Abbreviations

- AS

aortic stenosis

- SAVR

surgical aortic valve replacement

- TAVI

transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Context and Policy Issues

Aortic stenosis is a type of heart valve disease in which the aortic valve narrows and reduces blood flow to the heart. Symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and fatigue can be experienced as the heart works harder to pump blood to the body. Without intervention, severe aortic stenosis can be fatal.1

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is currently the recommended treatment for individuals with aortic stenosis who are low or intermediate surgical risk.1 With SAVR, cardiac surgeons replace the damaged valve through an incision in the chest. Recovery from SAVR typically includes a five to seven day hospital stay, and an at home recovery of up to 12 weeks.2

For those who are at high surgical risk, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as a clinically effective treatment option.1 In Canada, TAVI is typically conducted by dedicated heart teams which include (at minimum) an interventional cardiologist, a cardiac surgeon, and an anesthesiologist.3 The procedure involves placing an artificial valve inside patients’ existing valve using a catheter, typically through an artery in the leg. Recovery from TAVI is typically shorter than SAVR, with a shorter hospital stay and shorter at home recovery (approximately four weeks).1

At present, TAVI is standard care for those at high surgical risk. However, improvements in the devices (catheters, balloons, and valves) used in TAVI have contributed to reduced risks of complications and improved outcomes.4 As result, there is growing interest in the use of TAVI in populations with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis who are at low or intermediate surgical risk. As these persons would be potentially eligible for TAVI and for SAVR, the expanding use of TAVI in these populations introduces additional considerations about supporting patients’ treatment decision making.

The purpose of this report is to describe patients’ and health care providers’ experiences with and perspectives on TAVI, in particular issues relating to communication, treatment decision making, and reflections on experiences post-TAVI.

Research Questions

Two sets of research questions guided this review:

How do people with aortic stenosis experience transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)? What are their perspectives on, expectations of, and preferences for TAVI? When making a decision about TAVI, what is involved and what do patients consider? What is their understanding of their health condition and the procedure?

How do health care providers who care for people with aortic stenosis experience TAVI? What are their perspectives on, expectations of, and preferences for communicating and supporting decision making around TAVI?

Key Findings

When deciding whether to undergo TAVI, patients reflected on the impact of their symptoms on their daily lives. Patients expected TAVI would afford them a longer life and a return to the activities that gave their lives meaning. They considered their prior health care experiences and those of their family members and friends, and how interventions had led to improved health. Although some chose to make the decision alone, many patients involved close family and adult children in their decision making. Trust in their physician helped patients feel confident in the decision-making process and their choice, and reduced worries about risk.

Patients can encounter logistical challenges when accessing TAVI through the need to travel to specialist centres in urban areas. Patients described the importance of having a caregiver available for them at discharge and during the recovery period.

Patients described experiencing a ‘new lease on life’ when they had rapid recovery and improvement in symptoms post-TAVI. But patients who had long hospital stays, and/or slow or no symptom improvement from TAVI struggled to reconcile their expectations with their actual experience. Figuring prominent amongst those whose expectations were not met was the way that, post-TAVI, the impact of comorbidities on their health and lives became clearer.

From the limited information available on health care providers’ perspectives, physicians appear to value TAVI for its short recovery time but expressed concerns about the use of TAVI for younger patients due to the lack of long-term data on the durability of valves.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted by an information specialist on key resources including Medline via OVID, EMBASE via OVID, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, the websites of Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. The search strategy was comprised of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concept was transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Search filters were applied to limit retrieval to qualitative studies. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2009 and July 31, 2019.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and the full-text of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Inclusion Criteria using SPIDER.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria outlined in , were duplicate publications reporting on the exact same data and same findings or were published prior to 2009.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

One reviewer assessed the quality of the included publications. An assessment of credibility, trustworthiness and transferability of the studies was guided by the ten items from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist.6 Results of the critical appraisal were not used to exclude studies from this review; rather they were used to understand the methodological and conceptual limitations of the included publications in specific relation to this review. In particular, the critical appraisal contributed to the analysis by identifying the limits of transferability of the results of included publications to this review.

Data Analysis

A framework analysis was used to organize and analyze results of the included studies.7 The a priori framework consisted of orienting concepts identified through project scoping, which included reading background materials on TAVI and the policy issues related to expanding the use of TAVI to populations at low and intermediate surgical risk. Concepts in the initial framework related to the process of making a decision to undergo TAVI from patients’ and health care providers’ perspectives included: information and understanding of the procedure and condition; issues relating to communication, and expectations of TAVI. Concepts related to patients’ experiences of TAVI itself included: perceptions and experiences of recovery; issues around the ability to resume activities of daily life, and views on quality of life.

One reviewer conducted the analysis. Included primary studies were read and re-read to identify key findings and concepts that mapped on the framework, which was modified as new concepts emerged. During the reading and re-reading of studies, memos were made, noting details and observations about the study’s methodology, findings, and interpretations, and connections to other studies and concepts in the framework. Diagramming was used to explore how emerging concepts mapped across study findings and across concepts. Using these techniques, concepts were re-ordered and organized into thematic categories. Re-reading, memoing and diagramming continued until themes were appropriately described and supported by data from the included publications. During the analysis, issues with transferability and the results of the critical appraisal were reflected on to aid with interpretation. The objective of the analysis was to identify and describe categories of findings that offer insight into decision making around and experiences of undergoing TAVI from patients’ and health care providers’ perspectives.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

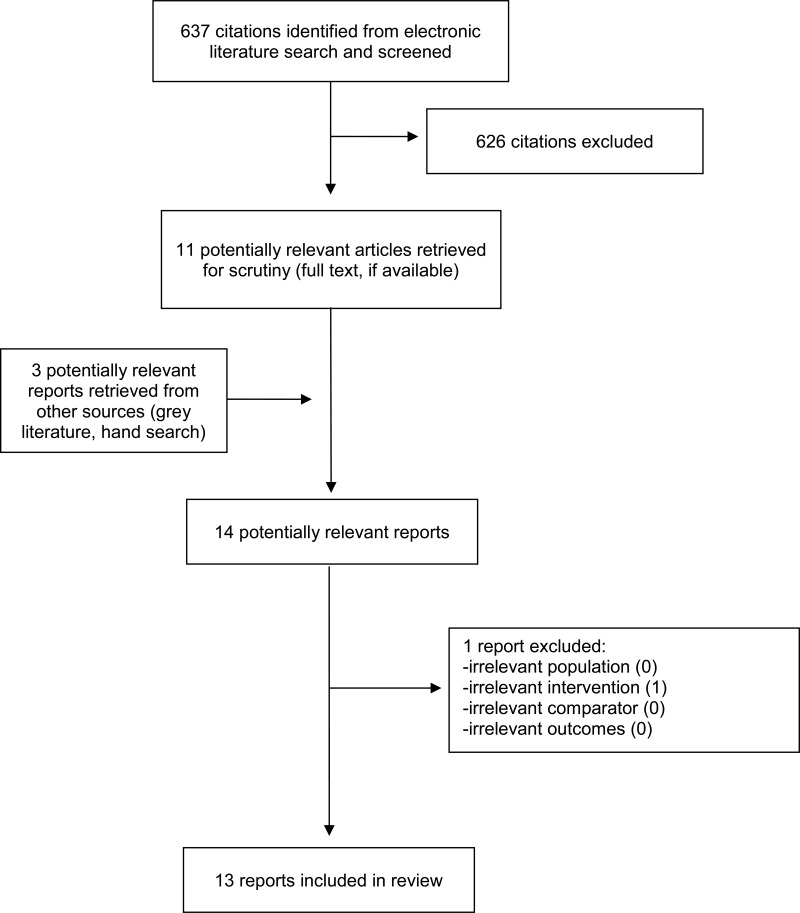

A total of 637 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 626 citations were excluded and 11 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. An additional three potentially relevant publications were identified through hand searching reference lists of potentially included studies and were retrieved for full text review. Of these 14 potentially relevant articles, publication was excluded because the focus was an irrelevant intervention, and 13 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA8 flowchart of the study selection process.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Details regarding the characteristics of included publications and their participants are provided in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Study Design and Data Collection

Authors of six publications did not report the study design used.9–14 Three described their study design as qualitative description,15–17 and two as phenomenology.18,19 One publication was a mixed methods study,20 and another was reported as a grounded theory study.21 All studies used semi-structured, in-depth interviews to collect data. Two publications interviewed patients prior to being assessed for eligibility for TAVI,11,12 two after being assessed as eligible but waiting for TAVI,13,15, and one after patients were told they were ineligible for TAVI.16 Seven studies interviewed patients after they had undergone TAVI.9,10,17–21 One study interviewed health care providers who had experience with TAVI.14

Country of Origin

Of the 13 included studies, seven were conducted in Sweden,9–12,16,18,21 two in Canada,15,17 and one each in the United Kingdom,20 United States,13 Denmark,19 and Germany.14

Study Population and Interventions

Twelve of the included publications represented 10 studies involving 247 patients.9–13,15–21 One study included patients and their relatives.17 One study included 10 health care providers (nine cardiologists and one cardiac surgeon).14

Twelve included studies included patients who were older adults diagnosed with severe aortic stenosis who were eligible for or had undergone TAVI.9–13,15–21 Four studies did not specify patients’ level of surgical risk.17,19–21 Of those that did, three studies reported on in four publications included patients who were high surgical risk and who elected for TAVI.10–13 One study reported on in two publications included patients who had undergone either SAVR or TAVI.9,18 One study reported including patients who were at low to high surgical risk, with a median surgical risk of intermediate.15 Two studies included patients who were either not eligible for or did not choose TAVI or SAVR.13,16

Summary of Critical Appraisal

In general, included publications were assessed to be of moderate to high quality. Details of the critical appraisal can be found in Appendix 4.

A key issue affecting the quality of individual studies was the timing of data collection. One study exploring decision making around TAVI only included the perspectives of those who chose TAVI and omitted those who did not.10 This reviewer judged that the study used recruitment strategies that were inappropriate and which would have affected the credibility of the findings as they did not capture the breadth of the phenomena of interest. Six publications from five studies were judged to have used data collection strategies that were inappropriate.9,10,13,17,18,20 This was because they conducted interviews at time points either in close proximity to or distant from the phenomena of interest which would have affected the dependability of the findings. The transferability of the results of the included studies and their relevance to the current review was limited in three publications from two studies9,16,18 because of a focus on elderly populations who were at high surgical risk and who were not representative of populations of low to intermediate surgical risk of specific interest in this review.

Summary of Findings

Patients’ decision making around TAVI

Patients’ expectations of TAVI were shaped by the severity their symptoms and how they impacted their daily lives

Patients described their severe AS as causing them to struggle with shortness of breath and fatigue which reduced their ability engage in social and physical activities and increased their dependence on others.11,12,15,20 Living with severe AS was challenging emotionally and mentally, and patients often described struggling with feelings of depression, loneliness, and worthlessness.12,15,20 Their poor physical and mental health, diminishing ability to do daily activities and increased dependence on family was a motivator for patients to explore interventions for their severe AS.10,12,15,20

When offered the opportunity to be assessed for TAVI, patients felt hopeful that something might be done for their condition, its symptoms and impact on their life.10,11,16,20 Those patients with severe AS hoped that they would live longer as a result of undergoing TAVI,13,15,20 but also hoped that they would have a “new lease on life.”(p. 490)15 This “new lease” was described by patients as being an improvement in their symptoms, offering the ability to increase their independence and resume their daily and social activities.10,15,20 As one patient put it, “I want to be able to garden, walk, do household chores… I want to live in my home independently.”(p. 1039)13 Much of the time, patients referred to the desire to resume specific activities they found meaningful (e.g., travel, walks, dancing), and hoped TAVI would provide them the opportunity to do so.12,13,15,16 Patients’ hopes for TAVI often expressed an underlying enthusiasm and zeal for living life to its fullest.10,21 For some, particularly those patients who struggled with other life-limiting and debilitating conditions, extending life was not necessarily viewed as desirable. As one patient with Parkinson’s disease stated that they “would rather die quickly of heart failure… Knowing what my options are with Parkinson’s, I don’t want to face a prolonged debilitated life.”(p. 1040)13 This highlights the ways in which patients’ hopes for and expectations of treatments for severe AS are dependent upon their physical and mental health as a whole and are not limited to AS.

Patients weighed risks and benefits of undergoing TAVI using information and their past health care experiences

Patients sought information on their condition and TAVI from physicians foremost, but also friends, relatives and the internet.11,15 Information also came from their previous experiences as patients. Patients referred to their previous experiences of heart interventions which had improved their health as why they hoped to undergo TAVI.15,16,21 For those who had experienced previous heart surgeries, they hoped TAVI would offer a quicker recovery.15 Short recovery was particularly appreciated by patients who had familial or domestic obligations that they wanted to return to.15 The benefit of quick recovery associated with TAVI did not appear prominently in patients’ weighing of risk and benefits, but may be attributed to the majority of patients being at high surgical risk and ineligible for SAVR.

Trust in their physicians played a large role in patients’ decision making

Patients often expressed trust in their physicians’ recommendation for TAVI and their skills as experts when sharing that they were not worried about the undergoing TAVI.11,12,21 One patient, when asked about his understanding of TAVI, replied: “I don’t know much about the heart, really. I can just go by what [Internist] tells me, eh? My doctor here. He’s a real good doctor, and I’ve got a lot of faith in him.” (p. 490)15

Patients felt respected when they had the ability to discuss their options with their physicians, were informed, and were able to participate meaningfully in treatment decision making.10,21 Having a long-standing relationship with their physicians was reported to have helped patients feel more comfortable and confident during decision making.11 Patients’ felt more trust in their physicians when they spent time sharing information and giving patients time to think through their decision.10 Thus trust was not necessarily a given, but had to be established through relationships and behaviours.10 When patients expressed a lack of confidence in their physicians’ skills, they often described being uncertain or ambivalent about undergoing TAVI.12 In some cases, patients sought second opinions to reduce this uncertainty and to have a physician they felt they could trust.10

When patients trusted their physicians, it helped them accept the risks of the procedure and feel confident in their decision to undergo TAVI. For some, this confidence placed the risks of TAVI outside of their control:10,12

I don’t feel anxious about the operation. Either it will go well, or it won’t. I hope I will survive and that I don’t have more problems than I have today. Of course, I want to survive, but that isn’t my decision. (p. 525)12

One study noted that a pattern of “obedience” appeared in some patients, where trust involved placing responsibility for the decision in others and outside of themselves. This was often due to patients’ lack of confidence or sense of the value of their own decisions.12 Trust in treatment decision making around TAVI appears as a prominent consideration in patients’ decision making. Trust in one’s physician involves being able to access desired information on risks and benefits, feeling secure with risks and the final decision, and is facilitated through communication and respectful relationships with their health care providers.

Family members, particularly adult children, were often involved in decision making

Many patients noted that they involved and even relied on the opinions of their relatives, particularly their adult children.12,15

You talk to the children and husband, and I say like this, ‘I don’t want to die on the operating table, my heart can beat as long as it can, and I won’t take any operation,’ but the way I feel today, and like my husband also said, ‘You can’t manage anything.’ I can’t do anything, I have no fortitude. So we decided that we should do this. (p.259)11

For those without partners, they felt the burden of being alone in their decision making.10 The decision to undergo TAVI or not was a struggle for many patients and the availability of family during that time was an important source of support.10,12,15

However, in some cases patients described how they chose not to discuss the matter with their family, as they did not want to be a burden.10,15 Their preference was to maintain their independence in decision making, so that they would ‘own’ the consequence of the decision.10

Some patients described undergoing TAVI as an obligation to their family.10 In one study where adult children were present at the intake to the assessment for TAVI, researchers noted that it was adult children who often offered the treatment goal of longer life, not the patients themselves.13 Taken together, this points to the importance of ensuring patients’ own treatment goals and decisions are incorporated into the discussion with physicians to ensure autonomous choice.

Patients’ Experiences of TAVI

Patients sometimes experienced challenges with the logistics of being assessed and undergoing TAVI

Patients described the logistical challenges of TAVI.15,17 These involved travel to a specialized TAVI centre for assessment and the procedure, and those who lived far away from the centre expressed concern about the costs of accommodation, long distance travel and the need to find someone to accompany them.15,17

Some patients described being surprised at being discharged so early after TAVI and that they were unprepared to go home.17 Others recommended that they had someone who could look after them during the at-home recovery period,17,19 particularly to monitor potential complications.17

When their expectations were met, patients felt TAVI gave them a second chance at life

Those patients who had a quick recovery described TAVI as easy, and were pleasantly surprised by how fast they recovered from the procedure and how it immediately improved their AS symptoms.17,19–21 As one patient put it, “It was nothing, as I say when people ask, a piece of cake and it went just fine and I was almost cured before I came home.”(p. 153)21 For patients who had a quick recovery and immediately experienced improvement in their symptoms, TAVI met their expectations and gave them their “new lease on life”:20 “Yes, it feels like I’ve got my life back a little, I have been given another chance…”20 In particular, patients’ symptoms of breathlessness improved, enabling them to sleep, breathe better, and have more energy. With renewed energy and ability to walk and be active, patients described becoming more social and independent.17,19–21

Patients looked forward to the future and once again doing the activities that gave their meaning life.21 This included changing their personal relationships upon which they had become dependent, to moving from caregiving to more intimate and reciprocal relations.20

For some, even though TAVI did not dramatically improve their symptoms and functioning, it did open doors for them to have other health interventions such as a hip replacement or tumour resection for which they were previously ineligible.13,20 Even when it did not reduce their symptoms as much as they had hoped, some patients described that having TAVI made them feel safe as something had been done to help their heart.19–21 This led them to feel as though they were able to travel and be physically active compared to how they were pre-TAVI.19–21

When their expectations were not met, patients had to reconcile their experiences with their expectations and did so in a number of ways

Patients were disappointed when they experienced a slow recovery or complications after TAVI that resulted in longer hospital stays.21 This was all the more so when they had had prior heart surgery and had expected a quicker recovery with TAVI.21 Some elderly patients experienced postoperative delirium after TAVI or SAVR and described how they desired close, supportive care from their health care providers and relatives.9,18 When this was not available, patients described experiencing emotional distress and feeling isolated, insecure and unsafe.9,18 Such complications and longer hospital stays contrasted with patients’ expectations of a quick recovery.

Patients who did not experience symptom changes immediately or shortly after TAVI continued to struggle with their symptoms. For some, this was during the early recovery period, where they felt weak and fatigued, sometimes even more so than before.17 Others continued to hold out hope for recovery: “I got good news from the doctor yesterday. He said: it can take a whole year before you get well. So it was a ray of hope, I think. You’ll think you’ll be fine at once but it takes time… “(p. 153)21 Again, these experiences of delayed recovery contrasted with the framing of TAVI as being easier and quicker to recovery from than SAVR.

When TAVI did not meet their expectations of symptom improvement and they were not able to resume activities that they had hoped to do, patients expressed disappointment13,17,21 and feeling depressed.17,21 One patient, when asked about what he had expected from TAVI, said “I’d be more realistic about what life was going to be like after… Because it’s very frustrating when you don’t expect it.” (p. 285)17 Regrets about undergoing TAVI sometimes accompanied disappointment, particularly where symptoms worsened.21

Even where TAVI resulted in improved symptoms from their AS, patients who had other comorbidities continued to face their symptoms and impact. While prior to TAVI symptoms of breathlessness and fatigue dominated, post-TAVI patients noticed more acutely how their other health conditions impacted their daily lives.17,19–21 A wife of one patient said: “We’re more than 100% satisfied and grateful, and it gave him a huge new quality of life. When he talks about being satisfied or disappointed, it’s because of his other conditions that disable him from doing the activities he loves to do.”(p. 282)17 Thus patients’ experiences of how TAVI affected their AS and their lives are interconnected with their health and well-being as a whole. Patients may have expected TAVI to lead to improvements not possible due to their heart or other comorbidities.

Physicians’ experiences with TAVI

One study focused on physicians’, primarily cardiologists, views on TAVI to explore how the procedure became diffused across German hospitals.14

There was variability in physicians’ experiences with patients’ familiarity with TAVI, with some suggesting that patients had requested TAVI, while others never having experienced that.14 One physician noted that that it was younger patients whom were typically requesting the procedure. Physicians saw TAVI as offering an advantage over SAVR due to the quick recovery period:

But it is an intervention in which the patient is basically walking around the next day. And with heart surgery that is, of course, very, very different. That’s it, especially for older persons… And I think the 80-year-old patient must quickly get out of the hospital and back into his environment and considering this, such a method has, of course, a huge advantage.14

These advantages aside, physicians still expressed concern about the use of TAVI in patients younger than 75 due to an insufficient evidence base, particularly on the duration of implanted valves.

TAVI was consistently viewed as a highly complex procedure with a steep learning curve that required a dedicated heart team.14 Physicians described pressure to adopt TAVI so their facility would be an early adopter and viewed as innovative. But implementation was a challenge because as a procedure, TAVI was seen as requiring a renegotiation of the roles and structure of interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. Successfully negotiating these relationships was seen as key to implementing TAVI within a hospital.

Limitations

Key limitations stem from issues around the transferability and relevance of the included studies to this review’s research questions. Many studies were focused on patients who were at high surgical risk, including patients who were ineligible for TAVI and SAVR. The reporting in studies that included patients at low or intermediate surgical risk made it difficult to assess differences in experiences by level of surgical risk. The interventions available to those patients at high surgical risk are not the same as those available to low and intermediate (i.e., SAVR is an option) which would affect decision making. A related issue is that the patient populations tended to focus on TAVI in older or elderly adults. Older and elderly adults share cohort experiences that shape their views and perceptions of health and health care that may not be shared by younger adults. This is likely to have an impact on how they access information, who they involve in decision making, and how they weigh the risks of a procedure with the long-term benefits across their life course.

One study was located that addressed health care providers’ experiences and perspectives. This allowed for reporting of these study results but not a synthesis of providers’ perspectives on TAVI.

Within the included studies, there was no analysis of differences in populations, for example sex, gender, socio-economic status, and ethnicity that may influence or shape patients’ experiences.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

This review used a framework analysis to synthesize the results of 13 included studies and described key facets of patients’ decision making around and experiences of TAVI for severe AS. When deciding whether to undergo TAVI, patients weighed the severity of their symptoms and its impact on their daily lives against their hopes for a longer and more active and independent life through TAVI. Their prior health care experiences and those of their family members and friends also informed patients’ decisions. Patients often involved close family and adult children in decision making, although sometimes preferred to do otherwise and not burden their family. Trust in one’s physician was consistently raised in conversations around decision-making. Trusting their physician facilitated patients to feel secure, informed and consulted in their decision. Where trust did not exist, patients tended to feel more worried, uncertain and ambivalent towards the decision to undergo TAVI.

When TAVI met patients’ expectations for rapid recovery and symptom relief, they described having a “new lease on life.” Even when symptom improvement and the ability to reengage in social and daily activities was limited, patients found themselves feeling more secure in their health and able to access interventions that they were previously ineligible for. When patients had long hospital stays, and/or slow or no improvement post-TAVI, they struggled to reconcile their hopes and expectations with their realities. For some, this involved being patient and continuing to hope for improvement, whereas for others it led to disappointment and regret. Figuring prominently amongst those whose expectations were not met was the way that, post-TAVI, the impact of comorbidities on their health and lives became clearer.

Limited information was available on physicians’ perspectives. From the one included study, it appears physicians appreciate the short recovery time for TAVI but expressed concerns about its use in younger patients in the absence of long-term data on valve durability.

The findings of this review illustrate specific opportunities to support patients in decision making around TAVI. The disjuncture between patients’ expectations and experiences of TAVI points to opportunities to support patients by ensuring information on potential benefits supports realistic and tailored expectations of potential health improvement. This is particularly important with patients with comorbidities as the health gains may be unclear in the context of other chronic health conditions. Similarly, as patients’ hopes for treatment are often related to very specific activities, eliciting these may help patients articulate their expectations of TAVI and help with decision making. Family members play a role in many patients’ decision making, but patients should be engaged from the onset to explore with whom they are sharing decision making and support their autonomous decisions. Physicians can support shared decision making through their interactions with patients and ensure that appropriate time is given for decision making.

In the case of patients deciding on TAVI versus SAVR, the findings of this review suggest that patients, particularly those with domestic or other caregiving obligations, are likely to appreciate the shorter recovery time of TAVI. This is likely to be a more prominent concern in adults who are still working or who are involved in caregiving for children or their parents.

Experiences of TAVI point to the types of issues patients confront when accessing TAVI and when recovering, and that the implementation of TAVI can support positive patient experiences. Heart Teams and hospitals can support patient travel by, for example, helping patients select appointment times that work best for their travel arrangements, particularly for those patients who must travel long distances and are often reliant upon the accompaniment of others. While patients appreciated the quick recovery, helping patients have discharge and home-recovery plans made in advance can reduce logistical challenges faced during recovery.

References

- 1.

Webb

J, Rodés-Cabau

J, Fremes

S, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement.

Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(5):520–528. [

PubMed: 22703948]

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

Cooke

A, Smith

D, Booth

A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis.

Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443. [

PubMed: 22829486]

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 9.

Instenes

I, Fridlund

B, Amofah

HA, Ranhoff

AH, Eide

LS, Norekval

TM. ‘I hope you get normal again’: an explorative study on how delirious octogenarian patients experience their interactions with healthcare professionals and relatives after aortic valve therapy.

Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18(3):224–233. [

PubMed: 30379104]

- 10.

Skaar

E, Ranhoff

AH, Nordrehaug

JE, Forman

DE, Schaufel

MA. Conditions for autonomous choice: a qualitative study of older adults’ experience of decision-making in TAVR.

J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(1):42–48. [

PMC free article: PMC5329732] [

PubMed: 28270841]

- 11.

Olsson

K, Naslund

U, Nilsson

J, Hornsten

A. Experiences of and coping with severe aortic stenosis among patients waiting for transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31(3):255–261. [

PubMed: 25658189]

- 12.

Olsson

K, Naslund

U, Nilsson

J, Hornsten

A. Patients’ decision making about undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe aortic stenosis.

J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31(6):523–528. [

PubMed: 26110543]

- 13.

Coylewright

M, Palmer

R, O’Neill

ES, Robb

JF, Fried

TR. Patient-defined goals for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a qualitative analysis.

Health Expect. 2016;19(5):1036–1043. [

PMC free article: PMC5054836] [

PubMed: 26275070]

- 14.

Merkel

S, Eikermann

M, Neugebauer

EA, von Bandemer

S. The transcatheter aortic valve implementation (TAVI)-a qualitative approach to the implementation and diffusion of a minimally invasive surgical procedure.

Implement Sci. 2015;10:140. [

PMC free article: PMC4596312] [

PubMed: 26444275]

- 15.

Lauck

SB, Baumbusch

J, Achtem

L, et al. Factors influencing the decision of older adults to be assessed for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: an exploratory study.

Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15(7):486–494. [

PubMed: 26498908]

- 16.

Olsson

K, Naslund

U, Nilsson

J, Hornsten

A. Hope and despair: patients’ experiences of being ineligible for transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019:1474515119852209. [

PubMed: 31113221]

- 17.

Baumbusch

J, Lauck

SB, Achtem

L, O’Shea

T, Wu

S, Banner

D. Understanding experiences of undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: one-year follow-up.

Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(3):280–288. [

PubMed: 29087216]

- 18.

Instenes

I, Gjengedal

E, Eide

LSP, Kuiper

KKJ, Ranhoff

AH, Norekval

TM. “Eight days of nightmares …” - octogenarian patients’ experiences of postoperative delirium after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement.

Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(2):260–266. [

PubMed: 28396186]

- 19.

Kirk

BH, De Backer

O, Missel

M. Transforming the experience of aortic valve disease in older patients: a qualitative study.

J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(7-8):1233–1241. [

PubMed: 30552729]

- 20.

Astin

F, Horrocks

J, McLenachan

J, Blackman

DJ, Stephenson

J, Closs

SJ. The impact of transcatheter aortic valve implantation on quality of life: a mixed methods study.

Heart Lung. 2017;46(6):432–438. [

PubMed: 28985898]

- 21.

Olsson

K, Naslund

U, Nilsson

J, Hornsten

A. Patients’ experiences of the transcatheter aortic valve implantation trajectory: a grounded theory study.

Nurs Open. 2018;5(2):149–157. [

PMC free article: PMC5867280] [

PubMed: 29599990]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Publications

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Study Objectives | Sample Size | Inclusion Criteria | Data Collection |

|---|

| Instenes, 2019, Sweden9* | NS | To explore the interactions with relatives and health care providers of octogenarian patients’ who experienced postoperative delirium after TAVI or SAVR | 10 patients at six-12 months post-discharge 5 patients at four years post-discharge with 5 patients being lost at follow-up | Patients aged 80 and older who had experienced postoperative delirium after undergoing TAVI or SAVR | Semi-structured interviews at six-12 months and again at four years post-discharge |

| Olsson, 2019, Sweden16 | Qualitative description | To explore patients’ experiences of being evaluated and ineligible for TAVI | 8 patients | Patients who were assessed for TAVI but were judged to be ineligible | In-depth interviews one-four weeks after being told they were ineligible for TAVI |

| Baumbusch, 2018, Canada17 | Qualitative description | To describe older adults and family caregivers’ perspectives on undergoing TAVI | 31 patients 15 caregivers | Patients who underwent TAVI and completed one-year follow-up | Semi-structured interviews one year after undergoing TAVI |

| Instenes, 2018, Sweden18* | Phenomenology | To explore how octogenarian patients experience postoperative delirium after TAVI or SAVR | 10 patients | Patients aged 80 and older who had experienced postoperative delirium after undergoing TAVI or SAVR | Semi-structured interviews at six-12 months post-discharge |

| Olsson, 2018, Sweden21 | Grounded theory | To explore how patients experienced the recovery process from TAVI | 19 patients | Patients who had undergone TAVI | In-depth interviews at 6-months post-TAVI |

| Astin, 2017, UK20 | Mixed methods: qualitative NS | To describe patients’ views on the impact of TAVI on their quality of life | 89 patients | Patients who underwent TAVI | Semi-structured interviews at 1 and at 3 months post-TAVI |

| Kirk, 2017, Denmark19 | Phenomenology | To explore patients’ lived experiences of daily life and coping with recovery after TAVI | 10 patients | Patients with AS who had been treated with TAVI | Interviews 3-4 months post-TAVI |

| Skaar, 2017, Norway10 | NS | To describe older adults’ experiences of decision making around TAVI | 10 patients | Patient who underwent TAVI and were ineligible for SAVR | Semi-structured interviews 2-4 weeks after TAVI |

| Lauck, 2016, Canada15 | Qualitative description | To explore factors influencing patients’ decision making to undergo eligibility assessment for TAVI | 15 patients | Patient who were 75 years old or older and referred for assessment of their eligibility for TAVI | Semi-structured interviews before assessment for eligibility for TAVI |

| Olsson, 2016, Sweden11** | NS | To describe patients’ experiences of coping with severe AS while waiting for TAVI | 24 patients | Patients who were eligible for and awaiting TAVI | Semi-structured interviews prior to TAVI |

| Olsson, 2016, Sweden12** | NS | To describe patients’ decision making to undergo TAVI | 24 patients | Patients who were eligible for and awaiting TAVI | Semi-structured interviews prior to TAVI |

| Coylewright, 2015, US13 | NS | To elicit and report patient-defined goals from elderly patient making treatment decisions for severe AS | 46 patients | Elderly patients (not defined) with severe AS and who were either at high surgical risk or were inoperable and who were assessed for TAVI | Responses to one open-ended question during clinical evaluation (pre-assessment for TAVI) |

| Merkel, 2015, Germany14 | NS | To describe factors influencing the uptake of TAVI in hospitals in Germany | 10 clinicians (9 cardiologists and 1 cardiac surgeon) | Cardiologists and cardiac surgeons working in hospitals and who have at least one year of experience with TAVI | Problem-centered interviews |

AS = aortic stenosis; NS = not specified; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation

- **

Interview data from Instenes 201818 are included in Instenes 20199

- ***

Olsson 201611 and Olsson 201611 use same interview data

Appendix 3. Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 3Characteristics of Study Participants

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Sample Size | Sex (% female) | Age range in years | Level of surgical risk; Surgery or intervention for AS |

|---|

| Instenes, 2019, Sweden9* | 5 patients (at 4 year post-discharge interview) | 20% (at 4 year post-discharge interview) | Mean age of 87 years (at 4 year post-discharge interview) | NS; 40% underwent TAVI, 60% underwent SAVR |

| Olsson, 2019, Sweden16 | 8 patients | 25% | 77-93 | High; patients were denied SAVR and TAVI |

| Baumbusch, 2018, Canada17 | 31 patients 15 caregivers | Patients: 58% Caregivers: 67% | Patients: 58-96 Caregivers: 56-95 | NS; TAVI |

| Instenes, 2018, Sweden18 | 10 patients | 50% | 81-88 years | NS; 40% underwent TAVI, 60% underwent SAVR |

| Olsson, 2018, Sweden21 | 19 patients | 42% | 60-90 | NS; TAVI |

| Astin, 2017, UK20 | 89 patients | 60% | Mean of 82 years | NS; TAVI |

| Kirk, 2017, Denmark19 | 10 patients | 60% | 72-87 | NS; TAVI |

| Skaar, 2017, Norway10 | 10 patients | 60% | 3 patients between 70-79 years of age and 7 between 80-89 years of age | High; TAVI |

| Lauck, 2016, Canada15 | 15 patients | 40% | 75-92 | Low to high (median intermediate); 53% underwent TAVI |

| Olsson, 2016, Sweden11,12** | 24 patients | 37% | Mean of 81 years of age | High; awaiting TAVI |

| Coylewright, 2015, US13 | 46 patients | 63% | 89% were older than 75 years of age Mean age 84 years | High; 39 patients underwent TAVI, 7 patients chose palliative care |

| Merkel, 2015, Germany14 | 9 cardiologists, 1 cardiac surgeon | NS | NS | NA |

AS = aortic stenosis; NA = not applicable; NS = not specified; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation

- **

Interview data from Instenes 201818 is included in Instenes 20199

- ***

Olsson 201611 and Olsson 201611 use same interview data

Appendix 4. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

View in own window

| Qualitative Studies Assessed Using CASP Qualitative Checklist6 |

|---|

| First Author, Year | Clear statement of the aims of the research? | Qualitative methodology appropriate? | Research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | Ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Clear statement of findings? | Relevant to the current review? |

|---|

| Instenes, 20199 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| Olsson, 201916 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Baumbusch, 201817 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Instenes, 201818 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Astin, 201720 | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + |

| Kirk, 201719 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Olsson, 201721 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Skaar, 201710 | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lauck, 201615 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| Olsson, 201611 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Olsson, 201612 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Coylewright, 201513 | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | - | + | + |

| Merkel, 201514 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis: a rapid qualitative review. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Sep. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Health Canada, Canada’s provincial or territorial governments, other CADTH funders, or any third-party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.