Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- NRS

Non-Randomized Studies

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- SR

Systematic Review

- TBSA

Total Body Surface Area

Context and Policy Issues

In adults and children the most prevalent burns are from scald injuries obtained in the home from spilling a hot drink.1 Typically, a burn is a result of exposure to a thermal source resulting in tissue damage of measurable depth and size with burn size expressed as percent of total body surface area (TBSA) affected. Intensity and duration of the exposure determines depth of a wound.2 Thermal burns such as scalding or contact burns customarily are small in size but are deep, whereas trauma from fire or flames present at mixed depths and are complicated by adverse events such as inhalation effects that may make breathing difficult.1 Burns affecting greater than 10% TBSA are often from fire or flames.1

The current standard for any burn treatment has been in existence since the 1960’s and includes four domains: removing clothing and jewelry from the affected site; applying cool running water; covering the wound; and then seeking medical help.3 However, the actual burn first aid received is often inaccurate, inadequate, and inconsistent due to a lack of consensus in available information.3 Conflicting evidence exists in the first aid treatment of burns. Current guidelines generally agree that cooling with running water is effective in mitigating cell damage and reducing wound size.2,4,5 Guidelines, however, vary greatly in optimal water-cooling temperature, best method of cooling, and exact duration of cooling.4 As a result, these first aid measures are often poorly initiated when burn trauma occurs.

Additionally, burns affecting greater than 10% TBSA increase the risk of further complications such as hypothermia. Thermoreceptors embedded in the reticular dermis layer of the skin enable temperature regulation, but this regulation can be impaired when the epidermis is damaged by deep partial-thickness burns or full-thickness burns, which affect the reticular dermis.6,7 Cooling burns with water first aid may further increase the patient’s risk of hypothermia.5 The clinical effectiveness of water first aid to cool burns affecting greater than 10% TBSA needs to be addressed.

The objective of this report is to summarize the evidence regarding the clinical effectiveness of cooling thermal burns when total body surface area affected is greater than 10% as well as relevant evidence-based guidelines for cooling thermal burns.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness of cooling thermal burns when total body surface area affected is greater than 10%?

What are the evidence-based guidelines for cooling thermal burns?

Key Findings

No evidence specific to the clinical effectiveness of cooling on burns affecting greater than 10% total body surface area was found. Based on evidence from one non-randomized study that included participants with burns with a total body surface area ranging from five to greater than 25%, the benefit of water first aid was greater in burns with smaller affected total body surface area, especially, medium total body surface area for admission to the intensive care unit. After water first aid, burns with larger total body surface area resulted in a longer hospital length of stay. In-hospital mortality was significantly and linearly associated with total body surface area. The benefit of cooling was greater in burns with smaller total body surface area for graft surgery.

Recommendations regarding cooling acute thermal burns included: stopping the burning process by cooling any major burn or burn exceeding 10% total body surface area for at least twenty minutes; reducing risk of hypothermia by performing first aid, emergency management, and treatment in a warm environment, as well as reducing heat loss by keeping patients covered while exposing burned skin sequentially; and that ice or ice water should not be used due to the risk of hypothermia and impaired perfusion. The included evidence-based guideline further stated that burns affecting greater or equal to 15% total body surface area increase the risk of systemic morbidity and mortality and that burns damage the skin and increase the risk of hypothermia, especially in children.

Overall, the evidence addressing the clinical effectiveness of cooling first aid to treat burns affecting greater than 10% total body surface area is sparse, particularly in children, where the surface area to body volume ratio is greater. Further high quality studies are needed to determine the optimal temperature, duration, and timing of cooling burns as well as the clinical effectiveness of cooling when burns affect greater than 10% of the total body surface area. Additionally, the effect of hypothermia on the relationship between burns and cooling needs to be addressed.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. No filters were applied to limit the retrieval by study type. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2013 and December 9, 2018.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , were duplicate publications, were not published in English, or were published prior to 2013. Guidelines with unclear methodology were also excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included non-randomized study (NRS)8 was assessed using the ROBINS I Tool,9 and the evidence-based guideline6 was assessed with the AGREE II instrument.10 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

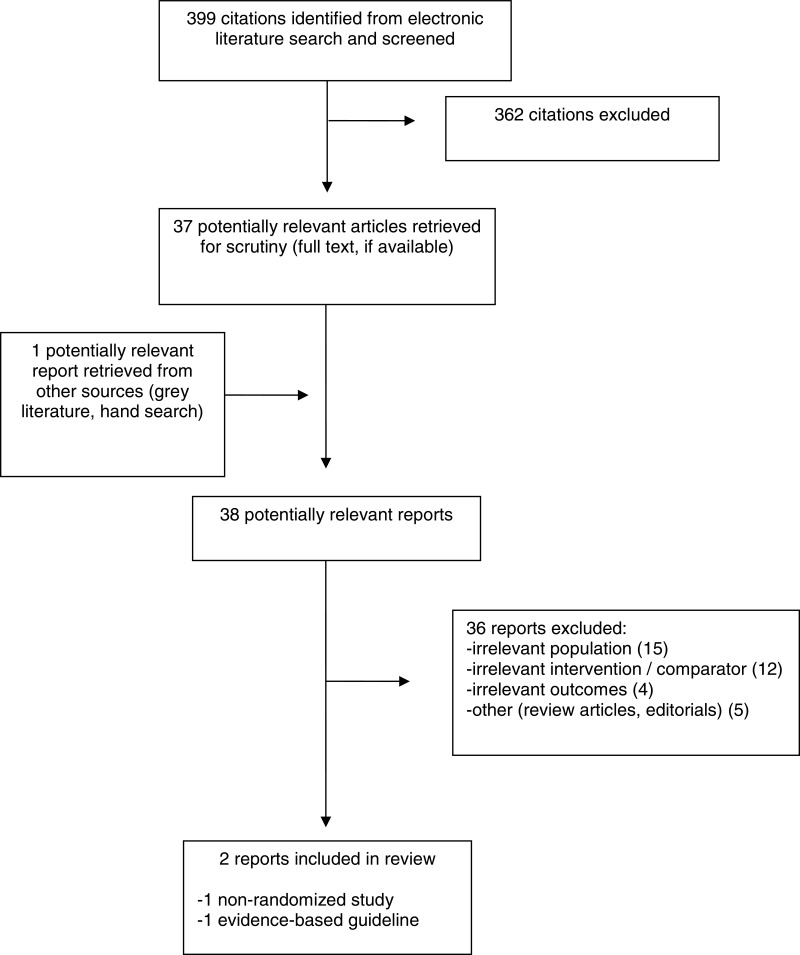

A total of 399 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 362 citations were excluded and 37 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. One potentially relevant publication was retrieved from the grey literature search for full text review. Of these potentially relevant articles, 36 publications were excluded for various reasons, and two publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. These comprised one non-randomized study,8 and one evidence-based guideline.8

Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA11 flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

The non-randomized study, a prospective cohort study, was published in 2016.8

The evidence-based guideline was published in 2018. The DynaMed Plus guideline undertook a systematic search for relevant literature and assessed these using the German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine/German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine expert grading system (DGAI/DIVI) and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). Prior to publication, consensus on phrasing and strength of recommendations is achieved by all editors.6

Country of Origin

The non-randomized study was produced in Australia.8 The evidence-based guideline was produced in the United States.6

Patient Population

The non-randomized study drew data on 2,320 adults with thermal burns (median TBSA of 5.5%, IQR 3 to 10%, and ≥ 25% in 5% of cases) from the Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand (BRANZ).8

The target population for the guideline included patients with major burns.6 Clinical decision-makers are the intended use of the guideline. All first aid recommendations provided a narrative summary of clinical practice guidelines burn management, however, although the methods stated that evidence was graded, none reported ratings of the evidence.6

Interventions and Comparators

The intervention of cooling (water first aid) was examined in the non-randomized study and the guideline and was defined as:

Timing:

Within first three hours post-injury

8

The comparators varied between studies and were defined as:

In the non-randomized study, 68% of participants received cooling water first aid and 97% of those received it within three hours of injury.8

Outcomes

The outcomes varied between studies with no overlap and included:

Stopping the burning process: halt progression of wound depth

6Graft Surgery: wound repair surgery

8Total Hospital Length of Stay (days)

8Admission to intensive care unit.

8

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Additional details regarding the strengths and limitations of included publications are provided in ROBINS I.

Non-Randomized Study

The non-randomized study appropriately controlled for all important confounders which themselves were appropriately measured and documented. Selection of participants into the study was not based on characteristics observed after the start of intervention, which coincides with start of follow-up. Intervention groups were clearly defined, recorded at the start of intervention, and could not have been affected by knowledge of the outcome. Deviations from intended intervention were within what would be expected in usual practice.8 These study characteristics limit bias in: presence of confounding variables; selection of participants; and classification of or deviations from intervention, which therefore, increase confidence in the results of the study.

Outcome data were available for nearly all participants and participants were not excluded due to missing data. Outcome measurement was not likely influenced by knowledge of received intervention, but may be affected by the variety of settings in which the outcome was assessed. However, this effect was likely mitigated by robust estimation of standard errors based upon geographic clustering in all models and by including geographic location in proximity score analyses. Selection of the reported results is not likely based on multiple outcome measurements, multiple analyses, or differing subgroups.8 These study characteristics limit bias due to: missing data; outcome measurement; and selection of reported result, which therefore increase confidence in the results of the study.

Guidelines

The evidence-based guideline clearly described the scope and purpose of the guideline. Stakeholder involvement in development of the guideline included all relevant groups and the target users were clearly defined and incorporated the target users in its development. Recommendations are clearly presented and described the applicability of recommendations but did not assess resource implications. Views of the funding body and competing interests have not likely influenced guideline content.6 These guideline characteristics limit bias and therefore increase confidence in the recommendations of the guideline. However, evidence quality assessments were not reported for the recommendations of interest to this report, which decreases the confidence in these recommendations.

Summary of Findings

Clinical Effectiveness of Cooling Thermal Burns when affected TBSA is greater than 10%

The non-randomized study observed that the benefit of water first aid was greater in burns with smaller TBSA and, especially, medium TBSA for admission to ICU (p<0.001). This study also observed that after water first aid, burns with larger TBSA result in a longer hospital length of stay (p<0.001). This effect may have occurred due to the exclusion of patients who died in-hospital from this analysis, where-in it was possible that cooling increased survival and survival increased length of stay because those who did not survive died within a shorter length of stay. Another possibility was that cooling had side-effects such as hypothermia that extended the length of stay. This possibility was supported by the association of in-hospital mortality with cooling, including a significant linear association with TBSA. Additionally, this study found the benefit of cooling was greater in burns with smaller TBSA for graft surgery (p=0.003).8 It is important to note that the study included those with median TBSA of 5.5%, IQR 3 to 10%, 5% of which had TBSA greater or equal to 25%, thus the results were not limited to those with burns of 10% or greater TBSA.

Guideline

The DynaMed first aid and emergency management guidelines6 call for stopping the burning process by cooling the wound for at least twenty minutes based on any major burn or burn exceeding 10% TBSA. The recommendations state that ice or ice water should not be used due to the risk of hypothermia and impaired perfusion. The guideline states that burns affecting greater or equal to 15% TBSA increase the risk of systemic morbidity and mortality. The damaged epidermis increases the risk of hypothermia, especially in children, therefore, in order to reduce risk of hypothermia, the recommendation is to perform first aid, emergency management, and treatment in a warm environment and reduce heat loss by keeping patients covered while exposing burned skin sequentially. Strength of these recommendations cannot be assessed because no evidence quality assessment for these recommendations was reported.6

Limitations

Evidence specific to burns exceeding more than 10% TBSA is sparse - most information regarding cooling of burns pertained to all burns and contained conflicting data regarding temperature, duration, and timing of cooling as well as the effect of potential adverse events like hypothermia.6–8,12–18

According to both the included citations and those that were not eligible for inclusion due to either non-systematic study methods or examining smaller burns, cooling treatment for burns treatment rarely takes into account treatment that occurs during transport to a hospital or during in patient care in hospital, relying primarily on pre-hospital cooling with first aid often being poorly delivered.3,19–21

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

One non-randomized study8 and one evidence-based guideline6 regarding the cooling of burns were included.

Based on the non-randomized study, it is not possible to draw a firm conclusion regarding the clinical effectiveness of cooling first aid to treat burns affecting greater than 10% TBSA, as not all of those included in the study had burns affecting greater than 10% TBSA.8 The benefit of water first aid was greater in burns with both smaller affected TBSA and especially medium-sized burns for admission to the ICU. After water first aid, burns with larger TBSA result in a longer hospital length of stay. In-hospital mortality was significantly and linearly associated with TBSA. The benefit of cooling was greater in burns with smaller TBSA for graft surgery.8

The included guideline recommends stopping the burning process by cooling any major burn or burn exceeding 10% TBSA for at least twenty minutes. It further states that ice or ice water should not be used due to the risk of hypothermia and impaired perfusion. The guideline states that burns affecting greater or equal to 15% TBSA increase the risk of systemic morbidity and mortality, and that burns damage the skin and increase the risk of hypothermia, especially in children. Reducing risk of hypothermia, performing first aid, and treatment in a warm environment and reduce heat loss by keeping patients covered while exposing burned skin sequentially are highlighted in the guideline. However, strength of these recommendations cannot be assessed because no evidence quality assessment for these recommendations was reported.6

Several studies that were not eligible for inclusion suggested that studies assessing content analysis of available burn first aid information, public education regarding burn first aid, home remedies for treatment of burns, as well as actual first aid technique used found that first aid delivered to burns is often inaccurate, inadequate, and inconsistent due to a lack of consensus in available information.3,19–21 Conflicting evidence exists in the first aid treatment of burns.3,19–21

Consensus statements and guidance was identified that did not follow systematic methods and that generally concerned all burns. Water first aid for treatment of thermal burns was generally defined by included studies as running cool water7,8,12,14,15,17 at a temperature of 15 degrees Celsius7,12,14–16 for 20 minutes6–8,12,14,15,17 over a thermal burn within the first three hours post injury.7,8 Guidance regarding wet pad first aid indicates that it should only be used if running water is unavailable,7,14,15 transport time is greater than one hour,16 or if risk of hypothermia is too high to use running water.16 Similarly, guidance with respect to gel pad first aid indicates that it should only be used if: water is unavailable17 or impractical;17 or transport time is greater than one hour.16 Guidance also indicates ice first aid should not be used,6,7,12–17 and that both the risk of hypothermia and infection should be weighed against the benefits of cooling burns.14,15,18

Further high quality studies are needed to reduce the uncertainty regarding: cooling of major burns in a pediatric population; investigate the optimal temperature, duration, and timing of cooling burns affecting greater than 10% TBSA; assess the association between in-hospital mortality and cooling; as well as examine the the effect of hypothermia on the relationship between burns and cooling.

References

- 1.

Stiles

K. Emergency management of burns: part 1.

Emerg Nurse. 2018;26(1):36–42. [

PubMed: 29701036]

- 2.

Joffe

MD. Emergency care of moderate and severe thermal burns in children. In: Post

TW, ed.

UpToDate. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017:

www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2019 Jan 09.

- 3.

Burgess

JD, Cameron

CM, Cuttle

L, Tyack

Z, Kimble

RM. Inaccurate, inadequate and inconsistent: a content analysis of burn first aid information online.

Burns. 2016;42(8):1671–1677. [

PubMed: 27756588]

- 4.

Varley

A, Sarginson

J, Young

A. Evidence-based first aid advice for paediatric burns in the United Kingdom.

Burns. 2016;42(3):571–577. [

PubMed: 26655279]

- 5.

Rice

Jr.

PL, Orgill

DP. Emergency care of moderate and severe thermal burns in adults. In: Post

TW, ed.

UpToDate. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2018:

www.uptodate.com. Accessed 2019 Jan 09.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 12.

Fong

E. Thermal injury (pediatric): first aid management. Adelaide (AU): The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- 13.

Bitter

CC, Erickson

TB. Management of burn injuries in the wilderness: lessons from low-resource settings.

Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27(4):519–525. [

PubMed: 28029455]

- 14.

The Joanna Briggs Institute. Thermal injury (adults): first aid management. Adelaide (AU): The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2016.

- 15.

Chu

WH. Thermal injury: first aid management. Adelaide (AU): The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2016.

- 16.

Haines

E, Fairbrother

H. Optimizing emergency management to reduce morbidity and mortality in pediatric burn patients.

Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2015;12(5):1–23. [

PubMed: 26011952]

- 17.

- 18.

Singletary

EM, Zideman

DA, De Buck

ED, et al. Part 9: First aid: 2015 international consensus on first aid science with treatment recommendations.

Circulation. 2015;132(16 Suppl 1):S269–311. [

PubMed: 26472857]

- 19.

Sahu

SA, Agrawal

K, Patel

PK. Scald burn, a preventable injury: analysis of 4306 patients from a major tertiary care center.

Burns. 2016;42(8):1844–1849. [

PubMed: 27436508]

- 20.

Bennett

CV, Maguire

S, Nuttall

D, et al. First aid for children’s burns in the US and UK: an urgent call to establish and promote international standards.

Burns. 2018. [

PubMed: 30266196]

- 21.

Sadeghi Bazargani

H, Fouladi

N, Alimohammadi

H, Sadeghieh Ahari

S, Agamohammadi

M, Mohamadi

R. Prehospital treatment of burns: a qualitative study of experiences, perceptions and reactions of victims.

Burns. 2013;39(5):860–865. [

PubMed: 23523224]

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Primary Clinical Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Clinical Outcomes, Length of Follow-Up |

|---|

| Wood 2016, Australia and New Zealand8 | Prospective cohort study | Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand (BRANZ)

| Intervention:

Comparator:

| Patient related outcomes:

Graft surgery In-hospital mortality

Health system (cost) outcomes:

|

TBSA = Total Body Surface Area, IQR = Inter-Quartile Range, ICU = Intensive Care Unit

Table 3Characteristics of Included Guidelines

View in own window

| Intended Users, Target Population | Intervention and Practice Considered | Major Outcomes Considered | Evidence Collection, Selection, and Synthesis | Evidence Quality Assessment | Recommendations Development and Evaluation | Guideline Validation |

|---|

| DynaMed Plus 20186 |

|---|

Intended Users Clinical decision-makers Target Population Patients with major burns | Interventions:

|

Hypothermia Impaired perfusion

| Relevant literature is systematically searched but exact methodology is unclear. At least two reviewers assessed relevant literature (≥ 1 with methodological expertise and ≥ 1 with content domain expertise). | Quality of evidence was rated using DGAI/DIVI and GRADE | Strength of recommendations was rated using DGAI/DIVI and GRADE. Prior to publication, consensus on phrasing and strength of recommendations is achieved by all editors. | ≥ 1 editor with methodological expertise who is not involved in the other stages verifies strength of recommendations and supporting evidence. |

DGAI/DIVI = German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine/German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine expert grading system, GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4Strengths and Limitations of Non-Randomized Study using ROBINS I Tool9

View in own window

| Item | Non-Randomized Studies |

|---|

| Wood 20168 |

|---|

| Domain 1: Confounding |

|---|

| 1. There is no potential for confounding of the effect of intervention in this study. The study can be considered to be at low risk of bias due to confounding. No further items are assessed. | No |

2. The analysis was not based on splitting participants’ follow up time according to intervention received. Baseline confounding only assessed. | No |

| 3. Intervention discontinuations or switches were not likely to be related to factors that are prognostic for the outcome. Baseline confounding only assessed. | No |

| 4. Baseline confounding: The authors used an appropriate analysis method that controlled for all the important confounding domains. | Yes |

| 5. Baseline confounding: If applicable, confounding domains that were adjusted for were measured validly and reliably by the variables available in this study. | Yes |

| 6. Baseline confounding: The authors controlled for any post-intervention variables that could have been affected by the intervention. | Yes |

| 7. Baseline and time-varying confounding: The authors used an appropriate analysis method that adjusted for all the important confounding domains and for time-varying confounding. | N/A |

| 8. Baseline and time-varying confounding: If applicable, confounding domains that were adjusted for were measured validly and reliably by the variables available in this study. | N/A |

| Domain 2: Selection of participants into the study |

|---|

| 9. Selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis) was not based on participant characteristics observed after the start of intervention. | Yes |

| 10. If applicable, the post-intervention variables that influenced selection were not likely to be associated with intervention. | N/A |

| 11. If applicable, the post-intervention variables that influenced selection were not likely to be influenced by the outcome or a cause of the outcome. | N/A |

| 12. Start of follow-up and start of intervention coincide for most participants. | Yes |

| 13. If applicable, adjustment techniques were used that are likely to correct for the presence of selection biases. | N/A |

| Domain 3: Classification of Interventions |

|---|

| 14. Intervention groups were clearly defined. | Yes |

| 15. The information used to define intervention groups was recorded at the start of the intervention. | Yes |

| 16. Classification of intervention status could not have been affected by knowledge of the outcome or risk of the outcome. | Yes |

| Domain 4: Intended Interventions |

|---|

| 17. Assignment to intervention: There were no deviations from the intended intervention beyond what would be expected in usual practice. | Yes |

| 18. Assignment to intervention: If applicable, these deviations from intended intervention were balanced between groups and unlikely to have affected the outcome. | N/A |

| 19. Adherence to intervention: Important co-interventions were balanced across intervention groups. | N/A |

| 20. Adherence to intervention: The intervention was implemented successfully for most participants. | N/A |

| 21. Adherence to intervention: Study participants adhered to the assigned intervention regimen. | N/A |

| 22. Adherence to intervention: If applicable, an appropriate analysis was used to estimate the effect of starting and adhering to the intervention. | N/A |

| Domain 5: Missing Data |

|---|

| 23. Outcome data were available for all, or nearly all, participants. | Yes |

| 24. Participants were not excluded due to missing data on intervention status. | Yes |

| 25. Participants were not excluded due to missing data on other variables needed for the analysis. | Yes |

| 26. If applicable, the proportion of participants and reasons for missing are data similar across interventions. | Yes |

| 27. If applicable, there is evidence that results were robust to the presence of missing data. | Yes |

| Domain 6: Measurement of Outcomes |

|---|

| 28. The outcome measure could not have been influenced by knowledge of the intervention received. | Yes |

| 29. Outcome assessors were not aware of the intervention received by study participants. | No |

| 30. The methods of outcome assessment were comparable across intervention groups. | No |

| 31. Any systematic errors in measurement of the outcome were not related to intervention received. | Yes |

| Domain 7: Selection of the Reported Result |

|---|

| 32. The reported effect estimate is unlikely to be selected, on the basis of the results, from multiple outcome measurements within the outcome domain. | Yes |

| 33. The reported effect estimate is unlikely to be selected, on the basis of the results, from multiple analyses of the intervention-outcome relationship. | Yes |

| 34. The reported effect estimate is unlikely to be selected, on the basis of the results, from different subgroups. | Yes |

Table 5Strengths and Limitations of Guideline using AGREE II

View in own window

| Item | Guideline |

|---|

| DynaMed Plus 20186 |

|---|

| Domain 1: Scope and Purpose | |

|---|

| 1. The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described. | Yes |

| 2. The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described. | Yes |

| 3. The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described. | Yes |

| Domain 2: Stakeholder Involvement | |

|---|

| 4. The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups. | Yes |

| 5. The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought. | Yes |

| 6. The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. | Yes |

| Domain 3: Rigour of Development | |

|---|

| 7. Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. | Yes |

| 8. The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. | Unclear |

| 9. The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described. | Yes |

| 10. The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. | Yes |

| 11. The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations. | Yes |

| 12. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. | Yes |

| 13. The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. | Yes |

| 14. A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. | Yes |

| Domain 4: Clarity of Presentation | |

|---|

| 15. The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. | Yes |

| 16. The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented. | Yes |

| 17. Key recommendations are easily identifiable. | Yes |

| Domain 5: Applicability | |

|---|

| 18. The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application. | Yes |

| 19. The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice. | Yes |

| 20. The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. | No |

| 21. The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria. | Yes |

| Domain 6: Editorial Independence | |

|---|

| 22. The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline. | Yes |

| 23. Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed. | Yes |

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Authors’ Conclusions

Table 6Summary of Findings of Included Primary Clinical Study

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Authors’ Conclusion |

|---|

| Wood 20168 |

|---|

Cooling:

68% patients received cooling prior to admission

Patient related outcomes:

Graft surgery

13% reduction in probability of graft surgery associated with cooling (from 0.537 to 0.070, p=0.014) Probability increases linearly with increasing age and TBSA (OR=1.06, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.11, p=0.032) The benefit of water first aid is greater in burns with smaller TBSA (water first aid and TBSA interact, OR=1.04, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.07, p=0.003)

In-hospital mortality

Association with cooling (OR=0.77, p=0.013) Significant linear association with TBSA (OR=1.09, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.13, p<0.001) The benefit of water first aid is greater at older ages (water first aid and age interact, OR=1.03, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.06, p=0.035)

Health system (cost) outcomes:

Total hospital OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval, LOS in days

18% reduction in probability of LOS associated with cooling from (from 12.9 to 10.63 days, p=0.001) Probability increases non-linearly with increasing TBSA (mean standardized TBSA OR=0.358, 95% CI 0.268 to 0.449, p<0.001, spline transformation 1 OR=1.60, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.96, p<0.001, spline transformation 2 OR=-0.049, 95% CI −0.118 to 0.021, p=0.170) After water first aid, burns with larger TBSA result in longer OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval, LOS (OR=0.20, 95% CI 0.008 to 0.032, p=0.001)

Admission to ICU

48% reduction in probability of ICU admission associated with cooling (0.175 from to 0.084, p<0.001) Probability increases non-linearly with increasing TBSA (mean standardized TBSA OR=2.26, 95% CI 1.84 to 2.78, p<0.001, spline transformation OR=1.32, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.51, p<0.001) The benefit of water first aid is greater in burns with smaller TBSA and, especially, medium TBSA (water first aid and TBSA interact, OR=1.03, 95% CI 0.999 to 1.06, p=0.062)

“All outcomes except death showed a dose-response relationship with the duration of first aid.” (p. 2) | “This study suggests that there are significant patient and health system benefits from cooling water first aid, particularly if applied for up to 20 minutes. The results of this study estimate the effect size of post-burn first aid and confirm that efforts to promote first aid knowledge are not only warranted, but provide potential cost savings.” (p. 2) “This study has confirmed the magnitude of benefit from first aid after burn and emphasised the parameters of water cooling to achieve a significantly reduced need for surgical intervention, length of stay and ICU admission. Further studies with a larger dataset are needed to confirm or refute the association with risk of death.” (p. 12) |

TBSA = Total Body Surface Area, OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval, LOS = Length of Stay, ICU = Intensive Care Unit

Table 7Summary of Recommendations in Included Guideline

View in own window

| Recommendations | Strength of Evidence and Recommendations |

|---|

| DynaMed Plus 20186 |

|---|

Major Burns Definition:

Fourth-degree burns Third-degree burns (full-thickness)

Except patients 10 to 50 years of age with burns affecting < 1% TBSA that do not involve their face, hands, perineum, genitals, feet, or cross a major joint

Second-degree burns (partial-thickness)

Patients < 10 years of age with burns affecting > 5% TBSA Patients > 50 years of age with burns affecting > 5% TBSA ○Patients 10 to 50 years of age with burns affecting > 10% TBSA Burns affecting a patient’s face, hands, perineum, genitals, feet, or cross a major joint

Considerations:

Treatment Overview, First Aid and Emergency Management

Effective burn first aid for major burns or burns affecting > 10% TBSA involves stopping the burning process and cooling the wound:

Cooling (water first aid): stops burning process and cools wound

Ice or ice water first aid: should not be used

May cause hypothermia May impair perfusion

| Not reported. |

TBSA = Total Body Surface Area

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Cooling for thermal burns: clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2019 Jan. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.