NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

This document presents the work conducted by the group of experts brought together by Inserm within the scope of the collective expert report procedure (Appendix) in response to the request expressed by the Direction générale de la santé about public health’s questions related to gambling. This work is based on the scientific data available during the first quarter of 2008. Almost 1,250 articles have served as the documentary basis for this expert report.

This collective expert report has been coordinated by the Inserm Collective Expert Report Center.

Group of experts and authors

Jean ADES, Service de psychiatrie, Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes

Elisabeth BELMAS, Histoire moderne, Université Paris XIII, Maison des sciences de l’Homme, Paris-Nord

Jean-Michel COSTES, Observatoire français des drogues et des toxicomanies (OFDT), Saint-Denis

Sylvie CRAIPEAU, Sociologie, Institut national des télécommunications, Évry

Christophe LANÇON, Service de psychiatrie adulte, CHU Sainte-Marguerite, Marseille

Michel LE MOAL, Neurogenèse et physiopathologie, unité Inserm 862, Neurocentre Magendie, Bordeaux

Jean-Pierre MARTIGNONI, Groupe de recherche sur la socialisation, Faculté d’anthropologie et de sociologie, Université Lumière-Lyon 2, Bron

Sophie MASSIN, Économie de la santé publique, Université du Panthéon-Sorbonne (Paris I), Paris

Jean-Pol TASSIN, Collège de France, Génétique moléculaire, neurophysiologie et comportement, unité Inserm UMR 7148, Paris

Marc VALLEUR, Psychiatrie, Hôpital Marmottan, Centre de soins et d’accompagnement des pratiques addictives, Paris

Martial VAN DER LINDEN, Unité de psychopathologie et neuropsychologie cognitive, Faculté de psychologie et des sciences de l’éducation, Université de Genève, Genève, Suisse

Jean-Luc VENISSE, Centre de référence sur le jeu excessif, Pôle universitaire d’addictologie et psychiatrie, CHU Nantes, Nantes

Critical rereading

Michel LEJOYEUX, Unité fonctionnelle de psychiatrie d’urgences adultes, tabacologie, alcoologie, Hôpital Bichat-Claude-Bernard, Paris

The following presented papers

Christian BUCHER, Psychiatre des Hôpitaux, CH de Jury, Metz

Colas DUFLO, Philosophie, Université de Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens

Alain EHRENBERG, Centre de recherche psychotropes, santé mentale, société (CESAMES), UMR 8136 CNRS, unité Inserm 611, Université René Descartes-Paris 5, Paris

Robert LADOUCEUR, École de psychologie, Université Laval, Québec, Canada

Etienne MARIQUE, Président de la commission des jeux de hasard, Bruxelles, Belgique

Gilles PAGES, Laboratoire de probabilités et modèles aléatoires, UMR-CNRS 7599, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris

Olivier SIMON, Centre du jeu excessif, Section d’addictologie, Service de psychiatrie communautaire, Département de psychiatrie du CHUV, Lausanne

Serge TISSERON, Laboratoire de psychopathologie des atteintes somatiques et identitaires, Université Paris X, Nanterre

Scientific, editorial, bibliographical and logistic coordination

Elisabeth ALIMI, chargée d’expertise, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Fabienne BONNIN, attachée scientifique, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Catherine CHENU, attachée scientifique, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Jeanne ETIEMBLE, directrice, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Cécile GOMIS, secrétaire, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Anne-Laure PELLIER, attachée scientifique, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Chantal RONDET-GRELLIER, documentaliste, Centre d’expertise collective de l’Inserm, Faculté de médecine Xavier-Bichat, Paris

Foreword

The gambling industry is an important economic and financial sector, which produces employment (direct and indirect) and taxation revenue, and involves a gamblers population of millions of people. According to Insee in 2006, almost 30 million people in France, or three out of five people of gambling age, gamble at least once per year. Since 1975, the total value of stakes has doubled. According to the Trucy report, the turnover of the legitimate gambling industry has increased from the equivalent of 98 million euros in 1960 to 37 billion in 2006.

Gambling is social and cultural practices which have a very long history in leisure activities. They now occupy an important place in everyday life, both in free time and at special events. Whereas gambling is a recreational activity for a large number of people, they can be harmful for some, with individual, family and social-occupational consequences. For some gamblers, gambling can take on the features of addictive behavior.

The possible dangers of gambling are increasingly drawing the attention of public bodies and gambling operators themselves. A request made to Inserm by the Directorate General for Health for a collective expert report was motivated by the need to provide assistance, support and care for people with gambling difficulties.

In order to respond to this request, Inserm brought together a multi-disciplinary group of experts in history, sociology, health economics, epidemiology, psychology, neurobiology, psychiatry and addiction medicine. This group organized its thinking on gambling and video and Internet games using several approaches: historical, sociological, psychological, neurophysiological and clinical as well as a public health approach. The way in which gambling problems are handled in some countries was an additional area considered.

In the course of ten working group meetings, the group of experts analyzed approximately 1,250 articles containing the available national, European and international data on gambling, its context, gambling behavior and addiction. In the expert report, the group uses the terms “problem gambling” and “pathological gambling”1 as used in most studies to designate problematic gambling practices.

The group of experts consulted several reports and interviewed 8 people dealing with these problems. Following a critical analysis of the literature it has produced an overview and proposed a number of recommendations for action and research.

Footnotes

- 1

The pathological player meets the criteria for a clinical diagnosis. The problem player has difficulties with gaming behaviour without meeting all of the criteria for pathological gambling.

Summary

Gambling has continuously developed in different forms in Western societies for the past 300 years. Gambling activities were initially prohibited in France by Royal Decree and for a long time were conducted in secret. They were legalized in the last third of the 18th century with the creation of the royal lottery. The principles defined for gambling at the time live on today.

In gambling, the person irreversibly hands over a good (money or object) and the end of the game results in a loss or gain determined partially or totally by chance. For a long time gambling has had a social and economic dimension. In the current social context (easy borrowing, consumer society and the huge increase in the number of games available), the various forms of compulsive expenditure (gambling purchases) can represent an ”unlucky encounter” between a vulnerable person with unmet desires and an attractive marketing offer giving the illusion of fulfilling a “missing need”.

Excessive gambling appears to be the product of personal history and a global social, economic, historical and cultural context. Although a public health problem, its causes and consequences are fundamentally social and as such it is an indicator of our society. Whilst the expert report draws widely on psychological and medical work to analyze pathological gambling, the social, economic and cultural causes liable to explain excessive gambling should in no way be overlooked.

The sociological approach to gambling considers that the degree of “closeness” between the gambler and his/her gambling depends on the relationship that the gambler establishes with the game in a given social and personal context.

Although the existence of pathological gamblers was described as early as 1929, the concept of pathological gambling appeared in the scientific literature around the end of the 1980s. Excessive gambling was firstly considered to be a manifestation of compulsive disorders, following which the disorder was then gradually included in the group of “non-substance additions”. It was at this time that it was suggested that the best method to study addictive disorders was not to examine each as an isolated entity but rather to “search for a common origin or mechanism for addictions which are expressed through a multitude of behavioral expressions”. From an analysis of the international scientific literature on “pathological gambling”, different models are now proposed obtained from the psychoanalytical, psychological and psychobiological fields to explain researchers’ working hypotheses on gambling addiction. These different models incorporate multiple interactions between individual and environmental factors. Like substance addition, gambling addiction can occur as a result of a meeting between a product, a personality and a social-cultural moment. The recent emergence of video and Internet games opens new avenues for research into the problem of addiction.

Identification of the different risk and vulnerability factors for pathological gambling, and improved knowledge about the trajectories of the gamblers who become involved in pathological and risk gambling practices at a given time, are key objectives for constructing preventive actions, facilitating access to care and also defining the most relevant indications for treatment.

A few details on the history of gambling

Four major debates characterize the history of gambling in France.

The moralist and clerical debate, which is very old, is hostile to gambling for theological and moral reasons: the use of chance for profane and entertainment purposes is an outrage to divine Providence, which should only be used in extreme situations. This intransigent position changed at the end of the 17th – early 18th century, when under the influence of probability mathematics, the idea that chance is indifferent “per se” established itself with clerics and lay people. The secular moralist debate extended into the second half of the 18th century with Enlightenment thinkers who then centered their attacks on the pernicious social consequences of gambling and on the policy followed by the monarchy which stood accused of having created the French Royal Lottery in 1776, thereby promoting the ruin of families. It should be noted however that as of 1566, the Royal State strove to limit the social effects of gambling by limiting and then canceling gambling debts. The moralist debate which considered compulsive gambling firstly to be a sin (16th –17th century) and then a vice (18th century) still influenced the views of philosophers such as Roger Caillois (1958) on gambling in the 20th century.

A literary debate around gambling, which was strongly influenced by the moralist view, appeared at the end of the 17th century. Through plays and novels acted or published since approximately 1670 the tragic figure of the gambler led into misery, ruin and death by his passion took form. This representation continued into the 19th and 20th centuries with the novels of Dostoïevsky, Stefan Zweig and Sacha Guitry.

A philosophical and anthropological debate which was very fertile in the 20th century developed in Kant’s and Schiller’s analyses. This debate, which was successively illustrated by J. Huizinga, M. Klein, DW. Winnicott, J. Château, R. Caillois, J. Henriot, LJ. Calvet, JM. Lhôte and C. Duflo, reasserted the value of gambling and gaming in general. Gaming activities were then seen as an entirely separate activity, free, regulated, limited in time and space and providing both joy and excitement to humans (J. Huizinga), a form of behavior and a social reality (J. Château, R. Caillois), a contract based on “legaliberty” (C. Duflo).

The historical debate is represented on one side by academic works listing and describing past games and, on the other, by work replacing gaming in a global social context. This latter category of work deals extensively with gambling, studied in the Middle Ages and in the modern era. Their authors have found a description of players’ behavior, which would now be described as excessive, in ancient texts. Belonging to the social elites of their time (Court, aristocracy, army) they conformed to the “ethos” of their social group, which valued extravagance and risk-taking. Their attitude is similar to the “potlatch” rituals described by J. Huizinga (1951) or “ordalic” behavior described by M. Valleur (1997). It was probably in the 18th century with the spread and “democratization” of lotteries-particularly with the creation of the royal lottery in France in 1776 – that the general population was more exposed to the risks of excessive gambling. This is borne out in the criticisms formulated by the philosophers and the terms of Royal legislation.

There are very few serious historical works on gambling in the 19th and 20th centuries in France because of access restrictions to archives held by gambling operators and the legal consultation periods.

Access to archives is less restrictive in North America which has promoted research into the recent history of gambling. Approximately 80% of adults in the United States gamble at least once during the year. The risks of gambling have been denounced since 1957 by “Gamblers Anonymous”, which in 1970 joined the National Council on Compulsive Gambling alongside representatives of the medical profession, clergy and lawyers’ associations. It was in 1980 that excessive gambling became included in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Diseases” (DSM) produced by the American Association for Psychiatry. In some peoples’ opinion this “medicalization” of excessive gambling could lead to an underestimation of the political, social and familial explanatory factors which could play a key role. The State, which is the principal manager of the various gambling places and also protector of its citizens is therefore faced with a complex social dilemma which hinders the introduction of an effective prevention policy that is socially acceptable and ethically legitimate.

Identical historical changes have been seen in Canada, where moral, social, political, medical and economic arguments have been put forward both to censor and legitimize gambling. As long as gambling was strictly controlled, regulated and in some cases originated from the government, Canadians accepted it as part of a policy contributing to public good because of its economic benefits. This position was questioned following the large rise in gambling and the damage caused by video lottery terminals (VLTs) and slot machines. In this context, the joint action of senior governmental officials and the gambling industry, backed by experts and professionals, contributed to the birth of the concept of “responsible gambling” and to the development of prevention and warning programs for high-risk populations. In some peoples’ view the concept of “responsible gambling” has transformed the social problems associated with excessive gambling into individual problems, thereby removing their political nature.

What is the current situation of gambling in France?

It was in the 20th century that casinos, the PMU (Pari mutuel urbain created in 1931) and the National Lottery (reestablished in 1933) developed in France. These are the three gambling operators that currently still operate in France, and whose major beneficiary is the State.

There are 192 casinos in France with a total turnover of 18.66 billion in 2004 and 64 million admissions. Most French casinos are owned by 5 private investment groups under State control (Ministries of the Interior and Finance) and local authorities.

PMU administers betting outside of the racetracks. The Tiercé, created in 1954, was followed by an increase in the number of races and the diversification of betting (Quarté, Quinté). The turnover of the PMU was estimated to be 8 billion euros in 2006. There were 8,881 PMU sales outlets in 2005. Racetrack bets only represent 4% of racing bets in France. The ways of betting have become more diversified in recent years with interactive television (Equidia channel created in 1999), Internet betting (since 2003) and mobile phone betting (since 2006). The total number of people betting was 6.8 million in 2005.

Française des jeux (FDJ) administers the Lotto, the successor to the National Lottery in 1980, the Sports Lotto, Keno and scratch card gambling. This is a semi-public company in which the State holds more than 70% of the shares. It had a turnover of 9.7 billion euros in 2007. In 2005 there were approximately 40,000 sales outlets and it is also possible to bet on the Internet. Five million people play the Lotto each week.

Gambling has increased considerably over the last 40 years. The turnover of the authorized gambling industry in France has increased from 98 million euros in 1960 to 37 billion euros in 2006, with an acceleration over recent years. In the space of 7 years (1999-2006), bets placed by gamblers have increased by 77% for Française des jeux, 91% for PMU-PMH2 and 75% for the casinos.

The launch of many new gambling (notably Lotto, Scratch card gambling, Rapido and Euro millions for Française des Jeux, Tiercé, Quarté, Quinté+ and many other forms for the PMU), the legalizing of slot machines in casinos and more recently of poker, the increased number of gambling places (often very close together in the case of FDJ and PMU), computerized processing, the gaming network across the country as well as the intense media coverage and permanent commercial communication for these products (televised draws, advertising, sponsoring, etc.) partly explain the success and popularity of gambling. It now plays a major role in leisure activities in France. In addition, and although they fall outside of the national statistics by definition, illegal gambling and above all the large number of illegal on-line gambling sites with future growth prospects reinforce the phenomenon.

Gambling and its peripheral related activities are economically and financially significant (more than 100,000 people directly employed) and contribute to the development of many economic, cultural and commercial sectors (particularly horse-riding for PMU, animation and the cultural life of spas for casinos, sport for FDJ and so on). This sector contributes significantly to State finances (6 billion euros) and to those of 200 districts. It redistributes money to thousands of winning gamblers and also to different organizations, bodies and associations.

Regulations, legislation and the different control and legal authorities (administrative, fiscal and police) set up by public bodies have guaranteed the equity and safety of gambling, while protecting public order in general. The dual role played by the State in this specific economic, social and cultural activity has provided protection, but also growth. How can the resulting conflict of interest which has been present for a long time now be taken into account in the policy of responsible gambling desired by the public bodies and all of those involved in the gambling sector, but also in the context of modernizing the gaming and gambling sector, virtual or not, desired by the European Union (EU)?

Who gambles in France?

Forty-one per cent of usual casino attendees are either non-working individuals or retirees. Those over 50 years old or under 30 years old each make up approximately 30% of slot machine gamblers, 57% of whom are men.

Of the 6 million PMU betters, 65% are men between 35 and 49 years old, generally from modest social-occupational backgrounds. Of these, 55% are regular clients who play above all at the weekend, 40% are occasional gamblers drawn by large racing events and 5% are dedicated gamblers who play several times each week.

In 2006, 29 million people played a Française des Jeux gambling; 49% of these were men, 51% were women and 34% were under 35 years old. The gamblers have almost the same social-occupational profile as the general population, with a slight over-representation of laborers and salaried employees. There are slightly more young people and slightly fewer elderly persons amongst the gamblers than in the general population3.

Gamblers’ bets and their net expenditure (their losses minus their gains) have increased considerably in recent years. The turnovers of gambling operators have also increased over the same years. In 2005 gamblers’ returns represented approximately 60% of turnover for FDJ, more than 70% for PMU and 85% for the casinos. According to the report by Senator François Trucy (2006), expenditure on gambling is estimated to be 134 euros per person per year.

Change in bets and net annual expenditure of gamblers with the three operators (from the Trucy Report, 2006)

| Year | FDJ | PMU | Casinos | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bets (euros) | Net expenditure (euros) | Bets (euros) | Net expenditure (euros) | Bets (euros) | Net expenditure (euros) | |

| 1999 | 175.35 | 74.16 | 656.09 | 202.37 | 1 776.80 | 213.55 |

| 2005 | 309.65 | 123.88 | 1 251.27 | 341.59 | 3 108.86 | 435.24 |

Development of video and Internet games

What is known as video gaming is a recent phenomenon which emerged in the 1970s; it became much more widespread and was transformed by the Internet in the 1990s.

The two countries that create video games are the United States and Japan. The first video game was produced in the 1950s. Space War was created in 1962 by a student from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The first Nintendo games console dates back to 1983.

The video games world incorporates three main themes: science fiction, role playing (notably “Dungeons and Dragons”) and simulation, i.e. a technical world (computer technology and simulation) and an imaginary universe and game. The novelty of these games is that they offer a potential space where players act within or even beyond their imagination.

Video games have now moved into a new market thanks to the Internet, resulting in new multiplayer games: massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) or massively multiplayer online games (MMOG). These games can last from 20 minutes to a year and are played against other players or against the machine and require the development of specific skills. The “World of Warcraft” game is a model of a successful general public MMORPG according to the manufacturers. This is the most widely played online game in the world with 9 million subscribers in 2007. The game involves 2 to 40 players who move throughout all of the continents in the world. Hundreds of hours are needed to reach a given level. Rewards can be obtained on entering the game for simple tasks, followed by promises of greater rewards for the more difficult tasks. As players are always on the point of gaining new skills they increase their playing time to achieve these new rewards.

“Second Life” is a 3D virtual universe brought out in 2003. It is a simulation space more than a game and enables the user to live a sort of “second life”. Most of the virtual world is created by the residents themselves who evolve through the avatars that they create. It is also an Internet forum in which debates, presentations, conferences, training and marriages take place. This universe is invested in heavily by organizations (companies, political parties, large schools, etc.) that use it as a window and a marketing media. It illustrates a certain blurring of the boundaries between the games world and the economic world, places for socialization and places for gathering information.

The introduction of video games and the Internet into social life is a recent phenomenon. These games have so far been very little studied, particularly in France.

According to a French survey in 2002, 80% of children between 8 and 14 years old reported that they played video games, 53% reporting that they play 2 hours or less per week and 26% that they spent more than 4 hours playing per week4.

This is the first time that this type of game, which is entirely new and due entirely to the extension of communication techniques, has appeared in our society. The young age of the people who play most is interpreted as a generational effect as video games require skills that come from an IT culture. This gaming behavior is also a means of socialization between peers and a means of seeking identity reassurance.

Both qualitative and quantitative work has revealed the predominantly male population in video gaming. They are also generally of a high social-cultural level, with an average age of 265. According to some authors, the male over-representation is explained by the fact that most of the games on offer relate more to male socialization (promoting aggression, violent games).

In terms of Internet use, Insee reported in 2006 that 34% of young Internet users (15 to 18 years old) used it to play games. A recent survey of sports bettors on the Internet showed that more than 91% of players were male, with an average age of 31.

Socio-economic impacts and damage associated with gambling

Most of the studies covered (United States, New Zealand, Australia, England, Sweden, Germany, etc.) have examined the socio-economic impacts of the liberalization and development of gambling, either on a community, town or national level. These studies mostly examine the “problematic” effect of the gambling business: increased impoverishment, excessive debt, suicide, family problems, gambling-related divorce, concomitant gambling and “substance” addiction (alcohol, drugs, etc.). Gambling would appear to cause more social problems in poorer populations, as the proportion of their expenditure on gambling is higher even though the amounts spent on gambling are lower. Gambling can also dismantle community and family relationships. In the worst-case scenario, this leads to inveterate gamblers losing everything in gambling and finding themselves with no resources.

The legalization of gambling has brought economic benefits and new jobs to the residents of Nevada but it also has social costs. According to Nevada residents, some people loose control of their gambling although at the same time the legalization of gambling has brought improved quality of life to their community. However, the perception of these advantages and disadvantages varies depending on the sub-populations studied (educational level, whether or not working in the gambling industry, etc.).

In Canada, a survey in a population of gamblers (managed by Joueurs Anonymes) showed that approximately 25 to 33% of jobs lost and personal bankruptcies were linked to gambling.

An exploratory study in France among people consulting the “SOS Joueurs” association showed that the majority of gamblers questioned had been faced with excessive debt, almost 20% had committed crimes (particularly breaches of trust, theft, check counterfeiting, etc.).

In terms of suicide and divorce rates, a survey conducted in eight regions in the United States between 1991 and 1994 did not find any significant difference between regions with a casino and control communities. Over a longer period however (1970-1990), a modest positive correlation was found between suicide rates and the presence of a casino in urban areas. This result was not seen in the analysis of suicide rates before-after the legalization of gambling.

Studies (particularly in the United States and Canada) differ in terms of the relationship between the presence of a casino in a region and an increase in the criminality rate.

Problem gambling in an Australian study was 20 times higher in prison inmates than in the general population. Another study examined suspects arrested in two American towns. Three to four times more problem gamblers were found in this study than in the general population.

Social cost of gambling

Calculating the social cost of gambling is designed to provide a quantitative estimate of the harmful economic and social consequences of gambling in a given geographical area at a given time. In order to have meaning it must be based on rigorous methodology. The classic economic approach based on the teachings of welfare economics, although not the only possible approach, emerges as one of the most robust provided that one is aware of its interest and limitations.

Until now the economics of gambling has not been greatly studied. The studies that specifically set out to calculate social costs are almost all Anglo-Saxon, predominantly concern casino gambling and contain a huge variety of approaches and results. The 1st international symposium on the economic and social impact of gambling (Whistler, Canada, September 2000) and then the 5th Alberta annual conference on gambling research (Banff, Canada, April 2006) attempted to put some order into this muddle of research approaches, although ultimately it was still impossible to reach a consensus on an analytical framework to study the economic consequences of gambling. Methodological controversies surround the definition of the objectives chosen (choice of perspective and counterfactual scenario), the determination of the costs to include in the analysis (questions about handling “transfers”, “internal costs”, “family costs”, costs related to the institutional organization of the country and “discretionary costs”) and methods used to measure these costs (identifying reliable data sources representative of the population, estimating costs attributable to gambling and allocating monetary values to intangible costs).

This lack of consensus is regrettable as adopting a common analytical framework, even if imperfect, would have many advantages, particularly improved legibility and greater comparability of the estimates produced. Four national studies conducted in the United States, Australia, Canada and Switzerland merit being quoted. The Australian study, which is the most complete, is usually used as the reference work. This study found the total social cost of problem gambling in 1997–1998 to lie within a range between 1.8 and 5.6 billion Australian dollars.

Whilst the total social cost of gambling is difficult to interpret as “raw data,” an analysis of its breakdown is however very instructive. Firstly, gambling costs are to a very large extent (90%) psychological costs generated by the small group of problem gamblers and borne by themselves and by their families and friends. A comparison with the social cost of drugs in Australia also shows that gambling incurs proportionally more intangible costs than legal and illegal drug abuse. Secondly, estimates of costs by type of gambling show major differences by category and reveals slot machines (and to a lesser extent betting) to be the greatest cost generators.

The Trucy report provides a good summary of the state of research in France on the social cost of gambling: “In France? Nothing on the subject, the same as for other areas of research on gambling. This is at the very least disappointing even if it is extremely difficult to do the calculations”. At present we therefore have no other choice than to base our work on estimates made in other countries, which we can try to assess by comparing them with estimates of the social cost of drugs in France. We observe that the estimated social cost of gambling in Australia (tangible costs only) is almost the same as the social cost of cannabis estimated in France (15 euros per person per year).

Comparison of the estimated social cost of gambling in Australia (1998) with the estimated social cost of drugs in Australia and in France (tangible costs only)

| Social cost per person in eurosa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | France | ||

| Activity | CTTb | CTAc | CTA |

| Smoking | 435d | 225d | 770f |

| Alcohol | 155d | 120d | 600f |

| Illegal drugs including cannabis | 60d | 45d | 45f |

| Gambling | 50–160 | 5–16e | |

- a

In euros, price of the year of study, current exchange rate;

- b

CTT: Total cost;

- c

CTA: Tangible costs only;

- d

Collins and Laspsley (1996), estimate for 1992;

- e

Productivity Commission (1999), estimate for 1997–1998;

- f

Kopp and Fenoglio (2006), estimate for 2003;

- g

Ben Lakhdar (2007), estimate for 2003

Some useful information can also be extracted from an analysis of social costs to help construct public policies. Firstly, the estimated sum provides theoretical justification for State intervention, and to this end comparison with other types of activity may help with priority setting. Next, it is also extremely valuable to define the desirable form of State intervention. As it emerges that a very large proportion of the social cost of gambling is due to so-called “internal” costs, i.e. costs which the minority of highly dependent gamblers impose on themselves, gambling emerges as an ideal area to apply the concept of “asymmetric paternalism”. This concept proposes to introduce policies specifically targeting the small group of problem gamblers (those who both create and bear the largest proportion of the cost) without penalizing others. The majority of non-dependent gamblers generates little or even no social costs and gain pleasure from gambling. If in addition we adopt the hypothesis of limited rationality associated with time-inconsistent dependent gamblers, it may be useful to promote self-control mechanisms (for example voluntary bans in casinos) that will allow the gamblers to not succumb to their short-run preferences and help them get out of their addiction. Finally, it is essential that public policies target as a priority the gambling that incur the greatest costs and adapt to the development of Internet gaming and gambling.

An analysis of the literature on the social cost of gambling reveals the extent of current debate and highlights the need for continued research. Since French people appear to be increasingly drawn to gambling, and the gambling supply is undergoing great change, it would be extremely useful to have indicators for France.

What motivates gamblers?

A number of sociological studies have examined the motivations for specific homogeneous populations. In people over 65 years old, relaxing and enjoying themselves, passing the time and combating boredom are the motivations most reported by gamblers. Other studies have analyzed for example the motivations in four ethnically different communities (North African, Chinese, Haitian, and Central American) in Montreal: in these communities the hope of making significant gains and improving their economic situation is an important motivation for gambling. The desire to come closer to the culture of the host country in order not to feel excluded is also a motivation for gambling even if its practice contradicts the traditional culture of origin (for example North Africa). Believing in chance and the supernatural is also a component of gambling for Chinese and Haitian cultures. Gambling is part of social and family life from the youngest years onwards in Central American countries.

Sociological studies have examined the behavior, rituals, movements, exchanges and conversation of gamblers. A detailed study of gamblers in the natural gambling situation is useful to understand the social and cultural perspective of contemporary gambling including in situations when it appears to be excessive from a commonsense perspective.

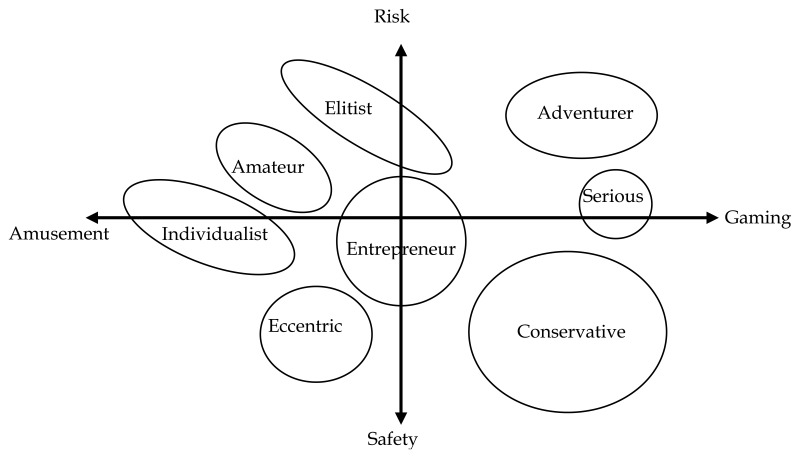

This qualitative research provides a clear view of the different “categories” of gamblers not only from a sociological perspective in terms of social features but also in terms of gambling practices. Some authors have proposed a typology for gamblers consisting of eight categories or psychobiological portraits each making up 8 to 21% of the population studied: individualist, eccentric, amateur, elitist, entrepreneur, adventurer, serious and conservative. Each of these profiles can be positioned along two axes: level of risk or safety and level of involvement in the act of gambling (amusement/gamble).

Biographical information, personal accounts and portrait are also used in the qualitative sociological studies. A “sociological conversation with a gambler” shows that the history of gambling in the problem gambler is part of the person’s life history and biography. This conversation also illustrates the ups and downs that some excessive gamblers battle with between “putting problem gambling at an aesthetic distance and the painful confrontation with reality”.

Psychoanalytic approaches to gambling

The most famous psychoanalytic text on gambling is still Freud’s “Dostoevsky and Parricide” (1928) which contains an essential part of the psychoanalytic considerations on gambling, which ”no one could regard … as anything but an unmistakable fit of pathological passion”.

According to Freud, this passion has the psychical function of self-punishing behavior: ”When Dostoevsky’s sense of guilt was satisfied by the punishments he had inflicted upon himself, his inhibitions against work disappeared, and he allowed himself to take a few steps along the road to success.“ Parricide, which haunts the writer’s work, is the keystone of his masochistic conduct.

This text puts forward, as a profound mechanism of the pathological gambler’s conduct, the problematic issue of the integration of the Law, to the extent that the father’s murder, and the mechanisms of its repression or overcoming, lie at the base of the constitution of moral structures for the individual, as well as being, for humanity, a condition of the integration of the individual as a member of the human community, as a member of civilization.

Freud expressly connotes the gambling passion with a pathological dimension. Thus, gambling, a ruinous ”pathological passion”, assumes the value of “self-punishment” behavior correlative to the wish to ”put the father to death”.

According to Bergler (1936 Bergler (1957), like in the case of Dostoevsky, gamblers practice ”gambling for gambling’s sake” and for the mysterious thrill, the ineffable sensation reserved to initiates. The gambler is to be considered as a neurotic, driven by the unconscious desire to lose, in other words by moral masochism, the unconscious need for self-punishment. As an expression of a ”base neurosis” corresponding to an oral regression, gambling would be the implementation of a sequence that is always identical, representing an illusory attempt to purely and simply eliminate the disagreeable side of the reality principle, in favor of the pleasure principle alone.

This operation requires a return to the fiction of infantile all-powerfulness, and the rebellion against parental law, which directly becomes a latent rebellion against logic for the gambler. Unconscious aggression (against the parents who represent law and reality) is followed by a need for self-punishment, implying the psychical necessity of loss in the gambler. The cynicism, the apparent coldness, the mastery flaunted by gamblers is, in Bergler’s opinion, merely the mask covering a feeling of infantile weakness. The cynicism is an attempt to justify, or to attribute to everyone else, feelings as hostile as those that unconsciously the gambler harbors towards the parental figures. Superstition and ”magic” rituals are the rule, despite the vehement protests of gamblers on this topic. Just like the systems or martingales that are supposed to lead to winnings, these artifices are merely the crude expression of the infantile megalomanic belief in the capacity to steer destiny.

In this way, Bergler draws up a list of criteria that make it possible to ”define” the pathological gambler, in contradistinction to the ”social” or recreational gambler: habitual risk-taking, gambling taking over one’s life, pathological optimism, the incapacity to stop gambling, the mounting stakes, the thrill of the gambling.

Fenichel (1945) describes gambling as a ”fight against destiny”, and pathological gambling as a loss of control: ”Under the pressure of internal pressures, the playful character may be shed; the Ego can no longer control what it has got underway and is overcome by a vicious circle of anxiety and the violent need for reassurance, anxiety-provoking in its intensity. The primitive pastime has now become a question of life and death.“ Fenichel distinguishes elsewhere between ”compulsive neuroses” in which the subject is obsessed by the idea, as if imposed from without, of committing an act, which he struggles against, and ”impulsive neuroses” in which the act is committed in a way that is ego-syntonic. The basis for the classification of the DSM’s ”impulse control disorders” finds its origin here, and Fenichel classes pyromania and impulsive fugue states within the impulsive neuroses, alongside gambling.

Jacques Lacan (1978), in his “Seminar on The Purloined Letter”, poses the gambler’s question in a more philosophical and pithy way: ”What are you, figure of the dice I roll in your chance encounter (tyche) with my fortune? Nothing, if not the presence of death that makes human life into a reprieve obtained from morning to morning…”. In this ”meaningful” approach, psychoanalysis meets up again with philosophical, even cosmological questions.

The imperative dimension of the passion takes precedence over the interrogative component of gambling: defying the ”mechanical laws” of chance and their calculations, the gambler summons the Other to show itself and signify to him his right to existence, thus unveiling the terms of a terrifying mathematics of the relation to the Other, under the yoke of the ”ordalic” procedure. The logic behind the gambler’s compulsive ordalic behavior leads Marc Valleur (1991) to modify the Freudian equation of the gambler’s compulsion to lose: ”if he admittedly does not play to win, he does not play to systematically lose either, but rather for those breathtaking moments at which everything – absolute gain, ultimate loss – becomes possible.”

Cognitive approaches

Several works have examined the “irrational” beliefs seen in gamblers. In particular these works highlight the illusion of control in gamblers, failure to recognize the “independence of throws”, superstitions and illusory correlations. The illusion of control is that the gamblers attribute the results of purely random sequences to their ability or knowledge. This illusion of control is increased by all of the “pseudo-active” aspects of gambling (slot machines with levers, lottery tickets to be completed by the people themselves, etc.). They give themselves the ability to predict results more or less “magically”, for example by making “martingales”.

Whatever the gambling, slot machines, roulette or others, some gamblers believe that the results of a gambling sequence will depend on the results of previous “throws” whereas the systems in question are designed for each turn to be independent of the others. The gambler’s mistake is in believing that a losing series must be followed by a winning series and the mistake with the “winning series” in believing conversely that the series will necessarily continue. These two mistakes are variants of non-recognition of the independence of throws. The “chase”, the attempt to repeat a winning throw, is often described as being specific to excessive gambling but sometimes as a variant of these mistakes.

Finally, superstitions and illusory correlations, which are extremely common and varied, are sometimes encouraged by gambling advertising or systems. “Near wins” are reinforcing factors for the gambling behavior.

It should be noted however that semi-ability gambling do exist, in which knowledge (for example, prognostics) or the gambler’s skill (for example poker) has some effect and which also leads to excessive gambling situations.

Cognitive errors are seen in all gamblers and are undoubtedly more common in excessive gamblers. This, however, does not establish a causal relationship. Greater knowledge of statistics, probabilities and the gambling systems only has very limited influence on gambling behavior itself.

Some authors describe a strategy of escape from reality or negative affect in problem gamblers and a search for distraction by involvement in a replacement activity. The gambling is also used to “fill a gap”, to take the place of a socialization and to avoid responsibilities. A vicious circle develops in the gamblers themselves, the illusion of control playing a (secondary) role in maintaining the process.

Many works that have studied gamblers’ excitement during gambling sequences in the “natural” situation show that excitement is greater with wins. The idea of tolerance vis-à-vis this excitement in regular gamblers has yet to be proven however.

The relationship between gambling, risk taking and sensation seeking is complex and requires the different types of gambling, the history of gambling behavior and the typology of gamblers to be taken into account. Sensation seeking can be seen as an indicator of a tendency towards gambling but does not distinguish between problem gamblers and other gamblers.

The risk-taking and sensation-seeking dimensions can also be placed in the person’s trajectory, the gambling behavior not having the same significance in the different phases of the trajectory. Initially “adventurous” behavior when the gambling is discovered and initiation occurs can, as the habit develops, become a refuge in a now predictable routine.

Impulsivity and self-regulation capacity

Impulsivity, which results from difficulty in self-regulation or self-control lies at the heart of the definition of pathological gambling. Many studies have examined the relationships between problem/pathological gambling and controlled versus more automatic (motivational) aspects of self-regulation.

The relationships between problem or pathological gambling and controlled aspects of self-regulation have been examined in two ways: from questionnaires that assess impulsivity (which is considered to result from weak self-regulating ability), and using cognitive tasks examining executive functions (such as inhibition, planning and flexibility capacities) and decision-making capacities.

Most of the studies using impulsivity questionnaires have shown higher levels of impulsivity in pathological gamblers than in control participants. These studies have identified positive links between high level impulsivity and the profile of high-risk gamblers in the general population or in populations of university students. The level of impulsivity is also a predictive factor for the severity of the symptoms of pathological gambling and is also associated with a greater likelihood of abandoning psychotherapeutic management and of psychotherapeutic management being less effective.

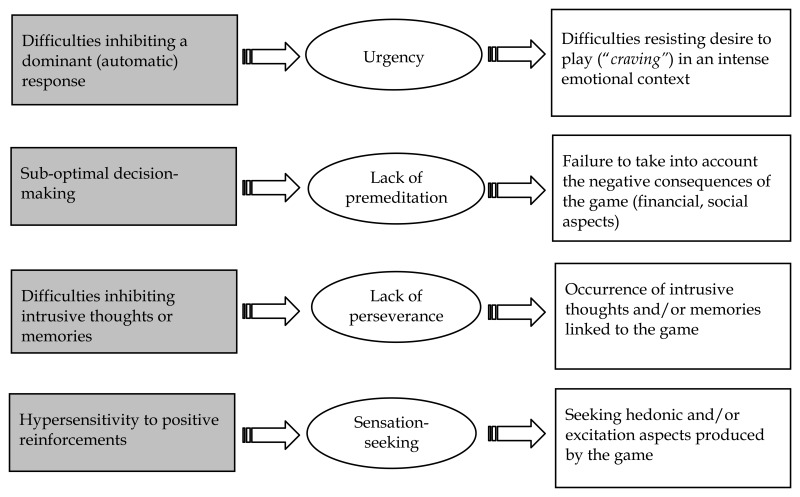

The studies that have examined controlled aspects of self-regulation using cognitive tasks have produced more inconsistent results than those based on questionnaires. However, difficulties, linked to pathological and/or problem gambling, have been found in the ability to inhibit a dominant (or automatic) response, in the ability to take into account the positive or negative consequences of a decision, in the ability to defer rewards, to see oneself in the future and to estimate time.

The relationships between problem/pathological gambling and the automatic aspects of self-regulation (mostly examined by questionnaires assessing sensation seeking or related concepts) are markedly less clear that the relationships between problem/pathological gambling and controlled (executive) aspects of self-regulation. This problem is likely to be due to the fact that the scales used to examine sensation seeking do not assess the specific activities through which a gambler seeks reward and/or stimulation. Nevertheless, studies that have examined sensation seeking in gamblers have provided some useful data suggesting future avenues for research. A positive relationship has been found between sensation seeking and the number of different gambling activities performed. Regular gamblers are also found to be different in terms of their level of sensation seeking depending on the gambling activities they perform. Gamblers who prefer casino gambling have greater sensation-seeking desires than those who bet on horse races and people who bet at racecourses have higher sensation-seeking desires than those who gamble in cafes.

It appears for the most part that self-regulation difficulties are associated with problem/pathological gambling. However, the contribution made by those studies which have examined this question is still relatively limited as the studies were performed without clear reference to a theoretical model specifying both the different facets of self-regulation or impulsivity (with the associated cognitive and motivational mechanisms) and the contribution of each of these facets to development, maintenance and/or relapse of pathological gambling. In particular, this involves taking account of the complex relationships between the automatic (motivational) and controlled (executive functions and decision-making) aspects of self-regulation at different times in the creation of gambling habits. The shift in status from a “social” gambler to a “problem” gambler may occur as a result of the interaction between hypersensitivity to positive reinforcements from the game (motivational aspects of impulsivity) and weak executive abilities (executive aspects of impulsivity).

Illustration of the hypothetical relationships between problem/pathological gambling and the different executive and motivational mechanisms underpinning the different facets of impulsivity distinguished by Whiteside and Lynam (2001)

Finally it must be noted that the characterization of the pathological gambler as essentially impulsive, irrational and dependent (a characterization determined largely by the social and cultural context in which the “pathological gambling” concept is born) has considerably limited the investigation of the many psychological (conscious and unconscious) factors that motivate the gambler. In addition, this belief has led to transversal and static investigations of people considered to belong to a distinct delineated category rather than considering problem gambling as a specific stage, which may affect a large number of people in their gambling trajectory.

Vulnerability and trajectory factors

Risk and vulnerability factors are firstly those factors relating to the object of addiction, or structural factors, secondly those relating to the environment and context, or situational factors, and finally factors related to the subject, or individual factors.

From the perspective of the structural factors, the different types of gambling have attracted increasing attention in the international scientific literature, with the idea that not all include the same risk of addiction. To this end, several authors believe that the shorter the time between bet and expected gains the greater is the possibility that the gambling will be repeated and the greater is the risk. This finding undoubtedly merits confirmation via correctly conducted studies.

The impact of a large initial gain is one of the classical factors for the development of excessive gambling. This factor is seen in studies on pathological gamblers encountered during consultation visits.

The development of Internet gambling, which has been very evident for a few years, requires consideration to be given to the place and specific impact of this medium. The occasional studies on this subject emphasize the concepts of anonymity, accessibility, disinhibition and comfort which are liable to predispose to abuse and addiction practices. The impact of the offer and availability of the gambling in terms of risk factors have been considered in the same way as for other addictions.

From the perspective of the situational factors, it is above all the socio-economic factors which need to be stressed, with the clearly established concept that reduced social support and low level of income-employment often correlate with the prevalence of pathological gambling and high risk gambling. Several studies have examined the position and contribution of parents in terms of risk factors or protection against excessive gambling in their children. These stress that the place and acceptance of the gambling by the parents have an impact on the frequency of gambling behavior and gambling-related problems in children, and also that supervisory authority is a more protective position than a more lax, or conversely authoritarian family situation.

From the perspective of individual factors, initiation into gambling occurs in most cases during the adolescent period. This has been shown by studies on pathological gamblers attending specialist care structures. Early contact with gambling appears to be a severity factor reflecting what is seen in psychoactive substance addictions. The elderly are a high-risk population for lotteries and slot machines.

A family history of pathological gambling (with the concept of family aggregation), addictive behavior, anti-social personality and, to a lesser extent, other mental disorders, appears to be more prevalent in pathological gamblers. A past history of abuse in childhood has been found to be associated with earlier and more severe pathological gambling behavior. Similarly, psychiatric co-morbidities are undisputable risk factors for beginning gambling behavior when they pre-exist and for worsening gambling behavior in all situations.

The risk and vulnerability factors appear to be similar to those found in all addictive behaviors, particularly addictions to psychoactive substances. The person who is most at risk of becoming involved in pathological gambling behavior would therefore appear to have the profile of a young unemployed male with low income, unmarried and poorly socially and culturally integrated.

Several studies have specifically examined the association between pathological gambling behavior and other addictive behaviors, notably alcohol and impulsive and delinquent behavior, particularly in young men. These reveal that early behavioral and attention disorders precede various addictive and behavioral disorders. As with most of the other addictive behaviors pathological gambling would appear to result from a combination of different risk and vulnerability factors (in variable proportions), a combination which characterizes the profile of each situation and trajectory on an individual case basis.

In terms of trajectories, there are few dedicated studies and most do not provide information about the exact chronology of the history of more or less well-controlled gambling practices.

A few correctly conducted studies over recent years have however made it possible to measure a lack of stability over time in the pathological gambler.

The fact that these gambling problems develop individually on a more transient and episodic basis, rather than continuous and chronic, is a strong argument for developing long-term general population cohort studies. These studies should better identify the complex reality of these pathways and the factors involved in periods of both remission and relapse in order to extract the maximum of information in terms of prevention and treatment indications.

Input from the neurosciences

Most of the data published in the neurosciences field concern addictions to psychoactive substances. However, as non-substance addictions have the same symptoms and even a withdrawal syndrome, these clinical features can be considered to reflect the same cerebral dysfunction and to originate from a common pathophysiology, namely Addiction6. It is generally accepted that the Addiction syndrome is the end of a process which forms a cycle (or spiral) as 80% of cases relapse after withdrawal.

The shift from occasional to chronic use and Addiction is clinically characterized by progressive loss of control of the consumption behavior and compulsive seeking (craving) and consumption of the object, despite the serious consequences which may occur for the individual person, his family and close friends, and despite the development of a negative affective state which precipitates relapse.

At an advanced stage of a consumption habit which becomes increasingly impulsive, the person enters an alienating spiral entirely centered on the object alone.

Once Addiction is established, i.e. a compulsive state, the person falls into another spiral.

At this end stage of the process, the person is extremely distressed and the cerebral changes are more difficult to reverse, leading to a chronic disease state of Addiction.

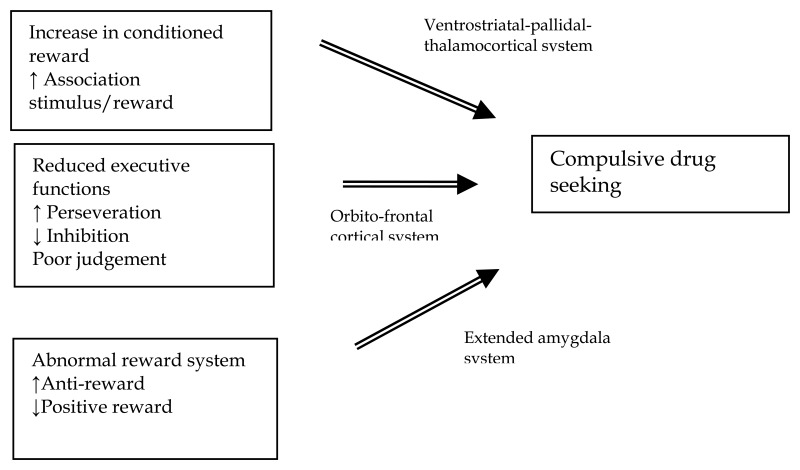

Neuropsychological representation of the common syndrome of Addiction: relationship between symptoms as described clinically and the corresponding regions and systems given the functions which they control (from Koob and Le Moal, 2001from Koob and Le Moal, 2006 and 2008)

The central stress and emotion systems (characterized by different neurotransmitters) contribute to a pathophysiological function which defines a powerful motivational state reflected by a shift from impulsive behavior to compulsive behavior.

It is important to stress that Addiction affects relatively few people compared to the number of occasional consumers of the object of addiction. Many authors consider that an object of addiction is only addictogenic when it is consumed by an already vulnerable person.

Understanding why some people succumb to addiction and others do not (up to the point of apparent resilience) is an essential question. It is accepted that a person will more easily develop a new addiction if he/she has previously succumbed to an object of addiction, although interchangeability of objects is classically seen. Vulnerable people are generally polyconsumers of addiction objects. In addition, this vulnerability may occur as a result of various psychopathological co-morbidities, poor conditions in terms of education and environment, personality disorders and stressful lifestyles. In order to understand the addiction process it must therefore be examined in a whole life context and, because of its early diathesis, be examined from a very young age onwards. Improved identification of vulnerability would help preventive intervention based on the solid concept of “why” inter-individual differences exist and “how” the addiction process is entered. Whilst vulnerability and co-morbidity have neurobiological translations, considerable progress is needed before obtaining scientific reference data. Although gambling addiction clearly has specific features it is accepted that the sources of vulnerability are the same as for other addictions.

Gaming addiction (particularly gambling and internet addictions) is a very interesting question for the neurosciences. The key factor in gamblers is the speed between perception and execution. Decision-making is based obviously on knowledge, skill and memories, the quality and relevance of which probably take account of the speed of decision and action. The involvement of pre-established mental sets also exists with drugs of abuse and are the cause of relapses; environment indices and mental representations almost immediately trigger imperious, impulsive, compulsive consumption and even a withdrawal syndrome in a person who has not consumed for several weeks. Neurobiological research is being directed towards identifying the substrates involved in the two situations which appear to be based on stimuli-response associations in memories, knowledge and cognitive systems.

Neuropsychological approaches

Considering excessive gambling to be a “non-drug addiction” raises the hypothesis that the risk of becoming dependent on the gambling and overindulging in it is related to a drug user’s risk of drug dependency. This appears to be a central question in thinking about excessive gambling: is the gambling a drug in the same way as psychostimulants, opiates, alcohol or tobacco? Does this type of addiction involve the same neurotransmitters?

In drug consumption mechanisms, the dopaminergic system is a determining factor as it modifies the functioning of a specific set of neurons, the “reward circuit”. This circuit relays all of the body’s external and internal information and enables the person to recognize the existence of potential satisfactions of all sorts through external perceptions: food, heat, sexual pleasure, etc. Dopaminergic neurons are not strictly speaking part of the reward circuit although their activation stimulates the circuit and provokes a sensation of satisfaction. Results of neurobiological research over recent years have convinced the main part of the scientific community that dopamine is fundamental to all pleasure-related events.

The stage which still has not been widely studied is the involvement of dopamine in drug dependency. It is in fact tempting to think that it is the pleasure produced by the drug that the consumer is no longer able to ignore. This would imply that the pleasure, and therefore dopamine, causes the drug addict to seek to consume his/her substance. It has long been noted by clinicians that drug addicts relatively quickly lose the pleasure from drug consumption in favor of seeking a state which more closely resembles a necessary or essential relief. Anglo-Saxon authors describe a shift from “liking” to “wanting”. We also know that a drug addict’s vulnerability to re-use a drug may last for several months or even years after he/she has given up the drug. Until now, all of the biochemical indices measured in animals following iterative administration of drugs have returned to normal after a few days or no more than one month after the last dose.

By studying modulators other than dopamine, i.e. noradrenalin and serotonin, these latter modulators have been shown to regulate each other (being coupled) in normal animals, i.e. in those which have never consumed drugs. This coupling reflects an interaction between noradrenalin and seritoninergic neurons with the result that both sets of neurons mutually activate or inhibit each other, depending on the external stimuli perceived by the animal or person. During repeated drug use this coupling disappears. The uncoupling and uncontrollable over-reactivity which it produces between the noradrenergic and serotoninergic systems may be responsible for the malaise experienced by drug addicts. Retaking the drug would then enable artificial recoupling of the neurons creating temporary relief which may explain the relapse. The drug in this case would be the most immediate way to respond to the malaise.

The question raised now is whether the uncoupling which is obtained with cocaine, morphine, amphetamine, alcohol or tobacco can be obtained by gambling. It has been clearly shown that the very great majority of excessive gamblers suffer from concomitant diseases. These diseases, particularly addiction to substances such as tobacco and alcohol which develop in parallel to the excessive gambling behavior, may account for the pathological form of the gambling.

However, psychiatrists point out that pathological gamblers exist who have no addiction or any other concomitant psychological disorders. It is not therefore possible to exclude the possibility that simply overindulging in gambling may, as for drug abuse, cause changes to the functioning of the central nervous system such as those described above. One of the hypotheses which could be put forward is that in some people, stress and distress which the gambling can cause chronically increase glucocorticoid secretion and, in the absence of the product, reproduce neuronal activations and analogous uncoupling to what is seen with addictive substances. Preclinical research should be conducted in order to study whether chronic stress situations or secretion of endogenous molecules such as glucocorticoids can alone reproduce the neurochemical effects produced by drug abuse.

Clinical approach

For the clinician, addiction can be defined as a condition through which behavior liable to give pleasure and relieve unpleasant feelings is adopted to an extent that it results in two key symptoms: repeated failure to control this behavior and continuation of the behavior despite its negative consequences.

There are some arguments to justify pathological gambling belonging to “impulse control disorders” according to the DSM-IV-TR by the inability to resist the impulse or the attempt to commit an act which is harmful to the person him/herself or to other people, particularly the high level of impulsivity in pathological gamblers confirmed in several studies. Impulsivity however appears to be only one of the features of pathological gambling. Several published works also highlight the heterogeneous nature of this category in the DSM and have put forward the hypothesis that impulse control disorders belong to the behavioral addictions category, which would therefore group together pathological gambling, kleptomania, pyromania, trichotillomania, intermittent explosive disorder and also compulsive buying, compulsive sexual behavior and compulsive Internet use.

The following ideas emerge from the large literature on the relationship between obsessive compulsive disorders (OCD) and pathological gambling: clinical arguments (intrusive, incoercible thoughts, loss of control of mental activities) highlight the compulsive dimension of gambling ideas and suggest that pathological gambling belongs to the “obsessive compulsive disorders spectrum”. There are many arguments however in the other direction: obsessive gambling ideas in the gambler are egosyntonic (driven by seeking well being) whereas the obsessive ideas in OCD are by definition intrusive and egodystonic (they cannot be ignored and are a source of distress). There are also no clear epidemiological arguments showing co-occurrence of OCD and pathological gambling. Neuropsychological findings are discordant, some works showing similar deficits in executive functions related to the frontal lobe in people with OCD and pathological gamblers, whereas these similarities have not been found in other studies.

Ultimately there are no formal arguments to enable pathological gambling to be seen as an OCD related disorder even though the compulsive dimension of the behavior is apparent.

In most of the recent publications, pathological gambling is considered to be a behavioral addiction. There are clinical arguments to support this position: the clinical phenotypes of the gambling and substance addiction (DSM-IV-TR) are very similar, including the presence of withdrawal symptoms and changes in tolerance (increased challenges over time) in the gamblers. Of the other clinical aspects common to gambling and addictions, a higher prevalence in young adults, the existence of early onset rapidly progressive forms, the existence of late onset rapidly progressive “telescoped forms” in women, and the impact of socio-cultural and ethnic factors. High rates of co-morbidities between pathological gambling and addictions and also between pathological gambling and numerous mental and personality disorders are reported in all of the studies.

Finally, some common aspects to treatment are seen: usefulness of motivational therapies to initiate a genuine request for withdrawal; use of group therapies (“Gamblers Anonymous” based on the model of “Alcoholics Anonymous”), usefulness of cognitive-behavioral therapies in pathological gambling as in most addictions.

There are therefore many clinical, epidemiological, biological and therapeutic arguments to consider pathological gambling as a non-drug addiction. Like all addictive diseases, the behavior requires impulsion and compulsion. Considering pathological gambling to be an addiction has the advantage of focusing interest on this frequently misunderstood disease, promoting its screening and management in addiction center treatment programs and finally considering a sub-syndrome category of “gambling abuse,” based on the model of substance abuse in the successive versions of DSM.

Screening and diagnostic tools

The questions of screening and diagnosis must be considered with reference to their objectives: is the purpose to consider primary prevention activities, with the ambition of making the largest number of people at risk from their behavior aware of the situation, or is the purpose to identify behavior which is already sufficiently problematic to have resulted in a certain amount of characteristic damage in order to justify a specific treatment approach? Several tools are used throughout the world for excessive/problem and pathological gambling.

The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) is a self-completed questionnaire designed from the DSM-III and containing twenty items. The SOGS is the reference tool used to identify pathological gambling which is by far the most widely used in the world. However, some limitations of this tool are regularly emphasized in terms of its psychometric properties. Several authors refer to a certain over-estimation of the prevalence of pathological gambling. As it is already an old tool some diagnostic changes have not been incorporated. Finally, the relevance of the tool in the youngest populations is debated despite the existence of a version adapted for adolescents (the SOGS-RA).

The pathological gambling section of the DSM-IV (DSM-IV-gambling) is a reference tool to diagnose pathological gambling. In this case, as is usual for the DMS, this involves diagnostic criteria which can be used by the clinician in his/her evaluation. In terms of its psychometric properties the reliability and validity of the DSM-IV-gambling have been demonstrated in many studies. The DSM-IV-gambling is recognized to be more discriminatory than the SOGS and the average prevalence of pathological gambling found with the SOGS is considered to be twice as high as with the DSM-IV-gambling.

Some adaptations of the DSM-IV-gambling need to be mentioned: the DSM-IV-J (juvenile) and DSM-IV-MR-J which are already adaptations of the DSM-IV-gambling for adolescents and the NODS7 which is a general population screening tool using a self-completed questionnaire.

The pathological gambling section of the International Classification of Diseases (CIM-10-gambling) is an equivalent of the DSM-IV-gambling created by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1993. The CIM-10 gambling is very widely used in clinical practice and very little used in research. There are few publications describing its psychometric properties.

The Gamblers Anonymous self-completed questionnaire (GA-20) is a twenty question self-evaluation tool very widely used in the United States and in many other countries, although there are practically no validation studies available for it. It is nevertheless considered to be very poorly discriminatory.

A number of other tools also need to be listed:

- the LIE/BET questionnaire is a pre-screening general population tool with 2 items equivalent to criterion 2 (need to play with increasing sums of money =BET) and criterion 7 (=LIE) of the DSM-III-R which seems to have useful psychometric properties;

- the Canadian problem gambling index (CPGI) is a nine item screening questionnaire adapted for Canada in two versions, English and French, which appears to offer good reliability and validity according to the literature. This tool has the merit of providing intermediary prevalence rates for pathological gambling between those seen with the DSM-IV-gambling and SOGS;

- the Structured Clinical Interview for Pathological Gambling (SCI-PG) is a clinical interview constructed from the DSM-IV and is therefore compatible with the SCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders) for gambling. It appears to offer good validity at different levels;

- the Gambling Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (GSEQ) and the Addiction Severity Index-Gambling (ASI-G) are two tools whose clinical interest remains to be demonstrated: the first is a self-completed evaluation questionnaire on the person’s perceived effective control of his/her gambling behavior and the second is an attempt to validate a five item score for gambling to include in the Addiction Severity Index, the most widely used multi-dimensional evaluation tool in the world for psychoactive substance addictions.

Screening and diagnostic tools for pathological gambling have therefore existed for around twenty years and are described in validation studies which guarantee good psychometric properties for several of these tools (this applies particularly to the SOGS, DSM-IV and CPGI). The SOGS and CPGI are screening tools whereas the DSM-IV-gambling is more clearly a diagnostic tool.

Nevertheless, important differences in terms of the prevalence of pathological gambling and high risk gambling are found in some studies using these different tools, which raises questions about thresholds and calls for further studies. Similarly, the relevance of these tools in younger and older populations is currently hotly debated.

Main screening and diagnostic tools for pathological gambling

| Tools | Estimate validity |

|---|---|

| South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) | Sensitivity from 0.91 to 0.94 |

| Lesieur and Blume, 1987; translated into French by Lejoyeux, 1999 | Specificity from 0.98 to 1 |

| Positive predictive value 0.96 | |

| Negative predictive value 0.97 | |

| Pathological gambling section of the DSM-IV | Sensitivity from 0.83 to 0.95 |

| APA, 1994 translated into French by Guelfi et al., 1996 | Specificity from 0.96 to 1 |

| Positive predictive value from 0.64 to 1 | |

| Negative predictive value from 0.62 to 0.91 | |

| Gamblers Anonymous self-completed questionnaire (GA-20) | No validation study |

| Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI) | Good reliability and validity |

| Structured Clinical Interview for Pathological gambling (SCI-PG) | No validation study |

| Gambling Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (GSEQ) | No validation study |

| Addiction Severity Index Gambling (ASI-G) (Mc Lellan et al., 1992) | No validation study |

In a general population: 1 to 2% problem and pathological gamblers

More than 200 prevalence surveys were found in the international literature, conducted mostly in North America, Australia and New Zealand. The great majority of these were specific surveys centered on the question of gambling. The problem was examined in some instances as part of a broader investigation on a health or mental health subject. This approach offers additional value as it allows an in-depth analysis of the relationships between determinants and individual health characteristics and problem gambling behavior.

Most of the studies produce estimates of “life long prevalence” and/or “year prevalence”, i.e. they define the proportion of the population surveyed which met the number of criteria set by the tools to identify problem or pathological gambling during their lives or during the previous year. A very clear change has been seen over time, with a progressive loss of interest in the concept of “life long prevalence”, “year prevalence” being preferred. This is due both to the difficulty of correctly measuring the former, which is more sensitive to memory problems and also to the fact that the conceptual basis on which it was constructed is fragile. Interest for this concept has waned since the chronic nature of pathological gambling has been put in question.

There is a very wide range of identification tests used in the prevalence surveys, meeting a similar wide range of concepts. Nevertheless, three main identification tools predominate in the application to epidemiology: the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) (by far the most widely used), the adapted DSM-IV test and the Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI). Similarly, two concepts emerged:

- “pathological gambler” describing people whose state or behavior satisfies certain criteria of clinical diagnosis or a test questionnaire;

- “problem gambler” describing people who are not classified as pathological but who meet some of the criteria indicating difficulties with their gambling behavior. A fully extensive definition of problem gambling also includes pathological gambling.

The vast majority of the prevalence surveys on problem gambling involve adults. Most of the international literature examines the question of gambling. Studies on Internet addiction or video games (playing) are more recent, fewer in number and still centered on conceptual and methodological problems.

The prevalence level is highly dependent on the tool used, SOGS producing higher prevalence values than the DSM-IV and the CPGI producing intermediary prevalence values. This point was identified by some authors of meta-analyses and surveys which have simultaneously used several identification tools. However, it remains very controversial in the literature.

This situation does not facilitate prevalence comparisons in problem gambling in the different countries which have conducted national surveys on the subject. Nevertheless, two countries emerge with relatively high general population prevalence (problem gambling plus pathological gambling around 5%): United States and Australia. The prevalence found in the few European countries which have conducted these studies, mostly in Northern Europe, are far lower, between 1 and 2%, similar to the findings in Canada and New Zealand. Differences in prevalence between countries are still widely debated. The most common hypothesis put forward is differences in accessibility to gambling.

Average prevalence values for adults (2.5% for problem gambling, 1.5% for pathological gambling) and adolescents (15% for problem gambling, 5% for pathological gambling) have been established (using a complex weighting) from 160 prevalence studies in North America. These estimates should be seen as orders of magnitude. There is considerable dispersion of results around these mean values, particularly for adolescents.