OVERVIEW

Introduction

Triazolam is an orally available benzodiazepine used predominantly for therapy of insomnia. As with most benzodiazepines, triazolam has not been associated with serum aminotransferase or alkaline phosphatase elevations during therapy, and clinically apparent liver injury from triazolam has been reported but is very rare.

Background

Triazolam (trye az" oh lam) is a benzodiazepine that was widely used as a sleeping aid in the therapy of insomnia for several decades but is now rarely used. The soporific activity of the benzodiazepines is mediated by their ability to enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission through binding to the GABA A receptor. Triazolam was approved in the United States in 1982 and rapidly became the most common prescription sleeping pill used in the United States. Concerns over its safety led to its withdrawal from use in the UK, and the availability of other potent, shorter acting sleeping pills has caused its decrease in general use in the United States. Current indications are limited to short-term management of insomnia. Triazolam is available in multiple generic forms and under the brand name Halcion in tablets of 0.125 and 0.25 mg. The recommended initial dose for adults is 0.125 mg immediately before bedtime, increasing to 0.25 as needed; rarely, higher doses are used. The most common side effects of triazolam are dose related and include daytime drowsiness, lethargy, ataxia, dysarthria and dizziness. Tolerance develops to these side effects, but tolerance may also develop to the soporific effects. Triazolam has been linked to complex sleep related behaviors without consciousness, confusion, hallucinations, and with anterograde amnesia, having difficulty forming new memories. Triazolam like all oral benzodiazepines has a boxed warning in its product label stressing (1) the risks of severe sedation and potentially fatal respiratory depression when combined with opiates, (2) with prolonged use, the risks of abuse, misuse, and addiction which can lead to overdose and death, and (3) the risks of dependence with continued use and severe potentially life-threatening withdrawal symptoms if discontinued suddenly. Benzodiazepines are all categorized as Schedule IV controlled substances, having potential for dependence, tolerance, and abuse.

Hepatotoxicity

Triazolam, like other benzodiazepines, is rarely associated with serum ALT and alkaline phosphatase elevations, and clinically apparent liver injury from triazolam is rare. There have been no well described case reports of acute liver injury from triazolam, except for a single report of severe and prolonged cholestatic liver injury ultimately leading to death from hepatic failure. Isolated single cases of clinically apparent cholestatic liver injury have been reported with other benzodiazepines including alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, diazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, and triazolam. The clinical pattern of acute liver injury from benzodiazepines is typically self-limited in course, mild-to-moderate in severity and with a latency of 1 to 6 months. Fever and rash are uncommon as is autoantibody formation.

Likelihood score: D (possible rare cause of clinically apparent liver injury).

Mechanism of Injury

Triazolam is metabolized by the liver to inactive metabolites that are excreted in the urine. Liver injury from benzodiazepines is probably due to a rarely produced intermediate metabolite. The relative safety of triazolam is probably related to its low daily dose (<1 mg).

Outcome and Management

The case reports of hepatic injury due to benzodiazepines were followed by prompt and complete recovery upon stopping the medication, without evidence of residual or chronic injury. A single case of liver failure due to prolonged cholestatic hepatitis after triazolam therapy has been described in the literature. There is no information about cross reactivity with other benzodiazepines, but some degree of cross sensitivity should be assumed.

Drug Class: Sedatives and Hypnotics, Benzodiazepines

CASE REPORT

Case 1. Severe cholestatic liver injury attributed to triazolam.(1)

A 44 year old man developed jaundice approximately 4 months after starting triazolam (0.25 mg nightly) for insomnia which he took 2 to 3 times per week. He had a history of ampullary carcinoma of the pancreas that had been successfully resected 6 years before. A month before the onset of jaundice, he developed atrial fibrillation and was treated with digoxin, hydrochlorothiazide and amiloride. He had no history of liver disease. On presentation, one month after onset of symptoms of jaundice, he was found to have bilirubin of 10.6 mg/dL, AST 97 U/L and Alk P 104 U/L. A percutaneous cholangiogram showed no evidence of biliary obstruction and subsequent laparotomy revealed no cause for the jaundice. A liver biopsy showed intrahepatic cholestasis. He was discharged but continued to worsen and was readmitted several weeks later with progressive hepatic failure. Autopsy showed no biliary obstruction and liver histology again revealed severe intrahepatic cholestasis without cirrhosis.

Comment

Cholestatic hepatitis is typical of the few cases of clinically apparent liver injury that have been linked to benzodiazepine use. The current case, however, is distinctive for the severe and relentless degree of cholestasis. There was no mention of bile duct damage, but the course is not incompatible with rapidly evolving vanishing bile duct syndrome. As stated by the authors, the attribution of the liver injury to triazolam is conjectural. The intermittent use and low doses (less than 1 mg per week) make it an unlikely or only possible cause.

PRODUCT INFORMATION

REPRESENTATIVE TRADE NAMES

Triazolam – Generic, Halcion®

DRUG CLASS

Sedatives and Hypnotics

Product labeling at DailyMed, National Library of Medicine, NIH

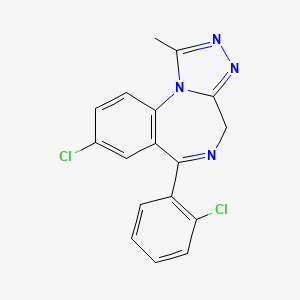

CHEMICAL FORMULA AND STRUCTURE

CITED REFERENCES

- 1.

- Cobden I, Record CO, White RWB. Fatal intrahepatic cholestasis associated with triazolam. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:730–1. [PMC free article: PMC2426204] [PubMed: 6122205]

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

References updated: 24 January 2017

- Zimmerman HJ. Benzodiazepines. Psychotropic and anticonvulsant agents. In, Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1999, pp. 491-3.(Expert review of benzodiazepines and liver injury published in 1999; mentions rare instances of cholestatic hepatitis have been reported due to alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, diazepam, flurazepam, and triazolam, and hepatocellular injury with clorazepate and clotiazepam, but no reports of hepatic injury with lorazepam, oxazepam or temazepam).

- Larrey D, Ripault MP. Anxiolytic agents. Hepatotoxicity of psychotropic drugs and drugs of abuse. In, Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD, eds. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013, p. 455.(Review of drug induced liver injury mentions that rare instances of acute liver injury [usually cholestatic] have been reported with alprazolam, clonazepam, chlordiazepoxide, diazepam, flurazepam and triazolam).

- Mihic SJ, Mayfield J, Harris RA. Hypnotics and sedatives. In, Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, pp. 339-53.(Textbook of pharmacology and therapeutics).

- Cobden I, Record CO, White RWB. Fatal intrahepatic cholestasis associated with triazolam. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:730–1. [PMC free article: PMC2426204] [PubMed: 6122205](44 year old man developed jaundice after 5 months of intermittent triazolam therapy for insomnia [bilirubin 10.6 mg/dL, AST 97 U/L and Alk P 104 U/L]; jaundice deepened and patient died, autopsy showed intrahepatic cholestasis without obstruction or cirrhosis: Case 1).

- Davion T, Capron-Chivrac D, Andrejak M, Capron JP. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1985;9:117–26. [Hepatitis due to antiepileptic agents] [PubMed: 3920108](Review of hepatotoxicity of anticonvulsants; among benzodiazepines, cases of cholestatic hepatitis have been linked to chlordiazepoxide and diazepam, but liver injury from this class of drugs is exceptionally rare).

- Hindmarch I, Fairweather DB, Rombaut N. Adverse events after triazolam substitution. Lancet. 1993;341:55. [PubMed: 8093301](Survey of UK physicians, one year after withdrawal of triazolam in the UK, found higher rate of adverse reactions [largely CNS] with replacements such as temazepam, loprazolam, nitrazepam, and lormetazepam, but no mention of hepatotoxicity).

- Lewis JH, Zimmerman HJ. Drug- and chemical-induced cholestasis. Clin Liver Dis. 1999;3:433–64. vii. Erratum in: Clin Liver Dis 1999; 3: 917. [PubMed: 11291233](Review of drug induced cholestatic syndromes, listing many causes including chlordiazepoxide and flurazepam; “Benzodiazepines may cause cholestatic injury, although this is rare”).

- Sabaté M, Ibáñez L, Pérez E, Vidal X, Buti M, Xiol X, Mas A, et al. Risk of acute liver injury associated with the use of drugs: a multicentre population survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1401–9. [PubMed: 17539979](Among 126 cases of drug induced liver injury seen in Spain between 1993-2000, 20 were attributed to benzodiazepines including 5 for clorazepate, 5 alprazolam, 6 lorazepam and 4 diazepam, but compared to controls, relative risk of injury was increased only for clorazepate [8.3: estimated frequency 3.4 per 100,000 person-year exposures]).

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J., Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924–34. [PMC free article: PMC3654244] [PubMed: 18955056](Among 300 cases of drug induced liver disease in the US collected from 2004 to 2008, none attributed to a benzodiazepine).

- Björnsson E. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiepileptic drugs. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:281–90. [PubMed: 18341684](Review of hepatotoxicity of all anticonvulsants focusing upon phenytoin, valproate, carbamazepine; “furthermore, hepatoxicity has not been convincingly shown to be associated with the use of benzodiazepines”).

- Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM., Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065–76. [PMC free article: PMC3992250] [PubMed: 20949552](Among 1198 patients with acute liver failure enrolled in a US prospective study between 1998 and 2007, 133 were attributed to drug induced liver injury, but none were linked to a benzodiazepine).

- Drugs for insomnia. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2012;10(119):57–60. [PubMed: 22777275](Guidelines for therapy of insomnia mentions that benzodiazepines are controlled substances and when used for sleep may impair next day performance).

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419–25. [PubMed: 23419359](In a population based study of drug induced liver injury from Iceland, 96 cases were identified over a 2 year period, but none were attributed to triazolam or any other benzodiazepine, despite the fact that millions of prescriptions for them are filled yearly).

- Hernández N, Bessone F, Sánchez A, di Pace M, Brahm J, Zapata R, A, Chirino R, et al. Profile of idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury in Latin America. An analysis of published reports. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:231–9. [PubMed: 24552865](Systematic review of literature on drug induced liver injury in Latin American countries published from 1996 to 2012 identified 176 cases, none of which were attributed to a benzodiazepine).

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, Reddy KR, et al. United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1340–1352.e7. [PMC free article: PMC4446235] [PubMed: 25754159](Among 899 cases of drug induced liver injury enrolled in a US prospective study between 2004 and 2013, no cases were attributed to triazolam or any other benzodiazepine).

- Drugs for chronic insomnia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2023;65:1–6. [PubMed: 36630579](Concise review of drugs for chronic insomnia mentions that tolerance and dependence can occur with use of benzodiazepines and their use should be discouraged, and that benzodiazepines are CNS suppressants and can impair next day performance including driving and cause complex behavior disorders, retrograde amnesia, dependence, tolerance, abuse and rebound insomnia; no mention of ALT elevations or hepatotoxicity).

Publication Details

Publication History

Last Update: June 22, 2023.

Copyright

Publisher

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda (MD)

NLM Citation

LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Triazolam. [Updated 2023 Jun 22].