In the second keynote presentation Peter Orszag, vice chairman at CitiGroup, Inc., and a columnist for Bloomberg View, addressed the fiscal impacts on education of the dramatic rise in health care expenditures and suggested some possibilities for better structuring the nation’s investments in both areas. He began by citing a variety of indicators demonstrating the dismal state of funding for public higher education. Thirty-five years ago, he said, a starting assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign earned about the same amount as a starting assistant professor at the University of Chicago. The same comparison held true for the University of Texas at Austin and Rice University. By the year 2000, however, new assistant professors at Illinois and Texas were earning 15 percent less than their counterparts at Chicago and Rice, and by this year that differential had widened to 20 percent (see Figure 4-1). The impact of this disparity is significant, as evidenced by the imperfect but nonetheless useful U.S. News & World Report rankings of U.S. colleges and universities. In 1987 there were 8 public universities in the top 25, while in 2014 there were only 3, with the highest of the 3—the University of California, Berkeley—ranking number 20; it had been ranked fifth in 1987. Other metrics paint the same picture, Orszag said.

FIGURE 4-1

Percentage change in the average salary for senior higher education administrators and full-time faculty members by sector, 1978–1979 to 2013–2014. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing Curtis and Thornton, 2014.

While it is not obvious at first, this pattern is another manifestation of the complicated relationship between health and education. According to research that Orszag has conducted with Thomas Kane of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a major factor in the relative decline in the quality of public universities has been the falling ratio of spending per student at public universities relative to private universities. That drop in turn has been driven in large part by shifts in state government appropriations, which themselves have been driven by Medicaid and other health expenditures. One-quarter of a century ago, state government support for higher education was 50 percent greater than state government spending on health care. Today, those ratios have flipped, Orszag said. He added that if higher education’s share of state budgets had remained constant instead of being crowded out by rising health costs, it would get some $30 billion more than it receives today, or more than $2,000 per student, enough to cover the gap that has opened between private and public universities.

A more detailed econometric analysis showed how this disparity arose. During recessions, when the share of state budgets devoted to health care spending increases significantly, states ratchet down appropriations to higher education and raise tuition (see Figure 4-2). During good times, though, those cuts to higher education are never restored. The traditional answer to this problem has been to raise tuition to offset declining state appropriations, but cutting back state appropriations by 20 percent would require a tuition hike of 80 percent. “That is not going to happen,” Orszag said. The result is that, despite the fact that tuition has been rising significantly, that rise has not been sufficient to offset cuts in state appropriations. However, Orszag noted, primary and secondary education has been sheltered from this trend.

FIGURE 4-2

Net tuition as a percentage of public higher education total educational revenues for fiscal years 1988–2013. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing State Higher Education Executive Officers, 2014.

One possible solution to this problem would be to try to mitigate the impact of upward pressures on Medicaid expenditures during slowdowns in the economy, but this would only lessen the impact of the rise in health care costs that, without some change, will continue to account for an ever-growing share of state budgets. “Ultimately, the only way to really get at this problem is to slow the growth rate in health care spending, because without that, you are going to be making sandcastles on the beach, and it is not really going to work,” Orszag said.

The second point that Orszag made concerning the diminishing support for public universities was that it puts college out of the reach of an increasing number of students, and, as Steven Woolf had pointed out earlier, years of higher education are associated with lower mortality and morbidity in adulthood. This is particularly important because the gap between more educated and less educated people is growing. “We might not care so much about the health effects of education if we felt that everyone had the same access to higher education,” Orszag said, “but we know that is not true,” and he noted that there is also a growing gradient in college completion rates by income even among students who score highly on standardized tests (see Figure 4-3).

FIGURE 4-3

College completion by income status and eighth-grade test scores. NOTE: Low income is defined as the bottom 25 percent, middle income as the middle 50 percent, and high income as the top 25 percent. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing an (more...)

Furthermore, according to the scientific literature, the internal rate of return on college expenditures is about 7 percent in additional wages earned, adjusted for inflation. As a result, not only do those who go to college live longer, but they also make more money for each year that they are alive. In turn, data show that being richer also correlates with a greater decrease in mortality (see Figure 4-4), further compounding the disparity between the more and less educated. The magnitude of these changes over a relatively short period of time is “massive,” Orszag said.

FIGURE 4-4

Change in average additional life expectancy in years at age 55, by income, between cohorts born in 1920 and 1940. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing figure created by Barry Bosworth, Brookings Institution, 2014, available at http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2014/04/18/the-richer-you-are-the-older-youll-get (accessed (more...)

There are difficulties in making conclusions from these data given that there are likely to be differences between a dropout today and a dropout in 1987, and there are likely to be various other selection effects as well, but the fact that so many data sets reveal this same basic phenomenon at least attenuates the concerns that these trends could be driven by selection effects, Orszag said. “It would be a little odd that the selection effect on lifetime earnings was exactly the same kind of thing with regard to education.” Orszag added that the net effect of these growing gaps in disparity means “that we are actually starving low-income kids, not only of income, but of life expectancy extension opportunities because of the growing gradient in educational college completion” (see Figure 4-5).

FIGURE 4-5

Trends in U.S. mortality levels by education for individuals 40 to 64 years old, 1989–2007. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing Miech et al., 2011.

Turning to a trend that is more optimistic, Orszag discussed the potential impact of the recent deceleration in health care spending (see Figure 4-6). It is often forgotten, he said, that between now and 2050 Social Security’s share of the budget is expected to rise from 5 percent to 6 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Furthermore, official projections for Medicare, Medicaid, and other health expenditures predict an increase over the same time period from 5 percent to somewhere between 10 and 20 percent of the GDP. The good news is that health care spending has slowed dramatically over the past 5 to 7 years. There is a raging debate ongoing about how much of the slowdown was structural and how much was the result of the slowdown in the economy, but evidence from Medicare suggests that the slowdown is not being driven only by cyclical forces. “Most Medicare beneficiaries have some type of wraparound insurance so that their net out-of-pocket expenses are low,” Orszag said, “and if you look at Medicare alone, the states that had the biggest increases in unemployment or the biggest decreases in housing prices had zero correlation with the states that had the most significant declines in Medicare spending growth rates.”

FIGURE 4-6

Growth in real per-enrollee health spending by payer. NOTE: Figures for 2013 are estimates. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing Council of Economic Advisers, 2014.

Orszag mentioned recent reports in the media that assert that the slowdown in total health care spending has ended. This assertion is based on the rise in overall health care spending as a proportion of the GDP between the first quarter of 2013 and the first quarter of 2014. The problem with that simple analysis, Orszag said, is that there was something else going on during that period: More people were becoming insured. “This doesn’t say anything about whether the cost for the already insured has accelerated or not. It simply says that if you add a bunch of people to the insurance roles, spending is going to go up,” Orszag said. The real question is what is the underlying trend? The answer to that question is still unclear, though the continued deceleration in Medicare spending has continued well into 2014, he noted. For the first 7 months of the 2014 fiscal year, Medicare spending rose a mere $2 billion, or 0.7 percent. Considering the growth in the number of beneficiaries that occurred over the same 7 months as baby boomers hit age 65, the real growth per beneficiary is highly negative.

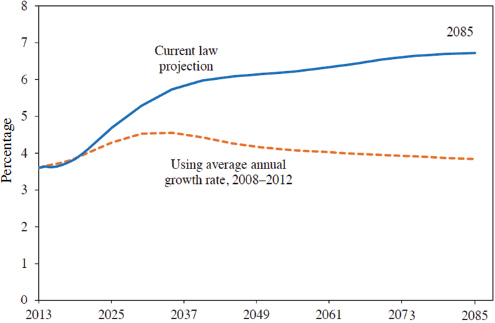

If this trend continues, the impact on the federal budget would be enormous (see Figure 4-7). In fact, if the recent growth rate in Medicare spending is taken as the baseline for projections, the entire rise in Medicare as a share of the GDP would halt, despite the effects of the baby boomers. That in turn would mean that much of the long-term fiscal gap facing the United States would disappear. “If we could simply perpetuate the growth rate in Medicare spending per beneficiary that we have actually experienced over the last 5 years, then everything that you think you know about the nation’s long-term fiscal gap would be wrong,” Orszag said. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office, which Orszag used to run and which he characterized as “not an overly dynamic place that likes to incorporate new information very rapidly into its estimates,” has already taken the 10-year deficit projection and reduced it by $1.2 trillion because of the ongoing deceleration in Medicare and Medicaid spending.

FIGURE 4-7

Projected Medicare spending as a share of GDP, 2013–2085. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, June 5, 2014, citing Council of Economic Advisers, 2013.

The question then becomes whether this trend will continue, and the one caution point is that the nation has experienced this kind of deceleration before (see Figure 4-8). However, this earlier drop in spending was the result of legislation that reduced payment rates to providers and not the result of any systemic change in the health care system. The deceleration seen over the past 5 to 7 years is a result of changing utilization, not because of payment reform or a change in the mix of patients. “The rate of increase in how many things we’re doing to patients is slowing down, which is a much more promising vignette than if it were all done just with price,” Orszag said. “When you just ratchet down provider payments, you can slow nominal spending for some period of time, but it ultimately is not sustainable. The only sustainable way of slowing the growth rate in health care over time is by slowing utilization growth rates. That appears to be what is happening.”

FIGURE 4-8

Annual growth in per-beneficiary spending in parts A and B of Medicare, fiscal years 1980–2012. NOTE: Based on expenditure data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary. SOURCE: Orszag presentation, (more...)

Orszag concluded his presentation by saying that there is a need to pay more attention to policies that can reinforce this trend. When asked what those policies should be, he said that depends on knowing why this deceleration is happening and that his views on this are speculation. One possibility is that hospitals have been successful in reducing readmission rates even though this hurts their profitability, something that he has seen at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, where he is a board member. The reason Mount Sinai and other hospitals are taking these steps regardless of the profit picture today is that these organizations expect the payment system to change over the next 3 to 5 years. “Running an academic medical center is like captaining an aircraft carrier,” he said. “You have got to start turning the ship now, so they are practicing for where they think the payment system will be.”

Given the possibility of the payment system changing soon, the deceleration trend could be reinforced by policies that provide clarity regarding exactly which payment for value policies are likely to take the place of fee-for-service. “We are at a moment where policy makers need to provide a glide path in terms of how we transition away from fee for service and exactly how that is going to work,” Orszag said in response to a follow-up question from Sanne Magnan. “My utter frustration here is that, ironically, both Democrats and Republicans agree on that proposition. Pretty much everyone agrees we are going to have a risk-adjusted, capitated type payment up front with a quality adjuster at the backend. That is like apple pie among the health policy wonks.

“The problem is,” he continued, “Republicans want that payment to go to insurance companies who will then contract with providers to make that a reality. Democrats want the payments to go directly to the provider. That is the big difference.” The irony, he added, is that private insurance companies are moving in this direction anyway and the dividing line between a provider and payer is becoming blurry.

Other steps to reinforce the deceleration trend would be to integrate health care data into a more useful form and making sure employers have the proper incentives that are supported by research. For example, it is commonly believed that people will use exercise facilities more if they are convenient, but there is no research demonstrating that to be true. “If there were compelling studies showing that having a gym in the building makes a massive difference,” Orszag said, “then you could imagine a movement to make sure every major workplace had both a healthy cafeteria and a gym. Today, we are lacking that kind of information.”

DISCUSSION

David Kindig of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health asked Orszag if he was at all optimistic about the possibility that savings in health care will get funneled back into education and the other social areas where investments are needed to drive improvements in population health. Orszag replied that at the state and local levels, the main goal is to make sure that the long-term decline in funding for public higher education is stopped. “I do think that would happen organically if the pressure on state budgets from health spending were attenuated,” he said, though he added that he does not see a plausible scenario under which state appropriations for higher education would increase. At the federal level, he said, the main problem is that neither political party will own up to the revenue base needed to fund everything that the federal government is being asked to do, and the way that this is being dealt with is by placing unrealistic caps on discretionary funding. Although a deceleration in health care spending would solve this problem, Orszag said that, as with the states, he did not hold out great hope for a massive new federal public investment in education.

George Isham of HealthPartners then asked what Orszag thought of a past Institute of Medicine recommendation that the Secretary of Health and Human Services declare a target for life expectancy, establish data systems for a permanent health-adjusted life expectancy target, and establish a specific per capita health expenditure target to be achieved by 2030 with the goal of galvanizing the nation to take action, much as John F. Kennedy did with his goal of putting somebody on the moon by the end of the 1960s. Orszag replied that it is important to have goals, but picking which goal to set is of critical importance. He wondered if setting a mortality rate goal is too ambitious, in part because it is beyond our direct control. He speculated that perhaps setting a goal for total Medicare spending would be more attainable and could be accompanied by a clear statement of what would happen if the nation did not reach that goal. Another goal could be to change the payment system from fee-for-service to outcomes-based. “I’m just nervous about setting a goal at the national level for something not fully under our control,” he said. “If a policy maker wanted to go do that, I would stand up and cheer. As a researcher, I am a little bit nervous about the degree of control that one has over mortality in particular.”

Publication Details

Copyright

Publisher

National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC)

NLM Citation

Roundtable on Population Health Improvement; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine. Exploring Opportunities for Collaboration Between Health and Education to Improve Population Health: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015 Aug 27. 4, How the Nation’s Health Care Expenditures Reduce Education Funding.