Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- CI

confidence interval

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HD

high dose

- ICER

incremental cost effectiveness ratio

- IIV3

trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

- IIV4

quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

- ID

intra-dermal

- IM

intramuscular

- MA

meta-analysis

- OR

odds ratio

- QALY

quality adjusted life years

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SD

standard dose

- SOTR

solid organ transplant

Context and Policy Issues

Influenza is a respiratory illness caused by a viral infection, with an peak season usually lasting from mid-to-late-autumn to late-winter.1 Currently, the annual influenza vaccine is recommended for all individuals over the age of 6 months and without contraindications, and especially recommended for individuals at high-risk of contracting influenza, high-risk of complications from influenza, or for individuals in proximity to others who may be at high-risk of complications.1 High risk individuals include the elderly (≥65 years), young children (6 months to 59 months of age), residents of nursing homes, pregnant women, individuals with chronic health conditions (including immunocompromised individuals), and Indigenous peoples.1

Contraindications to receipt of the influenza vaccine include previous anaphylaxis to influenza vaccines, serious acute illness (in this case, the vaccine should be postponed until the illness has passed), development of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) within 6 weeks post-administration of a previous vaccine, and being under 6 months of age.1

There are multiple preparations of influenza vaccines available in Canada. This includes inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV, including trivalent and quadrivalent formulations), high-dose IIV, adjuvanted IIV, and live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV).1 As of the writing of this report, there was only one high-dose formulation approved in Canada, the intra-muscular Fluzone® High-Dose influenza vaccine, a trivalent formulation with 60µg of hemagglutinin (HA) in a 0.5mL dose;1 this is compared to the standard dose of vaccine, which is ordinarily 15µg HA in 0.5mL. High-dose vaccine is indicated for use in adults aged 65 and older.2

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the comparative clinical evidence of high-dose influenza vaccination compared with standard-dose (and double-dose) influenza vaccine or placebo. Additionally, the comparative cost effectiveness and evidence-based guidelines were analyzed to facilitate and support decision making with regards to high-dose influenza vaccine.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness of high dose influenza vaccine in older adults or adults who are immunocompromised?

What is the cost-effectiveness of high dose influenza vaccine in older adults or adults who are immunocompromised?

What are the evidence-based guidelines associated with the use of high dose influenza vaccine in older adults or adults who are immunocompromised?

Key Findings

Three systematic reviews, four randomized controlled trials (RCTs), four economic evaluations, and one guideline were identified regarding high-dose influenza vaccination.

For immunocompromised individuals, high-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (HD-IIV3) appeared to have no statistically significant difference in safety when compared to standard dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (SD-IIV3). This evidence was very limited, with methodological concerns and different and heterogeneous populations for each study.

For elderly adults 65 years of age or older, HD-IIV3 appeared to have similar or higher effectiveness at reducing influenza illnesses, hospitalization, and mortality, when compared to SD-IIV3, with no statistical differences in adverse events. HD-IIV3 also appeared to be cost effective from both a Canadian and US perspective, when compared to SD-IIV3, no vaccination, and standard dose quadrivalent IIV.

One high-quality evidence based guideline was identified in the literature, recommending HD-IIV3 for elderly adults 65 or older over standard dose vaccines on an individual level. On a programmatic level, all vaccine strategies, including high dose, were recommended. There were no evidence based guidelines or cost-effectiveness studies focusing on immunocompromised populations.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, the Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, economic studies and guidelines. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2013 and November 29, 2018.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2013. Guidelines with unclear methodology were also excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included systematic reviews were critically appraised by one reviewer using AMSTAR 2,3 randomized studies were critically appraised using the Down’s and Black Checklist,4 economic studies were assessed using the Drummond checklist,5 and guidelines were assessed with the AGREE II instrument.6 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

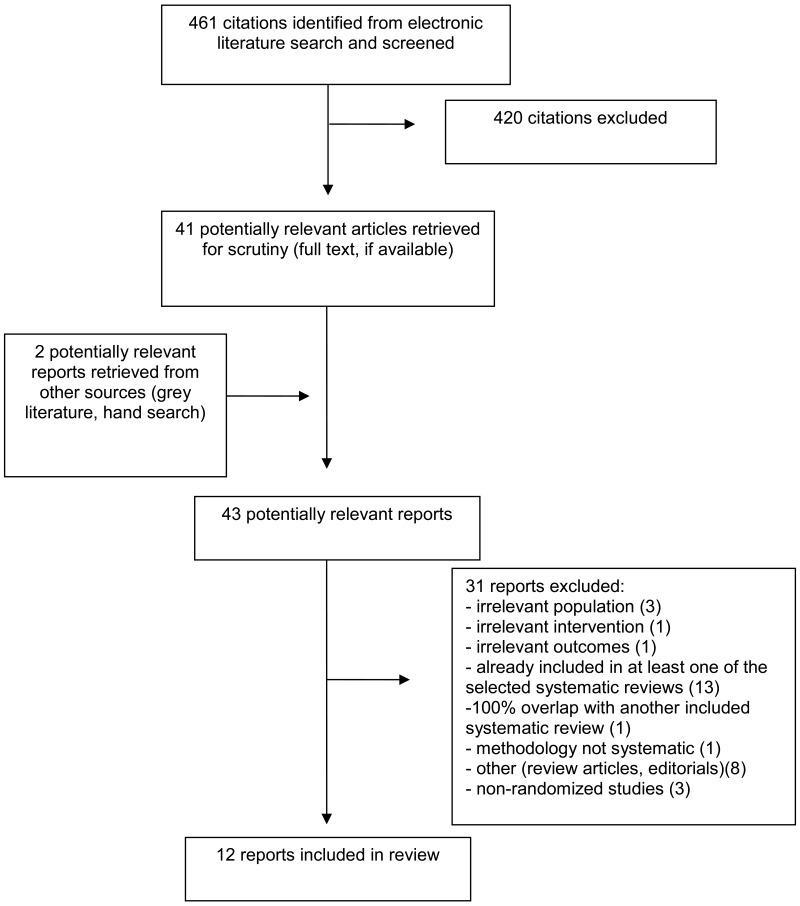

A total of 461 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 420 citations were excluded and 41 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Two potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 31 publications were excluded for various reasons, and 12 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised three systematic reviews (SRs),7–9 four RCTs,10–13 four economic evaluations,14–17 and one evidence-based guideline,1 with an accompanying systematic review and update.18,19

Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA20 flowchart of the study selection. One additional systematic review21 was identified that also fit the inclusion criteria (one relevant primary study). However, this review was excluded as the relevant primary study was already included in another, more comprehensive systematic review, resulting in 100% overlap of primary studies.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Systematic Reviews

Three SRs were identified.7–9 Two SRs were published in 20187,8 and one was published in 2017.9 One study exclusively included RCTs,9 whilst the remaining two included both non-randomized studies (NRS) and RCTs.7,8 One SR searched up to March 2018,8 one SR searched until June 2017,7 and one SR9 searched from inception until ‘present’ (definition of ‘present’ was not clarified). However, the detailed search strategy within the appendix specified that EMBASE was searched until February 2016, so the search date was likely around this time. Searches were likely not performed after May 2017 (publication of the SR), but search dates for the other databases in this SR were unclear.9

Two SRs included meta-analyses (MAs).8,9

Overlap of the included primary studies across the included SRs (in addition to the SR accompanying the guideline) is provided in Appendix 5.

Randomized Controlled Trials

All of the included trials were randomized controlled trials.10–13 Two RCTs were double-blinded,10,11 one RCT was a pilot double-blinded randomized trial,12 and one RCT was a parallel, single centre RCT.13

Economic Evaluations

Two economic evaluations15,16 were based on data from an RCT (study ID: FIM12).22 The remaining economic evaluations were model based,17,23 with one economic evaluation employing a Markov model.23

The perspective for the economic evaluations were societal15–17,23 and public payer based.16 The public payer perspective included the Medicare perspective for the US based analysis.16

The majority of evaluations assumed no herd immunity,17,23 that lost productivity was equivalent to the average daily wage of participants, and that days lost were equivalent to the number of sought medical visits.15,16

Guidelines

One guideline with an accompanying SR was identified.1,18,19 The guideline development group was the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), with a specific working group for influenza vaccination. Quality of recommendations and evidence were reported, but the methodology for assessing quality was not clear. Recommendations were created from the NACI and the influenza working group, but the methodology for consensus was unclear.

Two grades were assigned to the recommendations – Grade A and Grade I. Grade A was defined as “NACI concludes that there is good evidence to recommend immunization”, and Grade I was defined as “NACI concludes that there is insufficient evidence (in either quantity and/or quality) to make a recommendation, however other factors may influence decision-making.”24

Country of Origin

Two included SRs were from Canada,8,9 and one SR was from the USA.7 All included RCTs were from the USA,11–13 with the exception of one Canadian based RCT.10 One economic evaluation was Canadian, and based off a Canadian perspective.15 The remaining three economic evaluations were based on a USA perspective.16,17,23 The included guideline was Canadian, and the included recommendations were intended for a Canadian audience.18,19

Patient Population

One SR focused on adult and pediatric patients receiving solid organ transplants (SOTRs),7 and two SRs focused on adults 65 years of age and older.8,9 Only the relevant data on high dose vaccine in adults (18 and older) were retrieved from Chong et al. 2018.7

All included RCTs were on immunocompromised individuals.10–13 These included SOTRs,10 hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients,11 cancer patients,12 and patients with HIV on stable antiretroviral therapy.13

All economic evaluations were based on vaccine use in adults 65 years of age and older.15–17,23 One economic evaluation was specific to Canadian adults 65 and older,15 and the remaining three were specific to US adults 65 and older.16,17,23

The included guideline was intended for health care providers and public health practitioners, policy makers, and program planners, and the recommendations relevant for this report were intended for adults 65 and older.1

Interventions and Comparators

All included studies examined high-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (HD-IIV3) in comparison to standard dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (SD-IIV3).1,7–13,15–18,23 All studies examined 60µg of hemagglutinin (HA) in a 0.5mL dose, with the exception of one SR, which had one relevant study examining an “HD intra-dermal” vaccine of two doses of 9µg HA in 0.1mL.7

Other comparisons in addition to SD-IIV3 were HD-IIV3 compared to “alternative influenza vaccination strategies” (including use of intramuscular [IM] or intra-dermal [ID] HD, SD administered more than once per season, and use of adjuvanted vaccine),7 SD quadrivalent IIV,17,23 and no vaccination,17,23

Outcomes

The relevant outcomes included in the SRs were safety and adverse events (AEs),7,9 efficacy,8 influenza related clinical outcomes and infection,7,9 and mortality.8,9

The relevant outcomes in the included RCTs were safety and AEs,10–13 influenza infection,10 hospitalization,10 and reactogenicity.11

The included economic evaluations had outcomes of quality adjusted life years (QALYs)15,17,23 and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs),15–17 threshold analyses15 and cost effectiveness acceptability.23

The outcomes included in the SR that informed the guideline included laboratory confirmed influenza, hospitalizations, vaccine effectiveness, and safety.1

Cost Considerations

For the four economic evaluations,15–17,23 a variety of costs were considered.

The US-based16 and Canadian-based15 economic evaluations with similar methodologies included the costs of vaccine (in US$ or CAN$ respectively), prescription drugs, medical visits, and hospital admissions. For the third party payer perspectives, the costs of non-prescription drugs and lost workforce productivity were added.

In the Markov-model based analysis,23 the cost of the vaccine, costs of influenza illness, costs of office visits, cost of prescription medication, non-medical direct costs, and costs of hospitalization were considered.

In the last economic evaluation,17 costs of vaccine, primary care medically attended influenza, and influenza-related hospitalizations were considered. Medication costs were considered from a societal perspective.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in Appendix 3

Systematic Reviews

The included systematic reviews had clearly outlined inclusion criteria, and detailed information about included studies. Quality or risk of bias were assessed by two SRs,8,9 but was not assessed by one SR.7

One SR did not detail the full methodology of the search performed, and only searched two databases (with no grey literature).7 One SR searched grey literature, hand searched reference lists, searched trial registries, and had an a priori protocol.9 The third SR searched multiple databases and included a detailed search strategy, but did not search grey literature, trial registries, reference lists, or consult experts in the field.8

The funding sources of each primary study were not detailed in two SRs.7,8 One SR extracted the funding information, and examined industry-sponsored trials versus other sponsored trials for the outcome of immunogenicity, but did not report funding information for included individual trials.9

The two SRs with included MAs8,9 likely had appropriate methods and justification for combining their trials into meta-analyses. Additionally, both SRs performed sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the results.8,9 Although one SR8 combined RCTs and NRS in its MA, sensitivity analyses were performed with only RCTs, with no difference in results. The remaining three outcomes pooled for the MA were of similar study design (retrospective cohort study).8

Randomized Controlled Trials

The randomized controlled trials were of low to moderate quality. All included trials had a clear hypothesis, detailed outcomes, detailed adverse events, actual probability values, patients in both intervention and comparator groups were from the same populations, and compliance with the treatment was likely.10–13

Power calculations were considered in two RCTs,10,13 but the power calculations were performed for immunogenicity outcomes only.10,13 This means that the studies may have been powered for immunogenicity outcomes, but not sufficiently powered to detect a clinically or statistically meaningful difference for adverse events or safety.

All included studies were randomized, and details of the randomization sequence were included in two studies10,13 but the methodology for the randomization sequence was not clear in the other two RCTs.11,12 Methodology for the statistical testing of safety outcomes was unclear in two studies,10,12 and statistical testing was not performed at all in another RCT.13 P values were not fully reported in two studies, and both of these studies were manufacturer supported and funded.11,12

Economic Evaluations

One economic evaluation was specific to the Canadian context;15 the other three economic evaluations were specific to the US context, and may not apply to Canada.16,17,23

In the included Canadian study,15 the price of the HD-IIV3 was estimated from the American pricing and not from official Canadian pricing, as HD-IIV3 was not on the Canadian market at the time of the study, which may not be reflective of actual pricing. Additionally, only 5% of the patients within the reference RCT were Canadian, and although the patients were found to be homogenous enough to be used as a pooled sample, this may not completely reflect the Canadian experience with influenza, hospitalization, and illness in general.15 Additionally, this study (along with two others16,17) were manufacturer supported, with the authors being employed by the manufacturer of HD vaccinations. One economic evaluation was not supported by the manufacturer, although some authors had received grant funding or had conflicts of interest related to the manufacturer of high-dose vaccinations.23

The included Canadian study and one US-based study had almost identical methodology for their economic evaluations, and made many assumptions to simplify the modeling, such as no herd immunity (i.e., no indirect protection, although this assumption may be appropriate as seniors are not considered primary drivers of influenza transmission), that wages lost due to influenza were equivalent to the average daily wage (of Canadian citizens and US citizens respectively), and that the number of physician visits were equivalent to the number of days of productivity lost.15,16 These assumptions, whilst simplifying the model, may not be truly accurate in reality, as some individuals may take more days to recover from influenza than the number of physician visits, and it does not take into account that individuals of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to contract influenza and be affected negatively by the infection.25 In addition, some conclusions are reported differently from one another, with some results not reported in their entirety (e.g., for 1000 bootstrapped samples, the percentage of samples that are both cost-saving and more effective [lower right quadrant in the scatter plot] is reported for the subgroup analysis [cardiorespiratory subgroup – in which it looks favourable], but not the overall analysis [in which it looks comparatively less favourable]).15,16 This appeared to be selective reporting of some outcomes.

The other two economic evaluations also did not take into account herd immunity, but provided some justification for this assumption.17,23 In one economic evaluation comparing HD-IIV3 to other vaccine strategies, although the effectiveness data for HD-IIV3 was based on a large RCT, the effectiveness data for comparators were derived from NRS and the efficacy of SD-IIV4 was estimated using the comparative relative effectiveness of SD-IIV4 compared with SD-IIV3, based on an average likelihood of contracting influenza between 1999 and 2014.17 In another economic evaluation, mortality from ‘other’ causes was assumed to be unrelated to the vaccination and the pricing of HD-IIV3 was estimated from the average wholesale price, which may not be accurate.23

Despite some limitations, overall the economic evaluations were of good quality, with all sources of estimates and methods to value benefits clearly stated.15–17,23 The purpose and research questions are clear, and the time horizon, discount rates, and approach to sensitivity analyses are reported. These reported time horizons appeared to be appropriate for the study questions (one influenza season, with mortality and quality adjusted life years lost due to premature death modeled over the lifetime). Additionally, the conclusions follow clearly from the reported data.15–17,23

Guideline

The included guideline is a chapter of the broader Canadian Immunization Guide and is overall, of high quality.1 It is based on a robust and systematic literature review,18,19 with clear methods, and a connection between the evidence presented and the resulting recommendations. The recommendations are specific, the populations are well-defined, and the target audience for the guideline is clear.1

One limitation of the recommendations is that cost-effectiveness data were not within scope for the literature review, therefore, costing data was not taken into account in the development of the recommendations. Additionally, the perspective of the target populations were not sought, and information regarding implementation, barriers, and facilitators was not provided.1

Summary of Findings

Appendix 4 presents a table of the main study findings and authors’ conclusions.

Clinical Effectiveness and Safety of HD-IIV3

Adults aged 65 and older

Two systematic reviews were included regarding the clinical effectiveness and safety of HD-IIV3 vaccinations.8,9 Both SRs included meta-analyses, one including seven relevant studies (one study not included in MA due to overlap of populations),8 and the other including three relevant studies.9

For odds ratios, HD-IIV3 was significantly more effective in preventing influenza-like illness (Odds ratio [OR]: 0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71 to 0.91), influenza hospitalization (OR: 0.82, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.92), pneumonia hospitalization (OR: 0.76, 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.86), cardiorespiratory hospitalization (OR: 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.93) and all cause hospitalization (OR: 0.98, 95% CI, 0.85 to 0.98) when compared to SD-IIV3. It was not significantly more effective for post-influenza mortality or all-cause mortality.8 The P-values for pneumonia hospitalization and cardiorespiratory hospitalization were nonsignificant, but the confidence intervals were significant. This was likely an error in reporting of the P-values.8

For pooled relative efficacy, HD-IIV3 was significantly more effective than SD-IIV3 on all outcomes (P ≤ 0.009), except post-influenza mortality and all-cause mortality (P = 0.240 and P = 0.514 respectively). In sensitivity analyses using only RCTs, these results stayed consistent with the four outcomes examined (influenza like illness, pneumonia hospitalization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality). The RCTs did not address influenza hospitalization, post-influenza mortality, or cardiorespiratory hospitalization.8

The risk ratio of laboratory confirmed influenza infection for HD-IIV3 compared with SD-IIV3 was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.65 to 0.90, based on three RCTs) in one SR,9 with a 24% greater vaccine efficacy in the HD-IIV3 group. These results were consistent with the other systematic review;8 however, these reviews used overlapping studies for these outcomes, so these results are not independent from one another.

Immunocompromised individuals

One SR and four RCTs were included that examined the effectiveness and safety of HD-IIV3 in immunocompromised individuals.7,10–13

In the included SR, one RCT was relevant to the research question, and examined safety outcomes. Local adverse events were more common in ID administered HD-IIV3 (two doses of 9µg) than in intra-muscular SD-IIV3 (P < 0.001 for erythema, induration, pruritus, and tenderness).7 Systemic adverse events (fatigue, gastro-intestinal symptoms, and subjective fever) were not significantly different, with the exception of gastro-intestinal symptoms (P = 0.0016).7

The included RCTs mostly examined safety outcomes.10–13 In SOTRs, there were no significant differences in erythema, induration, tenderness, fever, gastro-intestinal events, arthralgia, or fatigue.10 At 6 months, there was also no difference in hospitalization, influenza, or rejection episodes.10 In hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, there were no differences between groups except in combined solicited injection site reactions.11 In cancer patients, there were no serious adverse events or differences in adverse events, and although solicited adverse events were “more common” in HD-IIV3 recipients, there were no P values reported.12 In patients with HIV, overall local adverse events appeared to be numerically higher in the HD-IIV3 group compared with the SD-IIV3 (30 vs. 16), and systemic adverse events appeared to be numerically similar, but no adverse event outcomes were tested statistically.13

Cost Effectiveness of HD-IIV3

Adults aged 65 and Older

Four economic evaluations were included.15–17,23 In a Canadian analysis, HD-IIV3 was cost saving to the public payer up to a threshold of CAN$79 per injection.15 HD-IIV3 dominated from both societal and public payer perspective over SD-IIV3 (i.e., was more effective and more cost-saving).15 Although the cost of HD-IIV3 (vaccine only) was CAN$60 higher than SD-IIV3, and additional expenses of $25.97 per patient, it yielded an additional 181% financial return.15

In a US based analysis, HD-IIV3 was cost saving from a societal perspective, with total costs (including cost of vaccine, prescription and non-prescription drugs, emergency room visits, urgent-care visits, hospital admissions, productivity losses and total health care payer costs) being US$128 higher with the use of SD-IIV3.16 Although HD-IIV3 was US$19.75 (vaccine only) more expensive per patient, it generated 587% financial return (US$116 per participant).16 HD-IIV3 dominated from both a societal and public payer perspective.

In another US-based analysis,23 the incremental cost of HD-IIV3 (base case) compared with IIV4 was US$6.46 (vaccine and illness only, with an effectiveness of −0.0051 QALYs). This resulted in an incremental effectiveness of 0.00021 QALYs gained, and an ICER of US$31,214 per QALY. In sensitivity analyses (probabilistic sensitivity analysis – 5000 iterations), if willingness-to-pay was US$100,000 per QALY, HD-IIV3 was favoured in 68.5% of cases, and if willingness-to-pay was US$50,000 per QALY, HD-IIV3 is favoured in 49.3%. At a willingness-to-pay of ≥US$25,000, HD-IIV3 is the strategy most likely to be favoured compared with SD-IIV3, SD-IIV4, and no vaccine.23 Favourability was most sensitive to variations in SD-IIV3 effectiveness – if the effectiveness of SD-IIV3 was greater than 15.5%, HD-IIV3 was favoured. If the effectiveness was below 15.5%, HD-IIV3 was not favoured over other strategies.

In a third US-based analysis,16 the probability that HD-IIV3 dominates SD-IIV3 was 60% to 71% for QALY valuations (willingness-to-pay) of US$50,000 to US$100,000 per QALY. For these same QALY valuations, the probability that HD-IIV3 dominates SD-IIV4 was 70% to 81%. Compared with SD-IIV4, HD-IIV3 dominated from a societal perspective.16 From a third party payer perspective, the ICER was US$4365 per QALY. Compared with SD-IIV3, the ICER for HD-IIV3 from a societal and third payer perspective was US$5299 per QALY and US$10,530, respectively.16 The probability that HD-IIV3 dominates SD-IIV4 and SD-IIV3 is 39% and 29% respectively.16

Immunocompromised Individuals

There were no cost-effectiveness studies regarding immunocompromised individuals identified.

Evidence-Based Guidelines for HD-IIV3

Adults aged 65 and Older

One evidence based guideline from the NACI was included.1 The NACI recommended that any of the four available vaccines should be used in adults 65 and older, but there was insufficient evidence to make a comparative recommendation regarding these vaccines from a programmatic level. At an individual level, NACI recommended HD-IIV3 be offered over SD-IIV3 to individuals 65 and older. However, there was insufficient evidence to make any recommendation for HD-IIV3 compared with MF-59-adjuvanted IIV3 or IIV4.1 The evidence from the SR18,19 informing these guidelines also overlapped substantially with the included SRs on elderly adults.8,9

Immunocompromised Individuals

No evidence-based guidelines regarding immunocompromised individuals were identified.

Limitations

One limitation of the current report is the lack of guidelines and cost-effectiveness studies focusing on immunocompromised individuals. Additionally, there was only one SR with one relevant primary study that was identified regarding this population. The included primary studies, although focusing on immunocompromised individuals, had patients with different disorders and conditions. Therefore, there was limited evidence overall on immunocompromised patients receiving high dose influenza vaccinations.

There was only one cost-effectiveness study from a Canadian perspective identified in the literature. This study looked at HD-IIV3 vaccination strategies compared with SD-IIV3 vaccination strategies, but did not compare HD-IIV3 with other available influenza vaccinations, such as no vaccination, quadrivalent vaccines, or live attenuated vaccines. Therefore, these comparisons are missing from a Canadian costing perspective, making conclusions about the overall cost-effectiveness of HD-IIV3 within a vaccination program difficult.

Similarly, all included systematic reviews (with the exception of one) and RCTs examined intra-muscular HD-IIV3 in comparison to SD-IIV3. HD-IIV3 is currently the only high dose vaccination formulation approved for use in Canada, and there is a lack of comparative studies examining HD vaccines compared to other available vaccination strategies apart from SD-IIV3. This evidence gap limits some conclusions that can be made about the role of HD-IIV3 vaccinations in overall vaccination treatment programming.

Finally, the majority of the studies comparing HD-IIV3 vaccinations to SD-IIV3 vaccinations in elderly adults were manufacturer sponsored, were conducted by authors employed by the manufacturer, or had authors associated with the manufacturer, and therefore had a conflict of interest. Although these associations and sponsorships were transparent, it is unknown how this may have influenced the findings.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Three systematic reviews, four RCTs, four economic evaluations, and one guideline were identified regarding high-dose influenza vaccination.

Evidence from four low to moderate quality RCTs and one SR showed no difference in safety outcomes for immunocompromised individuals (including those with solid organ transplants, cancer, stem cell transplants, and HIV). There were many methodological concerns with these studies, including no assessment of quality or risk of bias, low sample sizes and unclear power, missing details of randomization sequence, and lack of statistical testing. Many of these studies may not have been sufficiently powered to detect a statistically meaningful difference in safety outcomes, and therefore may not be reliable.

Evidence from two SRs showed that in people 65 years of age and older, high dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine showed no difference or was more effective in preventing influenza illnesses, influenza hospitalization, pneumonia hospitalization, and mortality. However, these SRs shared many studies and overlapped, so these results should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, there were some concerns with reporting of incorrect P values, unknown search methodology, and unknown primary study funding sources.

In four economic evaluations, HD-IIV3 was compared to SD-IIV3 for elderly people aged 65 and older. HD-IIV3 seemed to be a cost-effective option from both a societal and public payer perspective in both a Canadian and US based economic evaluation. In a separate analysis, HD-IIV3 was most likely to be favoured at a willingness to pay of US$25,000 or more. The probability that HD-IIV3 dominates SD-IIV3 and SD-IIV4 from a US perspective was 39% and 29%, respectively. All of the included economic evaluations were supported by, or had authors with conflicts of interest related to the manufacturer of high-dose vaccine.

Finally, one high quality evidence-based guideline was identified. The NACI recommends on an individual level that high-dose trivalent IIV be offered over standard dose vaccine for individuals aged 65 or older. At a programmatic level, the NACI recommends all four available options be offered to this population group. There were no recommendations for immunocompromised individuals specifically regarding high dose vaccinations.

Due to a lack of trials comparing HD-IIV3 to other available vaccination strategies, more research addressing this comparison may help reduce uncertainty with regards to recommendations on a programmatic level. Additionally, more trials on immunocompromised adults with larger sample sizes will help to reduce the evidence gap regarding HD-IIV3 for this population.

References

- 1.

- 2.

Sanofi Pasteur. Fluzone® high-dose influenza virus vaccine trivalent types A and B (split virion). 2017.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

Chong

PP, Handler

L, Weber

DJ. A systematic review of safety and immunogenicity of influenza vaccination strategies in solid organ transplant recipients.

Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(11):1802–1811. [

PubMed: 29253095]

- 8.

Lee

JKH, Lam

GKL, Shin

T, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(5):435–443. [

PubMed: 29715054]

- 9.

Wilkinson

K, Wei

Y, Szwajcer

A, et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose influenza vaccine in elderly adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Vaccine. 2017;35(21):2775–2780. [

PubMed: 28431815]

- 10.

Natori

Y, Shiotsuka

M, Slomovic

J, et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of high-dose vs standard-dose influenza vaccine in adult solid-organ transplant recipients.

Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(11):1698–1704. [

PubMed: 29253089]

- 11.

Halasa

NB, Savani

BN, Asokan

I, et al. Randomized double-blind study of the safety and immunogenicity of standard-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine versus high-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients.

Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(3):528–535. [

PubMed: 26705931]

- 12.

Jamshed

S, Walsh

EE, Dimitroff

LJ, Santelli

JS, Falsey

AR. Improved immunogenicity of high-dose influenza vaccine compared to standard-dose influenza vaccine in adult oncology patients younger than 65 years receiving chemotherapy: A pilot randomized clinical trial.

Vaccine. 2016;34(5):630–635. [

PubMed: 26721330]

- 13.

McKittrick

N, Frank

I, Jacobson

JM, et al. Improved immunogenicity with high-dose seasonal influenza vaccine in HIV-infected persons: a single-center, parallel, randomized trial.

Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):19–26. [

PubMed: 23277897]

- 14.

Raviotta

JM, Smith

KJ, DePasse

J, et al. Cost-effectiveness and public health impact of alternative influenza vaccination strategies in high-risk adults.

Vaccine. 2017;35(42):5708–5713. [

PMC free article: PMC5624037] [

PubMed: 28890196]

- 15.

Becker

DL, Chit

A, DiazGranados

CA, Maschio

M, Yau

E, Drummond

M. High-dose inactivated influenza vaccine is associated with cost savings and better outcomes compared to standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccine in Canadian seniors.

Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(12):3036–3042. [

PMC free article: PMC5215371] [

PubMed: 27669017]

- 16.

Chit

A, Becker

DL, DiazGranados

CA, Maschio

M, Yau

E, Drummond

M. Cost-effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccine in adults aged 65 years and older: an economic evaluation of data from a randomised controlled trial.

Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(12):1459–1466. [

PubMed: 26362172]

- 17.

Chit

A, Roiz

J, Briquet

B, Greenberg

DP. Expected cost effectiveness of high-dose trivalent influenza vaccine in US seniors.

Vaccine. 2015;33(5):734–741. [

PubMed: 25444791]

- 18.

- 19.

- 20.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 21.

Wang

KN, Bell

JS, Chen

EYH, Gilmartin-Thomas

JFM, Ilomaki

J. Medications and Prescribing Patterns as Factors Associated with Hospitalizations from Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review.

Drugs Aging. 2018;35(5):423–457. [

PubMed: 29582403]

- 22.

DiazGranados

CA, Dunning

AJ, Kimmel

M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults.

N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):635–645. [

PubMed: 25119609]

- 23.

Raviotta

JM, Smith

KJ, DePasse

J, et al. Cost-Effectiveness and Public Health Effect of Influenza Vaccine Strategies for U.S. Elderly Adults.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):2126–2131. [

PMC free article: PMC5302117] [

PubMed: 27709600]

- 24.

- 25.

- 26.

Shay

DK, Chillarige

Y, Kelman

J, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of High-Dose Versus Standard-Dose Influenza Vaccines Among US Medicare Beneficiaries in Preventing Postinfluenza Deaths During 2012-2013 and 2013-2014.

J Infect Dis. 2017;215(4):510–517. [

PubMed: 28329311]

- 27.

Izurieta

HS, Thadani

N, Shay

DK, et al. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines in US residents aged 65 years and older from 2012 to 2013 using Medicare data: a retrospective cohort analysis.

Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(3):293–300. [

PMC free article: PMC4834448] [

PubMed: 25672568]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country, Funding Source | Study Designs and Numbers of Primary Studies Included | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

Chong, 20187 USA Funding Source NR | 6 RCTs 1 prospective cohort study | Patients (adult and pediatric) SOTRs receiving heart, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, intestinal, or multivisceral transplants, alone or in combination 943 patients total Transplant types Kidney: n= 422 Liver: n = 229 Lung: n = 181 Heart: n = 89 Intestinal: n = 1 Multi-organ: n = 21 | Intervention: “Alternative influenza vaccination strategies” including

- -

HD IIV3 (1 study) - -

MF59-adjuvanted vaccine (1 study) - -

ID IIV3 (1 study) - -

2 sequential doses of SD IIV3 were administered 5 or 4–6 weeks apart (2 studies) - -

9μg of antigen per strain administered simultaneously in 2 doses (1 study) - -

15μg of antigen per strain in a single dose (1 study)

Comparator:SD IIV3 (15μg of antigen of each of H1N1 and H3N2 strains and 1B strain in a single 0.5-mL IM dose | Vaccination immunogenicity Safety 6 months |

Lee, 20188 Canada Sanofi Pasteur | 5 RCTs (2 cluster randomized; 3 individually randomized) 4 retrospective cohort | Adults over 65 years of age | Intramuscular dose of HD-IIV3 Intramuscular dose of SD-IIV3 | Efficacy, effectiveness Influenza related clinical outcomes All-cause hospitalization Mortality |

Wilkinson, 20179 Canada No specific funding grant received | 7 RCTs | Adults over 65 years of age | HD influenza vaccine SD influenza vaccine | Laboratory-confirmed influenza infection Immunogenicity and seroprotection Influenza –associated death and AEs |

AE = adverse events; IIV3 = trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; IIV4 = quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; HD = high dose; ID = intradermal; IM = intra-muscular; NR = not reported; SD = standard dose; SOTR = solid organ transplant recipient; RCT = randomized controlled trial

Table 3Characteristics of Included Randomized Controlled Trials

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country, Funding Source | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) Statistical Analysis | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

Natori, 201810 Canada Partially funded by the Multi-Organ Transplant Program | Adult patients (≥18 years) who received an organ transplant (kidney, liver, heart, lung and pancreas, or combined organs) with a functioning allograft over 3 months prior, had not received an influenza vaccine for the 2016–2017 season, had no egg allergies, had not experienced febrile illness within one week prior, did not have active cytomegalovirus infection, a previous life-threatening reaction to influenza vaccine, had received intravenous immunoglobulin in the past 30 days or was planning to receive intravenous immunoglobulin in the next 4 weeks Median time since transplant 38 months Mean (range) age 57 (18 to 86) None of the patient characteristics statistically differed between groups | HD-IIV3 vaccine (n = 87) 0.5mL volume, 60 µg of each 3 strains SD-IIV3 (n = 85) 0.5mL volume, 15 µg of each 3 strains Primary outcome per-protocol analysis, secondary outcomes intent-to-treat analysis Statistical tests used not clear | Primary Outcomes: Vaccine immunogenicity by HAI 4 weeks later - seroconversion to at least 1 of the 3 vaccine antigens. Secondary Outcomes: Local and systemic AEs

- -

Mild (no interference in daily activities) - -

moderate (some interference in daily activities) - -

Severe (participants unable to perform daily activities)

Influenza infection Hospitalization Biopsy-proven acute rejection episodesFollow-up for AEs and secondary outcomes of 2 days, 7 days, 6 months |

Halasa, 201611 USA Sanofi Pasteur | Adult allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients Median time after transplantation: 7.9 mo Range: 5.7 to 105.6 months Mean age: 50.1 years Range: 19.6 to 72.8 years 61,4% Male 100% White Two group comparable except in baseline total IgC levels, higher in HD-IIV3 group, P = 0.025 | HD-IIV3 vaccine (n = 29) 0.5mL volume, 60 µg of each 3 strains SD-IIV3 (n = 15) 0.5mL volume, 15 µg of each 3 strains Wilcoxon rank sum test or Pearson chi-square test | Reactogenicity and safety

- -

Frequency of solicited injection-site and systemic reactogenicity within the first 7 days after each vaccination event - -

Unsolicited AEs within 28 days after vaccination - -

SAEs up to 180 days after final vaccination

Immunogenicity180 days |

Jamshed, 201612 USA Supported by Sanofi Pasteur, funding in part by the Rochester General Hospital KIDD Grant | Adult (18 to 65 years) with a life expectancy > 3 months receiving chemotherapy for malignancy who had not received the influenza vaccine yet Mean age: HD-IIV3: 53.9 years SD-IIV3: 52.9 years P = NS for age, sex, type of cancer, chemotherapy intent, number of prior regimes | HD-IIV3 vaccine (n = 54) 0.5mL volume, 60 µg of each 3 strains SD-IIV3 (n = 51) 0.5mL volume, 15 µg of each 3 strains Statistical analysis on safety outcomes NR | Immunogenicity AEs and SAEs 4 weeks ± 7 days |

McKittrick, 201313 USA National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Center for AIDS Research of the University of Pennsylvania | Adults >18 years with HIV receiving stable antiretroviral therapy Median age (range): HD-IIV3: 44 (35 to 50) SD-IIV3: 46 (37 to 53) HD-IIV3 64% Male SD-IIV3 77% Male HD-IIV3 61% African American SD-IIV3 78% African American No statistical testing for baseline characteristics | HD-IIV3 vaccine (n = 100) 0.5mL volume, 60 µg of each 3 strains SD-IIV3 (n = 95) 0.5mL volume, 15 µg of each 3 strains | Immunogenicity Safety Up to 28 days |

AE = adverse events; HAI = hemagglutination inhibition assay; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; mL = millilitres; mo = month; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SAE = serious adverse events; SD = standard deviation; ST = solid tumour

Table 4Characteristics of Included Economic Evaluations

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country, Funding Source | Type of Analysis, Time Horizon, Perspective | Decision Problem | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Approach | Clinical and Cost Data Used in Analysis | Main Assumptions |

|---|

Becker, 2016 Canada Sanofi Pasteur | Cost-utility analysis One influenza season, QALYs lost due to death during the study were captured over a lifetime Canadian perspective: public payer and societal perspectives | Determine if vaccination with HD-IIV3 will have economic benefit in the Canadian context | Population based on population from FIM12,22 ~32,000 seniors (≥65 years) | HD-IIV3 SD-IIV3 | Trial-based (based on FIM1222) | Clinical data Use of drugs, emergency and urgent care room visits, hospital admissions within 30 days of illness Cost Data Cost of HD-IIV and SD-IIV Cost of non-prescription and prescription medications Cost of hospitalizations Cost of lost productivity | Assumed the list price of HD-IIV3 would be the same as in the US as the dollars were approximately at par in 2013/2014 Assumed all non-prescription medication followed pricing of one Shoppers Drug Mart in 2014, and all prescription medications had a 8% upcharge and $8.83 dispensing fee All lost productivity was estimated from average daily wage for Canadians, assumed the number of medical visits was equivalent to number of days of productivity lost |

Raviotta, 201623 USA National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number R01GM11 1121 | Markov model Single influenza season Societal perspective | Cost-effectiveness analysis looking at vaccine strategies in older individuals | US adults over 65 years | HD-IIV3 SD-IIV3 SD-IIV4 No vaccine | Markov model | Clinical data Vaccine effectiveness Vaccine use Influenza cases Influenza-related deaths, Influenza-related hospitalizations Cost data Vaccine prices Hospitalization costs | Assuming that influenza vaccination affected only deaths due to influenza and not those due to other causes Assumed vaccinating elders had no herd immunity effects Assumes that all non-influenza events will occur identically between modeled strategies Assumed that risk is homogenous within the cohort. |

Chit, 2015a16 USA Sanofi Pasteur | Cost-utility analysis One influenza season, QALYs lost due to death during the study were captured over a lifetime Medicare and societal perspective | Determine if vaccination with HD-IIV3 will have economic benefit in the American context for adults 65 and older | Population based on population from FIM12,22 31,989 seniors (≥65 years) | HD-IIV3 SD-IIV3 | Trial-based (based on FIM1222) | Clinical data Use of drugs, emergency and urgent care room visits, hospital admissions within 30 days of illness Cost Data Cost of HD-IIV and SD-IIV Cost of non-prescription and prescription medications Cost of hospitalizations Cost of lost productivity | All lost productivity was estimated from average daily wage for Americans, assumed the number of medical visits was equivalent to number of days of productivity lost |

Chit, 2015b17 USAa Sanofi Pasteur | One influenza season, except premature death (modeled over lifetime) Societal perspective | Model cost-effectiveness of influenza vaccine options for adults over 65 in the US | Adults over 65 years in US | HD-IIV3 SD-IIV3 SD-IIV4 No vaccine | Model-based | Clinical data Absolute and relative effectiveness of vaccine Cost data Costs of vaccine, PCMA influenza, and influenza-related hospitalizations | Assumed that a hospitalization leading up to death was captured in rate of influenza-related hospitalizations Work loss assumed to occur in individuals with influenza Assumed no indirect protection or presenteeism due to influenza AEs of influenza vaccine assumed not to occur |

AE = adverse events; HD = high-dose; IIV3 = trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; IIV4 = quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; PCMA = primary care medically attended; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard dose

- a

First author is from Canada; however the model is on US seniors

Table 5Characteristics of Included Guideline

View in own window

| Intended Users, Target Population | Intervention and Practice Considered | Major Outcomes Considered | Evidence Collection, Selection, and Synthesis | Study Designs and Numbers of Primary Studies Included Intervention and Comparator(s) | Evidence Quality Assessment | Recommendations Development and Evaluation |

|---|

| An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS)National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) Canadian Immunization Guide Chapter on Influenza and Statement on Seasonal Influenza Vaccine for 2018–2019, 20181,18 |

|---|

Health care providers and public health practitioners, policy makers, program planners and the general public with knowledge and interest in immunization and vaccines. Target population of all Canadians | Influenza vaccination for all populations, including high-dose vaccine for adults over 65 | Efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety | Systematic review performed by PHAC or contracted out24 Selection performed in duplicate | Four studies comparing efficacy Update18 added 5 additional studies regarding effectiveness of high-dose influenza vaccine in adults 65 and older | “Remaining articles were assessed with regard to the level of evidence and the quality of the study” | “The overall direction and magnitude of the benefits and harms associated with use of a vaccine are weighed”24 Recommendations and statements of expert advisory committees

- -

National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) - -

Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT)

|

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 6Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses using AMSTAR3

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Chong, 20187 |

|---|

- -

PICO criteria outlined and clear - -

Study selection and data extraction performed independently and in duplicate - -

Included detailed information about included studies, with the exception of follow-up times - -

Conflict of interest discussed (no conflicts)

| - -

No a priori protocol - -

Only two databases searched, with major keywords provided but unclear methodology (no MeSH terms provided) - -

No grey literature searched - -

Limited by English language, no justification provided - -

No list of exclusions - -

No quality appraisal performed, and no risk of bias assessed - -

Bias mentioned briefly in regards to one primary study, but not overall, and effect on results not discussed - -

Substantial heterogeneity in results noted, but effect not discussed - -

Some p-values differing between tables and text - -

Funding source not disclosed

|

| Lee, 20188 |

|---|

- -

PICO criteria outlined and clear - -

Multiple databases searched with search strategy provided in supplementary - -

Included detailed information about included studies’ population, outcome - -

Critical appraisal performed using Down’s and Black checklist - -

Manufacturer funding disclosed - -

Although not explicitly justified, meta-analysis likely appropriate (same population, intervention, comparator) and appropriate methods uses (random effects model) - -

Publication bias assessed using Egger’s test and found to be unlikely, although some tests only performed with two studies included and were likely not necessary - -

Sensitivity analyses performed - -

Heterogeneity addressed and reasons for heterogeneity discussed

| - -

No a priori protocol - -

No list of exclusions - -

Unknown if study selection or data abstraction/extraction performed in duplicate - -

No grey literature searched, no references lists searched, no trial registries searched, no experts consulted - -

Limited by English language, no justification provided - -

One study was eliminated from the meta-analysis due to overlap in populations with another study but unclear why one study was chosen for exclusion over the other (Shay 201726 is a follow-up from Izurieta 2015,27 so likely excluded because of this, but unclear in text) - -

Funding sources of primary studies not detailed - -

P values in meta-analysis do not match confidence intervals - -

Funded by manufacturer of high-dose vaccine

|

| Wilkinson, 20179 |

|---|

- -

A priori protocol registered in PROSPERO - -

PICO criteria outlined and clear - -

Multiple databases searched, hand searching, trial registries searched, with search strategy provided - -

No language restrictions, publication status restrictions, or date restrictions - -

Study selection and screening performed by two reviewers - -

Two reviewers independently abstracted data from studies - -

Risk of bias assessed using Cochrane RoB tool - -

Source of funding and influence for each primary study described, and sensitivity analyses performed between industry funded and ‘other’ funded studies - -

Meta-analysis performed if data statistically and clinically homogenous, with random effects model - -

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses performed by study quality

| - -

Included only RCTs, but no justification provided - -

No exclusion list provided - -

Funding sources extracted from primary studies but not reported on - -

No publication bias analysed

|

PICO = population, intervention, comparator, outcomes; RCT = randomized controlled trial;

Table 7Strengths and Limitations of Clinical Studies using Down’s and Black Checklist4

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Natori, 201810 |

|---|

- -

Hypothesis of study clearly described - -

Main outcomes clearly described - -

Characteristics of patients described - -

Interventions clearly described - -

Main findings clearly described - -

Adverse events reported - -

Actual probability values reported

- -

Subjects representative of entire population from which they were recruited - -

Staff and facilities representative of treatment most patients receive

- -

Attempt made to blind participants to treatment received - -

Attempt made to blind outcome assessors and individual administering the vaccinations - -

Compliance with the intervention likely as it was administered by a separate physician, not by the patient - -

Main outcome measures likely accurate

- -

Patients in intervention and comparator recruited from same population - -

Study subjects randomized to interventions groups - -

Randomized intervention assignment concealed until recruitment complete

- -

Power calculation considered

| - -

Statistical tests used to assess safety outcomes unclear - -

Study powered for immunogenicity and not safety, so unsure if study sufficiently powered to detect a meaningful difference - -

Characteristics of patients LTF not described - -

No adjustment for confounding

|

| Halasa, 201611 |

|---|

- -

Hypothesis of study clearly described - -

Main outcomes clearly described - -

Characteristics of patients described - -

Interventions clearly described - -

Adverse events reported

- -

Subjects representative of entire population from which they were recruited - -

Staff and facilities representative of treatment most patients receive

- -

Attempt made to blind participants to treatment received - -

Attempt made to blind outcome assessors - -

Compliance with the intervention likely as it was administered by a separate nurse, not by the patient - -

Main outcome measures likely accurate - -

Patients in intervention and comparator recruited from same population - -

Study subject randomized to interventions groups - -

Randomized intervention assignment concealed until recruitment complete

| - -

P values not reported (with the exception of one significant finding) - -

Raw numbers not reported, only reported in graphical form with no numerical values attributed to bars - -

Randomization sequence/methodology not detailed - -

Randomization concealment unknown - -

No power calculation performed, low numbers in intervention groups, so unlikely to have had enough power to detect a statistically meaningful difference - -

Individual administering vaccine unblinded - -

Recruitment occurred over two influenza seasons, although vaccine formulation identical, may have been differences in seasonal influenza - -

Did not monitor for influenza symptoms - -

First author recipient of grant support from the manufacturer of high-dose vaccination - -

Manufacturer supported study

|

| Jamshed, 201612 |

|---|

- -

Hypothesis of study clearly described - -

Main outcomes clearly described - -

Characteristics of patients described - -

Interventions clearly described - -

Adverse events reported

- -

Subjects representative of entire population from which they were recruited - -

Staff and facilities representative of treatment most patients receive

- -

Attempt made to blind participants to treatment received - -

Attempt made to blind outcome assessors - -

Compliance with the intervention likely as it was administered by a separate nurse, not by the patient - -

Main outcome measures likely accurate

- -

Patients in intervention and comparator recruited from same population - -

Study subject randomized to interventions groups - -

Patients stratified for randomization by solid tumour or haematological malignancy

| - -

Statistical testing of AEs not clear - -

Raw numbers not reported, only reported in graphical form with no numerical values attributed to bars - -

Only one P value reported for safety outcomes - -

Randomization methodology not clear. “The study pharmacists randomized patients to HD or SD arms” only information provided - -

Baseline patient characteristic apparently tested statistically, but not reported in the text or tables - -

Individual randomizing patient same individual preparing vaccine for injection - -

First author recipient of research support from the manufacturer of high-dose vaccination - -

Manufacturer supported study

|

| McKittrick, 201313 |

|---|

- -

Hypothesis of study clearly described - -

Main outcomes clearly described - -

Characteristics of patients described - -

Interventions clearly described - -

Adverse events reported

- -

Subjects representative of entire population from which they were recruited - -

Staff and facilities representative of treatment most patients receive - -

Attempt made to blind participants to treatment received - -

Attempt made to blind outcome assessors - -

Compliance with the intervention likely as it was administered by a separate nurse, not by the patient - -

Main outcome measures likely accurate - -

Study subject randomized to interventions groups - -

Patients in intervention and comparator recruited from same population - -

Study subject randomized to interventions groups - -

Power calculation performed

| - -

Baseline characteristics not tested statistically - -

Safety outcomes not tested statistically, so unknown if statistically different - -

Manufacturer not involved in study design or analysis - -

Characteristics of patients lost to follow up not described - -

Most patients had undetectable HIV viral load so unable to draw conclusions about vaccine effectiveness for patients with ingoing HIV viremia

|

AE = adverse events; LTF = Loss-to-followup

Table 8Strengths and Limitations of Guidelines using AGREE II6

View in own window

| Item | Guideline |

|---|

| An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS)National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) Canadian Immunization Guide Chapter on Influenza and Statement on Seasonal Influenza Vaccine for 2018–2019, 2018a1,18,19 |

|---|

| Domain 1: Scope and Purpose |

|---|

| 1. The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described. | Y |

| 2. The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described. | Y |

| 3. The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described. | Y |

| Domain 2: Stakeholder Involvement |

|---|

| 4. The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups. | Yb |

| 5. The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought. | N |

| 6. The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. | Y |

| Domain 3: Rigour of Development |

|---|

| 7. Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. | Y |

| 8. The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. | Y |

| 9. The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described. | Y |

| 10. The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. | Nc |

| 11. The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations. | Y |

| 12. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. | Y |

| 13. The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. | N |

| 14. A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. | N/Ad |

| Domain 4: Clarity of Presentation |

|---|

| 15. The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. | Y |

| 16. The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented. | Y |

| 17. Key recommendations are easily identifiable. | Y |

| Domain 5: Applicability |

|---|

| 18. The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application. | N |

| 19. The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice. | Ne |

| 20. The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. | Y |

| 21. The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria. | N |

| Domain 6: Editorial Independence |

|---|

| 22. The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline. | Y |

| 23. Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed. | Y |

- a

Some information is taken from the Canadian Immunization Guide, in which Influenza is a chapter. The Canadian Immunization Guide Influenza chapter has been integrated into the annual Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Statement.

- b

Guideline development groups (referred to as “working groups”) consist of NACI members, liaison members and Public Health Agency of Canada medical and/or epidemiologic specialists. An Influenza Working Group (IWG) was created for the purpose of influenza vaccine recommendations, which likely contained relevant individuals

- c

The IWG reviews the evidence, creates recommendations, and assigns the letters, According to the methods document24 there is not a quantitative process for letter assignment, therefore it is unclear

- d

Recommendations from the Seasonal Influenza Statements are updated yearly

- e

Although there are recommendations within the Canadian Immunization Guide on general vaccination implementation and tools, there are no influenza specific tools in the Influenza chapter for 2017-2018.

Table 9Strengths and Limitations of Economic Studies using the Drummond Checklist5

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Becker, 201615 |

|---|

Study design

- -

The research questions, economic importance of the research question, rationale for choosing alternative programmes or interventions compared are stated. - -

The alternatives being compared are clearly described. The form of economic evaluation used is stated and justified in relation to the questions addressed.

Data collection

- -

The source(s) of effectiveness estimates used are stated - -

The primary outcome measure(s) for the economic evaluation are clearly stated. - -

Methods to value benefits are stated - -

Details of the subjects from whom valuations were obtained were given - -

Productivity changes (if included) are reported separately and relevance of productivity changes to the study question is discussed - -

Currency and price data are recorded and details of currency of price adjustments for inflation or currency conversion are give

Analysis and interpretation of results

- -

Time horizon of costs and benefits is stated. - -

The discount rate(s) is stated. (5%) - -

The approach to sensitivity analysis is given - -

The answer to the study question is given - -

Incremental analysis is reported - -

Conclusions follow from the data reported.

| - -

Some details of the design and results of effectiveness study are given, (e.g. relative efficacy) but many details missing - -

HD-IIV3 vaccine price was estimated from American pricing, not from an official Canadian price (as it was not available) - -

Only 5% of patients within reference RCT were Canadian, although patients found to be homogenous enough to be used as a pooled sample - -

Reference RCT not powered enough for the economic evaluation - -

Assumptions made (such as that wages lost are equivalent to the average daily wage, and that the number of physician visits equivalent to number of days lost [from a US based study]) that may not accurately reflect reality - -

Some conclusions written differently from one another, which possibly could be misleading (e.g., bootstrapped samples for scenario A [all patients] are 89% cost saving [i.e., in the lower two quadrants], and for scenario B [cardio vascular outcomes] are 80% cost saving and effective [i.e., in lower right quadrant]. This may be misleading, and the percentage of samples in the lower right quadrant in scenario A are not reported) - -

Manufacturer supported study, with authors employed by HD-IIV vaccination manufacturer

|

| Raviotta, 201623 |

|---|

Study design

- -

The research questions, economic importance of the research question, rationale for choosing alternative programmes or interventions compared are stated. - -

The alternatives being compared are clearly described - -

The form of economic evaluation used is stated and justified in relation to the questions addressed.

Data collection

- -

The source(s) of effectiveness estimates used are stated - -

The primary outcome measure(s) for the economic evaluation are clearly stated. - -

Productivity changes (if included) are reported separately and relevance of productivity changes to the study question is discussed - -

Currency and price data are recorded and details of currency of price adjustments for inflation or currency conversion are given

Analysis and interpretation of results

- -

Time horizon of costs and benefits is stated. - -

The discount rate(s) is stated. (3%) - -

The approach to sensitivity analysis is given - -

The answer to the study question is given - -

Incremental analysis is reported - -

Conclusions follow from the data reported.

| - -

Assumed mortality from ‘other’ cause not related to vaccine - -

No herd immunity taken into account - -

Price of HD-IIV3 was estimated from average wholesale price - -

Influenza related health care utilization based on published data and not Medicare claims data, so may have underestimated benefit of vaccine - -

US based study may not apply to the Canadian context

|

| Chit, 2015a16 |

|---|

Study design

- -

The research questions, economic importance of the research question, rationale for choosing alternative programmes or interventions compared are stated. - -

The alternatives being compared are clearly described. The form of economic evaluation used is stated and justified in relation to the questions addressed.

Data collection

- -

The source(s) of effectiveness estimates used are stated - -

The primary outcome measure(s) for the economic evaluation are clearly stated. - -

Methods to value benefits are stated - -

Details of the subjects from whom valuations were obtained were given - -

Productivity changes (if included) are reported separately and relevance of productivity changes to the study question is discussed

Analysis and interpretation of results

- -

Time horizon of costs and benefits is stated. - -

The discount rate(s) is stated. (3%) - -

The approach to sensitivity analysis is given - -

The answer to the study question is given - -

Incremental analysis is reported - -

Conclusions follow from the data reported.

| - -

Reference RCT not powered enough for the economic evaluation - -

Assumptions made (such as that wages lost are equivalent to the average daily wage, and that the number of physician visits equivalent to number of days lost [from a US based study]) that may not accurately reflect reality - -

Manufacturer supported study, with authors employed by HD-IIV vaccination manufacturer - -

No adjustment for inflation - -

Some conclusions written differently from one another, which possibly could be misleading (e.g., bootstrapped samples for scenario A [all patients] are 93% cost saving [i.e., in the lower two quadrants], and for scenario B [cardio vascular outcomes] are 94% cost saving and effective [i.e., in lower right quadrant]. This may be misleading, and the percentage of samples in the lower right quadrant in scenario A are not reported) - -

Quality of life data had to be estimated as it was not collected in the reference RCT - -

Long term disability and indirect protection to non-vaccinated individuals not taken into account or able to be estimated - -

US based study may not apply to the Canadian context

|

| Chit, 2015b17 |

|---|

Study design

- -

The research questions, economic importance of the research question, rationale for choosing alternative programmes or interventions compared are stated. - -

The alternatives being compared are clearly described - -

The form of economic evaluation used is stated and justified in relation to the questions addressed.

Data collection

- -

The source(s) of effectiveness estimates used are stated - -

The primary outcome measure(s) for the economic evaluation are clearly stated. - -

Methods to value benefits are stated - -

Details of the subjects from whom valuations were obtained were given - -

Productivity changes (if included) are reported separately and relevance of productivity changes to the study question is discussed

Analysis and interpretation of results

- -

Time horizon of costs and benefits is stated. - -

The discount rate(s) is stated. (3%) - -

The approach to sensitivity analysis is given - -

The answer to the study question is given - -

Incremental analysis is reported - -

Conclusions follow from the data reported.

| - -

No herd immunity taken into account - -

Many assumptions made, simplifying model but may not reflect real-life accurately - -

Studies that vaccine effectiveness based off of derived from NRS, efficacy of SD-IIV4 estimated without trial or study data - -

Manufacturer supported study, with authors employed by HD-IIV3 vaccination manufacturer - -

US based study may not apply to the Canadian context

|

IIV = trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; HD = high dose; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard dose;

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 10Summary of Findings Included Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Chong, 20187 |

|---|

One RCT included relevant to research question Safety HD, intradermal, 2 doses in succession vs. SD IIV3, intramuscular, 1 dose, % of patients (proportion) Local AEs Erythema – 55.3 (63/114) vs. 7 (8/114), P <0.001 Induration – 30.7 (35/114) vs. 7 (8/114), P <0.001 Pruritus – 18.4 (21/114) vs. 1.8 (2/114), P<0.001 [written as “P < 0.001” in table, “P = 0.005” in text] Tenderness – 57.9 (66/114) vs. 24.6 (28/114), P < 0.001 Systemic Fatigue – 10.6 (12/114) vs. 8.8 (10/114), P = 0.13 GI symptoms – 15.8 (18/114) vs. 5.2 (6/114), P = 0.0016 Subjective fever – 4.4 (5/114) vs. 1.8 (2/114), P = 0.45 | The proportion of local adverse events (AEs), such as erythema (P < .001), induration (P < .001), tenderness (P < .001), and pruritus (P = .005), were significantly higher with intradermal IIV3” Page 1809 “In conclusion, BD and HD influenza vaccination strategies seem to hold promise for improving vaccination immunogenicity and were generally well tolerated in SOTRs.” Page 1810

|

| Lee, 20188 |

|---|

Meta-analysis includes 7 studies (one study not included in MA due to population overlap) Influenza related clinical outcomes, HD-IIV3 vs. SD-IIV3, pooled OR (95% CI) Influenza like illness: 0.81 (0.71 to 0.91), P = 0.04 Influenza hospitalization: 0.82 (0.74 to 0.92), P = 0.04 Pneumonia hospitalization: 0.76 (0.67 to 0.86), P = 0.40a Cardiorespiratory hospitalization: 0.82 (0.72 to 0.93), P = 0.49a All-cause hospitalization: 0.91 (0.85 to 0.98), P = 0.02 Post-Influenza mortality: 0.78 (0.51 to 1.18), P = 0.12 All-cause mortality: 0.98 (0.90 to 1.05), P = 0.33 Influenza related clinical outcomes, HD-IIV3 vs. SD-IIV3, pooled relative efficacy or effectiveness (95% CI) Influenza like illness: 19.5% (8.6 to 29.0), P < 0.001 Influenza hospitalization: 17.8% (8.1 to 26.5), P < 0.001 Pneumonia hospitalization: 24.3% (13.9 to 33.4), P < 0.001 Cardiorespiratory hospitalization: 18.2% (6.8 to 28.1), P = 0.002 All-cause hospitalization: 9.1% (2.4 to 15.3), P = 0.009 Post-Influenza mortality: 22.2% (−18.2 to 48.8), P = 0.240 All-cause mortality: 2.5% (−5.2 to 9.5), P = 0.514 Sensitivity analysis – RCTs only Influenza like illness: 24.1% (10.0 to 36.1), P = 0.002 Pneumonia hospitalization: 27.3% (15.3 to 37.6), P < 0.001 All-cause hospitalization: 11.9% (2.0 to 20.7), P = 0.019 All-cause mortality: 4.9% (−6.5 to 15.1), P = 0.381 HD-IIV3 vs. SD-IIV3, (95% CI) All cause hospitalization, pooled ARR: 0.014 (0.001 to 0.028) NNV to prevent all cause hospitalization: 71.4 Sensitivity analysis – RCTs only All cause hospitalization, pooled ARR: 0.019 (0.004 to 0.034) NNV to prevent all cause hospitalization: 52.6 | “In terms of the impact of HD-IIV3 on influenza-associated hospitalizations and deaths, this study highlights the fact that results from multiple randomized and observational studies have consistently shown that HD-IIV3 provides better protection in older adults against influenza and influenza-related hospitalizations compared to SD-IIV3.” Page 441 |

| Wilkinson, 20179 |

|---|

3 studies relevant to research question Laboratory confirmed influenza infection 3 studies, HD vaccine vs. SD vaccine, risk ratio (95% CI)

- -

0.76 (0.65 to 0.90) - -

I2 = 0% - -

24% greater vaccine efficacy in high dose group

“Well matched” vaccine componentsb

- -

0.65 (0.48 to 0.87)

Not “well matchedb vaccine components

- -

0.83 (0.67 to 1.02)

No subgroup analyses performed for influenza infectionNo reported influenza hospitalization or deaths Safety

- -

No trials had any cases of vaccine associated mortality, Guillain-Barre syndrome, or anaphylaxis - -

One trial reported a case of Bell’s Palsy in standard dose group

| “There is limited evidence that the high-dose trivalent, inactivated influenza vaccine in ambulatory, medically stable patients over the age of 65 is associated with decreased rates of laboratory-confirmed influenza infection compared with the standard dose vaccine” page 2780 |

AE = adverse events; ARR = absolute risk reduction; GI = gastrointestinal; IIV3 = trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; HD = high dose; MA = meta-analysis; RCT = randomized controlled trials; SD = standard dose

- a

95% CI appears to be significant, however the P-value in the forest plot is non-significant. This is likely a typo in p-value.

- b

Well matched refers to components of the vaccine matching the seasonal influenza in which they were used

Table 11Summary of Findings of Included Primary Clinical Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Natori, 201823 |

|---|