Abbreviations

- AGREE

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation

- ASEPSIS

Additional treatment, Serous discharge, Erythema, Purulent exudate, Separation of the deep tissues, Isolation of bacteria, and duration of inpatient Stay

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- C-section

Caesarean section

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CRD

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

- RCOG

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SIGN

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

Context and Policy Issues

A caesarean section (C-section) is defined as the use of surgery to deliver an infant.1 The procedure involves an incision in the lower abdomen to expose the uterus and a second incision to the uterus to allow removal of the infant and placenta.1 C-section may be performed upon identification of problems that arise during or prior to labour that may put the health of the mother or fetus at risk.1

In 2017, more than 103,000 C-sections were performed in Canada, making it the most common surgical procedure performed in Canadian hospitals.2 Although C-section is generally considered safe, the procedure is not without risks. Wound complications such as infection, hematoma, seroma, and dehiscence are included among the risks of C-section.3 Infection is considered a major potential complication of C-section.3 The risk of wound infection is further elevated among mothers with a body mass index (BMI) above 30 kg/m2.4

Interventions for the care of mothers undergoing C-section target the perinatal period. The focus of this report is the post-surgical period. The specific objectives of this report are to summarize the evidence regarding (1) the clinical effectiveness of removing or replacing surgical dressings at 48 hours following C-section versus other timeframes, (2) the clinical effectiveness of silver-hydrocolloid dressing versus other surgical dressing types applied after C-section, and (3) the evidence-based guidelines regarding post-operative care for surgical wounds following C-section.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness of removing or replacing surgical dressings at 48 hours versus other timeframes following caesarean section?

What is the clinical effectiveness of silver-hydrocolloid surgical dressings versus other surgical dressing types following caesarean section?

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding post-operative care for surgical wounds following caesarean sections?

Key Findings

No relevant evidence regarding the timing of removal or replacement of surgical dressings after caesarean section, or the use of different types of surgical dressings after caesarean section, was identified. One rigorously-developed guideline indicated that no recommendation could be made for or against the routine use of negative pressure dressing therapy, barrier retractors, and subcutaneous trains, for the reduction of wound infection in mothers with a body mass index of ≥30 kg/m2 (based on low- to moderate-quality evidence).4 No guidelines on the use of other types of surgical dressings were identified.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted by an information specialist on key resources including MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Library, the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, the websites of Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. The search strategy was comprised of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concepts were caesarean section and surgical dressings. No filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type for research questions one and two. For research question three, a search filter was applied to limit retrieval to guidelines. The search was also limited to English-language documents published between January 1, 2014 to June 24, 2019.

Selection Criteria and Methods

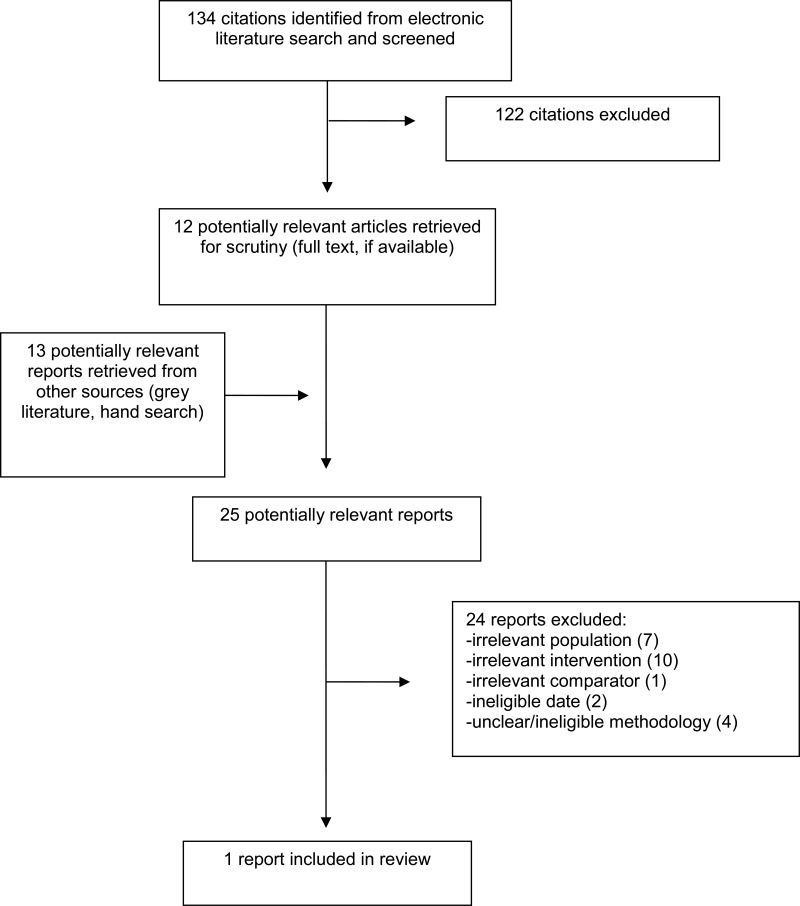

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2014. Guidelines with unclear methodology were also excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included evidence-based guideline was assessed with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument.5 Summary scores were not calculated for the included guideline; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations was described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

A total of 134 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 122 citations were excluded and 12 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Thirteen potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full-text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 24 publications were excluded for various reasons, and one evidence-based guideline met the inclusion criteria and was included in this report. No health technology assessments, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, or non-randomized studies were included. The PRISMA6 flow diagram of the study selection process in presented in Appendix 1. Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Study characteristics are summarized below and details are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

The included guideline was developed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG).4 The guideline development process followed the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence– (NICE) accredited Green-top guideline development process7 and adhered to AGREE II criteria.5 The development committee was composed of research experts, key stakeholders (e.g., clinicians, a patient or lay representative, government representatives), and a methodologist (i.e., NICE representative). Included evidence was critically appraised using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) methodology. The strength of the recommendations and the level of the underlying evidence were rated by guideline leads according to the Green-top guidelines methodology.7 The description of the rating system is described in . Recommendations were agreed to by informal consensus based on discussions. Drafts and final guidelines were circulated for external stakeholder feedback prior to publication.7

Country of Origin

The RCOG guideline was developed for use in the United Kingdom.4

Patient Population

The RCOG guideline was developed for use by clinicians responsible for the care of adults categorized as having obesity according to body mass index (i.e., BMI ≥30 kg/m2) during the perinatal period.4

Interventions and Comparators

The relevant interventions considered within the RCOG guideline were the following post-operative treatments: negative pressure dressing, barrier retractors, and insertion of subcutaneous drains.4

Outcomes

The outcomes considered in the development of the guideline were not explicitly reported, however the relevant recommendation is targeted toward wound healing and infection.4

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Details regarding the strengths and limitations of the included publication are provided in Appendix 3.

The RCOG guideline was critically appraised using the AGREE II instrument.5 Strengths included a clearly defined scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement in the development of recommendations, a rigorous development process, and clear presentation of recommendations.4 One limitation involved the reporting of details related to the development of this specific guideline. Guideline development followed the standardized methodology of the RCOG;7 however, details regarding the specific criteria for selecting the evidence (i.e., the population, interventions, comparators, and outcomes; PICO) for this guideline were not reported. A second notable limitation relates to applicability of the recommendations; considerations for guideline implementation do not appear to have been considered in the development of the guideline or supportive materials.4

Summary of Findings

Clinical Effectiveness of Removing or Replacing Surgical Dressings at 48 Hours following Caesarean Section

No relevant evidence regarding the timing of removal or replacement of wound dressings at 48 hours versus other time intervals following caesarean section was identified; therefore, no summary can be provided.

Clinical Effectiveness of Silver-Hydrocolloid Surgical Dressings following Caesarean Section

No relevant evidence regarding the clinical effectiveness of silver-hydrocolloid surgical dressings versus different surgical dressing types was identified; therefore, no summary can be provided.

Guidelines

One guideline development group did not recommend for or against would care strategies for post-operative care of surgical wounds following C-sections that are specific to mothers with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater.4 The guideline development group indicated that the routine use of negative pressure dressing therapy, barrier retractors, and insertion of subcutaneous drains could not be recommended due to a lack of good quality evidence that these treatments reduce the risk of wound infection in mothers requiring C-sections who have been categorized as having obesity according to BMI (grade of recommendation: B; evidence level ranged from 1+ to 2-).4 No guidelines were identified regarding mothers with a BMI under 30 kg/m2 or on the use of different types of surgical dressings or the timing of their removal or replacement.

Appendix 4 presents a summary of the recommendation in the included guideline.

Limitations

Beyond the few concerns with the methodological quality of the included guideline,4 there were a few limitations associated with this report. First, studies regarding the timing of removal or replacement of surgical dressings post-operation were captured in the search for this report; however, none examined the removal or replacement of dressings at 48-hours post-operation. Second, no comparative clinical evidence regarding the effectiveness of silver-hydrocolloid surgical dressings versus other types of dressings was identified. Third, the recommendations included in the RCOG guideline were developed for use with adults requiring C-section who have a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater; no guidelines were identified to inform the post-operative care of those with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2. Due to an elevated risk of surgical site infection in those with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater,4 it is possible the identified recommendation would not be relevant to populations with a lower BMI. Finally, the RCOG guideline development group consisted of stakeholders including practitioners and government officials located in the United Kingdom.4 Therefore, it is not clear if the evidence would have been similarly interpreted by stakeholders in Canada. As such, the generalizability of recommendations to the Canadian context is not known.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

One evidence-based guideline on wound care following C-section was included in this report.4 No evidence was identified on the clinical effectiveness of removing or replacing surgical dressings at 48-hours post-operation compared to other time intervals, or on the effectiveness of silver-hydrocolloid surgical dressings compared to other types of dressings.

The RCOG guideline includes guidance on C-section wound care in mothers with a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2, based on limited quality evidence.4 Specifically, the RCOG guideline development group could not recommend for or against the routine use of negative pressure dressing therapy, barrier retractors, and subcutaneous trains to reduce the risk of wound infection, citing a lack of good-quality evidence. Future research using high quality study designs may support guideline developers to provide definitive recommendations for or against these treatments. No recommendations addressed different types of surgical dressings or the timing of dressing removal or replacement following C-section. The 2011 NICE guidelines are currently being updated, and it is likely that they will provide comprehensive guidance on a variety of interventions.8

There was a lack of evidence regarding surgical dressing removal or replacement at 48-hours following surgery and comparative effectiveness of different types of surgical dressings identified in this report. Comparative evidence from an RCT9 and a non-randomized study10 provide some insight regarding the timing of dressing removal. Both studies examined the effectiveness of surgical dressing removal at other time intervals (i.e., no comparison with 48-hours post-operation). The RCT showed that there was no difference in incidence of a physician-diagnosed wound complication (i.e., infection, dehiscence, seroma, and hematoma) at five to seven days postpartum in mothers who underwent a planned C-section based who had surgical dressing removal at 24-hours versus six-hours post-surgery.9 Similarly, the non-randomized study showed no difference in self-reported healing problems at six-weeks postpartum between mothers who underwent planned or emergent C-section with surgical dressing removal at post-operative day one, three to four, or seven to eight. Authors of the non-randomized study concluded the timing of dressing removal had no effect on healing problems and recommended adoption of the most convenient protocol.10 However, future comparative research examining dressing removal at 48-hours is needed to ascertain whether those conclusions hold up.

Previous CADTH work of specific relevance to the topic has been conducted. In 2012, a CADTH report examined the clinical evidence and guidelines regarding surgical dressings for the management of C-section wounds in patients classified as overweight and no relevant literature was identified.11 An earlier CADTH report published in 2008 that examined guidelines for C-section wound care in bariatric patients12 identified the 2004 version of the NICE C-section guideline for inclusion.13

References

- 1.

Berghella

V. Patient education: C-section (cesarean delivery) (beyond the basics). In: Post

TW, ed.

UpToDate. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2019:

https://www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2019 Jul 29.

- 2.

- 3.

Berghella

V. Cesarean delivery: postoperative issues. In: Post

TW, ed.

UpToDate. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2019:

www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2019 Jul 29.

- 4.

Denison

FC, Aedla

NR, Keag

O

et al, on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Care of women with obesity in pregnancy: Green-top Guideline No. 72.

BJOG. 2018: 10.1111/1471-0528.15386. Accessed 2019 Jul. 29. [

PubMed: 30465332] [

CrossRef]

- 5.

- 6.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

Peleg

D, Eberstark

E, Warsof

SL, Cohen

N, Ben Shachar

I. Early wound dressing removal after scheduled cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):388.e381–385. [

PubMed: 27018465]

- 10.

Heinemann

N, Solnica

A, Abdelkader

R, et al. Timing of staples and dressing removal after cesarean delivery (the SCARR study).

Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;144(3):283–289. [

PubMed: 30582610]

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publication

Table 2Characteristics of Included Guideline

View in own window

| Intended Users, Target Population | Intervention and Practice Considered | Major Outcomes Considered | Recommendations Development and Evaluation |

|---|

| Denison / RCOG, 20184 |

|---|

Intended users: Clinicians Target population: People with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 during the perinatal period | Post-operative wound care: Negative pressure dressing therapy, barrier retractors, insertion of subcutaneous drains | Wound infection; wound separation | Development process followed the NICE-accredited Green-top Guidelines development process and satisfied the AGREE II criteria7 The Guidelines Committee was composed of:

- -

Clinicians - -

Patient / lay representative - -

Department of Health and Scottish Government representative - -

NICE representative - -

Clinical Effectiveness Team

Evidence Collection, Selection, and Synthesis: A systematic review (searched up to January 2018) was limited to human populations and English language papers; Abstracts and papers were screened by guideline leads Draft developed by informal consensus through discussion; A first, second, and third draft with evidence levels and grades of recommendations were prepared by guideline leads; First, second draft reviewed and checked by Guidelines Committee; Third draft sent and posted for peer-, patient-, and public-review; Draft revised by guideline leads and RCOG; Reviewed by Guidelines Committee; Final guideline approved for publication by Clinical Quality Board Level of evidence “1++ high quality meta analyses, SRs of RCTs, RCTs with low risk of bias 1+ well conducted meta analyses, SRs of RCTs, RCTs with low risk of bias 1- Meta analyses, SRs of RCTs, RCTs with high risk of bias 2++ High quality SRs of case-control or cohort studies, high quality case-control or cohort studies with very low risk of confounding, bias, or chance and high probability the relationship is causal 2+ Well conducted case control or cohort studies with low risk of confounding bias, or chance and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal 2- Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding, bias, or chance, and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal 3 Non-analytical studies 4 Expert opinion”7 (p. 22) Grades of recommendation “A: At least one meta-analysis, SR, or RCT rated as 1++, and directly applicable to target population Or SR of RCTs or body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results B: A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++ directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results; Or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+ C: A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+ directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results; Or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++ D: Evidence level 3 or 4; Or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+”7 (p. 24) |

AGREE II = Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCOG = Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SR = systematic review.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 3Strengths and Limitations of Guidelines using AGREE II5

View in own window

| Item | Guideline |

|---|

| Denison / RCOG, 20184 |

|---|

| Domain 1: Scope and Purpose |

|---|

| 1. The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described. | Yes |

| 2. The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described. | Yes |

| 3. The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described. | Yes |

| Domain 2: Stakeholder Involvement |

|---|

| 4. The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups. | Yes |

| 5. The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought. | Yes |

| 6. The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. | No. It can be assumed that the target users are clinicians involved in the care perinatal care of pregnant people with obesity; however, this was not clearly defined. |

| Domain 3: Rigour of Development |

|---|

| 7. Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. | Yes |

| 8. The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. | No. No information on evidence selection was reported. |

| 9. The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described. | Yes |

| 10. The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. | Yes. |

| 11. The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations. | Yes |

| 12. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. | Yes |

| 13. The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. | Yes |

| 14. A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. | Yes |

| Domain 4: Clarity of Presentation |

|---|

| 15. The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. | Yes |

| 16. The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented. | Yes |

| 17. Key recommendations are easily identifiable. | Yes |

| Domain 5: Applicability |

|---|

| 18. The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application. | No |

| 19. The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice. | No |

| 20. The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. | No |

| 21. The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria. | Yes |

| Domain 6: Editorial Independence |

|---|

| 22. The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline. | Unclear. The guideline and methods document did not report information on the funding of the guideline. |

| 23. Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed. | Yes |

AGREE = Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation; RCOG = Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists.

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Other Intervention – Different Surgical Dressing Types

Connery

SA, Yankowitz

J, Odibo

L, Raitano

O, Nikolic-Dorschel

D, Louis

JM. Effect of using silver nylon dressings to prevent superficial surgical site infection after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019

Jul;221(1):57.e1–57.e7.

PubMed: PM30849351 [

PubMed: 30849351]

Stanirowski

PJ, Bizon

M, Cendrowski

K, Sawicki

W. Randomized controlled trial evaluating dialkylcarbamoyl chloride impregnated dressings for the prevention of surgical site infections in adult women undergoing Cesarean section.

Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2016

Aug;17(4):427–435.

PubMed: PM26891115 [

PMC free article: PMC4960475] [

PubMed: 26891115]

Stanirowski

PJ, Kociszewska

A, Cendrowski

K, Sawicki

W. Dialkylcarbamoyl chloride-impregnated dressing for the prevention of surgical site infection in women undergoing cesarean section: a pilot study.

Arch Med Sci. 2016

Oct

01;12(5):1036–1042.

PubMed: PM27695495 [

PMC free article: PMC5016568] [

PubMed: 27695495]

Dryden

M, Goddard

C, Madadi

A, Heard

M, Saeed

K, Cooke

J. Using antimicrobial Surgihoney to prevent caesarean wound infection. Br J Midwifery. 2014;22(2):111–115.

Other Guidelines – General Surgical Populations

Berríos-Torres

SI, Umscheid

CA, Bratzler

DW, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017

Aug

1;152(8):784–791.

PubMed: PM28467526 [

PubMed: 28467526]

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Post-operative Procedures for Caesarean Sections: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Jul. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.