Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-.

CASRN: 54-85-3

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Because of the low levels of isoniazid in breastmilk and safe administration directly to infants, it is unlikely to cause adverse reactions in infants, but infants should be monitored for rare instances of jaundice. Giving the maternal once-daily dose before the infant's longest sleep period will decrease the dose the infant receives. The amount of isoniazid in milk is insufficient to treat tuberculosis in the breastfed infant. If breastfed infants are treated with isoniazid, they should also receive pyridoxine 1 mg/kg daily.[1] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other professional organizations state that breastfeeding should not be discouraged in women taking isoniazid.[2]

All nursing mothers who are taking isoniazid should take 25 mg of oral pyridoxine daily.[2] A study of nursing African mothers with concurrent HIV and tuberculosis infections found that those receiving isoniazid had an increased risk of niacin deficiency (pellagra). The authors suggested that a multivitamin supplement might be advisable during isoniazid therapy in populations with undernutrition.[3]

Drug Levels

Maternal Levels. Thirty mothers (time postpartum not stated) were given a single oral dose of 200 mg of isoniazid and a single milk sample was taken from each mother at various times between 2 and 7 hours after the dose. An average peak milk level of 2.1 mg/L (range 1.7 to 2.3 mg/L) occurred in 6 women at 2 hours after the dose. By 7 hours after the dose the average milk level was 0.46 mg/L (range 0.3 to 0.6 mg/L) in 3 women.[4]

Three mothers were given single oral isoniazid doses of 300 mg (5 mg/kg) and 600 mg (10 mg/kg). Peak isoniazid levels occurred 3 hours after the dose in all cases. Peak levels were 5.4 to 5.5 mg/L after 300 mg and 9 to 10.6 mg/L after 600 mg. At 12 hours after the dose, milk levels were undetectable (<0.25 mg/L) after the 300 mg dose and 0.25 to 0.5 mg/L after the 600 mg dose.[5]

A lactating mother (time postpartum not stated) was given a single oral 300 mg dose of isoniazid after weaning. Breastmilk was collected at various times during the next 24 hours. Peak milk levels of 16.6 mg/L of isoniazid occurred at 3 hours and 3.8 mg/L of acetylisoniazid occurred at 5 hours after the dose. Both were still detectable in milk at 24 hours. Half-lives in milk were 5.9 hours for isoniazid and 13.5 hours for acetylisoniazid. The authors estimated that a total of 7 mg would be excreted into milk in 24 hours.[6]

Seven women with an average weight of 40 kg had been receiving isoniazid 300 mg once daily for at least 34 days. All women were also receiving rifampin and ethambutol. Blood and milk samples were collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours after a dose for analysis of isoniazid; metabolites were not measured. Peak milk isoniazid concentrations of 2 to 6.7 mg/L occurred 1 hour after the dose and dropped by about half by 4 hours after the dose. The authors calculated that a fully breastfed infant would receive a dose of 89.9 mcg/kg daily compared to a recommended infant dosage of 10 mg/kg daily. This dose is equivalent to 1.2% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.[7]

A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model was developed for isoniazid. The model showed that mothers given 300 mg daily who were fast metabolizers of INH would have a breastmilk level of 5.2 mg/L and slow metabolizers would have breastmilk levels of 6.75 mg/L. These amounts would provide a dose of 0.58 mg daily to their infants if they were fast metabolizers and a dose of 1.49 mg daily to their infants if they were slow metabolizers. The model predicted that the weight-adjusted infant dosage would be 0.2% of maternal dosage in the milk of fast-metabolizer mothers and 0.5% of maternal dosage in the milk of slow-metabolizer mothers.[8]

Two breastfeeding women with tuberculosis were receiving ethambutol as well as at least 4 other antituberculars donated 1 mL breastmilk samples by manual expression at approximately 6 weeks postpartum. Samples were obtained immediately prior to a dose and 2, 4, and 6 hours after a dose of 900 mg of isoniazid. Peak milk isoniazid concentrations of 14 and 17.6 mg/L occurred at about 2 to 4 hours after a dose. The authors used the peak concentrations to calculate infant daily dosages of 2.1 and 2.64 mg/kg, which ranged from 14 to 26% of the infant dosage and 12.1 to 16.4% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage. These values are overestimates because peak milk concentrations were used rather than average concentrations. In addition, acetylisoniazid was measured in peak milk concentrations of 4 to 8 mg/L.[9]

Infant Levels. Isoniazid was detectable in the urine of 2 of 3 breastfed infants whose mothers were given a single oral dose of 600 mg. The total amount excreted by the infants over 24 hours was about 6.8 to 7 mg.[5] Metabolites were not measured.

A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model was developed for isoniazid. The model showed that mothers given 300 mg daily would result in infant plasma levels of 0.07 mg/L if both mother and infant were fast metabolizers. If both were slow metabolizers, infant levels would be 0.25 mg/L. Infant serum levels would be intermediate if mothers and infants had opposite metabolizer status.[8]

Effects in Breastfed Infants

In one uncontrolled study, 6-beta-hydroxycortisol levels were measured in 10 male infants whose mothers had tuberculosis and took ethambutol 1 gram daily plus isoniazid 300 mg daily and the infants of mothers (apparently without tuberculosis) who took no chronic drug therapy. The infants of mothers taking the antituberculars had consistently lower 6-beta-hydroxycortisol levels on 8 occasions at 15-day intervals from 90 to 195 days of age, but these differences were statistically significant on days 120 and 195 only. The authors attributed the lower levels to inhibition of hepatic metabolism of cortisol to 6-beta-hydroxycortisol by the antitubercular drugs in milk.[10] However, ethambutol is not known to inhibit drug metabolism, so if the effect occurs it is more likely caused by isoniazid.

One woman taking rifampin 450 mg, isoniazid 300 mg and ethambutol 1200 mg daily during pregnancy and rifampin 450 mg and isoniazid 300 mg for the first 7 months of lactation (extent not stated). The infant was born with mildly elevated serum liver enzymes which persisted for to 1 (alanine transferase) to 2 years (aspartate transaminase), but had no other adverse reactions.[11]

Isoniazid was used as part of multi-drug regimens to treat 2 pregnant women with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and postpartum. Their two infants were breastfed (extent and duration not stated). At age 3.9 and 4.6 years, the children were developing normally except for a mild speech delay in one.[12]

Two mothers in Turkey were diagnosed with tuberculosis at the 30th and 34th weeks of pregnancy. They immediately started isoniazid 300 mg, rifampin 600 mg, pyridoxine 50 mg daily for 6 months, plus pyrazinamide 25 mg/kg and ethambutol 25 mg/kg daily for 2 months. Both mothers breastfed their infants (extent not stated). Their infants were given isoniazid 5 mg/kg daily for 3 months prophylactically. Tuberculin skin tests were negative after 3 months and neither infant had tuberculosis at 1 year of age. No adverse effects of the drugs were mentioned.[13]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

Relevant published information was not found as of the revision date.

References

- 1.

- Di Comite A, Esposito S, Villani A, et al. How to manage neonatal tuberculosis. J Perinatol. 2016;36:80–5. [PubMed: 26270256]

- 2.

- Nahid P, Dorman SE, Alipanah N, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e147–e195. [PMC free article: PMC6590850] [PubMed: 27516382]

- 3.

- Nabity SA, Mponda K, Gutreuter S, et al. Isoniazid-associated pellagra during mass scale-up of tuberculosis preventive therapy: A case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:e705–e714. [PubMed: 35427527]

- 4.

- Lass A, Bünger P. Klin Wochenschr. 1953;31:606–8. [Studies on the diffusion of isoniazid in the fetal circulation, the amniotic fluid and human milk] [PubMed: 13097858]

- 5.

- Ricci G, Copaitich T. Modalità di eliminazione dell'isoniazide somministrata per via orale attraverso il latte di donna. Rass Clin Ter. 1954;53:209–14. [PubMed: 14372127]

- 6.

- Berlin CM Jr, Lee C. Isoniazid and acetylisoniazid disposition in human milk, saliva and plasma. Fed Proc. 1979;38(part 1):426. [Abstract]

- 7.

- Singh N, Golani A, Patel Z, et al. Transfer of isoniazid from circulation to breast milk in lactating women on chronic therapy for tuberculosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:418–22. [PMC free article: PMC2291261] [PubMed: 18093257]

- 8.

- Garessus EDG, Mielke H, Gundert-Remy U. Exposure of infants to isoniazid via breast milk after maternal drug intake of recommended doses is clinically insignificant irrespective of metaboliser status. A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling approach to estimate drug exposure of infants via breast-feeding. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:5. [PMC free article: PMC6349757] [PubMed: 30723406]

- 9.

- Zuma P, Joubert A, van der Merwe M, et al. Validation and application of a quantitative LC-MS/MS assay for the analysis of first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, rifabutin and their metabolites in human breast milk. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2022;1211:123489. [PMC free article: PMC9652742] [PubMed: 36215877]

- 10.

- Toddywalla VS, Patel SB, Betrabet SS, et al. Can chronic maternal drug therapy alter the nursing infant's hepatic drug metabolizing enzyme pattern? J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35:1025–9. [PubMed: 8568011]

- 11.

- Peters C, Nienhaus A. Fallbericht einer beruflich erworbenen tuberkulose in der schwangerschaft. Pneumologie. 2008;62:695–8. [PubMed: 18855309]

- 12.

- Drobac PC, del Castillo H, Sweetland A, et al. Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis during pregnancy: Long-term follow-up of 6 children with intrauterine exposure to second-line agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1689–92. [PubMed: 15889370]

- 13.

- Keskin N, Yilmaz S. Pregnancy and tuberculosis: To assess tuberculosis cases in pregnancy in a developing region retrospectively and two case reports. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:451–5. [PubMed: 18273625]

Substance Identification

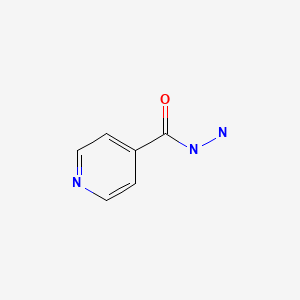

Substance Name

Isoniazid

CAS Registry Number

54-85-3

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

- User and Medical Advice Disclaimer

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Record Format

- LactMed - Database Creation and Peer Review Process

- Fact Sheet. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed)

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Glossary

- LactMed Selected References

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - About Dietary Supplements

- Breastfeeding Links

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Isoniazid - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)Isoniazid - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)

- MIR544A microRNA 544a [Homo sapiens]MIR544A microRNA 544a [Homo sapiens]Gene ID:664613Gene

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...