Context and Policy Issues

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the formation of a blood clot in a vein which affects adults of all ages and ethnicities.1 Clots occurring in the deep veins are called deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and those occurring in the lung and heart circulation are known as pulmonary embolisms (PE).2,3 VTE is diagnosed in one to two per 1000 persons per year, and PE is the third leading cause of overall cardiovascular death and sudden death in hospitalized patients. Approximately 10% to 30% of patients die within one month of their VTE diagnosis, and 50% have long-term complications.2 The estimated total cost for VTE and complications in Canada is at least $600 million per year.1

Virchow’s triad is a theory postulating that the pathogenesis of DVT is due to alterations in blood flow (i.e., stasis), injury to the vascular endothelium, and alterations in the blood’s constituents (i.e., acquired or inherited hypercoagulability). Risk factors for VTE are generally divided into inherited (e.g., thrombophilias, such as protein C deficiency) or acquired, and patients often have more than one risk factor.4 Acquired risk factors for DVT in hospitalized patients include prolonged immobilization in those who are critically ill, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, congestive heart failure, cancer, trauma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and surgical procedures.5

Current treatment for patients with VTE is anticoagulation, which can prevent further extension of the VTE and recurrence.3,4 Examples of drugs used for initial anticoagulation in DVT patients include unfractionated heparin, low-molecular weight heparins, oral factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban), warfarin, and fondaparinux.4 Anticoagulants may also be used in PE patients, depending on their bleeding risk and other factors.3

Historically, patients with acute DVT were restricted to bedrest to prevent dislodging a clot and causing a PE, and to enable administration of unfractionated heparin infusions.5,6 However, immobility is now considered a proposed risk factor for VTE, as it can promote stasis in blood flow, and has secondary complications such as muscle weakness and atrophy.4,5

More recent studies suggest that early ambulation and compression stockings are treatments of choice for acute VTE.6 In elderly patients with VTE (n = 991), a cohort study showed that low physical activity is one of the risk factors for mortality after a thromboembolic event.7

The current question is whether early mobilization is more beneficial for patients than bed rest following venous thromboembolism.

Research Questions

What is the clinical effectiveness of early mobilization for patients following venous thromboembolism?

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding early mobilization for patients following venous thromboembolism?

Key Findings

One systematic review concluded that early ambulation (compared with bed rest) in adequately anticoagulated patients with acute deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) did not have a higher incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE), DVT progression, or increased mortality. Although these results were statistically significant, the clinical significance is unknown. The paper also concluded that patients with initial moderate or severe pain had better pain relief with ambulation than bed rest. There was a high degree of heterogeneity in the meta-analyses of the data, indicating wide variability between the studies and thus risk of bias.

Two clinical guidelines promote early ambulation over bed rest in stable DVT patients who are anticoagulated. One guideline had a low level of evidence and a weak recommendation for ambulation over best rest, as it was based on two meta-analyses of four studies. The other guideline had a strong recommendation based on high quality evidence for physical therapy-initiated mobilization in lower-extremity DVT patients once they are therapeutically anticoagulated. This guideline identified lower quality evidence for mobilization after inferior vena cava filter placement, and provided this best practice statement based on expert opinion.

Methods

Literature Search Methods

A limited literature search was conducted on key resources including PubMed, The Cochrane Library, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, Canadian and major international health technology agencies, as well as a focused Internet search. Methodological filters were applied to exclude editorials, comments, letters and newspaper articles. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to English language documents published between January 1, 2012 and December 11, 2017.

Selection Criteria and Methods

One reviewer screened citations and selected studies. In the first level of screening, titles and abstracts were reviewed and potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. The final selection of full-text articles was based on the inclusion criteria presented in .

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they did not meet the selection criteria outlined in , they were duplicate publications, or were published prior to 2012. Additionally, guidelines were excluded if they had unclear methodology.

Critical Appraisal of Individual Studies

The included systematic review was critically appraised using the AMSTAR 2 tool8 and guidelines were assessed with the AGREE II instrument.9 Summary scores were not calculated for the included studies; rather, a review of the strengths and limitations of each included study were described narratively.

Summary of Evidence

Quantity of Research Available

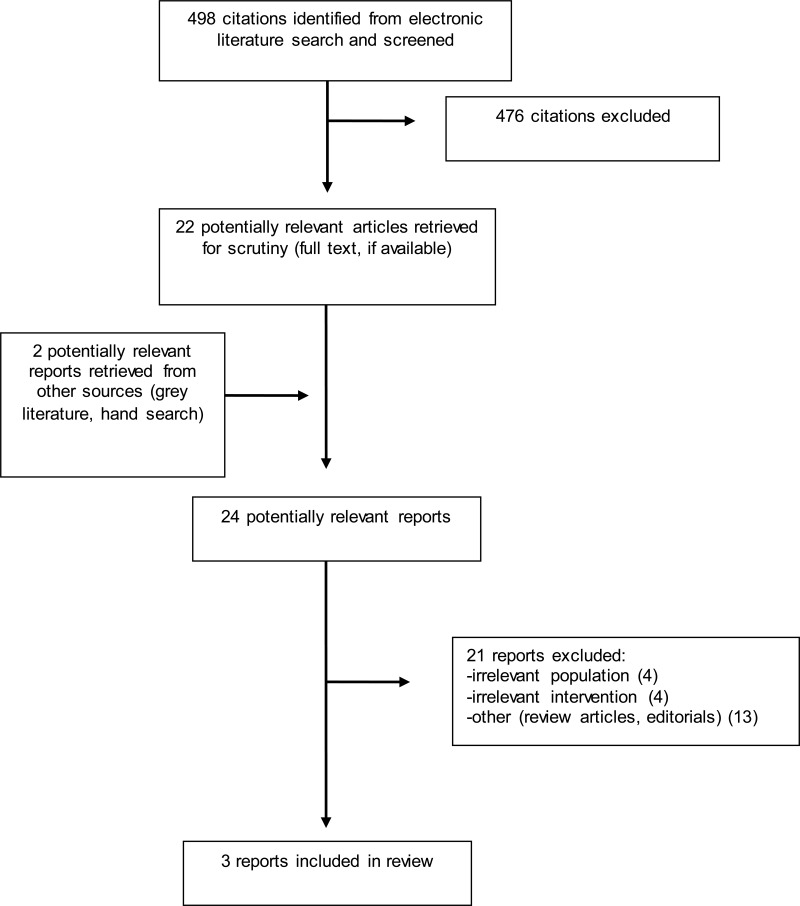

A total of 498 citations were identified in the literature search. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 476 citations were excluded and 22 potentially relevant reports from the electronic search were retrieved for full-text review. Two potentially relevant publications were retrieved from the grey literature search. Of these potentially relevant articles, 21 publications were excluded for various reasons, while three publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this report. Appendix 1 describes the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection.

There was one systematic review10 identified for the clinical effectiveness of early ambulation compared to bed rest or restricted mobility in patients with VTE. There were two-evidence based guidelines that addressed early mobilization after VTE.2,11

Additional references of potential interest are provided in Appendix 5.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Study Design

One systematic review with meta-analysis (Liu et al., 201510) met the inclusion criteria for the clinical question. The authors searched both English and Chinese language databases, including Embase, Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Sinomed, WanFangData, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective cohort studies “with good methodological design” (p. 2) published up to November, 2014. The review included 11 RCTs, one prospective study, and one retrospective cohort study.

There were two evidence-based guidelines that addressed early mobilization following VTE from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American Physical Therapy Association (APTA).

The ACCP guidelines were based on a systematic review of the literature, which identified two meta-analyses that narratively summarized evidence from four trials to support the recommendations for early mobilization. A systematic literature search was done in Medline, the Cochrane Library, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) from January 2005 (guidelines prepared in 2011). The search parameters included English-language systematic reviews, RCTs, observational studies, cohort studies, and case series. The retrieved references were screened in duplicate. The guideline recommendations were made based on expert consensus, and evaluated for supporting evidence and strength of recommendation using the ACCP-GRADE tool.11

The APTA guidelines for the role of physical therapists in the management of VTE were based on a systematic review of English-language literature, including 350 studies and 43 guidelines, from May 1, 2003 to May 2014. The literature search was performed in the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, DARE, and Physiotherapy Evidence Database, and the retrieved references were screened in duplicate. The guidelines recommendations were made based on expert consensus, and evaluated for supporting evidence and strength of recommendation using evidence-based tools.2

Country of Origin

The systematic review was published in 2015 and the investigators were from China.10 Both evidence-based guidelines were produced in the USA.2,11

Patient Population

The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the systematic review were patients with acute DVT when recruited. There were a total of 3269 patients in the included studies.10

The ACCP guidelines were directed at prescribers, and the targeted patients were those with acute DVT started on anticoagulants.11 Physical therapists were the focus of the APTA guidelines, and the target population were patients at risk for VTE and those with lower-extremity DVT.2

Interventions and Comparators

The intervention in the systematic review was early ambulation compared with initial bed rest; all patients additionally received anticoagulants. The patients in the ambulation groups (n = 1654) started treatment zero to three days after diagnosis (timing of ambulation initiation not reported in one study). The bed rest patients (n = 1595) were immobilized for three to 14 days. All patients received anticoagulation with either unfractionated heparin (or a low-molecular weight heparin) plus warfarin (or other vitamin K antagonist); one study did not include which anticoagulants were used, and the doses were not described in the review.10

The ACCP guidelines intervention was early ambulation, compared with initial bed rest.11 The intervention in the APTA guidelines was initiation of mobilization for lower-extremity DVT patients who were anticoagulated or who had an inferior vena cava filter placement.2

Outcomes

The primary endpoints for the systematic review were new pulmonary embolism (PE) and progression of the DVT. Secondary endpoints were DVT-related symptoms such as pain and edema.10

The major outcomes included in the ACCP guidelines were DVT, edema, pain, and quality of life.11 The major outcomes considered in the APTA guidelines included reduced risk of lower-extremity DVT and PE, adverse effects of bed rest, bleeding, and other anticoagulant-related adverse effects.2

A detailed summary of the characteristics of the included systematic review and evidence-based guidelines is provided in Appendix 2.

Summary of Critical Appraisal

The systematic review was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 tool8. Strengths of this review include a clearly defined research question (relevant population, intervention, comparators, and outcomes). The authors followed the PRISMA 2009 statement for transparent reporting.12 The study selection was done in duplicate, the rationale for excluding studies from the analysis was clearly outlined, and the reasons for exclusion were detailed in a separate list. The risk of bias was assessed by the systematic review authors using validated critical appraisal tools (the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool in RevMan 5.3 for RCTs, and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for non-randomized trials).10 Publication bias was assessed as per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (by funnel plot with RevMan 5.3 and Begg’s and Egger’s tests).10 Heterogeneity was calculated and the reasons for the wide variability were explored in the study limitations. The authors reported no competing interests.10

Limitations of the Liu et al. systematic review include lack of well-defined inclusion criteria for studies, which could lead to selection bias. DVT-related death was not listed as one of the primary endpoints in the eligibility criteria, but it was included in the results, which could suggest selective reporting. The authors did not indicate whether content experts were consulted to identify relevant studies for inclusion, whether they searched the grey literature or trial registries, or whether data extraction was performed in duplicate; all of these could lead to study selection bias or exclusion of pertinent studies. The summary of the included studies did not include funding sources; drug company funding can be a source of bias affecting study results. The high degree of variability or heterogeneity between the studies and their small sizes may limit the review’s applicability.10

The clinical practice guidelines were assessed using the AGREE II tool.9 The ACCP had a well-defined scope and purpose, and it had a clearly defined research questions. (relevant population, intervention, comparators, and outcomes). A systematic review of the literature was done, however, not including a grey literature or Embase search could have excluded potential studies. Retrieved references were screened in duplicate (reducing potential study selection bias). The studies and reviews were assessed for level of evidence and strength of recommendation using the ACCP-GRADE tool. Limitations of the guidelines include the lack of stakeholder feedback from patients or non-physicians, which could affect the recommendations. Tools for implementation and auditing or monitoring criteria were not included, which could affect implementation of the guidelines.11

The APTA guidelines had a clearly defined scope and purpose. A systematic review of the literature was done, and retrieved references were screened in duplicate (reducing potential study selection bias). Selected studies were assessed by three reviewers using critical appraisal tools, and systematic reviews were assessed using the AMSTAR tool. There are clear recommendations with the levels of evidence and strength of recommendation provided. The benefits, harms and costs were assessed for all recommendations, and tools for implementation were provided. Limitations of the review included lack of a grey literature or Embase search, which could have excluded potential studies. The literature search did not specify the types of studies included in the guidelines, which could lead to selection bias. Facilitators and barriers to guideline implementation were not discussed, nor were the resources required; these could affect implementation of the guideline.2

A detailed summary of the critical appraisal of the included systematic review and evidence-based guidelines is provided in Appendix 3.

Summary of Findings

What is the clinical effectiveness of early mobilization for patients following venous thromboembolism?

For the primary endpoints in patients with DVTs (new PE and progression of DVTs, DVT-related death), the meta-analysis results favored early ambulation over bed rest. Early ambulation was not associated with a higher incidence of PE or progression of the DVT than bed rest. Although the results were statistically significant, the authors did not state the clinical significance of these results, as the risk difference favoring ambulation was −0.03 [95% confidence interval: −0.05, −0.2]. There was also a high degree of heterogeneity for these results, meaning wide variability between the studies. Therefore, sensitivity analyses using a random effects model were conducted to explore sources of heterogeneity and provide a more conservative result. The conclusions of the sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary fixed effects meta-analysis.10

For relief of limb pain, the analysis favored ambulation over bed rest, but this was not statistically significant. Subgroup analysis showed a better outcome for pain relief with ambulation in patients who had moderate or severe pain initially than those with lower pain scores. There was also a high degree of heterogeneity for these results.10

Early ambulation did not provide better relief of edema in the affected limb compared to bed rest, nor did it exacerbate the edema. There was no association between the ambulatory group and DVT-related deaths, but this was not included in the primary endpoints.10

What are the evidence-based guidelines regarding early mobilization for patients following venous thromboembolism?

Both the ACCP and APTA guidelines recommend early ambulation for patients with acute DVT.2,11

The ACCP guidelines were for prescribers, and they recommend early ambulation over initial bed rest. The guidelines suggest deferring ambulation in patients with severe pain and edema, and using compression stockings in these patients. The authors described this as a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence, as it was based on 2 meta-analyses from four studies, and therefore there is a high risk of bias and imprecision.11

The APTA guidelines are directed towards physiotherapists. For patients with a lower extremity DVT and who are at therapeutic levels for anticoagulants, the guidelines recommend that physiotherapists should initiate mobilization of the patient. The authors assessed this as a strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence. The guidelines also recommend mobilization in lower extremity DVT patients after inferior vena cava filter placement. The latter was described as a best practice point based on expert opinion, and therefore a lower grade of evidence.2

A detailed summary of the systematic review findings and recommendations of the evidence-based guidelines is provided in Appendix 4.

Limitations

The authors of the systematic review stated that limitations of the analysis included the small numbers and sample sizes of the studies, and differences between studies in ambulation protocols, timing of ambulation, duration of bed rest, and follow-up periods. The studies also excluded PE patients, and there could be false negative results for symptomatic PE. There was also significant heterogeneity amongst the studies.10 As well, the results of this meta-analysis can only be applied to patients with DVT and not those with a PE.

The recommendation relevant to this report from the ACCP guidelines was weak and based on low quality evidence. The evidence was determined to be of low quality because of the risk of bias and imprecision in the meta-analyses supporting this recommendation, which were based on four studies.11 The APTA guidelines are for patients with lower-extremity DVT only. The recommendation for mobilization after inferior vena cava filter placement is based on expert opinion, and therefore may not apply to all patients.2

Conclusions and Implications for Decision or Policy Making

The literature and guidelines identified for this report suggest that early mobilization for lower extremity DVT does not increase the risk of PE in patients compared to bed rest, nor does it lead to DVT progression. The systematic review’s results provide statistical significance for these outcomes, but the clinical significance is unknown.10 The ACCP guideline recommendations for early mobilization are also based on small numbers of studies and therefore subject to bias.11 Mobilization may be beneficial in reducing pain and edema from DVTs, but larger scale studies or patient numbers are required to validate these outcomes. Further research is also required to determine if early mobilization is better than bed rest for patients with a PE.

References

- 1.

- 2.

Hillegass

E, Puthoff

M, Frese

EM, Thigpen

M, Sobush

DC, Auten

B, et al

Role of physical therapists in the management of individuals at risk for or diagnosed with venous thromboembolism: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Phys Ther. 2016

Feb;96(2):143–66. [

PubMed: 26515263]

- 3.

Tapson

VF. Treatment, prognosis, and follow-up of acute pulmonary embolism in adults. In: Post

TW, editor. [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017

Apr

6 [cited 2018 Jan 15]. Available from:

www.uptodate.com Subscription required.

- 4.

Bauer

KA, Lip

GYH. Overview of the causes of venous thrombosis. In: Post

TW, editor. [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2017

Aug

22 [cited 2018 Jan 12]. Available from:

www.uptodate.com Subscription required.

- 5.

- 6.

Ando

G, Trio

O, Manganaro

R, Manganaro

A. To promote endothelial function: The elusive link between physical therapy of venous thromboembolism and improved outcomes?

Int J Cardiol. 2016

Jul

1;214:31–2. [

PubMed: 27057968]

- 7.

Faller

N, Limacher

A, Mean

M, Righini

M, Aschwanden

M, Beer

JH, et al

Predictors and causes of long-term mortality in elderly patients with acute venous thromboembolism: a prospective cohort study. Am J Med. 2017

Feb;130(2):198–206. [

PubMed: 27742261]

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

Kearon

C, Akl

EA, Comerota

AJ, Prandoni

P, Bounameaux

H, Goldhaber

SZ, et al

Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012

Feb;141(2 Suppl):e419S–e496S. [

PMC free article: PMC3278049] [

PubMed: 22315268]

- 12.

Liberati

A, Altman

DG, Tetzlaff

J, Mulrow

C, Gotzsche

PC, Ioannidis

JP, et al

The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. [

PubMed: 19631507]

- 13.

Appendix 1. Selection of Included Studies

Appendix 2. Characteristics of Included Publications

Table 2Characteristics of Included Systematic Review

View in own window

| First Author, Publication Year, Country | Table 2: Characteristics of Included Systematic Review | Table 2: Characteristics of Included Systematic Review | Table 2: Characteristics of Included Systematic Review | Table 2: Characteristics of Included Systematic Review |

|---|

| Liu et al., 2015, China10 | Included 11 RCTs, 1 prospective study, and 1 retrospective cohort study.

Studies were from China (n = 3); Spain (n = 3); Germany (n = 2); Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Turkey, and Sweden (n = 1 each) | Acute phase of DVT | Intervention:

Early ambulation + anticoagulation (n = 1674) Ambulation started on day 0 to 2 (not reported in 1 study).

Comparator:

Bed rest + anticoagulation (n = 1595

Duration of bed rest was from 3 to 14 days. | Primary endpoints: New PE, DVT progression, DVT-related death

Secondary endpoints: DVT-related parameters (pain, edema) |

DVT = deep vein thrombosis; n = number; PE = pulmonary embolism; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Table 3Characteristics of Included Guidelines

View in own window

| Objectives | Methodology |

|---|

| Target Population/Intended Users | Intervention and Practice Considered | Major Outcomes Considered | Evidence Collection, Selection, and Synthesis | Evidence Quality Assessment | Recommendations Development and Evaluation | Guideline Validation |

|---|

| Kearon et al., ACCP 201211,13 |

|---|

Target population: Patients with acute DVT started on anticoagulants

Intended users: Prescribers | Early ambulation, initial bed rest | DVT, edema, pain, quality of life | SR: Electronic databases (Medline, Cochrane Library, and DARE) searched for SRs, RCTs, observational studies, cohort studies, and case series, from January 2005 (end date not available, but guidelines prepared Oct 2011).

Retrieved references screened in duplicate, evidence summarized narratively. | All original studies assessed for bias.

ACCP-GRADE tool used to assess the evidence.

Levels of evidence:

Grade A: High

Grade B: Moderate

Grade C: Low | Expert consensus based on review of evidence. Strength of recommendation assigned according to GRADE criteria.

Recommendation strength:

Grade 1: Strong

Grade 2: Weak | Internal and external peer review |

| Hillegass et al., APTA 20162 |

|---|

Target population: Patients at risk for VTE and those with LE-DVT

Intended users: Physical therapists | Mobilization for LE-DVT patients when anticoagulated and after IVC filter placement. | Reduced risk of LE-DVT and PE, adverse effects of bed rest, bleeding and other risks with anticoagulants | SR: Electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, WoS, Cochrane Database of SR, DARE, and PEDro) searched for literature on mobilization and anticoagulant therapy to prevent and treat VTE. Literature published from May 1, 2003 to May, 2014. CPGs searched using same MeSH parameters in NGC and TRIP database, from 2003 to 2014.

Retrieved references screened in duplicate, evidence summarized in tables and narratively. | Included literature assessed by EBM tools (used by 3 reviewers to assess 350 literature articles).

The AGREE-II tool was used to assess the clinical practice guidelines.

Systematic reviews were assessed using the AMSTAR tool.

Levels of evidence:

I: High quality studies (e.g., RCTs, cohort studies)

II: Lesser quality studies (e.g., prospective studies)

III: Case-controlled or retrospective studies

IV: Case studies and series

V: Expert opinion | Expert consensus based on review of the evidence.

Grades for recommendations:

A: Strong

B: Moderate

C: Weak

D: Theoretical/foundational

P: Best practice

R: Research | Self-assessed using the AGREE-II tool.

Internal and external peer review |

ACCP = American College of Chest Physicians; AMSTAR = A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews; APTA = American Physical Therapy Association; CPG = clinical practice guidelines; DARE = Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; EBM = evidence-based medicine; IVC = inferior vena cava; LE-DVT = lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis, PEDro = Physiotherapy Evidence Database); RCT = randomized controlled trial; SR = systematic review; VTE = venous thromboembolism, WoS = Web of Science.

Appendix 3. Critical Appraisal of Included Publications

Table 4Strengths and Limitations of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses using AMSTAR 28

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Liu et al., 201510 |

|---|

PICO format followed. Followed PRISMA 2009 statement for transparent reporting. Authors searched both English and Chinese language databases, including Embase, Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Sinomed, WanFangData, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, with literature up to November, 2014. Study selection done in duplicate. References for review articles reviewed for further articles. Rationale for study exclusion was outlined. Risk of bias assessed for the RCTs using Cochrane Risk of Bias scale and Newcastle-Ottawa scale for non-randomized trials. Authors considered the risk of bias on the study results. Publication bias assessed by funnel plot with RevMan 5.3 and Begg’s and Egger’s tests. A quality assessment was performed on the cohort study, case-controlled study, and non-randomized trial. Authors consulted the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and considered the risk of bias in the results. The authors included possible reasons for heterogeneity of the analysis, and the effects on the results. Sensitivity analyses using a random effects model were performed to assess the impact of heterogeneity on results. Authors reported no competing interests.

| No explanation for inclusion of only randomized controlled trials and cohort studies. Exclusion of other studies could lead to bias. DVT-related death was not listed as one of the primary endpoints in the eligibility criteria, but it was included in the results. Did not indicate whether content experts consulted, which could affect the studies included in the review. Did not indicate whether grey literature or trial registries searched, which could affect the results. Unknown whether authors performed data extraction in duplicate, which could lead to bias in study selection. Lacking details on individual studies for drug doses, study locations. Lack of details on individual study funding sources could lead to bias. Varying results regarding publication bias. Authors suspected other sources of asymmetry (e.g. poor methodological quality) as reason for false publication bias The risk of bias with individual studies not discussed in the evidence synthesis or results. Analysis results reported statistical significance, but not clinical significance. High degree of heterogeneity (I2 more than 75%) for studies used in data pooling for primary endpoints (DVT extension, PE, and death) and edema.

|

DVT = deep vein thrombosis; PICO = population, intervention, comparator, outcome; RCT = randomized controlled trials.

Table 5Strengths and Limitations of Guidelines using AGREE II9

View in own window

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|

| Kearon et al., ACCP 201211 |

|---|

The scope and purpose of the guidelines were well defined. PICO format was used for the clinical questions. Literature searched was done in Medline, Cochrane Library, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects. Economic implications of therapies considered. Evaluated individual RCTs, observational studies, and cohort studies, and case series for risk of bias. Evidence assessed using the ACCP version of the GRADE tool. There was a clear and explicit link between evidence and recommendations.

| No stakeholder feedback from patients or non-physicians, which could affect recommendations. Advice and tools for implementation not included. Auditing or monitoring criteria not included. Literature search did not include Embase or grey literature, which could potentially affect results.

|

| Hillegass et al., APTA 20162 |

|---|

The scope and purpose of the guidelines were well defined. Literature search was done in PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database. The authors reviewed 350 studies and 43 guidelines. There was stakeholder review from physiotherapists, physicians, nurses, and patients. The search, criteria for inclusion, and tools to assess the literature were well defined. Systematic reviews were assessed using the AMSTAR tool, and the selected articles were assessed by 3 people using 1 of 3 evidence-based critical appraisal tools. There was a clear and explicit link between evidence and recommendations. The guideline was self-assessed using the AGREE II tool to assess the methodological quality The benefits, harms and costs were assessed for each recommendation. Tools for implementation were provided.

| Literature search did not specify types of studies included in the guidelines (e.g., RCTs). Facilitators and barriers to guideline implementation were not discussed. Resources required for guideline implementation were not considered. Literature search did not include Embase or grey literature.

|

ACCP = American College of Chest Physicians; AGREE II = Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; APTA = American Physical Therapy Association; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; PICO = population, interv ention, comparator, outcome.

Appendix 4. Main Study Findings and Author’s Conclusions

Table 6Summary of Findings of Included Studies

View in own window

| Main Study Findings | Author’s Conclusion |

|---|

| Liu et al., 201510 |

|---|

| Meta-analysis of primary endpoints: New PE, DVT Progression, DVT-related death (13 studies) | “Compared to conventional bed rest treatment, early ambulation was not associated with a higher incidence of PE, progression of DVT or DVT related death in acute DVT patients with effective anticoagulation regimen.” p.12–13

“Using a fixed effect model, heterogeneity test (Chi2 = 24.71, df = 6, p = 0.0004; I2 = 76%) showed significant variance among the studies. […] Subgroup analysis found that if the patients suffered moderate or severe pain initially, early ambulation was related to a better outcome than bed rest group, in term of reduction of acute pain in the affected limb (SMD 0.42, 95%CI 0.09~0.74; Z = 2.52, p = 0.01; random effect model, Tau2 = 0.04).[…]” p. 6–7, 9

“In terms of edema in acute DVT patients, we found that early ambulation was not associated with a better remission of edema of the affected limb. Several studies […] reported a positive effect while others [..] did not. However, it should be noticed that no exacerbation of edema was ever reported with early ambulation.” p. 11 |

| Early ambulation | Bed Rest | Weight | Risk Difference (95% CI), Fixed |

|---|

| Total events/total patients | 65/1674 | 89/1595 | 100% | −0.03 [−0.05, −0.02] |

| Heterogeneity | Chi2 = 148.16, df = 12 (P < 0.00001); I2 = 92% |

| Overall effect | Z = 4.79 (P < 0.00001) |

| Meta-analysis of secondary endpoint: Limb pain, measured by VAS change (7 studies) |

| Early ambulation | Bed Rest | Weight | Std Mean Difference (95% CI), Fixed |

|---|

| Total events | 234 | 205 | 100% | 0.08 [-0.11, 0.27] |

| Heterogeneity | Chi2 = 24.71, df = 6 (P < 0.0004); I2 = 76% |

| Overall effect | Z = 0.84 (P = 0.4) |

| Subgroup analysis of VAS change during the treatment period |

| Early ambulation | Bed Rest | Weight | Std Mean Difference (95% CI), Random |

|---|

| Initial mean VAS more than 4 or 40 (5 studies) |

|

| Subtotal | 135 | 115 | 67.6% | 0.42 [0.09, 0.74] |

| Heterogeneity | Tau2 = 0.04; Chi2 = 5.82, df = 4 (P = 0.21); I2 = 31% |

| Overall effect | Z = 2.52 (P = 0.01) |

| Initial mean VAS less than 4 or 40 (2 studies) |

| Subtotal | 99 | 90 | 32.4% | -0.15 [-1.03, 0.73] |

| Heterogeneity | Tau2 = 0.35; Chi2 = 8.07, df = 1 (P =0.004); I2 = 88% |

| Overall effect | Z = 0.32 (P = 0.75) |

| Total events | 234 | 205 | 100% | 0.26 [-0.15, 0.67] |

| Heterogeneity | Tau2 = 0.22; Chi2 = 24.71, df = 6 (P = 0.0004); I2 = 76% |

| Test for subgroup differences | Chi2 = 1.37, df = 1 (P= 0.24); I2 =27.2% |

| Meta-analysis of secondary endpoint: Edema, measured by change of circumference of affected limb |

| Early ambulation | Bed Rest | Weight | Std Mean Difference (95% CI), Fixed |

|---|

| Total events | 182 | 156 | 100% | 0.27 [0.05, 0.49] |

| Heterogeneity | Chi2 = 34.7, df = 5 (P < 0.00001); I2 = 86% |

| Overall effect | Z = 2.36 (P = 0.02) |

CI = confidence interval; std = standard; VAS = visual analogue scale.

Table 7Summary of Recommendations in Included Guidelines

View in own window

| Recommendations | Grade/Strength of Recommendation and Evidence |

|---|

| Kearon et al., ACCP 201211 |

|---|

| Recommendation 2.14: Recommend early ambulation over initial bedrest. Ambulation should be deferred if edema and pain are severe. | Level of evidence: C (Low)

Strength of recommendation: 2 (Weak) |

| Hillegass et al., APTA 20162 |

|---|

Recommendation 8: Mobilize LE-DVT patients once therapeutic levels of anticoagulation have been reached

Recommendation 10: Recommend mobilizing patients after IVC filter placement once hemodynamically stable | Level of evidence: I (High-quality),

Strength of recommendation: A (Strong)

Level of evidence: V (Expert opinion).

Strength of recommendation: P (Best practice) |

ACCP = American College of Chest Phy sicians; APTA = American Phy sical Therapy Association; IVC = inferior vena cava; LE-DVT = lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis.

Appendix 5. Additional References of Potential Interest

Retrospective study – no bed rest comparison

Noack

F, Schmidt

B, Amoury

M, Stoevesandt

D, Gielen

S, Plfaumbaum

B, et al

Feasability and safety of rehabilitation after venous thromboembolism. Vasc Health Risk Manag

2015;11:397–401 [

PMC free article: PMC4508081] [

PubMed: 26203256]

Review articles

Izcovich

A, Popoff

F, Rada

G. Early mobilization versus bed rest for deep vein thrombosis. Medwave

2016;16

Suppl 2:e6478 [

PubMed: 27391009]

Pillai

AR, Raval

JS. Does early ambulation increase the risk of pulmonary embolism in deep vein thrombosis?

Home Healthc Nurse

2014;32(6):336–42 [

PubMed: 24887269]

Clinical practice guidelines – unclear methodology

About the Series

CADTH Rapid Response Report: Summary with Critical Appraisal

Funding: CADTH receives funding from Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial governments, with the exception of Quebec.

Suggested citation:

Early mobilization for patients with venous thromboembolism: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa: CADTH; 2018 Jan. (CADTH rapid response report: summary with critical appraisal).

Disclaimer: The information in this document is intended to help Canadian health care decision-makers, health care professionals, health systems leaders, and policy-makers make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. While patients and others may access this document, the document is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose. The information in this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or as a substitute for the application of clinical judgment in respect of the care of a particular patient or other professional judgment in any decision-making process. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not endorse any information, drugs, therapies, treatments, products, processes, or services.

While care has been taken to ensure that the information prepared by CADTH in this document is accurate, complete, and up-to-date as at the applicable date the material was first published by CADTH, CADTH does not make any guarantees to that effect. CADTH does not guarantee and is not responsible for the quality, currency, propriety, accuracy, or reasonableness of any statements, information, or conclusions contained in any third-party materials used in preparing this document. The views and opinions of third parties published in this document do not necessarily state or reflect those of CADTH.

CADTH is not responsible for any errors, omissions, injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use (or misuse) of any information, statements, or conclusions contained in or implied by the contents of this document or any of the source materials.

This document may contain links to third-party websites. CADTH does not have control over the content of such sites. Use of third-party sites is governed by the third-party website owners’ own terms and conditions set out for such sites. CADTH does not make any guarantee with respect to any information contained on such third-party sites and CADTH is not responsible for any injury, loss, or damage suffered as a result of using such third-party sites. CADTH has no responsibility for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by third-party sites.

Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein are those of CADTH and do not necessarily represent the views of Canada’s federal, provincial, or territorial governments or any third party supplier of information.

This document is prepared and intended for use in the context of the Canadian health care system. The use of this document outside of Canada is done so at the user’s own risk.

This disclaimer and any questions or matters of any nature arising from or relating to the content or use (or misuse) of this document will be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and the laws of Canada applicable therein, and all proceedings shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Province of Ontario, Canada.