All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: tni.ohw@sredrokoob). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: tni.ohw@snoissimrep).

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: 2010 Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: 2010 Revision.

Show details16.1. Recommendations

- Where available, use viral load (VL) to confirm treatment failure.(Strong recommendation, low quality of evidence)

- Where routinely available, use VL every 6 months to detect viral replication.(Conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence)

- A persistent VL of >5000 copies/ml confirms treatment failure.(Conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence)

- When VL is not available, use immunological criteria to confirm clinical failure.(Strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence)

In making these recommendations, the panel was concerned by the limitations of clinical and immunological monitoring for diagnosing treatment failure, and placed high value on avoiding premature or unnecessary switching to expensive second-line ART. The panel also valued the need to optimize the use of virological monitoring and ensure adherence.

16.2. Evidence

A systematic review was conducted to assess different strategies for determining when to switch antiretroviral therapy regimens for first-line treatment failure among PLHIV in low-resource settings. Standard Cochrane systematic review methodology was employed. Outcomes of interest in order of priority were mortality, morbidity, viral load response, CD4 response and the development of antiretroviral resistance.

16.3. Summary of findings

Based on the pooled analysis of the side-effects from two randomized trials (Home-based AIDS care [HBAC] and Development of antiretroviral therapy in Africa [DART]), clinical monitoring alone (compared to combined immunological and clinical monitoring or to combined virological, immunological and clinical monitoring) resulted in increases in mortality, disease progression and unnecessary switches, but there were no differences in serious adverse events.(148,149) However, in the HBAC trial, combined immunological and clinical monitoring was compared to combined virological, immunological and clinical monitoring, and there were no differences in mortality, disease progression, unnecessary switches or virological treatment failures.(148)

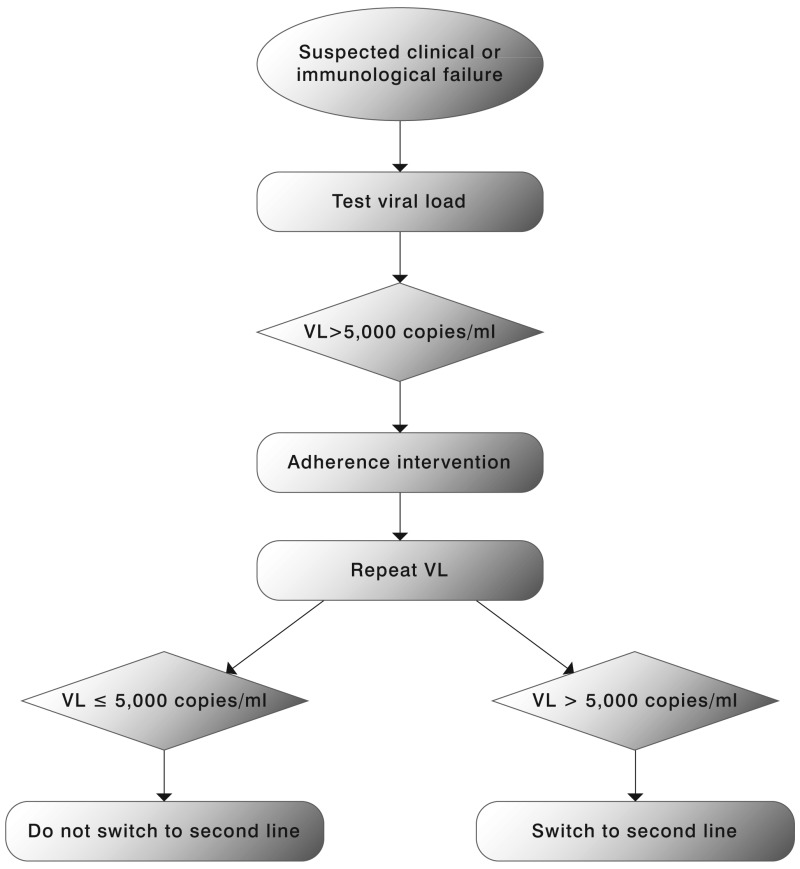

Viral load measurement is considered a more sensitive indicator of treatment failure compared to clinical or immunological indicators. VL may be used in a targeted or routine strategy. The objective of the targeted strategy is to confirm suspected clinical or immunological failure, maximizing the clinical benefits of first-line therapy and reducing unnecessary switching to second-line therapy. Targeted VL may also be used earlier in the course of ART (within 4 to 6 months of ART initiation) to assess adherence and introduce an adherence intervention in at-risk patients before viral mutations start to accumulate.(150)

The objective of the routine VL strategy is to detect virological failure early, leading to adherence interventions or changes in therapy that will limit ongoing viral replications, reduce the risk of accumulation of resistance mutations and protect the drug susceptibility of second-line and subsequent therapies.

While staying on a failing first-line therapy is associated with an increased mortality risk,(151) it is uncertain if VL monitoring, compared to clinical or immunological monitoring, affects critical outcomes. Immunological criteria appear to be more appropriate for ruling out than for ruling in virological failure.(152) Mathematical modelling that compared these three ART monitoring strategies did not find significantly different outcomes.(153) The use of virological monitoring strategies has been associated with earlier and more frequent switching to second-line regimens than the use of clinical/immunological monitoring strategies. However, data from ART programmes and global procurement systems also suggests that treatment switching has occurred at lower than expected rates in resource-limited settings. Low access to second-line drugs, difficulties in defining treatment failure and the limited availability of virological monitoring have been identified as important reasons for late switching. There is evidence to support a VL threshold of 5000–10 000 copies/ml to define failure in an adherent patient with no other reasons for an elevated VL (e.g. drug-drug interactions, poor absorption, intercurrent illness): this range of values is associated with higher rates of clinical progression and immunological deterioration in some cohort studies.(154,155)

Immunological failure is not a good predictor of virological failure. Depending on the study, 8% to 40% of individuals who present with evidence of immunological failure have virological suppression and risk being unnecessarily switched to second-line ART.(156)

While no consensus on ART monitoring and the diagnosis of failure was reached, the panel supported moves to reduce reliance on clinical failure definitions, expand the use immunological criteria and use viral load testing for confirmation of clinical/immunological failure in deciding when to switch to second-line therapy.

16.4. Benefits and risks

Benefits

More accurate assessment of treatment failure will reduce the delay in switching to second-line drugs. Targeted use of VL can limit unnecessary switching and routine use of VL can reduce the risk of resistance. While expensive, VL has the potential to save the cost of expensive second-line drugs by confirming that they are needed.

Risks

The optimum threshold for defining VL failure in a public health approach is still unknown, and there are limited data on the diagnostic accuracy of VL in resource-limited settings. There is a risk that resources used to expand laboratory capacity or conduct VL testing would divert funds away from expanding access to treatment.

Acceptability and feasibility

ART switching has occurred at lower than expected rates in resource-limited settings, and the limited use of virological monitoring has been identified as an important factor. Many countries are considering employing VL to optimize the use of expensive second-line drugs. The same rationale applies when third-line drugs are available. Physicians and PLHIV consider clinical and immunological monitoring insufficient to promote a timely switch and want VL monitoring. The initial and ongoing cost is high. The use of VL to confirm clinical-immunological switch (targeted approach) will cost less than the routine use of VL monitoring. Quality assurance programmes should be implemented at VL facilities irrespective of the VL strategy adopted. Central VL facilities with adequate specimen transportation from clinic to laboratory are feasible, as is point-of-care VL capacity in urban settings. Point-of-care VL capacity in rural settings is likely to remain unfeasible with current technologies. Feasibility was not systematically assessed, but targeted use of VL seemed more feasible to the panel than routine use.

16.5. Clinical considerations

One of the critical decisions in ART management is when to switch from one regimen to another for treatment failure. The 2006 recommendations on Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents recognized that definitions for treatment failure were not standardized and outlined a set of definitions for ART failure based on available evidence at that time. These remain basically unchanged except that the VL threshold for failure has changed from 10 000 copies/ml in 2006 recommendations to 5000 copies/ml in the current guidelines. An individual must be taking ART for at least 6 months before it can be determined that a regimen has failed.

Table 12ART switching criteria

| Failure | Definition | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical failure | New or recurrent WHO stage 4 condition | Condition must be differentiated from immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) Certain WHO clinical stage 3 conditions (e.g. pulmonary TB, severe bacterial infections), may be an indication of treatment failure |

| Immunological failure | Fall of CD4 count to baseline (or below) OR 50% fall from on-treatment peak value OR Persistent CD4 levels below 100 cells/mm3 | Without concomitant infection to cause transient CD4 cell decrease |

| Virological failure | Plasma viral load above 5000 copies/ml | The optimal viral load threshold for defining virological failure has not been determined. Values of >5 000 copies/ml are associated with clinical progression and a decline in the CD4 cell count |

- WHEN TO SWITCH ART - Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adol...WHEN TO SWITCH ART - Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...