 and 4 or 80 mg adalimumab at randomization, then 40 mg at weeks 1, 3, 5, and every other week after that during a 16-week double-blind treatment period (Part A). In Part B of the trial (weeks 16 to 44), patients who had intermediate responses to adalimumab were re-randomized to either continue 40 mg adalimumab or switch to 150 mg risankizumab. An intermediate response was defined as Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores ≥50 to PASI <90. Each treatment was administered subcutaneously.

Outcomes

Four of the included SRs3,4,7,9 and the RCT6 used the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores. The PASI is a validated measure widely used in clinical trials to assess symptomatic changes in thickness, scale, and erythema in psoriasis patients, usually performed following 12 weeks of therapy.10 Treatment success is determined by the percentage improvement in PASI score from baseline, with PASI 75, PASI 90, or PASI 100 denoting ≥ 75%, ≥ 90%, or 100% improvement, respectively.

Four of the included SRs3,7–9 and the RCT6 investigated Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) response rates. The DLQI is a well-established tool widely used to measure the quality of life related to skin disease in psoriasis trials.10 The DLQI scores range from 0 (not affected at all) to 3 (very much affected) for each of 10 questions, with a total scores range from 0 to 30, where lower scores mean better quality of life.

Three of the included SRs7–9 and the RCT6 reported Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) outcomes. The PGA is a 5- to 7-point scale ranging from “clear” to “very severe psoriasis,” which is used in trials for clinical assessment.10 Treatment success on PGA is generally defined as achieving clear or almost clear disease.10 These four included studies6–9 also reported safety outcomes, such as adverse events (AEs), serious (SAEs) and withdrawal (or discontinuation) due to adverse events (WDAEs).

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 3.

Included Systematic Reviews

The authors of each the included SRs3,4,7–9 provided well-defined study objectives and inclusion criteria that identified the population, interventions, comparators and outcomes of their respective research questions. One SR8 established the study protocol and registered with the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) before conducting the review. It was unclear if any of the remaining SRs3,4,7,9 established a protocol ahead of conducting the studies. Each SR was based on RCTs retrieved through a systematic literature search in multiple databases. The reporting of one SR3 was poor, with no information about many quality parameters such as methods for abstract screening, study selection and data extraction, characteristics of the included studies, the number of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion, and evaluation of the risk of bias of primary RCTs. In four of the SRs,4,7–9 the characteristics of the individual included studies were provided, and abstracts screening, study selection, and data extractions were performed in duplicate, resolving any disputes by consensus or through a third reviewer. The four SRs,4,7–9 assessed the risk of bias of included primary studies and considered the limitations in the individual studies in discussing the results of the reviews. Three SRs7–9 investigated publication bias, whereas two others3,4 did not. Two SRs8,9 assessed heterogeneity with one using visual inspection of the forest plots,8 while the other used the I2 test.9 Methodological limitations in the SRs included absence of information on the number and lists of excluded studies,3,4 and reasons for exclusion,3 lack of clarity on the method of abstract screening,3 study selection3 and data extraction,3,4 as well as inadequate information about the characteristic of the included studies3 and evaluation of the risk of bias in the primary RCTs.3 Other limitations were uncertainty about appropriate assessment of heterogeneity3,7 and publication bias.3,4

All the included SRs3,4,7–9 used appropriate methods for statistical analyses and reported results along with measures of uncertainty. All the NMAs used the more robust random effects models and there were no naïve comparisons. The NMAs in three SRs,3,4,7 were based on Bayesian analysis, whereas one SR8 used the frequentist approach for NMA. Although the reported study selection criteria indicated that the populations of RCTs included in the SRs.3,4,7–9 were applicable to the population of interest of this Rapid Response report, there was not enough information to assess the relevance of the setting for the included RCTs. Also, there was not enough information to evaluate if systematic differences in treatment effect modifiers existed across the different treatment comparisons in the networks. One SR7 did not receive any funding for the study and one SR8 was funded by the British Association of Dermatologists to inform the next update to the clinical guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis, and another SR was funded by the European Dermatology Forum to update of the European psoriasis guidelines. In all three SRs,7–9 no conflicts were reported that could potentially impact the conduct and reporting of the studies. Two SRs3,4 were funded by pharmaceutical companies, and all the authors were involved with the pharmaceutical industry in various capacities, such as areas advisory board member, consultant and/or speaker, employee, investigator, and shareholder. There was no apparent issue with the methodological quality of four SRs4,7–9 that presented a significant uncertainty about their findings. The quality of one SR3 was limited due inadequate reporting.

Included Primary Clinical Study

The included RCT6 was a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, active-comparator trial done at 66 sites in 11 countries, including Canada. Thus, the study design minimizes the risk of bias, and the multiple countries and sites suggest a good generalizability. The objectives of the study and patients’ characteristics were well-defined and the interventions (risankizumab and adalimumab) were described with details about doses, route of administration, and periods of follow-up. The investigators performed sample size calculations to determine that the study was adequately powered to identify clinically meaningful differences in treatment effects between the risankizumab and the adalimumab groups. The outcomes were measured with validated scales that are commonly used in clinical research, and the results were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. The primary analysis was based on the intention-to-treat population and estimates for the main findings were reported along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and P values. Patients enrolled in Part B of the RCT had achieved intermediate response to adalimumab during the first phase of the trial which lasted 16 weeks. Thus, the re-randomization of these patients to continue treatment with adalimumab or switch to receive risankizumab could have resulted in selection bias in favour of risankizumab. The number of missing data from each study arm was low (two or fewer patients missing per arm) and similar across groups for the entire study period. Missing efficacy data were handled using non-responder imputation for categorical variables and last observation carried forward for continuous variables. A per-protocol analysis produced consistent results with the intention-to-treat analyses, suggesting robustness of the findings. Adverse events were assessed and reported for the two arms of the study. However, the study duration was not enough for long-term safety and effectiveness. The article, which was the source of evidence from the RCT,6 for this report, did not provide information about patients’ adherence to the allocated treatment. However, a previous CADTH CDR17 that included this RCT6 and three others in assessing the effectiveness of risankizumab for psoriasis, reported that “adherence was generally high throughout each study and well balanced across treatment groups; it was therefore unlikely to create bias in favour of any treatment.” In general, the CDR process accesses a wider scope of information, including unpublished materials; however, the critical appraisal provided in this Rapid Response report is in agreement with the main appraisal points of that CDR report.17 The study was sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that contributed to study design and participated in data collection, data analysis and interpretation, as well as the writing, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Summary of Findings

Appendix 4 presents the main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

Clinical Effectiveness of adalimumab versus other biologic drugs in adult patients with plaque psoriasis

Five SRs3,4,7–9 and one RCT6 reported findings on the comparative effectiveness of adalimumab versus infliximab,3,4,7–9 ixekizumab,3,7,8 risankizumab,3,6 and secukinumab in adult patients diagnosed with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.3,4,7–9 Evidence of effectiveness was evaluated using PASI and PGA for skin clearance and DLQI for patients’ health-related quality of life. The statistical approaches used to handle data and the units of outcome reporting were different for each of the included SRs3,4,7–9 and RCT.6 However, all the included studies were consistent in showing that adalimumab was less effective than the comparator biologic agents for skin clearance and improvements in the quality of life for patients with moderate- to-severe psoriasis in the short-term (12 weeks),3,7 medium-term (16 to 24 weeks),7,9 extended follow-up of 40 to 60 weeks,4 or up to three years.8 It should be noted that in Part B of the included RCT,6 the re-randomization of patients from Part A who achieved intermediate response to adalimumab to either continue treatment with adalimumab or switch to risankizumab may have introduced selection bias in favour of risankizumab. That may explain the bigger differences in outcomes between the two drugs in Part B compared to Part A ().

Skin clearance

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

Four SRs3,7–9 and one RCT6 provided PASI findings. Warren et al.3 found that for PASI 75, the relative treatment effect was 0.63 (95% credible interval [CrI], 0.604, 0.662) for adalimumab and 0.85 (95 CrI, 0.825, 0.866), 0.80 (95 CrI, 0.752, 0.839), 0.76 (95 CrI, 0.740, 0.789), and 0.75 (95 CrI, 0.715, 0.793) for ixekizumab, risankizumab, secukinumab, and infliximab, respectively. The comparisons in the SRs by Sawyer et al.,4 Xu et al.,7 and Nast et al. showed a similar trend,9 which was repeated for PASI 90 and PASI 100 scores. In the RCT by Reich et al.,6 72% of patients treated with risankizumab achieved the co-primary endpoint at PASI 90 at the week-16 follow-up assessment compared with 47% of those who were treated with adalimumab. The difference was statistically significant with an adjusted absolute difference of 24.9% (95% CI, 17.5 to 32.4; p<0.0001). Risankizumab also showed superior PASI 75 and PASI 100 scores than adalimumab. The difference was statistically significant (p<0.0001) in all comparisons. Similar trends were observed at week 44 assessment among patients who had intermediate response (defined as PASI ≥50 to PASI <90) after 16 weeks of adalimumab treatment who were re-randomized to receive risankizumab or to continue treatment with adalimumab.

Physician’s global assessment

Three SRs6–8 reported skin clearance findings as evaluated with the PGA score of clear or nearly clear (0, 1). Jabbar-Lopez et al.8 compare the PGA (0, 1) of infliximab, ixekizumab and secukinumab to adalimumab and reported pairwise odds ratios (OR) of 4.08 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.69, 9.88), 2.86 (95% CI, 1.30, 6.27), and 0.98 (95% CI, 0.43, 2.26), respectively. Xu et al.7 found that the odds ratio (OR) for PGA was 11 (95% CrI, 6.2, 17) for adalimumab, 87 (95% CrI, 52, 140) for ixekizumab, and 40 (95% CrI, 9.1, 180) for and infliximab. Pooled risk ratios (RR) for PGA in the SR by Nast et al.9 were consistent with these findings showing that adalimumab was the least effective compared with infliximab and secukinumab for skin clearance, as indicated by the PGA (0, 1) score. In the RCT by Reich et al.,6 84% patients treated with risankizumab achieved PGA (0, 1) score compared with 60% patients given adalimumab. The difference was statistically significant with an adjusted absolute difference of 23.3% (95% CI, 16.6 to 30.1; p<0.0001).

Quality of Life

Four SRs3,7–9 and one RCT6 reported psoriasis-related quality of life outcomes as measured by the DLQI. Warren et al.3 found that the relative treatment effect of achieving scores of 0 or 1 (i.e., no effect on the patient’s life) was 0.18 (95% Cr, 0.101, 0.260) for adalimumab, 0.53 (95% Cr, 0.497, 0.567) for secukinumab, and 0.57 (95% Cr, 0.533, 0.612) for ixekizumab. DLQI scores of 0 or 1 results from Xu et al.,7 Jabbar-Lopez et al.,8 and Nast et al.9 were consistent with this finding in showing that treatment adalimumab was associated with a lower improvements in health-related quality of life for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis compared with infliximab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. In the RCT by Reich et al.,6 66% of patients treated with risankizumab achieved DLQI scores of 0 or 1 compared with 49% who were treated with adalimumab. The difference was statistically significant (p<0.0001); however, the adjusted absolute difference was not reported for this outcome.

Safety

Adverse event (AE) findings were reported by three SRs7–9 and one RCT.6 Xu et al.,7 assessed the occurrence of headache and infection, as well as AEs leading to withdrawal from treatment or discontinuation of study drug. They reported that infliximab and ixekizumab had a higher risk than placebo for the occurrence of headache, whereas adalimumab and ixekizumab had a higher risk than placebo for the occurrence of infection. The odds of withdrawal or discontinuation was also higher with ixekizumab versus placebo. The SR by Nast et al.9 found that the relative risk of AEs, serious AEs, and AEs leading to withdrawal or discontinuation of treatment drug was higher in infliximab versus placebo than adalimumab versus placebo. Two SRs7,9 did not report data comparing the safety of adalimumab to the other biologics of interest. Rather, they provided results of comparing each biologic to placebo. Thus, it was unclear if a significant difference in safety parameters existed between adalimumab and infliximab, ixekizumab, or secukinumab. Jabbar-Lopez et al.,8 reported that the odds of AEs leading to withdrawal was statistically significantly lower with adalimumab compared with infliximab or ixekizumab, but not statistically significantly different compared to secukinumab. Based on higher occurrence of AEs leading to discontinuation, they suggested that ixekizumab and infliximab had poorer tolerability than adalimumab and secukinumab, which were considered to have comparable tolerability.

In the RCT by Reich et al.,6 the frequencies of AEs were low for both risankizumab and adalimumab, and there were no statistically significant differences in AEs between the two study groups.

Limitations

Considerable overlap occurred in the primary studies that were included in the SRs.3,4,7–9 Thus, the pooled estimates from the separate reviews contain some of the same data. The citation matrix in Appendix 5 shows the degree of overlap of primary studies across the SRs.

Apart from one RCT6 comparing adalimumab directly to risankizumab, there was no other study identified that compared adalimumab directly to any of the biologic agents of interest to this report. Thus, the results from the five SRs3,4,7–9 were derived from indirect treatment comparisons, which require additional assumptions (e.g., homogeneity of included studies) for valid conclusions relative to a head-to-head evaluation of interventions in a high-quality RCT. However, the results of all the five SRs3,4,7–9 and the one RCT6 included in this report consistently showed that adalimumab was less effective than the infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab and secukinumab agents for skin clearance and improvements in the psoriasis-related quality of life for patients with moderate- to-severe psoriasis, suggesting that a similar finding is likely from further studies. There was not enough information about the long-term safety and effectiveness of the reviewed biologic treatments.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Five SRs3,4,7–9 and one RCT6 provided the information in this report. The comparative skin clearing effectiveness of adalimumab versus infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, and secukinumab in patients with moderate- to-severe psoriasis was assessed using the PASI and the PGA (0, 1) tools. Evidence from the SRs3,4,7–9 and the RCT6 indicated that adalimumab was the least effective for skin clearance among the five compared biologic agents based on PASI3,4,6,7,9 or PGA3,6–9 results.

The comparative effectiveness of adalimumab for improving the psoriasis-related quality of life was compared to that of infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, and secukinumab in using DLQI scores of 0 or 1 (i.e., no effect on the patient’s life). Evidence from four SRs3,7–9 and the RCT6 indicated that adalimumab was the least effective among the five compared biologic agents for improving the health-related quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis among the five compared biologic agents.

On safety, the three SRs7–9 generally did not indicate a clear difference in safety parameters assessed between adalimumab and infliximab, ixekizumab, or secukinumab, with one exception; in one SR8 ixekizumab and infliximab were shown to be associated with higher odds of withdrawal due to adverse events compared with adalimumab, whereas the odds of withdrawal were comparable between adalimumab and secukinumab. The other two SRs7,9 did not report data comparing the safety of adalimumab to any other biologics. Rather, results of comparing each biologic to placebo was provided. Overall, there was not enough evidence to draw a firm conclusion about the comparative safety of adalimumab versus the other biologics of interest. The evidence from the included RCT6 suggested that the frequencies of AEs with risankizumab was not statistically significantly different from that of adalimumab in the short-term (up to 44 weeks). There were no long-term data on safety or efficacy.

Overall, there was consistent evidence from the studies3,4,6–9 included in this report indicating that adalimumab was less effective than infliximab, ixekizumab, risankizumab, and secukinumab in achieving skin clearance and improvements in health-related quality of life in patients diagnosed with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. However, there was a substantial overlap of the primary studies across the SRs.3,4,7–9 Thus, the pooled estimates from the separate SRs3,4,7–9 contain some data from the same primary studies.

The assessment of the methodological quality of four SRs4,7–9 and the RCT6 did not find issues that present significant uncertainty about the finding they reported. The quality of one SR3 was limited due poor reporting. However, the results from that SR3 were consistent with the other included studies and did not appear likely to impact the reported evidence, which may be due to the substantial overlap of primary studies across the SRs.3,4,7–9

These findings, in combination with other factors such as cost-effectiveness and patients’ preferences, may help decision-makers develop policies on the place in therapy of biologic agents, including the use of a tiering approach to optimize treatment outcomes for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

References

- 1.

- 2.

Loos

AM, Liu

S, Segel

C, Ollendorf

DA, Pearson

SD, Linder

JA. Comparative effectiveness of targeted immunomodulators for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018

Jul;79(1):135–144.e137. [

PubMed: 29438757]

- 3.

Warren

RB, See

K, Burge

R, et al. Rapid response of biologic treatments of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a comprehensive investigation using Bayesian and Frequentist network meta-analyses.

Dermatol Ther. 2020

Feb;10(1):73–86. [

PMC free article: PMC6994587] [

PubMed: 31686337]

- 4.

Sawyer

LM, Cornic

L, Levin

LA, Gibbons

C, Moller

AH, Jemec

GB. Long-term efficacy of novel therapies in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of PASI response.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019

Feb;33(2):355–366. [

PMC free article: PMC6587780] [

PubMed: 30289198]

- 5.

Hendrix

N, Ollendorf

DA, Chapman

RH, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Targeted Pharmacotherapy for Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis.

J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018

Dec;24(12):1210–1217. [

PMC free article: PMC10398188] [

PubMed: 30479197]

- 6.

Reich

K, Gooderham

M, Thaci

D, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 2019

Aug;394(10198):576–586. [

PubMed: 31280967]

- 7.

Xu

G, Xia

M, Jiang

C, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of thirteen biologic therapies for patients with moderate or severe psoriasis: a network meta-analysis.

J Pharmacol Sci. 2019

Apr;139(4):289–303. [

PubMed: 30922656]

- 8.

Jabbar-Lopez

ZK, Yiu

ZZN, Ward

V, et al. Quantitative evaluation of biologic therapy options for psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.

J Invest Dermatol. 2017

Aug;137(8):1646–1654. [

PMC free article: PMC5519491] [

PubMed: 28457908]

- 9.

Nast

A, Jacobs

A, Rosumeck

S, Werner

RN. Efficacy and Safety of Systemic Long-Term Treatments for Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

J Invest Dermatol. 2015

Nov;135(11):2641–2648. [

PubMed: 26046458]

- 10.

Kim

IH, West

CE, Kwatra

SG, Feldman

SR, O’Neill

JL. Comparative efficacy of biologics in psoriasis: a review.

Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012

Dec;13(6):365–374. [

PubMed: 22967166]

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

Shea

BJ, Reeves

BC, Wells

G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both.

BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. [

PMC free article: PMC5833365] [

PubMed: 28935701]

- 14.

Jansen

JP, Trikalinos

T, Cappelleri

JC, Daw

J, Andes

S. Indirect treatment comparison/network meta-analysis study questionnaire to assess relevance and credibility to inform health care decision making: An ISPOR-AMCP-NPC Good Practice Task Force Report.

Value Health. 2014

Mar;17(2):157–173. [

PubMed: 24636374]

- 15.

Downs

SH, Black

N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions.

J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. [

PMC free article: PMC1756728] [

PubMed: 9764259]

- 16.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 17.

- 18.

Nast

A, Jacobs

A, Rosumeck

S, Werner

RN. Efficacy and safety of systemic long-term treatmentsfor moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis: supplementary material.

J Invest Dermatol. 2015

Nov;135(11):1–28. [

PubMed: 26046458]

- 19.

- 20.

- 21.

Jansen

JP, Trikalinos

T, Cappelleri

JC, et al. Appendix A: Questionnaire to assess the relevance and credibility of a network meta-analysis. Value Health. 2014;17(2):Supplementary Material.

- 22.

Paul

C, Griffiths

C, van de Kerkhof

P, et al. Ixekizumab provides superior efficacy compared with ustekinumab over 52 weeks of treatment: results from IXORA-S, a phase 3 study.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019

Jan;80(1):70–79.e73. [

PubMed: 29969700]

- 23.

Bagel

J, Nia

J, Hashim

P, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (16-week CLARITY results)

Dermatol Ther. 2018

Dec;8(4):571–579. [

PMC free article: PMC6261116] [

PubMed: 30334147]

- 24.

Gordon

KB, Strober

B, Lebwohl

M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials.

Lancet. 2018

Aug;392(10148):650–661. [

PubMed: 30097359]

- 25.

Langley

RG, Papp

K, Gooderham

M, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous every-2-week dosing of ixekizumab over 52 weeks in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in a randomized phase III trial (IXORA-P).

Br J Dermatol. 2018

Jun;178(6):1315–1323. [

PubMed: 29405255]

- 26.

Blauvelt

A, Papp

KA, Griffiths

CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017

Mar;76(3):405–417. [

PubMed: 28057360]

- 27.

Cai

L, Gu

J, Zheng

J, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Chinese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017

Jan;31(1):89–95. [

PMC free article: PMC5215651] [

PubMed: 27504914]

- 28.

Lacour

J, Paul

C, Jazayeri

S, et al. Secukinumab administration by autoinjector maintains reduction of plaque psoriasis severity over 52 weeks: results of the randomized controlled JUNCTURE trial.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017

May;31(5):847–856. [

PubMed: 28111801]

- 29.

Reich

K, Armstrong

AW, Foley

P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: Results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017

Mar;76(3):418–431. [

PubMed: 28057361]

- 30.

Reich

K, Pinter

A, Lacour

J, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: 24-week results from IXORA-S, a phase III study.

Br J Dermatol. 2017

Oct;177(4):1014–1023. [

PubMed: 28542874]

- 31.

Augustin

M, Abeysinghe

S, Mallya

U, Qureshi

A, Roskell

D, McBride

D. Secukinumab treatment of plaque psoriasis shows early improvement in DLQI response - results of a phase II regimen-finding trial.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016

Apr;30(5):645–649. [

PMC free article: PMC4814339] [

PubMed: 26660143]

- 32.

Blauvelt

A, Reich

K, Tsai

T, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis up to 1 year: results from the CLEAR study.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017

Jan;76(1):60–69.e69. [

PubMed: 27663079]

- 33.

Gordon

K, Blauvelt

A, Papp

K, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis

N Engl J Med. 2016

Jun;375(4):345–356. [

PubMed: 27299809]

- 34.

Gottlieb

A, Blauvelt

A, Prinz

J, et al. Secukinumab self-administration by prefilled syringe maintains reduction of plaque psoriasis severity over 52 weeks: results of the FEATURE trial.

J Drugs Dermatol. 2016

Oct;15(10):1226–1234. [

PubMed: 27741340]

- 35.

Mease

PJ, van der Heijde

D, Ritchlin

CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1.

Ann Rheum Dis. 2017

Jan;76(1):79–87. [

PMC free article: PMC5264219] [

PubMed: 27553214]

- 36.

Blauvelt

A, Shi

N, Zhu

B, et al. Comparison of Health Care Costs Among Patients with Psoriasis Initiating Ixekizumab, Secukinumab, or Adalimumab.

J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019

Dec;25(12):1366–1376. [

PMC free article: PMC10398217] [

PubMed: 31778621]

- 37.

Gordon

KB, Duffin

KC, Bissonnette

R, et al. A Phase 2 Trial of Guselkumab versus Adalimumab for Plaque Psoriasis.

N Engl J Med. 2015

Jul;373(2):136–144. [

PubMed: 26154787]

- 38.

Griffiths

C, Reich

K, Lebwohl

M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials.

Lancet. 2015

Aug;386(9993):541–551. [

PubMed: 26072109]

- 39.

Paul

C, Lacour

J, Tedremets

L, et al. Efficacy, safety and usability of secukinumab administration by autoinjector/pen in psoriasis: a randomized, controlled trial (JUNCTURE)

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015

Jun;29(6):1082–1090. [

PubMed: 25243910]

- 40.

Thaçi

D, Blauvelt

A, Reich

K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015

Sep;73(3):400–409. [

PubMed: 26092291]

- 41.

Langley

R, Elewski

B, Lebwohl

M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials.

N Engl J Med. 2014

Jul;371(4):326–338. [

PubMed: 25007392]

- 42.

Ohtsuki

M, Morita

A, Abe

M, et al. Secukinumab efficacy and safety in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: subanalysis from ERASURE, a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study

J Dermatol. 2014

Dec;41(12):1039–1046. [

PubMed: 25354738]

- 43.

Papp

KA

Langley

RG, Sigurgeirsson

B, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II dose-ranging study.

Br J Dermatol. 2013

Feb;

168(2):412–421. [

PubMed: 23106107]

- 44.

Rich

P, Sigurgeirsson

B, Thaci

D, et al. Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II regimen-finding study.

Br J Dermatol. 2013

Feb;168(2):402–411. [

PubMed: 23362969]

- 45.

Leonardi

C, Matheson

R, Zachariae

C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis.

N Engl J Med. 2012

Mar;366(13):1190–1199. [

PubMed: 22455413]

- 46.

Yang

H, Wang

K, Jin

H, et al. Infliximab monotherapy for Chinese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial

Chin Med J. 2012

Jun;125(11):1845–1851. [

PubMed: 22884040]

- 47.

Asahina

A, Nakagawa

H, Etoh

T, Ohtsuki

M, Adalimumab

MSG. Adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a Phase II/III randomized controlled study.

J Dermatol. 2010;37(4):299–310. [

PubMed: 20507398]

- 48.

Torii

H, Nakagawa

H, Japanese Infliximab Study Investigators. Infliximab monotherapy in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial.

J Dermatol Sci. 2010

Jul;59(1):40–49. [

PubMed: 20547039]

- 49.

Feldman

SR, Gottlieb

AB, Bala

M, et al. Infliximab improves health-related quality of life in the presence of comorbidities among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.

Br J Dermatol. 2008

Sep;159(3):704–710. [

PubMed: 18627375]

- 50.

Menter

A, Tyring

SK, Gordon

K, et al. Adalimumab therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized, controlled phase III trial.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008

Jan;58(1):106–15. [

PubMed: 17936411]

- 51.

Saurat

JH, Stingl

G, Dubertret

L, et al. Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION).

Br J Dermatol. 2008

Mar;158(3):558–566. [

PubMed: 18047523]

- 52.

Menter

A, Feldman

SR, Weinstein

GD, et al. A randomized comparison of continuous vs. intermittent infliximab maintenance regimens over 1 year in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007

Jan;56(1):31.e1–15. [

PubMed: 17097378]

- 53.

Revicki

D, Willian

MK, Saurat

JH, et al. Impact of adalimumab treatment on health-related quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes: results from a 16-week randomized controlled trial in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Br J Dermatol. 2008

Mar;158(1):549–557 [

PubMed: 18047521]

- 54.

Shikiar

R

Heffernan

M, Langley

RG, Willian

MK, Okun

MM, Revicki

DA. Adalimumab treatment is associated with improvement in health-related quality of life in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a Phase II randomized controlled trial.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(1):25–31. [

PubMed: 17365264]

- 55.

Gordon

KB

Langley

RG, Leonardi

C, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: double-blind, randomized controlled trial and open-label extension study.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006

Oct;55(4):598–606. [

PubMed: 17010738]

- 56.

Reich

K, Nestle

FO, Papp

K, et al. Improvement in quality of life with infliximab induction and maintenance therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial.

Br J Dermatol. 2006

Jun;154(6):1161–8. [

PubMed: 16704649]

- 57.

Feldman

SR

Gordon

KB, Bala

M, et al. Infliximab treatment results in significant improvement in the quality of life of patients with severe psoriasis: a doubleblind placebo-controlled trial.

Br J Dermatol. 2005

May;152(5):954–960. [

PubMed: 15888152]

- 58.

Reich

K, Nestle

FO, Papp

K, et al. Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial.

Lancet. 2005

Oct;366(9494):1367–74. [

PubMed: 16226614]

- 59.

Chaudhari

U, Romano

P, Mulcahy

LD, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomised trial.

Lancet. 2001

Jun;357(9271):1842–1847. [

PubMed: 11410193]

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- AMSTAR

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews

- CDR

Common Drug Review

- CI

Confidence interval

- CrI

Credible interval

- DLQI

Dermatology life quality index

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- IL

Interleukin

- ISPOR

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research

- MD

Mean

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- NMA

Network meta-analysis

- PASI

Psoriasis Area Severity Index

- PASI 100

100% improvement in PASI score

- PASI 75

≥75% improvement in PASI score

- PASI 90

≥90% PASI score

- PGA

Physician’s global assessment

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- RR

Risk ratio

- SAE

Serious adverse event

- SD

Standard deviation

- SR

Systematic review

- WDAE

Withdrawal due to adverse event

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Adalimumab for adult patients with plaque psoriasis: a review of clinical effectiveness. Ottawa: CADTH; 2020 Jun. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.