e-Therapy Interventions for the Treatments of Patients with Depression: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Authors

Chuong Ho and Melissa Severn.Context and Policy Issues

One in five Canadians experiences a mental health problem, with approximately 8% of adults having major depression at some time in their lives.1 Depression can include symptoms such as sadness, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts and places a mental burden on patients, their families, and caregivers.1 Treatment strategies for depression often include clinical care with antidepressant medication (i.e., treatment as usual – TAU), as well as a number of psychotherapies, with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) being the most used evidence-based strategy.2

In its traditional form, CBT requires the individual to work face-to-face with their therapist to identify, challenge, and evaluate the thoughts that maintain the depressive mood. Despite the positive impact that psychological interventions might have on the reduction of depression, its burden includes that it is not always practical to deliver those interventions to the community due to limited health care resources, especially in rural areas where access to health professionals may be lacking. E-therapy, by using information technology such as internet- and mobile-based interventions to deliver CBT, has been introduced as a treatment option for depression, with the hope of improving access to treatment, reducing time constraints, and reducing costs.3,4 The format and terminology of e-therapy is quite diverse, ranging from computer-delivered psychotherapies (cCBT), internet-delivered CBT (iCBT), web-based CBT (wCBT) or online-based CBT (oCBT), and the distinction between these strategies is not obvious, and often have overlapping components.5,6 In general, these treatment modalities include structured self-help using online written materials, and/or audio/video files for the patient to use without assistance (self-help), or with assistance from therapists by phone, video or emails (therapist-guided). Therapist guidance could be synchronous (the therapist and the patient are speaking or interacting in real time), or asynchronous (the communication is not in real time).

This Rapid Response report aims to review the comparative effectiveness of therapist-guided e-therapy interventions versus other options for the treatment of adult patients with depression.

Research Question

What is the clinical effectiveness of e-therapy for the treatment of patients with depression?

Key Findings

Evidence from a small number of systematic reviews (SRs) and small size randomized controlled trials (RCTs) consistently showed that therapist-guided e-therapy was superior to no treatment, wait list, or TAU in reducing depressive symptoms on patients with depression and major depressive disorder. Therapist-guided e-therapy was found to be equivalent to standard face-to-face CBT for patients with MDD, and the combination of e-therapy and TAU was equivalent to TAU alone in patients with depression.

Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including Medline via Ovid, PsycINFO via Ovid, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials. The search was also limited to English language documents published between Jan 1, 2015 and Apr 18, 2018.

Rapid Response reports are organized so that the evidence for each research question is presented separately.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Selection Criteria.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in Table 1, they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2015. Studies that examined e-therapy in general without separating therapist-guided and pure self-help strategies, or studies that examined only e-therapy without therapist’s guidance, were excluded. Trials that were included in a reported systematic review (SR) were excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included systematic reviews and clinical trials were critically appraised using AMSTAR II,7 and Downs and Black8 instruments, respectively. Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

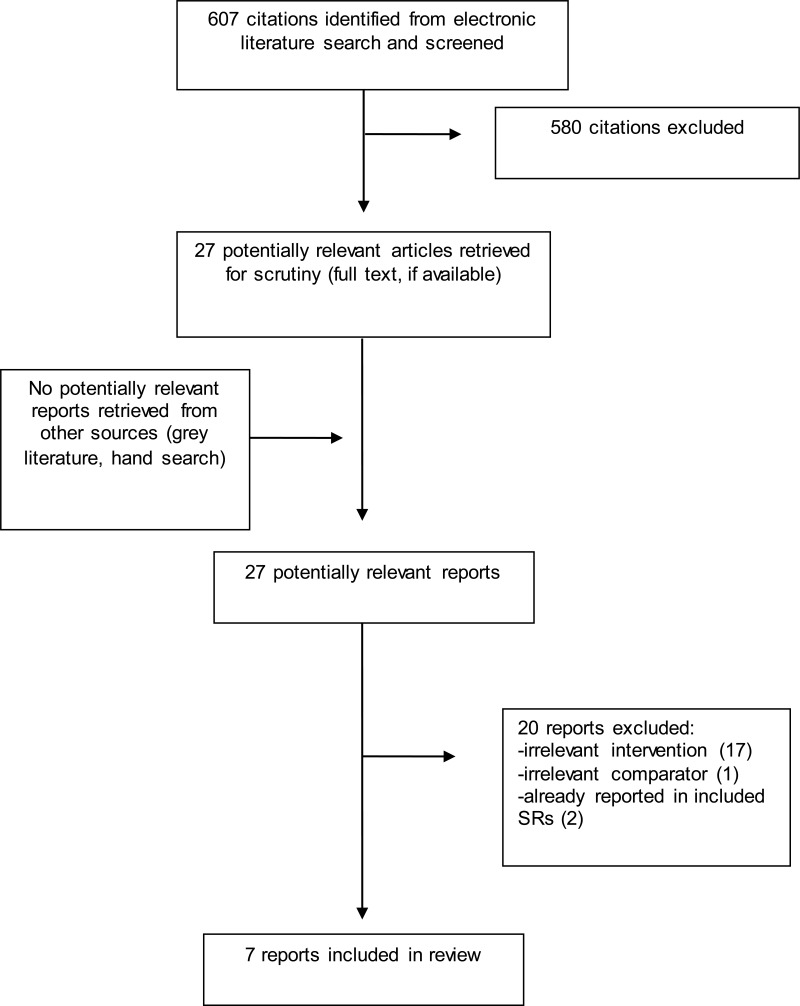

A total of 607 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 580 citations were excluded and 27 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. No potentially relevant publication was retrieved from the grey literature search. Of these potentially relevant articles, 20 publications were excluded for various reasons, while seven publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of Study Characteristics

A detailed summary of the included studies is provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Three SRs with meta-analysis,9–11 and four randomized clinical trials12–15 were included in the review. One SR performed literature search until 2016 and included four relevant RCTs (total eight studies),9 one SR performed literature search until 2016 and included 29 RCTs,10 one SR performed literature search until 2015 and included 14 RCTs.11 All included clinical trials are RCTs. Two trials were single center studies,12,14 and two were multicenter studies.13,15 One RCT had a non-inferiority hypotheses – with the non-inferiority assumption being that the expected difference between the intervention and comparator would be a small to moderate effect.13

Country of Origin

Two SRs9,10 were performed in Ireland, one SR11 and two RCTs12,13 were conducted in the US, one RCT14 in Canada and New Zealand, and one RCT15 took place in Germany.

Patient Population

One SR9 and two RCTs12,14 included patients with depression, one SR included patients with mild to moderate depression,11 one SR10 and one RCT13 included patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), and one RCT included patients with recurrent MDD.15 Comorbid mental health conditions and severity of depression were not reported.

Interventions and Comparators

E-therapy in all included studies was defined as therapy delivered under any online format that covered the core of CBT. One SR compared cCBT to no treatment, wait list, and treatment as usual (TAU) which did not include standard face-to-face CBT.9 One SR compared oCBT to no treatment, wait list, TAU, and standard face-to-face CBT.10 One SR11 and one RCT12 compared iCBT to wait list. One RCT compared cCBT to standard face-to-face CBT.13 One RCT compared wCBT plus usual care to usual care alone.14 One RCT compared iCBT to TAU. Two RCTs had synchronous therapist contact,12,15 and two RCTs did not specify the type of contact.13,14 E-therapy lasted eight weeks in one RCT,12 12 weeks in two RCTs,14,15, and 16 weeks in one RCT.13

Outcomes

All three SRs reported difference in post-treatment depressive symptoms between the two groups based on various rating scales for depression.9–11 Two RCTs12,14 reported difference in post-treatment symptoms determined by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores (PHQ-9), one RCT13 reported difference in post-treatment symptoms determined by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), and one RCT reported the number of “well” and “unwell” weeks based on Psychiatric Status Rating (PSR) of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE).15 Authors did not report clinically meaningful differences for the outcome scales. Dropout rate (completion rate) was reported in one RCT.13

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Details of the strengths and limitations of the included studies are summarized in Appendix 3.

The included SRs9–11 provided an a priori design and performed a systematic literature search. Procedures for the independent duplicate selection and data extraction of studies were in place, a list of included studies and characteristics were provided, a list of excluded studies was not provided. Quality assessment of the included studies was performed and used in formulating conclusions in one SRs,9 and not performed in the remaining two.10,11 Publication bias was assessed in two SRs,10,11 and not assessed in one, which may mean that unpublished studies with less favorable findings may be missing from the body of reviewed studies.9 All SRs were based mainly on RCTs which were heterogeneous with respect to the interventions examined (e.g., components and length of e-therapy, amount and type of therapist’s support), which may affect the accuracy and reliability of the findings.

The included clinical trials12–15 were all RCTs, the hypotheses were clearly described, the method of selection from the source population and representation were described, losses to follow-up were reported, main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings were clearly described, and estimates of random variability and actual probability values were provided. Patients and assessors were not blinded to treatment assignment in three trials which may have impacted the objectivity of the outcomes assessments,12–14 while patients were blinded in one trial.15 Two trials13,14 performed calculations to determine that the trial was powered to detect a clinically important effect, and two trials did not perform such a calculation.12,15 Overall, the included studies had good internal validity. The generalizability of the findings to patients with depression or MDD who also had other comorbid mental health disorders may be limited.

Summary of Findings

Details of the findings of the included studies are provided in Appendix 4.

What is the clinical effectiveness of e-therapy for the treatment of patients with depression?

For adult patients with depression

Two SRs9,11 and two RCTs12,14 examined the efficacy of therapist-guided e-therapy in adults with depression. In general, therapist-guided e-therapy moderately reduced depressive symptoms compared to no treatment, wait list, or TAU. The combination of e-therapy and TAU lead to similar outcomes to TAU alone. Dropout rate was larger in iCBT group than in the wait list group in one trial.

The author of one SR found that therapist-guided cCBT9 (use of a computer program or mobile app that covers core methods of CBT) reduced post-treatment depressive symptoms better than no treatment, wait list, or TAU; the difference between the two groups was statistically significant, and the effect of cCBT was found to be moderate. Findings from another SR11 and one RCT(that included synchronous therapist contact)12 found that therapist-guided iCBT (use of internet-based computer programs to deliver CBT materials via text, video, audio) reduced post-treatment depressive symptoms better than wait-list. In both studies, the difference between the two groups was statistically significant, with the effect of iCBT being moderate in the SR11 and large in the RCT.12 Dropout rate was found to be larger in the iCBT group than in the wait list in the RCT.12 The authors of the SRs and RCT concluded that the implementation of therapist-guided e-therapy lead to a better reduction of depressive symptoms in adult patients than no treatment, wait list, or TAU, and that e-therapy may be an effective option for individuals unable or unwilling to access standard face-to-face CBT.

One RCT14 compared the efficacy of therapist-guided wCBT (use of weekly emails, text messages and telephone contact) combined with TAU, and TAU alone. It was not clear whether therapist contact was synchronous or asynchronous. Findings showed that changes from baseline values in depressive symptoms were not statistically significant between the two groups. The authors concluded that therapist-guided wCBT was feasible in the treatment of patients with depression.

For adult patients with major depressive disorder (MDD)

One SR10 and two RCTs13,15 examined the efficacy of therapist-guided e-therapy in adults with MDD. In general, e-therapy lead to better improvements in depression compared to no treatment, to wait list, and to TAU, and provided similar outcomes to standard face-to-face CBT. Completion rate was similar between cCBT and standard face-to-face CBT as reported in one trial.

The author of one SR10 found that therapist-guided oCBT (use of an online written materials, and/or audio/video files) reduced post-treatment depressive symptoms better than no treatment, wait list, TAU and standard face-to-face CBT together. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant, and the effect of oCBT was found to be moderate. When oCBT was compared to standard face-to-face CBT alone, the difference was not statistically significant. The authors concluded that oCBT was superior to no treatment, to wait list, and to TAU and was equivalent to standard face-to-face CBT in patients with MDD.

One RCT13 compared the efficacy of therapist-guided cCBT to standard face-to-face CBT. It was not clear whether therapist contact was synchronous or asynchronous. Findings showed that both treatment modalities lead to large and similar reduction in depressive symptoms compared to baseline. Completion rate and remission rate were also similar between the two groups. The authors concluded that therapist-guided cCBT was non-inferior to standard face-to-face CBT in the treatment of patients with MDD.

One RCT15 compared the efficacy of therapist-guided iCBT to TAU. Therapist contact was synchronous. Findings showed that the time (in weeks) that the patients were unwell was similar between the two groups. The authors concluded that therapist-guided iCBT was not superior to TAU in patients with MDD.

Limitations

Evidence on therapist-guided e-therapy for the treatment of adults with depression was based mainly on reviews of small size RCTs which may lack the power to detect clinically important effects. The accuracy of estimates from SRs was affected by the heterogeneity in the e-therapy treatments, lack of details on the components of e-therapy strategies, and undetermined amount and type of therapist support (e.g., telephone, email). Together with the lack of details on synchronicity of therapist contact in the included SRs, this is a major limitation that affects the precision of the findings conclusions. In some studies, the use of a waitlist as a comparator instead of an active treatment comparator might have led to an overestimate of the treatment effect of e-therapy. Since the included studies did not include or did not report the whether they included a military, paramilitary, or veteran population, the generalizability to this population is unclear.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Evidence from the included studies showed that implementation of therapist-guided e-therapy may lead to a larger reduction of depressive symptoms in adult patients with depression and MDD than no treatment, wait list, or TAU. Therapist-guided e-therapy is likely equivalent to standard face-to-face CBT for patients with MDD, and the combination of e-therapy and TAU was found to be equivalent to TAU alone in patients with depression. It is unclear whether these results generalize to a military, paramilitary, or veteran population.

The majority of studies on e-therapy for the treatment of depression examined the efficacy of the intervention in general, not separating therapist-guided from pure self-help, and were therefore not included in our review. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) has revised its 2009 guidelines and issued the 2016 guidelines for the treatment of adult patients MDD.16 The guidelines recommended “First-line psychological treatment recommendations for acute MDD include cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and behavioural activation (BA). Second-line recommendations include computer-based and telephone-delivered psychotherapy” (p 524). Despite the recommendations and the potential of e-therapy for the treatment of depression, its use seems to be lagging in clinical routine practice. Trying to explain this, one study17 found the three most important determinants for its implementation in routine care are: “(1) the acceptance of eMH (eMentalHealth) concerning expectations and preferences of patients and professionals about receiving and providing eMH in routine care, (2) the appropriateness of eMH in addressing patients’ mental health disorders, and (3) the availability, reliability, and interoperability with other existing technologies such as the electronic health records” (p 1). This is supported by findings from studies that found that patients with depression experience cCBT as predominantly positive,18 and that a decrease in score at post-treatment assessment is associated with greater odds of adhering to the intervention.19

While this review did not do an in-depth search or analysis of cost-effectiveness studies, some cost information was reported and from a healthcare provider perspective, therapist-guided e-therapy was found to be likely cost-effective for MDD relative to no treatment, wait list, TAU, and standard face-to-face CBT in the United Kingdom, Australian, and Dutch contexts.10 However, therapist-guided e-therapy are not considered cost-effective compared to wait list or TAU for depression in the Netherlands or Germany.20 With the threshold for cost-effectiveness generally based on the healthcare budget available, the generalization of these findings to a Canadian context is limited.

While it is likely that therapist-guided e-therapy interventions are effective, larger comparative RCTs with consistent reporting, and performed in a Canadian context would further confirm the potential to alleviate the mental and economic impact of depression.

References

- 1.

- Fast facts about mental illness [Internet]. Toronto: Canadian Mental Health Association; 2013. [cited 2018 Apr 26]. Available from: https://cmha

.ca/about-cmha /fast-facts-about-mental-illness - 2.

- Lebow J. Overview of psychotherapies. In: Post TW, editor. UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 26]. Available from: www

.uptodate.com Subscription required. - 3.

- Aboujaoude E, Salame W, Naim L. Telemental health: A status update. World Psychiatry [Internet]. 2015 Jun [cited 2018 Apr 20];14(2):223–30. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles /PMC4471979/pdf/wps0014-0223.pdf - 4.

- Cuijpers P, Kleiboer A, Karyotaki E, Riper H. Internet and mobile interventions for depression: Opportunities and challenges. Depress Anxiety. 2017 Jul;34(7):596–602. [PubMed: 28471479]

- 5.

- Ebert DD, Cuijpers P, Munoz RF, Baumeister H. Prevention of Mental Health Disorders Using Internet- and Mobile-Based Interventions: A Narrative Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Front Psychiatr [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 20];8:116. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles /PMC5554359/pdf/fpsyt-08-00116.pdf [PMC free article: PMC5554359] [PubMed: 28848454] - 6.

- Schroder J, Berger T, Westermann S, Klein JP, Moritz S. Internet interventions for depression: new developments. Dialogues Clin Neurosci [Internet]. 2016 Jun [cited 2018 Apr 20];18(2):203–12. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles /PMC4969707/pdf/DialoguesClinNeurosci-18-203.pdf [PMC free article: PMC4969707] [PubMed: 27489460] - 7.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ [Internet]. 2017;358:j4008. Available from: http://www

.bmj.com/content/bmj/358/bmj .j4008.full.pdf [PMC free article: PMC5833365] [PubMed: 28935701] - 8.

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health [Internet]. 1998 Jun;52(6):377–84. Available from: http://www

.ncbi.nlm.nih .gov/pmc/articles /PMC1756728/pdf/v052p00377.pdf [PMC free article: PMC1756728] [PubMed: 9764259] - 9.

- Wells MJ, Owen JJ, McCray LW, Bishop LB, Eells TD, Brown GK, et al. Computer-Assisted Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Depression in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018 Mar 1;20. [PubMed: 29570963]

- 10.

- Ahern E, Kinsella S, Semkovska M. Clinical efficacy and economic evaluation of online cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert rev. 2018 Feb;pharmacoecon. outcomes res.. 18(1):25–41. [PubMed: 29145746]

- 11.

- Sztein DM, Koransky CE, Fegan L, Himelhoch S. Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy delivered over the Internet for depressive symptoms: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2017 Jan 1. [PubMed: 28696153]

- 12.

- Forand NR, Barnett JG, Strunk DR, Hindiyeh MU, Feinberg JE, Keefe JR. Efficacy of Guided iCBT for Depression and Mediation of Change by Cognitive Skill Acquisition. Behav Ther. 2018 Mar;49(2):295–307. [PMC free article: PMC5853137] [PubMed: 29530267]

- 13.

- Thase ME, Wright JH, Eells TD, Barrett MS, Wisniewski SR, Balasubramani GK, et al. Improving the Efficiency of Psychotherapy for Depression: Computer-Assisted Versus Standard CBT. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 1;175(3):242–50. [PMC free article: PMC5848497] [PubMed: 28969439]

- 14.

- Hatcher S, Whittaker R, Patton M, Miles WS, Ralph N, Kercher K, et al. Web-based Therapy Plus Support by a Coach in Depressed Patients Referred to Secondary Mental Health Care: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment Health [Internet]. 2018 Jan 23 [cited 2018 Apr 20];5(1):e5, 2018. Available from: http://mental

.jmir.org /article/download/mental_v5i1e5/2 [PMC free article: PMC5801511] [PubMed: 29362207] - 15.

- Kordy H, Wolf M, Aulich K, Burgy M, Hegerl U, Husing J, et al. Internet-Delivered Disease Management for Recurrent Depression: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychother Psychosom [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Apr 20];85(2):91–8. Available from: http://www

.zora.uzh.ch /id/eprint/128181/1 /Kordy_etal_2016_SUMMIT.pdf [PubMed: 26808817] - 16.

- Parikh SV, Quilty LC, Ravitz P, Rosenbluth M, Pavlova B, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 2. Psychological Treatments. Can J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Sep [cited 2018 Apr 20];61(9):524–39. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4994791/pdf/10 .1177 _0706743716659418.pdf [PMC free article: PMC4994791] [PubMed: 27486150] - 17.

- Vis C, Mol M, Kleiboer A, Buhrmann L, Finch T, Smit J, et al. Improving Implementation of eMental Health for Mood Disorders in Routine Practice: Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitating Factors. JMIR Ment Health [Internet]. 2018 Mar 16 [cited 2018 Apr 20];5(1):e20, 2018. Available from: http://mental

.jmir.org /article/viewFile/mental_v5i1e20/2 [PMC free article: PMC5878369] [PubMed: 29549072] - 18.

- Rost T, Stein J, Lobner M, Kersting A, Luck-Sikorski C, Riedel-Heller SG. User Acceptance of Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2017 Sep 13 [cited 2018 Apr 20];19(9):e309. Available from: http://www

.jmir.org/article /download/jmir_v19i9e309/2 [PMC free article: PMC5617907] [PubMed: 28903893] - 19.

- Castro A, Lopez-Del-Hoyo Y, Peake C, Mayoral F, Botella C, Garcia-Campayo J, et al. Adherence predictors in an Internet-based Intervention program for depression. Cognitive Behav Ther. 2018 May;47(3):246–61. [PubMed: 28871896]

- 20.

- Kolovos S, van Dongen JM, Riper H, Buntrock C, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, et al. Cost effectiveness of guided Internet-based interventions for depression in comparison with control conditions: An individual-participant data meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety [Internet]. 2018 Mar [cited 2018 Apr 20];35(3):209–19. Available from: https://www

.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/pmc/articles /PMC5888145/pdf/DA-35-209.pdf [PMC free article: PMC5888145] [PubMed: 29329486]

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2

Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews.

Table 3

Characteristics of Included Clinical Studies.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4

Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses using AMSTAR II.

Table 5

Strengths and Limitations of Randomized Controlled Trials using Downs and Black.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Author’s Conclusions

Table 6

Summary of Findings of Included Studies.

About the Series

Version: 1.0

Suggested citation:

e-Therapy Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Depression. Ottawa: CADTH; 2018 May. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.

The copyright and other intellectual property rights in this document are owned by CADTH and its licensors. These rights are protected by the Canadian Copyright Act and other national and international laws and agreements. Users are permitted to make copies of this document for non-commercial purposes only, provided it is not modified when reproduced and appropriate credit is given to CADTH and its licensors.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/