Summary of Study Characteristics

Additional details regarding the characteristics of included publications are provided in Appendix 2.

Study Design

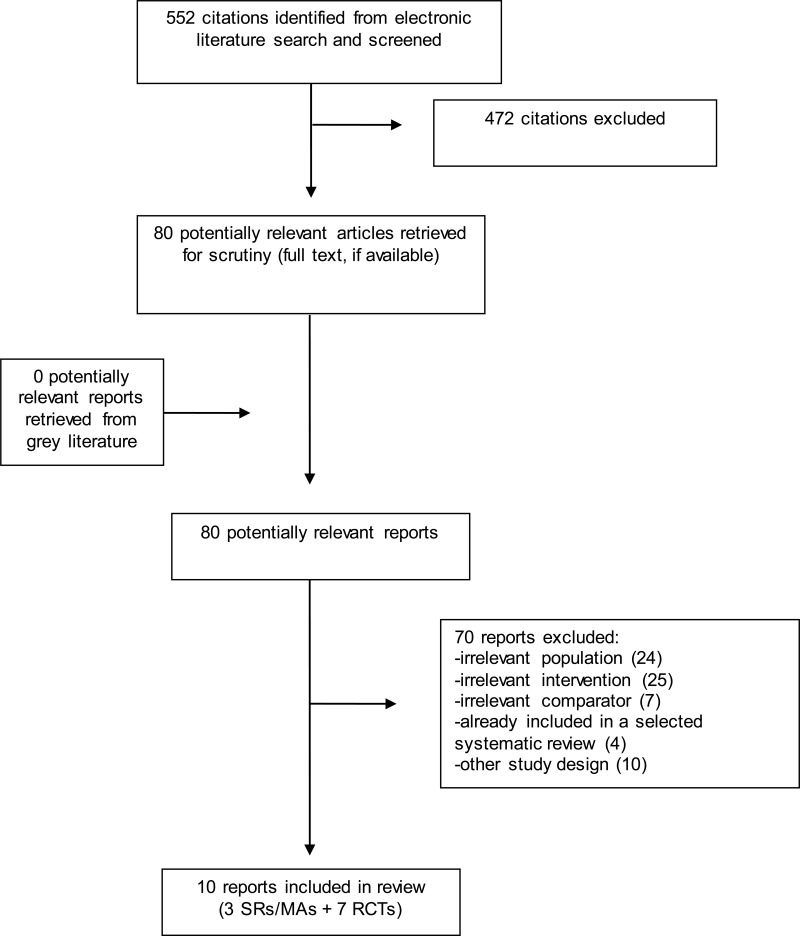

The systematic reviews/meta-analyses were published between 2015 and 2018.7–9 All reviews included RCTs and quantitative synthesis of results. Andrews et al.7 searched for RCTs until September 2016 and included 32 studies that were relevant to one of the populations of interest to this rapid review (i.e. generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or social anxiety disorder). Kampmann et al.8 searched for RCTs from 1985 to June 2015 and included 18 studies. Olthuis et al.9 searched for RCTs from 1950 to September 2014 and included 23 studies in the specific populations of interest and five studies in populations with mixed anxiety disorder (i.e. generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, or specific phobia).

The additional seven RCTs, which were not included in the included systematic reviews, were published between 2015 and 2017.10–16

Country of Origin

The countries of origin for the first authors of the systematic reviews were Australia,7 the Netherlands8, and Canada9.

The RCTs were conducted in Sweden,10,11,13,14 Switzerland, Austria, and Germany,15 Australia,16 and Romania.12

Patient Population

The review by Andrews et al.7 included adults 18 years of age or older with generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia), or social anxiety disorder as the primary diagnosis. Kampmann et al.8 included studies in adults 18 years of age or older with social anxiety disorder. Olthuis et al.9 included studies in adults over 18 years of age with generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, or mixed anxiety disorders.

The RCTs were categorized into those that focused on: (a) generalized anxiety disorder, (b) panic disorder, (c) social anxiety disorder, and (d) mixed anxiety disorders (Appendix 2).

One RCT included participants with generalized anxiety disorder.11 Dahlin et al.11 recruited adults 18 years of age or older (average: 39.5 years) with a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). In this study population, 24% also had major depression.11 Diagnostic telephone interviews were conducted with potential participants prior to randomization.

Two RCTs included participants with panic disorder.12,13 Ciuca et al.12 recruited adult participants 18 to 65 years of age (average: 35.2 years) who met diagnostic criteria for panic disorder based on the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ). Comorbid diagnoses were agoraphobia (52%), major depression (22%), generalized anxiety disorder (18%), social phobia (5%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (3%), specific phobia (2%), and bulimia (1%).12 Ivanova et al.13 recruited adults 18 years of age or older (average: 35.3 years) who met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for panic disorder. Diagnosis was conducted via telephone12,13 or Skype.12

Three RCTs included participants 18 years of age or older (average: 42.9, 35.3, and 35.4 years) with social anxiety disorder, according to the diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV.13–15 Comorbidities were common: in Johansson et al.,14 29% had depression, 25% agoraphobia, and 21% generalized anxiety disorder; and in Schulz et al.,15 about 48% had one or more comorbid disorder, such as specific phobias (16%) and current major depressive episode (15%). In all three RCTs, diagnostic telephone interviews were conducted.

Two RCTs included older participants, 60 years of age or over, with mixed anxiety disorders, as determined from a diagnostic telephone interview.10,16 Silfvernagel et al.10 recruited older adults over 60 years of age (average: 66.1 years) with recurring symptoms of anxiety. The majority (53%) of participants in this study were diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder.10 Participants were also included if they had comorbid major depression (32%), but not as the primary diagnosis.10 Other diagnoses were panic disorder (17%), panic disorder with agoraphobia (6%), social phobia (9%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (6%).10 In Dear et al.,16 participants 60 years of age or older (average: 65.4 years) with anxiety were included. Many participants (34%) fulfilled the criteria for three diagnoses, however 18% were not diagnosed with any condition. The most common diagnosis was generalized anxiety disorder (55%), followed by major depressive episode (45%), panic disorder or agoraphobia (32%), social phobia (28%), obsessive compulsive disorder (5%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (4%).16

Interventions and Comparators

Among the systematic reviews, Andrews et al.7 compared internet-supported cognitive behaviour therapy (iCBT) with care as usual, waitlist, information, or placebo. Several of the included trials incorporated therapist support with iCBT, however further details of the type of support were not provided. Kampmannn et al.8 conducted a subgroup analysis of iCBT that had a therapist-guided component, compared with either a passive control (i.e. waitlist) or an active control (i.e. CBT without internet support). Details of the guidance provided by therapists were not provided in the review. Olthuis et al.9 examined therapist-support iCBT compared with waitlist, unguided CBT, and face-to-face CBT. This review specified that a therapist-supported iCBT intervention must have been delivered over the Internet through web pages and/or email and included interaction with a therapist through email or telephone, but not face-to-face.9

In the RCT of generalized anxiety disorder,11 a therapist-guided acceptance-based iCBT program, that also included an audio compact disc and workbook, was compared with waitlist. The iCBT intervention was an online, commercially available Swedish program (“Oroshjalpen”) that consisted of seven modules and the central components of mindfulness, acceptance, and valued action. The modules were arranged in a specific order, however the user had access to the full program from the start and could navigate between modules. Participants were advised to complete one module per week in the recommended order and were given a total of nine weeks to complete the full program. Guidance was provided by four clinical psychologist graduate students, who interacted with participants through a secure messaging system, and were advised to spend a total of 15 minutes per participant per week to monitor activity, respond to messages, and provide feedback. On average, 9.3 minutes were spent on each participant per week. A licensed psychologist supervised the clinical psychologist graduate students weekly.

For panic disorder, Ciuca et al.12 compared therapist-guided iCBT with unguided iCBT and a waitlist control. The iCBT program was called PAXonline Program for Panic Disorder (PAXPD) and consisted of 16 modules that were completed over a 12-week time frame. The modules addressed education of the disorder and interventions, techniques for decreasing neurophysiological hyperarousal, exposure to feared somatic sensations, situational exposures, training in positive emotions and problem-solving, behavioural activation and cognitive restructuring exercises, and prevention of relapses. Participants had access to all modules from the start, however they were recommended to work through them in consecutive order. Guidance was provided by three licensed therapists with formal training in CBT and at least three years clinical experience, in regular weekly (or upon module completion) 15 to 45 minute video sessions (synchronous contact). During the video sessions, the therapist checked completion, understanding of module material, homework, and how the participant was feeling, answered questions, and assisted with the recommended exercises. The average total time spent by therapists per participant was 247.2 minutes, over an average of 7.8 sessions.

Ivanova et al.13 compared guided internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy (iACT) for panic disorder and social anxiety disorder, with unguided iACT and waitlist. The iACT intervention was a commercially available online Swedish program (“Angesthjalpen”) with a paper format exercise booklet and a compact disc with mindfulness and acceptance exercises. The program was transdiagnostic (i.e. relevant to both panic disorder and social anxiety disorder) and consisted of eight modules, which were completed over 10 weeks. Participants had access to all modules from the start, however they were recommended to work through them in order. Both guided and unguided intervention groups were given access to a smartphone application that included the material in the paper exercise book, and the ability to rate mood and leave comments. Guidance was provided by seven students in Masters of clinical psychology at the end of their clinical training, who provided participants with comments on treatment progress, reinforced specific desirable behaviours, provided encouragement, assisted with application of techniques to life situations and problem-solving, and ensured correct interpretations of techniques. The therapists were instructed to spend 15 minutes per participant per week and were supervised weekly by a licensed clinical psychologist.

Johansson et al.14 examined internet-based psychodynamic therapy (iPDT) for social anxiety disorder compared with waitlist. The program consisted of nine modules, which were sent to participants by therapists, one-by-one, every week over a 10-week period. The concept of the program was emotional mindfulness and participants were guided on the relationship between feelings, anxiety, and defenses. Guidance was provided by four Master level students in their final year of a five-year clinical psychologist program. The therapists kept in contact with participants through text messages that were delivered through a secure online application. Participants could contact the therapist any time during the week, although most interaction took place at the end of the week after participants sent in homework assignments. The therapists were instructed to spend 10 to 15 minutes per participant per week, and were supervised by another therapist experienced in affect-focused psychotherapy.

Schulz et al.15 compared therapist-guided group iCBT with individual iCBT and waitlist for people with social anxiety disorder. The program consisted of eight text-based modules that were completed on a weekly basis over a 12-week treatment period. The next module was made available once the participant indicated that they understood the content and agreed to complete the exercises. In the individual iCBT intervention, therapists monitored progress and contacted participants via email on a weekly basis. Participants who received individual iCBT could contact therapists through an integrated message function whenever they needed and were informed that the therapist would answer within three working days. In the group iCBT intervention, participants had access to a therapist-guided discussion forum that consisted of six members per group. All messages posted on the forum by therapists or group members were available to everyone in the group. In addition, therapists contacted the group every week to introduce the module topic and provide feedback on the group’s progress. The guidance in individual and group iCBT interventions was provided by four therapists; three were students in their last term of a graduate program in clinical psychology and psychotherapy and one had a Master degree in clinical psychology and was in the first year of a post-graduate CBT training program. The average therapist time for individual iCBT was 17 minutes per participant per week and for group iCBT 4.5 minutes per participant per week.

In the two RCTs that included participants with mixed anxiety disorders, iCBT was compared with weekly general email support from a clinician10 or waitlist.16 Silfvernagel et al.10 developed online, therapist-guided and individually tailored iCBT programs, based on the symptom profiles and needs of participants. Each participant was prescribed six to eight modules, which were completed within eight weeks. The program was transdiagnostic and incorporated education, exposure exercises, behavioural experiments, and homework assignments. Guidance by therapists was provided over a secure treatment platform, and could be initiated either by the therapist or participant. Therapists provided feedback on homework assignments within 24 hours. The average total therapist time spent per participant in the intervention was 100 minutes. The control group received weekly general email support (as a form of attention), however the clinicians who provided this support were instructed not to engage in CBT.

Dear et al.16 examined an iCBT intervention (“Managing Stress and Anxiety Course”) against a waitlist control. The iCBT program consisted of five modules, presented as text-based instructions and case studies, and delivered over an 8-week treatment period. Participants could access the modules according to a timetable. Guidance was provided in the form of brief weekly contacts by two therapists over telephone or email. The weekly contact was generally limited to five to ten minutes, although more time was provided if needed. The average total therapist time spent per participant was 57.6 minutes. The therapists were registered and experienced clinical psychologists with doctoral degrees.

Outcomes

The included studies measured outcomes based on several different scales for anxiety and depression (Appendix 2). A description of all scales is beyond the scope of this rapid review, however a brief explanation is provided for some of the commonly used scales, disorder-specific scales, and scales that were primary outcomes.

- (1)

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): An instrument that assesses 21 symptoms of anxiety on a scale of 0-3. The total score (sum of the 21 items) classifies anxiety severity: 0-21 (low anxiety), 22-35 (moderate anxiety), and ≥36 (potentially concerning levels of anxiety).17

- (2)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 – Item Scale (GAD-7): To screen for generalized anxiety disorder, a self-report measure that assesses seven items on a scale of 0-3. A total score is calculated: ≥8 (possible presence of an anxiety disorder).16

- (3)

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale – Self Rated (LSAS-SR): An instrument that assesses 24 items on a scale of 0-3, separately for fear and avoidance. A total score is calculated: no social anxiety (0-54), moderate (55-65), marked (65-80), severe (80-95), and very severe (>95).18

- (4)

Panic Disorder Severity Scale – Self Report (PDSS-SR): An instrument that assesses seven items on a five point Likert scale. A total score is calculated: a cut-off of six may indicate presence/absence of DSM-IV panic disorder and a cut-off of 14 may indicate mild/severe panic disorder.12

- (5)

Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9): An instrument that assesses nine items on a scale of 0-3 for symptoms of major depressive disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. A total score is calculated: minimal symptoms (5-9), minor/mild (10-14), moderately severe major depression (15-19), and severe major depression (>20).19

- (6)

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ): An instrument that assesses 16 items on a scale of 1-5 to measure excessive, generalized, and uncontrollable worry. A total score is calculated, with higher scores representing more severe symptoms. A score ≥45 indicates generalized anxiety disorder.20

- (7)

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS): A self-report instrument that assesses 20 items for fears in social interactions, with ratings on a five point Likert scale. A total score is calculated, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.15

- (8)

Social Phobia Scale (SPS): A self-report instrument that assesses 20 items for fears of being judged by others during daily activities. A total score is calculated, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.15

All but three7–9 of the included studies calculated the post-treatment effect sizes as Cohen’s d, which is the ratio of the mean difference (between intervention and control) and the pooled standard deviation. Andrews et al.7 and Kampmann et al.8 calculated Hedges’ g, which is similar to Cohen’s d except that the denominator is the pooled standard deviation weighted by sample size. As a rule of thumb, Hedges’ g or Cohen’s d value of 0.2 is considered a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect.8 Although the RCTs included longer term follow-up periods (from three to 24 months post-treatment), direct comparisons with the control groups could not be performed because participants in control groups were switched to the guided internet based programs after completion of the study. The follow-up periods provide within group comparative data.

Two RCTs additionally reported on diagnostic status post-treatment12,15 or clinically significant improvement.13,16 All RCTs reported a measure of attrition (e.g. number of drop-outs or number of modules completed).

Summary of Critical Appraisal

In all three systematic reviews, studies were quantitatively synthesized using random effects models.7–9 The reviews by Andrews et al.7 and Olthuis et al.9 were based on a priori protocols. The evidence base for internet-delivered therapies is prone to significant heterogeneity due to variability in interventions, trial procedures, and outcome measurement scales. Andrews et al.7 examined heterogeneity in meta-analysis according to study quality and Olthius et al.9 examined heterogeneity by study quality, anxiety disorder, and time spent by therapists. In the review by Kampmann et al.,8 however, an estimate of heterogeneity was not provided for the meta-analysis of guided iCBT. Olthuis et al.9 conducted a comprehensive search of published and unpublished literature, whereas Andrews et al.7 included only published or in press articles in English and Kampmann et al.8 did not search the grey literature. In addition, Kampmann et al.8 did not describe the type of support provided in therapist-guided iCBT.

The RCT for generalized anxiety disorder11 was properly randomized with an online random number service and the randomization was conducted by an employee of the university with no connection to the study. The waitlist control group had no contact with study administrators during the nine weeks of treatment. Guidance was provided by trained graduate students rather than licensed therapists and by the same students who conducted the initial diagnostic telephone interviews, which could have potentially affected the support provided based on knowledge of baseline scores, although there is no concrete evidence that this occurred.

The two RCTs for panic disorder were properly randomized: one with a software that balanced groups with respect to disease severity and chronicity12 and one with a random number service that stratified participants by primary diagnosis of panic disorder or social anxiety disorder.13 Both studies had an independent researcher carry out the randomization procedure and based analyses on intention-to-treat. In Ciuca et al.12 there were a large number of drop-outs (27%) and the blinding of assessors was compromised. The Ivanova et al.13 study had a small number of participants with panic disorder (n=39) and therapists in training conducted the intervention.

The RCTs on social anxiety disorder were randomized with a random number service or a computerized random number generator by independent researchers.13–15 Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted in all three studies. In two studies, therapists in training conducted the intervention.13,14 A large percentage (25%) of participants dropped out in the study by Shultz et al.15

Silfvernagel et al.10 (mixed anxiety disorders) performed randomization with an online random number service, independent of investigators. The post-treatment semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted by blinded assessors who had no earlier contact with participants. Dear et al.16 carried out permuted block randomization with a random number generator, at an independent institution. Both studies conducted intention-to-treat analysis. In Silfvernagel et al.10 there were imbalances in treatment and control groups (e.g. more participants in control group were employed: 30.3% vs. 9.1%) and there was a large percentage of losses to follow-up (33%), with a higher percentage in the treatment group compared with control. Data were assumed to be missing at random, however, this assumption may not be accurate given the larger number of drop-outs in the treatment group. The study did not provide specific details about the email support given to the control group or the therapist guidance given to the intervention group. In Dear et al.,16 an initial inclusion criterion of 8 or more on the GAD-7 was removed during the early stages of recruitment because many of the applicants did not meet this cut-off value.

Several studies mentioned potential conflicts of interest with respect to authors and their affiliations with the companies that develop or distribute the treatment programs.11–13,16

Limitations

A considerable number of RCTs have explored the use of e-therapy interventions for anxiety and this is a rapidly progressing field. The review was restricted to recent publications, available from 2015 onwards.

In all RCTs, participants self-selected into the study by responding to advertisements or notices in newspapers, television, social media, websites, in university campuses, or hospitals. These participants may have represented a motivated subset of people with anxiety disorders and they may have been more likely to engage in e-therapy interventions. It is unclear if the results are applicable to the full spectrum of people with anxiety seen in clinical practice, including individuals with lower levels of motivation.

While all RCTs implemented some form of therapist-guided e-therapy, the interventions were heterogeneous with respect to program content, length, and focus (i.e. disorder-specific vs. transdiagnostic), type of therapist-guidance (i.e. email vs. video-sessions and time spent), and qualifications and expertise level of therapists (i.e. therapists in training vs. licensed therapists). The appropriateness of combining such heterogeneous studies is unclear. Andrews et al. reported I2 statistics ranging from 35% to 84% for the various analyses.7 Although Olthuis et al.9 conducted subgroup analyses by anxiety disorder and therapist time, a comprehensive evaluation of how differences in interventions affect outcomes was not identified in the available literature. Additionally, some included studies provided few details of therapist-guidance, which made it difficult to compare with other publications.7,8,10

Blinding of participants was not possible due to the nature of the intervention. Although a few studies attempted to blind outcome assessors, the blinding could not be maintained because participants tended to disclose information about their treatments.12,15 Participant or outcome assessor knowledge of the intervention may have affected outcomes given that the measurement instruments pose subjective questions.

Several studies had large percentage of participants who were lost to follow-up (25 to 33%).10,12,15 In most studies the losses were similar among intervention and control groups, although, in one study of older adults a larger percentage was lost among participants who received iCBT. The follow-ups (from three to 24 months) were useful for assessing maintenance of treatment responses. However, the follow-up data usually could not be compared with a control group (due to provision of e-therapy to all participants upon study conclusion) and, since participants may have added other treatment modalities such as pharmacotherapy after completion of the study intervention, these results should be interpreted with caution.

No data were available for the subgroups of interest (i.e. military, para-military, and veteran populations). The RCTs were conducted primarily in European countries and Australia. The applicability of the study findings to Canadian patients with anxiety disorders and Canadian practice settings may be limited. The majority of participants in all studies were female. In few studies, the majority of participants were college or university-educated (53 to 77%).10,11