Know Your Chances: Understanding Health Statistics is hereby licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license, which permits copying, distribution, and transmission of the work, provided the original work is properly cited, not used for commercial purposes, nor is altered or transformed.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Welch HG. Know Your Chances: Understanding Health Statistics. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 2008.

Imagine that you could take a pill that completely protected you against catching a cold. If the pill had no downsides—it was free and convenient and had no symptom or life-threatening side effects—it might sound attractive. But what if the pill caused half the people who took it to have heart attacks? Not so attractive. The point is that focusing solely on a benefit without considering the downsides can be deceptive, even dangerous. The next time you see an ad for a seemingly great new medication or hear a news report touting some medical breakthrough, remember that benefit is only half the story. To judge the value of an intervention, you have to consider potential benefits and downsides together. In the next few pages, we’ll look at some examples and do just that. And, as we did before, we won’t consider cost or convenience (that’s your job) but will instead focus on side effects.

Let’s start with Lunesta, the sleeping pill. Earlier we looked at its side effects. The following table, which summarizes findings from the largest and longest-running scientific study of Lunesta, lists the drug’s benefits as well as its side effects so that you can get the whole story.1 It begins by describing some key facts about the study itself: who was studied, how many were studied, and for how long.

788 healthy adults who suffered from insomnia—sleeping less than 6.5 hours per night and/or taking more than 30 minutes to fall asleep—for at least a month were given Lunesta or a placebo nightly for 6 months. Here’s what happened.

| What Difference Did Lunesta Make? | Starting Risk (Placebo group) | Modified Risk (Lunesta group, 3 mg/night) |

|---|---|---|

| Did Lunesta help? | ||

| Lunesta users fell asleep faster (15 minutes faster due to drug) | 45 minutes to fall asleep | 30 minutes to fall asleep |

| Lunesta users slept longer (37 minutes longer due to drug) | 5 hours, 45 minutes of sleep | 6 hours, 22 minutes of sleep |

| Did Lunesta have side effects? | ||

| Life-threatening side effects | 0% in both groups | |

| No difference between Lunesta and placebo | (none observed in this study) | |

| Symptom side effects | ||

| Unpleasant taste in the mouth (additional 20% due to drug) | 6% 6 in 100 | 26% 26 in 100 |

| Infections (mostly colds) (additional 9% due to drug) | 7% 7 in 100 | 16% 16 in 100 |

| Dizziness (additional 7% due to drug) | 3% 3 in 100 | 10% 10 in 100 |

| Next-day drowsiness (additional 6% due to drug) | 3% 3 in 100 | 9% 9 in 100 |

| Dry mouth (additional 5% due to drug) | 2% 2 in 100 | 7% 7 in 100 |

| Nausea (additional 5% due to drug) | 6% 6 in 100 | 11% 11 in 100 |

The table should look familiar—it’s just a modification of the tables we constructed in earlier chapters. It shows what people experienced without Lunesta (the starting risk numbers) and with Lunesta (the modified risk numbers). The table is divided into two parts: the top lists the benefits (did Lunesta help?) and the bottom lists the downsides (did Lunesta have side effects?). Providing these two types of information together—and in the same format—makes it possible for you to focus on the real issue at hand: do you believe that the potential benefits are worth the potential side effects?

As you make this judgment, remember to ask one of the key questions we discussed in chapter 4: “Does this risk reduction information reasonably apply to me?” If you are like the people who participated in the study, the table should be a good guide for what to expect if you take the medicine. In this case, being “like the people in the study” means that you’re between the ages of 21 and 69 and that you suffer from insomnia (as the study defined it). In addition, you don’t have a history of substance abuse, don’t use medications or supplements known to affect sleep, and haven’t been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

The less you are like the people in the study, the less you can count on the table to predict your experience. For example, no one knows how the drug works in the elderly or in children—much less whether it is safe. (The FDA has approved it only for adults.) And if you’re taking medications that affect sleep, it’s hard to know how interactions with those drugs will alter Lunesta’s benefits or side effects—other medications taken in conjunction with Lunesta may make Lunesta more or less effective, and they might alter the frequency or intensity of side effects.

Here’s how we weighed the benefits against the side effects. To us, the benefits of the drug—falling asleep 15 minutes faster and sleeping 37 minutes longer—seem quite small. In fact, on average, the people in the study who took Lunesta still met the definition of insomnia used in the study even after they took the medication (that is, they still slept less than 6.5 hours and took 30 minutes or more to fall asleep). And we were also struck by the frequency of the bothersome side effects. Overall, we thought that the drug didn’t seem to help much and that you would stand a good chance of experiencing some bothersome side effects. We were not impressed.

Remember, however, that what matters is your response. How do you weigh the benefits and the side effects? How important are the outcomes to you? You might feel that it’s well worth giving the drug a try. You might quickly learn whether it helps or whether it bothers you.

Now let’s take another look at Nolvadex (introduced in the previous chapter), the drug used to reduce the chance of developing a first occurrence of breast cancer. The following table provides the information that a woman would need in order to decide whether to take Nolvadex to reduce her breast cancer risk.2 Looking at benefits and side effects together can help a woman make an informed decision about whether the drug is “worth it” to her.

13,000 women age 35 and older who had never had breast cancer but were considered to be at high risk of getting it were given either Nolvadex or a placebo each day for 5 years. Women were considered to be at high risk if their chance of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years was estimated at 1.7% or higher (an estimate arrived at by using a risk calculator available at www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool). Here’s what happened.

| What Difference Did Nolvadex Make? | Starting Risk (Placebo group) | Modified Risk (Nolvadex group, 20 mg/day) |

|---|---|---|

| Did Nolvadex help? | ||

| Fewer Nolvadex users got invasive breast cancer | 3.3% 33 in 1,000 | 1.7% 17 in 1,000 |

| No difference in death from breast cancer | About 0.09% in both groups 0.9 in 1,000 | |

| Did Nolvadex have side effects? | ||

| Life-threatening side effects | ||

| Blood clots (in legs or lungs) (additional 0.5% due to drug) | 0.5% 5 in 1,000 | 1.0% 10 in 1,000 |

| Invasive uterine cancer (additional 0.6% due to drug) | 0.5% 5 in 1,000 | 1.1% 11 in 1,000 |

| Symptom side effects | ||

| Hot flashes (additional 12% due to drug) | 69% 690 in 1,000 | 81% 810 in 1,000 |

| Vaginal discharge (additional 20% due to drug) | 35% 350 in 1,000 | 55% >550 in 1,000 |

| Cataracts that needed surgery (additional 0.8% due to drug) | 1.5% 15 in 1,000 | 2.3% 23 in 1,000 |

| Death from all causes combined | About 1.2% in both groups | |

| No difference between Nolvadex and placebo | 12 in 1,000 | |

Either answer can be correct. There is no single “right” answer for every individual. We can’t tell you the “right” answer, nor can any other physician.

But you can’t even begin to make this choice without the numbers. That’s the point of this book. With the numbers, you can see that this decision is a close call. But it is much more difficult than the decision whether to take Lunesta. With Lunesta, you can simply try the drug and see whether you experience the benefits or side effects. In the case of Nolvadex, however, the benefits and life-threatening side effects take time to appear (the breast cancers, blood clots, and uterine cancer occurred over 5 years in the study), and they happen to relatively few people. So, even if you don’t get breast cancer, you can’t really know whether it’s because of the drug or just because you had good luck and weren’t going to get breast cancer anyway.

For a woman at high risk of breast cancer, deciding whether to take Nolvadex involves a delicate balance between her feelings about the benefit of the drug (lowering the chance of breast cancer) and the side effects, some of which are bothersome and some of which are life-threatening (though rare). The reason we consider this a close call is that it’s a situation in which women facing the same risk of breast cancer could reasonably make different choices. On the one hand, you might be a woman who is very worried about developing breast cancer and less worried about the side effects. You might reasonably decide to take the drug. On the other hand, you might be a woman who wonders about the wisdom of starting a medication to address problems that might happen in the future (as opposed to taking a medication for a problem you have now). You might be more worried about the problems that the medication can cause and might reasonably decide not to take the drug.

Alternatively, you might choose a middle ground. You might say to yourself, “I’d like to get the benefit of a reduction in breast cancer risk, and I can accept the small increase in the risk of blood clots and uterine cancer. But if the medicine starts making me feel poorly every day, it’s not worth it.” In this case, you might choose to try the medicine but stop it if you notice any of the common symptom side effects.

Before we leave Nolvadex, let’s take another look at the benefit section of the table. The first row indicates that Nolvadex reduced the chance of developing breast cancer. But the second entry states that Nolvadex did not reduce the chance of dying from breast cancer. How can we explain these two findings? It may be that the drug does in fact decrease the chance of breast cancer death, but the decrease was too small to be picked up in this particular study. (Fortunately, breast cancer deaths were rare among the 13,000 women who participated in the study: a total of 9 died from breast cancer over the 5 years, 6 in the placebo group and 3 in the Nolvadex group—a difference so small that it could have been due to chance, or a fluke.) If this is the case, perhaps a larger, 10-year study might show the small decrease. Another explanation is that the drug may prevent only cancers that are easy to treat and may not prevent the more aggressive forms, so that it really may not reduce the death rate.

No one knows (yet) why Nolvadex did not reduce the chance of breast cancer death. But this does not mean that Nolvadex is useless: avoiding a breast cancer diagnosis and the associated anxiety, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and so on is far from trivial. But our point is to emphasize that reducing the risk of getting a disease does not necessarily translate into reducing the risk of dying from the disease. This highlights the importance of knowing where you are on the pyramid of benefit discussed in chapter 5.

An Important Bottom Line: Death from All Causes Combined

There is one other entry in the Nolvadex table that deserves notice: the bottom row, which indicates that the risk of death from all causes combined was the same in the placebo group and the Nolvadex group. The reason you want to know about this statistic has to do with the potential life-threatening side effects of Nolvadex, such as blood clots or uterine cancer. Since these conditions can kill you, it’s important to look for any evidence that the drug increases the chance of death from all causes combined. If the drug did increase this chance of death, you’d certainly want to avoid taking it. If it decreased this chance, you’d probably want to take it—if the side effects were not extremely bothersome. In this case, because the drug did not change the chance of death from all causes, you have to make the decision based on the issues we discussed earlier.

The category “death from all causes combined” is a valuable statistic for another reason: there’s no ambiguity about it. To understand what we mean, consider the process of counting deaths from specific causes. Sometimes it’s hard to know what a person died from. For example, if someone developed severe pneumonia, which triggered a fatal heart attack, did that person die from pneumonia or heart disease? What if a drug caused fewer pneumonia deaths but more heart attack deaths in patients with pneumonia? It is extremely difficult to sort out these ambiguities. That’s why death from all causes combined is such a useful measure. There’s no way to make a mistake about it: the person is either dead or alive.

Unfortunately, very few medical interventions reduce the chance of dying from all causes combined. The exceptions tend to be drugs like Zocor (discussed in part two), which reduced deaths from all causes combined in a very-high-risk population, people who had already had a heart attack. This is because it reduced the most common cause of death—heart disease—in these patients. Breast cancer does not account for a big proportion of deaths in any age group (see the risk charts in the Extra Help section, pages 128–129); consequently, even eliminating breast cancer completely would make only a small difference in the risk of death from all causes combined. So it wouldn’t be “fair” to criticize Nolvadex for not decreasing a woman’s overall chance of death. But it’s always worth asking how an intervention affects the chance of dying from all causes combined—either as reassurance that life-threatening side effects do not outweigh other benefits or as additional confirmation of the benefit.

Making Decisions

Tables like the ones we’ve just examined summarize information about medical interventions in a way that clearly conveys the major benefits and side effects and how often they occur. They are helpful not only for consumers who want to make informed decisions about taking medications but also for people facing many other kinds of medical decisions: whether to have an operation, for example, or whether to undergo a screening test such as a PSA test for prostate cancer or a mammogram for breast cancer.

In fact, whenever you face an important medical decision (or other intervention, for that matter), we encourage you to look at such a table. Ask your doctor—or whoever is suggesting the intervention—for one. Or you can construct one yourself. That is, however, easier said than done. Tables like these, and even the data to use in them, are not readily available. But many people are working hard to improve the situation. We are currently collaborating with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to create such tables for prescription drugs. We call them “prescription drug facts boxes,” and we hope that they will be available soon.

Meanwhile, to help you find the numbers you need to construct tables, we’ve listed credible sources of health statistics in the Extra Help section (pages 130—132). All the sources in this list are independent groups that seek to present or summarize the benefits and side effects of medical interventions. It is not intended to be a comprehensive list, but it does include the resources we often use when we are looking for information.

While we are impressed by the quality of information these sources offer, the presentations can vary in how detailed they are and how easy they are to use. The first part of the list consists of sources created primarily for consumers. Unfortunately, these “patient” materials sometimes sacrifice the details you need (that is, the actual numbers) in the name of accessibility. So we encourage you to also explore the second part of the list, which includes sources designed for a physician audience. In these materials, you may find lots of technical terms and acronyms, and you certainly won’t find much poetry. But don’t be put off; these are great information sources and may be the best places to start looking for good data.

To the extent that you can complete the table with reliable information, you can be confident that you’re equipped to make an informed decision. But if you can’t fill in large parts of the table—for example, the scientific evidence is not yet available, or there is conflicting evidence—you need to proceed cautiously: you can only guess whether the drug, test, or treatment does more good than harm.

You should recognize, of course, that it makes sense to complete a table like this only when you’re facing important decisions with real alternatives. By real alternatives, we mean situations in which you can reasonably choose among different options. Sometimes it’s like deciding to put on a life jacket when your ship is sinking: there are no real options, and you just have to act. In the same way, no one would demand to see the scientific evidence that efforts to stop major bleeding after an accident are a good idea. There may also be times when you are facing important choices but are too sick or emotionally overwhelmed to participate in decisions. In this case, friends or family members (who are often looking for ways to be helpful) might be able to seek out information and evaluate the benefits and side effects of various options.

Most of medicine, however, is not about emergencies or situations that don’t include real choices. Fortunately, you usually have time to learn about and weigh various options.

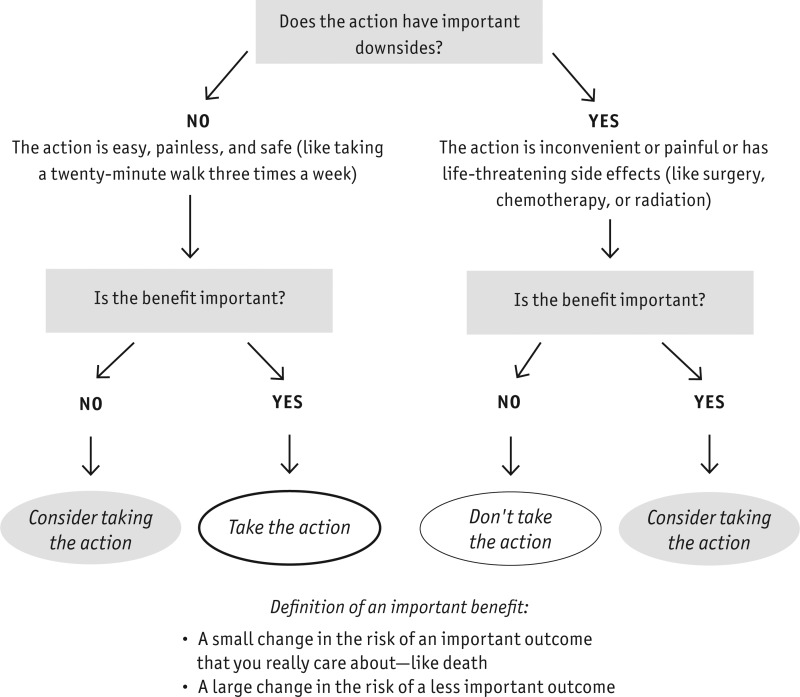

The diagram on page 84 summarizes our approach to deciding whether the benefits of a medical intervention outweigh its downsides. Whenever you hear about the benefit of a health intervention, you should ask yourself, “What are the downsides? Is it worth it?”

To answer that question, you must consider whether the action has important side effects, as we’ve been emphasizing in this chapter, and also assess the cost and inconvenience. If the action is a big deal or has important downsides—that is, it involves a lot of time, pain, or life-threatening side effects—you should insist on an important benefit, one that affects an outcome you really care about. The size of the effect matters, but even small changes in an outcome you care about a lot (like your chance of dying) can be an important benefit. On the other hand, if an intervention changes only a surrogate outcome or an outcome you don’t care about so much, the benefit would generally have to be pretty substantial before you would consider the intervention.

If the intervention does not have important downsides—it is as easy, painless, and safe as taking a twenty-minute walk three times a week, for example—you may want to do it even if the likely benefit is small (including surrogate outcomes).

For some medical decisions, figuring out whether the benefits outweigh the downsides is easy. But in many cases, it is a balancing act that requires you to carefully judge the importance of the benefits against the downsides.

- Do the Benefits Outweigh the Downsides? - Know Your ChancesDo the Benefits Outweigh the Downsides? - Know Your Chances

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...