Context and Policy Issues

Interdisciplinary care is referred to in the literature as an efficient way to provide optimal healthcare services to various population groups, including in the area of perinatal and newborn care.1–4 Although many definitions exist, interdisciplinary care typically involves at least two healthcare professionals of different backgrounds sharing their knowledge and skills in order to set and achieve common objectives for a patient.1,2 The collaborative process requires enhanced communication between service providers, as well as mutual trust and respect in order to share responsibilities.1,2

Interdisciplinary care has been the topic of several CADTH Rapid Response Reports; however, none of these reports evaluated collaborative models of care in a perinatal population of pregnant individuals and newborn infants. According to the World Health Organization, the perinatal period ranges from 22 weeks of pregnancy to 7 days after birth.5 In Canada, there are organizations for whom enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration is recognized as a priority in order to improve the quality and sustainability of healthcare services for parents and infants throughout the perinatal period.1 Assessing the evidence regarding the use of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients will support evidence-based practice decisions to improve health outcomes in these patients.

The purpose of this report is to review the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients in acute care settings.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness regarding the use of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients in acute care settings?

What is the cost-effectiveness regarding the use of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients in acute care settings?

What are the evidence based-guidelines for using interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients in acute care settings?

Key Findings

Two relevant studies regarding the clinical effectiveness of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients in the acute care setting were included: one non-randomized prospective cohort study6 and one retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study.7 No relevant cost-effectiveness evaluations, or evidence-based guidelines, were identified.

Overall, findings from the included studies suggested that a model of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients that includes a dedicated obstetrician collaborating with midwifery care may be associated with a decrease in the percentage of individuals undergoing induction of labour and primary cesarean sections. This collaborative model may also be associated with an increase in the percentage of vaginal births after cesarean delivery.

Uncertainty surrounds these conclusions, as they are drawn from observational studies that may provide lower quality evidence than other study designs. Changes in best clinical practices or patient preferences throughout the study duration, as well as changes in the care model other than interdisciplinary collaboration, may have influenced the findings.

Evidence regarding optimal healthcare services for pregnant individuals and infants during the perinatal period of labour, delivery, and days following birth suggests a potential benefit of using interdisciplinary collaboration of healthcare professionals to improve health outcomes in these patients. High quality clinical and cost-effectiveness research would reduce uncertainty surrounding the true impact of this change in care model on the quality and sustainability of healthcare services. In addition, evidence-based guidelines are needed to indicate the types of collaboration and professional disciplines that would provide optimal benefits for parents and their newborn children.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, CINAHL, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were not applied to limit the retrieval by study type. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2014 and May 9, 2019.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2014. Guidelines that were not evidence-based (i.e. for which the recommendations were not based on a systematic approach to identify and evaluate the supporting evidence) or with unclear methodology were also excluded, as well as position statements and consensus documents that did not describe a formal literature search for evidence upon which the recommendations were based. A list of articles identified from the literature search that did not meet the inclusion criteria is provided in Appendix 5 as additional references of potential interest.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included non-randomized cohort study and the single-group before-and-after study were critically appraised using the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS).8 A review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

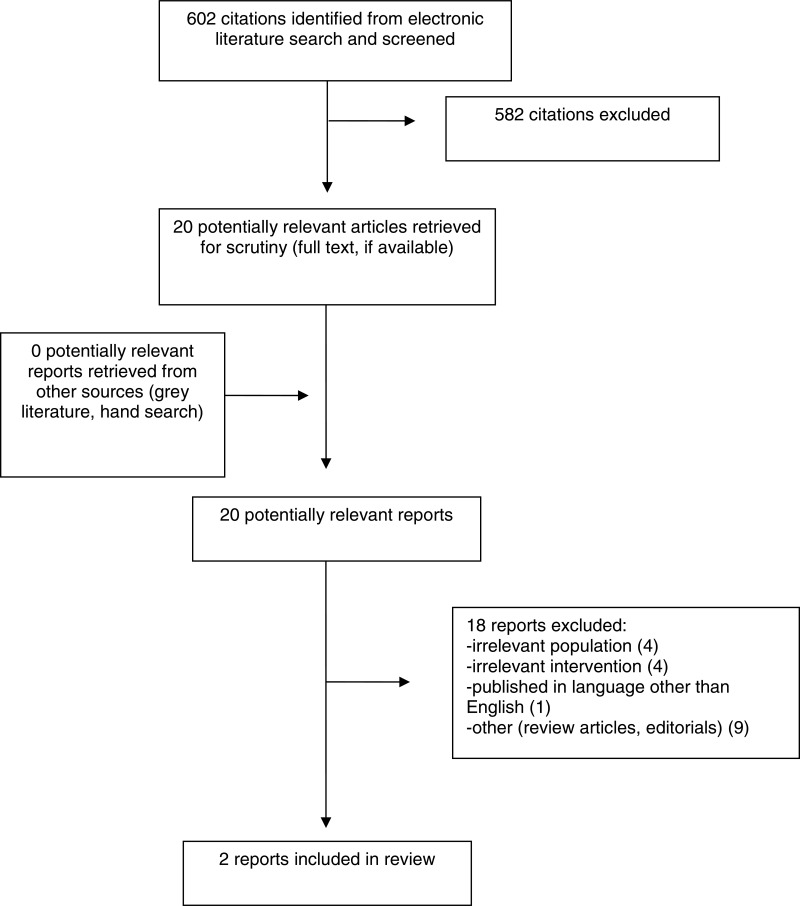

A total of 602 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 582 citations were excluded and 20 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. No potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 18 publications were excluded for various reasons, and 2 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised one non-randomized prospective cohort study and one retrospective uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA9 flowchart of the study selection. Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

A summary of the characteristics of the included clinical studies is provided below. Additional details are available in Appendix 2, .

Study Design

Two clinical studies were included. Rosenstein et al. 20156 was a non-randomized prospective cohort study and Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187 was a retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study.

Country of Origin

The primary authors of the two studies (Rosenstein et al. 20156 and Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) were from the United States.

Patient Population

One study (Rosenstein et al. 20156) included privately insured patients delivering at a community hospital between 2005 and 2014. Publicly insured patients delivering at the same hospital over the same period of time served as a non-equivalent control group due to the fact that they were already offered a collaborative approach from the beginning of the study and therefore, did not undergo any change in care model. The study included 4,884 deliveries (3,413 of these were before the collaborative model was implemented and 1,471 were afterwards). A total of 2,406 participants (49%) were privately insured and as such, were part of the group that experienced a change in care model. The second study (Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) included patients admitted to the obstetrics ward of a mid-sized midwestern medical center. No population characteristics were reported.

Interventions

The two studies (Rosenstein et al. 20156 and Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) evaluated the impact of a collaborative care model that included a labourist and midwifery care. A labourist was generally defined in the studies as a dedicated obstetrician providing labour and delivery management for the obstetrics ward with no or limited competing clinical duties.6,7

Outcomes

Cesarean births as well as vaginal births after cesarean delivery were major clinical outcomes included in both studies. Cesarean births were reported as primary cesarean sections in low-risk nulliparous individuals, and/or as a total number of cesarean sections performed (primary and repeat). Other reported outcomes included induction of labour and composite of short-term adverse neonatal outcomes, which was defined as a 5-minute APGAR < 7, an umbilical artery pH < 7.0 and an umbilical artery base excess > 12. Details regarding the outcome measures used are provided in Appendix 2.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of the included publications are provided in Appendix 3, .

Rosenstein et al. 20156 was a non-randomized prospective cohort study and Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187 was a retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study. Both studies included all patients admitted to the obstetrics ward and delivering at their respective medical center. Data was collected from medical records, a trustworthy source, in a single study center where the majority of healthcare professionals were likely to remain stable throughout the study duration, minimizing potential differences in the way that the routine healthcare services were provided over time. The clinical outcomes included in both studies were objective and assessed by healthcare professionals attending the delivery. Each publication reported results for all major clinical outcomes included in the studies.

Both studies (Rosenstein et al. 20156 and Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187), although relatively well conducted, presented some limitations. More specifically, the non-randomized prospective cohort study (Rosenstein et al. 20156) had a risk of selection bias. The characteristics of privately insured patients differed before and after exposure to the change in care model. A statistically significantly higher proportion of individuals experienced diabetes and hypertension during the period that followed the change in care model compared with the preceding period. In addition, the privately and publicly insured individuals were not comparable population groups as they differed in several of their patient characteristics. However, several relevant characteristics were identified and accounted for in the statistical analysis. The other publication reporting results from a retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study (Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) had insufficient reporting of patient characteristics that precluded assessment of whether the population groups were similar before and after exposure to the change in care model.

Confounders were also a significant issue in both studies. Confounders are factors that may significantly affect the outcome of an observational study by affecting the potential cause and effect relationship of an intervention.8 Before and after differences related to the time elapsed, such as changes in clinical practices or patient preferences throughout the study duration, could not be excluded in both studies and may have influenced the findings. One example is that the authors of Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187 reported that the study’s medical center ceased all early-term inductions and cesarean sections following the release of the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines, which is likely to have some impact on the findings.

The change in care model may also be associated with confounders. In Rosenstein et al. 2015,6 multifactorial changes in the care model included the increased availability of an obstetrician, in addition to the implementation of collaborative care, as patients went from being attended by a private practice physician to a collaboration between a labourist and midwifery care. Although the collaborative care model became available for all privately insured patients, authors reported that the midwifery service attended to a maximum of 42% of the vaginal births among those who were privately insured. This limits exposure to interdisciplinary care and suggests that the increased availability of an obstetrician alone may have had an impact on the findings. In Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187 however, the change in care model was related to the interdisciplinary approach, as patients went from being attended by a labourist only, to a collaboration between a labourist and a certified nurse midwife.

Finally, the patient population was representative of those delivering at the medical centers where the studies were performed. Findings were necessarily affected by the healthcare professionals best practice preferences and by local hospital policies. Therefore, generalizability of the findings to other patient populations is uncertain.

Summary of Findings

A detailed summary of study findings is available in Appendix 4, .

Clinical Effectiveness of Interdisciplinary Care for Maternal and Perinatal Patients

Cesarean Births

Two clinical studies evaluated the impact of a collaborative care model that included a labourist and midwifery care. A labourist was generally defined in the studies as a dedicated obstetrician providing labour and delivery management for the obstetrics ward with no or limited competing clinical duties.6,7

Results from one non-randomized prospective cohort study (Rosenstein et al. 20156) showed a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of pregnant individuals undergoing primary cesarean sections among privately insured patients who experienced a change from private practice to a collaborative care model. No statistically significant difference was observed in cesarean births in those who were publicly insured delivering at the same hospital over the same period of time. These patients were already offered a collaborative approach from the beginning of the study and therefore, did not undergo any change in care model.

Results from one retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study (Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) did not show significant differences in the percentage of pregnant individuals undergoing cesarean sections (primary or total cesarean delivery) between the time period when a labourist only model was in place and after the implementation of a collaborative care model.

Vaginal Births after Cesarean Delivery

Results from one non-randomized prospective cohort study (Rosenstein et al. 20156) showed a statistically significant increase in the percentage of vaginal births after cesarean delivery among privately insured patients who underwent a prior cesarean section between the private practice period and the collaborative care model period. No statistically significant difference was observed in vaginal births after cesarean delivery in those who were publicly insured delivering at the same hospital over the same period of time. These patients were already offered a collaborative approach from the beginning of the study and therefore, did not undergo any change in care model.

Results from one retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study (Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) did not show significant differences in the percentage of vaginal births after cesarean delivery between the labourist only time period and after the implementation of a collaborative care model.

Induction of Labour

Results from one retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study (Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187) showed a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of individuals undergoing induction of labour between the labourist only time period and after the implementation of a collaborative care model.

Composite of Short-Term Adverse Neonatal Outcomes

One non-randomized prospective cohort study (Rosenstein et al. 20156) evaluated a composite of short-term adverse neonatal outcomes, which was defined as a 5-minute APGAR < 7, an umbilical artery pH < 7.0 and an umbilical artery base excess > 12. Results did not show significant differences between the two time periods evaluated in both privately and publicly insured patients. However, the study did not have sufficient power to demonstrate statistical significance for testing of this outcome.

Cost-Effectiveness of Interdisciplinary Care for Maternal and Perinatal Patients

No article regarding the cost-effectiveness of interdisciplinary care for maternal and perinatal patients in acute care settings was identified; therefore, no summary can be provided.

Evidence-Based Guidelines Regarding Interdisciplinary Care for Maternal and Perinatal Patients

No relevant evidence-based guidelines regarding the use of interdisciplinary care for maternal and perinatal patients in acute care settings were identified; therefore, no summary can be provided.

Limitations

This Rapid Response report identified a limited number of relevant studies for inclusion. These were observational studies that may provide lower quality evidence than other study designs such as randomized controlled trials. Therefore, findings should be interpreted with caution.

There was no or limited evidence for various clinical outcomes such as length of hospital stay, neonatal intensive care unit admissions, or perinatal harms outcomes in pregnant individuals and newborn infants.

No Canadian studies were identified. Generalizability of the findings from the included studies to the Canadian population of perinatal patients is uncertain and may vary according to the healthcare professionals best practice preferences and local hospital policies.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Two relevant studies regarding the clinical effectiveness of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients in the acute care setting were included: one non-randomized prospective cohort study6 and one retrospective, uncontrolled single-group before-and-after study.7 No relevant cost-effectiveness evaluations, or evidence-based guidelines, were identified.

Overall, findings from the included studies suggested that a model of interdisciplinary care for perinatal patients that includes a dedicated obstetrician collaborating with midwifery care may be associated with a decrease in the percentage of individuals undergoing induction of labour and primary cesarean sections. This collaborative model may also be associated with an increase in the percentage of vaginal births after cesarean delivery. However, uncertainty surrounds these conclusions, as they are drawn from observational studies that may provide lower quality evidence than other study designs. In addition, confounders were identified that may impact the cause and effect relationship of the interdisciplinary care approach. Changes in best clinical practices or patient preferences throughout the study duration, as well as changes in the care model other than interdisciplinary collaboration, may have influenced the findings.

Evidence regarding optimal healthcare services for pregnant individuals and infants during the perinatal period of labour, delivery and days following birth suggests a potential benefit of using interdisciplinary collaboration of healthcare professionals to improve health outcomes in these patients. High quality clinical and cost-effectiveness research would reduce uncertainty surrounding the true impact of this change in care model on the quality and sustainability of healthcare services. In addition, evidence-based guidelines are needed to indicate the types of collaboration and professional disciplines that would provide optimal benefits for parents and their newborn children.

References

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Harris

SJ, Janssen

PA, Saxell

L, Carty

EA, MacRae

GS, Petersen

KL. Effect of a collaborative interdisciplinary maternity care program on perinatal outcomes.

CMAJ. 2012;184(17):1885–1892. [

PMC free article: PMC3503901] [

PubMed: 22966055]

- 4.

Shamian

J. Interprofessional collaboration, the only way to Save Every Woman and Every Child.

Lancet. 2014;384(9948):e41–42. [

PubMed: 24965821]

- 5.

- 6.

Rosenstein

MG, Nijagal

M, Nakagawa

S, Gregorich

SE, Kuppermann

M. The association of expanded access to a collaborative midwifery and laborist model with cesarean delivery rates.

Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):716–723. [

PMC free article: PMC4580519] [

PubMed: 26348175]

- 7.

Krolikowski-Ulmer

K, Watson

TJ, Westhoff

EM, Ashmore

SL, Thompson

PA, Landeen

LB. The collaborative laborist and midwifery model: an accepted and sustainable model.

S D Med. 2018;71(12):534–537. [

PubMed: 30835985]

- 8.

Kim

SY, Park

JE, Lee

YJ, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(4):408–414. [

PubMed: 23337781]

- 9.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Clinical Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Interventions | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Non-Randomized Cohort Study |

|---|

Rosenstein et al. 20156

US | Prospective cohort study.

Data collected prespectively by delivering clinicians and nurses and by three dedicated chart abstractors. | Privately insured patients who delivered at one community hospital. Publicly insured patients whose care model did not change served as a non-equivalent control group.

N = 4,884 deliveries included (3,413 before the model change and 1,471 after).

N=3,560 womena nulliparous with term, singletons in the vertex position.

N=1,324 women had a prior cesarean.

N=2,406 women privately insured (49% of all deliveries). | Collaborative model including a labourist and midwifery care.

Labourist was defined as an obstetrician providing labour and delivery coverage without competing clinical duties. | Clinical outcomes:

Primary cesarean rates among nulliparous women carrying term, singleton pregnancies in the vertex position Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery rates among women with a history of prior cesarean Composite of short-term adverse neonatal outcomes

Follow-up time points:

|

| Uncontrolled, Single-Group Before-and-After Study |

|---|

Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187

US | Retrospective single-arm before-and-after study.

Data for clinical outcomes obtained from electronic medical records. | Patients admitted to the obstetric ward of one midsized midwestern medical center performing approximately 3,000 deliveries / year.

No additional population characteristics were reported. | Collaborative obstetric model including a labourist and a certified nurse midwife. Labourist defined as dedicated obstetrician overseeing the management of labour and performing deliveries as primary physician or consultant. | Clinical outcomes:

Rates of induction of labour Total (primary and repeat) cesarean sections Vaginal births after cesarean section Staff satisfaction

Relevant follow-up time points:

|

- a

Recognizing that there is a spectrum of gender identities, the word women is used here to reflect the language used in the study.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 3Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Studies using RoBANS8

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Non-Randomized Cohort Study: Rosenstein et al. 20156 |

|---|

Target group selection

Confounders

Data collected from only one hospital group, with the majority of healthcare professionals likely to remain stable throughout the study duration. Several potential confounders were identified and accounted for in the statistical analysis (adjusted odds ratios).

Exposure measurement

Data collected from medical records, a trustworthy source, by healthcare providers and dedicated chart abstractors. Therefore, risk of performance bias considered low.

Blinding of assessors

Outcome assessment

Clinical outcomes were objective. Outcome assessment by healthcare professionals handled in a trustworthy manner. Therefore, risk of confirmation bias considered low.

Completeness of outcome data and outcome reporting

Expected major clinical outcomes included in the study with results reported in the publication. Patient discontinuation or missing data unlikely considering the nature of the event (i.e. delivery). Therefore, risk of attrition and reporting bias considered low.

| Target group selection and comparison

Confounders

Before and after differences related to the time elapsed, such as changes in best clinical practices or patient preferences throughout the 10-year study duration, cannot be excluded and may have influenced findings from the clinical outcomes. Multifactorial change in care model including the increased availability of an obstetrician, in addition to implementation of collaborative care (from private practice to collaboration between labourist and midwifery care). Although the collaborative care model became available for all privately insured women, authors reported that the midwifery service attended to a maximum of 42% of the vaginal births among those who were privately insured.

Generalizability

Patient population representative of one medical center, healthcare professionals best practice preferences and hospital policies. Generalizability of the findings to other patient populations is unknown.

|

| Uncontrolled, Single-Group Before-and-After Study: Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187 |

|---|

Target group selection

Confounders

Data collected from only one hospital group, with the majority of healthcare professionals remaining the same throughout the study duration. Change in care model related to interdisciplinary care approach (from labourist only to collaboration between labourist and certified nurse midwife).

Exposure measurement

Data collected from medical records, a trustworthy source. Healthcare provider responsible for medical records update, checked by coordinator and director. Therefore, risk of performance bias considered low.

Outcome assessment

Clinical outcomes were objective. Outcome assessment by healthcare professionals handled in a trustworthy manner. Therefore, risk of confirmation bias considered low.

Completeness of outcome data and outcome reporting

Expected major clinical outcomes included in the study with results reported in the publication. Patient discontinuation or missing data unlikely considering the nature of the event (i.e. delivery). Therefore, risk of attrition and reporting bias considered low.

| Target group selection and comparison

Insufficient reporting of patient characteristics precluded assessment of whether the population groups were similar before and after exposure to the change in care model. Data was collected retrospectively.

Confounders

Before and after differences related to the time elapsed could not be excluded and may have influenced findings from the clinical outcomes. Authors reported that the study’s medical center ceased all early-term inductions and cesarean sections following the release of the 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines. Potential confounders were not accounted for in the statistical analysis.

Generalizability

Patient population representative of one medical center, healthcare professionals best practice preferences and hospital policies. Generalizability of the findings to other patient populations is unknown.

|

- a

Recognizing that there is a spectrum of gender identities, the word women is used here to reflect the language used in the study.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 4Summary of Findings of Included Clinical Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Non-Randomized Cohort Study: Rosenstein et al. 20156 |

|---|

| Clinical Outcomes | Privately Insured patients (Intervention) | Publicly Insured Patients (Control) | “[…] the expansion of midwifery and laborist services in a collaborative practice model at a single community hospital was associated with a decreased primary cesarean delivery rate and an increased rate of VBAC” (p 6) |

|---|

| Private Practice Model | Collaborative Model | P value | Before | After | P value |

|---|

| Primary cesarean sections |

|---|

| n/N (%) | 381/1201 (31.7) | 130/521 (25.0) | P = 0.005 | 208/1340 (15.5) | 80/498 (16.1) | P = 0.78 |

| OR* (95% CI) | 0.56 (0.39–0.81) | P = 0.002 | 0.80 (0.54–1.17) | P = 0.25 |

| Vaginal births after cesarean section |

|---|

| n/N (%) | 60/452 (13.3) | 52/232 (22.4) | P = 0.002 | 142/420 (33.8) | 59/220 (26.8) | P = 0.07 |

| OR* (95% CI) | 2.03 (1.08–3.80) | P = 0.03 | 0.74 (0.41–1.36) | P = 0.34 |

Composite of short-term adverse neonatal outcomes

(5 minute APGAR <7, umbilical artery pH<7.0, umbilical artery base excess >12) |

|---|

| n/N (%) | 21/1649 (1.3) | 17/749 (2.3) | P = 0.07 | 47/420 (2.7) | 18/220 (2.5) | P = 0.84 |

| OR* (95% CI) | 1.47 (0.57–3.75) | P = 0.42 | 0.72 (0.30–1.71) | P = 0.45 |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

* Adjusted for maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, gestational age, epidural, induction of labour, maternal medical complication, birth weight, delivery year, and with an interaction term for insurance type. |

| Uncontrolled, Single-Group Before-and-After Study: Krolikowski-Ulmer et al. 20187 |

|---|

| Clinical Outcomes, Percentage of events (95% CI) | Labourist Only Period (from 2011 to 2013) | Collaborative Period (from 2014 to 2016) | “[…] a collaborative care model on the obstetric floor at this Institution has had a positive impact on patient care outcomes and staff satisfaction.” (p 534) |

|---|

| Induction of labour | 46.5 (45.5 to 47.5) | 28.9 (27.9 to 29.8) |

| Primary cesarean sections | 14.6 (14.0 to 15.3) | 13.7 (13.0 to 14.4) |

| Total (primary and repeat) cesarean sections | 28.5 (27.6 to 29.4) | 27.8 (26.9 to 28.7) |

| Vaginal births after cesarean section | 12.9 (11.4 to 14.6) | 15.1 (13.4 to 16.9) |

| CI = confidence interval. |

VBAC = vaginal births after cesarean section.

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Toolkits and Frameworks Regarding Implementation of Interdisciplinary Care for Pregnant and/or Perinatal Patients

Renfrew

MJ, McFadden

A, Bastos

MH, et al

Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care.

Lancet. 2014

Sep

20;384(9948):1129–1145. [

PubMed: 24965816]

Qualitative Evidence Regarding Interdisciplinary Care for Pregnant and/or Perinatal Patients

Baldwin

A, Harvey

C, Willis

E, Ferguson

B, Capper

T. Transitioning across professional boundaries in midwifery models of care: A literature review.

Women Birth. 2018

Aug

22. pii: S1871-5192(18)30264-6. [

PubMed: 30145166]

Macdonald

D, Snelgrove-Clarke

E, Campbell-Yeo

M, Aston

M, Helwig

M, Baker

KA. The experiences of midwives and nurses collaborating to provide birthing care: a systematic review.

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015

Nov;13(11):74–127. [

PubMed: 26657466]

Interdisciplinary Training Programs for Pregnant and/or Perinatal Patients

Meeker

K, Brown

SK, Lamping

M, Moyer

MR, Dienger

MJ. A high-fidelity human patient simulation initiative to enhance communication and teamwork among a maternity care team.

Nurs Womens Health. 2018

Dec;22(6):454–462. [

PubMed: 30389279]

Olander

E, Coates

R, Brook

J, Ayers

S, Salmon

D. A multi-method evaluation of interprofessional education for healthcare professionals caring for women during and after pregnancy.

J Interprof Care. 2018

Jul;32(4):509–512. [

PubMed: 29424573]

Kumar

A, Sturrock

S, Wallace

EM, et al. Evaluation of learning from Practical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training and its impact on patient outcomes in Australia using Kirkpatrick’s framework: a mixed methods study.

BMJ Open. 2018

Feb

17;8(2):e017451. [

PMC free article: PMC5855459] [

PubMed: 29455162]

Eddy

K, Jordan

Z, Stephenson

M. Health professionals’ experience of teamwork education in acute hospital settings: a systematic review of qualitative literature.

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016

Apr;14(4):96–137. [

PubMed: 27532314]

Baird

SM, Graves

CR. REACT: an interprofessional education and safety program to recognize and manage the compromised obstetric patient.

J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2015

Apr-Jun;29(2):138–148. [

PubMed: 25919604]

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Interdisciplinary care approach for perinatal patients in acute care settings: Clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Jun. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.