Continuing Education Activity

The jugular venous examination is a vital component of the cardiovascular exam. This activity outlines the identification and assessment of jugular venous distension. It highlights the importance of early diagnosis and the role of a skilled healthcare professional team in evaluating and treating patients with jugular venous distension.

Objectives:

- Identify the anatomical structures, indications, and technique assessment of jugular venous distension.

- Describe the equipment, personnel, preparation, and technique in regard to jugular venous distension.

- Outline the appropriate evaluation of the technique, position, and waveforms of jugular venous distension.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to measure jugular venous distention and improve outcomes.

Introduction

With recent technological advances, physicians may overlook the importance of the physical examination (PE). PE is of considerable significance and can yield important data necessary for the diagnosis and treatment. Upon initial presentation, a comprehensive physical examination is warranted. However, subsequent evaluations may be focused and problem-oriented. The cardiac examination is a component of physical examination and is an invaluable tool in assessing the hemodynamic status of the patient. The jugular venous examination is a vital component of the cardiovascular exam. When performed carefully and properly, the jugular venous waveform can provide an estimate of central venous pressure (CVP) and, when it is distended, can provide prognostic implications in patients with heart failure.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy

To perform an accurate assessment of jugular venous distension, one must appreciate and understand the anatomy of the jugular vein and its relation to other structures in the neck. The jugular vein is considered a central vein in the body. Central veins are thin-walled, distensible reservoirs and act as a conduit of blood in continuity with the right atrium. The jugular vein divides into external and internal.

The internal jugular vein forms from the inferior petrosal sinus and sigmoid sinus at the base of the skull and exits via the jugular foramen. The internal jugular vein (IJV) runs between the sternal and clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. A shallow defect between these landmarks can make the identification of IJV easier. It descends in the carotid sheath in the neck, lateral to the carotid artery, and drains into the subclavian vein to form a brachiocephalic vein at the base of the neck.

The external jugular vein forms from the posterior auricular vein and the posterior branch of the retromandibular vein behind the angle of the mandible. It runs obliquely across the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the superficial fascia of the neck and drains into the subclavian vein. In contrast to IJV, it can be easily visualized but is often not used to measure central venous pressure.

Technique

Approach to examination:

Evaluation of jugular venous pressure (JVP) involves observing the patient's jugular vein in the patient's neck in varying degrees of positions and maneuvers, estimating right atrial pressure, and determining abnormalities in the jugular venous column.

Position:

The examiner stands at the right side of the table because the right-sided internal jugular vein connecting to the right brachiocephalic vein is in direct line with the superior vena cava. Left IJ can be used if right-sided IJ is not visible. The left brachiocephalic vein, which connects the left IJV, crosses the mediastinal structures before draining into the superior vena cava and may be distended when there is partial obstruction of the mediastinal structures.

The patients are positioned supine initially on the bed that is bent at the hip so that when the head of the bed is elevated, the head, neck, and thorax are on a similar plane.

The head should be slightly tilted away from the examiner (left if examining from the right), and the neck should be in extension with the sternocleidomastoid relaxed. A penlight can help to enhance visualization.

Jugular venous pressure (JVP) is ideally measured in different planes. The degree of upper body elevation (0 to 90 degrees) is the angle at which the venous meniscus can be best appreciated in the neck. When a patient is supine, low venous pressure can be appreciated, with high venous pressure readily visible when the patient is upright (90 degrees). Recommendations are to change the head of the bed through various angles to appreciate JVP. If venous pressure is seen at the clavicle when the patient is upright, it suggests an elevated JVP[2], and sometimes, when the pressure is very high, it can be appreciated below the ear.

JVP varies with respiration, with inspiration generally decreasing the pressure. In some patients, it might not decrease or may even increase, a finding called the "Kussmaul sign." It can occur in patients with constructive or effusive pericarditis, restrictive pericarditis, RV infarction, severe RV dysfunction, massive pulmonary embolism, severe tricuspid regurgitation, tricuspid stenosis, and cardiac tamponade.

External Jugular Vein vs. Internal Jugular Vein

The external jugular vein (EJV) is an option when IJV is inappropriate. After identifying EJV, the forefinger should be placed above the clavicle on the vein; the venous column gets distended because of the blood coming from cerebral circulation. At this point, a second finger should be used to occlude the vein superiorly to prevent overdistension, and the finger at the clavicle should be released. Venous pressure is now measured since it approximates the vertical distance between the upper level of the fluid column and the right atrium, estimated to be 5 to 6 cm behind the angle of Louis.

The IJV can be differentiated from the carotid artery by palpating radial pulse, where single upstroke systole coincides. Unlike carotid pulse, IJV is not palpable and varies with respiration. The IJV impulse has three upstrokes a, c and v, and two descents x and y.

Waveforms of JVP signify the following:

a - presystolic, produced by right atrial contraction

c - (isovolumic phase) bulging of the tricuspid valve into the right atrium during ventricular systole

v - occurs in late systole; increased blood in the right atrium from venous return

Descents

x - a combination of atrial relaxation, downward movement of the tricuspid valve, and ventricular systole

y - the tricuspid valve opens, and the blood flows into the right ventricle.

When these are transmitted to the skin, a series of flickers are visible throughout the overlying skin. Once we have identified the IJV, we must estimate the venous pressure (VP). Normal VP is 1 to 8 cm of water.

Pathological conditions associated with abnormal waveforms:

The 'a' wave is absent in patients with atrial fibrillation because of lost atrial contraction. A large 'a' wave presents in patients with resistance to atrial contraction, such as pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid stenosis, or right atrial mass or thrombus. Cannon' a' wave is when the right atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve, such as in patients with complete AV block, premature atrial/ventricular/junctional beat, or ventricular tachycardia.

A large 'v' wave is seen in tricuspid regurgitation when the right ventricle contracts and the tricuspid valve does not completely close, which results in the shooting of blood back to the right atrium.

JVP is one of the most common and readily available tools to measure right atrial pressure (RAP) and can be used to assess volume status, especially hypervolemic states, due to cardiac etiologies.

Right atrial pressure (RAP) is measured by adding the height of the venous column above the angle of Louis to the vertical distance between the sternal angle and the mid-right atrium. The vertical distance between the sternal angle and mid-right atrium varies according to the position of the patient; it is 5 cm, 8 cm, and 10 cm when the patient is at 0 (supine), 30, and 45, respectively[3]. Generally, 5 cm is used as an approximate measurement, albeit it can be underestimated if used for all patients at all levels of elevation of the head (4).

Hence RAP is estimated with the following formula:

Estimated RAP (in cm of water) = (JVP height) + 5 cm.

Some of the causes of elevated RAP include RV failure (cardiomyopathy), cor pulmonale, pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid valve disease, constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid valve incompetence, and tricuspid valve stenosis or obstruction.

Indications

Jugular venous pressure measurement is a part of the cardiovascular examination, although its utility varies among the examiner and clinical setting. Its most common use is to estimate the right atrial pressure, especially in patients with heart failure, and also to measure the response to diuretic therapy. It is also helpful in the evaluation of conditions such as superior vena cava obstruction, tricuspid valve disease, and pericardial disease.

Equipment

- Gloves

- Drape

- Penlight

- Centimeter ruler and tape measure

Clinical Significance

With rapid advances in technology for diagnostic testing, providers have become less attentive to the bedside evaluation of physical signs. Measuring jugular venous pressure requires close observation and assessment.[4] It can give insight into the hemodynamic status of the heart, especially when a patient has heart failure exacerbation, which causes an increase in right atrial pressure, which becomes reflected in the jugular venous column. This metric is simply the most readily available and repeatable tool to assess CVP. Although assessment and measurement of pressure can highly vary from patient to patient, the ability to diagnose rapidly is achievable through experience. Hence, learning to diagnose and prognosticate based on physical examination can help avoid invasive diagnostic tests.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Measuring jugular venous pressure is perhaps the most difficult yet important physical diagnostic tool that yields vital information about the cardiac status of a patient. It comes with persistent practice and experience. A skilled healthcare professional should teach other physicians/nurses to identify and measure JVP in normal and in patients with elevated JVP. Rapid identification can not only aid in the quick diagnosis, but it can also help take necessary measures to treat the underlying condition and prevent complications.

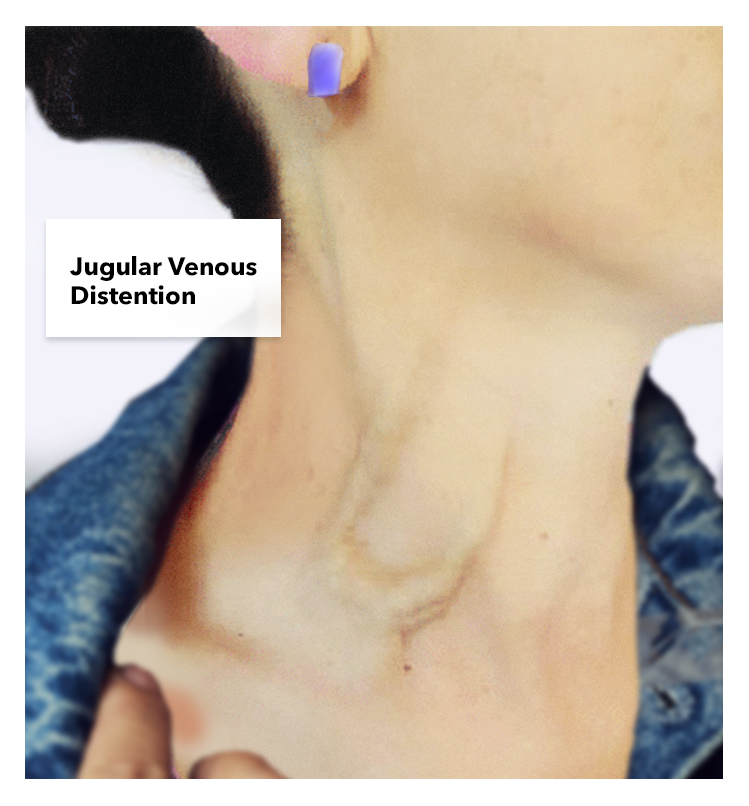

Figure

Jugular Venous Distention Contributed by Katherine Humphreys

References

- 1.

- Drazner MH, Rame JE, Stevenson LW, Dries DL. Prognostic importance of elevated jugular venous pressure and a third heart sound in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 23;345(8):574-81. [PubMed: 11529211]

- 2.

- Sinisalo J, Rapola J, Rossinen J, Kupari M. Simplifying the estimation of jugular venous pressure. Am J Cardiol. 2007 Dec 15;100(12):1779-81. [PubMed: 18082526]

- 3.

- Devine PJ, Sullenberger LE, Bellin DA, Atwood JE. Jugular venous pulse: window into the right heart. South Med J. 2007 Oct;100(10):1022-7; quiz 1004. [PubMed: 17943049]

- 4.

- Metkus TS, Kim BS. Bedside Diagnosis in the Intensive Care Unit. Is Looking Overlooked? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015 Oct;12(10):1447-50. [PMC free article: PMC4627420] [PubMed: 26389653]

Disclosure: Shwetha Gopal declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Shivaraj Nagalli declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Publication Details

Author Information and Affiliations

Authors

Shwetha Gopal1; Shivaraj Nagalli2.Affiliations

Publication History

Last Update: July 25, 2023.

Copyright

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Publisher

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

NLM Citation

Gopal S, Nagalli S. Jugular Venous Distention. [Updated 2023 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.