NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-.

ABSTRACT

The chapter summarizes the current information available from a variety of scientifically based guidelines and resources on dietary advice for those with diabetes. It is a practical overview for health care practitioners working in diabetes management. The chapter is divided into sections by content and includes sources for further reading. A primary message is that nutrition plans should meet the specific needs of the patient and take into consideration their ability to implement change. Often starting with small achievable changes is best, with larger changes discussed as rapport builds. Referral to medical nutrition therapy (MNT) provided by a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist (RDN) and a diabetes self- management education and support (DSMES) program is highlighted. For complete coverage of all related areas of Endocrinology, please visit our on-line FREE web-text, WWW.ENDOTEXT.ORG.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will summarize current information available from a variety of evidence-based guidelines and resources on dietary advice for those with diabetes. The modern diet for those with diabetes is based on concepts from clinical research, portion control, and individualized lifestyle change. It requires open and honest communication between health care practitioner and patient and cannot be delivered by giving a person a diet sheet in a one-size-fits- all approach. The lifestyle modification guidance and support needed most often requires a team effort, ideally including a registered dietitian (RD) or registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN), or a referral to a diabetes self- management education and support (DSMES) program that includes dietary advice. Current (2024) recommendations of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) promote all health care professionals to refer people with diabetes for individualized medical nutrition therapy (MNT) provided by an RDN at diagnosis and as needed throughout the life span, in addition to DSMES (1). It is very important to note that dietary recommendations for those with diabetes are virtually the same recommendations for diabetes prevention and the health of the general population; however, it cannot be excluded that people with diabetes will require additional support to meet the recommendations.

Fang et al, reported that although there has been continued improvements in risk factor control and adherence to preventative practices over the past decades, half of U.S. adults with diabetes do not meet the recommended goals for diabetes care in 2015-2018 (2). This is a current and ongoing issue. Diet and lifestyle recommendations are cornerstones of advice to prevent and manage diabetes, however there are recognized barriers to heeding advice and implementing lifestyle change. First, there is a plethora of dietary information for diabetes management available from many sources, although not all is evidence-based or current. There are also social, cultural, and personal preferences unique to each individual that must be taken into consideration when making long-term dietary change. Many health care practitioners are not adequately trained to be confident in delivering dietary advice, and many food environments do not support healthy dietary intakes for all. There are also commercial determinants of health that influence dietary intakes, such as marketing advertising, and price discounting on certain foods. The following recommendations come from evidence-based guideline development processes and emphasize practical suggestions for implementing dietary advice for most individuals with diabetes.

GENERAL GOALS

Dietary advice for those with diabetes has evolved and have become more flexible and patient centered over time. Nutrition goals from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2024 include the following: (1)

- 1.

To promote and support healthful eating patterns, emphasizing a variety of nutrient-dense foods in appropriate portion sizes, to improve overall health and:

- a.

achieve and maintain body weight goals.

- b.

attain individualized glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals.

- c.

delay or prevent the complications of diabetes.

- 2.

To address individual nutrition needs based on personal and cultural preferences, health literacy and numeracy, access to healthful foods, willingness and ability to make behavioral changes, and existing barriers to change.

- 3.

To maintain the pleasure of eating by providing nonjudgmental messages about food choices while limiting food choices only when indicated by scientific evidence.

- 4.

To provide an individual with diabetes the practical tools for developing healthy eating patterns rather than focusing on individual macronutrients, micronutrients, or single foods.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) guidelines have similar nutrition goals for people with type 2 diabetes (3).

Putting Goals Into Practice

How should these goals best be put into practice? The following guidelines summarized from the ADA Standards of Care will address the above goals and provide guidance on nutrition therapy based on numerous scientific resources. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and other studies demonstrated the added value individualized consultation with a registered dietitian familiar with diabetes treatments, along with regular follow-up, has on long-term outcomes and is highly recommended to aid in lifestyle compliance (4). Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) implemented by a registered dietitian is associated with A1C reductions of 1.0–1.9% for people with type 1 diabetes and 0.3–2.0% for people with type 2 diabetes (1).

Target Guidelines For Macronutrients: The 3 Major Components Of Diet

Many studies have been completed to attempt to determine the optimal combination of macronutrients. Based on available data, the best mix of carbohydrate, protein, and fat depends on the individual metabolic goals and preferences of the person with diabetes. It’s most important to ensure that total energy intake is kept in mind for weight loss or maintenance (1).

CARBOHYDRATES

The primary goal in the management of diabetes is to achieve as near normal regulation of blood glucose as possible. Both the type and total amount of carbohydrate (CHO) consumed influences glycemia. Carbohydrate intake should emphasize nutrient-dense carbohydrate sources that are high in fiber (at least 14 g fiber per 1,000 kcal) and minimally processed (1). Dietary carbohydrate includes sugars, starch, and dietary fiber. Higher intakes of sugars are associated with weight gain and greater incidence of dental caries (5). Conversely, higher intakes of dietary fiber are associated with reduced non-communicable disease and premature mortality occurrence as well as improvements in body weight, cholesterol concentrations, and blood pressure (6, 7). These benefits with higher fiber intakes have been observed in the general population, for those with type 1, type 2, and pre diabetes, (8) and those with hypertension or heart disease (9). With this guidance in mind, eating plans should emphasize non-starchy vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains, as well as dairy products with minimal added sugars (1, 10). There is less consistency of evidence for recommending an amount of overall CHO in the diet (1). This is in line with current World Health Organization for carbohydrate intakes for adults and children which stress the type of carbohydrate is important, with recommendations for fiber and vegetable and fruit intake, but no recommendations on CHO amount (7). Recent dietary guidelines for diabetes management from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes stress that a wide range of carbohydrate intakes can be appropriate, however both very high (>70%Total Energy (TE)) and low (<40%TE) intakes are associated with premature mortality (10). A recent comprehensive Cochrane systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adults with overweight or obesity with or without type 2 diabetes concluded that there is probably little to no difference in weight reduction and changes in cardiovascular risk factors up to two years' follow-up, when overweight and obese participants without and with T2DM are randomized to either low-carbohydrate or balanced-carbohydrate weight-reducing diets (11). Some of the reasons for these findings of a lack of effect with lower carbohydrate diets may be that: interventions do not consider the type of carbohydrate being consumed, with dietary fiber and sugar having differing physiological effects; the differing definitions of low CHO diets being applied; what CHO is replaced with; and that diets lower in CHO maybe difficult to maintain in the long term as they are not consistent with the socio, cultural, and personal preference of many. Current ADA recommendations relating to CHO are: (1)

- Emphasize minimally processed, nutrient-dense, high-fiber sources of carbohydrate (at least 14 g fiber per 1,000 kcal).

- People with diabetes and those at risk are advised to replace sugar-sweetened beverages (including fruit juices) with water or low-calorie or no-calorie beverages as much as possible to manage glycemia and reduce risk for cardiometabolic disease and minimize consumption of foods with added sugar that have the capacity to displace healthier, more nutrient-dense food choices.

- Provide education on the glycemic impact of carbohydrate, fat, and protein tailored to an individual’s needs, insulin plan, and preferences to optimize mealtime insulin dosing.

- When using fixed insulin doses, individuals should be provided with education about consistent patterns of carbohydrate intake with respect to time and amount while considering the insulin action time, as it can result in improved glycemia and reduce the risk for hypoglycemia.

Dietary Fiber

Current recommendations from the American Diabetes Association are that adults with diabetes should consume high fiber foods (at least 14g fiber per 1,000 kcal) (1). Current recommendations from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes are that adults with diabetes should consume at least 35g dietary fiber per day (or 16.7g per 1,000 kcal) (10). These two values are aligned, and higher than current World Health Organization recommendations for the general population of at least 25g dietary fiber per day, (7) although all three recommendations recognize a minimum intake level, with greater benefits observed with higher intakes. These values are appreciably higher than current dietary fiber intakes in the United States, which is approximately 16g per day. Our understanding of the importance of dietary fiber has changed in recent years. Dietary fiber is carbohydrate that is not digested by the stomach or absorbed in the GI tract. Instead, it is either degraded in the colon by the gut microbiota, or passes through the human body intact. Higher intakes of dietary fiber are associated with lower all-cause mortality, heart disease, T2 diabetes incidence, and certain cancers such colorectal cancer when compared with lower fiber intakes (6). The benefits for childhood intakes of dietary fiber and health outcomes later in life remain uncertain (12). There are several established physiological pathways that might explain these associations, such as reducing postprandial glycemia, competitive inhibition of saturated fat in the small intestine, and greater satiety leading to reduce subsequent intake. There are also more novel pathways proposed, such as modulation of the gut microbiota to increase branched and short chain fatty acids. Current recommendations by the World Health Organization are to obtain “naturally occurring dietary fiber as consumed in food” (7). Fiber supplements however are used frequently as additional dietary fiber sources, and may help individuals reach their fiber recommendations when sufficient amounts cannot be obtained from food alone. Fiber supplements can be extracted fiber (taken from a plant source) or synthetic. Few fiber supplements have been studied for physiological effectiveness to the same degree as inherent dietary fiber, so current best advice is to consume foods that are high in fiber (1, 7, 13). Recommended food sources of dietary fiber are minimally processed whole grains, vegetables, whole fruit and legumes (1, 7). An emphasis on minimally processed is made, as processing may reduce the benefits associated with intakes of these foods, (14-16) as well as introduce added nutrients such as saturated fats, sodium, and added sugars.

The website below contains links to a comprehensive table listing fiber content of foods, and a calculator to help select foods with higher fiber content to help reach daily fiber goals.

http://www.webmd.com/diet/healthtool-fiber-meter. In the Endotext chapter entitled “The Effect of Diet on Cardiovascular Disease and Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels” in the Lipid and Lipoprotein section provides several tables providing information on the fiber content of various foods.

Starch

Starch comprises most of the carbohydrates consumed globally, and is the storage carbohydrate found in refined cereals, potatoes, legumes, and bananas (16). Starch comprises two polymers: amylose (DP ~ 103) and amylopectin (DP ~ 104–105). Most cereal starches comprise 15–30% amylose and 70–85% amylopectin. In their raw form, most starches are resistant to digestion by pancreatic amylase, but gelatinize in heat and water, permitting rapid digestion (16). Dietary starch intake is rarely directly reported, so the health effects of dietary starch intake are often assessed through key sources, such as refined grains and potatoes. For potatoes, meta-analyses of prospective observational studies have identified the health effects are largely determined by the cooking method (17). Fried and salted potatoes were associated with higher incidence of type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Boiled and roasted potatoes were not associated with increased or decreased risk to health (17). Some starches escape digestion, either naturally or due to food processing; these starches are called resistant starches.

Resistant Starches

Resistant starches are starch enclosed within intact cell walls. These include some legumes, starch granules in raw potato, retrograde amylose from plants modified to increase amylose content, or high-amylose containing foods, such as specially formulated cornstarch, which are not digested and absorbed as glucose. Resistant starches avoid digestion in the small intestine so do not contribute to postprandial glycemia and diabetes risk, and are instead fermented in the colon by the microbiota.

Sugars (Nutritive Sweeteners)

Sucrose, also known as “table sugar,” is a disaccharide composed of one glucose and one fructose molecule and provides 4 kcals per gram (16). Available evidence from clinical studies does not indicate that the overall amount of dietary sucrose is related to type 2 diabetes incidence, however it is related to body weight gain and increased dental caries (5). Given the association between excess body weight and type 2 diabetes occurrence, (18) there is rationale to promote a reduction of sugar intake related to diabetes occurrence, and replace sugar-sweetened beverages (including fruit juices) with water or no/low calorie beverages as much as possible (1).

Fructose is a naturally occurring monosaccharide found in fruits, some vegetables, and honey. High fructose corn syrup is used abundantly within the United States in processed foods as a less expensive alternative to sucrose. Fructose consumed in naturally occurring in foods such as fruit, (that also contain fiber) may result in better glycemic control compared with isocaloric intake of sucrose or fructose added to food, and is not likely to have detrimental effects on triglycerides as long as intake is not excessive (<12% energy).

A meta-analysis of 18 controlled feeding trials in people with diabetes compared the impact of fructose with other sources of carbohydrate on glycemic control. The analysis found that an isocaloric exchange of fructose for carbohydrates did not significantly affect fasting glucose or insulin and reduced glycated blood proteins in these trials of less than 12 weeks duration. The short duration is a potential limitation of the studies (19). Evidence exists that consuming high levels of fructose-containing beverages may have particularly adverse effects on selective deposition of ectopic and visceral fat, lipid metabolism, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity compared with glucose-sweetened beverages (20). Thus, recommendations for dietary fructose tend to promote the reduction of fructose added to food, such as in fructose-containing beverages, while promoting whole fruit which can contain intrinsic fructose.

Non-Nutritive Sweeteners

Non-nutritive sweeteners provide insignificant amounts of energy and elicit a sweet sensation without increasing blood glucose or insulin concentrations. There are several FDA-approved sweeteners found to be safe when consumed within FDA acceptable daily intake amounts (ADI) (Table 1) (21).

Table 1.

NON-NUTRITIVE SWEETENERS

| Name | Main Source |

|---|---|

| Sucralose (Splenda®) | Sucralose is synthesized from regular sucrose, but altered such that it is not absorbed. Sucralose is 600 times sweeter than sucrose. It is heat stable and can be used in cooking. It was approved for use by the FDA in 1999. |

| Saccharine (Sugar Twin®, Sweet ‘N Low®) | Saccharine is 200 to 700 times sweeter than sugar. A cancer-related warning label was removed in 2000 after the FDA determined that it was generally safe. |

| Acesulfame K (Ace K, Sunette) | Acesulfame is 200 times sweeter than sucrose. It can be used in cooking. The bitter aftertaste of acesulfame can be greatly decreased or eliminated by combining acesulfame with another sweetener. |

| Neotame | Neotame is a derivative of the dipeptide phenylalanine and aspartic acid. It is 7,000-13,000 times sweeter than sucrose and does not have a significant effect on fasting glucose or insulin levels in persons with type 2 diabetes. |

| Aspartame (Equal®, NutraSweet®) | Aspartame is a methyl ester of aspartic acid and phenylalanine dipeptide. Although aspartame provides 4 kcal/g, the intensity of the sweet taste (200x sweeter than sucrose) means that very small amounts are required. The FDA requires any foods containing aspartame to have an informational label statement: “Phenylketonurics: contains phenylalanine.” Patients with phenylketonuria should avoid products containing Aspartame. Controversy has existed for many years around safety of this sweetener, but not from any major organizations. |

| Stevia (Truvia®) | Stevia derived from the plant stevia rebaudiana, is a non-caloric, natural sweetener. Stevia has been used as a sweetener and as a medicinal herb since ancient times and appears to be well-tolerated. It has an intensely sweet taste. |

| Luo han guo | Luo han guo is also known as monk fruit, or Swingle fruit extract. It is 150- 300 times sweeter than sucrose, and may have an aftertaste at high levels. |

A review of 29 RCTs which included 741 people, 69 of which have type 2 diabetes, indicated that artificial sweeteners on their own do not raise blood glucose levels, but the content of the food or drink containing the artificial sweetener must be considered, especially for those with diabetes (22). This sentiment was echoed in recent WHO guidance on non-nutritive sweeteners for the general population (23) where their use was not recommended for weight loss, as the overall content of the processed food or drink was important.

Practical Tips For Carbohydrate Intake

- Base meals and snacks around high fiber foods, such as whole grains, vegetables, whole fruit, and legumes.

- Common whole grains include whole wheat, whole oats, brown rice, barley, and quinoa.

- When purchasing wholegrain foods, check the label to make sure that the wholegrain is the first ingredient listed, and that energy from sugars is <10%.

- Consume fruit, but chose whole fruit over dried, juiced, or further processed fruit.

- Legumes are an excellent and cheap source of fiber and protein. Replace ground meat in meals such as casserole with lentils or legumes.

- Strive to include a variety of vegetables in your meals each day, avoiding deep fried and heavily salted options.

FAT

Evidence is inconclusive for an ideal amount of total fat intake for people with diabetes; therefore, goals should be individualized.

In line with advice for the general public, people with diabetes should look to replace saturated and trans fats in the diet with mono and poly unsaturated fats (24). This is principally to lessen the increased risk of cardiovascular disease with high saturated and trans-fat intakes. Recent meta-analyses have found that decreasing the amount of saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids, the principal dietary fatty acids linked to elevating LDL cholesterol, reduces the risk of CVD (25). The World Health Organization and American College of Cardiology currently recommend limiting the amount of dietary saturated and trans-fat intake (24, 26). Recommendations from the Institute of Medicine and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics for healthy individuals are that 20% to 35% of total energy should come from fat (27). Recommendations to reduce total fat intake are largely due to the high energy content of dietary fats, more so than protein or carbohydrate, and the risks associated with higher saturated fat intakes. Current recommendations for fat intakes from the American Diabetes Association focus on fat quality and its sources rather than quantity (1). They recommend:

- Counsel people with diabetes to consider an eating plan emphasizing elements of a Mediterranean eating pattern, which is rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats and long-chain fatty acids such as fatty fish, nuts, and seeds, to reduce cardiovascular disease risk and improve glucose metabolism.

The American Heart Association has developed the Fat Facts to help individuals learn more about healthy vs. unhealthy fats. Among the campaign's top priorities is to encourage replacing high trans-fat partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, animal fats, and tropical oils with healthier oils and foods higher in unsaturated fats — monounsaturated and polyunsaturated.

See more at: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/the-facts-on-fats.

Monounsaturated Fatty Acids

Monounsaturated fats (MUFA) are in foods such as avocado, some fish, nuts, and nut butters. MUFA are also found in vegetable oils such as olive, peanut, avocado, and canola oil. Several large prospective observational studies have documented that diets rich in MUFA or PUFA and lower in saturated fat are associated with a reduced risk of CVD (28). Meta-analysis of RCTs comparing diets higher in MUFA vs CHO or PUFA demonstrated that high MUFA containing diets can improve metabolic parameters and reduce cardiovascular disease risk in people with T2D (29, 30).

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) are found in foods such as walnuts, sunflower seeds, and some fish such as salmon, mackerel, herring, and trout. PUFA are also found in vegetable oils such as corn oil, safflower oil, and soybean oil. Both PUFA and MUFA are usually liquid at room temperature. A meta-analysis of feeding trials has indicated consistent positive effects when other macronutrients, such as saturated fats, are replaced with PUFA on glycemia, insulin resistance, and insulin secretion capacity (31). Substitution data from prospective observational studies also indicates that replacing saturated and trans fats with PUFA reduces all-cause mortality and coronary heart disease, (25) with a smaller body of evidence in those with diabetes indicating similar improvements in cardiovascular disease risk (30).

A few specific types of PUFA are referred to as Omega-3 fats. These are called eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). These fats are particularly singled out and recommended to prevent or treat CVD; however, evidence does not support a beneficial role for the routine use of n-3 dietary supplements in diabetes management (1) or for the general population. EPA and DHA are found in fatty fish. ALA is found in nuts and seeds. Studies on the effect of omega-3 fatty acids (both from food and supplements) in persons with diabetes are limited and have been inconclusive (20). In addition to providing EPA and DHA, regular fish consumption may help reduce triglycerides by replacing other foods higher in saturated and trans fats from the diet, such as fatty meats and full-fat dairy products. Preparing fish without frying or adding cream-based sauces is recommended. Fish with high amounts of EPA and DHA include salmon, albacore tuna, mackerel, sardines, herring, and lake trout. Nuts and seeds high in ALA include walnuts, flax seeds, chia seeds and soybeans (16).

Saturated Fats

Saturated fats are usually solid or almost solid at room temperature. All land animal fats, such as those in meat, poultry, and dairy products, are predominantly saturated. Processed and fast foods also contain high amounts of saturated fats. Some vegetable oils also can be saturated, including palm, palm kernel, and coconut oils (16). Oil such as coconut and palm (sometimes referred to as tropical oils) are touted as healthful saturated fats since they are derived from plants, however this is not accurate (25). Current ADA recommendations are to limit all sources of saturated fats (1). The World Health Organization recommends limited consumption of saturated fats to less than 10% of total energy intake, (24) which is far less than the current average intake. When cooking with oil, choose non-tropical vegetable oils such as canola, corn, olive, peanut, safflower, soybean, and sunflower oils (16).

Few research studies have been undertaken to look at the difference between the amount of saturated fatty acids (SFA) in the diet and glycemic control and CVD risk in people with diabetes (30). The ADA recommends people with diabetes follow the guidelines for the general population (20).

In general, saturated fats are discouraged because they increase LDL-cholesterol and total cholesterol concentrations (24). Diets high in saturated fats have been implicated in an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Three RCTs found that diets containing ≤7% SFA and ≤200 mg/day cholesterol reduced LDL cholesterol level from 9% to 12% compared to baseline values or to a more standard Western-type diet (32). As saturated fats are progressively decreased in the diet, they should be replaced with unsaturated fats and high fiber carbohydrates, and not with trans fats or refined carbohydrates (25).

Trans Fats

Trans fatty acids (TFA) are also called hydrogenated fats, which are fats created when oils are "partially hydrogenated" (16). The process of hydrogenation changes the chemical structure of unsaturated fats by adding hydrogen atoms, or “saturating” the fat. Hydrogenation converts liquid oil into stick margarine or shortening. Manufacturers use hydrogenation to increase product stability and shelf-life. A large quantity of these fats can be produced at one time, saving manufacturing costs. Research trials indicate that TFA can increase LDL cholesterol and lower HDL cholesterol (33). Meta-analysis of prospective observational studies indicate higher intakes of trans fats are associated with higher cases of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease (25). Although less prevalent by volume in the food supply, trans fats appear at least as harmful to health as saturated fats (25). Due to the observations from both RCTs and prospective observational studies, the World Health Organization currently recommends that the total intake of trans fats be less than 1% of total energy intake (24). With the mandatory TFA labeling in the United States in 2006, a big push has been made by food manufacturers to remove TFA from processed and baked goods. Although the TFA content in foods has decreased recently (through food reformulation), it is important to monitor the type of fat used to replace TFA, as it might be saturated fat. The FDA has determined that trans fats are no longer considered generally recognized as safe (GRAS). While manufacturers cannot add TFAs to foods anymore, they may still be produced during the food manufacturing, so consumers should still check the nutrition information panel on foods. The main sources of trans fats in the food supply today are highly processed foods such as cakes, cookies, potato chips, and animal products. They can also be produced in the home when frying foods in fat at high temperatures. While most trans fats in the diet now are created during food manufacturing, smaller amounts of trans fats are also found in ruminant animals (cows and sheep). At present there is insufficient evidence to indicate that the health effects differ between trans fats that are created in food manufacturing or ruminant derived, (25) so advice to reduce trans-fat intakes relates to total trans-fat (24).

Cholesterol

The body makes enough cholesterol for physiological functions, so it is not needed through foods. Older dietary guidelines formerly recommended avoiding or limiting consumption of foods high in cholesterol, in the idea that their intake would raise our own circulating cholesterol levels. Now however, it is understood that saturated fat intake has a stronger influence on human cholesterol levels, so recommendations focus on reducing saturated fat as the priority (24).

Table 2.

DIETARY FATS

| Type of Fat | Main Source |

|---|---|

| Monounsaturated | Canola, peanut, and olive oils; avocados; nuts such as almonds, hazelnuts, and pecans; and seeds such as pumpkin and sesame seeds. |

| Polyunsaturated | Sunflower, corn, soybean, and flaxseed oils, and also in foods such as walnuts, flax seeds, and fish. |

| Saturated | Whole milk, butter, cheese, and ice cream; red meat; chocolate; coconuts, coconut milk, coconut oil and palm oil. |

| Trans | Some margarines; vegetable shortening; partially hydrogenated vegetable oil; deep-fried foods; many fast foods; some commercial baked goods (check labels). |

Stanols And Sterols

Plant sterols are naturally occurring cholesterol derivatives from vegetable oils, nuts, corn, woods, and beans. Hydrogenation of sterols produces stanols. The generic term to describe both sterols, stanols, and their esters is phytosterols. An important role of phytosterols is their ability to block absorption of dietary and biliary cholesterol from the gastrointestinal tract. The LDL lowering property of both sterols and stanols is considered equivalent in short term studies (34). The amounts of sterols and stanol esters found naturally in a normal diet are insufficient to have a therapeutic effect. Thus, many manufacturers add them to various foods for their LDL cholesterol lowering effects. You can find added phytosterols in margarine spreads, juices, yogurts, cereals, and even granola bars. Individuals with diabetes and dyslipidemia may be able to reduce total and LDL cholesterol by consuming at least 2 grams per day of plant stanols or sterols found in enriched foods (20). The evidence on long term use and in people with diabetes is less substantiated, as not many studies have been completed (35).

Practical Tips On Fat Intake

- Fat intake should come primarily from good sources of mono and polyunsaturated fats: nuts and seeds, avocados, fish, and oils such as olive, canola, soybean, sunflower, and corn.

- Limit intake of saturated fats by cutting back on processed and fast foods, red meat, and full-fat dairy foods. Try replacing red meat with beans, nuts, skinless poultry, and fish whenever possible, and switching from whole milk and other full-fat dairy foods to lower fat versions.

- In place of butter or margarine, use liquid vegetable oils rich in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats in cooking and at the table.

- Keep trans-fat intakes as low as possible. Check food labels for trans fats, and limit fried foods.

PROTEIN

Protein intake goals should be individualized based on an individual’s current eating patterns. The ADA Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2024 state that there is no evidence that adjusting the daily level of protein intake (typically1–1.5 g/kg body weight/day or 10–20% total energy) will improve health in individuals without diabetic kidney disease, and research is inconclusive regarding the ideal amount of dietary protein to optimize either glycemic control or cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (1). Some research has found successful management of weight and type 2 diabetes with meal plans including slightly higher levels of protein (23–32% total energy) for periods up to one year for those without kidney disease (10). Those with diabetic kidney disease (with albuminuria and/or reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate) should aim to maintain dietary protein at the recommended daily allowance of no more than 0.8g/kg desirable body weight/day (or 10-15% total energy) (10). The National Kidney Foundation recommends 0.8 g protein/kg desirable body weight for people with diabetes and stages 1–4 chronic kidney disease as a means of reducing albuminuria and stabilizing kidney function (36). Reducing the amount of dietary protein below 10% total energy is not recommended as it places people at risk of protein inadequacy (10).

The ADA recommends that in individuals with type 2 diabetes, ingested protein can increase insulin response without increasing plasma glucose concentrations. Therefore, carbohydrate sources high in protein should not be used to treat or prevent hypoglycemia (1). Further research is required to identify if the dietary source of protein (animal or plant) is important for health and diabetes. There is emerging evidence to suggest that plant sourced proteins may be superior for health, (1) however it is not yet known if this is due to the amino acid compositions of the proteins or unadjusted effects from the accompanying nutrients, such as saturated fats in meat sources and dietary fiber in plant sources of protein. Replacement of red meat in the diet with plant-based protein sources (such as beans and legumes) appears to produce both health and environmental co-benefits, as well as being cheaper (37-39).

Practical Tips For Protein Intake

- Ideal plant protein sources include legumes, lentils, tofu, and tempeh (1/2c = 2 oz protein). Plant-based meat alternatives maybe also be used (i.e. Quorn), but be wary of meat alternatives that have high sodium and saturated fat content.

- Nuts or seeds are another plant-based protein source to be encouraged, such as almonds, cashews, hazelnuts, filberts, Brazil nuts, macadamias, peanuts, pecans, walnuts, or sunflower, pumpkin seed or linseed. Nut butters are also a plant-based protein source but be mindful of added sodium and sugars.

- Good sources of lean animal protein include: skinless poultry, lower fat cuts of beef or pork, fish or egg, and reduced fat dairy products (i.e. low fat or skim milk/yogurt, and cheese).

- Protein sources should be a supplement to vegetables, fruits and whole grains for most meals, and not the entire meal.

TARGET GUIDELINES FOR MICRONUTRIENTS

There is no clear evidence that dietary supplementation with vitamins (such as Vitamin D), minerals (such as chromium), herbs, or spices (such as cinnamon or aloe vera) can improve outcomes in diabetes management where there are no underlying deficiencies. There is insufficient evidence for dietary supplements to be recommended for the purposes of improving glycemic control (1).

People with diabetes should be aware of the necessity for meeting vitamin and mineral needs from natural food sources through intake of a balanced diet. Specific populations, such as older adults, pregnant or lactating women, strict vegetarians or vegans, and individuals on very low energy diets may benefit from a multivitamin mineral supplement (1). Excessive doses of certain vitamin or mineral supplements when there is no deficiency has been shown to be of no benefit and may even be harmful. There is some evidence that those on metformin therapy are at higher risk of B12 deficiency and may need Vitamin B12 supplementation if tests indicate a deficiency (1, 40).

VITAMINS

Since type 2 diabetes is a state of increased oxidative stress, interest in recommending large doses of antioxidant vitamins has been high. Current studies demonstrate no benefit of carotene and Vitamins E and C in respect to improved glycemic control or treatment of complications. Routinely supplementing the diet with antioxidant supplements is not recommended due to lack of evidence showing benefit in large, placebo-controlled clinical trials and concerns regarding potential long-term safety (1, 40). There is also not adequate evidence to recommend routine Vitamin D supplementation without deficiency (1, 41).

MINERALS

Sodium

As for the general population, those with diabetes should limit sodium consumption to 2,300 mg/day (20, 42). Active steps to reduce current sodium intakes is necessary, as current intakes in the United States are around 3,400 mg/day, nearly 50% more than the recommended limit. The majority of sodium consumed is from processed foods. Food manufacturers and restaurants will need to provide additional reduced sodium alternatives to help accomplish consumption targets. For those with diabetes and hypertension, additional lifestyle modification beyond reducing sodium intake can be helpful, including: loss of excess body weight; increasing consumption of vegetables and fruit (8 –10 servings/day), and low-fat dairy products (2–3 servings/day); avoiding excessive alcohol consumption (no more than 2 servings/day in men and no more than 1 serving/day in women); and increasing physical activity levels. These nonpharmacological strategies may also positively affect glycemia and lipid control (20). The DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, which is high in vegetables and fruit, low-fat dairy products, and low in saturated and total fat; has been shown in large, randomized, controlled trials to significantly reduce blood pressure (43).

Magnesium

Studies in support of magnesium supplementation to improve glycemic control are unclear and complicated by differences in study designs as well as baseline characteristics. There is some evidence from observational data that higher dietary intake of magnesium may help prevent type 2 diabetes in both middle aged men and women at higher risk for developing the disease (44). Additional long-term studies are needed to determine the best way to assess magnesium status and how magnesium deficiency impacts diabetes management, however dietary sources of magnesium include nuts, whole grains, and green leafy vegetables can be encouraged as part of a healthy dietary pattern.

Chromium

Several studies have demonstrated a potential role for chromium supplementation in the management of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. According to the ADA position statement, the findings with more significant effects were mainly found in poorer quality studies, limiting transferability of the results. Routine supplementation of chromium is therefore not recommended for treating diabetes or obesity (45).

HERBAL SUPPLEMENTS

There has been interest in the past several years on the effect of cinnamon, curcumin, and other herbs and spices in individuals with diabetes. The most recent ADA Lifestyle Management recommendations conclude that after a review of the evidence, there is not enough clear data to substantiate recommending the use of herbs or spices as treatment for T2D (1). The ADA also states that the use of any herbal supplements, which are not regulated and vary in content, may provide more risk than benefit, in that herbs may interact with other medications that are taken to control diabetes (20).

PROBIOTICS

Probiotics (from pro and biota, meaning "for life"), are certain kinds of “good” bacteria found in fermented foods, such as yogurt, kefir, and kimchi and are available as supplements. They are naturally found in the gut and may be depleted due to poor diet, use of antibiotics, smoking, etc. Probiotics have been studied extensively to improve gut flora for use in treatment and possibly prevention of various disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome, diarrhea, constipation, and genitourinary infections, to name a few. Different strains and amounts may work better for some conditions over others, but the FDA does not oversee the supplements, so content and effectiveness are not regulated. They are generally considered safe, as they are found naturally in the digestive tract.

Some research has been done in people with gestational and type 2 diabetes using probiotic supplements and foods to determine if chronic inflammatory and glycemic markers can be improved (46). The premise is that the microbiota may be connected to glucose metabolism by altering insulin sensitivity and inflammation. At present there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations for people with diabetes to take a probiotic for glycemic control.

ALCOHOL

Updated guidelines recommend there is no safe level of alcohol consumption (10). Adults with diabetes who chose to drink alcohol should do so in moderation (no more than one drink per day for adult women and no more than two drinks per day for adult men). Alcohol consumption may place people with diabetes at increased risk for hypoglycemia, especially if taking insulin or insulin secretagogues. Education and awareness regarding the recognition and management of delayed hypoglycemia due to alcohol with or without a meal are warranted. Risks of excessive alcohol intake include hypoglycemia (particularly for those using insulin or insulin secretagogue therapies), weight gain, and hyperglycemia (for those consuming excessive amounts). Hypoglycemia can occur through several mechanisms, including the inability of alcohol to be converted into glucose, the inhibitory effect of alcohol on gluconeogenesis, and its interference in normal counter regulatory hormonal responses to impending hypoglycemia. To decrease the risk of alcohol induced hypoglycemia, it is best to have the alcohol with food. Consuming alcohol in a fasting state may contribute to hypoglycemia in people with type 1 diabetes. Symptoms of hypoglycemia can be similar to drunkenness. When calculating the need for meal related boluses of insulin, one should account for the carbohydrate content of the alcohol if drinking sweet wines, liqueurs, or drinks made with regular juice or soda.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER- FOR TYPE 1 DIABETES AND THOSE ON INSULIN

People taking insulin should be counseled on the importance of balancing food and beverage intake with timing and dosing of insulin. This is especially important for individuals with varied or hectic schedules such as shift workers, people that travel frequently, or anyone who has a schedule in which timing of meals and access to food is irregular (20). Numerous materials and resources are available that can be provided to people with diabetes to help them consider portion control, consistency in food intake and medication dosing, as well as planning to allow some flexibility in their daily self-care regimen (47). Ongoing support from a referral to medical nutrition therapy conducted by a registered dietitian (RD) or registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN), or a referral to a diabetes self- management education (DSMES) program that includes dietary advice is highly effective. The health care provider should provide individualized guidelines for a target blood glucose range, considering safety and health. For motivated people, teaching an insulin to CHO ratio, and blood glucose correction factor may assist them with achieving blood glucose targets and achieving better glycemic control (1).

CARBOHYDRATE COUNTING

Carbohydrate counting is a tool that can be taught to the motivated, so that they can more easily estimate the amount (grams) of CHO in a particular food and adapt their insulin therapy accordingly (48). Furthermore, setting a target CHO intake for each meal allows those with diabetes to better match their CHO intake to the appropriate mealtime insulin dose. Potential advantages of CHO counting include improved glucose control, flexibility in food choices, a better understanding of how much insulin to take, and simplification of meal planning (49).

Carbohydrate (CHO) intake affects acute blood glucose levels. Monitoring carbohydrate, whether by carbohydrate counting, using the exchange method, or experienced- based estimation, remain an important strategy used in timing of medication administration and improving glycemic control (20). CHO counting methodology is based on the concept that each serving of CHO equals approximately 15 grams of CHO. Generally, blood glucose response to digestible carbohydrate is similar, however carbohydrate sources naturally high in fiber including whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and whole fruits should be encouraged over highly processed foods, fruit juices, and sweetened beverages. Insulin dosing also needs to be adjusted based on the protein and fat content of the mail as well, as high levels of either can slow down digestion and glucose uptake into circulation. On average woman require about 3-4 servings (45-60 grams), while men may need 4-5 servings (60-75 grams) of CHO at each meal (47). This number could vary depending on individual energy needs (i.e., pregnant/nursing, ill, etc.), medication, and level of physical activity.

A good online resource for basic carbohydrate counting can be found on the UCSF website:

https://dtc.ucsf.edu/living-with-diabetes/diet-and- nutrition/understanding-carbohydrates/counting- carbohydrates/

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR THOSE WITH INTENSIVE INSULIN REGIMENS

The following guidelines are the starting point for the nutritional component of intensified insulin management regimens for those not on closed loop systems: (1, 50)

- The initial diabetes meal plan should be based on the individual’s normal intake with respect to calories, food choices, and times of meals eaten.

- Choose an insulin regimen that is compatible with their normal pattern of meals, sleep, and physical activity.

- Synchronize insulin with meal times based on the action time of the insulin(s) used.

- Assess blood glucose levels prior to meals and snacks and at bedtime and adjust the insulin doses as needed based on intake.

- Monitor A1C, weight, lipids, blood pressure, and other clinical parameters, modifying the initial meal plan as necessary to meet goals.

- It is also important to educate those with diabetes on adjustment of prandial insulin considering premeal glucose levels, carbohydrate intake, and anticipated physical activity.

- For those with diabetes who are overweight and on insulin, counseling on nutrition, weight management, and monitoring blood glucose continues to be important components of treatment. Medical nutrition therapy is recommended with continued emphasis on making lifestyle changes to achieve a weight loss of 5% or more to reduce the risk of chronic complications associated with diabetes, CVD, and other risk factors that contribute to early mortality.

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

While medical nutrition therapy provided by registered dietitians resulted in better glycemic control in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes, a survey of 45 pediatric clinics revealed that only 25 clinics had an experienced pediatric/adolescent dietitian available for children with diabetes (51). Registered Dietitian Nutritionists who are trained and experienced with children and adolescent diabetes management should be involved in the multidisciplinary care team (52). The goals of nutrition therapy for children and adolescents with diabetes include the following: (1, 52)

- Provide individualized nutrition therapy with guidance on appropriate energy and nutrient intake to ensure optimal growth and development.

- Assess and consider changes in food preferences over time and incorporate changes into recommendations.

- Promote healthy lifestyle habits while considering and preserving social, cultural, and physiological well-being.

- Achieve and maintain the best possible glycemic control.

- Achieve and maintain appropriate body weight and promote regular physical activity.

Dietary Advice Should Start Gradually

- Emphasis should initially be on establishing supportive rapport with the child and family with simple instructions. More detailed guidelines should be administered later by the entire team, with focus on consistency in message, and should include dietary guidelines to avoid hypoglycemia. Instruction on carbohydrate counting should be provided as soon as possible after diagnosis (52).

- Nutritional advice needs to be given to all caregivers; babysitters, and extended family who care for the child.

- Nutrition guidelines should be based on dietary history of the family and child’s meal pattern and habits prior to the diagnosis of diabetes and focus on nutritional recommendations for reducing risk of associated complications and cardiovascular risk that are applicable to the entire family.

- Physical activity schedules need to be assessed, along with 24-hour recall, and 3-day food diary to determine energy intake. Growth patterns and weight gain need to be assessed every 3-6 months and recommended dietary advice adjusted accordingly (51).

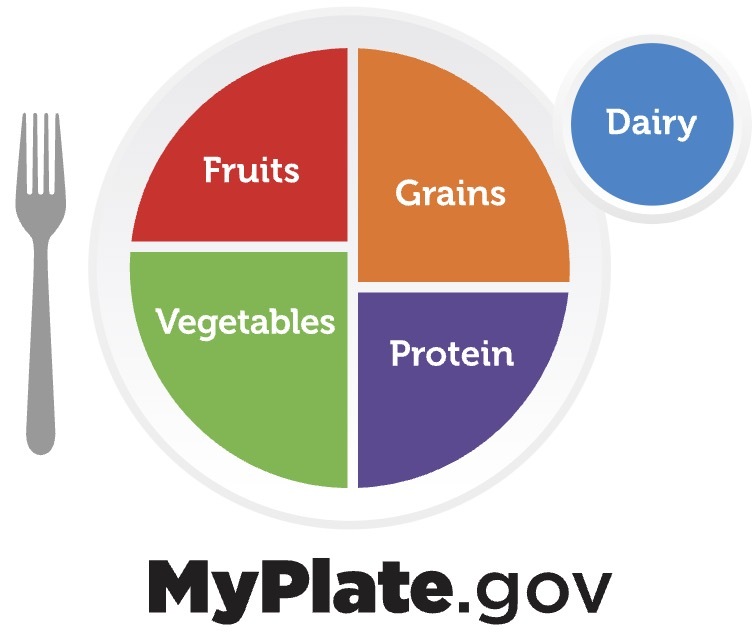

Dietary recommendations can be illustrated by use of the Plate method. There are numerous resources for visuals and educational materials using the plate method and some are specific to diabetes. Half the plate should consist of vegetables and fruit, while the other half is divided between whole grains and lean sources of protein. The dairy is represented by a glass of nonfat or 1% milk or other nonfat or low-fat dairy source. The general guidelines for macronutrients are similar to that of the adult population with diabetes (1, 10).

Figure 1.

Choosemyplate.gov. Video and print materials can be found on the website.

PREVENTION OF HYPOGLYCEMIA

Hypoglycemia usually occurs when taking insulin, or when taking a sulfonylurea. To help prevent hypoglycemia, the following guidelines should be discussed:

- Don't skip or delay meals or snacks. If taking insulin or sulfonylurea, be consistent about the amount eaten and the timing of meals and snacks.

- Monitor blood glucose closely.

- Measure medication carefully, and take it on time. Take medication as recommended by the physician coordinating diabetes care.

- Adjust medication or eat additional snacks if physical activity increases. The adjustment depends on the blood glucose test results and on the type and length of the activity.

- Eat a meal or snack if choosing a drink with alcohol. Drinking alcohol on an empty stomach can contribute to hypoglycemia.

- Record low glucose reactions. This can help the health care team identify patterns contributing to hypoglycemia and find ways to prevent them.

- Carry some form of diabetes identification so that in an emergency others will know you have diabetes. Use a medical identification necklace or bracelet and wallet card.

SICK DAY MANAGEMENT

Eating and drinking can be a challenge when sick. The main rules for sick day management are:

- Continue to take diabetes medication (insulin or oral agent).

- Self-monitor blood glucose.

- Test urine ketones.

- Eat the usual amount of carbohydrate, divided into smaller meals and snacks if necessary.

- Drink non-caloric, caffeine free fluids frequently.

- Call the diabetes care team.

See more at: https://diabetes.org/getting-sick-with-diabetes/sick-days.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Regular physical activity has many health benefits. For individuals with diabetes, these benefits outweigh potential risks. Physical activity can improve glycemic control (1). People with diabetes should be encouraged to undertake regular physical activity to improve cardiovascular and overall fitness, weight control, and for improved psychological well-being and quality of life (20). Physical activity can be considered in terms of duration, intensity, modality, and regularity. The largest potential risks due to physical activity for people with diabetes relates most to the intensity of activity. Low intensity physical activity is safer than high intensity physical activity, and highly beneficial for those with diabetes. People with diabetes are encouraged to undertake at least 30 minutes physical activity each day, with modalities such as walking recommended. There is some evidence that walking is more beneficial to glycemia when undertaken within the two hours after meals, (53) as the skeletal muscles take glucose out of circulation to use as fuel. High intensity physical activity should be discussed first with the diabetes care team due to the potential risk of hypoglycemia and cardiovascular strain. To summarize, there are several factors that can affect the blood glucose response to physical activity: (54)

- Individual response to physical activity varies.

- Duration, intensity, modality, and regularity of physical activity.

- Timing and type of the previous meal.

- Timing and type of the insulin injection or other diabetes agent.

- Pre-physical activity blood glucose level.

- Person’s fitness level.

In individuals taking insulin, blood glucose monitoring is necessary to adjust insulin dosing and carbohydrate intake to reduce hypoglycemia due to physical activity. To reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, when higher intensity physical activity is planned, it may be preferable to adjust the dose of insulin before the activity begins. On the other hand, if the physical activity is unplanned, blood glucose should be checked and a carbohydrate snack can be eaten as needed before the activity begins. If the blood glucose is less than 100mg/dL, a 15- to 30-g carbohydrate snack should be consumed, and glucose should be rechecked in 30 to 60 minutes. If glucose levels are less than 70 mg/dL, physical activity should be postponed. Depending on the blood glucose level at the start of physical activity, as well as duration and intensity of the activity, a snack may need to be consumed before, during and after the physical activity. Moderate intensity physical activity can increase glucose uptake significantly, which may require an additional 15 grams of carbohydrate for every 30-60 minutes of exercise above the normal routine (54).

Physical activity can increase the rate of absorption of insulin into limbs, especially when it is started immediately after the insulin injection. Inject insulin into a less-active area, such as the abdomen, to minimize the effect of physical activity on insulin absorption. Guidelines for glucose management with exercise exist for those with type 1 diabetes (55). The response to physical activity varies greatly in every individual, so adjustment in medication and food should be based on individual responses. Blood glucose monitoring is very important in understanding response patterns and tailoring a physical activity program (56).

TIMING OF INSULIN AND MEALS

The greatest risk for hypoglycemia results when the peak insulin action does not coincide with the peak postprandial glucose. For example, the longer duration of action of regular insulin may lead to increased risk of late postprandial hypoglycemia, compared with rapid-acting insulin analogs, which peak closer to meal consumption. In addition, when the pre-meal insulin dose is too large for a particular meal relative to its CHO content, hypoglycemia can result. Such a mismatch may occur due to errors in estimating CHO or food intake. Insulin calculations can be based on exchanges, carbohydrate counting, or predefined, set menus. If meals and the insulin regimen remain constant, then no problems will usually result. However, any changes in insulin or food intake require adjustment of one or the other, or both. Whatever regimen is employed, it must be individualized. Those taking rapid-acting insulin may choose to give their insulin dose after the meal, if unsure of amount of food to be consumed. This approach can be especially helpful in children or in nausea related to pregnancy or illness. If a smaller than normal meal is eaten, guidelines are available for reducing the insulin dose, or carbohydrate replacement in the form of fruit or fruit juice can be given, depending on the particular insulin regimen (57).

HYPOGLYCEMIA TREATMENT GUIDELINES

Hypoglycemia is defined as a low blood glucose level ≤70 mg/dL. Symptoms include anxiety, irritability, light- headedness and shakiness. Advanced symptoms include headache, blurred vision, lack of coordination, confusion, anger, and numbness in the mouth. Hypoglycemia must be treated immediately with glucose. Follow the 15/15 rule: take 15 grams of simple carbohydrate which should increase blood glucose by 30-45 mg/dL within 15 minutes. When blood glucose dips below 70 mg/dL and oral carbohydrate can be administered, have one of the following "quick fix" foods right away to raise the glucose:

- Glucose tablets (see instructions).

- Gel tube (see instructions).

- 4 ounces (1/2 cup) of juice or regular soda (not diet).

- 1 tablespoon of sugar, honey, or corn syrup.

- Hard candies, jellybeans, or gumdrops, see food label for how many to consume.

High-fat foods will delay peak of glucose levels from carbohydrate intake and should be avoided (e.g., treatment of hypoglycemia with chocolate bars). After 15 minutes, blood glucose should be checked again to make sure that it is increasing. If it is still too low, another serving is advised. Repeat these steps until blood glucose is at least 70 mg/dL. Then, a snack should be consumed if it will be an hour or more before the next meal.

Those who take insulin or a sulfonylurea should be advised to always carry one of the quick-fix foods with them, when driving, and also have available nearby when sleeping. Wearing a medical ID bracelet or necklace is also a good idea, as is having a glucagon emergency kit or nasal spray on hand and knowing how to administer, as well as training close contacts to administer as well.

WEIGHT LOSS FOR THOSE WHO WISH TO LOSE WEIGHT

While the general principles discussed so far apply to all people with diabetes, those with type 2 diabetes who are overweight or obese (BMI >25 kg/m2 or >23 kg/m2 for Asians) and wish to lose weight can require greater support to do so. Consistent evidence has indicated that intentional weight loss reduces blood glucose in people with type 2 diabetes, and improves most other major cardiometabolic risk factors (58, 59). Clinical guidelines state that weight loss through nutrition and physical activity are fundamental to type 2 diabetes management (60, 61). However, with so many weight loss “diets” available, confusion abounds and reinforces the absolute importance that health professionals provide consistent, evidence-based advice. It is also important to have realistic expectations about the speed at which weight is lost. Obesity does not occur overnight, and its treatment requires long term adjustments to energy intake and expenditure.

Many randomized, controlled trials and meta-analyses of trials have been undertaken and to ascertain which macronutrient combination leads to greater weight loss. A two-year head- to-head trial comparing four weight loss diets with differing macronutrient content concluded that all four reduced energy diets, regardless of macronutrient content, led to comparable modest weight loss with weight regain over time (62). This finding was reinforced by a recent comprehensive Cochrane systematic review of RCTs of adults with overweight or obesity with or without type 2 diabetes (11). This review concluded that there is probably little to no difference in weight reduction and changes in cardiovascular risk factors up to two years' follow-up, when overweight and obese participants without and with T2DM are randomized to either low-carbohydrate or balanced-carbohydrate weight-reducing diets. The understanding that focusing on reducing energy intake overall, rather than through a specific macronutrient, frees up weight loss advice so that it can be tailored to the individual’s personal, cultural, and social norms. In this context, understanding reasons for eating, portion size, the energy density of different foods, and factors that promote satiety such as high fiber intakes become essential for achieving and maintaining weight loss.

The most important variable in selecting a weight loss plan is the ability of the individual to follow it over the long term. Developing an individualized weight loss program together, preferably with a registered dietitian nutritionist familiar with diabetes management, along with regular follow-ups, will help promote and maintain weight loss. Initial physical activity recommendations alongside dietary changes should be moderate, gradually increasing the duration and frequency to at least 30 minutes a day of activities such as walking.

Current evidence indicates that ‘low’, and ‘very low’ energy diets using total or partial diet replacement formula diet products are highly effective for weight loss and reduction of other cardiometabolic risk factors when compared with food-based weight-loss diets (63-65). Furthermore, low-energy nutritionally complete formula diets with a ‘total diet replacement’ induction phase are the most effective dietary approach for achieving type 2 diabetes remission (65-67). Comparing ‘low’ with ‘very-low’ energy diets, many people find very-low-energy diets (420–550 kcal/day) difficult to sustain, and they do not generate greater weight loss than formula diets providing ~810 kcal/day (63, 65).

While fast weight loss is a highly desirable outcome, the ultimate health benefits from weight management are likely to depend on long-term weight loss maintenance (10). Long-term low-intensity structured programs, including support for changing food choice, eating pattern and physical activity, and psychological support for behavior change, can help to sustain new behaviors, relationships with foods and adherence to dietary advice, and thus improve weight-loss maintenance (68, 69). Given that dietary adherence can be socially and psychologically testing, skills and empathy from the health professional is needed, providing consistent, long-term, evidence-based support (70). Discussions with patients around weight loss should be entered into with their permission (71) and are important, given the prevalence of obesity (72) and its connection to diabetes incidence (18).

MEAL PLANNING APPROACHES

There is no one “diet” for diabetes. There are, however, many meal planning guidelines available for the people with diabetes. Listed in the information below are some of the meal planning approaches available.

Choose My Plate

Choose My Plate contains general, simple guidelines for healthy eating using a small plate to visually illustrate foods and portion control. Print materials and videos from the USDA are available at www.choosemyplate.gov and The Joslin Diabetes Center https://www.joslin.org/info/diabetes-and-nutrition.html

Diabetes Place Mat

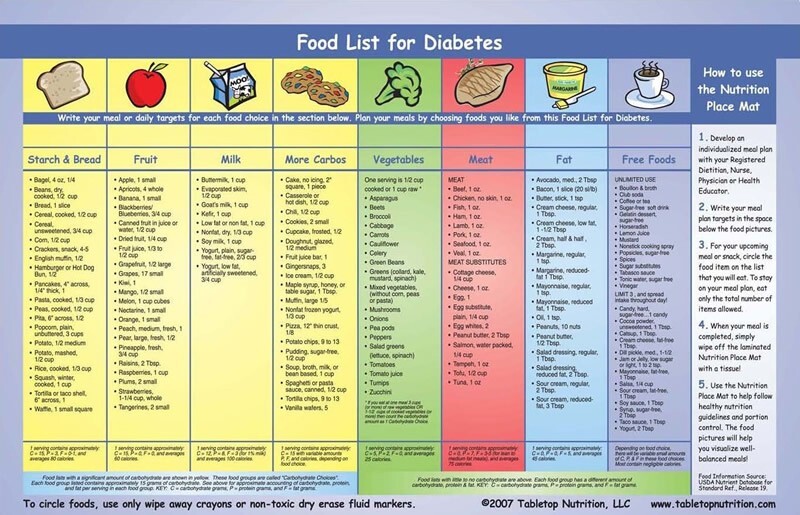

Figure 2.

Nutrition PlaceMat for Diabetes. A sturdy, heavily laminated, 11" by 17" place mat that can be easily used over and over to apply the meal plan.

One side of the Diabetes Place Mat lists food choices and individual portion sizes for each food category of the meal plan. This list replaces easily misplaced or damaged paper lists. When planning the meal, a wipe-off marker is used to write down the number of servings for each food category, as indicated on the plan. Then circle or tally the food choices in each category to track progress toward the plan’s targets. Carbohydrate categories - starch and bread, fruit, milk and other carbohydrates - which affect blood glucose and which can be exchanged for each other, are color coded in yellow for easy identification and proper selection. Other food categories - vegetables, meat, fat and free foods - are individually color-coded.

The other side of the Diabetes Place Mat illustrates the "Plate Method" of managing a diet for proper nutrition and control of blood glucose and weight. It shows the proportions of each food category that are appropriate for a healthy, balanced diet. The food groups shown on the top half of the Plate Method side are carbohydrates, which affect blood glucose the most - fruit, milk, and starch & bread. These are colored in yellow to distinguish them from the other food groups that don't significantly affect blood glucose (meat, vegetables, fat and free foods). The food categories are shown in proportion to how much of each might be eaten in a healthy, balanced diet. The plate method is a great plan for those who have poor math or reading skills or are non- English speaking.

Mediterranean-Style Eating

The Mediterranean-style eating pattern derived from the Mediterranean region of the world has been observed to improve glycemic control and cardiovascular disease risk factors. The Mediterranean eating pattern includes:

- Vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, legumes, potatoes, whole grains, breads, herbs, spices, fish, seafood and extra virgin olive oil. Emphasis is placed on use of minimally processed foods, seasonal fresh and locally grown foods.

- Olive oil is the primary fat, replacing other fats and oils (including butter and margarine).

- Fresh fruit as daily dessert; sweets only rarely.

- Low-to-moderate amounts of cheese and yogurt.

- Red meat limited to only 12 oz to 16 oz per month.

DASH Eating Plan

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) is a flexible and balanced eating plan that is based on research studies sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The DASH diet emphasizes vegetables, fruit, fat-free or low-fat dairy, whole grains, nuts and legumes, and limit the intake of total and saturated fat, cholesterol, red and processed meats, sweets and added sugars, including sugar-sweetened beverages. Results from RCTs indicate reductions in glycemia, blood pressure, body weight, and -cholesterol concentrations (73). In prospective cohort studies the DASH diet is associated with reductions in the risk of CVD, CHD and stroke (73). DASH is considerably lower in sodium than the typical American diet.

Intermittent Fasting

The popularity of intermittent fasting has increased recently as a new way to lose weight and possibly lead to better control of Type 2 diabetes. There are many suggested types of intermittent fasts; some involve eating only on specific days, or not eating for a specified number of hours, alternated by day or hours in which food consumption is allowed. Others greatly restrict energy intake on some days but allow a more normalized diet on other days. There is no one specific intermittent fasting diet that has been proven to be beneficial. Since energy intake is restricted for certain periods of time, an individual with diabetes may lose weight over time if they maintain an overall energy deficit in relation to energy expenditure as is seen with any successful weight loss method.

For people with diabetes who are interested in intermittent fasting, current ADA guidance considers time-restricted eating or shortening the eating window adaptable to any eating pattern, and largely safe for adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes (1, 22). However, anti-hyperglycemic medication use must be considered (74). For those on insulin or taking other anti-hyperglycemia medications, intermittent fasting may lead to hypoglycemic events that may become severe when medications are not adjusted down (75). Careful monitoring of blood glucose is required, and medication adjustment may be necessary. Overall, the simplicity of intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating may make these useful strategies for people with diabetes who are looking for practical eating management tools (1).

Gluten Free

Gluten is a protein commonly found in wheat, barley, rye, and other grains. A gluten free diet is essential to treat people with celiac disease. Celiac disease is an inflammatory condition in persons who are intolerant to gluten and suffer inflammatory and gastrointestinal side effects when gluten is consumed, leading to damage of the small intestine. It is noted that approximately 10% of people with type 1 diabetes also have celiac disease, which is significantly higher than the general population (1-2%). There seems to be no connection with Celiac disease and type 2 diabetes (76). There is no evidence of health benefits when avoiding gluten for those without celiac disease.

The gluten free diet has recently grown in popularity in persons who identify as gluten sensitive, but don’t have celiac disease. According to the ADA, people with T1D can follow a gluten free diet should they wish to, but it may provide additional challenges. Common CHO containing foods that do not contain gluten are: white and sweet potatoes, brown and wild rice, corn, buckwheat, soy, quinoa, sorghum, and legumes. These foods can be used in place of gluten containing grains.

MAYO Clinic Diet

Developed by the Mayo Clinic, a two-phase approach to lose and maintain body weight using the Mayo Clinic food pyramid. For more information see: https://diet.mayoclinic.org/diet/how-it-works.

Jenny Craig®

The plan emphasizes restricting energy, fat, and portions. Jenny's prepackaged meals and recipes do all three, plus emphasize healthy eating, an active lifestyle, and behavior modification. Personal consultants guide members through their journeys from day one. You'll gain support and motivation, and learn how much you should be eating, what a balanced meal looks like and how to use that knowledge once you graduate from the program. Jenny Craig offers two programs: its standard program and Jenny Craig for Type 2, which is designed for people with Type 2 diabetes by including a lower-carb menu, reinforcement of self-monitoring of blood glucose levels, consistent meals and snacks, and other self-management strategies for weight loss and support for diabetes control. Because you buy foods, this program can be more expensive, but convenient for some. For more information see: https://www.jennycraig.com/.

Vegan Diet

Veganism excludes all animal products from the diet – including dairy and eggs. Fruits, vegetables, leafy greens, whole grains, nuts, seeds and legumes are the staples. It is restrictive, but beneficial for the cardiovascular system.

Weight Watchers®

The Weight Watchers assigns every food and beverage a point value, based on nutritional content and provides users with a maximum number of points they can consume per day. A backbone of the plan is multi-model access (via in-person meetings, online chat or phone) to support from people who lost weight using Weight Watchers, kept it off and have been trained in behavioral weight management techniques. For more information see: https://health.usnews.com/best-diet/weight-watchers-diet

Individualized Menus Provided by a RD/RDN

Many people with diabetes might like to have examples to follow when setting up meal plans. The menu describes in writing what foods and what quantities should be consumed over a period of days. A dietitian creates an individualized menu based on the specific nutritional counseling plan and incorporates the client’s unique preferences, schedule, etc. The client then has written examples to follow, and over time may learn how to independently create their own menus and substitutions to fit their individual lifestyle.

Month of Meals

These menus were created by committees of the Council on Nutritional Science and Metabolism of the American Diabetes Association, and staff of the American Diabetes Association National Service Center in response to frequent requests for menus from people with diabetes and their families. The menus are designed to follow the exchange groups and provide 45-50% of energy from CHO, 20% protein, and about 30% fat. The menus provide 1200 or 1800 calories, and instructions are provided on how to adjust caloric levels upward or downward. Each menu provides 28 days of breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks with a different focus to help make planning meals easier.

Exchange List Approach

The Exchange Lists for Meal Planning were developed by the American Diabetes Association and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and have been in existence since 1950. The latest version of Choose Your Foods: Food Lists for Diabetes was released in 2019. The concept for this list is that foods are grouped according to similar nutritional value, and can be exchanged or substituted in the portion size listed within the same group. The exchange lists include:

- Carbohydrate group – includes starches, fruit, milk and vegetable.

- Meat and Meat Substitutes group – four meat categories based on the amount of fat they contain.

- Fat group – contains three categories of fats based on the major source of fat contained: saturated, polyunsaturated or monounsaturated.

The exchange lists also give information on fiber and sodium content. They can be utilized for people with type 1 or 2 diabetes. The emphasis for type 1 is on consistency of timing and amount of food eaten, while for type 2, the focus is on controlling the caloric values of food consumed. Use of the exchange list may be helpful for some people while others may benefit by learning from other carbohydrate counting resources available online and through numerous publications and resources.

Calorie Counting

These are meal planning methods that can be useful for people with type 2 diabetes who want to lose weight. Knowledge regarding the number of total calories in a given food (including pre-prepared and fast foods) and becoming adept at label reading, can help promote weight loss when incorporated into other lifestyle changes. One of the first studies designed to determine empirically if people can learn a calorie counting system and if estimated food intake improves with training demonstrated that use of the Health Management Resources Calorie System tool (HMRe, Boston, MA, USA) helped to teach people how to estimate food intake more accurately (77).

RESOURCES FOR DIABETES NUTRITION EDUCATION

Table 3.

DIABETES NUTRITION EDUCATION RESOURCES

| Choose My Plate | www.choosemyplate.gov |

|---|---|

| Eat Out, Eat Well | Your go-to resource for assembling healthy meals in just about any type of restaurant, from fast food to upscale dining and ethnic cuisines. Order from: The American Diabetes Assn., www |

| American Diabetes Associate: Standards of Care | Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of Care in Diabetes. 2024 https://doi |

| DNSG European Dietary Guidelines | The Diabetes Nutrition Study Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2023 https://doi.org/10 |

| What Can I Eat? The Diabetes Guide to Healthy Food Choices 2nd Edition | A 28-page guide for planning meals and making the best food choices. Includes carb counting, glycemic index, plate method, eating out, meals/snack ideas, best food choices and more. Order from: The American Diabetes Assn., Inc. www |

| Eating Healthy with Diabetes, 5th Edition | Picture cues for portion sizes and color codes for food types teach how to put together a healthy diet plan to manage diabetes Order from: The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. www |

| Diabetes Meal Planning Made Easy & Healthy Portions Meal Measure | Meet your health and nutrition goals with healthy diabetes meal plans, shopping strategies and our handy portion control guide. Order from: The American Diabetes Association, www |

| Diabetes Place Mat Kit for People with Diabetes | Order from: NCES Health & Nutrition Information Catalog- Available in Spanish https://www School Health Corporation https://www |

| The Complete Month of Meals Collection, 2017 | Available from: Amazon.com or American Diabetes Association, 1-800-232-6455; www |

| Choose Your Foods: Food Lists for Diabetes | Order from: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics OR American Diabetes Associations; www |

| Diabetes Food Hub | www.diabetesfoodhub.org. A website available on the American Diabetes Association site that has meal planning, grocery lists, recipes, menus and healthy substitutions. Section in Spanish available. |

| The Complete Guide to Carb Counting | American Diabetes Association 4th edition. Has all the expert information you need to practice carb counting, whether you’re learning the basics or trying to master more advanced techniques. Order from American Diabetes Association, http://shopdiabetes |

| Diabetes and Carb Counting for Dummies 1st Edition | By Sherri Shafer, RD, CDE. Provides essential information on how to strike a balance between carb intake, exercise, and diabetes medications while making healthy food choices. Available at Amazon.com |

The resources listed above are a sampling of the many available, primarily from the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Diabetes Association. There are several other organizations and websites which have educational materials available:

- Diabetes Care and Education (www.dce.org/public-resources/diabetes).

- Joslin Diabetes Center (www.joslin.org).

- National Diabetes Education Program (www.ndep.nih.gov; www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov)

REFERENCES

- 1.

- American Diabetes Association. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Supplement 1):S77-S110. [PMC free article: PMC10725816] [PubMed: 38078584]

- 2.

- Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Trends in Diabetes Treatment and Control in U.S Adults, 1999-2018. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(23):2219-2228. [PMC free article: PMC8385648] [PubMed: 34107181]

- 3.