Attribution Statement: LactMed is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-.

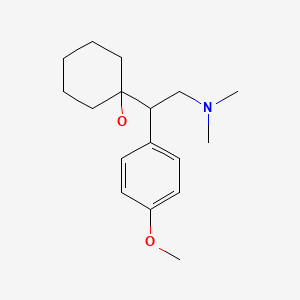

CASRN: 93413-69-5

Drug Levels and Effects

Summary of Use during Lactation

Infants receive venlafaxine and its active metabolite in breastmilk, and the metabolite of the drug can be found in the plasma of most breastfed infants; however, concurrent side effects have rarely been reported. Some experts feel that venlafaxine is not recommended during nursing,[1] but a safety scoring system finds venlafaxine use to be possible during breastfeeding.[2] Breastfed infants, especially newborn or preterm infants, should be monitored for excessive sedation and adequate weight gain if this drug is used during lactation, possibly including measurement of serum levels of desvenlafaxine (O-desmethylvenlafaxine), to rule out toxicity if there is a concern. Maternal poor metabolism by metabolic enzymes does not appear to result in excessive infant serum concentrations. Bruxism has also been reported in one infant. However, newborn infants of mothers who took the drug during pregnancy may experience poor neonatal adaptation syndrome as seen with other antidepressants such as SSRIs or SNRIs. Use of venlafaxine during breastfeeding has been proposed as a method of mitigating infant venlafaxine withdrawal symptoms,[3,4] but this has not been rigorously demonstrated.

Drug Levels

Venlafaxine is metabolized to a metabolite, desvenlafaxine, that has antidepressant activity similar to that of venlafaxine.[5]

Maternal Levels. Three mothers with infants aged 0.37, 1.3 and 6 months were taking venlafaxine in doses of 3.04 to 8.18 mg/kg daily for at least a week. Peak breastmilk levels of venlafaxine and its active metabolite, desvenlafaxine, occurred 1 to 3 hours after the dose in 2 of the mothers. Infants received an average of 7.6% (range 4.7 to 9.2%) of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage of venlafaxine plus desvenlafaxine.[6]

Six women averaging 7 months postpartum were receiving venlafaxine 225 to 300 mg daily for at least 18 days; 1 was taking the sustained-release (SR) formulation once daily and the others took 2 divided doses daily. In the women taking immediate-release product, the time of the peak milk levels averaged 2 hours (range 1.7 to 2.8 hours) for venlafaxine and 2.8 hours (range 1.8 to 4.2 hours) for desvenlafaxine. For the SR formulation, peak venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine levels occurred at 5.7 and 7.7 hours, respectively. The authors estimated that an exclusively breastfed infant would receive an average of 6.4% (range 5.2 to 7.4%) of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage of venlafaxine as the drug plus metabolite.[7]

Three women were taking venlafaxine during breastfeeding in doses of 37.5, 75 and 225 mg daily. Milk samples were taken 8 hours after a dose and measured for venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine. The infants were estimated to have received 11.8%, 3% and 6.3% of the weight-adjusted maternal dosage.[8]

In 3 women 8 to 30 weeks postpartum who were taking venlafaxine 75 to 225 mg daily, the authors calculated that their fully breastfed infants would receive an average of 5.2% of the maternal dosage, primarily as desvenlafaxine.[9]

A woman who was taking venlafaxine 375 mg daily during pregnancy and postpartum had a combined breastmilk level of 690 mcg/L of venlafaxine and 2 metabolites. The authors estimated that the breastfed infant was receiving at least 3.5% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.[3]

Two women who were 6.5 and 9.5 weeks postpartum and taking venlafaxine 75 mg and 225 mg daily had their milk measured at unreported times after their doses. The venlafaxine concentrations in their milk were 103 and 327 mcg/L, respectively.[10]

Eleven women taking an average of 194 mg of venlafaxine daily (1 as immediate-release and 10 as sustained-release) had their breastmilk venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine concentrations measured. The estimated excretion of the drug and metabolite into breastmilk was 8.1% (range 3.2 to 13.3%) of the weight-adjusted maternal dosage. The peak drug concentration in breastmilk occurred at about 8 hours after the dose; desvenlafaxine was the primary contributor to total milk concentration. The estimated infant dosage was 0.208 mg/kg daily (range 0.07 to 0.38 mg/kg daily),[11] which translates to 6.4% of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage.

A woman treated with venlafaxine 75 mg daily during the third trimester of pregnancy and during breastfeeding provided a trough milk samples during the first week postpartum. The milk level was 461 mg/L, with a calculated weight-adjusted percentage of maternal dosage of 8.8%. This value might be inaccurate because of the timing of sample collection.[12]

Random milk samples were obtained from 5 women taking a median dosage of 75 mg (range 37.5 to 150 mg) of venlafaxine daily had a median venlafaxine milk concentration of 102 mcg/L (range 7.5 to 568 mcg/L) and a median desvenlafaxine milk concentration of 371 (range 72 to 1031 mcg/L). The authors calculated that this represents a combined median infant dosage of 77 (range 12 to 163) mcg/kg daily of the two drugs.[13]

A woman was taking venlafaxine 75 mg daily during pregnancy and postpartum. Trough milk samples were taken before her dose on several occasions over a 1-year period. At delivery, her colostrum venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine concentrations were 34 and 428 mcg/L, respectively. At 10 days postpartum, milk concentrations were 168 and 13 mcg/L, respectively. At 2 months postpartum, milk concentrations were 144 and 442 mcg/L, respectively. At 6 months postpartum, milk concentrations were 171 and 606 mcg/L, respectively. At 12 months postpartum, milk concentrations were 96 and 319 mcg/L, respectively.[14]

A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model was used to predict nursing infant exposure to venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine under several maternal genetic conditions. Using peak milk levels (i.e., worst-case scenario) the estimated RIDs were1.7% for CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers, 6.6% for poor metabolizers (PMs), and 10.3% for PMs of all of the phenotypes CYP2D6, 2C9 and 2C19. Nevertheless, the estimated infant daily dose remained substantially below the toxic threshold level of 10 mg/kg identified in a previous study.[15]

Infant Levels. Three breastfed (extent not stated) infants aged 0.37, 1.3 and 6 months whose mothers were taking venlafaxine 3.04 to 8.18 mg/kg daily had undetectable (<10 mcg/L) venlafaxine and an average of 100 mcg/L (range 23 to 225 mcg/L) of desvenlafaxine in their plasma.[6]

Two mothers on stable doses of venlafaxine 75 and 150 mg daily exclusively breastfed their infants for 6 months. At ages 3 and 4 weeks, respectively, venlafaxine was undetectable (<10 mcg/L) in the serum of both infants. Desvenlafaxine was detectable in their serum at 16 and 21 mcg/L, respectively.[16]

Three breastfed (extent not stated) infants whose mothers were taking venlafaxine 37.5, 75 and 225 mg daily had blood samples taken 8 hours after the previous maternal dose. The infants, whose ages were 3, 10.4 and 14.6 weeks, had venlafaxine serum levels of 9 mcg/L, <3 mcg/L and undetectable; desvenlafaxine serum levels were <8, 7.5 and 12.5 mcg/L, respectively.[8]

Of 7 breastfed (extent not stated) infants with an average age of 7 months, including 1 set of twins, whose mothers were taking 225 to 300 mg of venlafaxine daily, only 1 (maternal dose 225 mg daily) had a measurable serum level of venlafaxine of 5 mcg/L (detection limit 1 mcg/L). Measurable desvenlafaxine serum levels were 3, 6, 20 and 38 mcg/L in 4 of the 7 infants.[7]

In 3 breastfed (extent not stated) infants aged 8 to 30 weeks whose mothers were taking venlafaxine 75 to 225 mg daily, their serum drug levels were 10.2% of those of their mothers, mostly as desvenlafaxine.[9]

Six nursing infants (average 20 weeks; range 7.3 to 60 weeks of age) whose mothers were taking an average of 206 mg daily of venlafaxine had their serum analyzed for venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine. Five were exclusively breastfed and 1 was about 50% breastfed. Five of the 6 had no detectable (<2 mcg/L) venlafaxine in their serum, and 1 had a concentration of 5 mcg/L. Two infants, including the one who was partially breastfed had no detectable desvenlafaxine in their serum; the other 4 had desvenlafaxine concentrations ranging from 4 to 243 mcg/L. This group of 4 infants had an average serum concentrations of the drug and metabolite of 37% that of their mothers' serum.[11]

A 7-day-old infant with apparent toxicity from breastmilk ingestion had blood venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine concentrations were 1.5 mcg/L and 9.2 mcg/L, respectively. Her mother was taking a daily dose of 150 mg of venlafaxine.[17]

A woman was taking venlafaxine 75 mg daily during pregnancy and postpartum. She breastfed her infant (extent not stated) for at least 12 months. Infant serum samples were taken on several occasions over a 1-year period. At delivery, the infant had serum venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine concentrations of 13 and 172 mcg/L, respectively. Serum concentrations decreased progressively to <5 and 16 mcg/L at 2 months of age and <5 + 6 mcg/L at 12 months of age.[14]

Effects in Breastfed Infants

No acute adverse effects or abnormal weight gain were seen in 3 breastfed infants who had detectable serum levels of desvenlafaxine.[6]

No adverse effects on growth or in sleep, feeding or behavioral patterns were noticed clinically in 2 infants who were exclusively breastfed for 6 months during maternal therapy with venlafaxine 75 and 150 mg daily.[16]

Three mothers took an average venlafaxine dose of 162.5 mg once daily. They breastfed their infants exclusively for 4 months and at least 50% during months 5 and 6. Their infants had 6-month weight gains that were normal according to national growth standards.[18]

Seven infants (including 1 set of twins) breastfed for 2.7 to 10.3 months during maternal venlafaxine therapy. Three mothers were taking venlafaxine since birth and 3 were started later. Denver Developmental Screening Tests in all infants were normal. All but 2 had normal growth; these 2 had decreased weight gain.[7]

In 3 infants aged 8 to 30 weeks whose mothers were taking venlafaxine 75 to 225 mg daily, no adverse reactions were noted clinically at the time of the study.[9]

A newborn infant whose mother had been taking venlafaxine 375 mg daily during pregnancy had symptoms of lethargy, poor sucking ability, and dehydration at 2 days of age. The infant was allowed to breastfeed and the symptoms subsided over 1 week. The authors concluded that the symptoms were likely withdrawal symptoms that were mitigated by the venlafaxine in breastmilk.[1] Another infant whose mother was taking venlafaxine 300 mg daily was reported by the same center. In this case, the infant's symptoms of withdrawal improved markedly on day 7 when breastfeeding was initiated, but no drugs levels were measured in milk or in the infant.[4]

Two nursing mothers were taking venlafaxine and quetiapine for postpartum depression; one was also taking trazodone. Their breastfed infants' development was tested at 12 to13 months of age with the Bayley Scales. Scores were within normal limits on the mental, psychomotor and behavior scales.[19]

Thirteen infants whose mothers were taking venlafaxine in doses ranging from 37.5 to 300 mg daily were breastfed (11 exclusively and 2 about 50%). Three of the infants were also exposed to a second psychotropic drug in breastmilk: 1 each of buspirone, trazodone, quetiapine. None of the infants had any adverse reactions reported by their mothers or in their medical records.[11]

Two nursing mothers who were 6.5 and 9.5 weeks postpartum were taking venlafaxine in doses of 75 and 225 mg daily, respectively, in addition to quetiapine for major depression postpartum; one mother was also taking trazodone. Their breastfed infants' development were tested at 9 to 18 months of age with the Bayley Scales. Both infants had scores that were within normal limits.[10]

A mother was taking venlafaxine 75 mg daily for depression and anxiety, although when the drug was started is not clear from the report. Her 1-month-old infant was seen in a pediatric clinic and was demonstrating agitation, infantile colic, drowsiness, increased startle response, jitteriness and sleeplessness. The symptoms began at 1 week of age and became progressively worse over time and with breastfeeding. The symptoms were possibly caused by venlafaxine, although whether they represent a withdrawal reaction of direct drug effects cannot be determined.[20]

A woman with depression and anxiety was treated with venlafaxine 300 mg daily monotherapy beginning at 20 weeks of pregnancy. On day three of life, the infant had extensor posturing and cycling of the limbs which was thought to be seizure related. Clinical examination was normal. Her suck was noted to be strong but uncoordinated and the infant fatigued rapidly. The infant was partially breastfed initially, but when breastmilk feeding was discontinued, the infant's alertness improved and she gained 314 grams over 7 days. The authors felt that venlafaxine in breastmilk might have contributed to the infant's lethargy, especially given the high maternal dosage. The symptoms were possibly caused by venlafaxine in breastmilk.[21]

A woman was treated with venlafaxine 75 mg daily during the third trimester of pregnancy and during breastfeeding. Pediatric evaluation including neurologic assessment and brain ultrasound were conducted during the first 24 hours postpartum. Further follow-up was conducted at 6 or more months of age. The infant's clinical status was comparable to unexposed infants from the same pediatric department.[12]

A woman taking venlafaxine 150 mg daily noticed that her infant was difficult to rouse and breastfed poorly. She stated that breastfeeding was frequently interrupted by apparent infant distress and easy fatigability. At 7 days of age, the mother sought medical attention. On admission to the ICU, the infant was somnolent, difficult to rouse and hypotonic. The infant’s weight was 3080 grams, with an average weight gain of 12 grams daily. On day 8, formula was substituted for breastfeeding with an improvement in alertness and weight gain. Although the infant’s serum venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine were relatively low, the infant’s symptoms were probably related to the drugs in milk.[17]

A woman was taking venlafaxine 75 mg daily during pregnancy and postpartum. She breastfed her infant (extent not stated) for at least 12 months. During the 1-year follow-up, no symptoms related to venlafaxine toxicity were observed in the infant and neurological development and weight and height were age-appropriate.[14]

Effects on Lactation and Breastmilk

Cases of galactorrhea and elevated serum prolactin have been reported in which venlafaxine played a primary or secondary role in the etiology.[19,22-29] Galactorrhea with normal prolactin levels has also been reported.[30] The prolactin level in a mother with established lactation may not affect her ability to breastfeed.

One mother who was nursing a 10.3-month-old infant reported that her milk letdown took longer after starting venlafaxine 1 month earlier.[7]

An observational study looked at outcomes of 2859 women who took an antidepressant during the 2 years prior to pregnancy. Compared to women who did not take an antidepressant during pregnancy, mothers who took an antidepressant during all 3 trimesters of pregnancy were 37% less likely to be breastfeeding upon hospital discharge. Mothers who took an antidepressant only during the third trimester were 75% less likely to be breastfeeding at discharge. Those who took an antidepressant only during the first and second trimesters did not have a reduced likelihood of breastfeeding at discharge.[31] The antidepressants used by the mothers were not specified.

A retrospective cohort study of hospital electronic medical records from 2001 to 2008 compared women who had been dispensed an antidepressant during late gestation (n = 575; venlafaxine n = 68) to those who had a psychiatric illness but did not receive an antidepressant (n = 1552) and mothers who did not have a psychiatric diagnosis (n = 30,535). Women who received an antidepressant were 37% less likely to be breastfeeding at discharge than women without a psychiatric diagnosis, but no less likely to be breastfeeding than untreated mothers with a psychiatric diagnosis.[32]

A woman with chronic depression was treated throughout pregnancy with extended-release venlafaxine 225 mg daily. She gave birth by cesarean section at 36.5 weeks and began to breastfeed her infant. The infant was not nursing adequately, but the mother pumped milk after each feeding and used it to supplement the infant. It was estimated that she was producing at least 900 mL of milk daily. By 8 days postpartum, she began to experience depression and aripiprazole 2 mg daily, which she had taken before pregnancy, was added to her regimen. After 3 days of combined therapy, she noticed a decrease in milk supply, and withing 21 days, lactation had ceased completely. Either aripiprazole or the combination with venlafaxine possibly caused a decrease in milk supply.[33]

A 22-year-old woman who had been taking slow-release venlafaxine 150 mg daily for 3 months reported bilateral breast engorgement and galactorrhea for 3 days after being prescribed cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily for 14 days 2 weeks prior. Laboratory and head CT results were normal except for a slight elevation in alkaline phosphatase and an elevated serum prolactin level. Her galactorrhea began decreasing within 2 weeks and disappeared in 3 weeks with no change in venlafaxine dosage. Her serum prolactin level also returned to normal. The authors felt that her symptoms and hyperprolactinemia were probably caused by cefpodoxime.[34]

In a study of 80,882 Norwegian mother-infant pairs from 1999 to 2008, new postpartum antidepressant use was reported by 392 women and 201 reported that they continued antidepressants from pregnancy. Compared with the unexposed comparison group, late pregnancy antidepressant use was associated with a 7% reduced likelihood of breastfeeding initiation, but with no effect on breastfeeding duration or exclusivity. Compared with the unexposed comparison group, new or restarted antidepressant use was associated with a 63% reduced likelihood of predominant, and a 51% reduced likelihood of any breastfeeding at 6 months, as well as a 2.6-fold increased risk of abrupt breastfeeding discontinuation. Specific antidepressants were not mentioned.[35]

Alternate Drugs to Consider

References

- 1.

- Larsen ER, Damkier P, Pedersen LH, et al. Use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2015;445:1-28. [PubMed: 26344706]

- 2.

- Uguz F. A new safety scoring system for the use of psychotropic drugs during lactation. Am J Ther 2021;28:e118-e26. [PubMed: 30601177]

- 3.

- Koren G, Moretti M, Kapur B. Can venlafaxine in breast milk attenuate the norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake neonatal withdrawal syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2006;28:299-301. [PubMed: 16776907]

- 4.

- Boucher N, Koren G, Beaulac-Baillargeon L. Maternal use of venlafaxine near term: Correlation between neonatal effects and plasma concentrations. Ther Drug Monit 2009;31:404-9. [PubMed: 19455083]

- 5.

- Weissman AM, Levy BT, Hartz AJ, et al. Pooled analysis of antidepressant levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1066-78. [PubMed: 15169695]

- 6.

- Ilett KF, Hackett LP, Dusci LJ, et al. Distribution and excretion of venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine in human milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998;45:459-62. [PMC free article: PMC1873542] [PubMed: 9643618]

- 7.

- Ilett KF, Kristensen JH, Hackett LP, et al. Distribution of venlafaxine and its O-desmethyl metabolite in human milk and their effects in breastfed infants. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002;53:17-22. [PMC free article: PMC1874551] [PubMed: 11849190]

- 8.

- Weissman AM, Wisner KL, Perel JM, et al. Venlafaxine levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants. Arch Womens Ment Health 2003;6 (Suppl 1):20. doi:10.1007/s00737-002-0163-1 [CrossRef]

- 9.

- Berle JØ, Steen VM, Aamo TO, et al. Breastfeeding during maternal antidepressant treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Infant exposure, clinical symptoms, and cytochrome P450 genotypes. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1228-34. [PubMed: 15367050]

- 10.

- Misri S, Corral M, Wardrop AA, et al. Quetiapine augmentation in lactation: A series of case reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:508-11. [PubMed: 16974194]

- 11.

- Newport DJ, Ritchie JC, Knight BT, et al. Venlafaxine in human breast milk and nursing infant plasma: Determination of exposure. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1304-10. [PubMed: 19607765]

- 12.

- Pogliani L, Baldelli S, Cattaneo D, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors passage into human milk of lactating women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019;32:3020-5. [PubMed: 29557689]

- 13.

- Schoretsanitis G, Augustin M, Sassmannshausen H, et al. Antidepressants in breast milk; Comparative analysis of excretion ratios. Arch Womens Ment Health 2019;22:383-90. [PubMed: 30116895]

- 14.

- Baldelli S, Pogliani L, Schneider L, et al. Passage of venlafaxine in human milk during 12 months of lactation: A case report. Ther Drug Monit 2022;44:707-8. [PubMed: 36101929]

- 15.

- Pan X, Rowland-Yeo K. Exposure of venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine in lactating mothers and their infants: Insights from a PBPK model. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2024;115:S105. doi:10.1002/cpt.3167 [CrossRef]

- 16.

- Hendrick V, Altshuler L, Wertheimer A, et al. Venlafaxine and breast-feeding. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:2089-90. [PubMed: 11729040]

- 17.

- 18.

- Hendrick V, Smith LM, Hwang S, et al. Weight gain in breastfed infants of mothers taking antidepressant medications. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:410-2. [PubMed: 12716242]

- 19.

- Pae CU, Kim JJ, Lee CU, et al. Very low dose quetiapine-induced galactorrhea in combination with venlafaxine. Hum Psychopharmacol 2004;19:433-4. [PubMed: 15303249]

- 20.

- Matthys A, Ambat MT, Pooh R, et al. Psychotropic medication use during pregnancy and lactation: Role of ultrasound assessment. Donald Sch J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;8:109-21. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10009-1345 [CrossRef]

- 21.

- Tran MM, Fancourt N, Ging JM, et al. Failure to thrive potentially secondary to maternal venlafaxine use. Australas Psychiatry 2016;24:98-9. [PubMed: 26850953]

- 22.

- Bhatia SC, Bhatia SK, Bencomo L. Effective treatment of venlafaxine-induced noncyclical mastalgia with bromocriptine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:590-1. [PubMed: 11001253]

- 23.

- Sternbach H. Venlafaxine-induced galactorrhea. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23:109-10. [PubMed: 12544389]

- 24.

- Ashton AK, Longdon MC. Hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea induced by serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibiting antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1121-2. [PubMed: 17606668]

- 25.

- Wichman CL, Cunningham JL. A case of venlafaxine-induced galactorrhea? J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:580-1. [PubMed: 18794664]

- 26.

- Karakurt F, Kargili A, Uz B, et al. Venlafaxine-induced gynecomastia in a young patient: A case report. Clin Neuropharmacol 2009;32:51-2. [PubMed: 18978497]

- 27.

- Berilgen MS. Late-onset galactorrhea and menometrorrhagia with venlafaxine use in a migraine patient. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;30:753-4. [PubMed: 21057247]

- 28.

- Suthar N, Pareek V, Nebhinani N, et al. Galactorrhea with antidepressants: A case series. Indian J Psychiatry 2018;60:145-6. [PMC free article: PMC5914246] [PubMed: 29736080]

- 29.

- Kameg BN, Wilson R. Venlafaxine-related galactorrhea in an adolescent female: A case report. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2022;40:106-8. [PubMed: 36064232]

- 30.

- Warren MB. Venlafaxine-associated euprolactinemic galactorrhea and hypersexuality: A case report and review of the literature. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36:399-400. [PubMed: 27219091]

- 31.

- Venkatesh KK, Castro VM, Perlis RH, et al. Impact of antidepressant treatment during pregnancy on obstetric outcomes among women previously treated for depression: An observational cohort study. J Perinatol 2017;37:1003-9. [PMC free article: PMC10034861] [PubMed: 28682318]

- 32.

- Leggett C, Costi L, Morrison JL, et al. Antidepressant use in late gestation and breastfeeding rates at discharge from hospital. J Hum Lact 2017;33:701-9. [PubMed: 28984528]

- 33.

- Walker T, Coursey C, Duffus ALJ. Low dose of Abilify (aripiprazole) in combination with Effexor XR (venlafaxine HCl) resulted in cessation of lactation. Clin Lact (Amarillo) 2019;10:56-9. doi:10.1891/2158-0782.10.2.56 [CrossRef]

- 34.

- Das N, Chadda RK. Hyperprolactinemic galactorrhea associated with cefpodoxime in a patient with recurrent depressive disorder on venlafaxine monotherapy: A case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2020;40:635-6. [PubMed: 33065718]

- 35.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Saha MR, Nordeng H, et al. Perinatal antidepressant use and breastfeeding outcomes: Findings from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2022;101:344-54. [PMC free article: PMC9564556] [PubMed: 35170756]

Substance Identification

Substance Name

Venlafaxine

CAS Registry Number

93413-69-5

Drug Class

Breast Feeding

Lactation

Milk, Human

Antidepressive Agents

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Disclaimer: Information presented in this database is not meant as a substitute for professional judgment. You should consult your healthcare provider for breastfeeding advice related to your particular situation. The U.S. government does not warrant or assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information on this Site.

- User and Medical Advice Disclaimer

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Record Format

- LactMed - Database Creation and Peer Review Process

- Fact Sheet. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed)

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - Glossary

- LactMed Selected References

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) - About Dietary Supplements

- Breastfeeding Links

- PMCPubMed Central citations

- PubChem SubstanceRelated PubChem Substances

- PubMedLinks to PubMed

- Review Desvenlafaxine.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Desvenlafaxine.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Citalopram.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Citalopram.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Distribution of venlafaxine and its O-desmethyl metabolite in human milk and their effects in breastfed infants.[Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002]Distribution of venlafaxine and its O-desmethyl metabolite in human milk and their effects in breastfed infants.Ilett KF, Kristensen JH, Hackett LP, Paech M, Kohan R, Rampono J. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002 Jan; 53(1):17-22.

- Review Marine Oils.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Marine Oils.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Review Bupropion.[Drugs and Lactation Database (...]Review Bupropion.. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

- Venlafaxine - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)Venlafaxine - Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®)

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

See more...