Context and Policy Issues

One in five Canadians experiences a mental health problem, with approximately 8% of adults having major depression at some time in their lives.1 Depression can include symptoms such as sadness, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts and places a mental burden on patients, their families, and caregivers.1 Treatment strategies for depression often include clinical care with antidepressant medication (i.e., treatment as usual – TAU), as well as a number of psychotherapies, with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) being the most used evidence-based strategy.2

In its traditional form, CBT requires the individual to work face-to-face with their therapist to identify, challenge, and evaluate the thoughts that maintain the depressive mood. Despite the positive impact that psychological interventions might have on the reduction of depression, its burden includes that it is not always practical to deliver those interventions to the community due to limited health care resources, especially in rural areas where access to health professionals may be lacking. E-therapy, by using information technology such as internet- and mobile-based interventions to deliver CBT, has been introduced as a treatment option for depression, with the hope of improving access to treatment, reducing time constraints, and reducing costs.3,4 The format and terminology of e-therapy is quite diverse, ranging from computer-delivered psychotherapies (cCBT), internet-delivered CBT (iCBT), web-based CBT (wCBT) or online-based CBT (oCBT), and the distinction between these strategies is not obvious, and often have overlapping components.5,6 In general, these treatment modalities include structured self-help using online written materials, and/or audio/video files for the patient to use without assistance (self-help), or with assistance from therapists by phone, video or emails (therapist-guided). Therapist guidance could be synchronous (the therapist and the patient are speaking or interacting in real time), or asynchronous (the communication is not in real time).

This Rapid Response report aims to review the comparative effectiveness of therapist-guided e-therapy interventions versus other options for the treatment of adult patients with depression.

Research Question

What is the clinical effectiveness of e-therapy for the treatment of patients with depression?

Key Findings

Evidence from a small number of systematic reviews (SRs) and small size randomized controlled trials (RCTs) consistently showed that therapist-guided e-therapy was superior to no treatment, wait list, or TAU in reducing depressive symptoms on patients with depression and major depressive disorder. Therapist-guided e-therapy was found to be equivalent to standard face-to-face CBT for patients with MDD, and the combination of e-therapy and TAU was equivalent to TAU alone in patients with depression.

Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including Medline via Ovid, PsycINFO via Ovid, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to limit retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials. The search was also limited to English language documents published between Jan 1, 2015 and Apr 18, 2018.

Rapid Response reports are organized so that the evidence for each research question is presented separately.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2015. Studies that examined e-therapy in general without separating therapist-guided and pure self-help strategies, or studies that examined only e-therapy without therapist’s guidance, were excluded. Trials that were included in a reported systematic review (SR) were excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included systematic reviews and clinical trials were critically appraised using AMSTAR II,7 and Downs and Black8 instruments, respectively. Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

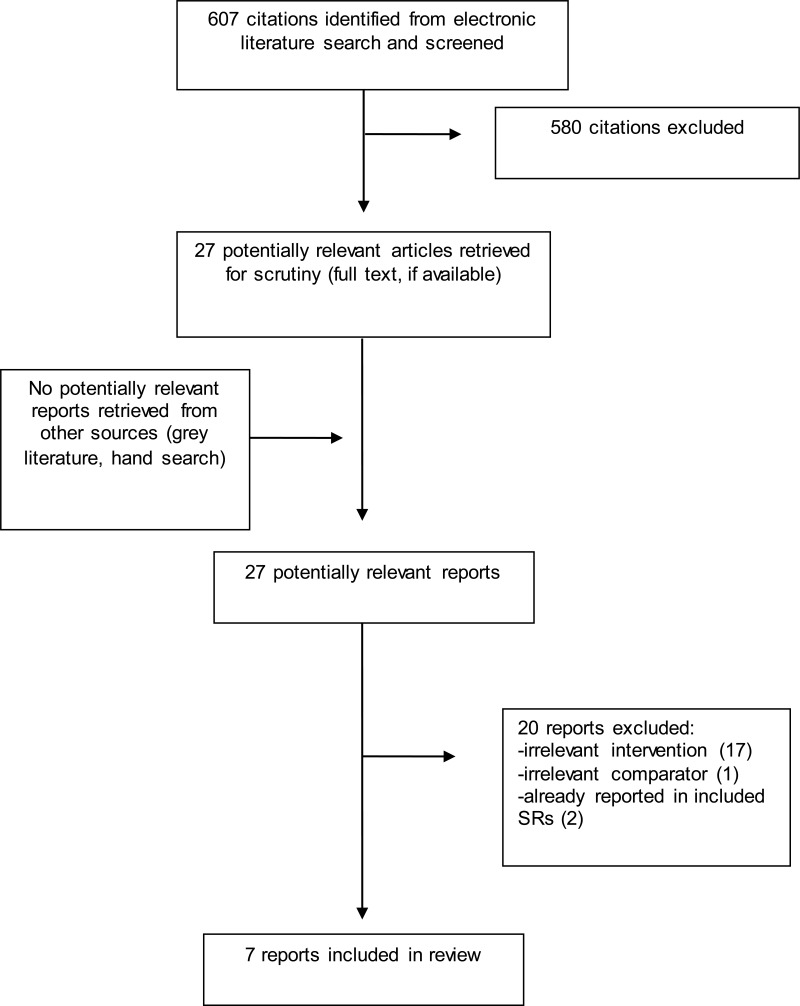

A total of 607 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 580 citations were excluded and 27 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. No potentially relevant publication was retrieved from the grey literature search. Of these potentially relevant articles, 20 publications were excluded for various reasons, while seven publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection.

Summary of Study Characteristics

A detailed summary of the included studies is provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

Three SRs with meta-analysis,9–11 and four randomized clinical trials12–15 were included in the review. One SR performed literature search until 2016 and included four relevant RCTs (total eight studies),9 one SR performed literature search until 2016 and included 29 RCTs,10 one SR performed literature search until 2015 and included 14 RCTs.11 All included clinical trials are RCTs. Two trials were single center studies,12,14 and two were multicenter studies.13,15 One RCT had a non-inferiority hypotheses – with the non-inferiority assumption being that the expected difference between the intervention and comparator would be a small to moderate effect.13

Country of Origin

Two SRs9,10 were performed in Ireland, one SR11 and two RCTs12,13 were conducted in the US, one RCT14 in Canada and New Zealand, and one RCT15 took place in Germany.

Patient Population

One SR9 and two RCTs12,14 included patients with depression, one SR included patients with mild to moderate depression,11 one SR10 and one RCT13 included patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), and one RCT included patients with recurrent MDD.15 Comorbid mental health conditions and severity of depression were not reported.

Interventions and Comparators

E-therapy in all included studies was defined as therapy delivered under any online format that covered the core of CBT. One SR compared cCBT to no treatment, wait list, and treatment as usual (TAU) which did not include standard face-to-face CBT.9 One SR compared oCBT to no treatment, wait list, TAU, and standard face-to-face CBT.10 One SR11 and one RCT12 compared iCBT to wait list. One RCT compared cCBT to standard face-to-face CBT.13 One RCT compared wCBT plus usual care to usual care alone.14 One RCT compared iCBT to TAU. Two RCTs had synchronous therapist contact,12,15 and two RCTs did not specify the type of contact.13,14 E-therapy lasted eight weeks in one RCT,12 12 weeks in two RCTs,14,15, and 16 weeks in one RCT.13

Outcomes

All three SRs reported difference in post-treatment depressive symptoms between the two groups based on various rating scales for depression.9–11 Two RCTs12,14 reported difference in post-treatment symptoms determined by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores (PHQ-9), one RCT13 reported difference in post-treatment symptoms determined by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), and one RCT reported the number of “well” and “unwell” weeks based on Psychiatric Status Rating (PSR) of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE).15 Authors did not report clinically meaningful differences for the outcome scales. Dropout rate (completion rate) was reported in one RCT.13

Summary of Critical Appraisal

Details of the strengths and limitations of the included studies are summarized in Appendix 3.

The included SRs9–11 provided an a priori design and performed a systematic literature search. Procedures for the independent duplicate selection and data extraction of studies were in place, a list of included studies and characteristics were provided, a list of excluded studies was not provided. Quality assessment of the included studies was performed and used in formulating conclusions in one SRs,9 and not performed in the remaining two.10,11 Publication bias was assessed in two SRs,10,11 and not assessed in one, which may mean that unpublished studies with less favorable findings may be missing from the body of reviewed studies.9 All SRs were based mainly on RCTs which were heterogeneous with respect to the interventions examined (e.g., components and length of e-therapy, amount and type of therapist’s support), which may affect the accuracy and reliability of the findings.

The included clinical trials12–15 were all RCTs, the hypotheses were clearly described, the method of selection from the source population and representation were described, losses to follow-up were reported, main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings were clearly described, and estimates of random variability and actual probability values were provided. Patients and assessors were not blinded to treatment assignment in three trials which may have impacted the objectivity of the outcomes assessments,12–14 while patients were blinded in one trial.15 Two trials13,14 performed calculations to determine that the trial was powered to detect a clinically important effect, and two trials did not perform such a calculation.12,15 Overall, the included studies had good internal validity. The generalizability of the findings to patients with depression or MDD who also had other comorbid mental health disorders may be limited.

Summary of Findings

Details of the findings of the included studies are provided in Appendix 4.

What is the clinical effectiveness of e-therapy for the treatment of patients with depression?

For adult patients with depression

Two SRs9,11 and two RCTs12,14 examined the efficacy of therapist-guided e-therapy in adults with depression. In general, therapist-guided e-therapy moderately reduced depressive symptoms compared to no treatment, wait list, or TAU. The combination of e-therapy and TAU lead to similar outcomes to TAU alone. Dropout rate was larger in iCBT group than in the wait list group in one trial.

The author of one SR found that therapist-guided cCBT9 (use of a computer program or mobile app that covers core methods of CBT) reduced post-treatment depressive symptoms better than no treatment, wait list, or TAU; the difference between the two groups was statistically significant, and the effect of cCBT was found to be moderate. Findings from another SR11 and one RCT(that included synchronous therapist contact)12 found that therapist-guided iCBT (use of internet-based computer programs to deliver CBT materials via text, video, audio) reduced post-treatment depressive symptoms better than wait-list. In both studies, the difference between the two groups was statistically significant, with the effect of iCBT being moderate in the SR11 and large in the RCT.12 Dropout rate was found to be larger in the iCBT group than in the wait list in the RCT.12 The authors of the SRs and RCT concluded that the implementation of therapist-guided e-therapy lead to a better reduction of depressive symptoms in adult patients than no treatment, wait list, or TAU, and that e-therapy may be an effective option for individuals unable or unwilling to access standard face-to-face CBT.

One RCT14 compared the efficacy of therapist-guided wCBT (use of weekly emails, text messages and telephone contact) combined with TAU, and TAU alone. It was not clear whether therapist contact was synchronous or asynchronous. Findings showed that changes from baseline values in depressive symptoms were not statistically significant between the two groups. The authors concluded that therapist-guided wCBT was feasible in the treatment of patients with depression.

For adult patients with major depressive disorder (MDD)

One SR10 and two RCTs13,15 examined the efficacy of therapist-guided e-therapy in adults with MDD. In general, e-therapy lead to better improvements in depression compared to no treatment, to wait list, and to TAU, and provided similar outcomes to standard face-to-face CBT. Completion rate was similar between cCBT and standard face-to-face CBT as reported in one trial.

The author of one SR10 found that therapist-guided oCBT (use of an online written materials, and/or audio/video files) reduced post-treatment depressive symptoms better than no treatment, wait list, TAU and standard face-to-face CBT together. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant, and the effect of oCBT was found to be moderate. When oCBT was compared to standard face-to-face CBT alone, the difference was not statistically significant. The authors concluded that oCBT was superior to no treatment, to wait list, and to TAU and was equivalent to standard face-to-face CBT in patients with MDD.

One RCT13 compared the efficacy of therapist-guided cCBT to standard face-to-face CBT. It was not clear whether therapist contact was synchronous or asynchronous. Findings showed that both treatment modalities lead to large and similar reduction in depressive symptoms compared to baseline. Completion rate and remission rate were also similar between the two groups. The authors concluded that therapist-guided cCBT was non-inferior to standard face-to-face CBT in the treatment of patients with MDD.

One RCT15 compared the efficacy of therapist-guided iCBT to TAU. Therapist contact was synchronous. Findings showed that the time (in weeks) that the patients were unwell was similar between the two groups. The authors concluded that therapist-guided iCBT was not superior to TAU in patients with MDD.

Limitations

Evidence on therapist-guided e-therapy for the treatment of adults with depression was based mainly on reviews of small size RCTs which may lack the power to detect clinically important effects. The accuracy of estimates from SRs was affected by the heterogeneity in the e-therapy treatments, lack of details on the components of e-therapy strategies, and undetermined amount and type of therapist support (e.g., telephone, email). Together with the lack of details on synchronicity of therapist contact in the included SRs, this is a major limitation that affects the precision of the findings conclusions. In some studies, the use of a waitlist as a comparator instead of an active treatment comparator might have led to an overestimate of the treatment effect of e-therapy. Since the included studies did not include or did not report the whether they included a military, paramilitary, or veteran population, the generalizability to this population is unclear.

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

Evidence from the included studies showed that implementation of therapist-guided e-therapy may lead to a larger reduction of depressive symptoms in adult patients with depression and MDD than no treatment, wait list, or TAU. Therapist-guided e-therapy is likely equivalent to standard face-to-face CBT for patients with MDD, and the combination of e-therapy and TAU was found to be equivalent to TAU alone in patients with depression. It is unclear whether these results generalize to a military, paramilitary, or veteran population.

The majority of studies on e-therapy for the treatment of depression examined the efficacy of the intervention in general, not separating therapist-guided from pure self-help, and were therefore not included in our review. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) has revised its 2009 guidelines and issued the 2016 guidelines for the treatment of adult patients MDD.16 The guidelines recommended “First-line psychological treatment recommendations for acute MDD include cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and behavioural activation (BA). Second-line recommendations include computer-based and telephone-delivered psychotherapy” (p 524). Despite the recommendations and the potential of e-therapy for the treatment of depression, its use seems to be lagging in clinical routine practice. Trying to explain this, one study17 found the three most important determinants for its implementation in routine care are: “(1) the acceptance of eMH (eMentalHealth) concerning expectations and preferences of patients and professionals about receiving and providing eMH in routine care, (2) the appropriateness of eMH in addressing patients’ mental health disorders, and (3) the availability, reliability, and interoperability with other existing technologies such as the electronic health records” (p 1). This is supported by findings from studies that found that patients with depression experience cCBT as predominantly positive,18 and that a decrease in score at post-treatment assessment is associated with greater odds of adhering to the intervention.19

While this review did not do an in-depth search or analysis of cost-effectiveness studies, some cost information was reported and from a healthcare provider perspective, therapist-guided e-therapy was found to be likely cost-effective for MDD relative to no treatment, wait list, TAU, and standard face-to-face CBT in the United Kingdom, Australian, and Dutch contexts.10 However, therapist-guided e-therapy are not considered cost-effective compared to wait list or TAU for depression in the Netherlands or Germany.20 With the threshold for cost-effectiveness generally based on the healthcare budget available, the generalization of these findings to a Canadian context is limited.

While it is likely that therapist-guided e-therapy interventions are effective, larger comparative RCTs with consistent reporting, and performed in a Canadian context would further confirm the potential to alleviate the mental and economic impact of depression.

References

- 1.

- 2.

Lebow

J. Overview of psychotherapies. In: Post

TW, editor. UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 26]. Available from:

www.uptodate.com Subscription required.

- 3.

- 4.

Cuijpers

P, Kleiboer

A, Karyotaki

E, Riper

H. Internet and mobile interventions for depression: Opportunities and challenges. Depress Anxiety. 2017

Jul;34(7):596–602. [

PubMed: 28471479]

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

Wells

MJ, Owen

JJ, McCray

LW, Bishop

LB, Eells

TD, Brown

GK, et al. Computer-Assisted Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Depression in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018

Mar

1;20. [

PubMed: 29570963]

- 10.

Ahern

E, Kinsella

S, Semkovska

M. Clinical efficacy and economic evaluation of online cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert rev. 2018

Feb;pharmacoecon. outcomes res.. 18(1):25–41. [

PubMed: 29145746]

- 11.

Sztein

DM, Koransky

CE, Fegan

L, Himelhoch

S. Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy delivered over the Internet for depressive symptoms: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2017

Jan

1. [

PubMed: 28696153]

- 12.

Forand

NR, Barnett

JG, Strunk

DR, Hindiyeh

MU, Feinberg

JE, Keefe

JR. Efficacy of Guided iCBT for Depression and Mediation of Change by Cognitive Skill Acquisition. Behav Ther. 2018

Mar;49(2):295–307. [

PMC free article: PMC5853137] [

PubMed: 29530267]

- 13.

Thase

ME, Wright

JH, Eells

TD, Barrett

MS, Wisniewski

SR, Balasubramani

GK, et al. Improving the Efficiency of Psychotherapy for Depression: Computer-Assisted Versus Standard CBT. Am J Psychiatry. 2018

Mar

1;175(3):242–50. [

PMC free article: PMC5848497] [

PubMed: 28969439]

- 14.

- 15.

- 16.

- 17.

- 18.

- 19.

Castro

A, Lopez-Del-Hoyo

Y, Peake

C, Mayoral

F, Botella

C, Garcia-Campayo

J, et al. Adherence predictors in an Internet-based Intervention program for depression. Cognitive Behav Ther. 2018

May;47(3):246–61. [

PubMed: 28871896]

- 20.

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

View in own window

| First author, Year, Country | Objectives

Intervention

Comparators

Literature Search

Strategy | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Number of Studies Outcomes |

|---|

| Wells,9 2018, US, Ireland | Objectives: “To examine evidence for the effectiveness of computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy (CCBT) for depression in primary care and assess the impact of therapist-supported

CCBT versus self-guided CCBT” (p e1)

Intervention (cCBT): Use of a computer program or mobile app that covers core methods of CBT to deliver the treatment (can be pure self-help or therapist-guided). Number times for therapist contact not reported.

Comparators: no treatment, wait list, TAU (no standard face to face CBT)

Literature search strategy: “A computerized literature search was conducted using Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus from their inception to July 18, 2016” (p e2) | “Criteria for inclusion of studies were (1) randomized controlled trials with control groups (ie, no treatment, wait list, attention control, or treatment as usual [TAU] other than standard face-to-face; (2) subjects were depressed as measured by depression rating scales; (3) inclusion criteria specified for depression; (4) participants were 16 years of age or older; (5) involved use of a computer program or mobile app that covers core methods of CBT to deliver all or part of the treatment;(6) pre and posttreatment mean scores with standard deviation using a standard depression rating scale; and (8) participants were drawn from a primary care settting (family medicine and internal medicine)” (p e2) | Studies not fulfilling exclusion criteria | 8 RCTs (4 on therapist-guided cCBT, 4 on pure self-help cCBT)

Efficacy:

Difference in post-treatment depressive symptoms between cCBT and comparators, determined by validated instruments (e.g., PHQ-9, BDI, CES-D)

|

| Ahern,10 2018, Ireland | Objectives: “Our systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the clinical efficacy and economic evidence for the use of online cognitive behavioral therapy (oCBT) as an accessible treatment solution for depression” (p 25)

Intervention (oCBT): use of an online written materials, and/or audio/video files, guided by a therapist. Number of therapist interactions not reported.

Comparators: no treatment, wait list, TAU, standard face to face CBT

Literature search strategy: “The electronic databases CINAHL, Cochrane, EconLit, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science were searched for studies published within the last 10 years (January 2006-December 2016)” (p 26) | “Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) adult sample with a formal diagnosis of MDD according to DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, DSM-V, ICD-9, or ICD-10 criteria, or scored above the clinical cut-off on a reliable and valid depression measure (e.g., ≥16 CES-D is comparable to a clinical diagnosis using DSM); (b) compared oCBT to treatment as usual, waitlist control, an attention control group, or traditional, face-to-face CBT as this was considered a highly relevant treatment comparator” (p 27) | “Exclusion criteria were: (a) the intervention did not primarily focus on the reduction of depressive symptoms in a MDD sample (e.g., prevention studies); (b) the oCBT intervention featured only minimal Internet delivery, that is, Internet delivery of CBT content, such as psychoeducational materials, was considered to be supplemental to face-to-face treatment, rather than the primary treatment delivery medium; (c) severe psychiatric comorbidity (e.g. schizophrenia); and (d) redundant reports” (p 27) | 29 RCTs

Efficacy:

Difference in post-treatment depressive symptoms between oCBT and comparators, determined by validated instruments (e.g., PHQ-9, BDI, CES-D)

|

| Sztein,11 2017, US | Objectives: “The objective of this meta-analysis is to assess whether Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy delivered to adults with depressive symptoms leads to a reduction in these symptoms as compared to those who receive no therapy” (p 1)

Intervention (iCBT): use of a computer program (internet-based) to deliver materials via text, video, audio (can be purely self-help or therapist-guided). Number of therapist interactions not reported.

Comparators: wait list

Literature search strategy: “Three databases were searched: Cochrane, PubMed and PsycInfo. The database searches occurred on 26 September 2015” (p 2) | “Studies were included if they were randomized controlled trials published in English between 2005-2015 conducted with adults >18 years of age experiencing mild to moderate depression where study subjects received Internet based cognitive behavioural therapy, and the control group was placed on a wait-list” (p 1) | Studies not fulfilling inclusion criteria | 14 RCTs

Efficacy:

Difference in post-treatment depressive symptoms between iCBT and comparators, determined by validated instruments (e.g., PHQ-9, BDI, CES-D) |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CBT = cognitive behaviour therapy; cCBT = computer-assisted CBT; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; iCBT = internet-assisted CBT; oCBT = online-assisted CBT; PHQ-9 = 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation; TAU = treatment as usual

Table 3Characteristics of Included Clinical Studies

View in own window

| First Author, Year, Country | Study Design Objectives | Intervention Comparators | Patients | Main Study Outcomes |

|---|

| Forand,12 2018, US | RCT. Single center.

Therapist contact was synchronous (with 3 prearranged phone calls and 1 prearranged email)

“We report results of an 8-week waitlist controlled trial of guided iCBT” (p 295) | Therapist-guided iCBT (8-week computerized, internet-delivered, CBT)

(n = 59)

Wait list (n = 30) | Adults with depression (severity and comorbidities not reported) | Efficacy: difference in posttreatment depressive symptoms between iCBT and wait list, determined by PHQ-9

Dropout rate |

| Thase,13 2018, US | RCT. Multicenter.

Non-inferiority assumption if the expected difference between the intervention and comparator is a small to moderate effect.

The method of therapist contact was not clear whether it was synchronous or asynchronous

“The authors evaluated the efficacy and durability of a therapist-supported method for computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy (CCBT) in comparison to standard cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)” (p 242) | Therapist-guided cCBT (16-week Internet-delivered CBT)

(n = 77)

Standard CBT for 16 weeks (n = 77) | Adults with MDD (severity and comorbidities not reported) | Efficacy: change from pre-treatment in depressive symptoms for cCBT and standard face-to-face CBT, determined by HAM-D score

Completion rate

Remission rate |

| Hatcher,14 2018, Canada, New Zealand | RCT. Single center.

The method of therapist contact was not clear whether it was synchronous or asynchronous

“This study aimed to test in people referred to secondary care with depression if a Web-based therapy (The Journal) supported by a coach plus usual care would be more effective in reducing depression compared with usual care plus an information leaflet about Web-based resources after 12 weeks” (p 1) | Therapist-guided wCBT (12-week web based CBT) plus usual care

(n = 35)

Usual care for 12 weeks (n = 28) | Adults with depression (severity and comorbidities not reported) | Efficacy: change from pre-treatment in depressive symptoms for wCBT + usual care, and usual care alone, determined by PHQ9 score |

| Kordy,15 2016, Germany | RCT. Multicenter.

Therapist contact was synchronous (with one-on-one chats)

“Strategies to improve the life of patients suffering from recurrent major depression have a high relevance. This study examined the efficacy of 2 Internet-delivered augmentation strategies that aim to prolong symptom-free intervals”. | Therapist-guided i-CBT (12-week internet-delivered CBT)

(n = 79)

TAU for 12 months (n = 80) | Adults with recurrent MDD (severity and comorbidities not reported) | Efficacy: number of ‘well’ and ‘unwell’ weeks, determined by the PSR of the LIFE |

CBT = cognitive behaviour therapy; cCBT = computer-assisted CBT; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; iCBT = internet-assisted CBT; LIFE = Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation; MDD = major depressive disorder; oCBT = online-assisted CBT; PHQ9 = 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PSR = Psychiatric Status Rating; RCT = randomized controlled trial; TAU = treatment as usual; wCBT = web-based CBT

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses using AMSTAR II7

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Wells9 |

|---|

a priori design provided independent studies selection and data extraction procedure in place comprehensive literature search performed list of included studies, studies characteristics provided quality assessment of included studies provided and used in formulating conclusions conflict of interest stated

|

assessment of publication bias not performed list of excluded studies not provided heterogeneity across trials in e-therapy programs (content, lengths, amount and types of therapist support)

|

| Ahern10 |

|---|

a priori design provided independent studies selection and data extraction procedure in place comprehensive literature search performed list of included studies, studies characteristics provided assessment of publication bias performed conflict of interest stated

|

list of excluded studies not provided quality assessment of included studies not provided heterogeneity across trials in e-therapy programs (content, lengths, amount and types of therapist support)

|

| Sztein11 |

|---|

a priori design provided independent studies selection and data extraction procedure in place comprehensive literature search performed list of included studies, studies characteristics provided assessment of publication bias performed conflict of interest stated

|

list of excluded studies not provided quality assessment of included studies not provided heterogeneity across trials in e-therapy programs (content, lengths, amount and types of therapist support)

|

Table 5Strengths and Limitations of Randomized Controlled Trials using Downs and Black8

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Forand12 |

|---|

randomized controlled trial hypothesis clearly described method of selection from source population and representation described loss to follow-up reported main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings clearly described estimates of random variability and actual probability values provided

|

|

| Thase13 |

|---|

randomized controlled trial hypothesis clearly described method of selection from source population and representation described loss to follow-up reported main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings clearly described power calculation to detect a clinically important effect performed estimates of random variability and actual probability values provided

|

|

| Hatcher14 |

|---|

randomized controlled trial hypothesis clearly described method of selection from source population and representation described loss to follow-up reported main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings clearly described power calculation to detect a clinically important effect performed estimates of random variability and actual probability values provided

|

assessor not blinded to patient treatment assignment more than 20% dropped out rate, leading to a sample size of completed patients that may not have an 80% power to detect a clinically important effect

|

| Kordy15 |

|---|

randomized controlled trial as sessor blinded to patient treatment assignment. hypothesis clearly described method of selection from source population and representation described loss to follow-up reported main outcomes, interventions, patient characteristics, and main findings clearly described estimates of random variability and actual probability values provided

|

|

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Author’s Conclusions

Table 6Summary of Findings of Included Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Author’s Conclusion |

|---|

| Depression |

|---|

| Wells9 (systematic review) |

|---|

Difference in posttreatment depressive symptoms between cCBT and no treatment, wait list, TAU (effect size ga)

Overall (therapist-guided and pure self-help) (data from 8 studies)

g = 0.258 (small effect); 95% CI 0.068, 0.449; P = 0.008

Therapist-guided (data from 4 studies)

g = 0.372 (moderate effect); 95% CI 0.203, 0.541; P < 0.001

Attrition rate not reported | “Implementation of therapist-supported CCBT in primary care settings could enhance treatment efficiency, reduce cost, and improve access to effective treatment for depression” (p e1) |

| Sztein11 (systematic review) |

|---|

Difference in posttreatment depressive symptoms between iCBT and wait list (SMD – mean; 95% CI)

Therapist-guided (number of studies not reported)

0.73 (moderate effect); 0.58 to 0.87; P value not reported

Attrition rate not reported | “Cognitive behavioural therapy delivered over the Internet leads to immediate and sustained reduction in depressive symptoms; thus, it may be a good treatment modality for individuals unable or unwilling to access traditional face-to-face therapy” (p 1) |

| Forand12 (clinical trial) |

|---|

Difference in posttreatment depressive symptoms between iCBT and wait list (effect size ga)

g = 1.45 (large effect); P < 0.05

Dropout rate

iCBT: 29%

wait list: 10% | “iCBT is an effective treatment for depression, but dropout rates remain high” (p 296) |

| Hatcher14 (clinical trial) |

|---|

Change from baseline in depressive symptoms wCBT + usual care and usual care alone (PHQ-9 scores - mean, SD)

wCBT + usual care: 9.4 (6.7)

Usual care: 7.1 (7.5)

Difference not statistically significant (P = 0.30)

Attrition rate not reported | “The study demonstrated that it is feasible to use a coach in this setting, that people found it helpful, and that it did not conflict with other care that participants were receiving” (p 1) |

| Major depressive disorder |

|---|

| Ahern10 (systematic review) |

|---|

Difference in posttreatment depressive symptoms between therapist-guided oCBT and no treatment, wait list, TAU, standard face-to-face CBT (effect size ga)

Compared to all comparators (data from 28 studies)

g = 0.44 (moderate effect); 95% CI 0.31 to 0.57; P < 0.00001

Compared to face-to-face CBT (data from 2 studies)

g = 0.06 (equivalent effect); 95% CI -0.67 to 0.79; P value not reported

Attrition rate not reported | “oCBT shows promise of effectively improving depressive symptoms, considering limited mental healthcare resources” (p 25) |

| Thase13 (clinical trial) |

|---|

Difference between pre-treatment and post-treatment depression (within group difference) (effect size ga)

cCBT: g = 2.4 (large effect) (P value not provided)

Standard face-to-face CBT: g = 2.0 (large effect) (P value not provided)

cCBT met a priori criteria for noninferiority to standard face-to-face CBT at week 16

No statistical difference between cCBT and CBT on any measure of psychopathology

Completion rates

cCBT: 81.8%

Standard face-to-face CBT: 79.2%

Remission rates

cCBT: 42.9%

Standard face-to-face CBT: 41.6% | “The study findings indicate that a method of CCBT that blends Internet-delivered skill-building modules with about 5 hours of therapeutic contact was non-inferior to a conventional course of CBT that provided over 8 additional hours of therapist contact” (p 242) |

| Kordy15 (clinical trial) |

|---|

Reduction of time with an unwell status by iCBT compared to TAU (OR, 95% CI)

0.62; (0.31, 1.24)

Attrition rate not reported | “Contrary to the hypothesis, SUMMIT-PERSON (therapist-guided i-CBT) was not superior to either SUMMIT (pure self-help i-CBT) or TAU” (p 91) |

- a

Effect size g = difference between groups in post treatment depression rating scale score/SD; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; CBT = cognitive-behavior therapy; cCBT = computer-assisted CBT; iCBT = internet-assisted CBT; oCBT = online-assisted CBT; OR = odds ratio; PHQ-9 = 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items score; SD = standard deviation; SMD = standardized mean difference; TAU = treatment as usual

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

e-Therapy Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Depression. Ottawa: CADTH; 2018 May. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.