1. Introduction

Whole-body bathing or showering with a skin antiseptic to prevent surgical site infections (SSI) is a usual practice before surgery in settings where it is affordable. The aim is to make the skin as clean as possible by removing transient flora and some resident flora. Chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) 4% combined with a detergent or in a triclosan preparation is generally used for this purpose1,2. Preoperative showering with antiseptic agents is a well-accepted procedure for reducing skin microflora3–5, but it is less clear whether this procedure leads to a lower incidence of SSI4,5. A cause for concern is the potential for patient hypersensitivity and allergic reactions to CHG are not uncommon6. However, the most relevant question is whether preoperative bathing or showering with an antiseptic soap is more effective than plain soap to reduce the occurrence of SSI.

Several organizations have issued recommendations regarding preoperative bathing. The care bundles proposed by the United Kingdom (UK) High impact intervention initiative and Health Protection Scotland recommend bathing with soap prior to surgery7,8. The Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland recommends bathing on the day of surgery or before the procedure with soap9. The United States of America (USA) Institute of Healthcare Improvement bundle for hip and knee arthroplasty recommends preoperative bathing with CHG soap10. Finally, the UK-based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend bathing to reduce the microbial load, but not necessarily SSI. In addition, NICE states that the use of antiseptics is inconclusive in preventing SSI and that soap should be used11.

The purpose of this systematic review is to assess the effectiveness of preoperative bathing or showering with antiseptic compared to plain soap and to determine if these agents should be recommended for surgical patients to prevent SSI. The use of CHG cloths for antiseptic preoperative bathing is also addressed, but with a separate PICO question.

2. PICO questions

Is preoperative bathing using an antiseptic soap more effective in reducing the incidence of SSI in surgical patients when compared to bathing with plain soap?

Population: inpatients and outpatients of any age undergoing surgical operations (any type of procedure)

Intervention: bathing with an antiseptic soap

Comparator: bathing with plain soap

Outcomes: SSI, SSI-attributable mortality

Is preoperative bathing with CHG-impregnated cloths more effective in reducing the incidence of SSI in surgical patients when compared to bathing with antiseptic soap?

Population: inpatients and outpatients of any age undergoing surgical operations (any type of procedure)

Intervention: preoperative bathing with no-rinse and use of 2% CHG-impregnated cloths

Comparator: bathing with antiseptic soap

Outcomes: SSI, SSI-attributable mortality

3. Methods

The following databases were searched: Medline (PubMed); Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and WHO regional medical databases. The time limit for the review was between 1 January 1960 and 15 August 2014. Based on a Cochrane Review on the topic12, relevant studies published prior to 1990 were included due to the extremely limited number of trials that met the inclusion criteria when using the time limit of 1990, which was usually applied to the systematic reviews performed for the WHO guidelines for the prevention of SSI. Language was restricted to English, French and Spanish. A comprehensive list of search terms was used, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (Appendix 1)

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved references for potentially relevant studies. The full text of all potentially eligible articles was obtained and then reviewed independently by two authors for eligibility based on inclusion criteria. Duplicate studies were excluded.

The two authors extracted data in a predefined evidence table (Appendix 2) and critically appraised the retrieved studies. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool to assess the risk of bias of randomized controlled studies (RCTs)13 (Appendix 3a) and the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies14 (Appendix 3b). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or after consultation with the senior author, when necessary.

Meta-analyses of available comparisons were performed using Review Manager version 5.3 as appropriate15 (Appendix 4). Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted and pooled for each comparison with a random effects model. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (GRADE Pro software)16 was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence (Appendix 5).

4. Study selection

Flow chart of the study selection process

5. Summary of the findings and quality of the evidence

Findings related to PICO question 1: preoperative bathing or showering with antiseptic soap vs. plain soap

Nine17–25 studies, including 717–23 RCTs, were identified with an SSI outcome comparing preoperative bathing or showering with antiseptic soap vs. plain soap. Included patients were adults undergoing several types of surgical procedures (for example, general, gynaecological, orthopaedic, urological, vascular reconstructive, plastic, breast cancer and hepatobiliary surgery). Studies included elective clean, clean-contaminated and implant surgery. Of note, no written instructions were provided to patients in the control group in most studies. This may have potentially resulted in less thorough washing than in the intervention group. All identified studies used CHG as the antiseptic soap.

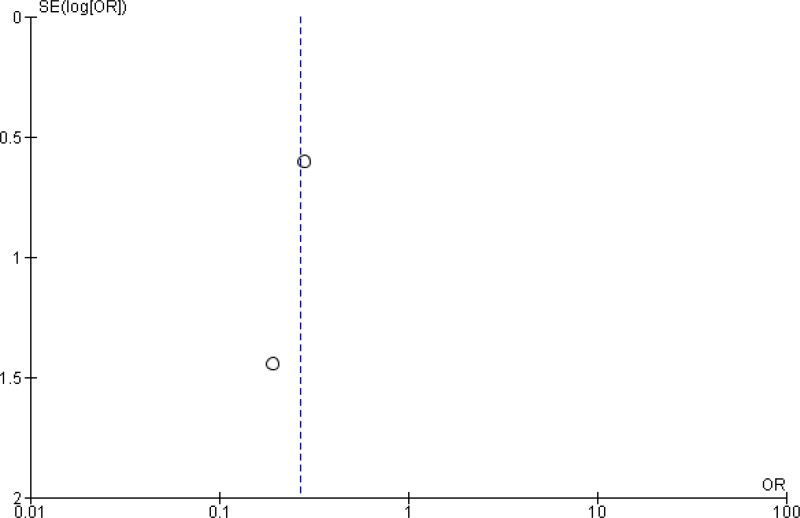

Among the 7 RCTs, 6 studies17,18,20–23 showed no statistically significant difference between bathing with soap containing CHG vs. bathing with plain soap. One study19 reported some effect of bathing with antiseptic soap. A meta-analysis of the 7 RCTs (Appendix 4, ) showed no statistically significant difference between the effect of antiseptic soap and plain soap bathing on SSI (OR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.80–1.04). In addition, the meta-analysis of the two observational studies24,25 showed a similar result (OR: 1.10; 95% CI: 0.87–1.38) (Appendix 4, ).

The quality of the evidence for this comparison was moderate for the RCTs and very low for the observational studies (Appendix 5).

Findings related to PICO question 2: preoperative bathing with CHG-impregnated cloths

Three observational studies investigating the effectiveness of bathing with CHGimpregnated cloths were identified with SSI as the outcome. No RCTs were found on this topic. The following 2 comparisons were identified.

- 1.

CHG-impregnated cloths vs. CHG soap

One prospective cohort study26 compared bathing with CHG 2% cloths vs. CHG 4% antiseptic soap in a population of surgical patients undergoing general, vascular and orthopaedic procedures. The results showed that bathing with CHG-impregnated cloths may have some benefit compared to CHG 4% soap (OR: 0.32; 95% CI: 0.13–0.77) (Appendix 4, ).

- 2.

CHG-impregnated cloths vs. no washing

Two other prospective studies compared bathing twice preoperatively with 2% CHGimpregnated cloths vs. no preoperative bathing in a population of orthopaedic patients. These 2 studies were conducted by the same investigators; one reviewed SSI rates in hip arthroplasties27 and the other reviewed knee arthroplasties28. In both studies, there was no real control group as the comparison was made with a group of patients who did not comply with instructions to bathe with the CHG cloths preoperatively, rather than patients assigned to a predefined control group. A meta-analysis of the studies showed that there might be a significant benefit in using the CHG cloths vs. no use of cloths (OR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.09–0.79).

The quality of the evidence for these comparisons was very low (Appendix 5).

In conclusion, the available evidence can be summarized as follows.

- -

PICO question 1: Preoperative bathing or showering with CHG antiseptic soap vs. plain soap

Overall, a moderate quality of evidence shows that preoperative bathing with CHG soap has neither benefit nor harm in reducing the SSI rate when compared to plain soap.

- -

PICO question 2: Preoperative bathing with CHG-impregnated cloths

Very low quality evidence shows that preoperative bathing with 2% CHG-impregnated cloths may be beneficial in reducing the SSI rate when compared to either bathing with CHG soap or no preoperative bathing. No RCTs were found on this topic.

6. Other factors considered in the review of studies

The systematic review team identified the following other factors to be considered.

Potential harms

The use of antiseptics for preoperative bathing may reduce the incidence of SSI, which can be an expensive and complicated condition to treat. Possible concerns include potential antibiotic resistance with the continued use of antimicrobial agents and adverse events, such as allergic reactions.

Despite its widespread use, reported side-effects from CHG use have been few. These have included delayed reactions, such as contact dermatitis and photosensitivity, toxicity as a result of inadvertent application to the ear with access to the inner ear through a perforated tympanic membrane and hypersensitivity reactions in very rare cases, such as anaphylactic shock6. In the included studies, few adverse events were recorded. Byrne and colleagues17 found that although 9/1754 and 10/1735 patients from the CHG and plain soap groups, respectively, experienced mild skin irritation, there was no evidence of a true allergic reaction. Veiga and colleagues23 reported no incidence of adverse events in any of the 150 enrolled patients. Exclusion criteria for individual studies may have eliminated also some of the population that may have experienced allergic reactions in prospective studies by excluding patients with known skin sensitivities and allergies.

Values and preferences

It was acknowledged that most patients with access to water would bathe prior to surgery. Patients would tend to carry out the procedures that they were told to do by the professional health care worker. It was highlighted that it is important for the patient to be informed of best clinical practice.

Resource use

Cloths may provide the benefits of using a preoperative antiseptic without the use of water, which may improve compliance with preoperative bathing protocols. However, it is also important to consider the monetary expense of using agents such as CHGimpregnated cloths vs. traditional bathing and/or bathing with antiseptic solutions. Lynch and colleagues20 conducted a cost-effectiveness study including 3482 general surgical patients who showered 3 times preoperatively with either CHG detergent (n=1744) or detergent without CHG (n=1738). They found that the average hospital cost of both non-infected and infected patients was higher in the CHG group and concluded that preoperative whole-body washing with a CHG detergent is not a cost-effective treatment for reducing wound infection. However, it is important to note that this study consisted of predominantly clean surgical procedures in which the risk of SSI is lower. Future studies investigating the cost of SSI prevention in contaminated surgery may find that the cost of treating SSI is more of a burden than providing antiseptic preoperative bathing.

Some studies investigating the effectiveness of CHG-impregnated cloths evaluated also the economic impact of their use. Bailey and colleagues found that cloths were the most effective and economical strategy, based on their cost and overall effectiveness for SSI prevention. Therefore, it was concluded that the routine distribution of bathing kits was economically beneficial for the prevention of SSI29. Similarly, Kapadia and colleagues calculated a potential annual saving ranging from US$ 0.78–3.18 billion by decreasing health care costs, primarily due to the reduction of the incidence of SSI30.

7. Key uncertainties and future research priorities

The systematic review team identified the following key uncertainties and future research priorities.

The lack of new evidence suggests that practices are already established and accepted in the medical community. In the light of emerging patterns of resistance developing with antiseptic use31 and the potential for adverse events6, it may be important for future research to investigate whether the use of antiseptics is pertinent and to re-evaluate the efficacy of non-medicated soap or no bathing vs. preoperative bathing with antiseptics in a variety of settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Safety associated with the use of a non-rinse application of CHG should be evaluated also. Current evidence suggests that CHG may not have a significant benefit or harm compared to plain soap in preventing SSI. Cost and availability may also pose a problem in low-resource hospital settings. Additional studies quantifying SSI as an outcome, rather than bacterial skin colonization, should be considered to further elucidate the effect of preoperative washing with antiseptic solutions, including CHG-impregnated cloths. Future PICO questions should include: (1) does preoperative bathing help reduce the incidence of SSI in clean-contaminated or contaminated surgical procedures? (2) Does preoperative bathing with an antiseptic detergent vs. non-medicated bar soap reduce the incidence of SSI in patients undergoing clean-contaminated or contaminated surgical procedures?

The lack of high-quality RCTs indicates a need for further research on the efficacy of preoperative bathing with CHG-impregnated cloths for the prevention of SSI. In addition, most procedures in all 3 included studies were orthopaedic operations, many of which did not observe superficial SSI as an outcome. Overall, the available studies had a limited number of events and the quality of evidence was very low.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search terms

Medline (via PubMed)

(“surgical wound infection”[Mesh] OR surgical site infection* [TIAB] OR “SSI” OR “SSIs” OR surgical wound infection* [TIAB] OR surgical infection*[TIAB] OR postoperative wound infection* [TIAB] OR postoperative wound infection* [TIAB] OR wound infection*[TIAB]) OR ((“preoperative care”[Mesh] OR “preoperative care” OR “pre-operative care” OR “perioperative care”[Mesh] OR “perioperative care” OR “perioperative care” OR perioperative OR intraoperative OR “perioperative period”[Mesh] OR “intraoperative period”[Mesh]) AND (“infection”[Mesh] OR infection [TIAB])) AND (“skin preparation” [TIAB] OR “skin preparations” [TIAB] OR skin prep [TIAB] OR “baths”[Mesh] OR bath*[TIAB] OR cleaning OR cleansing)

EMBASE

(‘surgical wound infection’ OR ‘surgical wound infection’ OR surgical AND site AND infection* OR ‘ssi’ OR ‘ssis’ OR surgical AND (‘wound’) AND infection* OR surgical AND infection* OR ‘post operative’ AND (wound) AND infection* OR postoperative AND (‘wound’) AND infection* OR ‘wound’ OR wound AND infection* OR (‘preoperative care’ OR ‘pre-operative care’ OR’ perioperative care’ OR ‘perioperative care’ OR ‘peri-operative care’ OR perioperative OR intraoperative OR ‘perioperative period’ OR ‘perioperative period’ OR ‘intraoperative period’ AND (‘infection’)) AND (‘skin preparation’ OR ‘skin preparations’ OR skin AND prep OR bath*) AND [1960–2014]/py

CINAHL

(‘surgical wound infection’/exp OR ‘surgical wound infection’ OR surgical AND site AND infection* OR ‘ssi’ OR ‘ssis’ OR surgical AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection*) OR (surgical AND infection*) OR (‘post operative’ AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection*) OR (postoperative AND (‘wound’/exp OR wound) AND infection*) OR (‘wound’/exp OR wound AND infection*) OR (‘preoperative care’/exp OR ‘preoperative care’ OR ‘pre-operative care’ OR‘perioperative care’/exp OR ‘perioperative care’ OR ‘peri-operative care’ OR perioperative OR intraoperative OR ‘perioperative period’/exp OR ‘perioperative period’ OR ‘intraoperative period’/exp OR ‘intraoperative period’ AND (‘infection’ OR ‘infection’/exp OR infection)) AND (‘skin preparation’ OR ‘skin preparations’ OR ‘skin’/exp OR (skin AND prep) OR ‘baths’/exp OR ‘baths’ OR bath*)

Cochrane CENTRAL

((ssi) OR (surgical site infection) OR (surgical site infections) OR (wound infection) OR (wound infections) OR (postoperative wound infection)) AND bathing

WHO Global Health Library

((ssi) OR (surgical site infection) OR (surgical site infections) OR (wound infection) OR (wound infections) OR (postoperative wound infection)) AND (bathing OR bath OR shower)

- ti:

title;

- ab:

abstract.

Appendix 2. Evidence table

Appendix 2a. Studies related to bathing with an antiseptic soap vs. plain soap

Download PDF (377K)

Appendix 2b. Studies on chlorhexidine-impregnated cloths

Download PDF (310K)

Appendix 3. Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

Appendix 3a. Studies related to preoperative bathing with an antiseptic soap vs. plain soap

Risk of bias in the included randomized controlled studies (Cochrane Collaboration tool)

View in own window

| RCT Author, year, reference | Study design | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Participants and personnel blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|

| Byrne, 199217 | RCT | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Earnshaw, 198918 | RCT | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH |

| Hayek, 198819 | RCT | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | HIGH | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | HIGH |

| Lynch, 199220 | RCT | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | UNCLEAR |

| Randall, 198321 | RCT | LOW | UNCLEAR | HIGH | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Rotter, 198822 | RCT | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Veiga, 200823 | RCT | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

Risk of bias in the included cohort studies (Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale)

View in own window

| Other controlled studies Author, year, reference | Representativeness of cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start | Comparability of cohorts | Assessment of outcome | Follow-up long enough | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts |

|---|

| Ayliffe, 198324 | B (*) | B | B (*) | B | A (*) | B (*) | B | D |

| Leigh, 198325 | B (*) | A (*) | A (*) | B | - | B (*) | A (*) | C |

Appendix 3b. Risk of bias assessment of studies related to preoperative bathing with CHG–impregnated cloths (Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale)

View in own window

| Author, year, reference | Representativeness of cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start | Comparability of cohorts | Assessment of outcome | Follow-up long enough | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts |

|---|

| Graling, 201326 | B* | B | A* | A* | - | B* | A* | B* |

| Johnson, 201027 | B* | A* | C | A* | Age(*) | B* | A* | D |

| Johnson, 201328 | B* | A* | C | A* | Age(*)

Other(*) | B* | A* | D |

CHG: chlorhexidine gluconate

References

- 1.

Derde

LP, Dautzenberg

MJ, Bonten

MJ. Chlorhexidine body washing to control antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in intensive care units: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:931–9. [

PMC free article: PMC3351589] [

PubMed: 22527065]

- 2.

Koburger

T, Hubner

NO, Braun

M, Siebert

J, Kramer

A. Standardized comparison of antiseptic efficacy of triclosan, PVP-iodine, octenidine dihydrochloride, polyhexanide and chlorhexidine digluconate. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1712–9. [

PubMed: 20551215]

- 3.

Garibaldi

RA. Prevention of intraoperative wound contamination with chlorhexidine shower and scrub. J Hosp Infec

1988;11(Suppl. B):5–9. [

PubMed: 2898503]

- 4.

Kaiser

AB, Kernodle

DS, Barg

NL, Petracek

MR. Influence of preoperative showers on staphylococcal skin colonization: a comparative trial of antiseptic skin cleansers. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:35–8. [

PubMed: 3337574]

- 5.

Seal

LA, Paul-Cheadle

D. A systems approach to preoperative surgical patient skin preparation. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:57–62. [

PubMed: 15057196]

- 6.

Krautheim

AB, Jermann

TH, Bircher

AJ. Chlorhexidine anaphylaxis: case report and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:113–6. [

PubMed: 15153122]

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

Owens

P, McHugh

S, Clarke-Moloney

M, et al. Improving surgical site infection prevention practices through a multifaceted educational intervention. Ir Med J. 2015;108:78–81. [

PubMed: 25876299]

- 10.

How to guide: prevent surgical site infection for hip and knee arthroplasty. Cambridge (MA): Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2012.

- 11.

Leaper

D, Burman-Roy

S, Palanca

A, Cullen

K, Worster

D, Gautam-Aitken

E, et al. Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337. [

PubMed: 18957455]

- 12.

Webster

J, Osborne

S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD004985. [

PubMed: 22972080]

- 13.

Higgins

JP, Altman

DG, Gotzsche

PC, Jüni

P, Moher

D, Oxman

AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [

PMC free article: PMC3196245] [

PubMed: 22008217]

- 14.

Wells

GA, Shea

B, O’Connell

D, Peterson

J, Welch

V, Losos

M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Toronto: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2014 (

http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp, accessed 13 May 2016).

- 15.

The Nordic Cochrane Centre TCC. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration

2014.

- 16.

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool. Summary of findings tables, health technology sssessment and guidelines. GRADE Working Group, Ontario: McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc.; 2015 (

http://www.gradepro.org, accessed 5 May 2016).

- 17.

Byrne

DJ, Napier, A., Cuschieri, A.

Prevention of postoperative wound infection in clean and potentially contaminated surgery. A prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Surg Res Comm. 1992;12:43–52.

- 18.

Earnshaw

JJ, Berridge

DC, Slack

RC, Makin

GS, Hopkinson

BR. Do preoperative chlorhexidine baths reduce the risk of infection after vascular reconstruction?

Europ J Vasc Surg. 1989;3:323–6. [

PubMed: 2670608]

- 19.

Hayek

LJ, Emerson

JM. Preoperative whole body disinfection-a controlled clinical study. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11(Suppl. B):15–9. [

PubMed: 2898499]

- 20.

Lynch

W, Davey

PG, Malek

M, Byrne

DJ, Napier

A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the use of chlorhexidine detergent in preoperative whole-body disinfection in wound infection prophylaxis. J Hosp Infect. 1992;21:179–91. [

PubMed: 1353510]

- 21.

Randall

PE, Ganguli

LA, Keaney

MG, Marcuson

RW. Prevention of wound infection following vasectomy. Br J Urology. 1985;57:227–9. [

PubMed: 3986461]

- 22.

Rotter

ML. A placebo-controlled trial of the effect of two preoperative baths or showers with chlorhexidine detergent on postoperative wound infection rates. J Hosp Infect. 1988;12:137–8. [

PubMed: 2905721]

- 23.

Veiga

DF, Damasceno

CA, Veiga-Filho

J, Figueiras

RG, Vieira

RB, Garcia

ES, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of chlorhexidine showers before elective plastic surgical procedures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;30:77–9. [

PubMed: 19046051]

- 24.

Ayliffe

GA, Noy

MF, Babb

JR, Davies

JG, Jackson

J. A comparison of preoperative bathing with chlorhexidine-detergent and non-medicated soap in the prevention of wound infection. J Hosp Infect. 1983;4:237–44. [

PubMed: 6195236]

- 25.

Leigh

DA, Stronge

JL, Marriner

J, Sedgwick

J. Total body bathing with ‘Hibiscrub’ (chlorhexidine) in surgical patients: a controlled trial. J Hosp Infect. 1983;4:229–35. [

PubMed: 6195235]

- 26.

Graling

PR, Vasaly

FW. Effectiveness of 2% CHG cloth bathing for reducing surgical site infections. AORN J. 2013;97:547–51. [

PubMed: 23622827]

- 27.

Johnson

AJ, Daley

JA, Zywiel

MG, Delanois

RE, Mont

MA. Preoperative chlorhexidine preparation and the incidence of surgical site infections after hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:98–102. [

PubMed: 20570089]

- 28.

Johnson

AJ, Kapadia

BH, Daley

JA, Molina

CB, Mont

MA. Chlorhexidine reduces infections in knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2013;26:213–8. [

PubMed: 23288739]

- 29.

Bailey

RR, Stuckey

DR, Norman

BA, Duggan

AP, Bacon

KM, Connor

DL, et al. Economic value of dispensing home-based preoperative chlorhexidine bathing cloths to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol. 2011;32:465–71. [

PMC free article: PMC3386002] [

PubMed: 21515977]

- 30.

Kapadia

BH, Johnson

AJ, Daley

JA, Issa

K, Mont

MA. Pre-admission cutaneous chlorhexidine preparation reduces surgical site infections in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;28:490–3. [

PubMed: 23114192]

- 31.

Paulson

DS. Efficacy evaluation of a 4% chlorhexidine gluconate as a full-body shower wash. Am J Infect Control. 1993;21:205–9. [

PubMed: 8239051]