Abbreviations

- CCS

Canadian Cardiovascular Society

- CHF

Chronic heart failure

- CSS KCCQ

Clinical summary score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- mg

Milligrams

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- OSS KCCQ

Overall summary score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RHR

Resting heart rate

- SD

Standard deviation

- SR

Systematic review

Context and Policy Issues

Heart failure has been defined as “a complex clinical syndrome in which abnormal heart function results in, or increases the subsequent risk of, clinical symptoms and signs of reduced cardiac output and/or pulmonary or systemic congestion at rest or with stress. […] Chronic heart failure (CHF) is the preferred term representing the persistent and progressive nature of the disease.”1 Stable CHF is difficult to define, given that patients frequently deteriorate and are at risk of acute events.1

There are over 660,000 people living with heart failure in Canada and over 90,000 new cases diagnosed every year in Canada according to 2012/13 data.2 Both decreasing left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and functional capacity (as characterized by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification)3 have been associated with higher mortality.4,5

Ivabradine was approved by Health Canada in 2017 for the treatment of chronic heart failure (CHF) for patients with an ejection fraction of less than or equal to 35%, heart rate of 77 or greater, and NYHA classification II or III.6 Guidelines have endorsed ivabradine for treatment of patients with CHF and LVEF of less than or equal to 35%.7,8 One large trial used and supported the 35% threshold.9

Recently published guidelines suggested use of ivabradine in patients with ejection fractions of less than or equal to 40%.1,10 To inform decision making about use of ivabradine in an expanded population, a review was conducted to assess the current literature.

The CADTH Common Drug Review Report for Lancora (ivabradine)11 assessed the evidence for the use of ivabradine in patients with LVEF of <35%. This review (Rapid Response Summary with Critical Appraisal) is an upgrade to a CADTH Rapid Response Summary of Abstracts, which assessed the clinical effectiveness of ivabradine for adults with stable CHF12 and LVEF >35% and ≤40%. This report expands on the Summary of Abstracts by reviewing and assessing full text articles.

Research Question

What is the clinical effectiveness of ivabradine for patients with stable chronic heart failure and with left ventricular ejection fraction > 35% and ≤ 40%?

Key Findings

There were no studies identified with inclusion criteria of patients with stable chronic heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 35% and less than or equal to 40% Two studies, however, included patients with LVEF less than 40% and were included because the mean LVEF was greater than 35% and less than or equal to 40%. One study was a randomized controlled trial comparing ivabradine plus carvedilol to carvedilol. The second study was a non-randomized study, also comparing ivabradine plus carvedilol to carvedilol. Patients in the ivabradine groups demonstrated improvement in numerous outcomes, including resting and mean heart rate reduction, New York Heart Association classification, quality of life outcomes, and left ventricular ejection fraction.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

This report used the same literature search as the previous Rapid Response report (summary of abstracts) conducted on the same topic.12

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including Medline via OVID, the Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. No filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2014 and March 7, 2019.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened the full-text articles of the references included in the Rapid Response Summary of Abstracts to assess for inclusion. As the Summary of Abstracts report includes articles based on the information contained within the abstract, and not full text review, full texts were retrieved to confirm inclusion. The titles and the abstracts in the appendix of the Rapid Response Summary of Abstracts12 were also screened. Using the full literature search described above, the one reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2014. Studies with a mean left ventricular ejection fraction of <35% were excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The randomized studies were critically appraised using the Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials from the Joanna Briggs Institute,13 non-randomized studies were critically appraised using the Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (non-randomized experimental studies).13 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

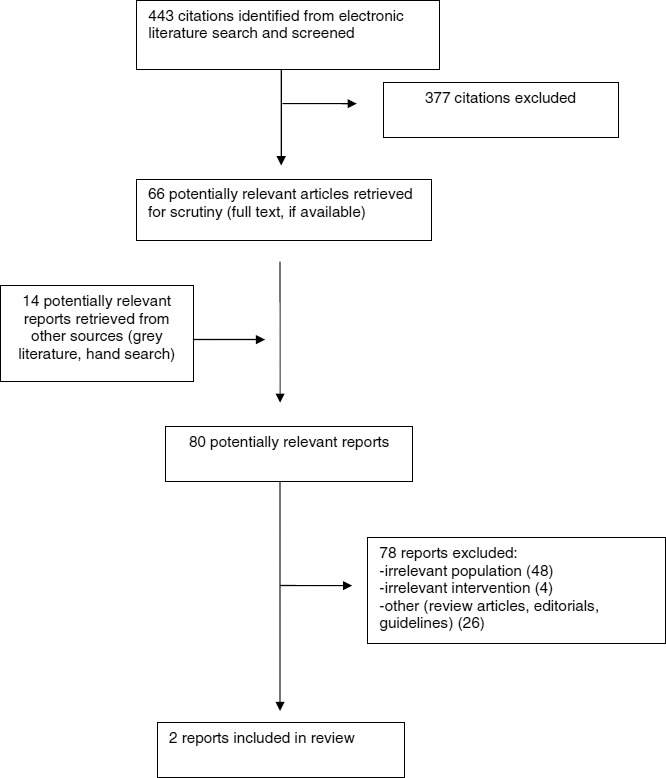

A total of 443 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 377 citations were excluded and 66 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full text review. An additional 14 potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of these 80 potentially relevant articles, 78 publications were excluded for various reasons, and two publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA14 flowchart of the study selection. Appendix 5 reports trials that included patients with LVEF of less than 40%. These trials were not limited to those with LVEF over 35% and less than or equal to 40%, and therefore were not included in this review.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Study Design

Two primary studies were included in this review, one was a randomized controlled trial (RCT)15 and the other was a non-randomized study.16 The RCT was also included in the previous Rapid Response Summary of Abstracts. The non-randomized study was included in the appendix of the previous Summary of Abstracts; upon full-text review it was deemed eligible. One other study was included in the Rapid Response Summary of Abstracts but was deemed ineligible for the current review once the full text article was reviewed.

Country of Origin

The RCT was conducted in Oman.15 The non-randomized study was conducted in Ukraine.16

Patient Population

The RCT was conducted in an out-patient setting.15 The mean age and standard deviation (SD) was 65±10 years in the comparator group and 62±9.2 in the intervention group. Males comprised 70% of the whole group. The mean LVEF and SD was 37±16% in the intervention group and 38±15% in the comparator group. The intervention and comparator group were similar in most characteristics; however, the intervention group had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes or hyperlipidemia, and a higher reported incidence of previous myocardial infarction compared to the comparator group. The intervention group also had a significantly higher NYHA classification (2.6±0.5) compared to the comparator group (1.6±1.5). The reporting of the NYHA classification is unclear, and is likely a mean and standard deviation, which indicates that some patients in the study may have NYHA classification outside of the classification of interest. The two quality of life scores, at baseline were not significantly different in the two groups.

The non-randomized study was also conducted in an out-patient setting.16 The patients had a mean age of 62.9 years and 67% were male. Mean LVEF for the whole sample was 37.0 ± 5.9% (SD). The intervention and comparator group were similar in most characteristics. The proportion of patients in NYHA classification II were similar in both groups (39% in the intervention group and 42% in the comparator group) and the distance covered in the sixminute walk test was also similar in the two groups (458±93.2 metres SD in the intervention group compared to 465.3 ± 87.6 metres SD in the comparator group).

Interventions and Comparators

In the randomized controlled trial, patients in the intervention group were given both carvedilol and ivabradine, starting at 3.125 milligrams (mg) and 2.5.mg respectively, both twice a day and increased up to 25 mg for carvedilol and 7.5 mg ivabradine.15 The comparator group received carvedilol starting at a dose of 3.125 mg twice a day, and increased up to 25 mg twice a day.

In the non-randomized study, all patients were given 3.125 mg carvedilol and increased up to 25 mg as tolerated.16 Those patients in the intervention arm were given 5 mg ivabradine twice a day and increased up to 7.5 mg twice a day as tolerated.

In both studies, the patients were followed closely to achieve optimal heart rate and monitor for adverse events such as bradycardia.

Outcomes

The included RCT reported data on heart rate reduction and echocardiographic changes including LVEF, and quality of life using the Overall Summary Score of the of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (OSS KCCQ) and the Clinical Summary Score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (CSS KCCQ).15 Data was collected at baseline and at 12 weeks post randomization.

The non-randomized study reported data on heart rate reduction, exercise tolerance, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and heart function measures by echocardiogram.16 Data was collected at baseline and five months after participating in the study.

Additional details regarding the characteristics of the included studies are provided in Appendix 2.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

The RCT was not clear about allocation concealment, blinding, and numbers of patients with complete follow-up for all the outcome measures.15 The RCT included multiple echocardiographic measures, which could have led to a higher chance of finding a difference. Also, worth noting is the baseline imbalances in hypertension, diabetes or hyperlipidemia, and a higher reported incidence of previous myocardial infarction and a higher mean NYHA classification were all present in the intervention group despite randomization. The authors for this paper appear to report mean NYHA classification, as opposed to the number of patients within each classification. It is unclear how many patients were within each classification and how many were not in NYHA classification II or III.

The non-randomized study did not address whether subject could be receiving other treatments which could affect the outcomes. There is a chance of imbalance given the nonrandom nature of group assignment. There were no attempts reported to improve reliability in the testing by perhaps, performing the more subjective tests such as six minute walk test on two separate days for each patient. The allocation procedure is also subject to bias. The choice to treat with ivabradine was left to the discretion of the investigator. Given the baseline data presented, there does not seem to be a clear imbalance.

Both studies had relatively small sample sizes (100 patients in the RCT and 69 patients in the non-randomized study) making inferences to large populations difficult. Both had relatively short times to follow-up, five months or less. Although they did report adverse events, there is not enough data to make conclusions about mortality or serious adverse events. It is not clear how many patients were in that range of interest with an LVEF greater than 35% and less than or equal to 40%.

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 3.

Summary of Findings

Appendix 4 presents a table of the main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

The included RCT found a statistically significant improvement at 12 weeks in NYHA classification (P = 0.047), CSS KCCQ (P = 0.002), OSS KCCQ (P = 0.001), and lower resting heart rate (P = 0.002) in the ivabradine group plus carvedilol compared with the carvedilol group.15 There was an improvement in LVEF in the ivabradine plus carvedilol compared to the carvedilol group but the differences between the groups did not reach statistical significance. There were more adverse events in the ivabradine group; the ivabradine plus carvedilol had five patients with symptomatic bradycardia, three patients with asymptomatic bradycardia, two patients with hypotension, and three patients each with palpitations or phosphenes. The carvedilol group had one patient with asymptomatic bradycardia, one patient with hypotension and three with palpitations and no patients with symptomatic bradycardia or phosphenes. None of the differences between individual adverse events reached statistical significance.

Similarly, the non-randomized trial demonstrated a statistically significant improvement over five months with a decrease resting heart rate (P < 0.001), and more distance covered in the six minute walking test performance (P < 0.001), and more patients improved in NYHA classification in the ivabradine plus carvedilol group compared with the carvedilol group (P < 0.05). The systolic blood pressure was lower in the carvedilol group compared to the ivabradine plus carvedilol group (P < 0.001). There was an improvement in LVEF in the ivabradine plus carvedilol compared to the carvedilol group; the difference in the LVEF was not statistically significant at 5 months, but the increase in LVEF from baseline was significantly greater in the ivabradine plus carvedilol group compared to the carvedilol group (P < 0.001). The adverse events were considered mild; in the ivabradine plus carvedilol group, three patients developed mild bradycardia, but no syncope or serious electrocardiogram abnormalities and two patients had mild episodes of visual blurring. In the carvedilol group six patients developed muscle weakness or general weakness and two patients had a transient bronchial obstruction.

Limitations

This review has limitations which should be considered when reviewing this evidence. No studies were identified including only patients with LVEF of greater than 35% and less than or equal to 40%. Because studies were included if the mean LVEF was greater than 35% and less than or equal to 40%, there were patients included who had LVEF less than 35%. The RCT did not report the number of patients in each NYHA classification, and the mean values of NYHA reported at baseline suggest that some patients are in NYHA class I.

The search was done for studies published after 2014, and therefore additional studies may have been identified with a longer search period.

The two studies were small in size (100 or less patients in both) and therefore may limit the generalizability of the findings. The follow-up time periods were five months or less and the adverse event rate with the short follow-up time periods support the need for trials with longer time periods. The two included studies were not designed to assess the outcomes of morbidity and mortality, which are common clinical outcomes in the CHF population.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Although the Health Canada approved indication for ivabradine is for patients with LVEF of less than or equal to 35%, one guideline suggests considering treating patients with CHF and LVEF less than or equal to 40%,1 and another presents the same recommendation for those with LVEF of less than 40%10 (Appendix 5). There was limited information identified to address the question about the use of ivabradine in those with LVEF greater than 35% and less than or equal to 40%.

Two studies were identified that addressed the question about the effect of ivabradine on clinical outcomes in this expanded population (LVEF >35% and ≤40%). Both studies showed positive effects but have limitations. Improvements were reported for the following outcomes: NYHA classification, quality of life, resting heart rate, and six-minute walking test performance. Adverse events were reported in both studies in treatment and comparator groups. Although the information identified for the use of ivabradine in the expanded population was limited, the findings were generally positive in favor of ivabradine. Additional studies including the expanded population may be required to inform practice change.

References

- 1.

Ezekowitz

JA, O’Meara

E, McDonald

MA, et al. 2017

comprehensive update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of heart failure.

Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(11):1342–1433. [

PubMed: 29111106]

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

Solomon

SD, Anavekar

N, Skali

H, et al. Influence of ejection fraction on cardiovascular outcomes in a broad spectrum of heart failure patients.

Circulation. 2005;112(24):3738–3744. [

PubMed: 16330684]

- 5.

Ahmed

A, Aronow

WS, Fleg

JL. Higher New York Heart Association classes and increased mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular function.

Am Heart J. 2006;151(2):444–450. [

PMC free article: PMC2771182] [

PubMed: 16442912]

- 6.

- 7.

Yancy

CW, Jessup

M, Bozkurt

B, et al. 2017

ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America.

Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137–e161. [

PubMed: 28455343]

- 8.

- 9.

Swedberg

K, Komajda

M, Bohm

M, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study.

Lancet. 2010;376(9744):875–885. [

PubMed: 20801500]

- 10.

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

Tufanaru

C, Munn

Z, Aromataris

E, Campbell

J. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris

E, Munn

Z, eds. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual.: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- 14.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 15.

Sallam

M, Al-Saadi

T, Alshekaili

L, Al-Zakwani

I. Impact of ivabradine on health-related quality of life of patients with ischaemic chronic heart failure.

Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2016;14(5):481–486. [

PubMed: 27145825]

- 16.

Bagriy

AE, Schukina

EV, Samoilova

OV, et al. Addition of ivabradine to beta-blocker improves exercise capacity in systolic heart failure patients in a prospective, open-label study.

Adv Ther. 2015;32(2):108–119. [

PubMed: 25700807]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Primary Clinical Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Sallam et al. 2016, Oman15 | Randomized controlled trial | Data presented as percent or mean ± standard deviation. | Intervention group: Carvedilol 3.125 mg b.i.d., increasing to 25 mg b.i.d.; Ivabradine, 2.5 mg b.i.d., increasing to a maximum dose of 7.5 mg b.i.d Comparator group: Carvedilol, 3.125 mg b.i.d. increasing to a maximum dose 25 mg b.i.d. | Quality of life measures (CSS KCCQ, OSS KCCQ), NYHA classification, echocardiograph ic measures, resting and mean heart rate. 12 weeks followup |

| Ivabradine and Carvedilol | Carvedilol | Significance |

|---|

| Age (years) | 62±9.2 | 65±10 | NS |

|---|

| Male (%) | 66% | 74% | NS |

|---|

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28±7.1 | 27±4.0 | NS |

|---|

| Hypertension (%) | 70% | 42% | P = 0.005 |

|---|

| DiabetesMellitus (%) | 66% | 36% | P = 0.003 |

|---|

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 54% | 26% | P = 0.004 |

|---|

| Previous MI (%) | 84% | 48% | P < 0.001 |

|---|

| RHR(beats/minute) | 79±12 | 80±16 | NS |

|---|

| Mean heart rate (beats/minute) | 82±13 | 81±11 | NS |

|---|

| NYHA classification (mean) | 2.6±0.5 | 1.6±1.5 | P = 0.001 |

|---|

| LVEF(%) | 37±16 | 38±15 | NS |

|---|

| CSS KCCQ (score) | 63±19 | 63±21 | NS |

|---|

| OSS KCCQ (score) | 62±19 | 59±21 | NS |

|---|

| Bagriy 2015, Ukraine16 | Prospective, open-label non-randomized study | Data presented as percentage or mean ± standard deviation. | Intervention group: Carvedilol 3.125 mg b.i.d., increasing to 25 mg b.i.d.; Ivabradine, 2.5 mg b.i.d., increasing to a maximum dose of 7.5 mg b.i.d. Comparator group: Carvedilol, 3.125 mg b.i.d. increasing to a maximum dose 25 mg b.i.d. | RHR, Exercise tolerance, SBP, DBP, and heart function measures by echocardiogram. Five-months follow-up |

| Ivabradine and Carvedilol | Carvedilol | Significance |

|---|

| Age (years) | 63.2 ± 12.3 | 62.1 ± 11.4 | NS |

|---|

| Male (%) | 64% | 69% | NS |

|---|

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.9 ± 3.8 | 27.6 ± 4.0 | NS |

|---|

| RHR(beats/minute) | 82.7 ± 11.3 | 83.1 ± 10.6 | NS |

|---|

| NYHAclassification II (%) | 39 | 42 | NS |

|---|

| NYHAclassification III (%) | 61 | 58 | NS |

|---|

| LVEF (%) | 37.4 ± 6.3 | 36.9 ± 6.1 | NS |

|---|

| Diabetes (%) | 21 | 28 | NS |

|---|

| ArterialHypertension (%) | 46 | 67 | P < 0.05 |

|---|

b.i.d. = twice a day; CSS KCCQ = Clinical summary score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; kg/m2 = kilogram per [(metre of height) * (metre of height)]; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MI = myocardial infarction; NYHA = New York Heart Association; NS = not significant (P > 0.05; OSS KCCQ = Overall summary score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; RHR = resting heart rate’ SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 3Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Studies, (randomized experimental studies) using JBI13

View in own window

| Question | Sallam, 201615 |

|---|

| 1. Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | Unclear |

| 2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | Unclear |

| 3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | No |

| 4. Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | Unclear |

| 5. Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | Unclear |

| 6. Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | Unclear |

| 7. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | Yes |

| 8. Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analyzed? | Unclear* |

| 9. Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? | Yes |

| 10. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | Yes |

| 11. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Yes |

| 12. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes |

| 13. Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | Yes |

- *

Unclear if all patients completed follow-up quality of life measures, and NYHA class assessment.

Table 4Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Studies, (non-randomized experimental studies) using JBI13

View in own window

| Question | Bagriy 201516 |

|---|

| 1. Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | Yes |

| 2. Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | Yes |

| 3. Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | Unclear |

| 4. Was there a control group? | Yes |

| 5. Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | No |

| 6. Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analyzed? | Yes |

| 7. Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | Yes |

| 8. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Unclear |

| 9. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes |

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 5Summary of Findings of Included Primary Clinical Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Sallam, 201615 |

|---|

12-week outcome Data presented as percentage or mean ± standard deviation. | “This study demonstrated that adding ivabradine to the guideline-recommended treatment for I-CHF [ischemic chronic heart failure] in patients with a sinus rhythm and a resting HR [heart rate] exceeding 70 bpm [beats per minute] resulted in a significantly greater improvement in HRQoL [health-related quality of life] than the therapy with beta-blocker alone.” (p485) |

| Outcome | Ivabradine and Carvedilol | Carvedilol | Statistical significance |

|---|

| LVEF% | 42±17 | 37±13 | NS |

| NYHA classification (mean) | 1.5±1.3 | 1.9±0.6 | P = 0.047 |

| CSS KCCQ (score) | 82±14 | 71±21 | P = 0.002 |

| OSS KCCQ (score) | 80±14 | 68±20 | P = 0.001 |

| RHR (beats per minute) | 69±11 | 78±17 | P = 0.002 |

| Mean heart rate (beats per minute) | 71±8 | 79±10 | P < 0.001 |

| Adverse Events (number) | 16 (asymptomatic and symptomatic bradycardia, hypotension, palpitations and phosphenes) | 5 (asymptomatic bradycardia, hypotension, and palpitations) | NS for individual AEs, not reported for overall number of AEs |

| … |

| Bagriy 201516 |

|---|

5 month outcome Data presented as percentage or mean ± standard deviation. | “The results indicate that adding ivabradine to carvedilol in patients with chronic heart failure results in lower heart rates and better exercise capacity, and patients treated with ivabradine achieved higher dosages of (beta)-blocker more rapidly than patients without ivabradine.” (p17) |

| Outcome | Ivabradine and Carvedilol | Carvedilol | Statistical significance |

|---|

| LVEF% | 41.3 ± 6.9 | 38.7 ± 6.8 | NS (Note: Change from baseline in LVEF is significantly greater in ivabradine and carvedilol group, P < 0.001) |

| NYHA classification (% of patients who improved at least one step in classification) | 58% | 36% | P < 0.05 |

| RHR (beats per minute) | 61.6 ± 3.1 | 70.2 ± 4.4 | P < 0.001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 123.5 ± 5.7 | 116.4 ± 7.8 | P < 0.001 |

| 6MWT (metres) | 574.4 ± 102.3 | 527.2 ± 90.6 | P < 0.001 |

| Adverse Events (number) | 5 cases (bradycardia or visual disturbances) | 8 cases (weakness or transient bronchial obstructions) | NR |

6MWT = Six minute walk test; CSS KCCQ= Clinical summary score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NR = not reported; NS = not significant; NYHA = New York Heart Association; OSS KCCQ = Overall summary score of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; RHR = resting heart rate.

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Note: The guidelines were judged to be not eligible for this review. The systematic reviews and primary studies listed below did not have a suitable population for this review. The mean ejection fraction was less than 35%, which indicated that a high proportion of the patients would have an ejection fraction of less than 35% which is out of the scope of this review.

Guidelines

Ezekowitz

JA, O’Meara

E, McDonald, MA, et al. 2017

Comprehensive update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of heart failure.

Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1342–1433.

PubMed: PM29111106 [

PubMed: 29111106]

Systematic Reviews

Hartmann

C, Bosch

NL, de Aragao Miguita

L, Tierie

E, Zytinski

L, Baena

CP. The effect of ivabradine therapy on heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(6):1443–1453.

PubMed: PM30173307 [

PubMed: 30173307]

Primary Studies

Mert

KU, Dural

M, Mert

GO, Iskenderov

K, Ozen

A. Effects of heart rate reduction with ivabradine on the international index of erectile function (IIEF-5) in patients with heart failure.

Aging Male. 2018;21(2):93–98.

PubMed: PM28844168 [

PubMed: 28844168]

Sisakian

H, Sargsyan

T, Khachatryan

A. Effect of selective heart rate reduction through sinus node If current inhibition on severely impaired left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure.

Acta Cardiol. 2016;71(3):317–22.

PubMed: PM27594127 [

PubMed: 27594127]

Abdel-Salam

Z, Rayan

M, Saleh

A, Abdel-Barr

MG, Hussain

M, Nammas

W. I(f) current inhibitor ivabradine in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: impact on the exercise tolerance and quality of life.

Cardiol J. 2015;22(2):227–232.

PubMed: PM25179314 [

PubMed: 25179314]

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Ivabradine for adults with stable chronic heart failure: a review of clinical effectiveness. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 May. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.