Hereditary coproporphyria (HCP) is classified as both an acute and a chronic porphyria. Porphyrias with neurologic manifestations are considered acute, because the symptoms occur as discrete, severe episodes. Porphyrias with cutaneous manifestations are considered chronic, because photosensitivity is long standing (see Table 3).

In a German study of 46 individuals with acute HCP, 90% had abdominal pain; only 13% had cutaneous findings despite substantial overproduction of coproporphyrin [Kühnel et al 2000]. An earlier British study of 111 individuals with HCP reported similar findings [Brodie et al 1977].

Acute Attacks

The initial symptoms of an acute attack are nonspecific, consisting of low-grade abdominal pain that slowly increases over a period of days (not hours) with nausea progressing to vomiting of all oral intake.

Typically the pain is not well localized but in some instances does mimic acute inflammation of the gallbladder, appendix, or other intra-abdominal organ. In most instances the abdominal examination is unremarkable except for diminished bowel sounds consistent with ileus, which is common and can be seen on abdominal radiography. Typically fever is absent. In a young woman of reproductive age, the symptoms may raise the question of early pregnancy.

Prior to the widespread use of abdominal imaging in the emergency room setting, some individuals with abdominal pain and undiagnosed acute porphyria underwent urgent exploratory surgery. Thus, a history of abdominal surgery with negative findings was considered characteristic of acute porphyria.

A minority of affected individuals has predominantly back or extremity pain, which is usually deep and aching, not localized to joints or muscle groups.

Neurologic manifestations. Seizures may occur early in an attack and be the problem that brings the affected individual to medical attention. In a young woman with abdominal pain and new-onset seizures, it is critical to consider acute porphyria because of the implications for seizure management (see Management).

When an attack is unrecognized as such or treated with inappropriate medications, it may progress to a motor neuropathy, which typically occurs many days to a few weeks after the onset of symptoms. The neuropathy first appears as weakness proximally in the arms and legs, then progresses distally to involve the hands and feet. Neurosensory function remains largely intact.

In some individuals the motor neuropathy eventually involves nerves serving the diaphragm and muscles of respiration. Ventilator support may be needed.

Tachycardia and bowel dysmotility (manifest as constipation) are common in acute attacks and believed to represent involvement of the autonomic nervous system.

Of note, when the acute attack is recognized early and treated appropriately (see Management), the outlook for survival and eventual complete recovery is good. Individuals with frequent recurrent acute attacks (defined as more than four attacks per year) have historically been at highest risk for development of chronic neurologic manifestations. In November 2019, givosiran, an siRNA that works directly against ALAS1, was approved in the US after demonstrating effectiveness in preventing acute attacks in these individuals. Effective prevention of acute attacks with givosiran may reduce or prevent the development of neurologic sequelae in persons with HCP with frequent recurrent attacks, though this remains to be determined with long-term study (see Treatment with Givosiran).

Psychosis. The mental status of people presenting with an acute attack of porphyria varies widely and can include psychosis. Commonly the predominant feature is distress (including pain) that may seem hysterical or feigned, given a negative examination, absence of fever, and abdominal imaging showing some ileus only. Incessant demands for relief may be interpreted as drug-seeking behavior.

Because of the altered affect in acute porphyria, it has been speculated that mental illness is a long-term consequence of an attack and that mental institutions may house disproportionately large numbers of individuals with undiagnosed acute porphyria. Screening of residents in mental health facilities by urinary porphobilinogen (PBG) and/or PBG deaminase activity in blood (which diagnoses acute intermittent porphyria) has been performed, with mixed results [Jara-Prado et al 2000]. The experience of those who have monitored affected individuals over many years suggests that heterozygotes who are at risk for one of the acute porphyrias are no more prone to chronic mental illness than individuals in the general population; however, a prospective study is needed.

Kidney and liver disease. In people with any type of acute porphyria, the kidneys and liver may develop chronic changes that often are subclinical. One manifestation of the liver problem is excess primary liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma). The risk is greatest in women older than age 60 with acute intermittent porphyria (160-fold increased risk above the general population risk); for men there is a 37-fold increase in risk [Sardh et al 2013]. This and the kidney disease may be restricted largely to heterozygotes with chronically elevated plasma or urine delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Hypertension may be chronic in those with frequent symptoms and may contribute to renal disease.

Inasmuch as ALA and PBG tend to be minimally elevated or normal in HCP heterozygotes, the risk of hepatic and renal complications may be less in HCP than in acute intermittent porphyria.

Circumstances commonly associated with acute attacks are caloric deprivation, changes in female reproductive hormones, and use of porphyria-inducing medications or drugs:

Chronic (cutaneous) manifestations. Photocutaneous damage is present in only a small minority of those with acute attacks. Bullae and fragility of light-exposed skin, in particular the backs of the hands, result in depigmented scars. Facial skin damage also occurs, with excess hair growth on the temples, ears, and cheeks; this is more noticeable in women than in men.

The cutaneous findings in HCP resemble those in porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and in variegate porphyria (VP).

Threshold for a Pathogenic Effect of Porphyrins and Their Precursors

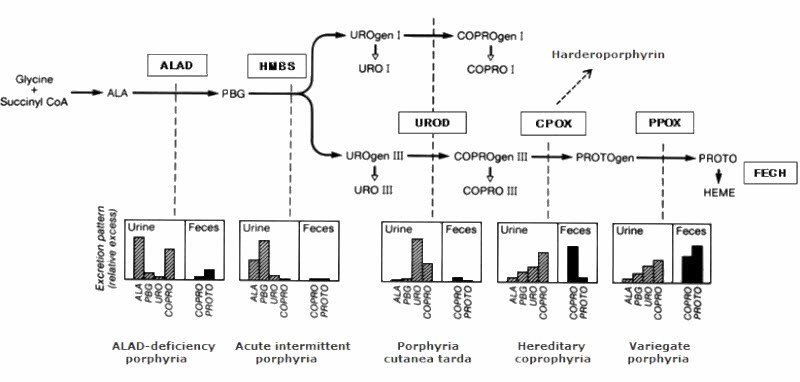

Clinically active acute porphyria is associated with substantial elevation of the precursors ALA and PBG in the blood and urine; the cutaneous porphyrias are associated with increased porphyrins in blood, urine, and feces. In the acute porphyrias and cutaneous porphyrias, a threshold for symptoms appears to exist.

Acute (hepatic) porphyrias. A threshold for acute attacks is suggested by the fact that in virtually all symptomatic individuals, urinary PBG excretion exceeds 25 mg/g creatinine, or more than tenfold the upper limit of normal. Urinary ALA excretion increases roughly in parallel.

In contrast, in asymptomatic individuals the baseline urinary PBG excretion varies widely, usually low or normal but occasionally exceeding 25 mg/g creatinine. For this reason, it is advisable to establish the baseline urinary PBG excretion for

CPOX heterozygotes (see Management,

Evaluations Following Initial Diagnosis).

Chronic (cutaneous) porphyrias. A threshold has been well defined for porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), in which photosensitivity occurs at values of urine uroporphyrin (the predominant pathway intermediate) that are more than 20-fold the upper limit of normal. However, the same is not apparent with regard to urine coproporphyrin: only a minority of CPOX heterozygotes exhibit any photosensitivity.

Of note, in individuals with HCP and chronic liver disease the cutaneous component may be more prominent than expected for the observed urine or plasma PBG concentration. Coproporphyrin leaves the plasma largely via the liver going into bile. In chronic liver disease, bile transport processes or bile formation may be impaired, leading to accumulation of coproporphyrin in plasma, which then results in photosensitivity.