OVERVIEW

Introduction

Turmeric is a popular herb derived from the roots of the plant Curcuma longa found mostly in India and Southern Asia. Turmeric has an intense yellow color and distinct taste and is used as a dye as well as a spice in the preparation of curry. Turmeric and its purified extract curcumin are also used medically for their purported antiinflammatory and antioxidant effects to treat a wide variety of conditions and for general health and wellness. Turmeric and curcumin have been associated with a low rate of transient serum enzyme elevations during therapy and, while having a long history of safety, turmeric products have recently been implicated in several dozen instances of clinically apparent acute liver injury.

Background

Turmeric (tur mer' ik) is a widely used herbal product derived from the roots of Curcuma longa, a perennial plant belonging to the ginger family (Zingiberaceae) that is native to India but grown throughout Southern Asia and in central America. Extracts of the rhizomes of turmeric contain volatile oils and curcuminoids (such as curcumin, demethoxycurcumin and others) which are believed to be the active antiinflammatory components of the herb and are often collectively referred to as curcumin. Curcumin comprises between 1% and 6% by dry weight of whole turmeric extracts, other components being starch, fats, proteins, fiber, vitamins, minerals, and water. The antiinflammatory effects of turmeric and curcumin are thought to be mediated by inhibition of leukotriene synthesis. Curcumin has also been reported to have antineoplastic effects, mediated perhaps by inhibition of intracellular kinases. Turmeric has been used in traditional Indian (Ayurvedic) medicine to treat many conditions including indigestion, upper respiratory infections and liver diseases. Turmeric and curcumin are under active evaluation as antiinflammatory and antineoplastic agents, for treatment of diabetes and hyperlipidemia and as therapy of liver diseases including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). The scientific bases for the purported effects of turmeric are not well established and rigorous proof of its efficacy in any medical condition is lacking. Commercial preparations of turmeric and curcumin vary widely in curcuminoid content. The recommended daily dose varies widely (100 to >1,000 mg daily), depending on the preparation used (curcuminoids vs turmeric extract), formulation (tablets, liquid, root extract, tea) and indications. Side effects are uncommon and mild but may include dermatitis and gastrointestinal upset.

Hepatotoxicity

Both turmeric and curcumin were considered to be generally safe and for many years had not been linked to instances of liver injury in any consistent way. Studies of its use in various diseases showed low rates of transient and asymptomatic serum enzyme elevations during therapy, but without instances of clinically apparent acute liver injury. Indeed, turmeric was evaluated as a potential therapy of acute and chronic liver injury and although its efficacy and safety were not clearly shown, therapy with turmeric and curcumin did not seem to worsen the preexisting liver conditions. Recently, isolated case reports of liver injury arising during use of turmeric dietary supplements have been published. Initially, these episodes were attributed to other exposures that might have accounted for the injury or possible contaminants in the commercial turmeric products. One reason given for the safety and lack of hepatotoxicity of curcumin was that it is poorly absorbed by the oral route, and it was unclear whether there was adequate systemic exposure to achieve any of the purported beneficial or adverse effects of turmeric or curcumin.

Importantly, means of increasing the bioavailability of curcumin were developed using piperine (black pepper) or nanoparticle delivery methods to increase absorption. These high bioavailability forms of purified curcumin were subsequently linked to several cases of liver injury and mentioned as a possible cause of outbreaks of acute hepatitis with jaundice in Italy. The clinical features of the liver injury attributed to high bioavailable forms of curcumin have recently become better defined. The latency to onset of liver injury has varied from a few weeks to as long as eight months but is typically 1 to 4 months. The onset is insidious with fatigue, nausea and poor appetite followed by dark urine and jaundice. Rash and fever are absent or mild. Laboratory tests at onset typically show marked elevations in serum aminotransferase levels (often above 1000 U/L) with only mild increases in alkaline phosphatase. Jaundice occurs if the agent is continued. While signs of hypersensitivity are not prominent, many patients develop autoantibodies and the clinical syndrome and histological features can resemble autoimmune hepatitis. Prednisone has been used to treat severe cases of turmeric hepatotoxicity but is probably not needed as recovery is rapid once the herbal product is discontinued. While reports of acute liver failure has been attributed to turmeric, most cases resolve completely without evidence of chronic injury or bile duct loss. The hepatocellular pattern of injury and frequency of jaundice suggest that fatal instances might occur at a rate of 10% of jaundiced cases, particularly if the product is not discontinued promptly.

Likelihood score: B (likely cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

The acute hepatotoxicity caused by turmeric appears to be due to an idiosyncratic injury, perhaps immunologically mediated. The association with HLA-B*35:01 suggests that the injury is linked to the immune system and perhaps interaction with curcumin or another component of turmeric with the HLA molecule leading to T cell recognition of a self-antigen on liver cells and immune mediated injury. The HLA-B* 35:01 allele is also linked to liver injury due to green tea (Camellia sinensis), Garcinia cambogia, and Polygonum multiflorum (also known as Fo-ti). These 4 herbs all have bioactive constituents that are polyphenols.

Outcome and Management

Most cases of acute hepatic injury from turmeric resolve within 1 to 3 months of stopping the medication. In some instances, however, the injury is severe and unremitting, leading to acute liver failure and either death or need for liver transplantation. A severe outcome is more likely if turmeric is continued after the appearance of symptoms and signs of liver injury. There appears to be no cross sensitivity to hepatic injury between turmeric and other herbal products. However, reexposure to turmeric should be avoided as recurrence and more severe liver injury can occur with rechallenge.

Drug Class: Herbal and Dietary Supplements

CASE REPORTS

Case 1. Acute hepatitis with jaundice attributed to turmeric. Case 3.(1)

A 57 year old woman with recurrent urinary tract infections, migraine headaches, and osteoarthritis developed fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, and anorexia, followed by itching, dark urine, and jaundice. Because of a recurrence of cystitis, she had received a 7-day course of nitrofurantoin 4 months previously and a 7-day course of cephalexin a few weeks previously. Because of persistence of symptoms, she started an over-the-counter preparation of turmeric (Nature’s Way Turmeric, 500 mg once daily) 2 to 3 weeks before onset of symptoms. She had no history of liver disease, did not drink alcohol, and had no risk factors for viral hepatitis. Her other medications included rizatriptan, salbutamol, vitamin C and D, and a multivitamin. On presentation, her serum bilirubin was 9.1 mg/dL, ALT 1425 U/L, AST 1374 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase 250 U/L and she was admitted to a hospital for evaluation. The INR was 1.3 and albumin 3.7 g/dL. Tests for hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. The ANA was positive (1:640), but SMA and AMA were negative and IgG levels were normal (1170 mg/dL). Abdominal ultrasound showed a right renal stone without hydronephrosis and normal appearing liver without evidence of biliary obstruction or gallstones. A liver biopsy showed acute inflammation and necrosis with eosinophils; plasma cells were not prominent and there was no fibrosis. Turmeric had been stopped and her liver tests improved rapidly without specific therapy (see Table). Serum bilirubin levels fell into the normal range within 6 weeks and aminotransferase levels within 3 months of stopping turmeric. When seen in follow up a year after onset, she was asymptomatic, and all liver tests were normal.

Key Points

Laboratory Values

Comment

A middle aged woman developed acute, icteric hepatitis 2 to 3 weeks after starting turmeric for recurrent urinary tract infections that had not responded to nitrofurantoin or cephalosporins. The liver injury began to improve within 1-2 weeks of stopping the turmeric and without other specific therapy. The turmeric product tested positive for curcumin and was negative for other potentially toxic herbal products as well as black pepper. The patient was homozygous for HLA-B*35:01, an HLA allele closely linked to liver injury from several herbal products including turmeric, green tea, Fo-ti, and garcinia. The clinical features of female sex, hepatocellular liver injury, low levels of autoantibodies, lack of rash and fever, and rapid improvement on stopping the product are typical of turmeric induced liver injury. While she had also been exposed to nitrofurantoin and cephalexin, the latency to onset was not compatible with those two antibiotics and cephalexin is a very rare cause of liver injury which is typically cholestatic.

Case 2. Acute hepatitis with jaundice attributed to turmeric. Case 4.(1)

A 35 year old man with chronic low back pain developed fatigue, low grade fever, nausea, vomiting followed by itching, dark urine, and jaundice having taken a dietary supplement of curcumin for the previous two months (Nature’s Lab: Curcumin C3 1,000 mg with BioPerine [black pepper: 5 mg]). He was found to be jaundiced with a total bilirubin of 12.5 mg/dL, ALT 2014 U/L, AST 796 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase 124 U/L (R value 43). His other medications included ibuprofen, “Move Free Joint Support” (glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate and Boswellia), collagen powder, fish oil, vitamins B and C, and a daily multivitamin, all of which he had taken for 9 months or more. He was admitted for evaluation and management. Tests for hepatitis A, B, and C were negative. The ANA was positive (1:160), but SMA and AMA were negative. An ultrasound was normal. Despite discontinuation of the curcumin and treatment with methylprednisolone for 6 days, he remained jaundiced. A liver biopsy showed marked portal and lobular inflammation with lymphocytes and eosinophils but scant plasma cells. He was discharged and followed as an outpatient on antihistamines and cholestyramine for pruritus. Serum enzymes and bilirubin levels gradually decreased and fell into the normal range two months after initial presentation. When seen in follow up 1 year after onset, he was asymptomatic, and all liver tests were normal.

Key Points

Laboratory Values

Comment

A young man started an herbal supplement with high levels of curcumin (1 gram) and black pepper (5 mg) and developed a moderately severe acute hepatitis with jaundice two months later. He had some features of autoimmunity and was treated with methylprednisolone but had little or no response and the corticosteroid was stopped. Eventually he began to improve on his own, symptoms resolved, and liver tests fell into the normal range by 2 months after stopping the supplement. The curcumin product was tested chemically and found to contain both curcumin and black pepper as labelled; no other herbal product or toxin was identified. The patient had some features of autoimmunity (ANA positivity) but the liver biopsy was more compatible with drug induced liver injury, and he didn’t improve during a short trial of corticosteroids. Subsequent testing revealed that he was heterozygous for HLA- B*35:01, an allele strongly associated with hepatic injury caused by herbals that are rich in polyphenols (such as turmeric, green tea, polygonum multiflora, and garcinia).

Case 3. Fatal case of acute liver injury attributed to turmeric. Case 10.(1)

A 62 year old woman developed fatigue and nausea followed by dark urine and jaundice having taken a turmeric root extract (Rite Aid: Turmeric, 500 mg) once daily for wellbeing and arthritis for the previous 14 months. She had no history of liver disease, excessive alcohol intake, or risk factors for viral hepatitis. Her medical conditions included osteoarthritis, season allergies, menopausal symptoms, and uterine fibroids. Her medications included estrogens, pseudoephedrine, diphenhydramine, salbutamol, tramadol, magnesium, fish oil, ginger, glucosamine, vitamins C and D, and a multivitamin, all of which she had taken for more than a year. She stopped the turmeric and 3 days later was seen and found to have abnormal liver tests (bilirubin 2.5 mg/dL, ALT 1230 U/L, AST 1628 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 329 U/L). She was admitted to the hospital briefly. Tests for hepatitis A, B, C and E and for CMV and HSV infection were negative as were routine autoantibody and serum IgG levels. She was discharged and followed as an outpatient, but her condition worsened with bilirubin rising to 13.5 mg/dL and INR to 2.0. She was readmitted. Imaging of the liver showed evidence of diffuse hepatocellular disease, a nodular liver, and ascites. She was listed for emergency liver transplantation but suffered an acute myocardial infarction and ultimately developed multiorgan failure and died one month after initial presentation. An autopsy showed a shrunken liver, massive hepatic necrosis, a ruptured posterior leaflet of the mitral value, and recent myocardial infarction.

Key Points

Laboratory Values

Comment

A 62 year old woman developed a severe acute hepatitis 14 months after starting turmeric. No other cause for the liver injury was identified. The liver injury did not improve with stopping turmeric and within 3 weeks she demonstrated evidence of acute liver failure. She was listed for liver transplantation but developed an acute myocardial infarction and rapidly developed multiorgan failure and died within 5 weeks of onset. Chemical analysis was done on the herbal product which demonstrated the presence of turmeric without black pepper or other potentially hepatotoxins or herbs. The patient was negative for HLA-B*35:01. The case was judged to be only “probable” liver injury due to turmeric. Against the diagnosis was the long latency (greater than a year), lack of improvement with stopping the herbal product, and absence of HLA-B*35:01.

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Turmeric – Generic

DRUG CLASS

Herbal and Dietary Supplements

COMPLETE LABELING

Fact Sheet at National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

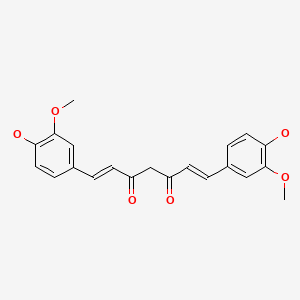

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

CITED REFERENCE

- 1.

- Halegoua-DeMarzio D, Navarro V, Ahmad J, Avula B, Barnhart H, Barritt AS, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury associated with turmeric-a growing problem: ten cases from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network [DILIN]. Am J Med. 2023;136:200-206. [PMC free article: PMC9892270] [PubMed: 36252717]

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 01 June 2024

- Zimmerman HJ. Unconventional drugs. Miscellaneous drugs and diagnostic chemicals. In, Zimmerman, HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott,1999: pp. 731-4.(Expert review of hepatotoxicity published in 1999; turmeric and curcumin are not discussed).

- Seeff L, Stickel F, Navarro VJ. Hepatotoxicity of herbals and dietary supplements. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013, pp. 631-58.(Review of hepatotoxicity of herbal and dietary supplements [HDS]; turmeric and curcumin are not discussed).

- Turmeric. In, PDR for herbal medicines. 4th ed. Montvale, New Jersey: Thomson Healthcare Inc. 2007: pp. 864-7.(Compilation of short monographs on herbal medications and dietary supplements).

- Stedman C. Herbal hepatotoxicity. Semin Liver Dis 2002; 22: 195-206. [PubMed: 12016550](Review and description of patterns of liver injury, including discussion of potential risk factors, and herb-drug interactions; no mention of curcumin).

- De Smet PAGM. Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 2046-56. [PubMed: 12490687](Review of status and difficulties of herbal medications including lack of standardization, federal regulation, contamination, safety, hepatotoxicity, and drug-herb interactions; specific discussion of 4 herbs with therapeutic promise: ginkgo, hawthorn, saw palmetto and St. John’s wort, but not curcumin).

- Schiano TD. Hepatotoxicity and complementary and alternative medicines. Clin Liver Dis 2003; 7: 453-73. [PubMed: 12879994](Comprehensive review of herbal associated hepatotoxicity; curcumin is not listed as causing hepatotoxicity).

- Russo MW, Galanko JA, Shrestha R, Fried MW, Watkins P. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure from drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Liver Transpl 2004; 10: 1018-23. [PubMed: 15390328](Among ~50,000 liver transplants reported to UNOS between 1990 and 2002, 270 [0.5%] were done for drug induced acute liver failure, including 7 [5%] for herbal medications, none attributed to curcumin or turmeric use).

- García-Cortés M, Borraz Y, Lucena MI, Peláez G, Salmerón J, Diago M, Martínez-Sierra MC, et al. [Liver injury induced by “natural remedies”: an analysis of cases submitted to the Spanish Liver Toxicity Registry]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 688-95. Spanish. [PubMed: 19159172](Among 521 cases of drug induced liver injury submitted to a Spanish registry, 13 [2%] were due to herbals, but none were attributed to turmeric or curcumin).

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J; Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1924-34. [PMC free article: PMC3654244] [PubMed: 18955056](Among 300 cases of drug induced liver disease in the US collected between 2004 and 2008, 9% of cases were attributed to herbal medications, but none were linked to turmeric or curcumin use).

- Jacobsson I, Jönsson AK, Gerdén B, Hägg S. Spontaneously reported adverse reactions in association with complementary and alternative medicine substances in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009; 18: 1039-47. [PubMed: 19650152](Review of 778 spontaneous reports of adverse reactions to herbals to Swedish Registry, none of which were attributed to turmeric or curcumin).

- Wongcharoen W, Jai-Aue S, Phrommintikul A, Nawarawong W, Woragidpoonpol S, Tepsuwan T, Sukonthasarn A, et al. Effects of curcuminoids on frequency of acute myocardial infarction after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol 2012; 110: 40-4. [PubMed: 22481014](Among 121 Thai patients who were undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery treated with “curcuminoids” or placebo for 8 days perioperatively, rates of postoperative myocardial infarction were less with curcuminoids [13% vs 30%] as were ALT elevations above 3 times ULN [0% vs 3%]).

- Dulbecco P, Savarino V. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in digestive diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 9256-70. [PMC free article: PMC3882399] [PubMed: 24409053](Review of pharmacokinetics, physical and molecular properties and potential uses of curcumin in digestive diseases; mentions that “as curcumin is particularly concentrated in the human liver, the risk of hepatotoxicity has been closely evaluated, but liver function tests have been shown to be unaffected with doses as high as 2 to 4 g/d”).

- Meng B, Li J, Cao H. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities of curcumin on diabetes mellitus and its complications. Curr Pharm Des 2013; 19: 2101-13. [PubMed: 23116316](Review of the in vivo and in vitro evidence of antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity of curcumin and the rationale for its use in diabetes; “and it has no known side effects”).

- Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 3-17. [PubMed: 23121117](Systematic review of literature on HDS associated liver injury; does not discuss curcumin or turmeric).

- Sanmukhani J, Satodia V, Trivedi J, Patel T, Tiwari D, Panchal B, Goel A, et al. Efficacy and safety of curcumin in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Phytother Res 2014; 28: 579-85. [PubMed: 23832433](Among 60 patients with major depression treated with fluoxetine or curcumin or both for 6 weeks, improvements in depression rating scales were similar in all 3 groups and “there was no significant difference in … laboratory tests … from baseline”).

- Kuptniratsaikul V, Dajpratham P, Taechaarpornkul W, Buntragulpoontawee M, Lukkanapichonchut P, Chootip C, Saengsuwan J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a multicenter study. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9: 451-8. [PMC free article: PMC3964021] [PubMed: 24672232](Among 367 adults with knee osteoarthritis treated with ibuprofen [1.2 g daily] or curcumin extracts [1.5 g daily] for 4 weeks, pain, stiffness and function scores improved equally in both groups and adverse event rates were similar [36% vs 30%]; no mention of ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

- Rahmani S, Asgary S, Askari G, Keshvari M, Hatamipour M, Feizi A, Sahebkar A. Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with curcumin: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res 2016; 30: 1540-8. [PubMed: 27270872](Among 80 Iranian patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease treated with curcumin [500 mg once daily] or placebo for 8 weeks, improvements, as assessed by ultrasonography, were more frequent with curcumin [79% vs 28%], and it was well tolerated with no serious adverse events and mean ALT levels decreased more with curcumin [from 39 to 36 U/L] than placebo [30 to 29 U/L]).

- Panahi Y, Kianpour P, Mohtashami R, Jafari R, Simental-Mendía LE, Sahebkar A. Efficacy and safety of phytosomal curcumin in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2017; 67(4): 244-51. [PubMed: 28158893](Among 102 patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease treated with curcumin [500 mg twice daily] or placebo for 8 weeks, improvements as assessed by hepatic ultrasound were more frequent with curcumin [75% vs 5%] and mean ALT levels fell from 35 to 25 U/L; there were no serious adverse events).

- Mirzaei H, Shakeri A, Rashidi B, Jalili A, Banikazemi Z, Sahebkar A. Phytosomal curcumin: A review of pharmacokinetic, experimental and clinical studies. Biomed Pharmacother 2017; 85: 102-12. [PubMed: 27930973](Review of the chemical characteristics, in vitro antioxidant activity and clinical effects of phytosomal curcumin; mentions that “curcumin is safe and could be tolerated even at very high doses”).

- Nelson KM, Dahlin JL, Bisson J, Graham J, Pauli GF, Walters MA. The essential medicinal chemistry of curcumin. J Med Chem 2017; 60: 1620-37. [PMC free article: PMC5346970] [PubMed: 28074653](Review of the pharmacology and clinical evidence for efficacy of curcumin concludes that the multiple in vitro effects represent assay interference, that it is poorly absorbed and that there is no evidence that it has any effect in humans despite claims for benefit in many conditions including erectile dysfunction, hirsutism, baldness, cancer, and Alzheimer disease).

- Farzaei MH, Zobeiri M, Parvizi F, El-Senduny FF, Marmouzi I, Coy-Barrera E, Naseri R, et al. Curcumin in liver diseases: a systematic review of the cellular mechanisms of oxidative stress and clinical perspective. Nutrients 2018; 10: 855. [PMC free article: PMC6073929] [PubMed: 29966389](Review of the in vitro and in vivo results showing activity of curcumin in decreasing oxidative stress and summary of clinical studies demonstrating efficacy in liver disease).

- Saadati S, Hatami B, Yari Z, Shahrbaf MA, Eghtesad S, Mansour A, Poustchi H, et al. The effects of curcumin supplementation on liver enzymes, lipid profile, glucose homeostasis, and hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 2019; 73: 441-9. [PubMed: 30610213](Among 50 patients with nonalcoholic liver disease given lifestyle advice and either curcumin [1500 mg] or placebo daily for 12 weeks, there were no differences between the two groups in weight loss [-2.4 vs -3.9 kg], changes in ALT [-6 vs -7 U/L] or in controlled attenuation parameter score for hepatic steatosis [-16 vs -32 dB/m]).

- Lukefahr AL, McEvoy S, Alfafara C, Funk JL. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis associated with turmeric dietary supplement use. BMJ Case Rep 2018; 2018: bcr2018224611. [PMC free article: PMC6144106] [PubMed: 30206065](71 year old woman developed serum ALT elevations without jaundice 8-10 months after starting turmeric [ALT ~325 U/L, Alk P, and bilirubin normal; ANA 1:320], which gradually fell into the normal range after stopping).

- Luber RP, Rentsch C, Lontos S, Pope JD, Aung AK, Schneider HG, Kemp W, et al. Turmeric induced liver injury: a report of two cases. Case Reports Hepatol 2019; 2019: 6741213. [PMC free article: PMC6535872] [PubMed: 31214366](A 52year old woman and 55 year old man developed evidence of liver injury 1 and 5 months after starting a turmeric supplement [bilirubin 9.5 and 1.3 mg/dL, ALT 2591 and 1149 U/L, Alk P 263 and 145 U/L], which resolved on stopping and recurred in the first patient on restarting the supplement [bilirubin 3.5 mg/dL, ALT 2093 U/L], which was tested and found free of adulterants).

- Imam Z, Khasawneh M, Jomaa D, Iftikhar H, Sayedahmad Z. Drug induced liver injury attributed to a curcumin supplement. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2019;2019:6029403. [PMC free article: PMC6855017] [PubMed: 31781418](A 78 year old woman with diabetes developed jaundice one month after starting curcumin for hypercholesterolemia [bilirubin 12.8 mg/dL, ALT 609 U/L, Alk P 171 U/L, INR 1.1, ANA 1:320, IgG 951], which resolved on stopping and all liver tests were normal 2 months later).

- Suhail FK, Masood U, Sharma A, John S, Dhamoon A. Turmeric supplement induced hepatotoxicity: a rare complication of a poorly regulated substance. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020; 58: 216-7. [PubMed: 31271321](61 year old woman with polycystic liver disease developed fatigue and dark urine 6 weeks after starting turmeric supplements [bilirubin total 1.6, direct 1.0, ALT 2607 U/L, Alk P 246 U/L, ANA 1:250 normal IgG levels], responding rapidly to a course of prednisone and tests remaining normal after stopping).

- Donelli D, Antonelli M, Firenzuoli F. Considerations about turmeric-associated hepatotoxicity following a series of cases occurred in Italy: is turmeric really a new hepatotoxic substance? Intern Emerg Med 2020; 15: 725-6. [PubMed: 31278559](Letter mentioning an outbreak of acute cholestatic hepatitis in Italy related to use of a turmeric based dietary supplement with high bioavailability, perhaps due to its combination with piperine [black pepper] which increases curcumin absorption).

- Chand S, Hair C, Beswick L. A rare case of turmeric-induced hepatotoxicity. Intern Med J 2020; 50: 258-9. [PubMed: 32037709](62 year old white woman developed fatigue, rash, and jaundice 10 months after starting turmeric [bilirubin >17 mg/dL, ALT 2308 U/L, Alk P not provided, ANA negative, IgG 1670 mg/dL], improving rapidly upon stopping the herbal supplement).

- Nouri-Vaskeh M, Malek Mahdavi A, Afshan H, Alizadeh L, Zarei M. Effect of curcumin supplementation on disease severity in patients with liver cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Phytother Res 2020; 34: 1446-54. [PubMed: 32017253](Among 70 patients with cirrhosis treated with curcumin [1000 mg daily] or placebo for 3 months, those on curcumin had improvements in MELD scores [INR decreasing from 1.57 to 1.49 and bilirubin from 2.5 to 2.1], while those on placebo worsened).

- Lee BS, Bhatia T, Chaya CT, Wen R, Taira MT, Lim BS. Autoimmune hepatitis associated with turmeric consumption. ACG Case Rep J 2020; 7: e00320. [PMC free article: PMC7162126] [PubMed: 32337301](55 year old woman developed jaundice 3 months after starting Quinol Liquid Turmeric [15 mL daily] [bilirubin 11.8 mg/dL, ALT 2743 U/L, Alk P 204 U/L, INR 1.0, ANA 1:80 rising to 1:320], biopsy showing interface hepatitis and plasma cells, and she rapidly improved once turmeric was stopped).

- Lombardi N, Crescioli G, Maggini V, Ippoliti I, Menniti-Ippolito F, Gallo E, Brilli V, et al. Acute liver injury following turmeric use in Tuscany: An analysis of the Italian Phytovigilance database and systematic review of case reports. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2021; 87: 741-53. [PubMed: 32656820](Analysis of the Italian Phytovigilance system identified 37 cases of liver injury attributed to high bioavailability curcumin; 7 cases reported from Tuscany included 6 women and 1 man, ages 45 to 68 years, taking turmeric for 2 weeks to 8 months [bilirubin 6 to 25 mg/dL, ALT 257 to 3303 U/L, GGT 124 to 504 U/L]; follow up after discontinuation was not always available).

- Abdallah MA, Abdalla A, Ellithi M, Abdalla AO, Cunningham AG, Yeddi A, Rajendiran G. Turmeric-associated liver injury. Am J Ther 2020; 27(6): e642-e645. [PubMed: 31283536](51 year old white woman developed jaundice 2 months after starting a turmeric supplement [500 mg daily] [bilirubin total 2.4, direct 0.9 mg/dL, ALT 2484 U/L, Alk P 226 U/L], biopsy showing portal infiltrates including eosinophils, with rapid improvement upon stopping and normal liver tests 8 weeks later).

- Koenig G, Callipari C, Smereck JA. Acute liver injury after long-term herbal "liver cleansing" and "sleep aid" supplement use. J Emerg Med. 2021;60(5):610-614. [PubMed: 33579656](53 year old woman developed jaundice 3-4 weeks after starting 2 herbal supplements, “Liver Detoxifier” which has 16 ingredients including turmeric and “Restful Sleep” with 5 components including valerian and melatonin [bilirubin 25.4 mg/dL, ALT 89 U/L, Alk P 174 U/L, albumin 2.0, INR 1.4], with rapid improvement on stopping).

- Knox C, Bertouch J, Almeida J. Turmeric hepatotoxicity, cause or coincidence? Intern Med J. 2021;51:153. [PubMed: 33572032](Letter in response to Chand [2020] requesting more information about the dose and other ingredients in the turmeric supplement).

- Sohal A, Alhankawi D, Sandhu S, Chintanaboina J. Turmeric-induced hepatotoxicity: report of 2 cases. Int Med Case Rep J. 2021;14:849-852. [PMC free article: PMC8711139] [PubMed: 34992472](Two cases, 57- and 53-year old women developed symptoms of liver injury 3 and ~2 months after starting turmeric [bilirubin 8.6 and 1.8 mg/dL, ALT 1414 and 733 U/L, Alk P not given, INRs normal], resolving within 2 and 1 months of stopping the supplement).

- Sunagawa SW, Houlihan C, Reynolds B, Kjerengtroen S, Murry DJ, Khoury N. Turmeric-associated drug-induced liver injury. ACG Case Rep J. 2022;9:e00941. [PMC free article: PMC9794274] [PubMed: 36600786](49 year old woman developed jaundice 6 weeks after starting turmeric with black pepper [bilirubin 7.1 mg/dL, ALT 3289 U/L, Alk P 138 U/L, INR normal], resolving within 71 days of stopping the supplement).

- Eghbali A, Nourigheimasi S, Ghasemi A, Afzal RR, Ashayeri N, Eghbali A, Khanzadeh S et al. The effects of curcumin on hepatic T2*MRI and liver enzymes in patients with β-thalassemia major: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1284326. [PMC free article: PMC10757948] [PubMed: 38164474](Among 158 patients [above the age of 5] with beta-thalassemia treated with curcumin [500 mg] or placebo twice daily for 6 months, serum ALT levels decreased in those on curcumin [~152 to 105 U/L vs ~152 to 156 U/L], while Alk P levels rose and direct bilirubin levels decreased slightly in both groups; no patient reported any specific side effects from curcumin consumption and “all patients tolerated the capsules well in general.”).

- Halegoua-DeMarzio D, Navarro V, Ahmad J, Avula B, Barnhart H, Barritt AS, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury associated with turmeric-a growing problem: ten cases from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network [DILIN]. Am J Med. 2023;136:200-206. [PMC free article: PMC9892270] [PubMed: 36252717](Ten cases of turmeric-associated liver injury presenting between 2011 and 2022 in the US, all adults [ages 35-71 years], mostly women [80%] and white [90%], with hepatocellular injury [90%], jaundice [50%], and 1 fatality; median ALT 1140 U/L, Alk P 164 U/L, bilirubin 2.5 mg/dL, and a strong association with HLA-B*35:01 [70% vs 12% in controls]).

- Smith DN, Pungwe P, Comer LL, Ajayi TA, Suarez MG. Turmeric-associated liver Injury: a rare case of drug-induced liver injury. Cureus. 2023;15:e36978. [PMC free article: PMC10149439] [PubMed: 37139288](62 year old woman developed jaundice 3 weeks after starting turmeric tea [bilirubin 13.9 mg/dL, ALT 1889 U/L, Alk P 134 U/L, INR normal], with resolution within a month of stopping).

- Ajitkumar A, Mohan G, Ghose M, Yarrarapu S, Afiniwala S. Drug-Induced liver injury secondary to turmeric use. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2023;10:003845. [PMC free article: PMC10187097] [PubMed: 37205206](55 year old woman developed jaundice 1 month after starting 1500 mg of a turmeric supplement daily [bilirubin 8.1 mg/dL, ALT 2143 U/L, Alk P 590 U/L, INR 1.2] who was treated with intravenous N-acetyl cysteine and resolved the injury within 2 months of stopping the supplement).

- Arzallus T, Izagirre A, Castiella A, Torrente S, Garmendia M, Zapata EM. Drug induced autoimmune hepatitis after turmeric intake. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;46:805-806. [PubMed: 36634868](28 year old man developed jaundice 5 months after starting turmeric [bilirubin 7.3 mg/dL, ALT 3770 U/L, Alk P 200 U/L, ANA 1:160, IgG 823 mg/dL, HLA-B*35:01 positive], and treated with prednisone and azathioprine and eventually had normal liver tests apparently off of immunosuppression).

- Foxon F. How prevalent is liver injury attributed to turmeric? Am J Med. 2024;137:e18. [PubMed: 38061832](Letter in response to Halegoua-DeMarzio [2023] suggesting that turmeric-associated liver injury is very rare and not likely to be increasing in frequency, because turmeric has been used for centuries, although not as purified curcumin extracts).

- Haloub K, McNamara E, Yahya RH. An unusual case of dietary-induced liver Injury during pregnancy: a case report of probable liver injury due to high-dose turmeric intake and literature review. Case Reports Hepatol. 2024;2024:6677960. [PMC free article: PMC10864038] [PubMed: 38352658](A pregnant woman developed pruritus during the 23rd week of pregnancy and while taking turmeric [bilirubin 0.2 mg/dL, ALT 734 U/L, Alk P 175 U/L] and improved with stopping turmeric and starting ursodiol, but presented again at 35 weeks with pruritus [bilirubin 0.2 mg/dL, ALT 51 U/L, Alk P 256 U/L, and elevated bile acids], which was interpreted as idiopathic cholestasis of pregnancy and resolved after delivery).

- Alghzawi F, Jones R, Haas C. Turmeric-induced liver injury. J Commun Hosp Intern Med Perspectives. 2024;14:55-59. Not in PubMed.(66 year old African American woman with a recent episode of hepatitis attributed to turmeric, redeveloped jaundice a month after restarting turmeric [bilirubin 29 mg/dL, ALT 738 U/L, Alk P 397 U/L, INR 1.8] with rapid worsening of liver function, hepatorenal syndrome, and death from acute liver failure).

- Carty J, Navarro VJ. Dietary supplement-induced hepatotoxicity: A clinical perspective. J Diet Suppl. 2024:1-20. Epub ahead of print. [PubMed: 38528750](Review of the challenges, diagnosis, and clinical management of liver injury due to HDS including anabolic steroids, aegeline, ashwagandha, ephedra, garcinia, green tea, kratom, and turmeric, mentions that turmeric typically causes hepatocellular injury arising after 1-4 months of therapy).

Publication Details

Publication History

Last Update: June 1, 2024.

Copyright

Publisher

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda (MD)

NLM Citation

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Turmeric. [Updated 2024 Jun 1].